Introduction

The prevailing strategy in socio-environmental sustainability governance, formulating goals and assessing their attainment, relies on societal capacity to measure change using relevant and reliable data (Young 2017; Dang and Serajuddin 2020). Along with pledging more ambitious targets, the ability to indicate the pathways and milestones of sustainability by producing more data has expanded rapidly. However, new methodologies, new forms of data-related practises, and ever larger datasets alone will not lead to attaining sustainability goals (Hepp et al. 2022). Reaching them is dependent on action, the application and use of the knowledge produced—in other words, the data must make sense to potential users, foster shared understanding, and guide decision-making (Lyytimäki et al. 2025).

Critical data studies scholars have posited that the collective process of sensemaking around the meanings, capabilities, and audiences of data is embedded in data practises in addition to the methods, instruments, and other technologies (Neff et al. 2017; Bates et al. 2016). This field of research examines the societal and social dimensions of data and can be understood as a reaction to digitalisation and datafication, the growing presence of digital data and data infrastructures, which increasingly shape meaning-making and decision-making across diverse social domains (Hepp et al. 2022).

Herein, we apply the critical data studies approach to digital citizen science (CS), and explore collective sensemaking embedded in its data practises. As a form of knowledge co-production, CS is believed to enhance communal agency, learning, the participation of hard-to-reach and vulnerable groups and assist in achieving more democratic decision-making, thus having transformative potential (e.g., Bela et al. 2016; Turrini et al., 2018; Sauermann et al. 2020; Benyei et al. 2023; von Gönner et al. 2024). CS is envisioned to contribute to decision-making from planning to implementation, monitoring, and evaluation (Turbé et al. 2020; Fraisl et al. 2020). However, most CS projects still operate within an expert-driven crowdsourcing model in which participants primarily function instrumentally, as “sensors” (Land-Zandstra et al. 2021; Frigerio et al. 2021), constraining transformative potential (Pasgaard et al. 2023; Staffa et al. 2022; Mahr and Dickel 2019). Related challenges, such as difficulties in ensuring long-term participant engagement and underutilisation of data among potential users, further hinder the impact of CS (Fraisl et al. 2023).

While social processes have been examined in more collaborative forms of knowledge co-production, such scrutiny is often lacking in crowdsourced modes of CS (Hecker et al. 2018; Haklay 2013; Peltola and Arpin 2018). Existing studies have predominantly explored the social dimensions of CS through lenses of participant motivation and experience, ethics, and methods of communication between citizens and experts (e.g., Christine and Thinyane, 2021; Land-Zandstra et al., 2021; Hecker and Taddicken, 2022; Tauginienė et al. 2025). The nuanced processes of sensemaking are prone to being overlooked, especially when interactions are indirect and mediated through digital platforms (Johnson et al. 2021). Furthermore, while data quality remains a central consideration in CS, limited attention has been paid to how the variety of actors connected to CS initiatives perceive this quality (Balázs et al. 2021).

Environmental monitoring is increasingly reliant on data produced by CS (Poisson et al. 2020). This study focuses on CS in water monitoring, examining the Finnish digital platform Lake-Sea Wiki (Järvi-meriwiki). The Wiki platform summarises basic information about the status of and changes in Finnish lakes (> 1.0 ha) and coastal sea areas, based on authorities’ monitoring data and local citizen observations. We apply insights from critical data studies to analyse the collective sensemaking embedded in the Lake-Sea Wiki–related data practises (Hepp et al. 2022; Neff et al. 2017). Furthermore, we analyse the ability of this information system to act as a boundary object between actors connected to the knowledge produced from different perspectives, facilitating joint understanding (Star and Griesemer 1989).

The research questions are:

How do the actors involved in CS perceive the meanings and usability of the data it produces?

What kind of embedded sensemaking shapes the data practises of digitally formatted CS?

To what extent does this information system function as a boundary object, supporting the development of joint understanding?

By answering these questions, the study not only contributes to the understanding of social dynamics of co-produced data but also explores how CS can support the production of actionable knowledge.

