1 Introduction

Academic literature widely recognises that biodiversity is essential for human existence. Biodiversity ensures the provision of critical ecosystem services, such as crop pollination (Kleijn et al. 2015) and cleaning air and absorbing carbon dioxide (Merk et al. 2023). The value of biodiversity is also increasingly acknowledged for overall good quality of life and happiness (Methorst et al. 2021; Reese et al. 2022). Despite this recognition, biodiversity loss remains a major societal challenge. Worldwide, 25% of all plants and animals are threatened and approximately one million are already extinct, many of which within the last few centuries as a result of human activities (Diaz et al. 2015; IPBES 2019). The accelerated rate of biodiversity loss has been referred to as the sixth mass extinction (Ceballos et al. 2015). Reduced biodiversity has been further linked to the spread of invasive species and pandemics (Vora et al. 2022; IPBES 2023). Overall, for decades, researchers have urged to stop environmental destruction and take action to counteract biodiversity loss (Ripple et al. 2017). Despite this extensive knowledge about the consequences of biodiversity loss, there is a lack of necessary societal changes to prioritise biodiversity, not least because biodiversity falls into the category of global or planetary commons (Mrema 2017; Rockström et al. 2024). To induce the necessary societal transformation, where biodiversity receives adequate priority, it is a prerequisite to understand underlying individual perspectives and values as well as the shifts of priorities in the context of broader societal and structural processes. A nuanced understanding of the dynamics in the formation of individual priorities is key to enabling attention and just responses to biodiversity loss, especially given the uncertainty surrounding tipping points of collapse in large shared social-environmental systems (Pascual et al. 2022).

This paper addresses how individuals prioritise tackling biodiversity loss in light of multiple other societal challenges. This is important because, in addition to biodiversity loss, people increasingly contend with information on a multitude of societal challenges and other issues that require attention and action. Other pressing challenges include climate change (e.g., heat waves, floods), economic downturns (e.g., inflation), pandemics (e.g., Covid-19), wars (e.g., war in Ukraine1), and the rise of autocratic leadership (Janssen 2022). However, it is an open question how one’s appreciation of biodiversity, as a prerequisite to support (political) action, is affected by thinking about other societal challenges. Various theoretical approaches come to distinct behavioural predictions in this regard.

A group of theories would predict information about multiple crises will lead to less attention to biodiversity. One strand of literature argues that since individuals are boundedly rational, their attention is limited (Simon 1957; Loewenstein and Wojtowicz 2023). For example, Evensen et al. (2021) and Sisco et al. (2023) have shown that there are finite pools of attention and worry – people become tired of constantly facing negative information, leading to a so-called saturation. Another strand of literature addressing information avoidance (Golman et al. 2017; Sunstein 2020) predicts that people tend to avoid information if it evokes depressing thoughts (e.g., feeling sad or anxious) even if the same piece of information has a positive instrumental value to make better decisions. Overall, finite pools of attention and worry, as well as avoiding undesirable information, may result in a lower appreciation of biodiversity in light of multiple crises.

Another group of theories would predict that the prospect of the expected harm and the accompanying worry about it will lead to more attention to biodiversity. People weigh losses psychologically more heavily than equivalent gains (i.e. loss aversion), which is a key feature of prospect theory, the leading descriptive theory for decision-making under uncertainty (Kahneman and Tversky 1979). This is also supported by experimental evidence that risk framing remains more effective than other simple frames such as co-benefits of action (Bernauer and McGrath 2016). In other words, people could be particularly attentive to negative information during multiple crises, which could also mean that information about biodiversity loss and its consequences together with information about other crises could accordingly improve how people prioritise biodiversity.

A different group of theories would predict that information about multiple crises will result in no important change in attention to biodiversity. Discursive-institutional theories such as institutional change and path dependence (North 1990; Williamson 2000) explain that change in dominant public discourse is often very slow and costly. In this sense, even fundamental societal transformations can be seen from the perspective of multiple incremental and micro processes of social change (Soliev et al. 2025). Some challenges have historically received much more public attention than biodiversity loss. For example, issues such as climate change and natural disasters (e.g., extreme weather events, drought, floods, heatwaves; McDonald et al. 2015; Peisker 2023) have frequently been reported in the media and continue to compete for their own public attention over several decades. In addition, salience theory (Bordalo et al. 2022) would support that the attention of individuals will stay with those crises which they can easily recognise and relate to. The fact that biodiversity loss arguably has developed fewer salient features so far would therefore add to the difficulty of attracting attention to its importance and urgency. Since attention is directed to a limited fraction of challenges, people’s appreciation of biodiversity may be unaffected even when information about it is made more prominent.

In light of these differing perspectives, we explore how reminding individuals of other societal challenges – specifically the Covid-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine – influences the priority given to tackling biodiversity loss. Both societal challenges are important to study because they have brought substantial changes to people’s lives, arguably significantly affecting the priorities people give to various societal issues. This is particularly well-evidenced in terms of individuals’ worries about rising costs of living, and accordingly, preferences on where government spending and support should be directed. According to a representative survey in 2022, when these two challenges particularly dominated the societal discourse and media, the Germans’ five biggest fears were related to rising food costs, housing affordability, and tax increases/benefit cuts by Covid-19 (Destatis Online 2022).

