1. Introduction

Conditions for successful governance of common-pool resources (CPRs), such as irrigation, forest, and fishery systems, have received much academic attention since the 1980s (Baland & Platteau, 1996; Ostrom, 1990; Wade, 1988). Institutional dynamics and self-governance regimes, signified in seminal work by Ostrom (1990) on institutional design principles (DPs) and the Institutional Analysis and Development framework, have been mainstreamed in a large volume of literature on CPR governance (Agrawal & Yadama, 1997; Cox et al., 2010; Ostrom, 1992; Ostrom & Gardner, 1993; Tang, 1991).

Although scholars have identified many institutional and social-ecological variables related to the performance of CPR governance through rigorous empirical studies (Agrawal, 2001; Agrawal & Benson, 2011; Pagdee et al., 2006), the findings on conditions for successful performance are challenged by the complexity of CPRs as well as the diversity of local contexts. Empirical evidence suggests that simple linear and reductionist dynamics of single variables may misrepresent how a complex CPR system works (Levin et al., 2013). Moreover, the diagnostic approach often adopted by institutional scholars may overestimate the possibility of finding normative institutional solutions to reach desirable outcomes and oversimplify the combinations of different conditions in complex CPRs, especially between institutions and the contexts in which they operate. In other words, it is an extremely costly task to exhaust all the combinations of multiple conditions under which CPRs are governed sustainably (Agrawal, 2001). Overreliance on the diagnostic approach may result in falling into the “panacea trap” with romanticized imaginations of the real-world complexity (Anderies et al., 2007; Ostrom, 2007).

Institutional variables per se are insufficient to explain specific CPR governance performance and the effects of institutional configurations such as DPs cannot be isolated from local contexts (Araral, 2014; Baggio et al., 2016). Scholars have emphasized the significance of the interactions between institutions and local contexts. For instance, the congruence between appropriation and provision rules and the attributes of resource systems is one of Ostrom’s (1990) DPs. Young (2002) argued that the capacity and effectiveness of institutional arrangements to solve problems are relied on the degree to which they fit with the biophysical contexts of the CPR systems. It is thus reasonable to argue that complex interactions among variables of different dimensions account for most of the governance performance of CPRs (Partelow, 2018). Following this line of inquiry, Baggio et al. (2016) reviewed the configuration of DPs embedded in three types of CPR systems, namely irrigation, fisheries, and forest systems. This attempts to investigate the context by examining the effects of DPs in CPR systems with different biophysical traits (e.g., natural infrastructure mobility and hard, man-made infrastructure intensity). However, this attempt cannot capture the specific contextual variables that change significantly across the type and scale of a specific CPR system. For instance, groundwater and surface water irrigation systems may involve different institutions and organizations. These institutions and organizations are also subject to the different and broader political frameworks and cultural backgrounds in which the irrigation system is located. Likewise, apparent patterns and conclusions at one scale of analysis may not hold at other wider or smaller scales of analysis (Gibson et al., 2000). From this point of view, the simple combination of factors for CPR governance remains a major gap that obscures the in-depth understanding of complex CPR systems (Ostrom et al., 2007). Therefore, it is necessary to probe the effects of specific institutions combining with local contextual settings in order to discuss the performance of CPR governance (Araral, 2009).

This paper is motivated by the tension between contextual complexity and institutional performance along with the question of combination between institutional arrangements and their embedded social-ecological contexts in a specific type of CPR system. This paper focuses on the community-based irrigation system, which is well conceptualized as a traditional small-scale CPR embedded in broader political, institutional, social, and ecological settings (Hoogesteger, 2015; Pérez et al., 2011).

Community-based irrigation governance has been intensively studied in the past three decades during which time a global trend in devolution has enabled power transfer from the state to local users in the irrigation sector. Reform programs1 such as Irrigation Management Transfer (IMT) and Participatory Irrigation Management (PIM) and local self-governing organizations such as Water User Associations (WUAs) are often examined in the literature on community-based irrigation governance (Kadirbeyoglu & Özertan, 2015; Meinzen-Dick, 2007; Meinzen-Dick et al., 2002; Nagrah et al., 2016). As more scholarly work has emphasized the role of local communities in the success of irrigation management (Agrawal & Gibson, 1999; Bardhan, 2000; Sarker & Itoh, 2003; Wade, 1988) and has directed the use of methodologies to focusing on local water users (e.g., individuals, households, and communities) (Agrawal & Benson, 2011; Poteete & Ostrom, 2008), the trend in devolution has been strengthened and local irrigation institutions have become increasingly prominent across the world (Dietz et al., 2003; Pretty & Ward, 2001).

The prevalence of community-based irrigation governance is also accompanied by complex local contexts. Rapid urbanization, industrialization, and neo-liberalization have brought about varied socioeconomic changes in rural society that influence local irrigation institutions, particularly in developing countries. Against this backdrop, except for an economic analysis of key elements of community-based irrigation (Dayton-Johnson, 2003), little effort has been made to systematically and comprehensively review how local combinations of institutions and contexts may influence the performance of community-based irrigation governance.

This paper conducts a qualitative systematic review of literature on community-based irrigation governance under Social-ecological system (SES) framework (Ostrom, 2007, 2009; Petticrew & Roberts, 2006), aimed at updating the understanding of irrigation institutions in different political, socioeconomic, and ecological contexts. This review is guided by the following questions: what are the basic characteristics of community-based irrigation governance research (e.g., analysis units, methods, and study areas), what is known about the effects of different local combinations of institutions and contexts on the performance of community-based irrigation governance, and what can reported evidence reveal about the implications of local variable combinations for future research.

The remainder of this paper is organized into four sections. The first is a brief description of the methods and process of database establishment and data analysis. Second, the basic characteristics of the existing literature and their main findings are summarized. Third, there is a discussion of the implications of the combination of local institutions and contextual settings. Finally, the paper concludes with a short critical introspection.