Lake-Sea Wiki

Insufficient data on water bodies has been identified as a major obstacle to the achievement of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs) concerning water quality on a global level (United Nations 2022). In Finland, water monitoring has a long-established tradition in which citizen-collected observations, such as water levels, ice thickness, and snow depth, have played an integral role (Kuusisto 2008). The digital CS platform examined herein, the Finnish Lake-Sea Wiki, was launched in 2011 in response to volunteer citizens using various methods to submit observations to a research institute responsible for water monitoring in Finland. It offers basic information on every Finnish lake (> 1.0 ha), as well as coastal sea areas, integrating citizen observations and official data from authorities. The primary function of Wiki-based platforms is to serve as interactive knowledge infrastructures that are open to contributions from a wide community of users. Their design enables continuous updating and revision, making them self-correcting systems where collective input and peer moderation help ensure accuracy, relevance, and inclusivity over time. Accordingly, Lake-Sea Wiki allows anyone to maintain their own observation site and submit observation data. Key characteristics of the Wiki include user-driven data input and publishing, with no presumption of expert verification. Users can contribute observations, for example of blue-green algae or surface water temperature, upload photographs, engage in discussions, and use the data that others have provided. Lake-Sea Wiki has four different user groups: basic user, experienced user, expert user, and official. Expert users have received training in observations or are otherwise acknowledged as experts in water observation, whereas officials are able to add institutional monitoring data to the Wiki. In 2024, there were a total of 464,000 active users and 740,000 opened sessions in the platform.

Most CS initiatives are either developed in response to institutional needs of researchers or public authorities, or alternatively, emerge from grassroot citizen efforts typically focused on highly localised environmental concerns. Lake-Sea Wiki combines aspects of both: initiated by citizens, yet maintained by a national research institute, the Finnish Environment Institute (Syke). Syke has a central role in the monitoring of waters in Finland. It is responsible for coordinating and implementing national monitoring that generates data on the status and temporal changes of water bodies to inform policy and management. It also develops new methods to improve water quality, and promotes the sustainable use of water resources. By combining data from authorities, citizens trained by authorities, and lay-people, and transitioning to a joint digital Wiki format, Syke aimed to make this data more accessible and encourage broader community participation in environmental monitoring, raising awareness and promoting protection (Kettunen et al. 2016). The Wiki platform is cost-efficient to maintain (Kettunen et al. 2016) and benefits from a self-correcting dynamic as data accumulates through broader participation. Compared with individual CS projects, platforms tend to standardise and automate many processes that were once bespoke to projects (Baudry et al. 2021). Previously, the platform has been studied with a focus on voluntary observer motivation (Palacin et al. 2020).

Theoretical Rooting

Citizen science as a form of knowledge co-production from a critical data studies perspective

The concept of knowledge co-production provides a foundational lens for understanding the intertwined production of knowledge and social order; in other words, ways of knowing the world and seeking to categorise, organise, and change it (Jasanoff 2010; Stone 2016; Norström et al. 2020). In this view, digital environmental CS initiatives are not simply technical platforms for data collection but spaces where civic identities are shaped, sustainability governance is contested, and diverse groups participate, drawing on their respective positions and perspectives (Strasser et al. 2019). The practises of data production and use become embedded within broader social processes, influencing how actors perceive meanings and the actionability of knowledge (Tengö et al. 2021; Skarlatidou et al. 2024).

At the same time, CS is typically characterised as a contributory model of inclusiveness where the focus is on crowdsourcing additional data and citizens are involved solely in data collection, not present or unacknowledged in other phases of the data cycle (e.g., Franzoni et al. 2022; Land-Zandstra et al. 2021; Haklay 2013; Mahr and Dickel 2019; Peltola and Ratamäki 2024). This structure is maintained, or even reinforced, by the prevailing motivation among researchers to use CS to cost-effectively expand the spatial and temporal scope of expert observations (Frigerio et al. 2021). According to the knowledge co-production literature, effective co-production is characterised by contextual grounding, recognition of diverse ways of knowing and doing, clearly defined and shared goals, and opportunities for continuous learning, active engagement, and regular interaction among participants (Norström et al. 2020).