We are also interested in whether communicating a causal link between biodiversity loss2 and Covid-19 as well as the war in Ukraine matters. There is growing scientific evidence that a nexus exists between biodiversity loss and emerging infectious diseases such as Covid-19 (IPBES 2020; Tollefson 2020). In this sense, biodiversity loss, caused by land-use change, intensive livestock production, wildlife trade, and climate change, is one important anthropogenic driver that promotes zoonotic pathogen spillover and disease emergence (Lawler et al. 2021). At the same time, the war in Ukraine caused widespread damage to ecosystems, including forests, wetlands, and agricultural land by the destruction of large areas of natural habitats and increasing stress on other locations of agricultural food production for compensating the deficits caused by the war and disruptions of the supply chains (OECD 2020; Chowdhury et al. 2023).

Experimental evidence is particularly valuable for analysing multiple crises. Many variables vary at the same time and third variables often prevent drawing causal inference. To overcome these challenges, we conduct a randomised, controlled information provision experiment (Haaland et al. 2023). All experimental participants were exposed to a compact piece of information about biodiversity loss taken from the media. In the treatment conditions, they were given additional information about Covid-19 or the war in Ukraine, respectively. The war and the pandemic were communicated to the experimental participants either as an independent crisis (i.e. without referring to a causal relationship to biodiversity) or as a crisis with some causal link to biodiversity. After assigning participants to scenarios, we elicited their priority to biodiversity loss. To this end, participants were given a total of 100 virtual points and asked to allocate them to different societal challenges (including, most notably, counteracting biodiversity loss) corresponding to the relative importance they assign to these challenges. We use the number of points allocated to biodiversity as our variable of interest. Our procedure overcomes several shortcomings of conventional willingness to pay (WTP) analysis (Sunstein 2020). Most notably, allocating a fixed number of virtual points instead of stating a freely chosen amount of money allows for revealing the extent to which biodiversity is important to people, irrespective of their income. Moreover, we circumvent the disparity between willingness to pay and willingness to accept (Plott and Zeiler 2005; Vossler et al. 2023).

Furthermore, we conducted a follow-up study to better understand individuals’ perceptions of societal challenges – especially in terms of how their experiences might be shaping their worldviews more fundamentally based on the institutional change theory that predicts historical developments to be the main source shaping worldviews (North 1990; Williamson 2000). In a survey, we explored how multiple challenges might have affected individuals’ perceptions or even personality, particularly as there have been reports of rather substantial effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on behaviour and perception of individuals (Giuliano and Spilimbergo 2025). Standard economics assumes that personality traits (e.g., risk preferences, time preferences) are stable over time (Stigler and Becker 1977). However, social scientists are increasingly challenging this assumption. For example, there is evidence that natural disasters can lead to various outcomes: increased risk-taking (Islam et al. 2020), increased risk-aversion (Avdeenko and Eryilmaz 2021), or no stable effect on an individual’s risk preferences (Thamarapani and Rockmore 2022). Likewise, it is possible that experiencing multiple crises can influence preferences and behaviours (Giuliano and Spilimbergo 2025), which in turn can be relevant to the appreciation of biodiversity.

In this paper, we show that participants of the experiment prioritise biodiversity less after being reminded of other crises (Covid-19 and the war in Ukraine, note that the experiment was conducted in 2022, at a time when both of these challenges were particularly salient). However, we also find that this effect is relatively small in magnitude. Moreover, communicating a link between biodiversity and other crises does not seem to alter our findings. In contrast, personal importance of biodiversity to individuals appears to be a much stronger predictor than information provision in explaining the priority to biodiversity in our experiment. Finally, our follow-up survey indicates that the accumulation of negative news information may, in fact, lead to a stronger avoidance of information by individuals (i.e. resulting in less attention to biodiversity loss).

The added value of this paper to the existing knowledge is threefold. First, it contributes to a better understanding of the role of biodiversity in times of multiple crises. In this context, it provides insights into individuals’ willingness to contribute to addressing biodiversity loss in terms of provision dilemmas that are particularly prominent in sustaining common pools resources (Ostrom 1990) and global public goods (Buchholz and Sandler 2021). Most current studies focus on one single crisis, such as climate change (Carter et al. 2018; Aragón et al. 2021), Covid-19 (Chenarides et al. 2021; Douglas 2021), biodiversity loss (Oliver 2016; Johnson et al. 2017), and the war in Ukraine (Pereira et al. 2022; Rawtani et al. 2022). Studies investigating the role of biodiversity amidst multiple crises are notably less prevalent. Second, the paper brings forward the discussion of causal relationships by using an experimental design. Studying real data is often limited to explorations of correlations (Bryman 2016). Third, it adds value to the discussion of the behavioural consequences of reminders and choices that emphasise different elements in otherwise largely equivalent content. Reminders have been described as quite effective in the literature of nudging (Sunstein 2014; DellaVigna and Linos 2022). However, in our experiment, personal importance to biodiversity explains individual behaviour much better than reminders do. To put it differently, our paper provides evidence on the limitations of nudges. Fourth, we contribute to a better understanding of individuals’ reaction to negative information. Following the prevailing media coverage in Germany, we use negative framings (i.e. suffering from biodiversity losses instead of gains if biodiversity is protected). Kahneman and Tversky (1979), a prominent milestone in the framing literature, as well as many who followed them, showed that highlighting losses is an efficient way of communication. However, as our follow-up survey indicates, people are increasingly tired of negative information. It is possible that the current understanding of communication neglects the role of saturation. Therefore, interdisciplinary discussions seem necessary, such as the one by Louder and Wyborn (2020), on the relevance of positive narratives (i.e. up-beat inspiring rhetoric), as well as on situated or context-dependent analysis of factors determining whether information and its contents will achieve its desired goals (Soliev et al. 2025).

