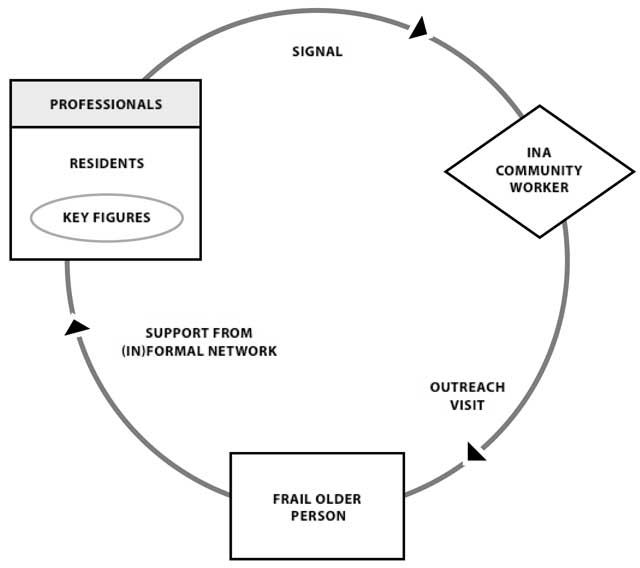

Figure 1

Working method INA.

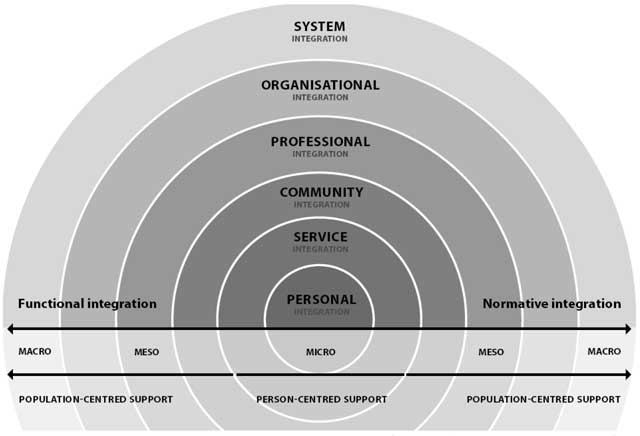

Figure 2

Integrated care model van Dijk, Cramm and Nieboer (adapted from Valentijn et al., 2013).

Table 1

Study participants.

| Participant | Gender | Background |

|---|---|---|

| Community workers | ||

| Participant 1 | woman | Community nurse INA with a social care background (specialized in coordinating voluntary work) |

| Participant 2 | woman | Community nurse INA with a health care background (specialized as a nurse practitioner) |

| Participant 3 | man | Community nurse INA with a social care background (specialized in community work) |

| Participant 4 | woman | Community nurse INA with a social care background (specialized in community work) |

| Managers/directors | ||

| Participant 5 | man | Manager health care organization |

| Participant 6 | man | Manager social care organization |

| Participant 7 | woman | Manager health care organization |

| Participant 8 | woman | Director health care organization |

| Municipal officers | ||

| Participant 9 | woman | Alderman (with a portfolio responsibility on participation and integration) |

| Participant 10 | woman | Alderman sub-municipality (with a portfolio responsibility on health and social care) |

| Participant 11 | man | Senior policy officer Social Support Act |

| Participant 12 | man | Program manager assisted living |

| Participant 13 | woman | Policy officer sub-municipality health and social care |

| Participant 14 | woman | Policy officer sub-municipality health and social care |

| Participant 15 | man | Policy officer health and social care |

| Older people | ||

| Participant 16 | woman | Older person who received INA support and resided in Oude Westen |

| Participant 17 | woman | Older person who received INA support and resided in Lombardijen |

| Participant 18 | woman | Older person who received INA support and resided in Kralingen |

| Other | ||

| Participant 19 | man | Project manager of INA |

| Participant 20 | man | Director procurement and policy of a health insurance company |

| Participant 21 | woman | Former politician who remained actively engaged in the field of long-term care (e.g. through her participation as a program member of the National Care for the Elderly Program) |