2. Methods

2.1. Data collection

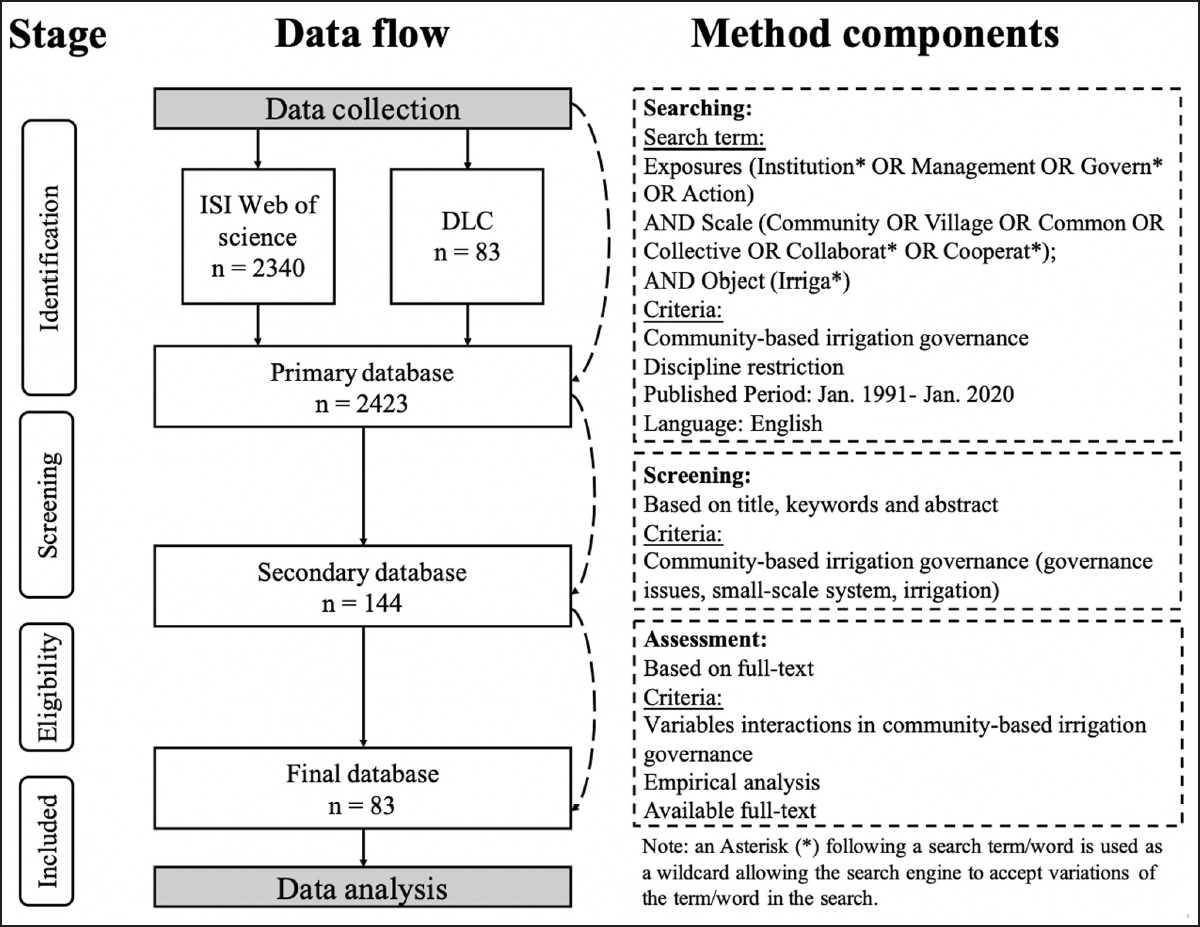

A specific search procedure and screening criteria were adopted to compile the pool of literature for analysis in this paper (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Schematic representation of the systematic review process.

First, a string of search terms was applied, which included exposure, scale, and object terms, in the ISI Web of Science and Digital Library of the Commons.2 Exposure terms limited the search to articles on issues about collective action, governance, and institutions, excluding those relating to technology and engineering issues. Scale terms limited the search to articles based on studies of community-based, village-based, or small-scale systems. Object terms limited the search to articles focused exclusively on irrigation systems rather than other CPRs. These search terms enabled us to identify and retrieve the literature relevant to the governance practices of community-based irrigation system. Second, for the ISI Web of Science database, only articles published in journals in the categories of social science, environmental science, and water resources were included and those published in other journals categories such as natural science, agriculture, or engineering were filtered. In addition, we only included English language peer-reviewed articles published since 1990 when “Governing the Commons” (Ostrom, 1990) was published. The last identification search3 was completed on Jan.18, 2020 and returned a total of 2,423 results, of which 2,340 were from the ISI Web of Science and 83 from the Digital Library of the Commons. Third, we manually examined the title, abstract, and keywords of the 2,423 retrieved articles and excluded any duplicates and irrelevant ones. The inclusion criteria are: (a) focusing on governance issues, such as management, institution, or human activity rather than crop, technology, hydrology, and engineering issues; (b) analyzing small-scale systems such as communities, villages, associations, groups, households, and individuals rather than irrigation schemes, irrigation districts, and river basins; (c) focusing on irrigation or comparing it with other natural resources rather than groundwater or domestic water supply. After this manual screening, the total number was reduced to 144. Lastly, the content of those full-text available articles was evaluated whether they are eligible and relevant to our core research questions, i.e., whether they have focused on the relationships, connections, or combinations between variables in community-based irrigation governance and how these interactions of variables affect governance performance. We also double-checked that the selected literature should be based on empirical analysis rather than pure theoretical discussion. Eventually, the compiled pool of literature consisted of 83 articles, which formed the basis of the systematic review (See Appendix A). In general, the search strategies of restriction, screening, and evaluation ensured that the returned articles were of eligible quality and provided a reasonable number to ensure a balance between perfection and feasibility for the systematic review (Petticrew & Roberts, 2006).

2.2. Data analysis

Three main procedures were used to code and analyze the 83 articles. First, bibliographic details of the articles were collected according to the following categories: method (case study, large-N study, meta-analysis, mixed study or experiment), data sources, analysis unit (community, village, system-oriented, association-oriented, household, individual, or not specified), study areas, and disciplines. We adopted the disciplinary category provided by ISI Web of Science to categorize the disciplines of each article.

Second, the main theoretical issues were identified (i.e. collective action and self-governance, sustainability of water, and water entitlement), followed by the transition of focus onto variables, which jointly characterized the intellectual development of community-based irrigation research. We have not only identified the research subject of each article according to their evaluation of governance performance but also delineated the changing attention paid to variables by scrutinizing the emerging discussions on novel variables and issues across these years.

