1. Introduction

The design principles for governing the commons lay out conditions under which long-lasting community-based collective action is likely to occur (Ostrom 1990, Cox et al. 2010). However, such collective action can involve significant social inequality, even if all design principles are met (Klain et al. 2014, Oberlack et al. 2015). Notably, commons institutions have been found to disproportionately exclude women (Zwarteveen and Meinzen-Dick 2001). Gender inequality is often deeply rooted in community-based organizations (CBOs) that may be resilient in institutional and ecological terms but at the same time male-dominated and repressive (Agarwal 2007). This is problematic not only because justice and fairness constitute moral values by themselves, but also because CBOs characterized by inequality can gradually erode internal cooperation (ibid.). Approaches in commons research to account for inequalities are currently in full development (Barnett et al. 2020, Kashwan et al. 2021). One research direction explores how different forms of power play out in community-based collective action (Clement 2010, Haller 2019, Kashwan et al. 2019, Morrison et al. 2019, Partelow and Manlosa 2023). A second discourse frames the problem in terms of environmental justice. It has explored how social movements interact with CBOs in environmental justice conflicts (Villamayor-Tomas and Garcia-Lopez 2018, 2021). However, studying the relations between CBOs and environmental justice is still in its infancy. Most studies have focused on settings where conflicts had already escalated to open, often violent confrontations. Less is known, however, on how CBOs can be adapted to overcome structural inequalities.

This study aims to contribute to these research directions in three ways. First, empirically, we analyze the current situation of, barriers to and strategies for environmental justice for women through six case studies in Peru. Second, at a theoretical level, we contribute to theory on community-based collective action through an analysis of environmental justice and value chain inclusion. Third, methodologically, we propose an assessment framework for environmental justice for women in community-based collective action settings. We focus on women in cacao cooperatives because cooperatives constitute widespread institutions for community-based collective action, and the cacao sector faces significant gender inequalities (Kuhn et al. 2023). Three research questions guide our analysis: 1) How is environmental justice for female stakeholders of cooperatives perceived within cacao producing regions? (“EJ assessment”); 2) What factors hinder better environmental justice for their female stakeholders? (“EJ barriers”); 3) What strategies do cooperatives employ to improve environmental justice for their female stakeholders? (“EJ strategies”). We present results from case studies conducted at six selected cooperatives and associations in two Peruvian cacao growing regions.

Section 2 of the article explores relations between gender inequality, cooperatives and environmental justice in the cocoa sector, Section 3 describes our methods, and Section 4 introduces the context and cases in Peru followed by Section 5 presenting the results of the case studies. Section 6 derives an assessment framework with key indicators to evaluate environmental justice for women in cooperatives as well as a discussion of implications for collective action research.

2. Cooperatives and environmental justice for women

2.1. Cooperatives, inclusive value chains and gender

A cooperative is “an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly-owned and democratically-controlled enterprise” (Saarelainen and Sievers 2011: 6). Cacao cooperatives facilitate collective action among producers for increased participation in value chains. They do so by promoting collective activities such as post-harvest processing, logistics, trade or marketing (Blare et al. 2017). The collective bargaining power of cooperatives can strengthen producers’ market position vis-à-vis buyers (Oberlack et al. 2023). They also facilitate natural resource management of smallholders through training, access to inputs, credit, market information, technical assistance, and cooperatives often implement standards for certifications (Bijman et al. 2016). However, land for cacao cultivation is predominantly held privately by smallholders (Voora et al. 2019). Asymmetries of control, benefit and access can persist, and cooperatives are embedded in larger systems of production, such as value chains (Oberlack et al. 2020). Therefore, cooperatives may deviate from a view of commoning among fully equal (land) users.

Specifically, women have been found to participate less in agricultural value chains and cooperatives (Kuhn et al. 2023). Even where value chains and cooperatives provide opportunities for women, their activities, remuneration, positions and working conditions are often inferior to those of men (Bamber and Staritz 2016; Wijers 2019). Often, women’s participation in value chains remains invisible as their activities are more likely to be unpaid, home-based or informal (Bacon et al. 2023). Cooperative’s internal institutions influence how benefits of value chain participation are captured and distributed (Stoian et al. 2018). Therefore, effectively including women continues to be a major challenge for many cooperatives (Anan 2018).

Multiple barriers limit women’s inclusion in (cacao) cooperatives and value chains. Most of them arise from gendered social norms that manifest at the individual, household and community level as well as within the wider political context (Brislane and Crawford 2014). Main barriers can be clustered into the categories lack of access to resources, time constraints, lack of decision-making power, and lack of network (group participation), as summarized in Table 1. Stoian et al. (2018) note that often, value chain participation is erroneously conceived as an individual choice made by women, failing to recognize that such decisions are mostly taken at the household level based on trade-offs between different income generating and domestic activities. Sometimes, greater value chain participation simply leads to higher workloads for women while additional income is still controlled by male family members (Coles and Mitchell 2011). Thus, cooperatives may contribute to women’s empowerment by implementing measures addressing underlying formal and informal social norms that lead to discrimination as well as strategies addressing the barriers cited above more specifically (World Cacao Foundation 2019).

Table 1

Barriers to women’s inclusion in value chains and their participation in cooperatives.

| BARRIER | DESCRIPTION | SOURCES |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of access to resources | Reduced access to: a) land, markets, income, credits, livestock, agricultural equipment, b) education, skills, information, c) infrastructure, services | 1, 2, 3, 4 |

| Time constraints | Responsible for domestic and care work, less or no time for paid labor, women have an overall higher workload | 1, 3, 4, 5 |

| Lack of decision-making power | Lower negotiation and decision-making power on all levels, e.g. household expenditures, labor activities, production decisions | 2, 4, 6 |

| Group participation | Lack of networks because of limited participation in economic or social groups or the community, especially in leadership roles | 1, 4 |

[i] Sources: 1) Bamber and Staritz 2016; 2) Coles and Mitchell 2011; 3) Stoian et al. 2012; 4) Anan 2018; 5) Brislane and Crawford 2014; 6) Stoian et al. 2018.

2.2. Environmental justice and gender in the cacao sector

Dominant interpretations in the environmental justice literature offer a three-dimensional perspective for assessing justice claims in accessing, using or protecting the natural environment. These dimensions are distributional, procedural, and recognition justice (Fraser 2000, Schlosberg 2009). In our study, the environmental resource of main interest is land used for cacao production and associated post-harvest processes and value chains.

Fraser (2000: 116) defines the distributional dimension of justice as the “allocation of disposable resources to social actors” resulting from a specific economic system. Martin et al. (2016: 1) describe distributional justice as the “differences between stakeholders in terms of who enjoys rights to material benefits and who bears costs and responsibilities”. The procedural dimension assesses “how decisions are made, who is participating and on what terms” (Martin et al. 2016: 1). For Fraser (2000), procedural justice means parity of participation in social life among relevant social groups as superordinate result of distributional and recognition justice. There are different forms of participation that determine the degree of procedural justice. Participation can mean having appointed representatives in decision-making bodies without any real interaction or decision-making power of the people affected. At the other end of the spectrum, participation can mean a real transfer of authority and responsibility to the people concerned (Martin et al. 2016). Questions of recognition justice have been relatively neglected in environmental justice studies (Schlosberg 2009). Misrecognition is a ‘status injury’ (Fraser 2000) that constitutes not only a cultural depreciation but can make parts of society “comparatively unworthy of respect or esteem” (Fraser 2000: 114).