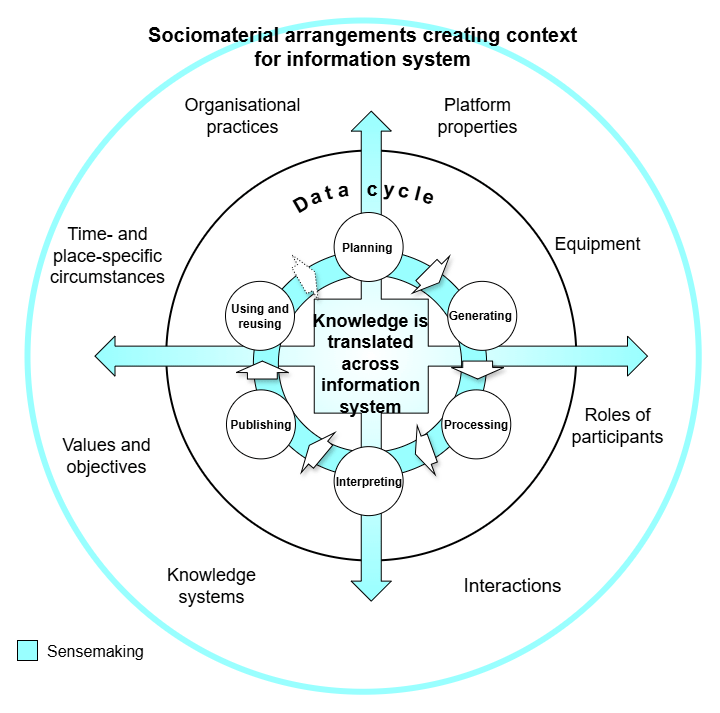

Critical data studies examines ostensibly neutral, depoliticised forms of data-intensive science (Iliadis and Russo 2016), tracing how data are produced, managed, and used (Bates et al. 2016; Stone 2016). It probes more deeply into the stages through which data pass over their “life course,” often visualised as a data cycle (Figure 1), with attention to the consequences of data and the related justice perspectives (Pritchard et al. 2022). The four key components of critiques are 1) data are inherently interpretive, 2) data rely on social and contextual factors for meaning, 3) data are shaped by socio-material arrangements, and 4) data function as a medium for negotiation, communication, and action (Neff et al. 2017).

Figure 1

A data cycle provides a concise visual representation of the stages of data production and use.

Within its framework, as a form of knowledge co-production, CS stands among approaches that tend to overlook the processes of sensemaking in relation to the epistemological frameworks, assumptions, rationales, and socio-material complexities related to data (Hepp et al. 2022). Furthermore, compared with many other types of data-intensive science, CS adds additional layers to the process of sensemaking. The sensemaking in CS is not carried out solely by knowledge producers and seemingly detached knowledge users, but the positions of different actors are multiple and diverse (Eitzel et al. 2017; Bieszczad et al. 2023). From a critical data studies perspective, CS encompasses collective dimensions that go beyond the widely used typologies of citizen participation (e.g. Shirk et al. 2012).

The process of sensemaking in citizen science

Sensemaking is a collective, iterative process through which actors interpret and ascribe meaning to data, their production, and use (Neff et al. 2017; Stone 2016). It incorporates all actors connected to the data in different ways, both producers and users. In CS, sensemaking is not simply individual interpretation, but emerges through interactions with other individuals, observed environments, and organisational structures or platforms. This creates a need to reconcile participants’ differing standards of evidence, credibility, and value.

Embedded in the data practises, deliberate decisions, choices, negotiation, and storytelling take place throughout the phases of a data lifecycle and around socio-material arrangements: first, how data come to be; second, what kinds of meanings the data and their production have and how they get their meaning; and third, what are the proper uses of data and how are they legitimised (Stone 2016; Bates et al. 2016). For example, the objectives set for water monitoring, and the selection of equipment, platforms, observation sites, participant roles, and other socio-material arrangements have developed over a long period of time, shaping contexts of current data practises (Kuusisto 2008). These contexts are reflected in monitoring experts’ views on how monitoring could and should be conducted. The interplay between contexts and views exhibits path dependencies, partly because continuity in monitoring practises over time is itself valued. At the same time, CS has a long-standing tradition in water monitoring, and knowledge of related data practises has accumulated over time (Vuori and Korjonen-Kuusipuro 2018). Information systems formulated within CS have the potential to act as boundary objects, fostering interactive elements in collective sensemaking, translating knowledge, and supporting creation of mutual understanding (Star and Griesemer 1989).