Last but not least, we categorized, analyzed, and generalized the relationships between interactions of variables and the performance of community-based irrigation governance on the basis of the SES framework for water institutions (Hinkel et al., 2014; McGinnis & Ostrom, 2014; Meinzen-Dick, 2007; Ostrom, 2007). Through a backward-reasoning approach (Schlüter et al., 2014) and a consistent criterion (Partelow, 2018), the indicators and descriptions conforming with secondary- or third-tier variables of SES framework were identified and coded from an abstraction of the main findings, conclusions, and elaborations of the literature. We have also identified how frequently each variable is discussed by counting the variables that each article has examined. The dynamics and interactions of these indicators and descriptions were then translated into mathematical equations,4 which concisely represented the causal relationships among concepts and variables. The focus was to develop potential theoretical generalization (e.g., relationships between the combination of institutional arrangements and attributes of actors and governance performance) by comparing the mathematical equations and process relationships of secondary- or third-tier variables. This analysis was constantly moving back and forward between the generalization and the process relationship between specific variables until the conclusion can be supported by the literature. The definitions of all review parameters are illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1

Definition of review parameters.

| CATEGORY | REVIEW PARAMETER | DEFINITION |

|---|---|---|

| Method | Case study | Single case study or small-N comparative case study that contains detailed description of the cases. |

| large-N study | A quantitative analysis of large-N samples with first-hand data without description in-depth | |

| Meta-analysis | A quantitative study that revisits the existing database. | |

| Experiment | Study that conducts laboratory experiment or field experiment. | |

| Mixed study | The articles use more than one method. | |

| Data sources | Primary | The data sources used are first-hand. |

| Secondary | The data sources used are second-hand. | |

| Mixed | The data sources used combine both first-hand and second-hand ones. | |

| Analysis units | Village | Village is administrative, organizational, and historical units of a group of people. |

| Community | Community is a collective of people, who use the same CPR system without an established governance organization. | |

| System-oriented | The analysis unit of articles is community-based irrigation system. | |

| Association-oriented | The analysis unit of articles is established community-based irrigation users association. | |

| Household | Household is the organization of agricultural activities on the basis of family. | |

| Individual | Individual is the independent human that participates in irrigation activities. | |

| Not specified | The articles combine more than one type of analysis unit. | |

| Study area | Specified | The study area locates within one specific continent (i.e., Asia, Africa, Europe, North America, South America) |

| Not specified | The study areas include more than one continent. | |

| Discipline | Social science | The disciplinary category of the journal in which the articles were published is covered in the category of social science citation index. |

| Ecology | The disciplinary category of the journal in which the articles were published is environmental sciences or ecology. | |

| Water resources | The disciplinary category of the journal in which the articles were published is water resources. | |

| Interdisciplinary | The disciplinary category of the journal in which the articles were published is other categories. | |

| Research subject | Collective action and self-governance | Scholars primarily focused on community collective action, placing cooperation or self-governance as their key explained variables. |

| Sustainability of water resources | Scholars paid direct attention to the utilization of water resources and ecological conservation, concerning the efficiency, ecological, and sustainable performance of a community-based irrigation system. | |

| Water entitlements | Scholars concern with maintaining livelihood of poor rural households and ensuring equitable access and entitlement of vulnerable groups to irrigation resources. | |

| Discussion frequency of first-tier variables of SES framework | The number of articles that examine first-tier variables of SES framework as main research object or conclude findings about them. | |

The logical and interpretative consistency of screening and coding results was ensured as each article was evaluated and coded with standardized criteria by one author. Each process, criteria, and operation were also discussed adequately by both authors, who triple-checked the results and main findings. These measures minimized the degree of subjectivity and the variation of interpretation of information.

3. Results

3.1. Basic characteristics of the literature

This section presents the basic characteristics of the 83 articles based on their bibliographic information and main intellectual lines of scholarship. The details of each article are presented in Appendix B. Table 2 categorizes the literature in terms of their analysis units, study areas, methods, disciplines, and data sources. The results show that ‘village’ and ‘community’ are most commonly adopted for analysis. Other types of analysis units include specific irrigation systems, irrigation user associations, households, and individuals, which are respectively adopted in system-oriented studies, association-oriented studies, and behavioral or perception-based studies. Besides, Asia is the most popular study area with a particular focus on India (frequency = 14) and China (frequency = 13). Studies of Asia occurred in most of the years from 1995 to 2019. In addition, multiple disciplines are involved in the study of community-based irrigation governance. Most studies fall in the scope of ‘social science’, ‘water resources’, and ‘ecology’.

Table 2

(1) Analysis unit of articles (2) Study areas (3) Method of studies (4) Disciplinary (5) Data sources used.

| (1) ANALYSIS UNITS | NO. | (2) STUDY AERAS | NO. | (3) METHODS | NO. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Village | 22 | Asia | 50 | Case study | 40 |

