1. Introduction

1.1 Background: FAIR (meta)data and research data management

Why should research data be findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable (FAIR)? The central asset of scientific work and progress is research data—here, specifically all digital data that is used or produced in the research process or is its result—and the metadata describing its context, genesis, provenance, and relations (‘data about data’). In a nutshell, results need to be reproducible for validation, and data needs to be reusable for further resource-efficient and cost-effective exploration (Bowers et al., 2023). Data is only reusable and will be cited more often (Piwowar and Vision, 2013) when it is also findable, accessible, and interoperable as summarized in the FAIR principles (Wilkinson et al., 2016). Reproducibility and FAIRness of data and its associated metadata are central goals of Research Data Management (RDM) and foundational to researchers’ success (Markowetz, 2015).

What is RDM and why do we care? RDM is part of Good Research Practice and describes the proactive and ongoing management and handling of research (meta)data throughout its life cycle, with the aim that data remains usable for the long term and independent of its creators. RDM considerations span every stage of a project—from initial planning, organizing, and documenting to storing, sharing, publishing, and preserving research (meta)data. Efficient RDM leads to labeled, tidy, and well-described data, easy to find files, reduced risk of (meta)data loss, and reduced time to navigate even foreign project data in a human-friendly as well as machine-readable way. To say it with Kanza and Knight (2022): ‘Behind every great research project is great data management’.

1.2 The challenges of data organization

One of the first, easiest, and most effective RDM measures is the conscious organization of (meta)data files using naming schemes and sorting them into a suitable folder structure. Considering which folder structure to follow and how to label for most effective navigation is a critical step at the project start, since retroactive rearranging of files and folders is time consuming, error-prone, and potentially confusing. Often, researchers go through trial and error in data organization, spending years with an ineffective system and finding themselves stuck, with too little time and overview to restructure their research outputs. Especially junior researchers lack experience regarding the requirements and difficulties of data and file organization, aggravating the challenge of drafting a sustainable folder structure.

1.3 Folder structure templates (FSTs) ease data organization but many templates are not comprehensive

Overcoming the challenge of data organization is best supported not only with (theoretical) advice, for example, Wilson et al.’s (2017) paper on ‘good enough’ practices, Briney’s (2020) worksheet for file naming, the 5S-Method (Lang et al., 2021), the CESSDA data management expert guide (CESSDA Training Team, 2020), and the RDMkit (RDMkit, 2025), but also with ready-made folder structure templates (FSTs). For individual research projects, there are a few options, like the folder structure by Nikola Vukovic (n.d.), and a data science-oriented template by Barbara Vreede (2020) based on the Cookiecutter project template (Krapp, 2017). Considering industry-derived templates can be worthwhile [e.g., Data Science Project Folder Structure (Rogonondo, 2025)], but potentially needs adaptation to research requirements. These templates have in common that they focus on a single project or experiment, covering elements such as datasets, documentation (but without templates for documentation), methods, and data visualization.

Existing single-project FSTs do not sufficiently cover research with the more extensive organizational requirements of a PhD project. A PhD (in the natural/life sciences) usually not only consists of multiple (side-)projects, but additionally requires subfolders to store administrative paperwork, presentations for thesis committee meetings, literature collections, and other associated files. A comprehensive and fully functional doctoral working directory requires an overarching folder structure. To our knowledge, there are only two larger FST: the Gin Tonic project (Colomb, Arendt and Sehara, 2023) and a tool by Ties de Kok (2018), however with little guidance and not tailored to doctoral research. We address this niche here with a FST specifically designed for (junior) researchers starting their (thesis) projects.

1.4 Providing a comprehensive FST

This publication is aimed at PhD candidates and researchers of life and natural sciences seeking to improve their data management practices, as well as RDM professionals looking for a reference on data organization, particularly folder structure. We compiled best practices for creating a folder structure (see Sections ‘Best practices for creating a folder structure’ and ‘Four steps to create a folder structure’) and, following these, provide a ready-to-use FST enriched with guidance README files and documentation templates (described in Section ‘Our FST for research projects’ with notes on adoption in Section ‘Adopting the FST’). We discuss in which ways our FST supports the creation of FAIR data (Section ‘The FST supports the creation of FAIR metadata and data’) and where it is limited (Section ‘Limitations and alternatives’), conclude highlighting the benefits of our product (Section ‘Conclusion’), adding an outlook on how to further support researchers in their RDM (Section ‘Outlook’).

Our comprehensive FST including guidance and metadata README templates provides a kickstart to (junior) researchers’ data organization. The FST has been archived in Zenodo (Demerdash, Dockhorn and Wilbrandt, 2025).

2 Methods

2.1 Contributors

To realize our vision of a comprehensive folder structure template (FST) specific for PhD research projects, we formed a working group of three data stewards from different institutes within Germany. We combined our collective expertise in research, RDM, and RDM support (combined 12 years) in the life sciences to create a FST tailored to enhance individual RDM practices. The interest in our product was expressed by both senior and junior researchers as well as data stewards in personal communications (e.g., at conferences). Personal communication with researchers also guided our design but we refrained from a more formal involvement since no volunteer (group) was available for a complete review or trial implementation within our time frame. Our setup invites and aims to integrate feedback (see also Section ‘Outlook’) and the FST is generic, flexible, and modular to accommodate as many use cases as possible.

2.2 Working mode and scope decisions

The structure of our FST as well as the four steps we followed to build it (see Section ‘Best practices for creating a folder structure’) were developed during group meetings over the span of 1.5 years. All concepts and principles realized therein are a result of capturing our own research and research supporting experience, data steward tips, best practices of RDM, and selected sources. It is important to note that the FST is specifically designed for individual work and may require extensive adaptations to suit group working environments, where, for example, specific naming conventions and structuring hierarchies already exist. Future iterations of our framework will need to address this limitation to accommodate multi-user scenarios (see also Section ‘Outlook’).

Similarly, we decided to exclude considerations of data protection and storage of sensitive/personal data from our endeavor (see also Section ‘Limitations and alternatives’). Measures like using only secure servers and implementing access control do not directly influence the considerations and basic outline of a folder structure and we are confident all our laid out concepts are applicable. The information necessary to properly handle sensitive data, especially in concordance with GDPR, has been compiled elsewhere, for example in RDMkit (RDMkit, 2025, page on Data Security).

