Introduction

Irrigation communities have come under great pressure in many rural areas of the world (Cambaza et al., 2020; Sanchis-Ibor et al., 2017; Hoogesteger et al., 2023b). As prices for agricultural products and support for smallholders decrease, peasant farmers increasingly diversify their livelihood strategies (Coe and Hess, 2013). This threatens collective action and investments for the sustenance of collectively managed irrigation systems (Meinzen-Dick et al; 2022; Sanchis-Ibor et al., 2017). While research shows that many irrigation communities have proven to be very resilient and adapt to social, economic and technical transformations (Sese-Minguez et al., 2017; García-Mollá et al., 2020; Mirhanoğlu et al., 2023), there is little known about how relations of production and access to resources, especially land and water, shift among the commons as part of these processes. To fill this gap, in this research we look beyond the institutions for collective resource management and focus on understanding how, by whom and for whom farmer managed irrigation systems function; and how this functioning transforms as a result of broader processes of agrarian change. We do so by analyzing the transformation of production processes and related social relations among the commons of a smallholders managed groundwater irrigation system in the state of Guanajuato, Central Mexico.

Over the last four decades, in Latin America, as well as in other parts of the world, important neoliberally inspired transformations spurred agrarian change (Oliveira et al., 2021). The debt crisis and related structural adjustment programs that were implemented in the 1980s, marked a transition from a State developmentalism import-substituting-industrialization economic model to the neoliberal era that was inspired by the Washington consensus (Kuczynski and Williamson, 2003). These changes deeply transformed the rural economy and society, leading to what has been called the ‘peasant’ crisis (Kay, 2015). Neoliberal policies successfully boosted non-traditional, often elite controlled, agricultural exports — such as vegetables, fruits and flowers— while traditional export crops (coffee, cacao, sugar, bananas) and production for the domestic market grew at a much slower pace (Kay, 2008). In this process, transnational agro-industries, corporate capital and local elites have increasingly controlled agriculture and related access to land and water at the expense of smallholders (Hartman et al., 2022; Hoogesteger, 2018; Mena-Vasconcés et al., 2016).

The ‘peasant’ and related ‘rural crisis’ that resulted impacted institutions for the management of commonly held natural resources such as forests, pastures, land and also irrigation communities. Land and water reforms in many Latin American countries enabled the ‘legal’ privatization of communal lands (and related resources) and water. This facilitated and formalized the accumulation of access to land and water (mostly as irrigated land) by transnational agro-industries, corporate capital and local elites in Chile (Murray, 2006), Coastal Peru (Damonte, 2019), Ecuador (Mena-Vásconez et al., 2016) and Mexico (Ahlers, 2010) amongst others. Though these larger process of land and water accumulation have received quite some scholarly attention (Mehta et al., 2012; Franco and Borras, 2019), little research exists on how agrarian changed that was induced by neoliberal polices, the privatization of land and water tenure and the peasant and rural crisis have altered access to irrigation among smallholders and its consequences on the functioning of institutions for collective action. In this article, we contribute to this research gap by analyzing how in the ejido (Mexican communal land tenure system)1 Jesús María, in central Mexico agricultural production and access to groundwater irrigation have transformed since the mid-1990s. In doing so, the main research question that guides our inquiry is: how does agrarian change impact institutions and resource access in smallholder irrigation communities?

In the next section we theoretically elaborate on the relations between institutions for collective action, agrarian change and land & water accumulation. Thereafter we present the research methodology. Then we present the origins, development, importance and demise of the ejido system and smallholders support polices in Mexico. Section 5 presents the origins and development of groundwater irrigation in ejido Jesús María. In section 6 we analyze how agrarian change and the related rise of asparagus production led to the accumulation of access to irrigated land, changing the commoners base as well as the distribution of benefits and the institutions of the irrigation community. In the conclusions we reflect on this case and its significance for debates on agrarian change, irrigation communities and the commons.

Bringing agrarian change concerns into the study of institutions for collective action

For decades studies of user managed irrigation systems have been informed by the notions developed by Elinor Ostrom (Ostrom, 1990; 2007; 2009). Within this school of thought the Institutional Analysis and Development framework (IAD) provides one of the most widely applied approaches to investigate common-pool resource institutions and related governance (Van Laerhoven, Schoon & Villamayor-Thomas, 2020). This approach is useful for structuring inquiries into institutional development and sustainability across case studies. Its’ lines of inquiry focus on, amongst others, formal and informal rules, biophysical characteristics of resources and socio-economic and cultural attributes of the community of users that is involved in institutions and process of common-pool resource governance (idem). Critical institutionalism, which builds on the school of thought of IAD, incorporates attention to ways in which institutions interrelate with people’s everyday practices, and how these transform through dynamic processes of ‘institutional bricolage’ (Cleaver and de Koning, 2015; Faggin and Behagel, 2018; Whaley, 2018). Whaley (2018) highlights the need for a critical analysis of the ‘complex-embeddedness’ of institutions. Another element which needs attention is an analysis of the processes of transformation and change that take place within institutions; processes that as Heinmiller (2009) points out are bound to ‘path dependency’.

Irrigation communities and their transformation

Focusing especially on irrigation communities, different authors have looked at processes of institutional transformation. Pérez et al. (2011), highlight the importance of local users’ knowledge in efficiently responding to external threats and internal transformations. In analyzing the interactions between institutions and technology, van der Kooij et al. (2015), show how institutions are transformed through interactions between users, institutions and infrastructure through time. In this line of research a lot of insights have been generated in relation to how the introduction of drip irrigation changes different elements of irrigation communities (Benouniche et al., 2014; Sanchis-Ibor et al., 2017; Venot et al., 2017; Hoogesteger et al., 2023b). These transformations take place through contested processes of adaptation in which all three dimensions change interactively through what Mirhanglou et al., (2023) have termed socio-material bricolage.