Across these three inextricably linked dimensions of environmental justice, most research has focused on the two factors race and/or class, paying less attention to the role of gender (Gaard 2017, Lecoutere 2017). In the cacao sector, gender inequalities relate to “limited access to training, inputs, credit and land” and “routinely unpaid and undervalued” work of women (World Cacao Foundation 2019: 3). Even though women in cacao producing families are normally responsible for all domestic and care work, they often also contribute considerably to cacao production (Blare et al. 2017). Nonetheless, women are typically less informed about farming practices and markets and their decision-making power can be limited (Blare et al. 2019).

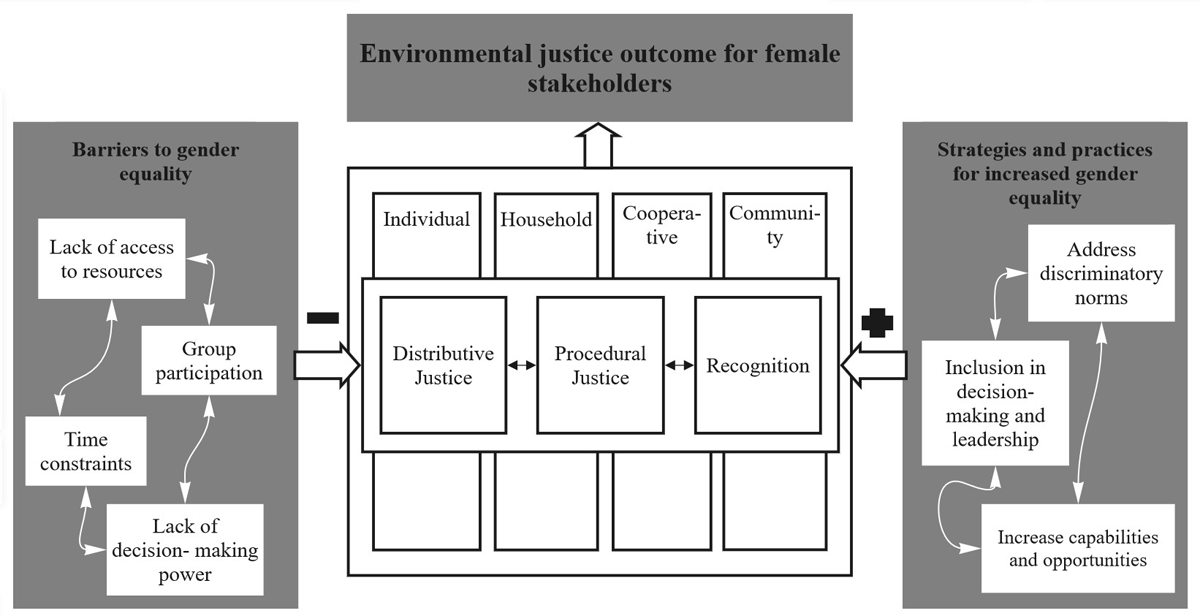

Figure 1 summarizes the analytical framework developed for this study based on the above review. We conceptualize environmental justice for women related to the environmental good of cacao as gender equality on three non-hierarchical dimensions: the distribution of benefits and burdens, participation in decision-making, and recognition. Environmental justice situations are constrained by barriers to women’s inclusion, whereas strategies can improve such situations by influencing the three interacting dimensions of distributional, procedural and recognition justice at the individual, household, cooperative and community levels.

Figure 1

“Analytical framework. Source: Authors”

3. Research design and Methods

We employed a multiple case study research design to obtain results that represent a variety of local contexts (Yin 2013). We address the research questions based on qualitative data as this allows us to gain an understanding of subjective experiences and social processes (ibid.). The gendered environmental justice assessment of cooperatives as well as the analysis of strategies for, and barriers to, gender equality require an in-depth understanding of the context and insights from various perspectives. Therefore, we included a range of female actors including official cooperative members, partners of associated farmers, and cooperative employees, but also male stakeholders. We purposely selected organizations using the following criteria: (a) different sizes and age of the cooperatives, (b) different proportions of female members, (c) accessibility and interest to participate in the research. This led us to select six producer organizations – five that are legally registered as cooperatives and one as association.1

The first author collected data through 41 semi-structured interviews in Spanish during seven weeks of fieldwork in 2021 (Table 2). The number of interviews per cooperative varied between four and fourteen. The questionnaire was based on the analytical framework and covered (on all four levels) the current situation in terms of distribution, participation and recognition in accessing and using land for cacao production; the barriers for participation of women in cacao value chains; the strategies of the organization for women inclusion; as well as background information about the producer organization. We identified interviewees by consulting cooperative representatives. Interviews lasted between 30 and 90 minutes and were recorded with the consent of the interviewees. We complemented this primary interview data with field observations, reports, websites and scientific literature.

Table 2

Interview groups and number of people interviewed.

| INTERVIEW GROUP | DESCRIPTION | NUMBER |

|---|---|---|

| Manager | Person with a management or other leadership position within the cooperative, normally the general manager. | 7 |

| Female employee | Women working for the cooperative in any function, including in stockpiling. | 8 |

| Male employee | Men working for the cooperative in any function, including in stockpiling. | 5 |

| Female producer | Women who are either an official member of the cooperative or the partner of a male official member. | 12 |

| Male producer | Men who are either an official member of the cooperative or the partner of a female official member. | 9 |

We transcribed the interviews and analyzed them through qualitative content analysis using MaxQDA 2022 software (for the codebook, see Appendix A). In addition to predefined categories derived from the conceptual framework (Figure 1), additional categories were created using an open coding approach based on the data. The analytical results were shared with and validated by the research participants.

The following limitations need to be taken into account when interpreting our results: Our positionality as researchers and our analytical framework (Figure 1) influenced how this research was conducted, the questions asked and how the responses were interpreted. The author group included female and male researchers from Peru and Europe. Having equal rights and opportunities for all genders was an important value that underpinned this research. This implies that individuals can make their own life choices, get the chance to develop themselves as human beings, are valorized by the people around them and are given the opportunity to gain an understanding of the context they live in. This conceptualization of gender equality means that we may have interpreted situations differently than our interviewees. Second, our sampling approach may have affected the representativeness of the interviewees. For instance, the interviewees may have been chosen because they were especially aware of gender topics or especially collaborative with the cocoa cooperative. We may also not have been directed to particularly marginalized people. Third, social desirability biases as well (perceived) power imbalances may have affected interviewee responses. Finally, questions about self-perception, roles and habits inside a family are personal; therefore, and in line with informed consent, interviewees may have retained certain personal information that would have been relevant for the aims of study. Despite those limitations, we argue that this study holds relevant insights about the current situation, barriers and strategies for environmental justice for women in cacao cooperatives.