2.3 Additional features: READMEs and parser

We decided to enrich our FST with two additional README types (see Section ‘Our FST for research projects’), to support researchers with guidance and to encourage metadata recording with templates, respectively. To ensure human-readability and compatibility with various tools (discussed in Section ‘The FST supports the creation of FAIR metadata and data’), these READMEs are written in Markdown format, which allows rendering and parsing across different platforms. Guidance README files capture our experiences and RDM best practices. Metadata README templates conform to Dublin Core standards, which we recommend as a minimum for metadata recording. Additionally, we developed a parser (Dockhorn, 2025a) written in Python to convert our metadata README templates from Markdown to JSON format, enhancing interoperability and enabling the creation of a metadata catalog. Such a catalog can serve as a foundational element for future API implementations or extensions utilizing XML Schema.

2.4 Deposition, license, and availability

To consolidate and track versions of the FST and its accompanying files, we set up a GitHub repository. This repository allows for collaborative updates and serves as a central hub for sharing our work with the broader research community as well as to collect feedback for future improvements or spin-offs of the FST.

To enhance accessibility, we released the FST and the parser repositories on Zenodo, assigning a Digital Object Identifier (DOI) to facilitate citation. Both are made publicly available under the Creative Commons Zero (CC0) and/or Unlicense, promoting unrestricted use and sharing. The complete FST, including all documentation, guidance, and metadata README templates, and the parser can both be accessed at Zenodo (Demerdash, Dockhorn and Wilbrandt, 2025; Dockhorn, 2025a).

3 Results

Here, we describe the considered best practices and our consolidated four steps to create our and any folder structure. In the following sections, we present the general structure and contents of our FST and a few notes on adopting our FST.

3.1 Best practices for creating a folder structure

There is no single correct one-fits-all solution to file organization. However, there are best practices and tips that can guide the design of an effective system. Here, we focus on useability and understandability, for which we need to consider users, naming best practices, and ease of navigation.

Foremost, effective organization systems (comprising of file/folder naming schemes, folder structure, and respective documentation) need to be usable and understandable. Usability depends on how well the system aligns with the user’s workflow for generating knowledge and processing data. Only a well-aligned system invites the consistent directed deposition of new files, it needs to make sense in the day to day work. Understandability, enabling swift navigation and identifying a desired file, depends on how well it aligns with expectations toward names and arrangement. Since expectations can differ, supporting documentation (e.g., a README with abbreviations) is particularly required when sharing with others (or when revisiting after a long time). Thus, understandability and usability of an organizational system hinges upon structure and labels for navigation.

To design a structure, it is important to consider the needs and expectations of everyone who has access, which existing structures need to be incorporated, how projects and collaborations are organized, how data and metadata are managed, and what is needed for effective reporting. Additionally, seeking feedback from colleagues on navigation ease can help optimize the folder structure, ideally before any data is entered.

Labeling or naming folders follows generally the same best practices as file naming (Briney, 2020). Shortly summarized: folder names should be descriptive, concise, consist only of alphanumeric characters, and if a date is included it should be formatted according to ISO 8601 (International Organization for Standardization, 2019, i.e., YYYY-MM-DD or YYYYMMDD). To keep folders in an order that corresponds to workflow instead of actual names one can use either a date for chronological sorting or a numerical ID with leading zeroes for numerical sorting. An advanced use (not implemented here) of numerical IDs for organizing folders is proposed in the ‘Johnny Decimal’ system (Noble and Butcher, 2025).

Navigating folders requires that their names provide enough information to determine whether they should be opened. Descriptive folder names, therefore, should accurately reflect the contents and relevant metadata on a more general and abstract level. This can include project relation, methodology, organism and related information, cell type, and other features of the contents. Often, names/initials of researchers are not required in a folder name; while it can help when a folder is shared or contains work by others, it is better practice to include this information in an accompanying metadata file.

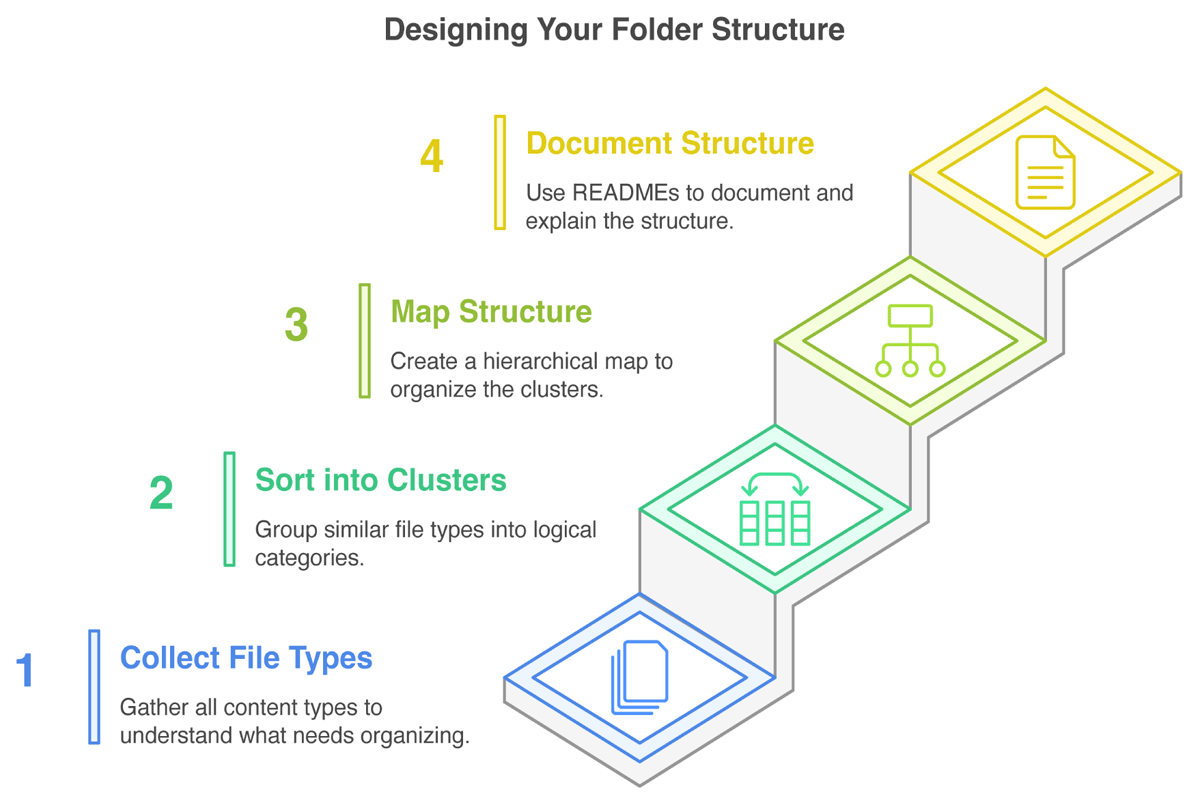

In summary, a usable and understandable folder structure considers and ideally plans for the needs and workflows of users, is well labeled and described, and thus conducive to collaborative work. The steps necessary to build a structure according to these requirements may not be obvious. Thus, we consolidated commonly known best practices to design the folder structure template (FST) itself into the following four steps (Figure 1), accompanied by three additional tips directed at researchers. We applied the same four steps to design the FST presented in results section.