To investigate these differing theoretical explanations in more detail and to present our experimental methods and results, in the next section we continue with our study design and describe the sampling of the experimental participants. We then report our results and discuss them in terms how they advance our current understanding of biodiversity prioritisation in times of multiple societal challenges and how experimental approaches can advance our knowledge further. We conclude by providing avenues for future research.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Main experiment on biodiversity prioritisation

2.1.1 Study design

Variable of interest: priority given to addressing biodiversity loss

We presented experimental participants with a list of societal challenges, including the protection of species and biodiversity, climate protection, protection from Covid-19, public health, security and defence, integration of refugees, burden from increased prices, and education (Appendix I). Our items cover the categories of Marasco et al.’s (2023) pyramid of worries (from bottom to top: economy, personal safety, immigration, social issues, and environment). Experimental participants were asked to express their priority in addressing these challenges. For this purpose, they were given a total of 100 virtual points. The participants’ task was to allocate any integer values of these points to the various societal challenges to express their respective level of appreciation. The amount people allocate to biodiversity is referred to as priority to biodiversity throughout this paper. The sequence of societal challenges was randomised to mitigate possible order effects.

Scenarios

Before measuring priority to biodiversity, experimental participants were randomly assigned to one of five scenarios containing news items about societal challenges (see Table 1 for an overview and Appendix II for the wording used in the experiment). In the baseline scenario (scenario 1), experimental participants were reminded of biodiversity loss. In all other scenarios, experimental participants were also prompted to recall additional societal challenges. Scenarios 2 and 3 included reminders of Covid-19, with scenario 3 establishing a causal link between the two societal challenges. Scenarios 4 and 5 included reminders of the war in Ukraine, with scenario 5 establishing a causal link between the two societal challenges. To ensure a high level of ecological validity, we used news stories from the media in Germany.

Explanatory variables

In addition to priority to biodiversity and the various scenarios described above, we elicited several other constructs. As explained below, we measured risk preferences, time preferences, need for closure, locus of control, Big Five, sociodemographic variables, and some additional variables related to biodiversity. Risk and time preferences are important to consider because numerous events entail uncertainty and substantial future implications (Barseghyan et al. 2018). Need for closure, an individual’s tendency to avoid ambiguity, is rarely used in economic studies (Gruener and Mußhoff 2023), which is surprising because people tend to seek easy answers to complex phenomena, especially during times of multiple societal challenges. Locus of control links the success or failure to one’s own action (internal locus of control) or external circumstances (external locus of control) (Rotter 1966). In the realm of behavioural economics in general and biodiversity in particular, the action of people to protect something, for example biodiversity, may be limited if they think that their actions does not influence outcomes. Furthermore, the Big Five dimensions (neuroticism, agreeableness, extraversion, openness, and conscientiousness) are included since they are frequently used in the social sciences, including studies on environmental preferences (Soliño and Farizo 2014; Eck and Gebauer 2022). We also collected several sociodemographic variables (gender, education, age, political attitude, income, population density in residential area) and asked the participants to indicate how personally important biodiversity was to them.

2.1.2 Recruitment and description of the sample

Recruitment

Using the services of a professional survey company (Bilendi), a total of 1,000 individuals were recruited online between June 22 and June 30, 2022. The target population was a quota-representative sample of the population in Germany by age, gender, and education. Ethical approval (IRB) was obtained from Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg before data collection.

Description of experimental participants

The sample comprised an equal number of male and female individuals, with an average age of 44.70 (sd = 14.34) years and about one-third with a university-entry degree. Thus, the sample was roughly quota-representative of the German population in terms of gender, age, and education (Statista 2022a, 2022b). Further details can be found in Appendix III.

Randomisation check

Participants were randomly assigned to one of the respective scenarios. Randomisation balances known and unknown confounders in expectation (Dunning 2012). Since study findings are susceptible to bias if there are differences in the characteristics of the participants across the various scenarios, known confounders are often controlled for in regression analysis (Cohn et al. 2015). We tested for equality in the distribution of potential determinants of our variable of interest (priority to biodiversity) across all scenarios using the Kruskal-Wallis test (a generalization of the two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum test) for ordinal variables and chi-square tests for binary variables, respectively (Appendix III). As all P-values are relatively large (all exceed 0.1), we conclude that randomisation worked well.

2.2 Follow-up survey on the perception of multiple crises

As an integral part of another online data collection, participants were explicitly asked about whether and how experiencing multiple challenges in fact might have affected them in more substantial ways too, that is their perceptions about themselves or even personality (i.e. perceived change of personality). This helps us to interpret the findings of our main experiment. Participants of the survey were presented with the following paragraph:

“Multiple crises – Do crises change our personality?