4. Context and Cases: Cacao Cooperatives and Gender in Peru

4.1. Context

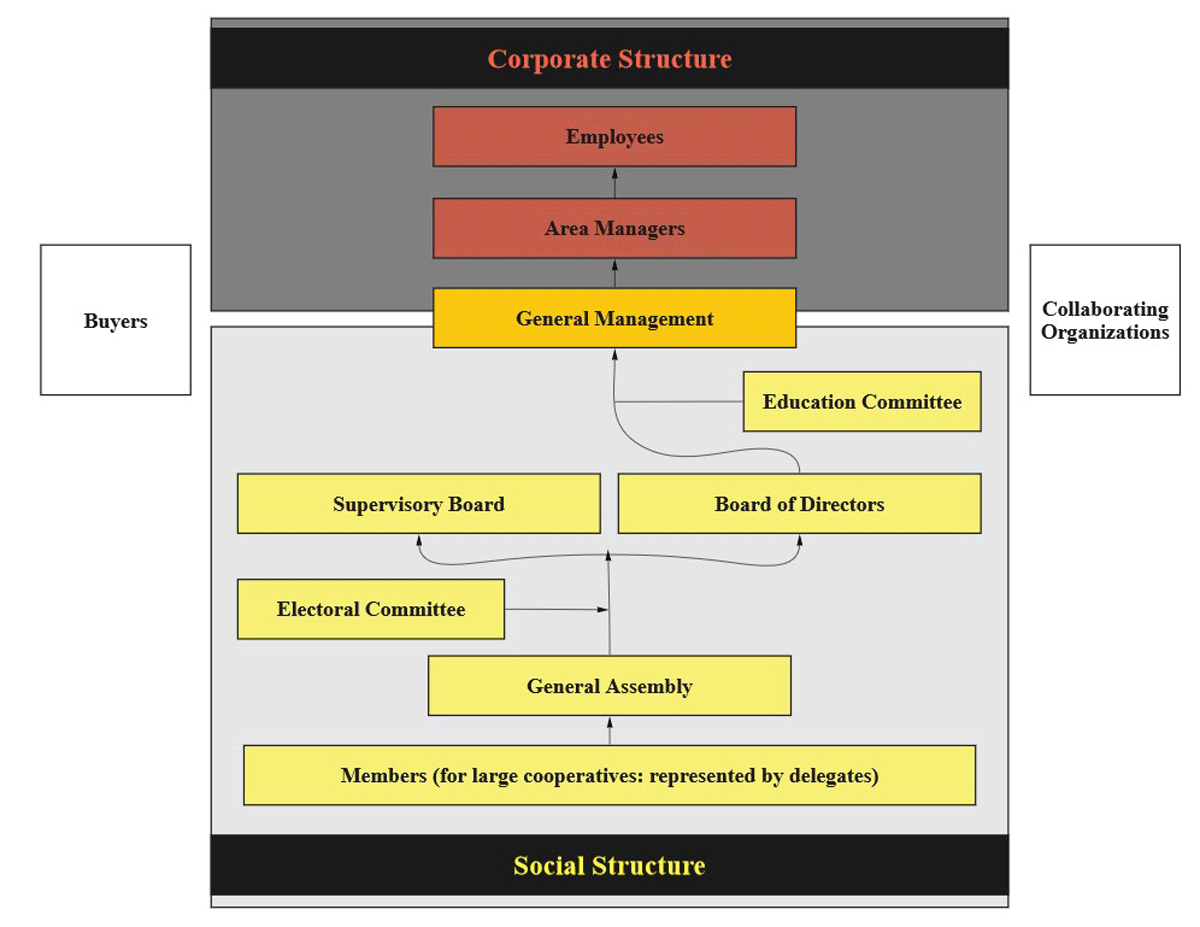

Peru is the eighth largest cacao producing country globally (Fountain and Hütz-Adams 2020). The country is known to produce some of the finest cacao varieties (Thomas et al. 2023). More than 89’000 farmers rely on the cacao sector (MIDAGRI 2023). Over 90% of Peru’s cocoa is produced by small-holder farmers with an average farm size of two hectares (ibid.). About 35% of Peruvian cacao producers are organized in cooperatives (Wiegel et al. 2020). Cooperatives typically adopt a dual structure with a social and a business part (Figure 2). The general assembly is the highest decision-making power, it also elects the members of committees and boards. The general management reports to the general assembly. The price at which cooperatives buy the cacao from their members is based on the market value and varies according to qualities, varieties, certifications and buyer-specific components. In addition, producers typically receive a volume-dependent premium at the end of the year. Producers generally deliver their cacao in pulp to collection points and the cooperative takes care of the fermentation, transport and commercialization of the beans.

Figure 2

“Typical dual structure of cacao cooperatives in Peru with a social and a corporate part. Source: own work based on organigrams shared by the cooperatives under study.”

The Peruvian Cooperative Law regulates the nature, governance structure, rights and obligations of cooperatives. In 2021, an amendment of this law introduced two changes for women’s inclusion. Article 8 stipulates the possibility for couples to be considered as one member of the cooperative. Article 10 states that: “Agricultural user cooperatives promote the active participation of women on equal terms with men. […] The users’ agricultural cooperatives try to include in their governing bodies a number of women that will make it possible to reach, within five years from the entry into force of this law, a presence of women and men proportional to the number of members that make up their membership” (Ley de Perfeccionamiento de La Asociatividad de Los Productores Agrarios En Cooperativas Agrarias 2021, own translation).

The development of cooperatives in Peru has proven difficult, especially owing to issues of weak business management, corruption, mistrust with buyers and members, or lack of working capital (Blare et al. 2017). Many cooperatives still rely on subsidies from projects, governments or sometimes buyers to cover the costs for service provision (Blaire et al. 2017). Even though women actively participate in cacao production, they have little influence in decisions on the marketing of cacao as well as purchases or sales of land and farm equipment (Blare et al. 2019). Ramirez et al. (2021) found that the production steps holding the highest potential for women’s inclusion are grafting and nursery, drying and fermentation of cacao beans as well as the production of cacao derivatives.

4.2. Cases

Table 3 characterizes the six organizations that we selected for the present study. They are located in the tropical region San Martin and in the region of Piura with a seasonally dry climate. The cooperatives vary in size and age. They all offer technical assistance, trainings and workshops to their members as well as different additional services. Most of the cooperative members are native Spanish-speakers, while especially one cooperative has a significant part (53%) of members speaking Quechua as their first language. The share of female cooperative members and employees ranges between 12 and 37%, and between 12 and 100%, respectively, while the share of women in leadership positions was generally low but varied.