Table 2

Overview of our study findings.

| Integration level | Challenge | Key observations |

|---|---|---|

| Micro-level | ||

| Personal integration | Gaining trust | Obtaining older people’s trust was identified as a key prerequisite for the provision of person-centered support. Continuity, in turn, is a precondition for gaining trust. |

| Personal integration | Acknowledging and strengthening older people’s capabilities | The INA uses individualized support plans based on assessments of older people’s physical and social needs and capabilities. |

| Personal integration | Overcoming resistance to informal support | Community workers reported that older people had difficulty relying on informal networks; they were reluctant to ask for help and strongly desired independence. |

| Service integration | Engaging community resources | Community workers tried to mobilize volunteers to set up services, which was not always successful. |

| Service integration | Community workers must set up and track responses to interventions | To ensure service integration, community resources must be integrated throughout the process of signaling and supporting older people. Moreover, integrated care and support provision requires community workers to operate simultaneously at multiple levels. |

| Meso-level | ||

| Community integration | Building community awareness and trust | Community workers noted that conveying the INA’s message took time and that community members often hesitated to alert them to frail older persons, reluctant to interfere in someone’s life. |

| Community integration | Familiarity with the neighborhood | INA community workers must take the preferences, and sometimes prejudices, of support-givers and those in need of support into account. |

| Community integration | Adaption to new roles | The need for community integration requires professionals to reinvent their roles and serve as community workers. |

| Community integration | Sustaining relationships | To overcome barriers to community integration, community workers perceived that sustaining relationships was crucial in gaining access to frail older people and adequately assessing potential support-givers. |

| Professional integration | Individual skills | Recruitment of ‘entrepreneurial’ professionals with generalist and specialist skills to form diverse teams was crucial for professional integration. |

| Professional integration | Team skills | Discontinuity and a lack of mutual goals were found to hamper professional integration. |

| Organizational integration | Conflicting organizational interests | Although health and social care organizations recognize the need to collaborate, professionals feel that cost containments are forcing the prioritization of organizations’ interests over the common good. |

| Organizational integration | Lack of organizational commitment | Organizational integration was impeded by conflicting organizational interests and achieved only under favorable conditions, i.e. through a few willing professionals or managers and through high levels of trust built during previous collaborations. Structural incentives, such as the creation of opportunities for professionals to meet and gain insight in each other’s added value, facilitate organizational integration. |

| Macro-level | ||

| System integration | Inadequate financial incentives | Participants identified divergent flows of funds as the main cause for the lack of adequate financial incentives, affecting health and social care organizations and municipalities. |

| System integration | Inadequate accountability incentives | Health and social care organizations urged the municipality to reconsider its accountability incentives, annoyed by the focus on how they do things. |

| System integration | Inadequate regulatory incentives | Community workers are told that the provision of high-quality support requires innovation and collaboration among community partners while being required to bureaucratically account for all actions and meet targets. |

| Functional integration throughout all levels | The risk of excessive professional autonomy | Professional autonomy provided by project management was at odds with guidance in adopting a new professional role that matched the INA’s core principles. |

| Lack of support tools | The INA’s innovative character increased community workers’ need for guidance and supportive tools. The lack of material (i.e. decision-support tools or guidelines) and immaterial (i.e. acknowledgement) resources hampered the creation of shared values and aligned professional standards. | |

| High touch, low tech | In exchanging information, community workers often applied a ‘high touch, low tech’ approach. Rather than using the web-based portal developed for the INA, community workers preferred to consult each other by telephone or in person. | |

| Normative integration throughout all levels | Insecurity and mistrust | For older people, tender practices and policy changes often implied the rationing of publicly funded health and social care services and discontinuity in service delivery. Municipalities were similarly affected by a high degree of insecurity. |