Currently, our daily lives are shaped by a multitude of crises. This includes the COVID-19 pandemic, which has led to significant changes in societal life (e.g., contact restrictions, lockdowns). Another crisis is the war in Ukraine. Even in Germany, the consequences are being felt: prices for food and energy are rising significantly. Furthermore, there are concerns about current global warming, with implications such as an increase in extreme weather events (e.g., heatwaves) and forest dieback.”

Participants were then asked on a 5-point Likert scale from No (=1) to Yes (=5) whether their experiences of these crises have changed them as a person and to provide reasons for their answer.

The study was conducted with a sample of 1,000 participants residing in Germany between July 19 and July 30, 2022. The half of the participants identified as male or female, average age of participants was 44.85 (sd = 14.52) years, and 54.4% had at least a university-entry degree.

3 Results

3.1 Priority to biodiversity

3.1.1 Overall priority to biodiversity

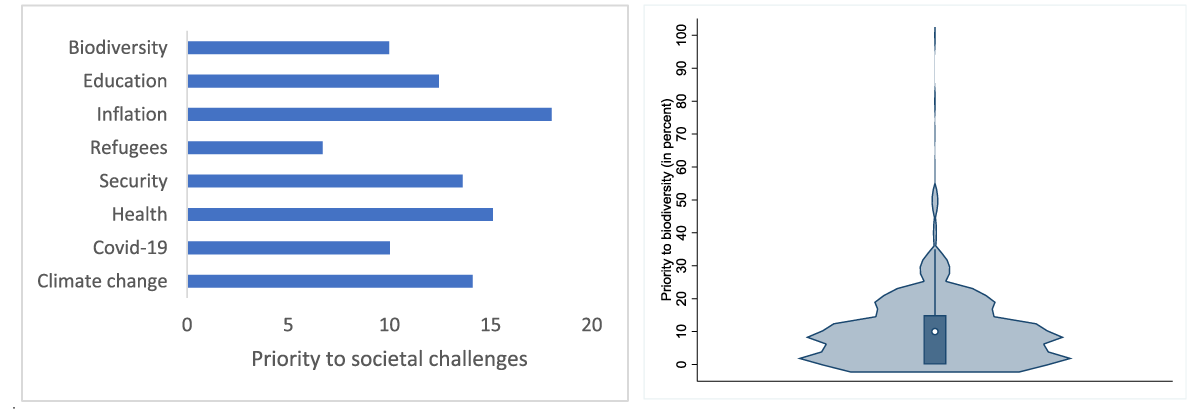

Overall, biodiversity received close to 10% of the total points, which is substantial given the other competing societal challenges, but still fairly low in comparison to other categories such as inflation, health, and climate change. Out of possible 100 points, on average, experimental participants allocated 9.98 points (sd = 10.90) to biodiversity. The median value is 10 points. Notably, 24% of participants allocated zero points to biodiversity. Figure 1 visualizes the average points across groups by the societal challenge and the distribution of the priority to biodiversity.

Figure 1

Average points across groups (a) and distribution in priority to biodiversity (b). Note: the violin plot shows the distribution of responses through a combination of a kernel density plot and a box plot.

3.1.2 Understanding biodiversity prioritisation

Overall effects of information provision are mixed

The initial investigation indicates that the effects of information provision on priority to biodiversity are mixed – notably, for both the overall sample and the sample without those who assigned zero points to biodiversity (Table 2). While adding another societal challenge seems to reduce priority to biodiversity, the effects of mentioning the causal links between challenges vary across the scenarios. Most importantly, the mean value of priority to biodiversity is highest in the baseline scenario (i.e. without information about other challenges). Then, what is the effect of communication of a causal relationship between biodiversity and other challenges? The average priority to biodiversity appears to be higher when biodiversity loss and Covid-19 are communicated without a causal relationship. Conversely, it seems that the communication of a causal link between biodiversity loss and war in Ukraine increases the priority to biodiversity.

Table 2

Influence of information on priority to biodiversity (a).

| SCENARIO | IOVERALL SAMPLE N = 1,000 | IISAMPLE WITHOUT ZEROS N = 726 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Biodiversity loss | 10.92 (15.17) | 15.94 (16.00) |

| 2 Biodiversity loss and Covid-19 | 9.76 (9.58) | 13.19 (8.87) |

| 3 Biodiversity loss and Covid-19 (containing causal link) | 9.02 (8.66) | 12.70 (7.66) |

| 4 Biodiversity loss and War in Ukraine | 9.61 (10.78) | 13.25 (10.58) |

| 5 Biodiversity loss and War in Ukraine (containing causal link) | 10.62 (9.00) | 13.79 (7.83) |

[i] (a) Mean values, standard deviations in brackets.