Table 3

Description of the selected cooperatives and producer association.

| COOPERATIVE 1 | COOPERATIVE 2 | COOPERATIVE 3 | COOPERATIVE 4 | COOPERATIVE 5 | ASSOCIATION 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Founding year | 2015 | 1997 | 2013 (started in 1995 as association) | 2003 | 2016 (as cooperative) | 2009 |

| Products | Cacao | Cacao (main product) and timber To a lesser extent hot peppers, Tahiti lime and ginger | Coffee (75%), panela (since 2003),2 cacao since 2006, carbon credits from reforestation (since 2010) | Cacao Cacao derivatives: chocolates, liquor | Cacao Cacao derivatives: chocolates, Theobroma bicolor, cacao pulp derivatives | Chocolate, roasted majambo (Theobroma bicolor), chocolate from majambo, majambo and cacao liquor |

| Cacao production | 25 t3, min. farm size: 3ha | 4 000 t, min. farm size: 2ha | 1 000 t4, min. farm size: 0.5ha | 50 t, min. farm size: 0.5ha | 860 t, min. farm size: 1ha | N/A |

| N° of members | 40 | 1850 (average 2 000) | Overall: 6 500, cacao: 900 | 152 | 460 | N/A |

| N° of employees | 8 | 60 | 138 | Fix contracts: 7 Per hour basis: 3-5 | 21 | 15 |

| % female members | 37% (15 out of 40) | 20% (320 out of 1 850) | 20% | 20% (30 out of 152) | 12% | N/A (association with employees) |

| % female employees | 12.5% (1 out of 8) | 33% (15 out of 45) | 30% | 40% (fix contracts), 50% (overall) | 33% | 100% |

| Women in leadership positions | Social structure:

| Social structure:

| Social structure:

| Social structure:

| Social structure:

| All-women association |

| Services provided to members |

|

|

|

|

|

|

5. Results

Overall, we find that women benefit less than men from cacao value chain integration through cooperatives. Furthermore, misrecognition of women’s contributions and capabilities prevails. Such inequalities are mainly due to social norms preventing women from actively participating in cooperatives. However, our results also demonstrate that cooperatives are effectively developing strategies to increase women’s inclusion in community-based collective action.

5.1. Environmental justice assessment

The CBOs in our sample influence and are influenced by distributional, procedural and recognition justice at four levels: cooperative, household, individual and community.

5.1.1. Cooperative level: female cooperative members

Participation of women within the cooperatives and attention given to women’s inclusion in cacao value chains has generally increased over the past years. While all cooperatives make efforts to enhance gender equality, they are currently at different stages, as the following indicators show.

First, the percentage of official female members varies considerably among the cooperatives, ranging from 12 to 37%. A significant part of the female members is single or widowed. Some of the local producer committees do not have a single female member. This is important since normally only official members of the cooperative are eligible for mandates and credits, have the right to vote, and are invited to meetings and training.

Second, gendered differences in attending cooperative events prevail. While our respondents reported that women are less involved, they claimed that generally, their participation tends to increase. Most respondents stated that “in general it is the man and if he cannot, it is the woman5” who attends meetings and trainings. In cooperative 1, women account for 40-50% of participants, but other cooperatives reported difficulties in increasing women’s attendance. However, female respondents often stated that they would like to be more involved. Likewise, cooperatives encourage the participation of both heads of households. Nonetheless, most interviewees, men and women, did not see it as a goal for both to be equally knowledgeable about the cooperative and cacao production. Furthermore, the forms of participation matter. Few women participate in technical training, while their attendance is higher for general meetings. Interviewees also said that sometimes women are sent to meetings by their partners but are not supposed to take decisions or accept mandates. Some respondents stated that women speak up less often than men and are more afraid of exposing themselves through active participation. It was also said that often, women do not “feel capable of assuming a mandate.6” Other respondents stated that women are as active during meetings as men and sometimes even more than them. Attendance in meetings and training is relevant for procedural as well as distributional justice as this is where decisions are taken, producers are informed about current issues within the cooperative and the sector, and where women can develop their skills. It also has an indirect effect on recognition, as being informed and skilled increases an individual’s self-esteem and how the person is perceived by others.

Third, women are underrepresented in leadership positions within the cooperatives’ social structures. None of the cooperatives in our sample has ever had a female president and only one has a female vice-president. The cooperatives, through the national cooperative association of APPCACAO, have promoted the national network of women cacao producers. On the initiative of the members’ wives, the network has worked to make the participation of women visible and promote the generation of added value from the production of cacao and other crops through micro-enterprises that support the family economy.

5.1.2. Cooperative level: female employees of cooperatives

First, the share of female employees in the cooperatives varies between 12 and 50%, if the women producing derivatives paid on a per-day basis are counted.7 As a special case, Association 6 is an all-women enterprise. Women employment contributes to the cooperatives’ effects on individual income, skills, recognition and self-esteem.

Second, a clear pattern emerges regarding the areas in which male and female cooperative employees were active. Most technical assistants working in the field are men, while women are mostly found in the areas of accounting, finance, secretariat, assistant positions and producing cacao derivatives such as chocolate. Some cooperatives also employ female members as stockpilers.

Third, women are underrepresented in corporate leadership positions, especially at senior levels. Women are often occupying important lower management positions, mainly as heads of areas of credits and treasury, or accounting and finance. For one cooperative, even most of the area managers are female. Even though female employees generally feel equally valued as their male counterparts by superiors and colleagues, the overall underrepresentation of women in corporate leadership positions, especially at the top level, is a sign of misrecognition of women’s capabilities. Talking about the topic, one woman stated that “the most important positions are held by men, so I believe they think that women can’t do them.8”

Fourth, except for one interviewee, employees and managers claimed that there is no difference in salaries between women and men working in the same position. However, the fact that men are more likely to occupy high-level positions also means that on average they get paid more. Additionally, for production of derivatives where the share of women is highest, the contract conditions are most precarious. The salary corresponds generally to the minimum wage paid on a per-day basis and the working hours depend on demand.

5.1.3. Household level

First, tasks and activities related to cacao production and the cooperative are mainly carried out by men while women are mostly involved in the production of cacao derivatives. Nevertheless, many interviewees also highlighted the importance of women for the cacao production, but their role was generally framed as a supporting “pillar” and not an equal contributor. Women are mainly responsible for bringing lunch to their partners working in the field but some are also very involved in the field work and conduct all tasks, also thanks to the training provided by cooperatives.

Second, most income is used in ways that benefit the entire family, in particular for basic needs such as food, health or education. In some reported instances, the man delivered the cacao, received the money and spent it for himself while the woman had to make ends meet with what she received from her partner. However, this does not seem to occur often, and several women producers said that they deliver the cacao together and they know the income.