Another point of attention has been how, under different processes of transformation, norms and rules change in institutions. Thapa and Scott (2019) show how in Nepal, under conditions of water stress, irrigation communities adopted infrastructural and operational measures that allowed the irrigation communities to sustain both institutions, systems and production. They highlight the importance of the sustained interest of users to solve problems collectively and point out that leadership, transparency and the mobilization of labor are key elements for this. Cody (2019) points us at the importance of internalized norms of cooperation as norms evolve to sustain irrigation systems; even as these norms are externally imposed. Such impositions often lead to: a) conflicts and negotiations both internally as well as in relation to external actors (Hoogesteger, 2013; 2015); and b) to the evolution of norms resulting in new ‘hybrids’ that integrate elements of both existing and newly introduced normative frameworks (Boelens and Vos, 2014).

Meinzen-Dick et al., (2022) in their study on irrigation communities in Nepal, point out how roles and responsibilities can change within institutions. They show how women have taken up more and different roles in the irrigation communities and agricultural production due to increased rural men out migration. A process that greatly hinges on the sustenance and development of social capital as members navigate institutional transformations and manage external relation and support (Chai et al., 2018). Building on this scholarship and insights Hoogesteger et al., (2023a) have pointed at the importance of community, individual & collective action and developing political agency to amass external support as key pillars that support the sustenance of irrigation communities.

While these studies foreground the interactions between technology, water flows, norms and gender relations within the institutions, they tend to take agricultural production as a given background. This despite the fact that sustaining crop production is a central pillar for irrigation communities and their sustenance. Thapa and Scott (2019) for instance point out that in many irrigation systems users have changed to the production of fruit trees instead of paddy and wheat as the former require less water and labor. In the next section we elaborate on how these changes in production fit in the broader context of institutions for collective action, rural transformations and agrarian change.

Incorporating agrarian change in the study of the commons

We propose to borrow insights from the field of inquiry of agrarian studies which has focused on understanding the peasantry, social relations of production and related processes of social differentiation, amongst others (Akram-Lodhi and Kay, 2010; van der Ploeg, 2014). Studies on peasant differentiation have identified differentiation processes based on unequal access to (irrigated) land; the degree of market involvement by families; and the ability to incorporate the work of family members in the production unit versus proletarianization (Bernstein, 2010). If we translate these concerns to the study of institutions for collective action and its’ relation to agrarian change, we propose that the four questions posed by Bernstein (2010) namely: “Who owns what? Who does what? Who gets what? What do they do with it?” (p. 22) can well be applied to understand the transformations in institutions for collective action. These questions are especially interesting in terms of how the answers change through time and triggered by what social, infrastructural or natural factors.

The notion of ‘resource access’, which Ribot and Peluso (2003) define as ‘the ability to benefit from things’ (p. 153), stands central when answering the above questions. It allows for a more precise analysis of the processes of land and water accumulation in and amongst smallholders (commons).

In answering the above questions through the notion of ‘access’, it is essential to recognize that smallholders’ households, the management of commons (land, water, forests, etc.), and rural communities are highly dynamic and integrated into regional, national and transnational politics and economies. This integration takes place mostly through the insertion of household members in diverse labor markets, trade and cyclical or permanent migration (and related remittances), as well as through the sale of production to these broader markets (see for instance Gray, 2009). This contributes to an intensification of the relations between the local and the global and between the urban and rural worlds and related agrarian transitions. The latter are marked by the diversification of livelihood strategies, lifestyles and smallholders economies (Kelly, 2011; Robson et al., 2018).

In this context labor migration (permanent and circular) and remittances play a crucial role in smallholders livelihoods around the world. Migration dynamics facilitate and steer processes of both ‘peasant deactivation’ and ‘repeasantization” and related access to natural resources (Sunam and McCarthy, 2016). The result is that migration has come to play a central role in reorganizing social structures and access to productive resources in rural areas (Hoogesteger and Rivara, 2021). These changes have impacts on the mobilization and organization of labor (within households and within communities); access to (natural) resources; and institutions for collective action (Klooster, 2013).

Therefore, Hall et al., (2015) point to the need to study and analyze ongoing trajectories of agrarian change and rural transformations; especially in how these relate to processes of land and water accumulation (see also Mehta et al., 2012; Franco and Borras, 2019). We enrich this debate by looking specifically at how in a context of neoliberal reforms, agrarian change brings about shifts in access to land and water among the commons affecting how, by whom and for whom common resources are used; and how this affects local institutions for collective action. It also allows to focus on the inequalities in natural resource access that are generated by these processes of transformation of the commons and the social-material fabric that sustains their institutions (in this case specifically related to irrigation communities). This focus adds a new line of inquiry to the 4 questions posed by Berenstein 2010 (see above) by expanding it with the following question: How are changes in the above four questions mediated through the transformation of institutions for natural resource management through collective action?