The role of digital citizen science platforms in social processes

Through a cross-cutting process of digitalisation, environmental observations first evolved from visually perceived and notebook-recorded data points to those measured with technical instruments and stored in digital form. Now the evolution continues as digital CS increasingly adopts new functionalities and tools for recording, compiling, analysing, and communicating observations (Cieslik et al. 2018; Franzoni et al. 2022). Many CS projects are at the forefront of using new digital infrastructures and methods of environmental monitoring to facilitate data generation among the public (Franzoni et al. 2022). As the presence of digital technologies in CS is growing, they are poised to play a central part in shaping data practises (Heaton 2024; Charvolin 2024). Digital platforms shape the roles, positions, and relationships among research participants by delineating what they can and are supposed to do, what kinds of interactions are possible, what is considered relevant and valid data, what kinds of meanings the data carries, and the permissible uses of that data (Peltola and Ratamäki 2024). This represents a significant reconfiguration, creating tensions in the process, for example, around whether more established ways of observing the environment may be undermined by reliance on digital crowdsourcing (Giardullo 2023; Kennedy et al. 2022; Johnson et al. 2021).

CS platforms, seeking to stabilise participation, setting norms, and guiding behaviour, play an initial role in the process of crowds becoming a community (Baudry et al. 2021). Digitally mediated information systems, when functioning as boundary objects, can link distant communities, foster collaboration, and integrate local and scientific knowledge (Kanwal et al. 2019; Caccamo et al. 2023; Lauser 2024). Socio-material arrangements shape the specific contexts in which these information systems operate, as structured by the data cycle. In this case study, the arrangements encompass the properties of the Wiki platform, the available physical and digital equipment, the roles of the actors involved in CS and their interactions, the prevailing knowledge systems, the values and objectives of the participants, the organisational practises of their communities, and the time- and place-specific circumstances. The process of sense-making takes place throughout (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Theoretical conceptualisation illustrating the process of sensemaking. An information system is an object formulated in the data cycle, consisting of social, material, and methodological conditions. It acts as a boundary object when supporting mutual understanding between actors, across contextual boundaries.

Material and Methods

We apply the insights of critical data studies in a qualitative content analysis utilising thematic coding and reflexive inquiry (Alvesson and Sköldberg 2018). This approach enables scrutinising CS not merely as a tool for large-scale data collection, but as a socially embedded practice in which data are co-constructed, negotiated, and shaped through collective sensemaking (Neff et al. 2017; Hepp et al. 2022). The study was conducted in the context of a project that investigates and seeks to enhance the utilisation of CS. The project team and the authors of this article include two environmental social scientists, a freshwater management and survey expert, an environmental monitoring expert, and the developer of the Lake-Sea Wiki platform. The authors are affiliated with three different units of Syke, which is responsible for maintaining the platform. This positioning enables access to a profound understanding of the premises of the information system, the socio-material arrangements of its formulation, and the embedded data practises. However, to navigate the methodological complexities created by this positioning, it is essential to maintain critical distance while leveraging contextual closeness, managing the dual roles, and balancing organisational dynamics with research integrity (Coghlan and Brannick 2014). In practice, this was implemented through the triangulation of material sources, utilisation of a multidisciplinary perspective, and the practice of self-reflection.