Figure 1

An overview of the four step process for creating a folder structure for a research project.

3.2 Four steps to create a folder structure

How do we get from theory to a practical folder structure? In this section, we describe our approach and relevant considerations to creating a folder structure according to anticipated file contents, workflows, and general understandability. It consists of four steps (Figure 1), namely (1) getting an overview (collecting) of file types; (2) sorting the file types into logical clusters; (3) creating a hierarchy between clusters, that is, mapping the structure; and lastly (4) documenting the structure and its naming schemes. After these four steps we include three tips to further enhance working with folder structures, specifically, (1) adding a dormant (zzz) folder; (2) adding an ‘inbox’ (z_ext) folder; and (3) making it a habit to keep up the organization. These steps and tips can be applied on any scale, from single experiment to multi-project lab work.

Step 1: Collect your file (content) types

Identify the types of files you work with now and presumably in the future. Consider not only experimental data, but also documentation, presentations, illustrations, and other relevant resources, including any files you may generate or use during your research. Count in versions of various types as well as files you might receive from external sources. Think broadly about the data inputs and outputs needed for your research project, including raw data, processed data, code, methodology documentation, and other background information. Types can also be identified by considering file formats, like .pdf and .xlsx, but it is recommended to be more specific and include their content. You can collect file types on individual paper snippets to ease the following steps.

Step 2: Sort types into logical clusters

The identified file types will now be grouped. For this, build clusters of logically related file types. Clustering can result from content relationships, workflow progression or stages, etc. Identify major groups first and think about the most intuitive way to categorize files and contents for both you and others under consideration of relevant categories. For example, a ‘RNA sequencing’ cluster is close to the methodologically related types ‘organism genomes’ and ‘read counts’ but not ‘proteomics protocols’, while a cluster ‘communication’ is adjacent to ‘illustrations’ and ‘emails’ if they are often used together in collaborative workflows.

Step 3: Map hierarchical structure

To identify the most useful hierarchy for your work, determine the most important attributes of the contained file types/clusters. Importance depends here both on your workflow, that is, considering incoming files and how they are processed or accessed, but also on cluster size as well as on how you search for a folder/file. The relative importance governs which clusters/attribute categories are top-level folders. For example, if you take microscopic images of multiple organisms on multiple dates, you have to decide which information is of higher priority: is the parent folder ‘organism’ and contains subfolders for each ‘date’, or rather, does the parent folder ‘date’ contain subfolders for each ‘organism’? Contained subfolders should not repeat information or overlap in categories. Overlapping categories will lead to confusion if it is not clear enough where to put a file or search for it. Consider examples to test whether categories are clear enough. The principle of ‘one project, one folder’ is a helpful starting point, with subfolders organized to reflect the project design and workflow.

Keep folders from becoming too large, that is, containing many files and/or subfolders. If the list of folder contents exceeds your screen, navigation becomes tedious with scrolling. Also avoid deep folder hierarchies, that is, many folders (>6) nested within each other with little other content. This can lead to extensive navigation to get to the bottom, and to overly long paths. If you exceed the maximum path length of your operating system (e.g., 255 characters in Windows, Microsoft, 2024), it is possible that files are not saved or names are truncated. In this case, return to step 2 to reconsider your clustering.

Once you have outlined your complete folder tree [e.g., on paper, as empty folders, or using the online ASCII tree generator (Text Tree Generator, 2025) for visualization and documentation in one step], it is advisable to ask a colleague for feedback: is the structure understandable, does it make sense for the project you are planning, and are there experiences that speak for or against parts of the system?

Step 4: Document your structure with READMEs

Clear documentation is essential for maintaining and imparting an organized folder structure. We recommend README files (Dockhorn, 2025b) to provide easily accessible information about the structure’s layout, contents of each folder, project metadata, used abbreviations, and the general naming scheme. Keep a record of where to find data-related information and update README files as new data are added. This practice ensures that information is readily available and promotes continuity in the research process. For an example of such documentation with best practice file and folder naming, check the file naming documentation provided with our template file ‘M_NamingSchemes.md’; note that this file is intended for you to incrementally populate with your own schemes.

Additional Tips

Dormant folder: Consider adding archive folders wherever it seems sensible (suggested name: ‘zzz’, sorts last and invokes a ‘sleeping’ association for dormant data). There, you can store for example obsolete versions of a manuscript, which is especially helpful if you are doing manual versioning. Additionally, zzz-folders help to only keep current versions in sight instead of cluttering the view with older files; they can theoretically be deleted without losing actual work. Similarly, you can add temporary folders (‘tmp’) to store unsorted (test) data which can be deleted after some time. Tmp-folders can require more attention to maintain clear order, though.

Inbox folder: When you anticipate receiving many files from external sources that usually do not fit your file naming scheme, you can create a specific folder ‘z_ext’ (‘z’ for sorting last, ‘ext’ for ‘external’) as a first collecting place. Make sure to have a documented standard procedure in place to ingest such files into your system that you execute regularly. This routine should include that you note the following information in a dedicated location: (a) source, (b) access rights, (c) content of each incoming file/data set, (d) how it is renamed, and (e) where it is ultimately stored.

Habitual clean-up: Make maintaining organization a habit and incorporate file organization into your regular work routine. Ideally, each new file is placed in its correct folder immediately after creation. Set aside time for clean-up to prevent the buildup of disorganized files and thus save time in the long run—organizing a giant hay stack in one go takes more time and energy than picking up a few straws every day. An additional maintenance time-saver is keeping (zipped) empty folder structures, potentially with empty template files inside, to unpack whenever a new folder of this type is required (e.g., for presentations); this is implemented in our FST.

3.3 Our FST for research projects

Getting started with data organization remains one of the most challenging aspects when beginning research projects, especially a PhD. Often, the project parts, workflows of data acquisition, and methods of analysis are not clearly laid out initially. We developed our comprehensive FST to address this challenge by integrating ideas from single-project templates, following RDM best practices including our four-step method and the additional tips, and incorporating our personal experiences as well as experiences shared by our colleagues, both researchers and data stewards, to guide the design.