Methodology

This research is part of the broader research efforts of the first author in the state of Guanajuato. As part of the broader study and in working with different stakeholders related to groundwater governance in the area, the ejido Jesus María was identified as an interesting case to analyze because it is one of the few ejidos in the region that has successfully transitioned to the production of agro-export crops, created a cooperative and maintained collective irrigation management.2 First contacts to get access to the ejido were acquired through the user based Groundwater Management Council (see Wester et al., 2011) of the area. After getting initial access to the people in the ejido, the data on the case study was collected through a mixed methods approach aimed at understanding the commons and how these transform (Meinzen-Dick et al., 2004). The bulk of the primary data was collected by the second author in four-months (July – November 2017) of fieldwork in the ejido Jesús Maria. Anthropological research methods were used to understand day-to-day practices and relations related to the production of asparagus, the workings of the asparagus producing cooperative, and the functioning of the irrigation community. For the latter field observations were made during the irrigation turns, related practices and interactions; attendance to meetings of the production cooperative and the irrigation community; participant observation of day-to-day activities related to the production of asparagus in the field, harvesting and marketing. To better place these activities in the context of community life and to develop trust and social relations in the broader community social gatherings and local festivities were also attended. These observations were supplemented by twenty semi-structured interviews that were held with the main actors behind the rise and expansion of asparagus production in the ejido. These interviewees were approached using a focused snowball sampling methodology. Through this purposive snowball sampling methodology relevant informants were identified with and through earlier informants. The identification of new informants was based on the topics of which we wanted to gather more data and/or with whom we wanted to corroborate data from earlier interviews. As most interviews were purposive in the sense that people were identified based on their position and knowledge, the semi-structured interviews focused on specific themes that people were knowledgeable of. As a result the interviews were guided by the previously identified themes to be talked about. These were discussed with the interviewees through open semi-structured conversations.

Data was stored in field notes. We did not audio-tape the interviews due to the suspicion many people showed towards the researchers. Triangulation between the different respondents and observations made was used to corroborate responses and findings. For the latter some key players were interviewed three to four times to fill gaps. This was done during follow-up interviews and field visits of two weeks in 2018 and 2020. The semi-structured interviews were used to inductively and with the support of field notes reconstruct the history of the ejido, its’ agricultural development and especially groundwater irrigation and its’ management. The observations helped to contextualize and place the data from the interviews in their current context. In this contribution all respondents’ names have been anonymized by using fictitious names. Another part of the research which analyzes livelihood strategies based on a survey carried out with 58 smallholders in the ejido has been published in Hoogesteger and Rivara (2021).

The rise and demise of land and water commons in Mexico (1917–1992)

In the centuries that followed the Spanish colonization of Mexico, communal property became the object of various enclosures that led to different forms of appropriation by Spanish and mestizo colonizers (Wolfe, 2017). This land (and implicitly water and other resources) accumulation and widespread poverty and oppression of the rural population fueled the Mexican Revolution that shook the country between 1910 and 1917. In 1910, at the wake of the revolution, 0.2% of the landowners owned 87% of rural land (Assies, 2008). Therefore, one of the most important demands of various revolutionary factions was ‘land to the tiller’ as well as a historical restitution of lost village and community lands (Nuijten, 2003).

Article 27 of the 1917 Constitution established that land and water resources belong to the nation settling a legal framework for the creation of an ‘agrarian social sector’ alongside private property. Through Article 27, the Mexican government got the legal faculties to transmit land and water from private parties (large private property owners) to communities. Large estates were expropriated and subsequently divided up and redistributed to villages, communities and rural settlements that requested land and water access (Assies, 2008 p. 40). This was granted by the state mostly in the legal form of ejidos. Members of an ejido were denominated ejidatarios and held ‘private’ land use rights on certain agricultural plots, while also having the right to use shared common lands (mostly grazing lands and forests). Ejido land was legally inalienable. Ejidatarios had (use) usufruct rights. By the mid-1990s about half of the Mexican arable land was in the hands of around 28,0000 ejidos (Key et al. 1998).

Beside land distribution, since the mid-1930’s, the government created a full agrarian support system geared towards making the smallholders sector -and especially that represented by the ejido- productive (Wolfe, 2017). It consisted of subsidies (in kind and in cash), loans, technical advice and improved technologies such as seeds and improved livestock, amongst others. As a result land distribution through the ejido, coupled to special programs and subsidies became a system of permanent support to peasant communities (Albertus et al., 2016).

In the 1980s, cuts in social expenditure greatly affected the smallholder sector that had become dependent on state support for sustaining production of basic grains. In 1986, Mexico signed the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and in 1992, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) between Mexico, Canada and the U.S.A.. These agreements facilitated the increase in commercial flows between the three countries by reducing trade barriers but also demanded liberalization of Mexico’s economy by, amongst others, severely reducing support to smallholders that had until then produced mainly basic grains with state support. Between 1994 and the mid-2000s, corn and wheat imports from the U.S.A. increased 240% and 182% respectively (Wilder and Whiteford, 2006) as internal production declined because many ejidatarios stopped producing basic grains (Appendini, 2014; Navarro-Olmedo et al., 2016).

According to Weisbrot et al., (2017), approximately 4.9 million family farmers were forced to move from a peasant to a proletarian based livelihood. According to estimates, 3 million became seasonal or permanent laborers in the expanding agro-export industry (Weisbrot et al. 2017). Due to widespread poverty, which concentrated mostly in the rural areas, migration to the U.S.A. increased 79% between 1994 and 2000 and remittances flows from north to south rose from 3.7$ billion in 1995 to 23$ billion by 2006 (Fox and Bada, 2008). These processes, in which smallholders left their land and production, were facilitated by the privatization of the land and water tenure systems.

In 1992, constitutional modifications reconfigured the ejido land tenure system. The reform formalized the notion that the ejido was inefficient (Robles Berlanga, 2012). A modification of Article 27 facilitated the privatization and dissolution of ejidos (see Assies, 2008). In parallel the National Water Law and its regulations (1994) separated land tenure from water tenure through the introduction of private concession titles (rights) (LAN, 1992). Rights are granted through the National Water Authority (CONAGUA) and registered in the national Public Registry of Water Rights (REPDA) (Hoogesteger and Wester, 2017). Since 2001, water rights transmissions are legally allowed amongst users and to newcomers within the same hydrological units (aquifer or watershed) (CONAGUA, 2012).