Third, cooperatives support their members through training and extension services. Since it is mostly the men working in the field, extensionists engage more with them than with women. Most cooperatives offer special programs targeting women, such as training and support for planting vegetable gardens for self-supply and sales since in most households, women are allocated a small plot of land for vegetable farming. Lower female participation in training does not automatically imply that women were not informed. Several respondents said that the person participating in training informs the other afterwards. Nevertheless, women overall have less access to information about the cacao sector and functioning of the cooperative due to their limited participation. While many cooperatives provide access to credit for members, it is only destined for investments in cacao production. Credit cannot be taken out to start or improve the production of cacao derivatives, thereby making the credits less beneficial for women. Additionally, only the official member of the cooperative is generally eligible for credit. Another service offered by cooperatives is support programs in case of health issues or death. These benefit the entire family and make no distinction between official member and partner.

Fourth, decision-making power within the household is an indicator for procedural justice. Most producers stated that in general, decisions are taken jointly within their households while cooperative managers and employees claimed that decision-making power in the household mainly lies with the men, especially in producers’ households. Regarding land use and cacao production, decision-making is generally up to the man but none of the female producers stated that they would prefer other land uses when asked about it. In most households, the land belongs to the man, but independent of the land ownership, the main responsible for the cacao production is the male producer. Several interviewees suggested that if women earn their own income, they also have more decision-making power within the family. One stated that “the woman who brings bread to the house also has a greater role to play.9” In many families, it is the women who administers the money. Several male interviewees mentioned that their partner was better with money and that they therefore prefer leaving it to them to decide how to spend the household income. In other cases, the women receive specific amounts from their partners for household expenditures.

Finally, cooperatives can affect recognition among household members. While women are typically less valued than men according to our interviews and observations, several respondents claimed that there is less machismo and gender-based violence in the member families than in average households in the community because of the awareness-raising efforts done by the cooperative. They observed that men participated more in housework and women’s opinions were more respected. While some respondents claimed that women’s involvement in the cooperative has no effect on the interactions within the household, several interviewees stated that women’s increased self-esteem from active participation in the cooperative improves their recognition within the family. Additionally, the fact that more women take over mandates within the cooperatives indicates changes in how women’s roles and capabilities are perceived.

5.1.4. Individual level

Our interviews suggest that self-esteem is a critical dimension for recognition and procedural justice. Women who generate their own income demonstrate generally more self-confidence in the way they talk but also regarding their position within the family and the respect they demand from other family members. However, it is uncertain whether income opportunities lead to higher self-confidence or if women who are already self-confident are more likely to start their own business or income-generating activity. For instance, all women starting Association 6 were already leaders in another local organization. Similarly, one of the women working in the production of derivatives stated that she had joined a local women’s group before where she had learnt to value herself more and demand more respect from her partner. Better self-esteem and generating income are therefore most likely two mutually reinforcing factors.

Involvement in cooperatives and associations enable some of the women to travel to the capital and even to other countries – places they would normally not be able to visit. Some won important prizes for their chocolate and are sought-after interview partners. All this makes a big impact on how the women involved perceive themselves and how they are perceived by others, including their families. Employees with university degrees also reported that working for the cooperative increases their self-confidence and helps them in their personal development, experiencing new gender roles working with the cooperative.

5.1.5. Effects at community level

Cooperatives influence the larger communities in several ways. First, by involving women within the organization, having them in leadership positions, and enabling them to travel, cooperatives break with traditional gender roles, send a signal to the community that women’s inclusion is important, and show what women are capable of. Women who are empowered through the cooperative are more likely to be involved in other community activities and make other women aware about their rights and capabilities. Second, some cooperatives implement programs about gender equality and other social issues that target the community at large. Third, cooperatives can provide job opportunities for women which are otherwise hard to find in rural areas.