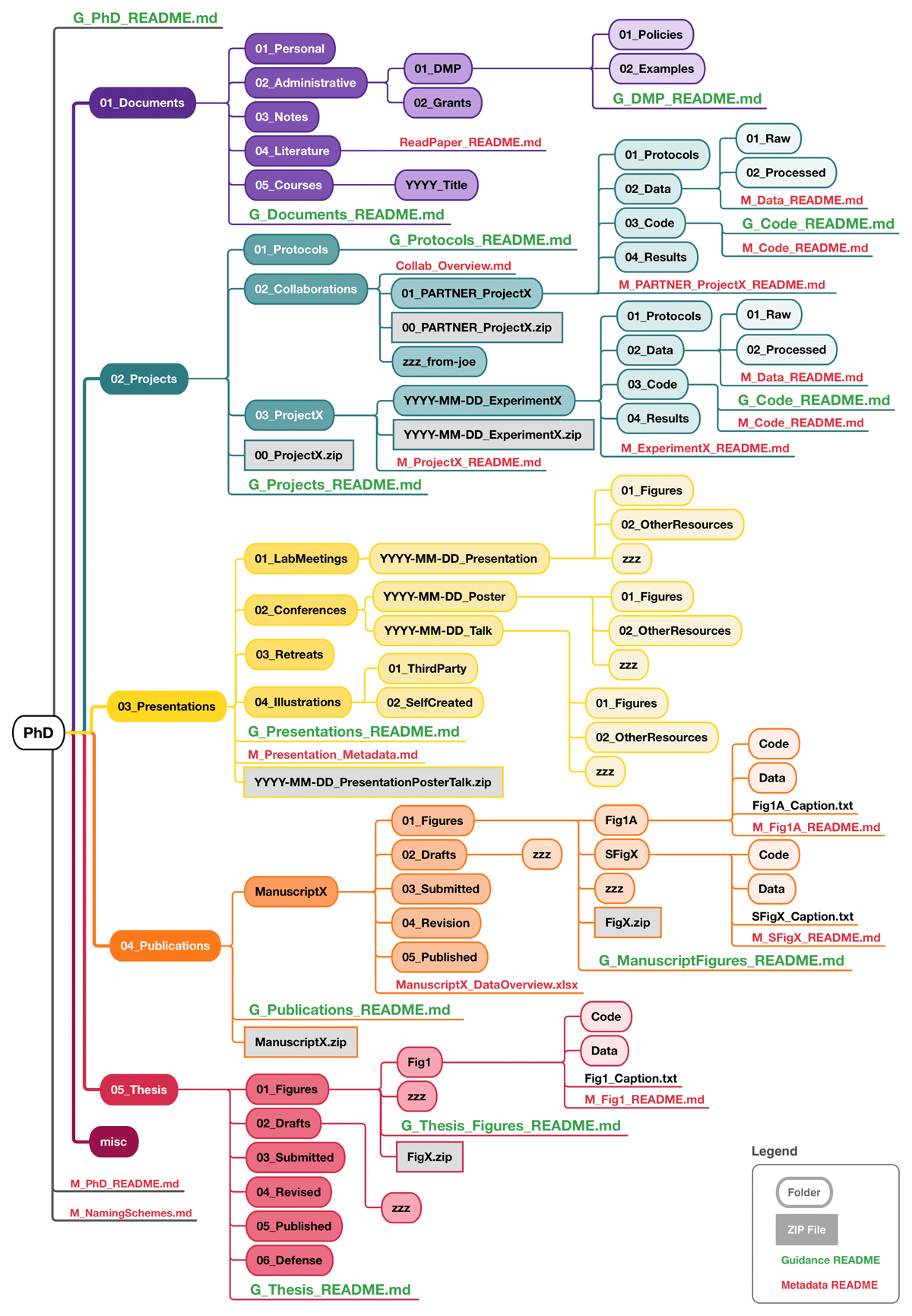

In the following, we explain the applied conventions and shortly describe the (anticipated) content and purpose of the five main folders of our FST and its included guidance and metadata README templates, The main folders separate content into (1) (general/administrative) documents, (2) projects, (3) publications, (4) presentations, and (5) thesis contents.

The structure of the FST (Figure 2) as well as the naming scheme are designed to follow principles of logical grouping and sorting (by prepending folder names with two-digit numbers, since the alphabetic sorting of pure folder names does not necessarily reflect workflows or accessibility considerations), chronological order [with prepended dates in ISO, 8601 YYYY-MM-DD format (International Organization for Standardization, 2019)], ease of navigation, and to ensure nothing is lost or scattered. They were created to accommodate all research files of researchers of any stage or discipline (with a strong focus on junior researchers in the natural/life sciences).

Figure 2

An overview of the folder structure template (FST) presented here.

In addition to the FST, we provide guidance README files (‘G_*_README.md’) and metadata recording templates (‘M_*_README.md’) in a plain text human-readable Markdown format to support not only the implementation but also upholding a useful and understandable folder structure. Guidance README files are provided for each top-level folder of our FST; they briefly document and describe the content and recommend best practices of the respective area of work. Metadata README templates are located in data-storing subfolders; they prompt structured documentation of the respective data following minimal requirements of the general metadata standard Dublin Core (DCMI, 2025a). Metadata README templates as well as subfolder structures that we anticipate being required in multiple copies are provided additionally outside of the FST for quick access.

The five top-level folders are shortly explained below, with detailed descriptions available in the main README on GitHub (‘G_PhD_README.md’) and in the respective guidance READMEs of each top-level folder.

1. Documents

Researchers generate and manage various important documents in addition to experimental results, including for example business trip forms, grant proposals, meeting notes, personal–professional documents like a CV and course certificates, administrative paperwork, and literature. Furthermore, It is important to familiarize yourself with the data management policies of your funding organizations and institute, so saving these documents for quick access is sensible. Additionally, we recommend to write your own data management plan (DMP) (Schwab et al., 2022; Science Europe, 2021) which can also be added to the respective ‘DMP’-subfolder for easy reference. Notes (Schreier, Wilson and Resnik, 2006), especially meeting notes, whether saved as text files; exported from a note-taking app; or scanned from handwritten notes, are relevant research records and need be stored securely as well.

To organize these materials, the ‘Documents’ folder is divided into five subfolders: ‘Personal’, ‘Administrative’ (incl. ‘DMP’), ‘Notes’, ‘Literature’, and ‘Courses’.

2. Projects

This folder captures generative research, including data collection and creation. We anticipate that this is your main working area, containing ‘hot’, actively used data.

This folder contains three key subfolders. The first is the ‘Protocols’ folder, intended for frequently used protocols or procedures that you often repeat for multiple projects, making them easily accessible. While we recommend using an Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN) for storing all wet-lab protocols, this folder can serve as a personal backup location for saving exported ELN protocols. Collaborative work finds a home in the ‘Collaborations’ folder. Within this folder you find project subfolders that are arranged the same as in the next folder, ‘ProjectX’.