The agro-export boom in Guanajuato

Guanajuato is one of Mexico’s most important groundwater dependent production and export areas of fresh, canned and frozen fruits and vegetables (Hartman et al., 2021). Many medium and large commercial farmers that operate as family businesses have greatly benefitted from the production of fresh vegetables that are sourced to larger (inter)national agro-export companies; mostly through contract farming arrangements. This agro-export sector has greatly benefitted from neoliberal policies, the liberalization of trade and state subsidies aimed at increasing the international competitiveness of agro-export agriculture in the state. However in the same state, a large portion of the smallholders sector (ejido) is by and large in crisis due to the low profitability of traditional crops and little governmental support to shift to more capital intensive crops. Added to these challenges, sustained aquifer drawdown has increased groundwater pumping costs and/or dried wells (Hoogesteger and Wester, 2017). As a result many ejidatarios have been driven out of production since the mid-1990s. This has increased rural outmigration and much labor has been absorbed through international migration to the USA, as well as by large commercial producers, agribusinesses and industry in the region. In this context, many smallholders have sold or rented out their land and groundwater concessions to commercial farmers. One of the few ejidos of northern Guanajuato in which many producers have shifted to non-traditional agro-export crops is Jesús María. In it, smallholders have switched from traditional crops to the production of asparagus. Therefore this case offers a valuable lens to analyze how in the broader national policy context and within the specificities of the state of Guanajuato, irrigation communities are sustained and transformed through and with changing patterns of access to irrigated land in and among smallholders in a context of a productive transition towards a non-traditional export crop.

The Rise and Fall of Irrigated Agriculture in the Ejido Jesús María (1950–2000s)

