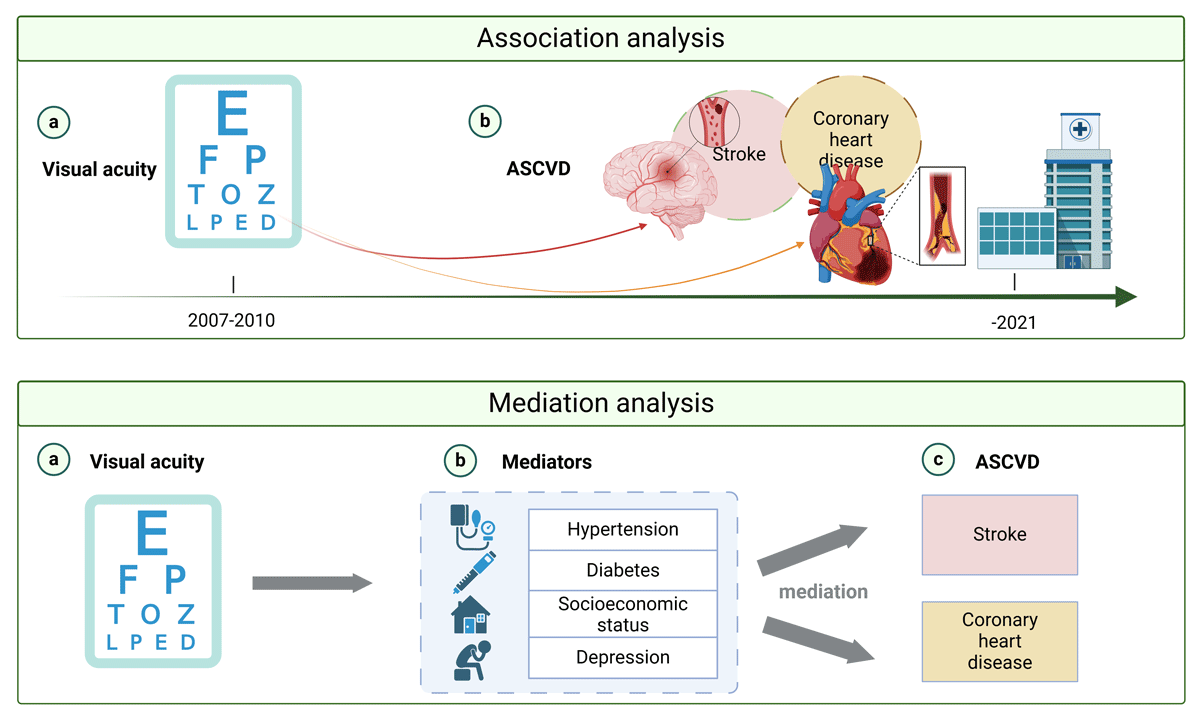

Graphical Abstract

Visual acuity and ASCVD in middle-aged and older adults.

What is already known

Visual impairment, including glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy, which affect vision, is associated with risk factors for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), such as diabetes and hypertension. However, the association between the full spectrum of visual acuity (VA) and ASCVD has not been fully explored. Nevertheless, there is still a lack of research examining the common risk factors for VA and ASCVD and their mediating effects.

What this study adds

This study identifies that visual decline is independently associated with an increased risk of ASCVD, highlighting the importance of early intervention through regular eye exams.

It reveals that depression and socioeconomic status have a greater mediating effect on the VA-ASCVD association than traditional risk factors like hypertension and diabetes.

The findings underscore the need to address mental health and socioeconomic disparities to reduce ASCVD risk, particularly in older women with visual impairments.

Introduction

As the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) events account for approximately 17.6 million deaths annually and have significant financial impacts worldwide (1). The recently published ACC/AHA Guidelines on Prevention of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease in Adults emphasize the usefulness of a risk-based approach to CVD and implementing lifestyle and medical interventions to prevent adverse cardiovascular events (2). Observational studies further demonstrate that while genetics cause a low-level ASCVD risk, much of this can be overcome by maintaining a healthy lifestyle and avoiding risk factors throughout early life (3).

Visual acuity (VA) is associated with adverse physical and psychological outcomes (4). Research shows that visually impaired adults face a higher risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and mortality compared to those with normal vision (45). This association may be partially attributed to conditions such as glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy, which are strongly linked to traditional ASCVD risk factors like diabetes and hypertension (678). Moreover, authoritative guidelines emphasize the importance of managing diabetes and hypertension to mitigate ASCVD risk (91011). These two conditions, as major contributors to both cardiovascular risks and retinal complications, highlight their role as shared pathways connecting visual impairment (VI) and cardiovascular health.