The ‘ProjectX’ folder operates on a ‘one project, one folder’ principle, with subfolders organized by experiments. ‘Experiments’ can also be understood and renamed as method, test, or hypothesis, etc., depending on your workflow. Here, we assume that each work package or question of a PhD thesis counts as a project, and each project entails multiple experiments to investigate the respective question. The ‘X’ in the folder name is supposed to be replaced by a more meaningful indicator, especially when project-subfolders are created.

Each experiment subfolder in ‘Collaborations’ and ‘ProjectX’ is labeled with a date (a placeholder in the template) and a descriptor. It includes its own ‘Protocols’ folder to store experiment-specific protocols, while avoiding overlap with the general protocols. Within each experiment’s subfolder, there is a place for ‘Data’; which is further divided into ‘Raw’ and ‘Processed’, ‘Code’, and ‘Results’. Raw data should contain output of your instruments, software, or unmodified recordings of measurements; ideally, this output is stored with ‘read-only’ access rights to remain unaltered (Borer et al., 2009). Processed data that has been saved in another format, transformed, cleaned, or aggregated for better interpretation belongs in the ‘Processed’ folder. If you use Microsoft Excel for analysis, place those files in the ‘Processed’ subfolder. For analyses done with Python or R notebooks, store the script/markdown files in the ‘Code’ folder, which should mirror your directory structure on GitHub or GitLab if you have one. Finally, the ‘Results’ folder is for saving the output of analyses, such as figures, summary statistics, and PDF reports.

3. Presentations

A significant part of working in academia involves presenting approaches and data at ‘LabMeetings’, ‘Conferences’, and ‘Retreats’. Maintaining separate folders, as suggested here, for these occasions helps to locate material for the next presentation or slides to share with another researcher. An additional subfolder is reserved for illustrations, separated into ‘ThirdParty’ and ‘SelfCreated’; building a personal repository of helpful illustrations (including their source and license) can speed up presentation preparation.

4. Publications

The ‘Publications’ folder collects manuscripts (and potentially other written research output) in individual subfolders. One such subfolder template is included to help organize manuscript files for submission.

Assuming that you work on ‘hot’ data to create figures in the ‘Projects’ folder, we recommend that you store ‘colder’ (semi) final figure/table versions here. To maintain a data lineage, we suggest that you either copy the data excerpt you visualized here or, if the underlying data file is too large, reference the location (in ‘Projects’) and file version with a metadata README template next to the figure. Additionally, it is good practice to store a copy of the code that generated the figure or a description of the respective method with the figure. Thus, each figure forms a reproducible entity with its underlying data and generation method. Data that is not part of a figure but publication relevant (raw or processed, e.g., genome sequences) and needs to be published alongside your article, should not be copied here, only referenced.

The ‘Drafts’ subfolder is intended to hold manuscript versions while you are working on them; this should include (dumps of) the related bibliography. This is to say, we recommend to store a list of references cited in the manuscript closeby. The BibTex format (Paperpile, 2022) is a good choice for reference lists, exporting to it is facilitated easiest by using a citation manager (see ‘G_Publications_README.md’ for more details). If you are using an external tool for writing such as Overleaf (2025), deposit at least significant versions here. Important versions should be saved and named carefully (e.g., with a prepended date); this can become important when the writing process needs to be substantiated in the case of an accusation of plagiarism or ghost writing (Wolkovich, 2024). Apart from this worst case scenario, it is also helpful to track your progress and be able to pull inspiration or phrases from earlier, potentially more expanded drafts.

The version submitted to the journal should be stored in the ‘Submitted’ subfolder. Additionally, it is sensible anticipate that your manuscript might need revision; thus, keep revised versions in the ‘Revision’ subfolder. The ‘Published’ subfolder helps to quickly find the actual last version.

5. Thesis

Analogous to the manuscript subfolders, and following the same principles as in ‘Publications’ above, the thesis-subfolders capture ‘Figures’, ‘Drafts’, and ‘Submitted’, ‘Revised’, and ‘Published’ versions. Additionally, there is the subfolder ‘Defense’ to hold, for example, the presentation and its script, background information for examination questions, and similar.

Creating a dedicated thesis folder already at the start of this journey is beneficial. As you progress through your PhD, you will come across many ideas and thoughts related to your thesis during discussions or while reading papers. It is important to document these ideas in a word document or text file as they arise. Organizing these notes and their sources by section—such as ideas for the introduction or discussion—can be very helpful. Eventually you will have a well-structured document that can serve as a strong foundation for your thesis.

3.4 Adopting the FST

Adopting, adjusting, and using the FST may seem like a big task, thus we provide a checklist (Supplementary File 1) and the following guiding words to break it down. Additionally, we encourage data stewards to promote the FST (also covered in the adoption checklist, Supplementary File 1).

How can researchers start to use our FST? As a first step, you will need to download the FST from Zenodo (Demerdash, Dockhorn and Wilbrandt, 2025) or the linked github repository. After unpacking the ‘PhD.zip’ file, we recommend to spend dedicated time to review its contents: familiarize yourself with the structure, read the guidance, and explore the metadata README templates. Consider your own existing data and workflow and, leveraging the four steps of folder structure creation (Figure 1), decide whether changes are required. Make sure to take data protection requirements into account (out of our scope, see Sections ‘Working mode and scope decisions’ and ‘Limitations and alternatives’) and that a backup routine is in place. These initial considerations, changes, and finally moving your files into the structure certainly take time, however, it is hard to estimate how much, as this depends on many individual and circumstantial factors. When transitioning your files into the folder structure, we recommend one of two approaches: either complete the process in one go, taking as much time as needed to start fresh, or gradually organize your existing files by working through one top-level folder at a time. In parallel, begin using the new template for any new files you create. If any questions or feedback arise along the way, we encourage you to reach out via github issue or email.

How can data stewards promote adoption? After understanding the FST and its features, data stewards can effectively recommend it to researchers, point them to the download links, and support them in adoption. Advertisement in the form of posters and talks or during onboarding as well as trainings and workshops are good promotional measures. We will continuously link relevant material to the resource as they are created, currently, two posters and two slide decks are linked at the FST Zenodo entry (Demerdash, Dockhorn and Wilbrandt, 2025). Contributions and feedback are welcome to enhance these available resources.