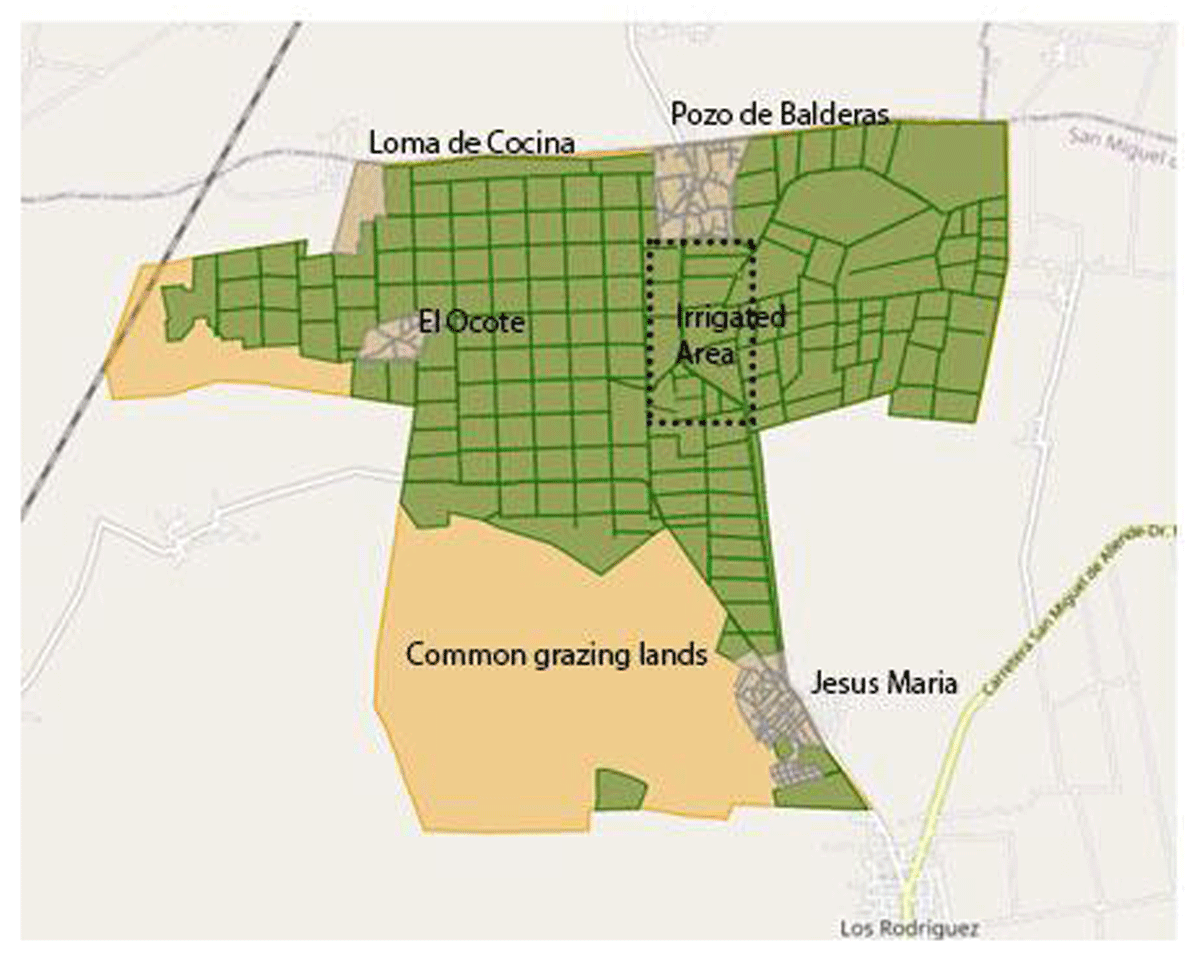

The ejido Jesús María, located in the North-East of Guanajuato, reflects the Mexican 20th century agrarian transformations in a nutshell (see Table 1). Hacienda workers organized as ejido after a clash between the landless laborer’s of the hacienda and the owners in 1939. The land was occupied soon thereafter and in 1955, after long legal procedures, the ejido Jesús María was legally constituted. It consists of four communities (Pozo de Balderas, Loma de Cocina, Jesús María and El Ocote) whose ejidatarios collectively own 3,187 hectares (ha) (PHINA, 2020) (see Figure 1). Of this area 2,050 ha are individually parceled, 968 ha are designated for common use, and 168 are designated as human settlements. Presently it is owned by a collective formed by 162 ejidatarios and 53 posesionarios (possessors of land, who are not official members and thus have no vote, in the ejido assembly). According to official data, 325 households live within its’ boundaries, the majority of which reside in the communities of Jesús María and Pozo de Balderas (PHINA, 2020). In practice the number of inhabitants in the ejido is dynamic as a large portion of the population (estimates of locals run up to 50%) is engaged in temporal or permanent labor migration to the U.S.A.

Table 1

Summary of most important periods and moments of the Mexican Land Reform era (1910–2000s) (own elaboration).

| YEAR | EVENT |

|---|---|

| 1910–1917 | Mexican Revolution with as one of the main demands ‘land to the tiller’. |

| 1917–1992 | Mexican Land Reform distributing half of Mexican arable land to over 28,000 ejidos (communal lands that were inalienable). |

| 1930s–1970s | Agrarian support system aimed at making smallholders agriculturally productive and competitive in the market |

| 1980s onwards | Neoliberal reforms and a gradual reduction in support to smallholders leading to stallholder bankruptcy, increased rural migration and proletarianization. |

| 1992 | End or Mexican Land Reform and amendments to Mexican constitution allowing the privatization of ejidos. |

| 1994 | Water reforms and the establishment of private water concessions that separated land and water ownership. |

| 2001 | Provisions in the water law that made water rights tradable. |

Figure 1

The ejido Jesús María with its communities, parcels and the irrigated area (own elaboration based on PHINA, 2020).

Initially, beside the communal grazing lands -which compromised the largest portion of the ejido- 125 ejidatarios received 11 hectares of arable land. At that time, production was rain fed and consisted primarily of the combined cultivation of maize, beans, and squash. Between the 1960s and 1970s, the government financed land clearing to facilitate agriculture. This led to a second individual parcel distribution that gave ejidatarios an additional four hectares which many ceded to relatives.

