Introduction

Crohn’s disease is a chronic, relapsing inflammatory condition of the gastrointestinal tract, characterized by patchy, transmural inflammation that can affect any segment from mouth to anus. The aetiology remains multifactorial, involving genetic predisposition, immune dysregulation, and environmental triggers [1].

Imaging has become central to the management of inflammatory bowel disease, especially Crohn’s disease, as the field moves from symptom‑based assessment to objective treat‑to‑target strategies. This evolution is driven by the need for accurate diagnosis, comprehensive disease mapping, and precise monitoring of both inflammatory activity and complications. While endoscopy remains the reference standard for mucosal assessment, it is invasive and limited to the luminal surface. Cross‑sectional imaging modalities—primarily magnetic resonance enterography (MRE) and intestinal ultrasound (IUS)—have emerged as first‑line, non‑invasive tools [1, 2]. These techniques allow full‑thickness and extramural evaluation, essential for detecting active disease and complications such as strictures, fistulas, or abscesses.

2025 ECCO‑ESGAR‑ESP‑IBUS Guidelines

The latest ECCO‑ESGAR‑ESP‑IBUS guidelines recommend cross‑sectional imaging for both initial diagnosis and follow‑up of Crohn’s disease [2, 3]. IUS and MRE are first‑line modalities; CT should be reserved for acute settings due to radiation exposure. At first diagnosis, MRE is preferred over IUS for its accuracy in assessing disease extent, especially in the small bowel. Performing a complementary IUS may nevertheless be advantageous, since this baseline examination can serve as a reference point for follow‑up assessments. Both IUS and MRE are validated for evaluating treatment response and proactive monitoring of patients in clinical remission [2].

Imaging Features of Active Disease

On MRE, active Crohn’s disease is characterized by (1) bowel wall thickening (> 3 mm in distended loops), (2) high mural T2 signal intensity indicating oedema, (3) increased vascularization reflected by mural hyperenhancement and engorged vasa recta (“comb sign”), (4) ulcerations visible as small mural defects, and (5) perimural inflammation seen as high T2 signal intensity in the mesenteric fat (Figure 1). On IUS, the key features include (1) bowel wall thickening (>3 mm), (2) loss of mural stratification due to oedema, (3) increased (extra)mural vascularity on colour Doppler, (4) ulcerations, and (5) hyperechoic mesenteric fat and/or free fluid adjacent to the inflamed bowel segment (Figure 2) [1, 4].