4 Discussion

Although comprehensive, we anticipate that the presented structure may not fit everyone and thus we encourage users to modify it following the above outlined best practices. For example, postdocs can adapt the folder structure template (FST) by omitting thesis-related folders. Changes may also be necessary when working in a group that has already set standards for data organization. For PhD candidates, it may become necessary to iteratively adapt the structure as their workflows emerge. In all these cases we advise to implement changes sooner rather than later to avoid double work, data loss, or other restructuring hazards. However, we are confident that the FST is useful as is and can provide a good overview of which general file types a junior researcher can expect to encounter. Additionally, contemplating, implementing, and maintaining good RDM habits, starting with file organization, is pivotal in creating FAIR metadata and data.

In the following sections we discuss how our FST can support the creation of FAIR metadata and data (Section ‘The FST supports the creation of FAIR metadata and data’), highlight the limitations of our structure and hierarchical structures in general and point to potential organizational alternatives (Section ‘Limitations and alternatives’), conclude with an appeal to the data steward community as well as researchers (Section ‘Conclusion’) and provide an outlook on further work, specifically a habit tracker to support researchers (Section ‘Outlook’).

4.1 The FST supports the creation of FAIR metadata and data

Achieving FAIR (meta)data (Wilkinson et al., 2016) is built upon a commitment to a well-organized folder structure, thorough documentation, and to best practices for file and folder names (Briney, 2020). Thus, using our FST, which follows RDM best practices, fundamentally supports the creation of findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable (FAIR) data. Specifically, the following features are relevant to support FAIR data production (Table 1) and described below: (1) the structure and its names; (2) the metadata README templates; (3) READMEs are in Markdown format; (4) readiness to increase machine-readability; and (5) the explicit publication folder.

Table 1

The FST supports the creation of (meta)data guided by the FAIR principles. For each of the four principles, the table shows the FST’s features supporting it.

| FAIR PRINCIPLE SUPPORTED… | … BY FEATURES OF THE FST |

|---|---|

| Findable | Comes with and supports the creation of intuitive and documented folder structure and naming scheme. Metadata README templates prompt sign-posting. |

| Accessible | Simple, software-independent folder system and parser with DOI acts as accessible publication example. Metadata README templates prompt the entry of contributor and license information. |

| Interoperable | All files are provided in Markdown format. Guidance on file formats supports the creation of readable and interoperable (meta)data fit for long-term archiving. |

| Reusable | Flexible metadata README templates enable immediate, structured metadata recording adaptable to any discipline. Metadata README templates and guidance READMEs encourage comprehensive documentation. All FST contents provide and thus encourage the provision of license information. |

The structure and its names

Findability and reusability require that data can be easily discovered by humans and machines. Even before a (meta)dataset can be uploaded to a database and receive a persistent identifier (PID), as required by the FAIR principles (Wilkinson et al., 2016), findability needs to be ensured. It starts with file and folder naming and organization, considering best practices to render names and structure understandable and intuitive for humans and interoperable for machines. This is the basis our FST provides. The FST, if kept as is, comes with metadata describing itself in the guidance READMEs. Here, folder structure and naming scheme are documented and thus further support findability for humans.

The metadata README templates

The metadata README templates accompanying our FST augment findability and reusability of data, both with their content and their format. The templates prompt the user to enter metadata immediately, following a minimal standard in analogy to the Dublin Core metadata schema (DCMI, 2025b) consisting of fifteen core elements (e.g., title, creator, relation). The templates are sectioned to attribute and describe each element and can easily be extended, for example to include more discipline-/method-specific metadata elements [e.g., species, see also Darwin Core (Biodiversity Information Standards (TDWG), 2025]; cf. ‘G_Projects_README.md’). The provision in sectioned Markdown (.md) format serves a balance between high read- and write-ability for humans without more specific knowledge, long-term accessibility, and rudimentary machine-readability for further processing (Dockhorn, 2025b), laying a minimal foundation of interoperability. The prompts for contributor information and licenses as part of access information support a minimum of accessibility in the FAIR sense. A recent, commendable Excel-based approach to record metadata (Seep et al., 2024) provides more comprehensive recording and guidance for biomedical research, at the cost of requiring proficiency and patience for Excel and reduced reading/writing ease.

READMEs in markdown format

Interoperability of both data and metadata largely hinges upon their file formats. This is not in itself induced by the presented FST, but the guidance README at the project level provides relevant best practice and further reading recommendations. Keeping an eye on file formats, especially in the context of long-term archiving, is an important aspect of good RDM (Borer et al., 2009). Similarly, creating interoperable file content, for example, tidy data in spreadsheets or columns following a given standard [e.g., in the General Feature Format (GFF) of genomics (EMBL-EBI, 2025)] is highly encouraged and bolstered by recommendations to be found in our guidance READMEs.