Beyond these traditional risk factors, depression and socioeconomic status also play significant roles in both visual and cardiovascular health. Depression has emerged as a major contributor to ASCVD, with evidence pointing to mechanisms such as chronic inflammation, hormonal imbalances, and reduced health behaviors (1213). Similarly, socioeconomic status influences health outcomes by limiting access to medical care, increasing exposure to chronic stress, and exacerbating health disparities (1415). Studies suggest that individuals with low socioeconomic status are more likely to experience both ASCVD and poorer vision, possibly due to barriers to healthcare, education, and access to nutritious food (161718). Depression and socioeconomic deprivation have also been associated with delayed eye care and reduced quality of life, further compounding the risk of both VI and ASCVD (19).

Despite these well-established associations, there is limited evidence exploring whether VA itself serves as an independent predictor of ASCVD or whether the relationship is mediated through long-term exposure to these risk factors. Given that a large proportion of ASCVD events occur in patients without known cardiovascular disease (2), exploring the association between VA and ASCVD may help provide a comprehensive framework for risk stratification and early intervention strategies to reduce ASCVD incidence and related mortality.

Building on the well-documented relationships between VA and key risk factors for ASCVD, including hypertension, diabetes, depression, and socioeconomic status, we hypothesized that VA would independently predict ASCVD events. Additionally, given the dual impact of these factors on both visual and cardiovascular health, we proposed that the association between VA and ASCVD may be partly mediated through these pathways. To test these hypotheses, we utilized the UK Biobank, a large and diverse prospective cohort study, enabling a longitudinal analysis of the relationships and pathways between VA and ASCVD.

Methods

Study Sample

The UK Biobank is a national, prospective study aimed at identifying determinants of complex diseases and improving health outcomes in British adults. Of 9.2 million NHS participants aged 40–69 years invited, over 500,000 (5.5% response rate) participated in baseline assessments from 2006 to 2010. Data collection included questionnaires, physical measures, and biological samples, with long-term follow-up for health outcomes (20). Ophthalmic assessments were introduced to the baseline assessment in 2009 for six assessment centers.

The UK Biobank received ethical approval (Ref 11/NW/0382), and informed consent was obtained from all participants. Methods, protocols, and definitions are detailed on the UK Biobank website (https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/). Data for this analysis were provided under project reference #86091, with the participant selection process outlined in Supplementary Figure 1.

Visual Acuity Testing at Baseline

The procedure for VA testing in the UK Biobank Study has been described in detail elsewhere (21). Presenting distance, VA was measured with corrections (if any) at a 4 m distance using the logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (logMAR) chart (Precision Vision, LaSalle, Illinois, USA) on a computer screen. Presenting VA was scored as the total number of correctly read lines, converted to logMAR units, where lower values indicate better visual acuity and higher values indicate poorer visual acuity. The present analysis is based on the presenting VA in the better-seeing eye. VA was modeled as both a continuous variable (per 0.1 logMAR increase) to evaluate the linear association between VA and ASCVD risk and as a categorical variable divided into tertiles (T1: highest VA, T3: lowest VA) to examine potential dose-response relationships.

Ascertainment of Incident Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease

ASCVD cases in the UK Biobank Study were ascertained by combining data from participants’ medical history (UK Biobank Field 20002), record linkage to hospital admissions data (UK Biobank Field 41270), and the national death register (UK Biobank Field 40001). The hospital admissions data and the national death register data were defined using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes. Incident ASCVD was defined as the first occurrence of coronary heart disease (CHD) events (myocardial infarction (ICD-10 codes I21–I23), resuscitated cardiac arrest (ICD-10 codes I46.0), and fatal CHD (ICD-10 codes I20–I25)) or stroke (fatal and non-fatal events (ICD-10 codes I60–I64)). The present study excluded participants with ASCVD diagnosis at baseline. Follow-up time was calculated as the duration between the date of the first assessment and the earliest occurrence of ASCVD, death, loss to follow-up, or the end of the study period.

Potentially mediating factors

In this study, the potential mediators for the association between VA and ASCVD that were selected for mediation analysis included hypertension, diabetes, depression, and Townsend deprivation indices. A significant indirect role (mediation) was deemed present when the following conditions were met: (a) a significant relationship existed between the independent variable and the mediator, (b) a significant relationship existed between the independent variable and the dependent variable, (c) a significant relationship existed between the mediator and the dependent variable, and (d) the association between the independent and dependent variables, known as the direct role, was attenuated when the mediator was included in the regression model (22).

For baseline assessment: 1) hypertension was defined as self-reported (UK Biobank field: 20002), the use of antihypertensive drugs (UK Biobank field: 6153), and average systolic blood pressure of at least 130 mmHg (UK Biobank field: 4080) or average diastolic blood pressure of at least 80 mmHg (UK Biobank field: 4079); 2) diabetes was defined as doctor-diagnosed diabetes mellitus, (UK Biobank field: 2443), the use of anti-hyperglycemic medications (UK Biobank field: 20003) or insulin (UK Biobank field: 6153), or glycosylated hemoglobin level of >6.5% (UK biobank field: 30750); 3) depression was defined as self-reported (UK Biobank field: 20002) or had a score on the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ, the first two items) of at least 3 (UK Biobank field: 2050 and 2060); 4) each participant was assigned a Townsend deprivation index (UK Biobank field: 189), which is used as a proxy for socioeconomic status and calculated based on the preceding national census output areas. The score is based on four variables: households without a car, overcrowded households, households not owner-occupied, and persons unemployed (23).