| Community | 17 | Africa | 11 | large-N study | 27 |

| System-oriented | 15 | Europe | 6 | Meta-analysis | 7 |

| Association-oriented | 10 | North America | 5 | Experiment | 5 |

| Household | 6 | South America | 3 | Mixed study | 4 |

| Individual | 5 | Not specified | 8 | ||

| Not specified | 8 | ||||

| (4) DISCIPLINES | NO. | (5) DATA SOURCES | NO. | ||

| Social science | 47 | Primary | 74 | ||

| Water resources | 19 | Secondary | 7 | ||

| Ecology | 16 | Mixed | 2 | ||

| Interdisciplinary | 1 |

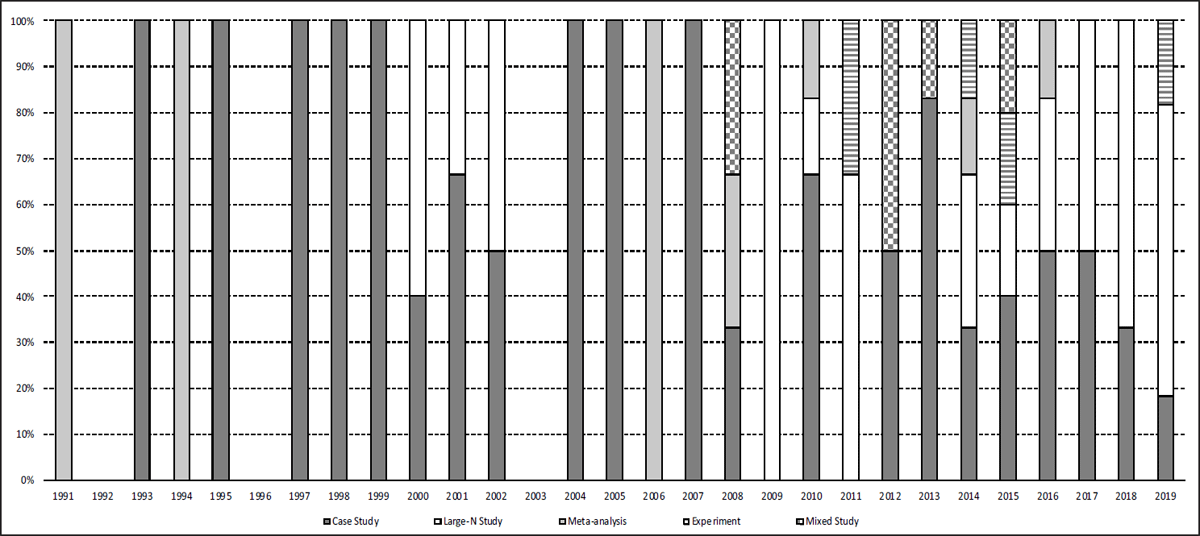

For research methods, most of the articles adopted single or comparative case studies, followed by large-N studies, meta-analysis studies, experimental studies, and mixed studies. Figure 2 illustrates a paradigmatic shift towards quantitative and multiple approaches in community-based irrigation studies. In recent years, the proportion of large-N, experimental, and mixed studies has increased while that of case studies has declined. Meta-analysis that updates theoretical advancement appears every few years. Owing to the evidence-based research methods widely adopted in the literature, primary data dominated the sources for research, while secondary and mixed data were used only occasionally.

Figure 2

Proportions of different research methods used by the selected articles (1991–2019).

After screening the literature, we identified three main research subjects in the community-based irrigation studies, namely collective action and self-governance, sustainability of water resources, and water entitlements. First, drawing on the paradigm of individual rationalism, a group of scholars primarily focused on elements that promote or impede community collective action in CPR dilemma situations, placing individual behaviors such as cooperation, self-governance, and collective action of local community as their key explained variables. Both institutional and structural paths have been taken into the analysis of explanatory variables. On the one hand, the institutional path is concerned with how institutional incentives may facilitate cooperation in irrigation governance. For example, scholars have explored how different institutional arrangements, such as appropriation rules, provision rules, communication rules, decision-making rules, and governance structure, may affect the collective action (Araral, 2009; Kurian & Dietz, 2004; Sijbrandij & Van Der Zaag, 1993; Tang, 1991; Trawick, 2001; Vandersypen et al., 2007). On the other hand, the structural path answers in what ways cooperation may be influenced by community structures (Dayton-Johnson, 2003), such as size of irrigation system (Meinzen-Dick et al., 2002; Trawick, 2002; Wang & Wu, 2018), number of water users (Ireson, 1995; Norman, 1997), degree of heterogeneity (Baker, 1997; Ruttan, 2006; Luo et al., 2019), landholding situation (Bardhan, 2000; Dayton-Johnson, 2000a; Zang et al., 2019). These studies were motivated by the pursuit of a better mode of community-based irrigation governance and aimed at addressing the dilemma of collective action. Notably, these studies compose the mainstream scholarship that has initiated and dominated most community-based irrigation governance research.

Second, from a broader ecological perspective, scholars also paid direct attention to the utilization of water resources and ecological conservation, concerning how biophysical, ecological, socioeconomic, and managerial factors affect the economic and ecological performance of a community-based irrigation system, such as efficiency and equity of water delivery and use (McCord et al., 2017; Ruttan, 2006; Trawick, 2002; Uphoff & Wijayaratna, 2000; Yu et al., 2016), agricultural production (Norman, 1997; Thapa & Scott, 2019; Villamayor-Tomas, 2014; Yercan et al., 2009), and ecological externality to other ecological systems (Bahinipati & Viswanathan, 2019). In this line of inquiry, the local community-based irrigation systems are regarded as part of the broader water resources and ecological system (Lam & Chiu, 2016; Cody, 2019), of which scholars are particularly concerned about the sustainability.

Last, different from the aforementioned scholarships that aimed at seizing the thumbnail rules for achieving “good governance”, a few scholars chose to focus on the water entitlements within local community. Deriving from notions of moral economy (Scott, 1976), they emphasized the effects of tradition, power relationships, value systems, and moral norms on local irrigation governance, centrally concerning with the livelihood of poor households and ensuring equitable access and entitlement of vulnerable groups to irrigation resources in a community. For example, Mosse (1997) illustrates that the institutions of controlling tank water are not maintained by moral code but serve the interest of the dominant group of the community. Also, Cleaver (2000) identifies that people’s heterogeneous identities conferred by kinships or division of labor determine a hierarchy of community members who have uneven access to water. This intellectual path also argues that institutional arrangements are shaped by historical process, embedded in historical context, and entwined in interpersonal daily interactions rather than being crafted by individual decision-making and rational choice (Cleaver, 2012; Mosse, 1997), thus calling for a historical and contextual understanding of the myriad relations on which institutions and governance are based. Although the water entitlement scholarships are normatively, epistemologically, and methodologically different from the other two scholarships mentioned above, they converge on the analysis of rules and embrace the notions that institutions affect irrigation governance (Johnson, 2004).

3.2. Variables trends: institutions, context, and performances

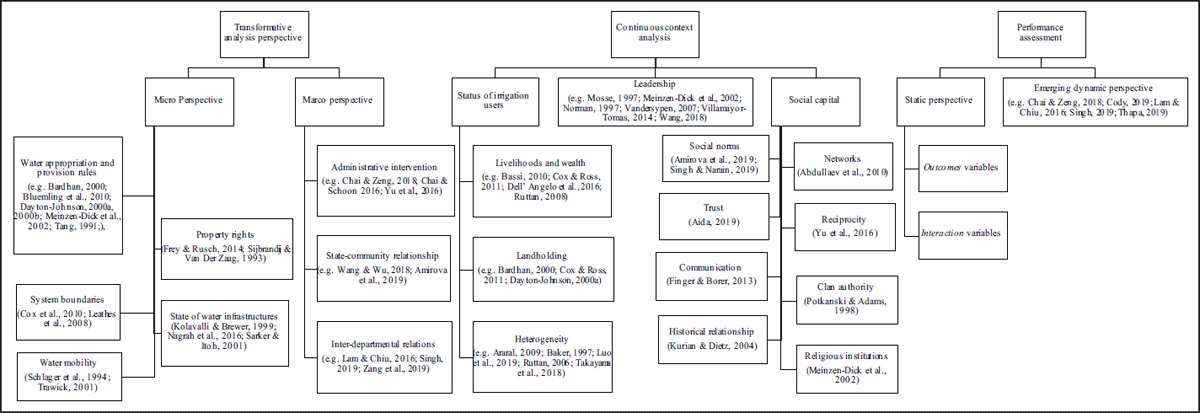

In addition to the basic characteristics, general trends in the development of community-based irrigation literature were identified (See Figure 3), based on the three variables, namely institutions, context, and performance measurement.