Personal importance of the issue is a stronger predictor than information provision

The results of the regression analysis show that an individual’s attitude towards biodiversity loss is more important than being reminded of crises and their links. Here, we should note that based on our initial exploration of the empirical data and the model-fitting process, we took a few steps that should be reported. To analyse the null hypothesis of no difference between the respective treatment conditions and the baseline scenario, regression analysis was employed. We decided for count data models to measure priority to biodiversity, as we used the number of points allocated to the societal challenge of biodiversity. Negative Binomial regressions were employed to account for overdispersion (i.e. variance exceeds the mean; in our case 9.98<<118.76), which is common with count data (Cameron and Trivedi 2022). Taking these considerations into account, the regressions presented in Table 3 explain priority to biodiversity using treatment conditions, personality traits and socio-demographics, and personal importance of biodiversity. The most comprehensive regression (panel III) is our main specification. It shows that all four treatment conditions are not statistically significant compared to the baseline condition (P-values > 0.1). In contrast, personal importance of biodiversity is highly statistically significant (P-value < 0.001) and has a substantial effect size. In addition to the main finding here that highlights the role of how individuals perceive personal importance of biodiversity, the findings of the control variables indicate associations between priority to biodiversity and both gender and income, which can or even should be analysed in future studies with new data.

Table 3

Negative binomial regressions to explain priority to biodiversity (for the overall sample).

| NEGATIVE BINOMIAL REGRESSIONS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | ||||

| COEF. (r.SE) | P | COEF. (r.SE) | P | COEF. (r.SE) | P | |

| Treatments | ||||||

| (2) Covid-19 | –0.112 (0.120) | 0.349 | –0.075 (0.114) | 0.514 | –0.051 (0.113) | 0.649 |

| (3) Covid-19 link | –0.191 (0.119) | 0.109 | –0.148 (0.115) | 0.196 | –0.040 (0.115) | 0.732 |

| (4) Ukraine | –0.128 (0.126) | 0.308 | –0.095 (0.120) | 0.426 | –0.009 (0.118) | 0.938 |

| (5) Ukraine link | –0.028 (0.115) | 0.805 | –0.007 (0.109) | 0.950 | 0.010 (0.109) | 0.931 |

| Risk seeking | –0.010 (0.015) | 0.496 | –0.001 (0.015) | 0.927 | ||

| Patience | 0.031 (0.015) | 0.044 | 0.020 (0.014) | 0.165 | ||

| Nfcs | –0.005 (0.004) | 0.180 | –0.007 (0.004) | 0.075 | ||

| Locus of control, internal | –0.017 (0.049) | 0.731 | –0.042 (0.047) | 0.378 | ||

| Locus of control, external | 0.094 (0.049) | 0.055 | 0.033 (0.050) | 0.512 | ||

| Extraversion | 0.032 (0.038) | 0.395 | 0.036 (0.038) | 0.343 | ||

| Agreeableness | –0.065 (0.043) | 0.132 | –0.017 (0.044) | 0.698 | ||

| Conscientiousness | 0.048 (0.043) | 0.263 | 0.069 (0.043) | 0.108 | ||

| Neuroticism | –0.002 (0.049) | 0.960 | 0.034 (0.045) | 0.455 | ||

| Openness | 0.083 (0.034) | 0.015 | 0.018 (0.035) | 0.618 | ||

| Gender | 0.120 (0.074) | 0.104 | 0.186 (0.072) | 0.010 | ||

| Education | 0.023 (0.026) | 0.381 | –0.013 (0.026) | 0.609 | ||

| Age | 0.005 (0.016) | 0.757 | –0.002 (0.016) | 0.905 | ||

| Age2 | –0.000 (0.000) | 0.789 | –0.000 (0.000) | 0.990 | ||

| Politics: right | –0.047 (0.020) | 0.021 | –0.034 (0.021) | 0.112 | ||

| Population density | 0.009 (0.017) | 0.590 | –0.0011 (0.017) | 0.492 | ||

| Income | 0.070 (0.026) | 0.007 | 0.065 (0.026) | 0.014 | ||

| Personal importance of biodiversity | 0.388 (0.035) | 0.000 | ||||

| N | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | |||

| Prob > chi2 | 0.3503 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0004 | 0.0046 | 0.0176 | |||

Further analysis confirms effects inside and outside the bubble

Robustness check using further analysis confirms that the personal importance of biodiversity remains the primary driver to explain biodiversity prioritisation, particularly in what we call inside and outside the biodiversity bubble. That is those who a priori consider biodiversity important and those who do not. Technically speaking, we should note that biodiversity prioritisation can be conceptualised as a two-stage decision problem: (i) whether or not to assign any points to the societal challenge of biodiversity, and (ii) how many points to assign if a positive decision is made. This distinction is interesting to examine, as in our experiment a considerable number of participants assign zero points to the societal challenge of biodiversity. These participants may be characterised as operating “outside the biodiversity bubble,” whereas participants deliberate over the number of points (and not if points should be assigned at all) can be seen as acting “inside the biodiversity bubble.” The decision problems may vary in the efficacy of information provision about societal challenges and the relevance of other behavioural drivers. To check the robustness of our previous findings and to analyse the two-stage decision problem, we employ a linear hurdle model, consisting of two separate regressions corresponding to each decision stage (Cameron and Trivedi 2022). The results of the regression analysis of our main specification (containing treatment conditions, personality traits and socio-demographics, and personal importance of biodiversity) are depicted in Table 4. In the selection model (stage I), the P-values for all treatments exceed 0.1, indicating no statistically significant effects at conventional levels. The strongest predictor of biodiversity prioritisation – both in terms of effect size and statistical significance – is the personal importance of biodiversity. In the outcome model (stage II), information provision on challenges is negatively associated with biodiversity prioritisation, and statistically significant at the 10% level (with the exception of treatment 4, which is above 0.1). While personal importance of biodiversity remains the primary driver, here too, the results from the control variables call for future research addressing patience, gender, political attitude, need for closure, locus of control (internal), and conscientiousness.