For longitudinal assessment, linked hospital admission records also identified a primary or secondary diagnosis of hypertension (ICD-10 codes I10–I15), diabetes (ICD-10 codes E10–E14) and depression (ICD-10 codes F32 and F33). And these cases only occurred after the date of baseline assessment and before the date of onset ASCVD was included in the mediation analysis.

Covariates

Potential confounders in the present analysis include age, sex, ethnicity (recorded as white and non-white), education attainment (recorded as college or university degree, and others), family history of ASCVD (a marker of biological vulnerability), smoking status (recorded as current/previous and never), physical activity level (recorded as above moderate/vigorous/walking recommendation or not) and hyperlipidemia (defined as self-reported, the use of hyperlipidemia-related medication or statins or with a blood cholesterol level ≥ 6.21 mmol/L), systolic and diastolic blood pressure (measured in mmHg), HbA1c levels (measured in mmol/mol), LDL (measured in mmol/L), HDL (measured in mmol/L), triglycerides (measured in mmol/L), and total cholesterol (measured in mmol/L), all of which were collected at the same time as the VA data. All the variables used in the paper are detailed in Supplementary Table 1 in the data supplement. Baseline measurements of hypertension, diabetes, depression, and Townsend deprivation indices were also considered as covariates in the exploration of the association between VA and ASCVD.

Statistical Analysis

Data to describe baseline participant information was expressed descriptively, with mean and standard deviation (SD) describing continuous variables and frequency and percentages to describe categorical variables. Baseline characteristics across VA tertiles were compared using ANOVA for continuous variables and Chi-square tests for categorical variables. P-values represent overall differences among the three groups.

The association between baseline VA and incident ASCVD was estimated by Cox proportional hazards regression models. The first model adjusted for baseline measurements of age and gender, while the second model additionally included baseline measurements of ethnicity, smoking status, Townsend index, education level, family history of ASCVD, physical activity level, and comorbidities (depression, diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia). Two sensitivity analyses were conducted to examine the robustness of these results. First, we excluded all incident ASCVD cases that occurred within the first two years of follow-up to minimize the potential for reverse causality. Second, we further adjusted for clinically relevant variables, including systolic and diastolic blood pressure, HbA1c levels, LDL, HDL, and total cholesterol, to ensure that the findings remained consistent under additional levels of adjustment.

We conducted mediation analysis using a four-way decomposition approach to estimate the direct and indirect effects of VA on ASCVD outcomes through potential mediators, including hypertension, diabetes, depression, and socioeconomic status (Townsend index). Specifically, we assessed mediation effects for the overall ASCVD outcome and for its two subcomponents, CHD and stroke, to better understand their unique pathways. Mediation analysis was performed using the ‘med4way’ command in STATA (24). This method decomposes the total effect (TE) into four components: controlled direct effect (CDE, the effect is neither due to the mediator nor exposure-mediator interactions), reference interaction (INTref, the effect is only from interaction), mediated interaction (INTmed, the effect from interaction is only active when mediation is present), and the pure indirect effect (PIE, the effect due to mediation alone). A Weibull distribution fitted the outcome (years of follow-up before incident ASCVD) with an accelerated failure time (AFT) and a logistic regression model for the mediator. The proportion mediated by each mediator was also calculated. To quantify the magnitude of mediation, the study estimated the proportion of the association mediated by mediators (PIE/TE). To address potential confounding, covariates such as age, sex, ethnicity, smoking status, education level, physical activity, and hyperlipidemia were included in the models, as these variables could influence both the exposure (VA) and the outcome (ASCVD). However, the mediator under analysis was not included as a covariate when evaluating its mediation effect to avoid over-adjustment bias and preserve the integrity of the causal pathway. In the primary mediation analysis, other mediators were included as covariates to control for their potential influence on the mediator-outcome relationship and to obtain more precise estimates of the indirect effects. To test the robustness of our findings, a sensitivity analysis was performed in which other mediators were excluded as covariates. For each subcomponent (CHD and stroke), we evaluated the indirect effects of mediators using the same approach as for the overall ASCVD analysis.

Data analyses were conducted using Stata version 16 (StataCorp), and all P-values were 2-sided with statistical significance set at <0.05.