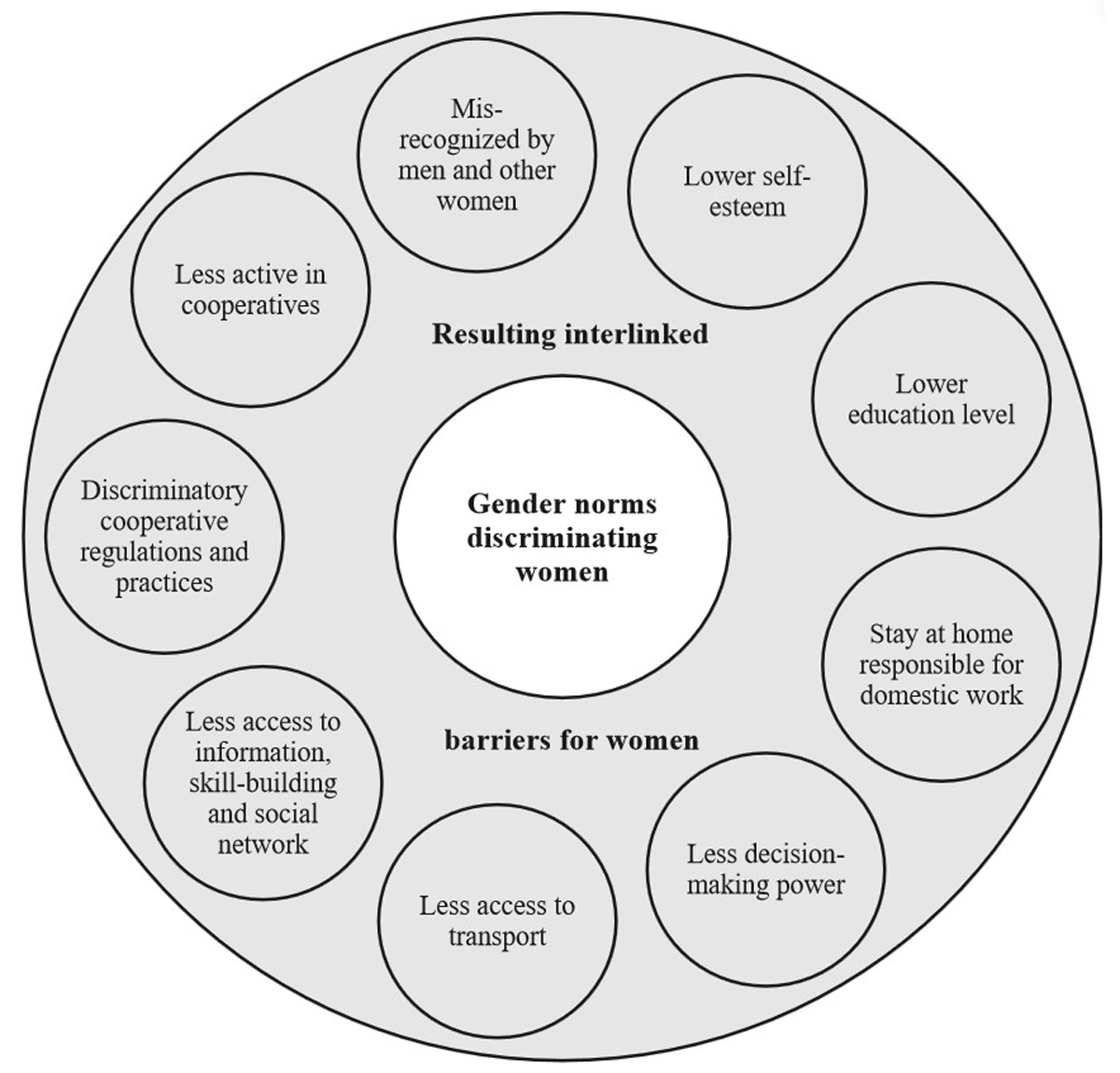

5.2. Barriers to greater environmental justice for women

The environmental justice situation described in the previous section reflects gendered social norms. These norms manifest themselves in intertwined barriers that underpin the persistence of inequalities (Figure 3). The social norms are clearly expressed in the roles of women and men within families and society. Typically, men are the heads of the family and responsible for the work outside the house and women are responsible for care and domestic work. Since women are thus generally less involved in the cacao production, it also makes less sense for them to participate in cooperatives’ activities. The fact that women participate less further aggravates the unequal distribution of knowledge, making them even less likely to join further meetings. Several female producers said that they do not feel comfortable actively participating because they do not feel knowledgeable enough or because a large majority of male participants in meetings discourages them to speak up. This creates a self-reinforcing lock-in effect in a sense that as long as only few women participate, it is not attractive for more women to join.

Figure 3

“Barriers to environmental justice for women in cacao growing regions. Source: Authors.”

Several female interviewees stated that other than to go to the field, they rarely leave the house, limiting their social participation and opportunities to gain knowledge about the “outside world”. Given the traditionally domestic centered role of women, it is socially ill-regarded if they spend time or work outside. However, many female producers stated that they are content with their situation but want it to be different for their daughters. Women’s participation in social life and cooperative activities is further hampered by a lack of access to transport, as the use of motorbikes is mainly reserved for men. As women’s role in the family is the domestic work, it was for a long time not seen necessary to send them to school. The generally lower education level of middle-aged and older women as compared to men of their age is another factor limiting their participation in the cooperative. Several cooperative representatives said that it is at times difficult for female producers with little school education to learn new things in training, especially if they are illiterate. The difference in education is likely to affect self-esteem and access to resources.

One of the main barriers to environmental justice in the study context is the lack of recognition of women’s value and capabilities by themselves and others. Female professionals generally are recognized within the Peruvian society, the cooperative and within their households. This is different for female producers, not only in terms of roles and recognition within the family but also with regards to their self-esteem. Sometimes, both partners believed that women’s intellectual capability is inferior to men’s, only men are considered competent to take decisions, and women do not need to be involved in social life. This affects women’s aspirations at the household, cooperative and community level and even leads them to judge other women that seek to break out of traditional gender roles. Several respondents reported that women have higher overall workloads especially if they are single mothers. Nonetheless, the contribution of women to the family is not always acknowledged by their partners or themselves. However, some male producers clearly stated that they see their partner, and women in general, as equal and even superior in certain aspects and it showed in the way they interacted. The woman had the space to speak, make propositions and take decisions. However, in other instances interviews suggested that gender inequalities are present. In such cases, the man answered questions asked to his partner during introductory conversations and she stayed in the background.

It is also a wide-spread conception within the Peruvian society that men are more suitable for leadership positions, even though this is changing slowly. This is reflected in the underrepresentation of women in leadership positions within the cooperatives’ social and business structures. Female respondents in leadership positions reported that it was hard at the beginning because people were skeptical if a woman is capable of filling “typically male” functions.

Those barriers adversely affect all three dimensions of environmental justice with relation to cacao production. The gendered social norms and roles prevent women from participating (procedural justice) in cooperatives and thus from benefiting from skill-building and access to information (distributional justice). They are perceived by themselves and others as less entitled and capable of taking decisions, especially regarding cacao production and the cooperative (recognition and procedural justice). Cooperatives’ regulations that give more rights to the generally male official member (procedural justice) reflect and reinforce those social norms.

5.3. Strategies and practices for environmental justice for women

All cooperatives in our sample promote gender equality. While the cooperatives seem to be intrinsically motivated to promote the inclusion and the role of women for social and economic reasons, many had started their efforts because of external pressure from certification standards or buyers.

We identified 18 strategies and practices that they adopt to improve the situation for their female stakeholders in terms of distributive, procedural and recognition justice of cacao land uses and value chains. The overview in Table 4 shows that no organization adopts all the strategies. Some strategies address clearly the distributive, participatory or recognition dimension of environmental justice and one specific level of impact, whereas others address multiple dimensions and levels. We summarize the strategies and practices in the following.

Table 4

Strategies to improve environmental justice outcome for female stakeholders by cooperative/association.

| STRATEGY | EJ* | LEVELS** | COOP. 1 | COOP. 2 | COOP. 3 | COOP. 4 | COOP. 5 | ASSOC. 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training and awareness raising | |||||||||

| 1 | Workshops and other inputs about gender equality | D, P, R | 1, 2, 3 | ||||||

| 2 | Specific trainings/internships/projects specifically for women | D, P | 1, 2 | N/A | |||||

| 3 | Highlight the importance of gender equality and women’s participation during regular cooperative events | R | 1, 2, 3 | N/A | |||||

| 4 | Trainings that increase women’s understanding of general issues | D, P, R | 1, 2 | ||||||

| 5 | Special trainings for female employees of cooperatives | D | 1 | N/A | |||||

| 6 | Gender workshops/speeches for externals | D, P, R | 3 | ||||||

| Economic opportunities | |||||||||

| 7 | Create income opportunities for women in cacao value chain | D, P, R | 1, 2 (3) | ||||||

| 8 | Create income opportunities for women in other value chains/activities for self-consumption | D, P, R | (1) 2 | ||||||

| Communication | |||||||||

| 9 | Showcase women’s contribution in communications | R | 1 | ||||||

| 10 | Awareness raising during externally organized events | D, P, R | 3 | ||||||

| Participation | |||||||||

| 11 | Facilitate attendance and encourage the active participation of women in cooperative events | P, R | 1, 2 | N/A | |||||

| 12 | Send female representatives to external events | D, P, R | 1, 2 | ||||||

| Cooperative rules | |||||||||

| 13 | Transparent salary grid | D, P | 1 | N/A | |||||

| 14 | Institutionalized measures against sexual harassment within the cooperative | R, P | 1 | ||||||

| 15 | Gender equality as organizational culture (voice, treatment, invitation to events, leadership positions) | R (D, P) | 1 | N/A | |||||

| 16 | Health and death insurance | D | 2 | ||||||

| 17 | Establish quota for women in leadership positions | D, P, R | 1 | N/A | |||||

| 18 | Increase the rights for partners of official members | P | 2 | N/A | |||||

[i] Colors: White = strategy not implemented, Dark grey = strategy implemented, Bright grey = contradictory information.

*Environmental justice dimensions: D = Distributional justice, P = Procedural justice, R = Recognition.