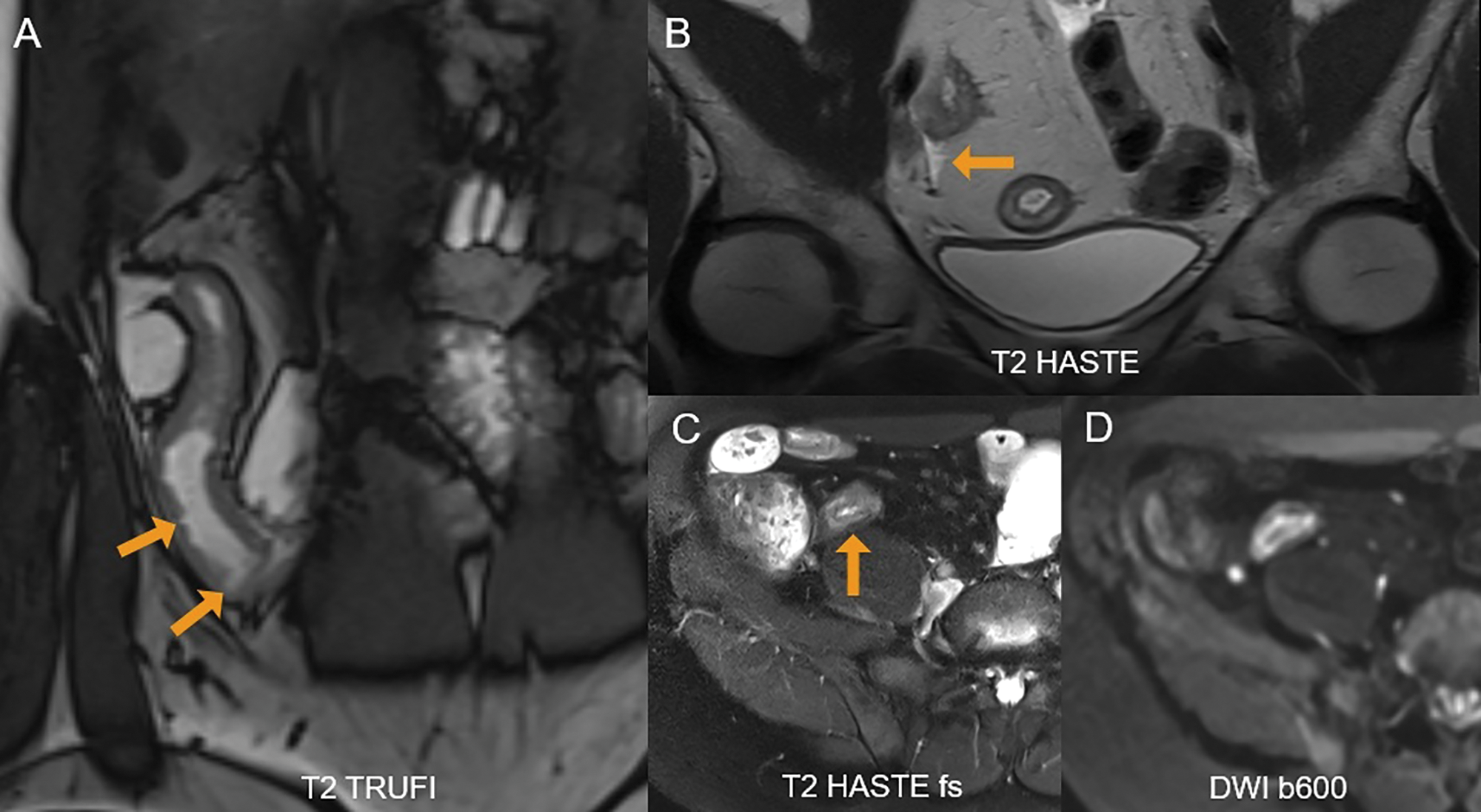

Figure 1

A 36‑year‑old female with active Crohn’s disease. (A) Coronal T2 TRUFI image shows ulcerations in the inflamed terminal ileum as focal intraluminal surface defects (arrows). (B) Perimural inflammation with adjacent free fluid is seen (arrow). (C) Fat‑suppressed T2‑sequence demonstrates high mural T2‑signal in the terminal ileum (arrow). (D) The inflamed segment also shows restricted diffusion.

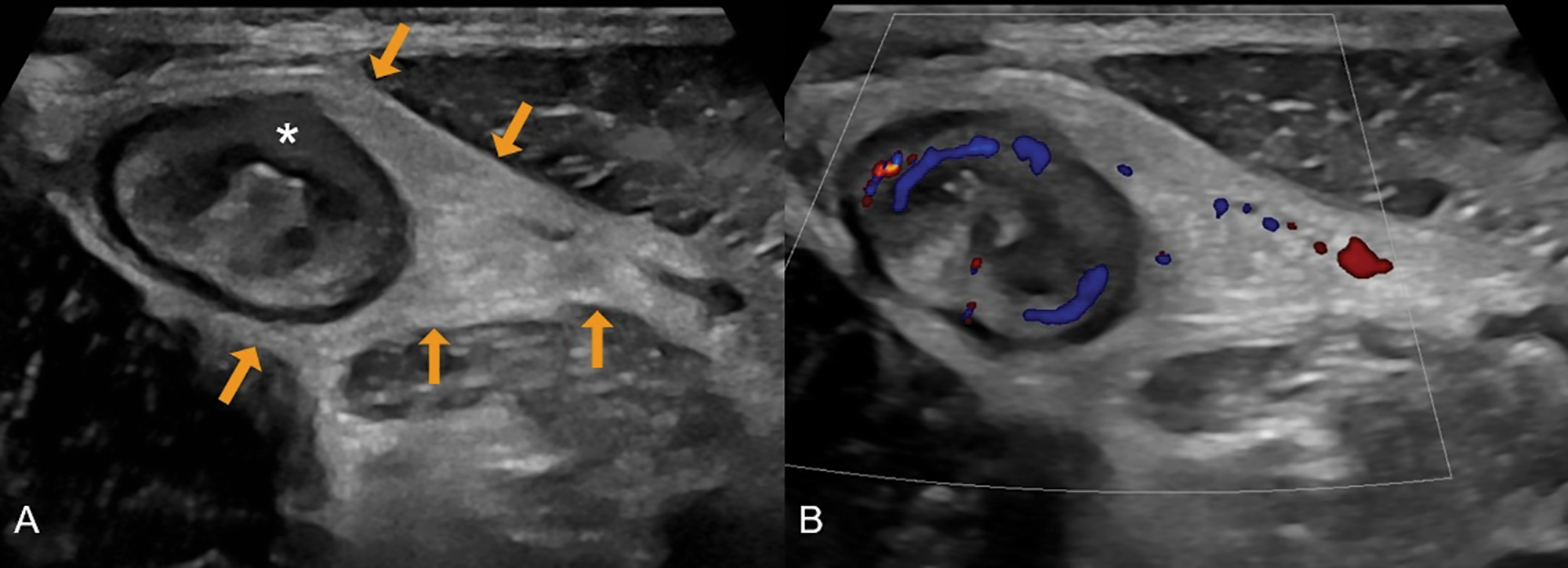

Figure 2

A 31‑year‑old male with newly diagnosed Crohn’s disease. (A) Greyscale ultrasound shows a thickened terminal ileum with extensive loss of mural stratification (asterisk) and hyperechoic fat wrapping (arrows). (B) Colour Doppler demonstrates increased vascularity in the ileal wall and adjacent inflamed fat.