Results

Of the 502,395 UK Biobank participants enrolled between 2006 and 2010, VA was measured in 117,218 (23.33%) participants. After excluding participants diagnosed with ASCVD prior to baseline assessment (n = 6,696), a total of 110,522 participants were included in the final analysis (55.53% females; mean age 56.55 [8.12] years). Table 1 describes baseline characteristics for included participants stratified by VA tertiles. Compared to those in the lowest tertile of VA (the highest visual acuity level), individuals with lower visual acuity were older, more likely to be women, had lower educational qualifications, higher area deprivation, and were more likely to be current smokers. They were also more likely to have a family history of ASCVD and a history of systemic diseases (hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, or depression). Additionally, individuals in the lowest VA tertile had higher systolic and diastolic blood pressure, HbA1c, HDL, triglyceride, and total cholesterol levels (all P < 0.05, representing overall differences across tertiles).

Table 1

Cohort characteristics by VA tertile.

| CHARACTERISTIC | HIGHEST VA LEVEL (N = 39,168) | MIDDLE VA LEVEL (N = 36,130) | LOWEST VA LEVEL (N = 35,224) | P VALUE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), yrs | 54.17 (8.23) | 56.94 (7.92) | 58.81 (7.45) | <0.001 |

| Gender, No. (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Women | 19,840 (50.65) | 20,888 (57.81) | 20,772 (58.97) | |

| Men | 19,328 (49.35) | 15,242 (42.19) | 14,452 (41.03) | |

| Ethnicity, No. (%) | <0.001 | |||

| White | 35,442 (90.49) | 32,246 (89.25) | 30,653 (87.02) | |

| Non-white | 3,726 (9.51) | 3,884 (10.75) | 4,571 (12.98) | |

| Townsend index, mean (SD) | –1.18 (2.89) | –0.99 (2.98) | –0.69 (3.11) | 0.004 |

| Education level, No. (%) | <0.001 | |||

| College or university degree | 15,730 (40.16) | 12,665 (35.05) | 10,626 (30.18) | |

| Others | 23,438 (59.84) | 23,465 (64.95) | 24,598 (69.82) | |

| Smoking status, No. (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Never | 22,315 (57.24) | 20,197 (56.21) | 19,378 (55.52) | |

| Former/current | 16,667 (42.76) | 15,732 (43.79) | 15,527 (44.48) | |

| Family history of ASCVD, No. (%) | <0.001 | |||

| No | 18,880 (48.20) | 16,242 (44.95) | 15,477 (43.94) | |

| Yes | 20,288 (51.80) | 19,888 (55.05) | 19,747 (56.06) | |

| Physical activity, No. (%) | 0.062 | |||

| Not meeting recommendation | 5,576 (17.06) | 5,210 (17.75) | 4,902 (17.58) | |

| Meeting recommendation | 27,105 (82.94) | 24,147 (82.25) | 22,980 (82.42) | |

| History of diabetes, No. (%) | <0.001 | |||

| No | 37,449 (95.61) | 34,054 (94.25) | 32,517 (92.31) | |

| Yes | 1,719 (4.39) | 2,076 (5.75) | 2,707 (7.69) | |

| History of hypertension, No. (%) | <0.001 | |||

| No | 11,494 (29.35) | 9,430 (26.10) | 7,982 (22.66) | |

| Yes | 27,674 (70.65) | 26,700 (73.90) | 27,242 (77.34) | |

| History of hyperlipidemia, No. (%) | <0.001 | |||

| No | 23,500 (60.00) | 20,034 (55.45) | 18,294 (51.94) | |

| Yes | 15,668 (40.00) | 16,096 (44.55) | 16,930 (48.06) | |

| History of depression, No. (%) | <0.001 | |||

| No | 37,196 (94.97) | 34,105 (94.40) | 33,184 (94.21) | |

| Yes | 1,972 (5.03) | 2,025 (5.60) | 2,040 (5.79) | |

| Systolic blood pressure | 135.33 (17.72) | 137.49 (18.49) | 139.18 (18.75) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 81.81 (9.92) | 82.00 (10.02) | 82.22 (9.99) | <0.001 |

| HbA1c, mean (SD) | 35.33 (5.71) | 36.09 (6.36) | 36.89 (7.59) | <0.001 |

| LDL, mean (SD) | 3.57 (0.83) | 3.57 (0.85) | 3.57 (0.87) | 0.91 |

| HDL, mean (SD) | 1.46 (0.38) | 1.49 (0.39) | 1.49 (0.40) | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides, mean (SD) | 1.68 (0.99) | 1.68 (0.96) | 1.70 (0.98) | 0.001 |

| Cholesterol, mean (SD) | 5.71 (1.09) | 5.74 (1.12) | 5.74 (1.15) | <0.001 |

| LogMAR of visual acuity (better eye) | –0.18 (0.05) | –0.07 (0.26) | 0.13 (0.14) | <0.001 |

[i] Abbreviation: ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; LogMAR, logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution; HbA1c, Glycated Hemoglobin; LDL, Low-Density Lipoprotein; HDL, High-Density Lipoprotein.