The material in this study comprises two surveys targeting water monitoring officials and experts at Syke, and active citizen observers and users of Lake-Sea Wiki, material from a joint workshop involving representatives of these two groups, collaborative observations collected during the process, and media material. Separate surveys were conducted for each target group before the workshop, and the results were used to plan the workshop content. Furthermore, we use collaborative observations of the multidisciplinary research team and workshop participants collected during the research process. The material sources are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1

Material sources, methods employed, and contributions to research questions.

| MATERIAL | DESCRIPTION | TYPE OF DATA | METHODS EMPLOYED | CONTRIBUTION TO RESEARCH QUESTIONS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey material | Materials from two surveys targeting active citizen observers (N = 85) and monitoring experts (N = 12) | Two syntheses of survey responses | Content analysis, reflexive inquiry | RQ1, RQ2, RQ3 |

| Workshop material | Materials from a joint workshop with 5 citizen observers, 8 water monitoring experts, 4 researchers and the developer of Lake-Sea Wiki | Two discussion minutes, materials from a joint debriefing session, and materials produced by the workshop participants in Mentimeter | Content analysis, reflexive inquiry | RQ1, RQ2, RQ3 |

| Collaborative observations | Reflections and observations collected by the researchers during the process | Four meeting minutes, reflections of the workshop participants on the conclusions | Content analysis, reflexive inquiry | RQ2, RQ3 |

| Media articles | Media discussion on Lake-Sea Wiki | 211 media articles | Content analysis | RQ1, RQ3 |

The survey for active citizen observers focused on their observation practises, motivational factors, and perceptions on the development of water-related CS (Supplemental File 1: Active Wiki Contributors’ Survey). The survey was sent by email to 187 registered users of Lake-Sea Wiki who had provided observations to the platform in the previous month. The survey was open June–August 2023. Responses were received from 85 observers (46% response rate). Most (68%) recorded observations 10–20 times a year, 16% even more often, while only about 10% contributed year-round, with most reporting mainly in summer. Nearly all (91%) intended to continue at the same pace over the next three years. Respondents were predominantly men (72%) and were older, with the largest age group being 70–79 and none under 30. Most lived in rural or suburban areas (72%), were retired or not working (61%), and were relatively well-educated, with university or vocational college backgrounds (76%).

The survey for water monitoring officials and experts focused on experiences, practises, and perceptions of collaboration with citizens (Supplemental File 2: Monitoring Experts’ Survey). It also explored experts’ views on citizens’ development proposals and on advancing the use of CS more broadly. The surveys served as background material for organising the workshop. The survey was sent to 17 water monitoring experts with various backgrounds, working as experts responsible for parameters of water monitoring or otherwise in water monitoring–related tasks in Syke, and 12 responses were received (response rate 71%). The expert respondents were mostly men (75%) with substantial experience engaging with citizen observations, averaging 11 years. Only two had active connections with at least 26 observers annually. Some were involved in developing services and platforms for data collection.

A joint workshop was organised in November 2023 for citizen observers and water monitoring experts who expressed interest in workshop participation in the survey responses. The participants included 5 citizen observers, 8 water monitoring experts, 4 researchers and authors of this study, and the developer of Lake-Sea Wiki, also an author. It provided the two groups an opportunity to exchange perceptions and reflect on the others’ perspectives. The focuses of the discussions were the benefits and challenges of citizen observation, along with ways to better integrate CS into environmental administration monitoring (Supplemental File 3: Workshop Agenda). Workshop participants were given the opportunity to comment and reflect on the conclusions drawn from the discussions.

The aim of the analysis was to use the survey respondents’ and workshop participants’ descriptions, experiences and reflections in order to identify perceptions of the meanings related to their activities, objectives, and the data they produced. The material was coded into three thematic categories: 1) Sensemaking around meanings, for example, what kinds of meanings were attributed to CS and the data; 2) Sensemaking around usability, for example, what kinds of factors were perceived to affect the usability of the data; and 3) Structuring CS and the platform as a boundary object, for example, current models of interaction and the development proposals for data production and use.

The media analysis was conducted to complement the understanding of perceptions of data usability, particularly from two perspectives: public authorities who commented in the media, and broader public discourse. Articles were retrieved through online searches of Finland’s two major news outlets, Yle and Helsingin Sanomat, on 7 April 2025, using the search terms järviwiki and meriwiki (lake wiki and sea wiki in Finnish). A total of 284 search results were obtained, from which articles concerning the data collected through the platform and/or the practises of its production were analysed (N = 211) (Supplemental File 4: Media Material).