Ready to increase machine-readability

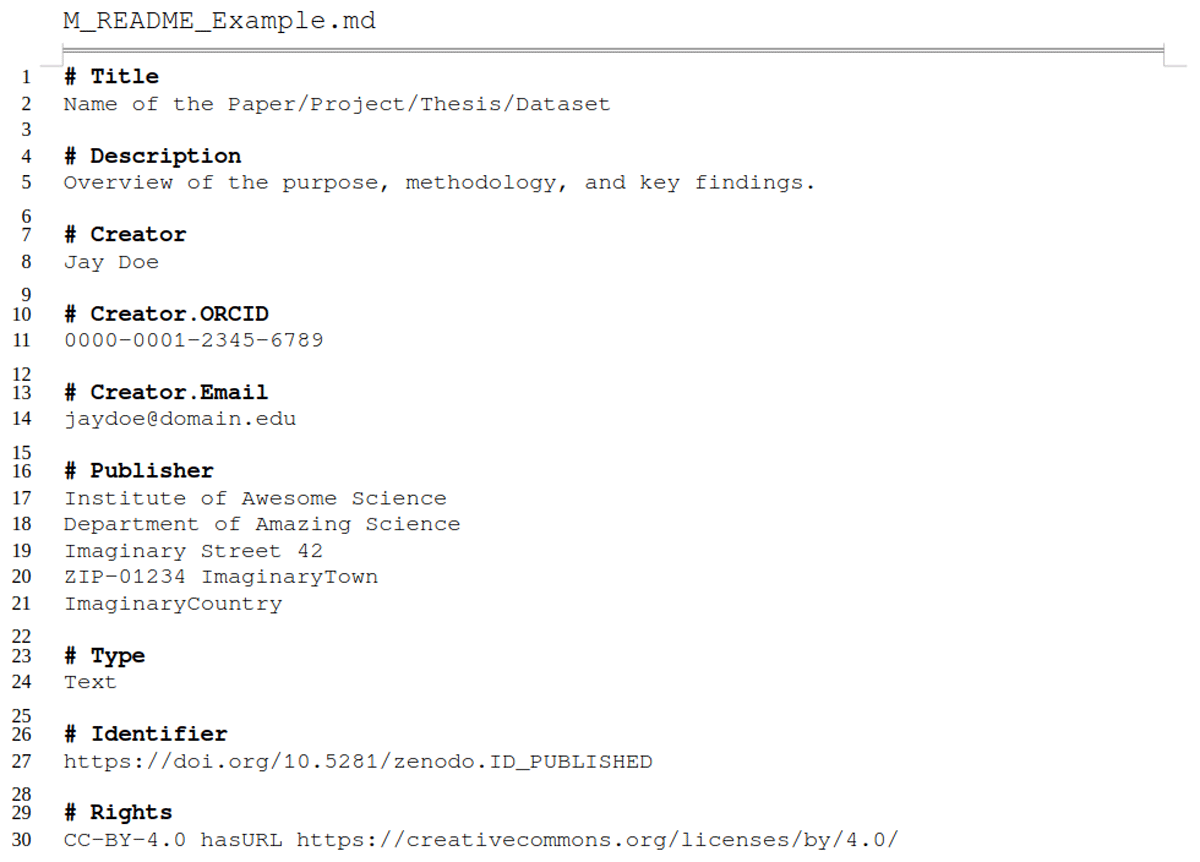

To further improve machine-readability and interoperability of metadata in markdown-style, a more structured format than ours would be necessary [e.g., YAML (2021) as used in headers of R markdowns; or JSON-LD (2025) as used by data management interfaces like YODA (Utrecht University, 2025)]. However, to produce and read such a format, a certain literacy in the respective language or an additional tool [e.g., DataCite Metadata Generator (Bayer et al., 2022)] is a prerequisite. We refrained from increasing machine-readability further to keep the required effort to get started with the metadata README templates as low as possible. We nevertheless encourage our reader to explore and implement machine-readable/-actionable data and metadata formats (Batista et al., 2022; Subramaniam et al., 2021) to increase findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability even more. A good starting point is to compare the exemplary metadata Markdown file provided in Listing 1 and Supplementary File 2 (also represented as YAML file in Supplementary File 3) or a ZENODO.JSON (CERN Data Centre, 2025) file, which provides structured and interoperable information with controlled vocabulary and relationships to other entities.

Listing 1

Exemplary (shortened) descriptive Markdown file for enriching metadata, designed for both human-readability and machine-friendly processing. The sections as well as the markup syntax facilitate the use of key-value pairs and support nested structures and relationship definitions.

We provide a simplistic parser (our metadata markdown to JSON) (Dockhorn, 2025a) as launch pad for this endeavor. This results in the possibility of transferring the associated data into a highly structured database solution, for example, NOMAD Oasis (Scheidgen et al., 2023) or Coscine (RWTH Aachen University, 2025), and making it accessible to other researchers.

The publication folder

Organizing data consciously and following the principles of ‘keep raw data raw’, ‘one project, one folder’, and ‘use meaningful names’ (Borer et al., 2009) helps not only to find and use files during the day to day work but also when preparing a data package for publication. We are convinced that making use of the publication folder in combination with mindful RDM fosters data publication: less time is needed to gather data and metadata, with structures and documentation already following best practices as demanded by leading repositories [e.g., PANGEA (Felden et al., 2023); DRYAD (Dryad, 2025), Zenodo (European Organization For Nuclear Research and OpenAIRE, 2025)]. We encourage data publication following the Open Science paradigm ‘as open as possible, as closed as necessary’ (Landi et al., 2020) to increase not only accessibility, but also visibility of research.

4.2 Limitations and alternatives

Limited focus on data protection

Working with sensitive or personal data requires additional technical measures for General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) compliance, which are beyond the scope of this paper (see also Section ‘Methods’). These measures depend on institutional policies and the technical and organizational measures (TOMs) in place, which should align with the type of data and the risk of re-identifying individuals. While the folder structuring principles and RDM best practices we presented still apply, they must be supported by secure storage, strict access controls, and specific documentation. Identifiable data should be stored in encrypted, access-restricted subfolders, separate from anonymized data, with de-identification steps clearly recorded. Sensitive data and pseudonyms must not be stored together. Researchers handling personal data—such as health or genomic information—should assess the sensitivity level of their data and implement appropriate technical safeguards in line with institutional and project-specific policies. Understanding the nuances, risks, and legal implications associated with sensitive data is essential and requires more information than we can provide here. A starting point may be the site by RDMkit (RDMkit, 2025) on Data Security.

Folder hierarchy limits the complexity of representable file relations

Our approach is designed to be as simple as possible, relying on folder structures as everyone knows them from file browsers and on plain text files everyone can open and interact with. This simplicity has the benefit of easy access, but it is also limiting due to being under-complex for conceivable cases. Thus, we also want to mention two ideas—aside from tagging (i.e., assigning keywords or markers to content)—that can be helpful for more complex file organization: knowledge graphs to interconnect files with multiple relations, and document management systems providing metadata enrichment and versioning.

Our FST relies on a clear hierarchy, implying that every file has one single location where it can be unambiguously placed. However, it is common that files are required in multiple instances, for example when using a specific standard operating procedure document in several experiments. Essentially, one can either build a deeper folder structure (our approach: leave the document at the top and add folders for every experiment; this will fail in more complex cases), copy the document to all experiment folders (redundant but explicit; can be problematic if the file is large and/or there are many locations and if changes need to appear in all instances), or use symbolic links (explicitly refer to a single file from multiple locations). Symbolic links are shortcuts pointing to files/folders in different locations and allow access without making a copy; this also means that changes to the original instance are immediately available everywhere, which can be undesirable if individual changes or versions need to be kept. Using this approach opens the hierarchical structure, so it is an unstructured graph pointing to files/folders, which cannot be organized in a linear relation anymore—instead a graphical representation would look like an (irregular) net, a knowledge graph. The downside of cross-referencing on different levels is a large potential for emerging chaos, for example, in loops and broken links. Also, most operating systems and cloud solutions prevent the archiving of symbolic links, which interferes with versioning and publication of datasets organized this way.

Alternative approaches to manage complex file relations

One possibility to circumvent the aforementioned challenges with symbolic links is to use a dedicated software, which supports linking and backlinking of local Markdown files. We encourage the reader to explore GUI-based note-taking software, for example, Obsidian (2025), Zettlr (2025), or Logseq (2025), to create your personal knowledge management resource and cultivate your ‘digital garden’ of RDM.