Association of VA and Incident ASCVD

Over a median (interquartile range, IQR) follow-up duration of 11.10 (10.91–11.37) years, a total of 5,496 (4.97%) cases of incident ASCVD were documented. Baseline characteristics stratified by incident ASCVD are described in Supplementary Table 2. The incident ASCVD group was more likely to be older, male, and of non-white ethnicity than the non-ASCVD group. They also had a higher proportion of lower socioeconomic status, education attainment, and physical activity but higher rates of family history of ASCVD, smokers, depressives, diabetics, hypertensives, and hyperlipidemics. Furthermore, the incident ASCVD group had poorer VA than the normal group, especially in women (P < 0.001) (Supplementary Figure 2). A significant association between baseline VA and incident ASCVD was observed ([Hazard ratio (HR) = 1.97; 95% confidence interval (95%CI): 1.68–2.31, P < 0.001) after adjusting for age and gender. After multivariable adjustment, a one-line worse VA (0.1 logMAR increase) remained significantly associated with a 63% higher risk of incident ASCVD (95%CI: 1.35–1.96, P < 0.001). When dividing logMAR VA into low, moderate, and high tertiles, a significant dose-response relationship was observed between ASCVD risk and worsening VA across groups (P for trend <0.001). Similar trends emerged from the sex-stratified analyses (P for interaction = 0.867; female: HR = 1.46, 95%CI: 1.06–2.02, P = 0.020; male: HR = 1.73, 95%CI: 1.37–2.18, P < 0.001) (Table 2). Similar findings were observed after excluding participants diagnosed with ASCVD within the first two years of follow-up and further adjusting for clinically relevant variables (Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Table 4).

Table 2

Cox Proportional Hazards Models for Incident ASCVD by VA.

| MODEL 1 | MODEL 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P VALUE | HR (95% CI) | P VALUE | |

| Total analysis | ||||

| Visual acuity (Continuous variable, per 0.1 LogMAR) | 1.97 (1.68, 2.31) | <0.001 | 1.63 (1.35, 1.96) | <0.001 |

| Visual acuity (Categorical variable) | ||||

| T1 (highest visual acuity level) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| T2 (moderate visual acuity level) | 1.10 (1.03, 1.18) | 0.005 | 1.02 (0.94, 1.10) | 0.627 |

| T3 (lowest visual acuity level) | 1.30 (1.20, 1.37) | <0.001 | 1.17 (1.08, 1.26) | <0.001 |

| P for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Stratification analysis | ||||

| Stratified by gender | ||||

| Female | 1.93 (1.49, 2.51) | <0.001 | 1.46 (1.06, 2.02) | 0.020 |

| Male | 1.99 (1.62, 2.43) | <0.001 | 1.73 (1.37, 2.18) | <0.001 |

| Test for interaction | 0.725 | 0.771 | ||

[i] We used Cox proportional hazards regression for the incident ASCVD. Model 1 was adjusted for baseline measurements of age and gender. Model 2 additionally adjusted for risk factors shared between VA and ASCVD, measured at baseline, including ethnicity, smoking status, education level, Townsend index, family history of severe ASCVD, physical activity level, and comorbidities (depression, diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia).

T, tertiles of LogMAR value.

VA, visual acuity; ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; HR, hazard ratio; LogMAR, logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution.