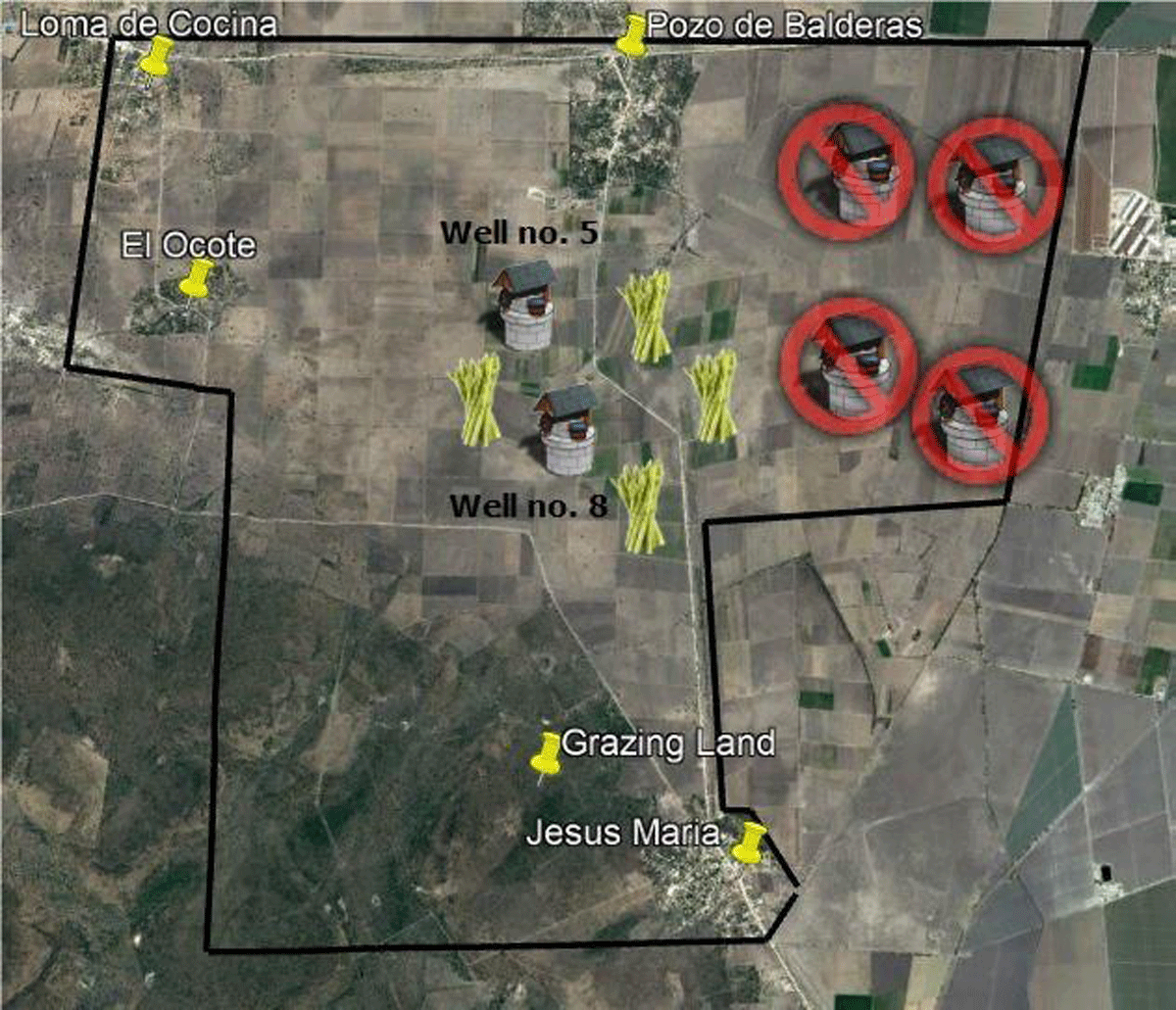

The Plan Nacional de Obras de Pequeña Irrigación (National Plan of Small Irrigation Works), financed four wells for irrigation with groundwater in the ejido between the late 1970s and early 1980s. This enabled the beneficiary smallholders to boost production through irrigation. To manage and operate the well and irrigation network, four water users groups (of around 15 users each) were created. Each group appointed a well manager (pocero) and established its own system of water turns. Most new irrigators, started to grow 1–2 hectares of alfalfa year round, providing a steady cash flow (8–10 harvest moments in a year). Beside alfalfa, most irrigated a part of their traditional staple crops in the spring-summer cycle. This productive transformation was facilitated by convenient loans -from the state owned National Rural Bank- to buy seeds, tractors and other required inputs. Two additional wells – numbered 5 and 8 – were dug in the late 1980s.

Due to declining aquifer levels two wells dried up towards the end of the 1980s and were never deepened or replaced. By 1997, two more wells had dried up (see Figure 2). According to anecdotal stories of the interviewed, this fell together with increased migration from the ejido to the U.S.A.,3 especially among the youth that saw no future in agriculture. This directly related to the high costs of groundwater pumping for irrigation system sustenance and the very low returns that smallholders were getting from production. It resulted in decapitalized smallholders that could not invest in well repositioning and that opted to migrate and/or become semi-proletarians. With the exception of the producers with land that could be irrigated from wells 5 and 8, most other ejidatarios reverted to the production of rain fed corn, beans, squash, sheep, goats and cattle rearing (mostly for subsistence), while often poorly paid non-farm incomes, and remittances, from family members living and working in the U.S.A., became increasingly important in rural livelihoods (Hoogesteger and Massink, 2021; Hoogesteger and Rivara, 2021).

Figure 2

Ejido Jesus María and position of well in the ejido (source Hoogesteger and Rivara, 2021).

Through the national land titling program that was put in place after the 1992 reforms, the ejido and the individual plots within it were measured and registered in the National Agrarian Registry (RAN) in 1998. The ejido lands, both the communal grazing lands as well as the private plots, have remained ejido as the general assembly has never approved a switch of the ejido into a private property regime also called dominio pleno.4 However important land transactions have taken place in the ejido since the mid-1990s as evidenced by the 53 (external) posesionarios that have bought land in the ejido (PHINA, 2020).

Accumulation of Access to Irrigated Land in the Ejido

Who owns and who gets what? Changing access to land and water

In the late 1990s, when many producers were going through dire times, and enabled by the new legislation, land transactions started to occur in the ejido. As put by one producer:

“In the past [in the 1970s 1980s], in some years farmers did not need to work the full plots, we could make a living out of fewer hectares. Later on, lower yields, lower prices, variable rains and the need of findings better market options implied the necessity to work more land, mostly for self-consumption”.

This situation led some households to sale their irrigated parcels that did not generate enough profits, as put by a community member that no longer owns irrigated land:

“I wanted to sell, I could not afford the electricity costs of the well.”

Miguel from an adjacent community bought a few irrigated hectares in the central part of the ejido, becoming a posesionario. He had capitalized as a migrant laborer in the USA and worked for large farmers producing asparagus in the area. Miguel partnered with two ejidatarios (Jose and Antonio) (that had the capital to invest, due to remittances from family working in the USA) and started producing asparagus, which in the climatological conditions of the area is only possible with irrigation. The upfront investments to produce asparagus are high compared to other crops because of the high costs of plant material and the fact that to establish the crop a period of 1.5–2 years -in which the crop develops before the first harvest is possible- has to be bridged. Once the crop is established it has a productive life of between 7 to 9 years during which the produce is harvested on an annual basis between June and September. To bridge the initial two years of investments without harvest, many ejidatarios used capital from remittances or loans from fellow ejidatarios.

To organize production and commercialization producers in the irrigation community created a cooperative. It was led by Miguel and Jose. Initially Jose and Antonio started with 1–2 hectares, but within a few years expanded their production to fields on which they had previously produced alfalfa. In 2005, two alfalfa growers joined the cooperative. This was done through a sharecropping deal with Miguel and the technical support of Jose. This deal enabled the newcomers to make the investment costs through a loan, while sharing part of the profits with Miguel. Lured by the profitability of the crop and facilitated by the know-how and support from Jose and the cooperative, in the years that followed several other ejidatarios joined in the same scheme. At the same time, external petty investors (just as Miguel) bought land, became posesionarios and started to produce asparagus (with the technical support of Jose) and joined the cooperative. Though organized in a cooperative for the commercialization of the asparagus, production and in some cases also the harvest is arranged individually.

By 2013, the cooperative had 13 producers and two shareholders that did not own land but had co-invested with ejidatarios. Three producers were posesionarios (external to the community) who bought irrigated land in the ejido. Five ejidatarios that started asparagus production, had worked for extended periods of time as wage laborers in the USA. Currently a significant amount of irrigated land is not tilled by the owners, but by sharecroppers (see Table 2) in a broader context of diversified livelihood strategies that include irrigated agriculture, rainfed agriculture, animal husbandry, wage labor outside of the household and in some cases remittances (see Hoogesteger and Rivara, 2021 for a detailed analysis of the livelihood strategies and related processes of social differentiation in this ejido).