**1 = Cooperative, 2 = Household/individual, 3 = Community.

5.3.1. Training and awareness raising

All cooperatives conduct workshops to increase gender awareness among their members, and some also do speeches about the topic. Most workshops involve both men and women together, even though men were less interested to attend. Some cooperatives organized events for women only, often aimed at increasing women’s self-esteem. Most gender workshops are organized in collaboration with NGOs or certification organizations. The main topics addressed are the valorization of women, their capabilities and contribution to the family and cooperative, domestic violence, women’s rights, gender roles within the family especially regarding house and care work, and the importance of having women in leadership positions. Exchanges about the participants’ personal experiences is a key element. The workshops often aim to raise participants’ awareness of patterns within their partnerships that discriminate against women and exemplify traditional machismo gender norms. Many cooperative representatives as well as producers stated that such workshops can lead to changes, in particular if they provoke emotional reactions and engagement.

Considering that women’s formal education was often lower than men’s, several cooperatives also offer sessions on general topics such as the functioning of the cacao sector, financial planning for families, accounting, health or the importance of school education for all children. Cooperative 2 also introduced mandatory training for its female employees to increase their skills and enhance their careers. Changing gender norms needs continuous efforts. Several cooperatives therefore integrate gender equality as a transversal topic in their activities. However, even producers who said that their cooperative constantly mentions that both should attend the meetings stated that normally just one of them participates.

5.3.2. Economic opportunities

Several respondents claimed that by having an income, women have more voice in the household and increase their self-esteem. Additionally, increased family income can reduce tensions arising from a lack of money and therefore prevent domestic violence. Some cooperatives include the production of cacao derivatives as a business field, aiming explicitly to offer income opportunities for women. Others support independent local women’s groups with training, credits or equipment for derivative production. Cooperative 3 also has a segmented program, in which they collect beans only from associations of female producers, which is met with interest by buyers willing to pay extra. Some cooperatives implement programs helping women to generate their own income beyond cacao or to produce goods for self-consumption. For instance, they actively involve female producers in their reforestation programs or support women to start breeding poultry or create vegetable gardens.

5.3.3. Communication and marketing

Several cooperatives explicitly recognize the contribution of their female producers in corporate communication or marketing. For instance, one cooperative dedicated each type of chocolate in a series to one of their female members. Another one produced a video showcasing female leaders and producers and asked a female producer association to present their success story in international fairs. By presenting their stories at public events and parades, Association 6 raises awareness about gender equality and shows the community what a group of dedicated women can achieve. To do so, they even created songs about women’s rights and empowerment. Such efforts are not only beneficial to the valuation of women but are also a successful marketing strategy with buyers and consumers.

5.3.4. Participation

Several cooperatives explicitly invite both women and men to events and motivate their members regularly to attend together. To promote active participation of women during cooperative events, two managers mentioned that they directly ask them questions during events, make them present group results and reward them for participation. Another cooperative visits member families regularly; during such visits they motivate female producers to join cooperative activities. They also encourage participation by providing food for 4–5 people per family during events, so women do not have to stay home to cook. Recognizing that oftentimes, women do not attend meetings because they need to take care of the children, Cooperative 1 has put childcare service in place during assemblies. Additionally, the cooperative tries to facilitate the participation of illiterate female producers by relying more on graphs and illustrations rather than text during events, as well as by generally tailoring the communication to make it understandable for them.

In general, cacao farmers often do not have the resources to travel much and many women rarely even visit the nearest town. By sending female producers to external events, cooperatives offer them possibilities they would otherwise never have. Getting out of the familiar context, meeting new people, and seeing different life realities of women enable them to gain new perspectives and increase their self-esteem. Therefore, many cooperatives made it a rule to also send women to expositions or external workshops taking place at the regional, national, and even international level.

5.3.5. Cooperative norms

Cooperative regulations can perpetuate gender inequalities when rights are reserved to male official members (Nippierd and Holmgren 2002). Lately, several cooperatives changed their regulations to strengthen the voting and access rights of the partners of official members. Cooperative 3 requires the signature of both heads of the family for credit applications, making sure both know and approve it. To address the underrepresentation of women with mandates, all cooperatives have introduced a quota or a target for the share of female producers in leadership positions. For instance, cooperatives 1 and 4 aim at having 50% women in the management board. In cooperative 3, local committees with more than one delegate must have at least one female delegate. As they are both Fairtrade certified, cooperative 2 and 5 are required to have female members in their management boards.

Several cooperatives have started adopting a reflective organizational culture to self-assess whether the cooperative actually “lives” gender equality for their female stakeholders. Making gender equality an organizational culture means that the opinions and capabilities of women are respected, top-management practices these values, and women are perceived as equally suitable for leadership positions as their male colleagues. In terms of salaries, one cooperative makes its salary grid transparent to assure that employees earn the same according to their position regardless of gender. Another strategy is to avoid salary gaps between typically female and typically male positions.

Cooperative 3 has a committee for the prevention of sexual harassment in the workplace. In some cases, women supported each other through difficult times, including partners prohibiting them from participating in the cooperative or cases of domestic violence. When learning about such incidents, they went as a group to bring the partner to reason. This is a recognition of women’s right to physical and psychological integrity and also contributes to procedural justice.

6. Discussion

6.1. Environmental justice for women, value chain inclusion and community-based collective action

Here, we propose an innovative approach of connecting environmental justice, value chain inclusion and collective action theory in order to diagnose inequalities in CBOs and identify strategies used to address these dimensions. One current frontier in collective action theory is to account for inequalities in resource use and governance (Kashwan et al. 2021). To this end, environmental justice offers analysts a three-dimensional conceptualization of justice related to environmental resources (Schlosberg 2009). However, environmental justice research has mostly focused on situations of movements of resistance to oppression, on displacement and on resource conflicts (Villamayor-Tomas and Garcia-Lopez 2018). By studying inclusion of women in value chains through cooperatives, we have extended this focus beyond resistance movements. We argue that this framing of environmental justice (rather than injustice) is relevant to broaden the lens of environmental justice research to solutions that prevent rather than remedy environmental conflicts. The focus on the terms of value creation and inclusion in value chains can support this shift in perspectives of environmental justice. Specifically, our analysis provides several insights for community-based collective action.

First, our results demonstrate that cooperatives can be spaces of collective action to tackle some of the structural barriers to gender equality. The strategies employed and their effects are not limited to institutions within CBOs only, but they address (in)justices at multiple levels: cooperatives, household, individual and wider communities. Cooperatives can contribute to women’s empowerment by providing access to resources and group participation. Cooperatives can create labor and leadership opportunities for women, provide information and training as well as production inputs or infrastructure. These strategies can also heighten women’s agency at the household and community level (Stoian et al. 2018). However, the same barriers that limit women’s participation in value chains in general can also prevent them from accessing and benefiting from cooperatives since becoming a member – and especially taking over leadership roles – often requires a certain level of education or resource endowment (Anan 2018, Kuhn et al. 2023). To provide tangible benefits from value chains to women, cooperatives thus have to address those underlying issues of inequality.