Results and Discussion

The information system of Lake-Sea Wiki as a boundary object

Compared with many of the research approaches that have been examined in critical data studies, CS involves a broad group of data producers participating in the process of sensemaking (Hepp et al. 2022). In the context of Lake-Sea Wiki, approximately 200 voluntary users have actively contributed observations during summer months, with nearly 50 continuing during winter. Furthermore, in wiki-formed CS, the roles of actors connected to the data do not divide unambiguously into producers and users of data. Here, the potential users include, in addition to volunteering citizens and water monitoring authorities providing data, other authorities, the scientific community, local communities, media, and the broader public. When examining the ability of a CS related information system to act as a boundary object, it is therefore essential to recognise this broad range of actors, their potentially shifting roles, and the differing perspectives that exist even within actor groups. For example, monitoring experts are not a homogenous group; divergent ideas about data, their production, and use emerge even among professionals (Neff et al. 2017).

In comparison to many critical data studies applications (Hepp et al. 2022), CS incorporates at least some structured elements of co-production (Norström et al. 2020), for example, by providing a platform for stabilising participation, setting norms, guiding behaviour, and exchanging different types of knowledge (Baudry et al. 2021). Here, the digital platform Lake-Sea Wiki facilitates interaction among actors in an immediate and automated manner but also, to a large extent, indirectly and unintentionally. Information flows through the platform are primarily designed to go one way, without responses or dialogic elements, even though CS inherently introduces two-way dynamics of sensemaking, for example, through the social sphere created by recorded and viewed data points, particularly when actors have multiple overlapping roles in relation to data. The recorded data points communicate what has been meaningful to observers and what they consider relevant for potential knowledge users. In turn, users, from their own perspectives and through diverse modes of use, attribute meanings to the data that were sometimes not foreseen by the producers and that may shape the producers’ future decisions.

However, the sensemaking process is collective primarily in the sense that a wide range of actors participate in it with their own perspectives. These perspectives are not necessarily shared, and their capacity to generate added value for one another is limited. Consequently, as discussed in more detail below, the actors’ interpretations of the meanings and appropriate uses of the data vary considerably. Rather than developing joint understanding, the actors gather and interpret a shared mass of data points through their own perspectives. Nonetheless, on specific occasions, as identified in the workshop by some monitoring experts and active Wiki contributors, there’s a potential to develop shared understanding. For instance, the platform enables rapid communication of acute local environmental changes, potentially allowing quick responses to emerging issues. Sometimes, a monitoring expert stated, it can also help authorities respond to emerging public concern over misunderstood but non-harmful natural phenomena, thus preventing the spread of misinformation and public anxiety.

Tensions of sensemaking: values, data quality, and actionability

CS in the context of Lake-Sea Wiki is a locally grounded activity, closely tied to environmental factors that hold local significance, and with observations primarily recorded near personally meaningful locations, such as vacation areas (58%) or homes (35%). The active Wiki contributors often valued participation for its anticipated benefits for water research, decision-making, and local water users. Some also appreciated it simply as a social hobby, and as a way of recording one’s own observations about the environment. “The good status of waters is the overall goal of the data gathering,” a Wiki contributor participating in the workshop stated, hoping that the data they produce would find use in decision-making that affects the environment. Some Wiki contributors raised concerns that actors with more political power sometimes communicate about the state of local environments in an incomplete manner and called for conveying environmental changes “reliably and without political bias.” They seek to strengthen their arguments, pursue justice through the data (Pritchard et al. 2022), and hope that the environmental changes they find meaningful will also be recognised and validated by others.

Similar to the active Wiki contributors, the monitoring experts also placed significant value on CS and its ability to contribute research, but primarily in an instrumental manner. While citizens may perceive their role in the data cycle as highly significant and wide-ranging, experts tend to assign volunteers a rather clearly defined position (see also Bieszczad et al. 2023). Expert survey answers and workshop comments often stated that the goal of CS is to enable more frequent and comprehensive data collection to complement and calibrate official monitoring efforts cost-effectively. Several monitoring experts underlined that citizen observations bring additional value particularly in areas where environmental authorities or other official bodies do not conduct regular monitoring.