Potential mediators of the association between VA and incident ASCVD

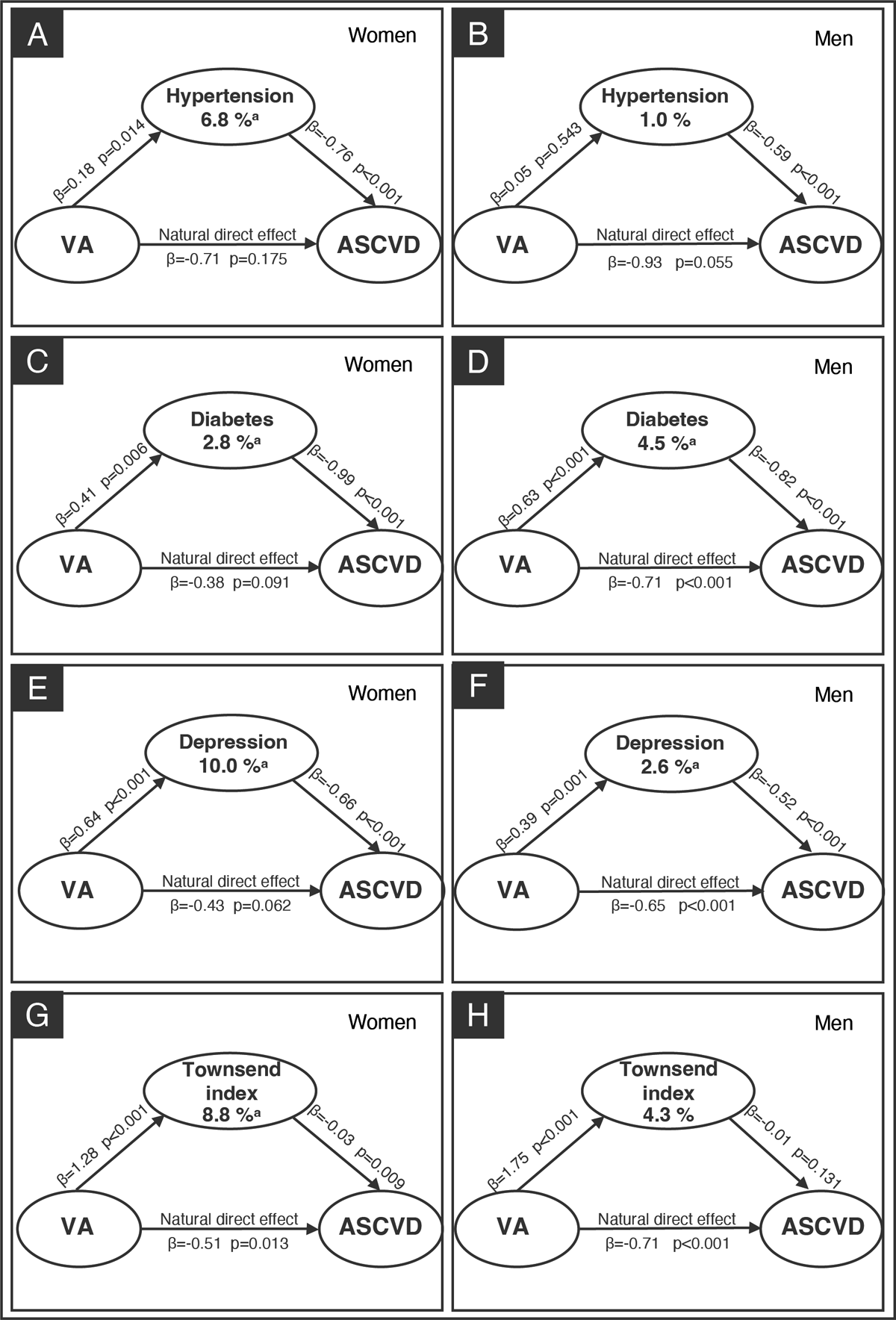

A mediation analysis assessed whether the association between VA and incident ASCVD was mediated through hypertension, diabetes, depression, and the Townsend deprivation index (Figure 1). In this analysis, hypertension (panel A), diabetes (panel B), depression (panel C), and Townsend index (panel D) explained 3.8%, 3.3%, 5.7%, and 5.9% of the estimated effects of VA on incident ASCVD, respectively (all P for indirect effect <0.05), after adjusting for all confounders. We repeated the mediation analyses stratified by sex and found that among women, hypertension, diabetes, depression, and Townsend index mediated 6.8%, 2.8%, 10.0%, and 8.8% of the indirect association between VA and ASCVD, respectively (all P for indirect effect <0.05). Among men, diabetes and depression made up 4.5% and 2.6% of the association between VA and ASCVD, respectively (all P for indirect effect <0.05). Hypertension and Townsend deprivation index were not significant mediators among men (Figure 2). Further details on the mediation analysis are provided in Supplementary Table 5. The results of sensitive analyses remained consistent with the primary analysis, demonstrating that the indirect effects of the mediators were not significantly influenced by the inclusion or exclusion of additional mediators (Supplementary Table 6). An additional analysis evaluated the mediating effect of VA on the incidence of ASCVD by event type (CHD and stroke). The magnitude of the mediation effect was highest in the VA-Stroke group, with hypertension, diabetes, depression, and the Townsend deprivation index explaining 27.9%, 4.3%, 6.9%, and 15.7% of the association, respectively, compared to the VA-CHD group (3.8%, 3.6%, 6.0%, and 7.0%, respectively) (all P for indirect effect <0.05) (Supplementary Figure 3).

Figure 1

Mediation analysis for VA and ASCVD. Mediation analyses were performed for hypertension (panel A), diabetes (panel B), depression (panel C), and Townsend index (panel D) separately. Apart from the mediator being analyzed, other mediators were included as covariates to account for their potential influence on the mediator-outcome relationship. Additionally, the analysis adjusted for baseline measurements of age, gender, ethnicity, smoking status, education level, Townsend index, family history of severe ASCVD, physical activity level, and hyperlipidemia.

aP for indirect effect <0.05.