On the other hand, external software products such as document management systems [e.g., CKAN (Open Knowledge Foundation, 2025), Invenio (CERN & Contributors, 2025), DSpace (Lyrasis, 2024) or Dataverse (King, 2007)] store data/datasets in databases allowing enrichment with (user-defined) metadata, and provide built-in versioning control. Furthermore, persistent identifiers such as registered DOIs and Handles or even unique database-related URIs (uniform resource identifiers) support the findability and reusability of the resources. The downsides of these systems are typically the installation/maintenance of additional software, the unintuitive cluttering of files due to internal flat organization structure, and the high amount of storage redundancy due to versioning (especially in the case of rapidly accumulating raw datasets). Thus, these systems are more suitable for ready-to-publish and ready-to-archive documents instead of being a space for generative day to day work.

Approaches to distributed version control and collaboration

Software designed for distributed version control, such as git (Git community, 2025), can also be used for tracking file modifications and facilitate collaborative efforts using our FST. However, it is important to consider that these tools are mostly useful for text-based files rather than for binary/proprietary files, which often reside as raw datasets or document formats within the folders. Moreover, frequent modifications to ‘hot’ large files, particularly in the 02_Projects folder, can also lead to significant storage redundancy in the version history, creating a performance penalty for use. To address these challenges, one can either utilize dedicated software extensions to manage large files, which monitor files solely on the remote system, or save files in cloud storage while maintaining pointers as references in the repository independently. We encourage the reader to familiarize themselves with the concept of distributed versioning systems, which facilitate decentralized sharing and collaborative work.

In summary, we here aim to raise awareness that data protection requires special attention not covered in this publication, and that the hierarchical sorting of files in our FST may not fully reflect complex file relations—for which case we encourage the exploration of alternative file organization systems.

4.3 Conclusion

The folder structure template (FST) presented in this paper offers a practical solution to one of the challenges that life/natural science researchers, particularly doctoral candidates, are facing: data organization. A deluge of files from multiple sources, under-documented tinkering with methods, and a lack of file naming standards combined with little overview of the data generation and analysis workflow are often significant obstacles that can impede progress. By implementing a FST, researchers can organize their data and metadata more efficiently and according to best practices even with little to no prior knowledge. We provide a comprehensive FST that is accompanied by guidance READMEs and metadata README templates, to support researchers in the production of FAIR (Wilkinson et al., 2016) and reproducible data.

The FST and accompanying guidance were created with life science researchers in mind, but researchers from other disciplines can benefit from it as well. The FST is intended to be flexible, allowing users to adapt it to their developing or specific research needs and preferences while encouraging them to be methodical about it. The benefit of having a well thought out, human-intuitive, and documented structure to start data organization with is that it, just like other standards, is freeing. It frees time: habitually clearing up individual files is faster than to occasionally move scattered heaps of data; immediate documentation is quicker than retrograde fragment hunt. It also frees mental energy: we need to think less to come up with a sensible file name or the relevant metadata to record. In summary good RDM frees up resources and creativity, allowing us to focus more on research itself.

4.4 Outlook

Future developments of our FST

We strongly encourage researchers and data stewards to engage with the FST and provide feedback (e.g., via github issues); we look forward to incorporating suggestions to better match specific user needs, for example in the form of modules for certain data analysis workflows. As the FST is more and more adopted, as we hope, it will also become apparent which adaptions are necessary to provide a viable FST for multi-user settings.

We anticipate that the body of additional material such as slide decks, posters, and training material will grow, also from our past and future work. Collecting and linking the new material to the FST Zenodo entry (Demerdash, Dockhorn and Wilbrandt, 2025) will remain our ongoing project.

Habit tracker app idea

Good RDM benefits from being a habit, and habits are easier to maintain with a habit tracker. Habit trackers remind, visualize progress, create accountability, and improves adherence to goals while reducing stress. Thus, we propose the development of an RDM Habit Tracker app, designed to support and enhance RDM practices. Note, however, that using an additional app can also impose a burden on researchers, such as ‘one more thing to check’ and may feel like duplicating work (entering ‘I did this’ instead of just doing it). The benefits may outweigh such burdens, depending on the implementation and ease of use. In our ideal vision, this app would allow users to set goals and log their efforts, track the time they spend on various RDM activities, providing valuable data on their habits and time investment, while helping them identify areas for improvement. By integrating a Pomodoro timer, the app could promote focused work sessions, while an embedded customizable metadata worksheet would facilitate the export of information directly into README files, streamlining documentation processes. Additionally, the app could incorporate resources like RDMkit (RDMkit, 2025) and CESSDA (CESSDA Training Team, 2020) to offer best practice recommendations, feature a license chooser to aid in data sharing decisions, and interface with data management plan tools to inform the user and receive updates. A unique aspect of the app would be its ability to conduct a FAIRness test, linking the quality of RDM practices to the time spent on them, thereby encouraging efficient and responsible data management.

Glossary

API: application programming interface

CSV: comma-separated values

DMP: data management plan

DOI: digital object identifier

ELN: electronic lab notebook

FAIR: findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable

FST: folder structure template

GDPR: general data protection regulation

JSON: JavaScript object notation

JSON-LD: JSON for linked data

MD: MarkDown

PID: persistent identifier

RDM: research data management

TOM: technical and organizational measures

URI: uniform resource identifiers

XML: extensible markup language

YAML: YAML ain’t markup language

Data Accessibility Statement

The folder structure template (FST), metadata README templates, and best practices for Research Data Management (guidance READMEs), along with the Python-based metadata parser, are openly available. They can be accessed at the following Zenodo/github links (Demerdash, Dockhorn and Wilbrandt, 2025): https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15835125 and https://github.com/RDMJeanne/FolderStructure. The parser is available (Dockhorn, 2025a) at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14942696 and https://github.com/Bondoki/ParsingMetadataMD2JSON.

These resources are released under an open-source license to ensure long-term accessibility and reusability.

Additional Files

The additional files for this article can be found as follows:

Supplementary File 1

Checklists for adopting the FST for researchers and data stewards (PDF format). DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/dsj-2025-035.s1

Supplementary File 2

Metadata file example (Markdown format). DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/dsj-2025-035.s2

Supplementary File 3

Metadata file example (YAML format). Information content is the same as in Supplementary File 2, but allows comparison of the two representation formats. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/dsj-2025-035.s3

Acknowledgements

RD thanks the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) for its support through the Collaborative Research Center ‘Chemistry of Synthetic Two-Dimensional Materials’ (SFB-1415-417590517).

YD, RD, and JW thank the German and international networks of data stewards for their amazing collegiality.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Author Contributions

YD: Conceptualization, writing, funding acquisition; RD: Software, writing—review & editing; JW: Conceptualization, writing, visualization, funding acquisition.

Yasmin Demerdash and Jeanne Wilbrandt contributed equally to this work.