Table 2

Producers’ expansion of asparagus production.

| PRODUCER | STATUS IN EJIDO | START ASPARAGUS PROD. | INITIAL ASPARAGUS PRODUCTION (HA) | ASPARAGUS PRODUCTION 2018 (HA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Miguel (Posesionario) | 1998 | 2 | 28 |

| 2 | Antonio (Ejidatario) | 1998 | 1.5 | 20 |

| 3 | Jose (son of Antonio) Ejidatario | 1998 | 1 | 13 |

| 4 | Posesionario | 2005 | 2 | 2 |

| 5 | Ejidatario | 2005 | 2 | 4.5 |

| 6 | Posesionaria | 2007 | 3.5 | 6.5 |

| 7 | Posesionario | 2008 | Unknown | 8 |

| 8 | Son of ejidatario | 2009 | 2 | 6 |

| 9 | Ejidatario | 2010 | 2 | 3.5 (2 with a partner) |

| 10 | Ejidatario | 2011 | 2 | 3 |

| 11 | Ejidatario | 2011 | 1 | 4 (2 with a partner) |

| 12 | Ejidatario | 2011 | 1 | 6 |

| 13 | Ejidatario | 2011 | 1 | 1.5 |

| Total | 22 | 99 |

Two kinds of agreements are dominant: sharecropping or land rent. In sharecropping the most common arrangement is that the sharecropper of the land makes the upfront investment of planting and takes care of the crop (and all required inputs) throughout the year (in many cases Jose is hired to do this because of his know-how and because he owns the required machinery). The owner of the land puts his land and water right in and takes the responsibility of arranging the necessary labor for the harvest. The revenues from production are then split 60%-40% or 50%–50% between the tiller and the owner of the land. Such agreements usually run for the length of the productive life of an asparagus crop (8–10 years).

When land is rented out, the land owner receives a fixed annual payment for his/her land and water. The agreements usually run for 8–10 years. In 2020, the fixed rent per hectare was between 4000–6000 pesos (250–400 US Dollars) and often the first year when the producer can’t harvest the rent is only half. As summarized in Table 2, this growth in the surface cultivated with asparagus has gone hand in hand with a local accumulation of access to irrigated land. Miguel, Jose and Antonio now control more than half of the asparagus production in the ejido, they run the cooperative and manage the groundwater pump, the irrigation turns and the collection of users fees to pay for the operation of the groundwater pump. They have gradually expanded production on the irrigated lands of other ejidatarios that willingly sold, rented or sharecropped these out. Additionally Jose plays an important role in the production process of almost all producers (see next section). By 2020, the whole irrigated area with the exception of one user that was producing alfalfa had been transformed to asparagus. The expansion in the last three years (2017–2020) had taken place exclusively through arrangements of sharecropping by producers’ (newcomers to the asparagus cooperative) own investments. As the revenues from asparagus production rendered irrigated agriculture profitable again the rent and sale of irrigated land stalled.

Who does what in production? The organization of production

The production of asparagus is managed and controlled through the producers cooperative. Miguel, Jose and Antonio run the cooperative and provide technical support, advice and sometimes credit to newcomers (often through sharecropping arrangements). As put by Jose: “I bring the know-how, some equipment, input and financial capital if necessary so that we can take advantage from the market conditions [for asparagus] and water resources”.

They own and rent and operate the needed machinery, acquire the required inputs (plants, fertilizers and pesticides) in bulk, supervise the harvest and the products’ quality, arrange transport of the harvest to the agro-export company that buys the asparagus, do the cooperative’s administration and bookkeeping, and organize and chair the cooperative’s group meetings. In some cases they organize the labor needed for harvesting for producers that want this. Miguel and Jose negotiate and establish contracts with the buying agro-export company every year and arrange all financial matters including paying out the incomes to each producer. In this way, the organization of production in the irrigated fields of the ejido as well as the marketing of the crops has concentrated in the hands of a few. As stressed by Jose: “Do not forget that, yes, we are an association. But an association of individuals who come together to sell the product and buy some inputs but not to share other practices”.

The family house of Jose and Antonio, is the heart of the cooperative and the place where all the meetings are held, where the machinery is kept, where the inputs are stored and distributed from, where the payments are made, and the place where the asparagus harvest is brought together for transport in the months of June, July and August. In these months the weekly revenues from production are paid to the producers. When applicable, the input and labor expenditures made in advance by those that control most of the production process are deducted from this payment. At the end of the harvesting season, the company makes a final payment to the cooperative, based on the real daily market prices of that season. This final payment is distributed to each producer proportional to production somewhere in September. This moment marks the end of the harvesting season. When this final payment is made the yearly accounts are settled and the bookkeeping is closed.

Of the producers of the cooperative, only two work the land and do the harvesting with family labor. All other producers invest part of their own time in management and supervision, but the bulk of the manual labor in the field is done by hired laborers from other families in the ejido and the surrounding villages (see Table 2).5 In the peak harvesting season (June–July), about 100 workers harvest the asparagus spears. Most work under the supervision of producers Jose and Antonio, who coordinate the harvest of the majority of the fields (as arranged with the producers).