Figure 3

Summary of development trends in examined variables of the reviewed articles.

First, the conceptualization of institutions and context illustrates that the traditional micro-analysis has been progressively incorporated with a macro perspective. Research began with how specific operational rules affect collective action under micro biophysical contexts of irrigation systems. The research subjects included water appropriation and provision rules (Bardhan, 2000; Bluemling et al., 2010; Dayton-Johnson, 2000a, 2000b; Meinzen-Dick et al., 2002; Tang, 1991), property rights (Frey & Rusch, 2014; Sijbrandij & Van Der Zaag, 1993), system boundaries (Cox et al., 2010; Leathes et al., 2008), state of water infrastructures (Kolavalli & Brewer, 1999; Nagrah et al., 2016; Sarker & Itoh, 2001), water mobility (Schlager et al., 1994; Trawick, 2001), and so forth. Broader governance structures were then incorporated into analysis, which involved administrative intervention (Chai & Zeng, 2018; Chai & Schoon, 2016; Yu et al., 2016), state-community relationship (Wang & Wu, 2018; Amirova et al., 2019), and inter-departmental relations (e.g. rural-urban in Singh, 2019; institutional nesting in Lam & Chiu, 2016; land-irrigation in Zang et al., 2019). These subjects have been associated with the analysis of local institutional capacity for self-governance, decision-making, and implementation of rules. This shift has not only extended the analytical scope from observable and operable values to abstract concepts but has also lifted the restrictions on community and biophysical irrigation systems per se and paid more scholarly attention to government-community relationships and the macro context of irrigation systems. In other words, the literature of community-based irrigation governance has combined broader governance issues and theories with specific rules, associated local contexts with socio-political environments, and has linked individual communities with multiple governmental agencies, thereby supplementing micro analyses with macro insights.

Second, the literature has continuously focused on three groups of contextual variables of attributes of actors, namely status of irrigation users, leadership in rural communities, and social capital. Specifically, researchers have focused on livelihoods and wealth (Bassi, 2010; Cox & Ross, 2011; Dell’ Angelo et al., 2016; Ruttan, 2008), landholding (Bardhan, 2000; Cox & Ross, 2011; Dayton-Johnson, 2000a), and heterogeneity among water users to reflect the status of irrigation users (Araral, 2009; Baker, 1997; Luo et al., 2019; Ruttan, 2006; Takayama et al., 2018). Likewise, power, authority, and the position of village cadres or irrigation managers have been used to unpack leadership (Mosse, 1997; Meinzen-Dick et al., 2002; Norman, 1997; Vandersypen et al., 2007; Villamayor-Tomas, 2014; Wang et al., 2018). Social capital, however, involves a miscellaneous set of complex variables ranging from social norms (Amirova et al., 2019; Singh & Narain, 2019), networks (Abdullaev et al., 2010), trust (Aida, 2019), reciprocity (Yu et al., 2016), and communication (Finger & Borer, 2013) to clan authority (Potkanski & Adams, 1998), historical relationship (Kurian & Dietz, 2004), and religious institutions (Meinzen-Dick et al., 2002). The continuous attention paid to these local attributes consists of diverse concepts and theories, which illustrate both the complexity and development of local contextual analysis.

Third, in terms of performance assessment, scholars have increasingly measured governance performance of community-based irrigation systems by using Outcomes variables in the SES framework, such as equity in allocation of benefits (Dörre & Goibnazarov, 2018; Nagrah et al., 2016), efficiency in water supply and conservation (McCord et al., 2017; Yu et al., 2016), livelihood contributions from irrigation (Amirova et al., 2019; Frey & Rusch, 2014), and ecological externality (Bahinipati & Viswanathan, 2019; Bastakoti et al., 2010; Singh & Narain, 2019). This shift contrasts with the traditional approach, which focuses on the degree of collective action and measures performance according to Interaction variables under the incentives of institutions and socioeconomic structures (Bardhan, 2000; Tang, 1991; Schlager et al., 1994). In this sense, the conceptualization of governance performance has increasingly incorporated diverse perspectives, including moral, economical, and ecological principles during governance process, thus setting higher epistemological and methodological requirements for researchers.

Moreover, a growing body of literature has examined the performance of community-based irrigation systems from a dynamic perspective in recent years. This emerging research perspective is centrally concerned with the extent to which and how rural communities have succeeded or failed in adapting to and coping with external transformation. For instance, it has been shown that local community is able to adjust their institutional arrangements to adapt to changes in the macro contexts (Lam, 2001). Different adaptation strategies adopted by local farmers could influence the robustness of irrigation systems in a transitional economy (Lam & Chiu, 2016). Facing climate abnormality and climate change, local community could restore irrigation system to a robust state through revising rules with the support of social capital (Chai & Zeng, 2018). Similarly, community with internalized norms of cooperation tends to enforce rules to sustain the irrigation system (Cody, 2019). Farmers also expand their water sources and evolve corresponding institutions to adapt to the increasing water stress (Singh, 2019; Thapa & Scott, 2019).