Technical Considerations

MRE protocols should, at a minimum, include T2‑weighted sequences with and without fat suppression, as well as steady‑state free precession gradient‑echo sequences without fat suppression. In addition, at least two of the following optional sequences are recommended: pre‑ and post‑contrast T1‑weighted sequences, diffusion‑weighted imaging, and/or cine sequences for motility assessment. Oral fluid/contrast is essential to ensure adequate luminal distension (e.g., ingestion of 1 L of mannitol‑based or PEG solution 45 minutes before the examination). For ultrasound, an initial overview scan should be performed using a convex probe (3.5–5 MHz), followed by a high‑frequency linear probe (6–11 MHz) for detailed bowel wall assessment. Vascularity should be evaluated with colour Doppler imaging with appropriate settings. Oral contrast agents are not routinely used [1, 3].

Innovation & Future Perspectives

Recent advances in the field focus on functional and quantitative imaging. Cine MRI enables quantification of bowel motility, providing a functional biomarker for inflammation and treatment response [3, 4]. In daily clinical practice, motility sequences are also highly valuable for the early detection of small bowel strictures, as prestenotic dilatation may remain undetected on conventional static MRE images (Figure 3). Texture analysis and radiomics are being investigated for their potential in fibrosis quantification and outcome prediction. In parallel, artificial intelligence may enhance image interpretation, reduce interobserver variability, and support clinical decision‑making [5]. Finally, molecular imaging, including PET‑CT/PET‑MRI and novel tracers, offers the prospect of non‑invasive, quantitative assessment of intestinal inflammation and fibrosis at the molecular level [6].

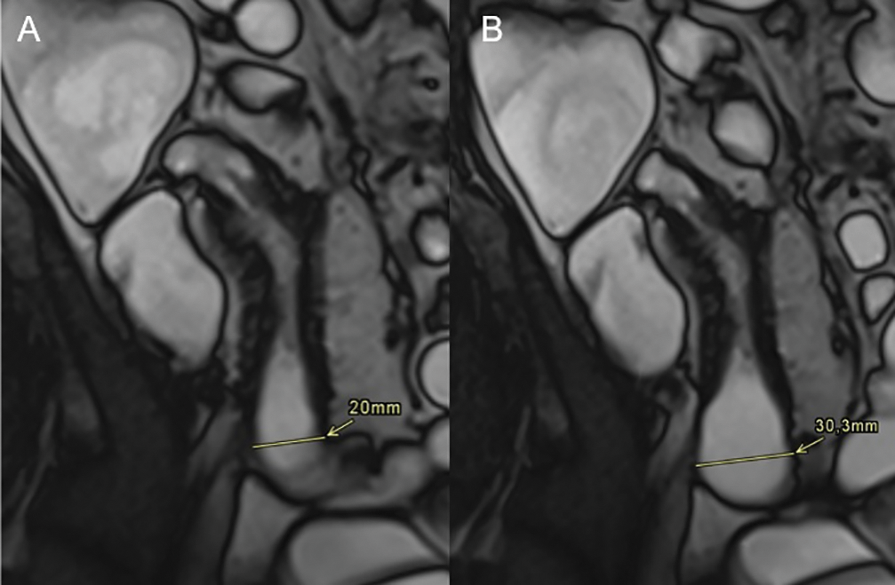

Figure 3

A 44‑year‑old male with Crohn’s disease in the terminal ileum. (A) Coronal T2 TRUFI image shows prestenotic dilatation of 20 mm, below the threshold for a definite stricture (≥30 mm). (B) A single frame from a CINE sequence demonstrates maximal distension of 30 mm, confirming stricturing Crohn’s disease.

Conclusion

The role of imaging in Crohn’s disease has expanded from mere diagnosis to central involvement in treatment strategies. IUS and MRE are the complementary cornerstones of imaging in inflammatory bowel disease, enabling accurate diagnosis, disease monitoring, and treatment response assessment. Technical refinements and innovations, such as motility MRI, are moving the field towards a more functional, patient‑tailored approach, strengthening cross‑sectional imaging as an indispensable pillar in the multidisciplinary management of inflammatory bowel disease.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.