Second, inequality can persist in CBOs even if they fulfill all eight design principles for governing the commons, which are a key element of the established theory of community-based collective action (Ostrom 1990, Cox et al. 2010). Thus, the design principles are suited to explain robustness, but not inequality (Oberlack et al. 2015). Some design principles can even reproduce inequality, if designed in the wrong manner. For example, if collective choice arrangements (principle 3) institutionalize gender inequality in leadership positions in CBOs over the long term, or if rules for the proportionality of costs and benefits (principle 2) imply that distribution of benefits is gender-biased due to gendered roles that imply greater engagement of men in cooperatives. Therefore, if research was to extend the design principles in ways that are not only robust but also just, then socially disaggregated assessments of the design principles are needed. Our results show that cooperatives’ strategies to enhance inclusion of women go clearly beyond the design principles, specifically communication, training and awareness raising as well as economic opportunities. Therefore, efforts to identify design principles for environmentally just community-based governance should not only socially disaggregate the existing eight design principles, but unpack the interconnected dynamics at multiple levels, such as cooperatives, household, individual and wider communities.

Third, the value chain perspective questions the traditional focus of commons research on natural resource management because environmental justice does not only depend on resource management – i.e. the upstream stage of a value chain (Villamayor-Tomas et al. 2015). Our results show how cooperatives influence (in-)equalities in distribution, participation and recognition by assuming roles in downstream activities of value chains such as processing, logistics, trade and marketing. However, the (institutionalized) terms of inclusion in value creation crucially influence inequalities from local to global scales (Ros-Tonen et al. 2019). Therefore, future research should critically reflect under which conditions value chain inclusion represent continued practices and legacies of colonialism (Quijano 2000), and under which conditions inclusive value chains may represent options of decolonized practices in line with environmental justice.

6.2. Indicators to assess environmental justice for women in community-based collective action

Conducting empirical environmental justice assessments is challenging, because its meaning differs according to persons, social-ecological contexts and places (Walker 2012). Consequently, there is no standard set of indicators of environmental justice (Boillat et al. 2018). Our mixed inductive-deductive methodological approach to assess environmental justice allowed us to identify frequent and significant themes that are relevant according to the diverse perspectives of our respondents (Yin 2013). Table 5 condenses these perspectives into a set of indicators. We hope this may be useful for analysts interested in conducting environmental justice assessment in similar contexts of community-based collective action and value chains. In addition, future research may further advance these indicators into a traffic light system that helps diagnose or benchmark levels of environmental justice in CBOs.

Table 5

Indicators to assess environmental justice for women in community-based collective action.

| INDICATOR | DEFINITION | MEASUREMENT SCALE |

|---|---|---|

| Cooperative level: female cooperative members | ||

| Female cooperative members | Share of women among official cooperative members | Share |

| Women in leadership positions (social) | Share of women in leadership positions in social structure of cooperative | Share |

| Meeting and training attendance | Attendance of women in cooperative meetings and trainings | Frequency and quality of attendance, gender-disaggregated share of attendants |

| Quality of participation | Active participation and ability to influence collective choices | Degree |

| Cooperative level: female employees | ||

| Female employees | Share of women among cooperative employees | Share |

| Areas of work | Gender-disaggregated activities | Types of activities |

| Women in leadership positions (corporate) | Share of women in leadership positions in corporate structure of cooperative | Share |

| Salary | Gender-disaggregated salary schemes | Numerical |

| Household level | ||

| Allocation of tasks within household | Gender-disaggregated allocation of household tasks | Types of activities |

| Distribution of income and benefits from cooperative | Degree of (in)equality in income and in benefits from cooperative services | Degree |

| Decision-making power | Degree of (in)equality in decision-making power in household | Degree |

| Recognition within household | Recognition of persons, roles, and activities | Qualitative |

| Individual level | ||

| Self-esteem | Belief in one’s capabilities and worth | Qualitative |

| Mobility, exposure and recognition beyond community | Ability to travel, face exposure to different contexts and gain external recognition | Qualitative |

| Wider community level | ||

| Gendered roles | Degree of consistency of gendered roles in cooperative vis-à-vis wider community | Degree |

| Communal programs | Degree of cooperative programs open or for the wider community | Degree |

| Economic opportunities | Extent of jobs or other economic opportunities offered by a cooperative within its (rural) context | Numerical, types |

We recommend that an indicator-based assessment of environmental justice should be linked with a process-oriented understanding of power dynamics within and beyond CBOs. Commons scholarship has recently proposed several conceptual approaches that can be useful in this regard. For example, Partelow and Manlosa (2023) recommend distinguishing between power over, with, to and within; Morrison et al. (2019) distinguish between power by design, pragmatic power and framing power. Haller (2019) proposes an approach to disentangle bargaining power, and Kashwan et al. (2019) propose an “power-in-institutions-matrix”. Each of these approaches highlights certain aspects of how power unfolds in community-based collective action. From an ethical position, power is always present, but morally neither ‘good’ nor ‘bad’ per se. A moral point of view of justice provides an ethically relevant compass for studies of power in CBOs.

7. Conclusion and outlook

This study has shown that cacao cooperatives, as a type of CBO, can tackle gender inequalities and improve environmental justice through more inclusive value chains. However, greater efforts are needed in future practice and science. At a practical level, accelerated learning and scaling up of successful experiences across CBOs is required, which depends on effective networks and resources for exchange, social learning and formalized training. In science, presently largely disparate scholarly communities can develop new insights by joining forces, enabling integrative perspectives on the complex origins of gender inequality in value chains. On the one hand, collective action research needs to move beyond its focus on robustness to pay greater attention to environmental justice issues (Barnett et al. 2020). The conceptualization of distributional, procedural and recognition justice as interdependent dimensions that are conditional on each other has been supported by the results of this research and proved to be a useful analytical lens for studying (in-)justices within CBOs. Environmental justice research, on the other hand, needs to expand its established focus on resistance movements and environmental distribution conflicts to incorporate successful collective action around environmental goods that prevents the emergence of oppression and conflict in the first place. Moreover, future research should advance design principles for community-based collective action by socially disaggregating them to account for environmental justice and power asymmetries; and ongoing efforts to understand interconnected dynamics at multiple levels, such as cooperatives, household, individual and wider communities, should be strengthened.

Additional File

The additional file for this article can be found as follows:

Notes

[5] Blare et al. 2020.

[6] Blare et al. 2020.

[7] Translated from Spanish. Original statement: “De manera general es el hombre y si él no puede, es la mujer.”

[9] The numbers are, however, not entirely comparable since not all cooperatives produce cacao derivatives, an activity typically only conducted by women. Additionally, not all of the cooperatives that do produce derivatives included the women working there in their count of regular employees.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge fruitful discussions and support by Abel Pezo Valles, Freddy Yovera, Miguel Angel Dita Rodriguez, and Rachel Atkinson as well as the 41 persons who participated as interviewees in the empirical part of this research. We also appreciate the helpful anonymous reviews.

Funding Information

Funding from the European Research Council (ERC, grant no. 949 852) and a travel grant from the Freunde der Universität Freiburg made this research possible.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.