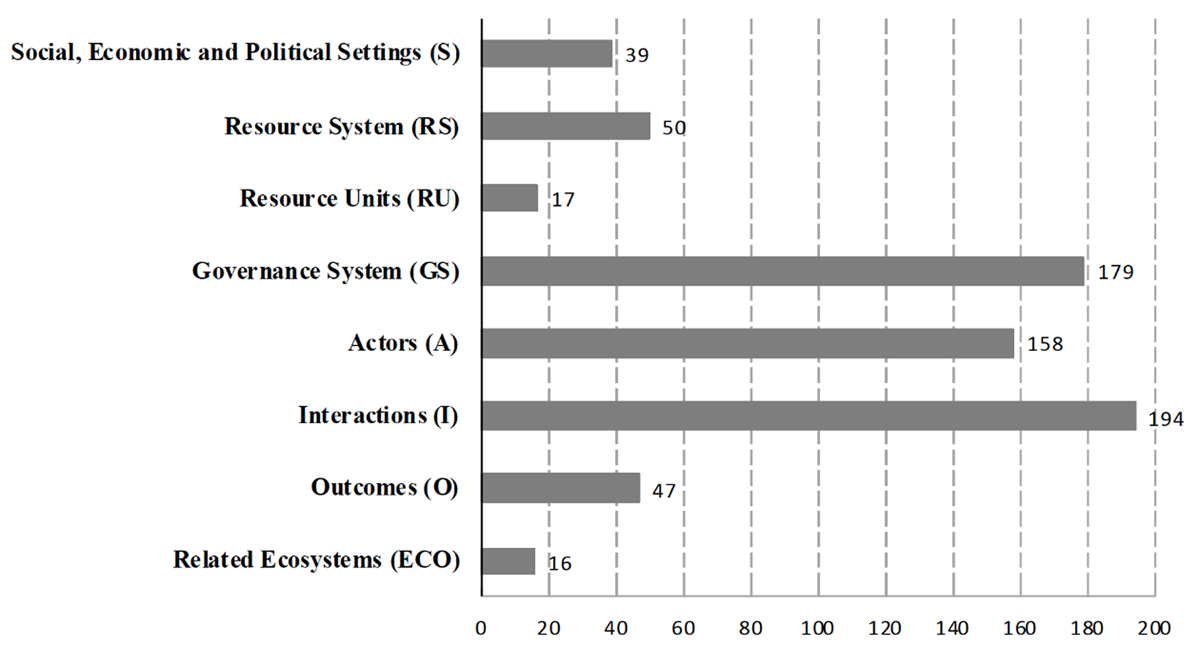

Overall, differentiated attention has been paid to specific variables in the community-based irrigation literature (see Figure 4). Situating these variables in first-tier variables of SES framework, it was found that variables in the category of Interaction were examined more frequently (194 times) than those in Outcomes (47 times), Social, Economic and Political Settings (39 times), and Related Ecosystems (16 times). As for subsystems that influence interaction and outcomes in the SES, most discussions concentrated on social system variables such as Governance System (179 times) and Actors (158 times) rather than biophysical and ecological systems such as Resource System (50 times) and Resource Units (17 times).

Figure 4

Discussion frequency of first-tier variables of SES framework.

3.3. The effects of combinations of local institutions and contexts on irrigation performance

Previous studies have reviewed the effects of individual variables and configurations of DPs on governance of the commons (Agrawal & Benson, 2011; Baggio et al., 2016; Cox et al., 2010; Dayton-Johnson, 2003). However, it has also been established that the presence or absence of an individual variable and single-dimensional factor is not sufficiently informative as the outcome of a CPR system cannot be isolated from configurations of different institutional factors in specific socio-ecological settings (Baggio et al., 2016; Lam & Ostrom, 2010; Wang et al., 2018). This review builds on these previous studies by analyzing how combinations of local institutional variables and their contextual settings may influence the performance of community-based irrigation systems. We specifically describe which institutional arrangements are more likely to improve or impede governance performance under particular contextual conditions.

First, one of the most commonly seen combinations relates to institutions and attributes of actors, such as group size, group heterogeneity, and social capital. The congruence of these two variables is important for promoting cooperation and improving irrigation performance (Baggio et al., 2015; Dell’Angelo et al., 2016; Norman, 1997; Tang, 1991). Specifically, it is suggested that clearly defined property institutions combined with a small group of farmers, and full autonomy-related institutions combined with a large group of heterogeneous farmers, are more likely to solve collective action problems and achieve successful outcomes (Araral, 2009; Norman, 1997). Similarly, established management organizations commanding larger hydrological areas result in irrigation devolution programs that are most likely to succeed (Meinzen-Dick et al., 2002). Also, a contractor-based institution enables relatively heterogeneous groups to successfully comply with rules through collective action when the water user group lacks alternative irrigation sources, the contractor shows strong leadership, and there is a high degree of dependence on irrigation water (Kurian & Dietz, 2004). Likewise, designed self-governing organizations and institutional arrangements, combining with internalized social norms, values, morality, and informal rules, tend to ensure more rule compliance and generate better performance in dealing with deficient water supply and improving the resilience of irrigation systems in extreme climatic conditions (Cody, 2019; Uphoff & Wijayaratna, 2000). If flawed institutions are combined with low social capital and abuse of power, the community is less likely to cope with external disturbances, thereby leading to poor performance (Theesfeld, 2004).

Second, in addition to attributes of actors, it is also suggested that the combination of institutions and contexts of resource systems and related ecosystems (e.g., hydrology, soil, and agriculture) may account for the performance of irrigation management. In terms of hydrology, water scarcity is a frequently mentioned contextual variable. Under severe hydrological circumstances of limited, fluctuated and asymmetric access to water, diversified and flexible rules may contribute to the coordination of water supply and its equitable distribution, which then alleviates the negative impact of water scarcity on collective action (Trawick, 2001; Zhou, 2013). For instance, it is suggested that fully autonomous organizations are better able to deal with the negative effects of water scarcity on financial free-riding compared with non-autonomous organizations (Araral, 2009). Similarly, during periods of drought, transfer rules of water quotas that allow flexible water reallocation among irrigation systems may enhance cooperation and contribute to irrigation performance (Villamayor-Tomas, 2014). In addition to water scarcity, the co-occurrence of clearly defined hydrological boundary and property rights and the combinations of water mobility and irrigation infrastructure with graduated sanctions are positively related to the success of irrigation systems (Baggio et al., 2016). When combining agricultural conditions and institutions, the stronger water-holding capacity of soil may compensate for any weaker formal monitoring institutions and a lack of water quota transfer, thereby contributing to productivity and cooperation, and vice-versa (Villamayor-Tomas, 2014). The congruence between the patterns of agricultural production and water allocation rules has a positive effect on irrigation outcomes (Niranjan, 1998; Norman, 1997; Zang et al., 2019).