Table 4

Linear hurdle model to explain biodiversity prioritisation (N = 1,000).

| STAGE I: SELECTION MODEL | STAGE II: OUTCOME MODEL | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COEF. (SE) | P | COEF. (SE) | P | |

| Treatments | ||||

| (2) Covid-19 | 0.2145 (0.1419) | 0.131 | –5.2133 (2.7503) | 0.058 |

| (3) Covid-19 link | 0.0705 (0.1387) | 0.611 | –5.0220 (2.8168) | 0.075 |

| (4) Ukraine | 0.1249 (0.1413) | 0.377 | –4.0147 (2.7654) | 0.147 |

| (5) Ukraine link | 0.2284 (0.1430) | 0.110 | –4.6171 (–4.6171) | 0.085 |

| Risk seeking | –0.0216 (0.0196) | 0.273 | 0.2992 (0.3973) | 0.451 |

| Patience | 0.0327 (0.0188) | 0.082 | –0.0764 (0.3831) | 0.842 |

| Nfcs | –0.0034 (0.0050) | 0.496 | –0.2271 (0.0984) | 0.021 |

| Locus of control, internal | 0.0485 (0.0638) | 0.447 | –3.2953 (1.2737) | 0.010 |

| Locus of control, external | 0.0282 (0.0592) | 0.634 | 1.2255 (1.1625) | 0.292 |

| Extraversion | 0.0522 (0.0522) | 0.317 | –0.0253 (1.0401) | 0.981 |

| Agreeableness | –0.0162 (0.0576) | 0.778 | –0.6398 (1.106) | 0.563 |

| Conscientiousness | –0.0198 (0.0608) | 0.745 | 2.2784 (1.2015) | 0.058 |

| Neuroticism | 0.0162 (0.0587) | 0.782 | –0.0971 (1.1561) | 0.933 |

| Openness | 0.1081 (0.0519) | 0.037 | –1.1365 (1.0136) | 0.262 |

| Gender | 0.2306 (0.0981) | 0.019 | 1.2872 (1.9190) | 0.502 |

| Education | 0.0371 (0.0384) | 0.335 | –0.7903 (0.7233) | 0.275 |

| Age | –0.0287 (0.0226) | 0.204 | 0.4875 (0.4485) | 0.277 |

| Age2 | 0.0003 (0.0002) | 0.262 | –0.0051 (0.0049) | 0.296 |

| Politics: right | –0.0773 (0.0259) | 0.003 | 0.1648 (0.4798) | 0.731 |

| Population density | 0.0086 (0.0235) | 0.713 | –0.2391 (0.4607) | 0.604 |

| Income | 0.0903 (0.0358) | 0.012 | 0.9217 (0.7158) | 0.198 |

| Personal importance of biodiversity | 0.3170 (0.0446) | 0.000 | 7.9505 (1.1623) | 0.000 |

| Prob > chi2 | 0.0000 | |||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0344 | |||

3.2 Personal importance of biodiversity

The analysis shows that personal importance is positively associated with patience (i.e. time preferences), openness to experience, education and locus of control (both internal and external) (Table 5). A further prominent finding is that leaning towards right-wing parties is negatively associated with personal importance of biodiversity. We should remind, personal importance of biodiversity is measured on a 5-point scale, ranging from very unimportant (=1) to very important (=5). We used both simple OLS regressions and ordered logit regressions. In case of any difference, the latter is our preferred model (Long and Freese 2014).

Table 5

OLS and Ordered logit regressions to explain personal importance of biodiversity (N = 1,000).

| LINEAR REGRESSION | ORDERED LOGISTIC REGRESSION | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COEF. (R.SE) | BETA | P | ODDS RATIO (R.SE) | P | |

| Risk seeking | –0.019 (0.015) | –0.048 | 0.189 | 0.960 (0.026) | 0.127 |

| Patience | 0.054 (0.014) | 0.140 | 0.000 | 1.109 (0.028) | 0.000 |

| Nfcs | 0.004 (0.004) | 0.043 | 0.217 | 1.011 (0.007) | 0.103 |

| Locus of control, internal | 0.119 (0.049) | 0.096 | 0.015 | 1.274 (0.108) | 0.004 |

| Locus of control, external | 0.116 (0.044) | 0.099 | 0.009 | 1.252 (0.097) | 0.004 |