However, while most of the monitoring experts explicitly stated that official monitoring cannot be replaced by citizen-generated data, they generally assessed citizen observations as commensurable with official data. In contrast to the environmental-political concerns of the citizen observers, the experts expressed concerns over the ability of CS to meet scientific quality criteria for it to be used in a complementary manner, like expert data. This perspective implies that a single citizen-generated data point should correspond to a single expert-collected data point to legitimise use. The value of citizen observations was often framed as conditional: “after all, the quality of the data is crucial – if it doesn’t meet the criteria for further use, citizen observations benefit society only in terms of engaging citizens.” When citizen observations were perceived to differ in nature and to have a higher potential for error, it was primarily framed as a quality concern that limits or often even prevents their use. An expert’s survey response stated, “it remains unclear not only what extent the quality of CS data is sufficient, but also what its appropriate uses are.”

Trust not only enables knowledge to become actionable but also defines whose knowledge counts (Kasperowski and Hagen 2022). For example, trust connects local, particular observations to aggregated data and more universal frameworks such as environmental law. The impact of CS remains limited if its contributions to the production of epistemic resources are not acknowledged (Ottinger 2022). The monitoring experts were concerned that sceptical or dismissive attitudes of authorities and decision-makers towards CS may lead to the underutilisation of citizen observations. Wiki-based CS challenges established protocols and validation procedures in which human actors interact with abstract systems to test, establish, or lose trust; however, in some of its forms, Wiki-based CS does not provide sufficient basis for trust grounded in interpersonal interaction (Kasperowski and Hagen 2022).

The approaches to standardisation and scientific quality assurance in CS, as well as its integration into sustainability assessment frameworks, remain subject to ongoing scientific debate (e.g., Fraisl et al. 2020; Balázs et al. 2021). In the workshop, the key factors enabling or restricting data utilisation were closely linked to data quality, including sufficient data volume, continuity, and consistency in observation methods and practises. However, in the analysed media discussion, the quality and comparability of official monitoring data and citizen-generated observations were not considered an issue, as the comment of a regional authority (Yle 17 June 2011) exemplifies: “Within the official monitoring system, we have a network of only 17 observation sites for algal monitoring, which covers only a small fraction of the lakes in this region. All information provided by citizens enhances our overall understanding of the state of the lakes”. This gives emphasis to the notion that the development of standards calls for insights emerging from across diverse transdisciplinary research settings that include also the potential data users (Norström et al. 2020).

Establishing unambiguous standards is not necessarily straightforward: An expert in the workshop noted that, based on comparisons, visual algae observations have been “surprisingly” consistent between experts and citizen scientists, given that there were variations in assessments among experts. Furthermore, the joint workshop revealed that citizen observers, especially those with extensive experience, have developed a strong understanding of the practical factors that influence data quality. Both the monitoring experts and active Wiki contributors had a shared interest in improving the quality of CS data and ensuring their usability. The accumulated practice-based knowledge of the Wiki contributors is currently not systematically utilised in the planning and development of observation activities and data use.

Perceived suitability of citizen science topics

The topics the active Wiki contributors reported monitoring were typically linked to specific environmental concerns, especially the visible or politically contested issues related to recreational use of waters. These topics were associated with land-use change and resulting emissions, other types of pollution, changes in water flow, impacts of climate change, changes in species occurrence, and the effects of restoration. The most observed topics were blue-green algae, surface water temperature, water transparency, and litter levels. New observations proposed by contributors included animal and vegetation species relevant for recreation or policy, and new indicators of pollution entering water bodies.

The monitoring experts, in turn, evaluated topic suitability based on measurability, simplicity, and low equipment needs. Topics requiring complex measuring equipment or extensive expertise were considered especially challenging for citizen observations. Another reason for suitability being challenged was fluctuating public interest. For example, in species monitoring, they seem to attract attention when they first appear, but tracking longer-term population development is difficult as public interest tends to decline once a species becomes abundant. From the experts’ perspective, the most suitable topics were waterbody freezing and ice-out dates as well as shoreline littering, followed by surface water temperature and unusual weather conditions.