Third, the combinations of irrigation institutions and proximity to market are also considerable for the performance of irrigation management. The proximity to market is usually indicated by the distance between an irrigation system and a commercial center in recent literature. It is suggested that irrigation devolution programs are more likely to succeed if formal irrigation organizations are located closer to market centers (Meinzen-Dick et al., 2002). The longer history and greater autonomy of irrigation organizations that are near commercial centers may considerably lessen the odds of labor free-riding occurring in irrigation governance (Araral, 2009). These conclusions unpack the joint effect of irrigation institutions and their association with market on governance outcomes. However, the metrical indicator of spatial proximity seems an oversimplification of the impacts of complex market processes and market incentives. For example, it is also suggested that increasing integration with the market may negatively affect the coordination and implementation of CPR institutions (Agrawal & Yadama, 1997), which raises theoretical questions about what impacts (e.g., positive or negative) the market may bring to community-based irrigation governance through which path (e.g., commercialization, industrialization, or urbanization) (Ostrom & Gardner, 1993; Meinzen-Dick et al., 1997). In other words, many more intermediary links, besides geographical association, between the market and local irrigation system have not been fully exposed and measured. Other indicators such as rural-urban migrants and non-farming income may be considered to supplementarily measure and enrich the multifactual dimensions of market incentives.

In summary, three major groups of contextual variables, identified as attributes of actors, contexts of resource systems and related ecosystems, and market incentives, have emerged from the literature and have been combined with institutional arrangements for irrigation. An analysis of the combinations of local institutions and socio-ecological settings allows this research to go beyond the traditional approach and understand how the effects of individual variables or single-dimensional factors may be moderated or adjusted by their combination with other variables. This means that the same institutional arrangements may be effective in a certain context but ineffective in another. By analyzing the combinations of variables, further understanding is gained of the complex mechanisms leading to the success or failure of irrigation governance under various conditions.

4. Discussion

This section presents the implications of the results of combinations of local institutions and contexts. First, the performance of irrigation systems may depend on the close and diverse relationships between institutional and contextual variables. Second, the interconnectedness of institutions and local contexts encourages a focus on specific combinations for understanding CPR governance. Lastly, two types of research approach for devolving specific combinations have been identified. These implications highlight the complexity of irrigation governance and the diversity of local combinations.

4.1. Exploring the combinations

Specific types of institutional arrangements and different contexts work together, rather than in isolation. It is their interdependence and degree of coordination that affect irrigation performance. On the one hand, the effects of combinations of local institutions and contexts are fundamentally different from those of single variables. Some contextual variables such as water scarcity, heterogeneity, and large group size are found to negatively influence collective action in a conventional analysis; however, the occurrence of these contextual variables does not necessarily result in relatively poor performance when combined with specific institutions such as fully autonomous management organizations (Araral, 2009). Therefore, the effect of institutions and contexts on irrigation performance are not parallel, independent, or equally effective; rather, they are interactive, converging, and may be mutually neutralized or counteracted. On the other hand, the combination of specific institutions and contexts can make their effects explanatory and meaningful. For example, a single variable of agricultural planting patterns or water allocation rules does not determine the success or failure of irrigation system governance; however, uniform agricultural crop planting by all farmers combined with synchronistic rules of water allocation could explain the achievement of collective action (Niranjan, 1998).

This review indicates that it may be possible to successfully combine two institutions with different contextual dimensions. One is the clearly defined property institutions that may result in successful outcomes among community-based irrigation systems with specific contexts of clearly defined hydrological boundaries or small group sizes (Baggio et al., 2016; Norman, 1997). Another is fully autonomous organizations, which may encourage collective action when combined with water scarcity, with a location close to the market, or with large heterogenous groups (Araral, 2009). Furthermore, different institutions may bring about desirable outcomes in similar contexts. For instance, it has been shown that both contractor-based institutions and fully autonomous organizations, when combined with larger heterogeneous groups, may result in rule compliance and collective action (Araral, 2009; Kurian & Dietz, 2004). This highlights the flaws of debating the efficacy of institutional arrangements without considering local contexts and the need to compare institutions based on scrutiny of the local contexts in which they operate.

In addition, it should be noted that the degree and/or dimension of success or failure might not be the same in different combinations. This further demonstrates the diversity and complexity of combinations and warrants further research into this contextual sensitivity of institutions.

4.2. The interconnectedness of institutions and local contexts

The importance of the combination of institutions and contexts has been emphasized; however, it is also notable that institutions are tightly interconnected with local contexts. To be specific, local contextual settings matter to the formation and implementation of institutional arrangements (Ostrom, 2005). From an institutional choice perspective, multiple socio-ecological conditions influence transaction costs (arising from incomplete information and uncertainty during multiple resource appropriation games) and then incentivize individual agencies to design and implement institutional arrangements.

Evidence from the literature has shed some light on how contextual settings may interconnect with and shape institutions. For example, the physical characteristics of irrigation infrastructure, whether it is a canal, lift, or tank irrigation system, are connected with appropriation rules and property institutions (Kolavalli & Brewer, 1999). Also, attributes of actors (e.g., external assistance, local leadership with authority, and economic heterogeneity) may affect the formation and function of institutions. For instance, government and non-governmental organizations, with the aim of strengthening local institutional capacity, may provide financial support or organize local communities to form WUAs (Bassi et al., 2010). Local leadership characteristics (e.g., education, age, experience, and charisma) and their role in organization, coordination, mobilization, and discretionary decision-making may affect institutional agenda setting, arrangements, and implementation (Fu et al., 2010; Hamidov et al., 2015; Ireson, 1995; Vineetha et al., 2005). In addition, power asymmetries among community members may also shape the outcome of institutions; those with more land are more likely to dominate the institutional deliberation process, therefore the results often reflect the will of the more powerful members (Komakech et al., 2012).

This interconnectedness reinforces the significance of understanding CPR governance from the perspective of combinations of institutions and contexts. The concomitant of specific institutions and contexts can evolve into a fixed combination (Partelow, 2018), which may be associated with relatively stable and predictable outcomes. For example, monitoring institutions combined with the physical characteristics of a community-based irrigation system can be interpreted as a specific combination. Owing to the limited mobility of irrigation water, the static nature of established canals, the observable amount of water in canals, and the sensitivity of water users to a change of water quantity, the cost of monitoring is low in the community-based irrigation system, especially for those on steep slopes (Cifdaloz et al., 2010; Trawick, 2001). As a result, a community-based irrigation system is more amenable to monitoring than other CPR systems (Baggio et al., 2016) and monitoring therefore is often suggested as an effective institutional arrangement. In this sense, fixed combinations could be the basis for potential inquiries into regularities of governance performance. Future studies could try to identify the existing fixed combinations in a range of cases and include more variables of institutions and contexts into an analysis of the interactions and effects of multiple variables in CPR governance.