VA, visual acuity; ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

Figure 2

Mediation analysis of sex-specific for VA and ASCVD. For women, mediation analyses were performed for hypertension (panel A), diabetes (panel C), depression disorder (panel E) and Townsend index (panel G) separately. For men, mediation analyses were performed for hypertension (panel B), diabetes (panel D), depression (panel F), and Townsend index (panel H) separately. Apart from the mediator being analyzed, other mediators were included as covariates to account for their potential influence on the mediator-outcome relationship. Additionally, the analysis adjusted for baseline measurements of age, gender, ethnicity, smoking status, education level, Townsend index, family history of severe ASCVD, physical activity level, and hyperlipidemia.

aP for indirect effect <0.05.

VA, visual acuity; ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

Discussion

In a large population of middle-aged and older adults, our study demonstrates that visual decline is associated with incident ASCVD, with a clear trend observed between the severity of visual decline and the risk of incident ASCVD. Furthermore, we provide evidence that several shared risk factors for both VA and ASCVD likely mediate this association. In particular, hypertension, diabetes, depression, and Townsend deprivation index influenced 3.8%, 3.3%, 5.7%, and 5.9% of this association, respectively. When analyzed by gender subgroups, the largest indirect association was observed for depression (10.0%) among women and diabetes (4.5%) among men.

Our findings suggest that declines in VA confer an increased risk for incident cardiovascular diseases. This is consistent with Thiagarajan et al. (25), who discovered in UK subjects 75 years and older that VI without ocular disease was associated with a small but significant increase in all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality. Another large cohort study of young and middle-aged Koreans demonstrated that VI was significantly associated with an increased risk of all-cause, injury-related, and cardiovascular mortality (26). Moreover, Lee et al. (27) showed in an American cohort that women, but not men, with severe bilateral self-reported VI were at significantly increased risk of cardiovascular mortality compared to those with no VI in fully adjusted models. While VI has been the subject of many studies, none so far have assessed the full spectrum of VA and incident ASCVD like the current research. Our analysis shows a positive independent association was pronounced in women and men across the VA spectrum. Therefore, visual decline should alert practitioners to potential vascular dysfunction and present an opportunity for the assessment of ASCVD risk factors.

Our analysis provides a better understanding of the mechanisms connecting VA to ASCVD, specifically hypertension, diabetes, depression, and Townsend deprivation index, which were identified as indirect mediators in the observed associations. Although these are well-known risk factors for both VA and ASVD, this is the first study to document that they mediate the precipitation of adverse health events through an association with VA. Ocular complications of systemic diseases, such as glaucoma associated with hypertension and diabetic retinopathy related to diabetes, are known to be indicators of longstanding risk factors for ASCVD and cause irreversible VI (28). More surprisingly, depression and socioeconomic status accounted for much higher mediatory effects than hypertension and diabetes in the VA-ASCVD relationship, even though hypertension and diabetes are traditionally among the highest risk factors for ASCVD events (2930). In fact, clinical practice guidelines suggest people living with mental health problems should be considered disadvantaged from their higher CVD risk (31). This is particularly relevant for individuals with VI, who are at a higher risk of developing depression due to reduced quality of life, social isolation, and decreased physical activity, further compounding their vulnerability to adverse cardiovascular outcomes (323334). Incorporating mental health assessments and interventions into routine care for visually impaired individuals could play a pivotal role in reducing the compounding effects of mental health issues on vascular health. Socioeconomic status significantly limits access to healthcare resources, which increases ASCVD risk through mechanisms such as long-term uncorrected VI, delayed diagnosis and treatment, and poorer vision-targeted health-related quality of life (3536). Studies have shown that individuals with lower socioeconomic status are less likely to receive timely and adequate eye care, exacerbating preventable VI and its associated health risks (37). Socioeconomic inequalities significantly contribute to disparities in cardiovascular outcomes, including higher rates of ASCVD events among lower-income groups (38). This highlights the need for equitable healthcare systems to ensure socioeconomic status is not a barrier to quality medical and eye care, reducing health disparities. Traditional risk factors like hypertension and diabetes, while important, may not fully capture the risk profile for ASCVD in populations with VI. Integrating mental health and socioeconomic assessments into routine clinical practice could provide a more holistic approach to managing and mitigating ASCVD risk in visually impaired individuals.

Mediators of the VA-ASCVD association varied greatly across genders, with women appearing to bear a disproportionately higher burden of VA-ASCVD risk. The most prominent mediator in women was depression, accounting for 10.0% of the mediation effect, compared to diabetes in men, which accounted for 4.5%. Women are nearly twice as likely to suffer from an episode of depression as men (3940), and the association between depression duration and incident CVD is particularly strong in women (41). In contrast, men have a 61% higher likelihood of developing diabetes than women (4243), which may explain its stronger mediatory effect in men. Besides, the socioeconomic effect in this study also biased women (8.8%) more than men. A previous study indicated that women from low-income households had higher risk status, greater risk factor burden, and more prevalent coronary disease (44). Our findings suggest that women with lower vision are the vulnerable populations for disparities in ASCVD through a socioeconomic status mediation pathway. An integrated health approach addressing the impacts of socioeconomic status and gender on visual and cardiovascular health is vital for reducing disparities and improving the well-being of women with visual impairments.