Who does what in the institution for collective action? Irrigation management

The management and distribution of irrigation water has concentrated in the hands of Antonio and Jose. Jose is the responsible for managing the wells. Based on his knowledge of the system and his central power position within it, he decides when the wells are put to work depending on the irrigation needs of the crops of the different users. He is the one that guides the irrigation water through the piped network and arranges the irrigation turns. He is also responsible for collecting the fees to pay for repairs that the well or the network require. In 2020, Jose managed to get subsidies from the state government to support the installation of drip irrigation in all fields. As manager he is the one that understands the newly installed technology and how it works. The latter has enabled more efficient irrigation on the fields. The water that was ‘saved’ has been used to expand the irrigation network and include new users and fields in the production of asparagus. Though during the interviews some users complained that the fields of Miguel, Jose and Antonio get preferential water turns, most interviewed users expressed that they got their irrigation turns when needed. For operation and management of the two wells and related irrigation system Jose has gained the users’ trust based on his knowledge, on how he manages the system on a daily basis, for the transparency in management, on how he ensures that every water user gets his water turns; and on his ability to mobilize external support for the technical sustenance and transformation of the system. For larger decisions such as the installation of drip irrigation, the need for investments and the expansion of the system Jose consults the general assembly of users who takes these decisions. Through the latter knowledge, transparency and the willingness of users to sustain their system have enabled the users to mediate the institutional transformations needed to sustain the system.

One of the largest concerns of most users in relation to water are the declining aquifer levels (see for instance (Knappett et al., 2018; Knappett et al., 2022). These affect the yield of the wells, especially in the driest period (May-June) when also the irrigation demands are the highest. The falling water tables also raise important concerns about the costs that might be needed in the future to deepen and/or reposition the wells and the larger socio-ecological system. However, the users feel that this issue is an issue which is out of the reach of their actions as the larger aquifer problem is seen as a classical common resource pool problem (see Hoogesteger, 2022).

Conclusions: Commons, Agrarian Change and Accumulation

In this article we explored a different entry point to understand the transformation of the commons through the case study of an irrigation community. Building on notions of institutional analysis and agrarian studies we show how agrarian change interlocks with transformations in resource access and institutions for collective action. We propose that these can be studied by answering the following questions within institutions for collective action: Who owns what? Who does what? Who gets what? What do they do with it? How are changes in the above four questions mediated through the transformation of institutions?

This focus highlights first of all the importance of understanding the impact of broader agrarian policy transformations on rural economies, production and related livelihood strategies of smallholders (irrigators). Secondly, it focuses the attention on processes of change, which implicitly frames the commons, communities and their institutions for natural resources management as dynamic. This implies that the commons and their institutions cannot be understood as ‘fixed’ but as entities that are in a constant process of transformation within their broader socio-environmental context. Finally, it focuses the attention on processes of transformations in access to productive resources (in this case land & water) and agricultural production. The latter concentrates on better understanding how livelihood strategies change and the triggers and mechanisms through which access to productive resources shifts, and, in this case, accumulates in the hands of a narrower user base. A deeper understanding of the three abovementioned elements namely: a) broader agrarian policy and socio-economic context, b) livelihoods and related access to productive resources and c) related institutional transformations, offers -we contend- new and important insights into why, how and for whom institutions for collective action function, and why, how and through which factors and actors these institutions transform through time.

When applying the above presented analytical lens to the study of the ejido Jesús María in Central Mexico it brings the following to the fore. As in many other parts of the world, the smallholder sector, which is compromised mostly by the ‘ejido’ in Mexico, has been put under great pressure by globalization and neoliberal policies. As a result rural Mexico changed rapidly since the 1990s, transforming livelihoods by increasing the dependence on labour, migration and related remittances. The case of Jesús María shows how this changing, neoliberally inspired, socio-economic context put the management of the collectively owned and managed groundwater irrigation systems under great stress. It led to the abandonment of several wells. The two collectively managed wells that ‘survived’ are wells in which, with external capital, a transition to the production of asparagus as a non-traditional export crop took place. This transition went hand in hand with changes in access to irrigated land among ejidatarios and the incorporation of ‘outsiders’.

Today the production and commercialization of irrigated asparagus and with it access to productive resources greatly hinges on the technical expertise, networks and sometimes financial loans of three producers that have also sustained and mediated the needed institutional transformations. The latter have accumulated access to irrigated agriculture over the past two decades through different mechanisms that include buying new irrigated land, renting irrigated land on long-term (5-10 years) contracts, and through share-cropping arrangements with other producers. This has gone hand in hand with a concentration of the means of production and the management of the institutions for irrigation management. Though irrigation has been sustained, it is a system that functions very differently (production, commoners, institutions) than in the late 1990s.

Our study of this small irrigation community is based on qualitative research methods. The purposive snowball sampling methodology used allowed us to identify and interview informants that are all already connected and part of a network. This allowed us to better understand this network from the inside but also left omissions and possible contradictions that exist in the broader community out. The inductive interpretative approach used by the authors also brings with it personal biases, omissions and interpretations of the analyzed reality. In spite of the above mentioned biases and possible omissions, this case study shows the insights that can be brought to the fore when combining the study of the commons with insights and concerns of agrarian studies. We believe that there is much theoretical potential in the cross pollination of these fields of inquiry. Here we made and developed a first opening, but believe that there is much ground for further explorations that combine insights and questions from these two fields of inquiry.

Notes

[2] As analyzed in Hoogesteger, 2018 and in Hoogesteger, 2023 there are many ejidos in this region in which smallholder irrigation communities have fallen apart. This has led to land abandonment or the sale/rent of the land and water titles to large commercial producers.

[3] Family networks in some cities in Texas and especially in Salt Late City, Utah, have enabled and spurred the increased migratory flows out of the ejido.

Acknowledgements

We are very thankful for the valuable constructive comments and detailed suggestions of three anonymous reviewers.

Funding Information

This research was financially supported by The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO), grant no. W01.70.100.007. The research design, execution and publication is the initiative and responsibility of the authors. The usual disclaimers apply.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.