4.3. Two research approaches

Scholars have adopted five main research methods to analyze the conditions of community-based irrigation governance performance (see Table 2 and Figure 2). Two research approaches have been used to explore the effects of local combinations. The large-N study distinguishes the performance discrepancy between outcomes, in which the combination of certain institutional and contextual variables is absent or present. This path is concerned with the extent to which certain combinations may influence performance, thus exploring the generalizability and external validity of these findings. Interaction-effects analysis in the ordinary least squares (OLS) regression model was undertaken to examine the effect of combinations of institutional arrangements and socio-ecological characteristics on collective action (Araral, 2009), while qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) was applied to test the effect of configurated DPs combining with certain contextual variables on the performance of irrigation systems (Baggio et al., 2016).

The other approach used is the comparative case study, which considers the diversity of certain combinations and their relationships with governance outcomes (Lam, 2001; Lam & Chiu, 2016). This approach assists in understanding the nuances in the diverse relationships and the complex interconnections of institutional arrangements and contextual settings. The complexity of irrigation systems results in a high degree of diversity, which is revelatory and informative, offering relatively reliable explanations of observed successful or failed governance performance within a specific scope of analysis.

5. Conclusion

The performance of CPR governance is contextually sensitive. However, the effects of combinations of specific local institutions and their contexts on the success or failure of CPR governance are still not understood fully. Through the lens of community-based irrigation systems, this paper conducted a qualitative systematic review of English-language academic articles to examine the complexity of a CPR system and how combinations of institutional and contextual variables affect the performance of irrigation governance.

The paper begins with a summary of the characteristics and development trends in the community-based irrigation governance literature over the past three decades, including units of analysis, methods, sources of data, and the main research subjects. There then follows an illustration of the development of the literature through an elaboration of variables of institutions, context, and performance measurement. Institutional arrangements for irrigation have been mostly associated with attributes of actors, contexts of resource system and related ecosystems, and irrigation systems’ spatial proximity to market in the literature, revealing the effects of three major combinations of institutional and contextual variables on the performance of irrigation governance. Finally, areas to explore further are discussed relating to the combinations, the system complexity, and contextual sensitivity. The interconnectedness between institutions and local contexts, and appropriate research approaches to examine the combinations are also discussed.

The qualitative systematic review allows us to highlight some areas of combinations between contexts and institutions in need of further endeavor. First, there remain more potential combinations of contextual settings and institutional arrangements that have not been fully discussed. Specific institutions can be examined under more types of contextual settings, such as the physical characteristics of irrigation infrastructure, external intervention, polycentric structure, and so forth. These combinations may generate new insights into the mechanisms of community-based irrigation governance. Second, we have provided evidence about the combination of one specific contextual property of community-based irrigation system with one specific institution. The combination of a bundle of contextual properties with a bundle of institutional arrangements needs to be discussed. Third, the complexity of contextual variables needs to be processed carefully. One should be conscientious about designing appropriate indicators that could accurately measure the complex and transformative contextual variables. For example, the spatial proximity to market could be one of the indicators that may overreach its theoretical argument because it only reflects one dimension of a complex context. Under this vein, intermediary mechanisms between the effect of combinations on community-based governance performance also worth further investigation. The existing literature have unpacked some mechanisms between single variables and performance. However, it is inadequately understood how specific combinations bring about certain governance performance and why similar combinations may result in different outcomes. Answering this question could help us understand the full picture of institutions and inform future institutional and policy design within a given context. Finally, it is of great significance to further explore and understand the combinations between institutions and contextual settings in other CPR systems, such as forests, fisheries, and pastures, and at different scales (e.g., larger-scale irrigation system, irrigation scheme, and groundwater). For example, as group size increases, enforcing institutions through stricter monetary sanction may be detrimental for community-based forest protection (Agrawal & Chhatre, 2006). In a larger-scale ocean ecosystem, where the depletion of whale stocks is difficult to detect precisely and the regeneration rate of whales is low, the institutions of managing fisheries proved severely deficient for the sustainability of whaling (Young, 2002). The understanding of these combinations of variables varies significantly across different CPR systems; because the combinations may manifest in different ways and play a heterogenous role in shaping the performance when the CPR systems change. The failure of one-size-fix-all arrangements encourages us to explore specific combination of contexts with institutions across different biophysical and socioeconomic settings.

Additional files

The additional files for this article can be found as follows:

Notes

[1] Irrigation Management Transfer (IMT) and Participatory Irrigation Management (PIM) also involve large-scale irrigation systems. For example, IMT occurred at the irrigation districts in Mexico (Rap and Wester, 2013) and PIM was introduced to manage a large-scale irrigation system in Harran Plain, Turkey (Özerol, 2013).

[2] The Digital Library of the Commons is a gateway to the international literature on the commons (http://dlc.dlib.indiana.edu/).

[3] This search is supported by the search engine of ISI Web of Science and Digital Library of the Commons database. Researchers can restrict their retrieved results by choosing proper searching restriction options in the database, such as publication date, language, format, etc. The three restricted disciplinary categories i.e., social science, environmental science, and water resources are most relevant to our critical research questions among the categories in the search engine of ISI Web of Science database.

[4] The mathematical equation represents interactions between second-tier or third-tier variables by an arrow interlinking the codes of variables in the SES framework followed by a positive or negative sign to indicate the direction of their correlation. For example, “S5&GS6 → I5 [-]” represents greater autonomy of irrigation organizations (GS6) that are near to commercial centers (S5) may lessen the odds of labor free-riding (I5) occurring in irrigation governance (Araral, 2009). This processing allows researchers to discern the relationships of variables interactions and to merge the specific relationships of variables into broader categories for further theoretical generalization.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers and the editor for their comments and suggestions. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [41801132]; the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province [2018A030313964]; and the Humanities and Social Science Fund of Ministry of Education of China [17YJCZH183].

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.