This study highlights that mediators for VA-ASCVD associations were markedly different when analyzed separately for CHD and stroke. The VA-stroke association was profoundly influenced by indirect associations, notably hypertension (27.9%) and Townsend deprivation index (15.7%). Hypertension’s role as a key mediator aligns with a pooled analysis showing that blood pressure is the most significant risk factor for stroke, accounting for over two-thirds of the total risk (46). As this is the first study to examine the dominating effects of mediators on VA-ASCVD and its subcomponents, our findings emphasize the substantial risk of VA-stroke mediated by hypertension and socioeconomic status. These results highlight the need for targeted interventions, such as enhanced blood pressure control and policies addressing socioeconomic disparities, to mitigate stroke risk in populations with visual impairment.

Our study was based on a prospective, large cohort with long-term follow-up that followed a standardized protocol for ocular and in-person assessments. Moreover, the UK Biobank routinely updates health-related records to identify incident ASCVD, which allowed us to comprehensively and longitudinally examine the association between visual health and ASCVD and their mediators. These features strengthen the reliability of the data and the integrity of our findings; however, some limitations should be acknowledged. First, we cannot exclude selection and collider bias, as there were differences in the frequencies of the outcome (incident ASCVD), exposure (VA), and mediators (hypertension, diabetes status, depression, and Townsend deprivation index) of interest that were not eligible for the current analysis (47). Nevertheless, selection bias is unlikely to distort our results considerably, given our findings followed a dose-response relationship. Secondly, the UK Biobank is representative of a largely white first-world country, which inhibits these findings from being generalized to multi-ethnic populations and countries of dissimilar demographic status. In consideration, it would be ideal for these findings to be examined across ethnicities and geographic regions with marked differences.

Conclusion

In summary, our findings suggest the visual decline is associated with ASCVD independently, with hypertension, diabetes, depression and socioeconomic status partly explaining the association between VA and incident ASCVD in the UK Biobank cohort. Depression and socioeconomic status had a stronger mediation effect than traditional factors like hypertension and diabetes. Taken together with a growing body of literature, our results suggest clinicians caring for adults with ASCVD and poorer vision should be aware depression and socioeconomic status are important mediators of ASCVD event risk, particularly in women.

Data Accessibility Statement

This project corresponds to UK Biobank application ID#86091. Data from the UK Biobank dataset are available at https://biobank.ndph.ox.ac.uk/ by application.

Additional File

The additional file for this article can be found as follows:

Supplementary Online Content

Supplemental data include 6 tables and 3 figures. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/gh.1406.s1

Abbreviations

VA, visual acuity; ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratios; ICD-10, the 10th edition of the WHO International Classification of Diseases; LogMAR, logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution; MHQ, mental health questionnaire; OR, odds ratio; SD, standard deviation.

Code Availability

STATA command med4way was used to perform causal mediation analysis with survival data (https://raw.githubusercontent.com/anddis/med4way/master/).

Ethics and Consent

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. UK Biobank has ethical approval from the North West Multi-centre Research Ethics Committee (11/NW/0382).

No patients were involved in setting the research question or the outcome measures, nor were they involved in developing plans for design or implementation of the study. No patients were asked to advise on interpretation or writing up of results. There are no plans to disseminate the results of the research to study participants or the relevant patient community.

Funding Information

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U24A20707, 82271125, 82171075, 82301260), the Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou (202206010092), the launch fund of Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital for NSFC (8217040546, 8217040449, 8227040339, 8220040257), Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation of Guangdong Province (2023B1515120028), Brolucizumab Efficacy and Safety Single-Arm Descriptive Trial in Patients with Persistent Diabetic Macular Edema (BEST) (2024-29), the Medical Scientific Research Foundation of Guangdong Province (A2021378), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation under Grant (2024T170185).

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Author Contributions

Study concept and design: Du ZJ, Hu YJ, Yang XH, Yu HH.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation: Du ZJ, Zhang XY, Shang XW, Bulloch G, Zhang F, Huang Y, Wang YX, Wu GR, Liang YY.

Drafting of the manuscript: Du ZJ, Zhang XY, Bulloch G.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Zhu ZT, Hu YJ, Yang XH, Yu HH.

Statistical analysis: Du ZJ, Zhang XY, Shang XW.

Obtained funding: Yu HH, Yang XH, Zhu ZT.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Hu YJ, Yang XH, Yu HH.

Study supervision: Hu YJ, Yang XH, Yu HH.

Zijing Du and Xiayin Zhang contributed equally.

Zhuoting Zhu and Xianwen Shang are co-senior authors.