| Extraversion | 0.022 (0.042) | 0.020 | 0.593 | 1.021 (0.078) | 0.789 |

| Agreeableness | –0.071 (0.047) | –0.054 | 0.133 | 0.885 (0.076) | 0.154 |

| Conscientiousness | 0.013 (0.045) | 0.010 | 0.776 | 1.050 (0.088) | 0.563 |

| Neuroticism | –0.008 (0.044) | –0.008 | 0.850 | 0.966 (0.077) | 0.663 |

| Openness | 0.182 (0.039) | 0.159 | 0.000 | 1.422 (0.105) | 0.000 |

| Gender | –0.054 (0.069) | –0.026 | 0.429 | 0.921 (0.113) | 0.501 |

| Education | 0.072 (0.026) | 0.095 | 0.006 | 1.137 (0.055) | 0.008 |

| Age | 0.003 (0.016) | 0.036 | 0.869 | 1.003 (0.028) | 0.918 |

| Age2 | –0.000 (0.000) | –0.005 | 0.983 | 1.000 (0.000) | 0.999 |

| Politics: right | –0.069 (0.019) | –0.121 | 0.000 | 0.877 (0.034) | 0.001 |

| Population density | 0.030 (0.017) | 0.056 | 0.077 | 1.061 (0.033) | 0.056 |

| Income | 0.002 (0.026) | 0.003 | 0.939 | 0.990 (0.045) | 0.824 |

| Prob > F/Prob > chi2 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |||

| R2/Pseudo R2 | 0.0999 | 0.0407 | |||

3.3 Multiple challenges and personality

3.3.1 Perceived effects of multiple challenges on personality

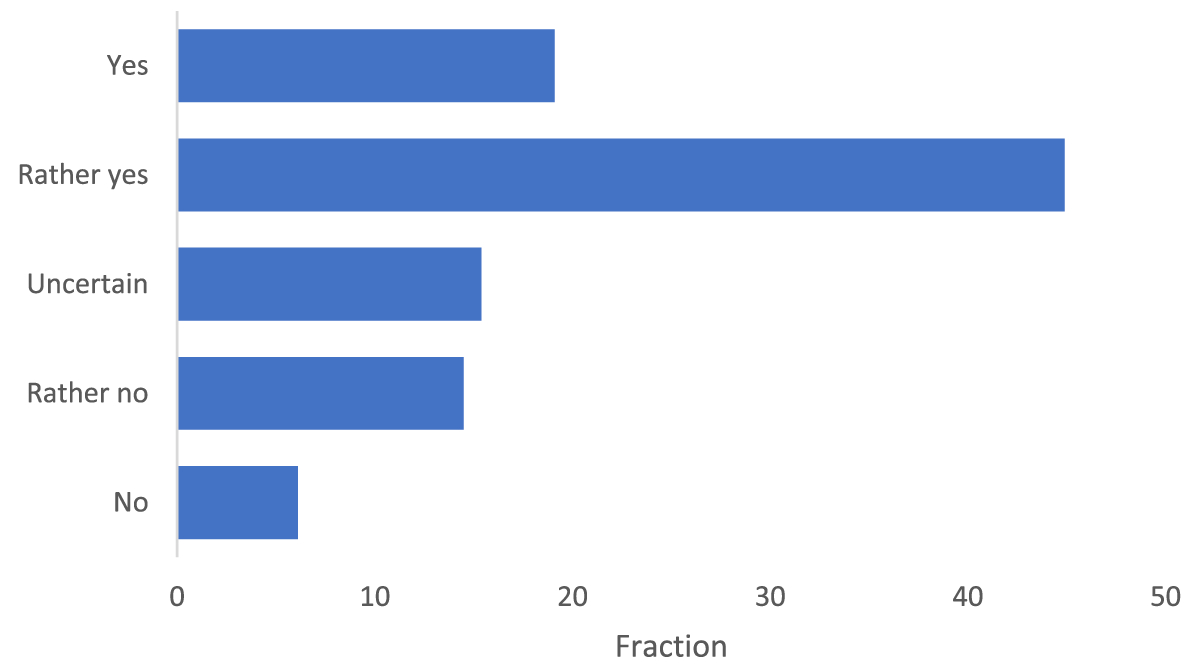

The majority of the participants (64.00%) indicated that experiencing multiple challenges either had changed or rather had changed them as a person (Figure 2). Only 20.60% of the respondents answered that the experience of multiple crises had not changed or rather had not changed them as a person. A total of 15.40% were uncertain.

Figure 2

Distribution of responses to the main question in study 2: Have your experiences of the multiple challenges changed you as a person?

Subsequently, participants who believed that multiple challenges had an impact on their personality (N=640) were asked to provide reasons. It should be noted that the number of responses can only be interpreted as a lower threshold, as it was collected using an open-ended question – that is some respondents might have underreported their perceptions. Based on the authors’ in-depth content analysis, the five most frequent categories can be roughly grouped as follows:

More conscious consumption/purchasing (due to factors, such as price increase, environmental concerns, health considerations) (22.34%)

Fear of the future/pessimism (14.84%)

Emotional response (e.g., feeling sad) (13.59%)

Stronger appreciation for pleasure: life is perceived more consciously – wealth and health recognised as valuable goods in the light of negative experiences (13.28%)

Being more cautious, less willingness to take risks (9.38%)

3.3.2 Negative narratives and saturation of attention

Regarding changes of personality as a consequence of multiple crises, some participants provided responses suggesting possible saturation of attention. We want to briefly report two particularly interesting and illustrative responses in this regard:

“The news makes me depressed. As a mother of a young child, I worry about what kind of world it will grow up in. I feel almost numb to the constant bad news. In order not to become sad any further, I almost avoid consuming news. However, I would still want to believe that we as a society can still somehow fix this.”

“You become numb and don’t want to deal with these issues or hear about them anymore.”

Both quotes touch upon the phenomenon of information avoidance (Sunstein 2020). It refers to the deliberate avoidance of freely available information, often to avoid anticipated negative information (Golman et al. 2017). Negative information, such as reports on increased prices can be useful – individuals might incorporate the information into their decision calculus. However, as expressed in the quotes, such information can be burdensome, leading individuals to prefer avoiding it. As discussed in the introduction, prospect theory assumes that negative information is particularly effective: it is perceived more than twice as strongly as positive information (Kahneman and Tversky 1979). However, if multiple challenges lead to saturation of demand for negative information, positive news may be more effective. For example, messages highlighting the beauty of biodiversity in its broader sense might be more promising. Our findings call for further in-depth qualitative studies to better understand such nuances and more detailed explanations of how multiple societal challenges and positive, negative, and mixed information about them influence individuals at more substantial levels – changing them over time more fundamentally.

4 Discussion and conclusion

Biodiversity loss is one of the key challenges of our time. Yet it is only one of many societal challenges requiring attention and action. Unfortunately, many challenges compete for human attention, and biodiversity loss has received no or very little attention due to the prominence of multiple persistent or new issues in the public discourse. While climate change has long been the most debated and considered challenge in the environmental domain, the Covid-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine have been some of the most prominent issues in the recent discourse that, albeit with important links to the environmental issues, go well-beyond, raising many wide-reaching concerns that might be more salient and urgent in their nature to many individuals.

To shed light on priority given to tackling biodiversity loss in the context of multiple societal challenges, we conducted an experimental study. Our main goal was to better understand how reminders of other challenges – specifically, the war in Ukraine and the Covid-19 pandemic – influence prioritisation given to tackling biodiversity loss. Reminders have frequently been used to steer behaviour and seen as powerful nudging instruments (Sunstein 2014, 2020). Further, guided by several strands of literature on human attention, we explored the effects of communicating information about the causal links between biodiversity loss and the other societal challenges. We find that reminding of additional societal challenges is unlikely to enhance the prioritisation of biodiversity loss (regardless of whether a causal link between the challenges is communicated); if anything, it is more likely to reduce attention to biodiversity. This aligns with the theory of finite pool of attention and our basic intuition that would predict less attention for individual issues with more issues competing for the limited attention, at least on average.

Most importantly, we find that personal importance of biodiversity to individuals was the key predictor to explain priority given to tackling biodiversity loss. In line with the literature on traits such as values, beliefs, attitudes, our finding indicates that combating biodiversity loss requires time for attitudes and values to develop in society, especially as they are embedded in social norms that can counteract prioritising biodiversity (Bergquist et al. 2019). Therefore, it is no surprise that our study finds such variables as education and patience to be important determinants in explaining personal importance of biodiversity. Strengthening biodiversity engagement at structural levels (for example, via education and policy) can be seen as the main recommendation resulting from this study, highlighting limits of nudging and framing. We also observe that the quality of information can have seemingly opposite effects – either by stressing the urgency and importance of the issues and therefore leading to higher prioritisation or by saturating the individuals with the undesired information and therefore resulting in avoidance of engaging with the issue altogether. Ultimately, the extent to which information shapes individual preferences, values, and finally behaviour also depends on existing beliefs and social norms. However, changing social norms (i.e. accepted rules of society) is inherently a collective, not an individual, endeavor (Bicchieri and Mercier 2014; Soliev et al. 2025).

Strengthening biodiversity represents a planetary commons (Rockström et al. 2024) or a global public good (Buchholz and Sandler 2021). Thus, much more research is required to better understand how people perceive multiple challenges and how it affects attention on a global level. Future research should study how varying levels of media attention in different contexts shape biodiversity prioritisation to better understand the implications from our study. Moreover, it is arguably one of the most urgent research tasks to empirically address different social groups that are likely to be exposed to various societal challenges differently. Beyond instrumental values, studies should explore to what extent relational values of biodiversity (Himes and Muraca 2018; Jax et al. 2018) can serve as a foundation or catalyst for improved prioritisation of biodiversity. Similarly, attitudes, values, and narratives are not constant over time. Finally, our study shows the need for more nuanced sub-theories that can capture the interaction between human behaviour and biodiversity, as theoretical concepts such as loss aversion insufficiently explain saturation of negative information, and we need knowledge and theories that better explain decision-making in complexity.

Additional File

The additional file for this article can be found as follows:

Notes

[2] By using the term “war in Ukraine”, we follow the terminology of the “Faktencheck Artenvielfalt” project that deals with the definitions used in the German language (Wirth et al. 2024).

[3] There are some studies in the literature that focus on – in contrast to our paper – the relevance of positive framings (Kidd et al. 2019; Kusmanoff et al. 2020).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the editors and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and criticism. We are particularly grateful to the participants of the XIX Biennial IASC Conference 2023 for their helpful comments.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.