This divergence reflects differing priorities: experts focused on data quality and methodological rigour, while citizen observers emphasised perceived relevance. Despite divided views on topic suitability, citizen contributions are already a substantial part of Finnish environmental monitoring for some topics. For example, nearly half of all blue-green algae observations are currently provided by citizens, and over 90% of citizen survey respondents had contributed algae data. Blue-green algae has also been found to be a societally relevant topic as over 80% of the analysed media articles utilised blue-green algae data. However, blue-green algae suitability did not receive unanimous support from experts: 20% of expert respondents considered it unsuitable topic for CS. Some experts found it problematic that citizens tend to record fewer “no algae” observations than experts and were concerned with drawing spatially broad conclusions from limited algae data. Nonetheless, the media often deemed it relevant to report whether citizen observations of the algae situation had been made, and if so, in what quantity, interpreting those observations as an indication of algae growth trends. Media also often used observations from just a few lakes as indicative data when publishing news reporting the regional algae situation.

Restructuring citizen science data practises for enhanced usability

The workshop discussion and the survey responses elicited development ideas focused on increasing the number of observations, fostering observer commitment, improving data quality, and ultimately, enhancing data usability. The need to expand the volume of observations was linked to debates on data quality in two ways. First, a sufficient volume of data was considered essential to ensure data reliability. Group-based participation, encouraged by hobby communities or associations, was seen as especially effective at increasing data volume and geographic coverage. To address the lack of accessible equipment, it was proposed that measurement tools could be distributed through schools, hobby groups, and public libraries. Second, expert-led quality assurance was seen as increasingly challenging as the number of observers and observations grows. The core purpose of the Wiki-formed platforms is to function as community-driven, self-correcting systems. However, the experts didn’t quite trust this model and instead called for external quality control mechanisms. Automation, through machine learning, image analysis, and visualization tools, was identified as a way to reduce manual effort. The development proposals related to increasing data volume as a means to address quality issues appear to challenge the assumption that CS data must meet the same standards as expert-produced data.

A large part of the discussion related to development proposals was connected to different forms of interaction. From the experts’ perspective, improved communication regarding data needs, targeted observation campaigns, and more regular feedback were seen as essential for sustaining citizen engagement in data gathering. Many emphasised organising observer training in partnership with non-governmental organisations, and shifting the training responsibilities gradually to these organisations. In general, the monitoring experts viewed measures that promote community engagement more positively the less resources these measures required from them: “If experts should make a significant effort and use a lot of resources for CS data, it would undermine the idea that citizen observations are an easy and inexpensive way to obtain observations”. Experts expressed concerns about managing large volumes of two-way communication, which is currently not a structured part of CS workflows. While crowdsourced big data was considered manageable, crowdsourced communication could “overwhelm,” as an expert described.

While the experts remained cautious about involving citizens in the planning and interpretation phases of the data cycle, active Wiki contributors emphasised the importance of early involvement in designing data practises, including co-developing parameter definition and input forms. One of the key messages of the Wiki contributors was that issues and development needs related to the quality of CS data should be addressed through collaboration with experienced citizen observers. The Wiki contributors called for strengthening the knowledge exchange between all actors involved in CS, including data users. They requested more active engagement that goes beyond the digital interface, feedback from experts on how data have been utilised, and co-development to improve data practises to enhance data usability.

Conclusions

This study examines sensemaking, embedded in data practises of CS, as a collective process shaped by actors who are involved in different ways. By exploring these actor’s perceptions, this study highlighted the diverse meanings attributed to CS and the data it produces. While digital information systems of CS can facilitate broad participation and systematic data collection, they do not, in themselves, guarantee creation of shared understanding. Established data practises of CS have been formulated primarily with the idea that data should flow to experts unidirectionally, and not all experts see the value in changing this model. Whereas monitoring experts tend to categorise CS within a clearly defined and limited role, emphasising institutional objectives of data production, active citizen observers may regard their role as more influential, thereby, perhaps unintentionally, challenging historically established data practises. The divergence in emphasis, between increased data production and democratic engagement, reflects epistemic tensions within the CS field, and suggests a need for more reflexive, dialogic approaches. This study demonstrates that active citizen observers are not only concerned with contributing data, but also with data reliability, relevance, and application in addressing the environmental problems the participants encounter. Overlooking the experiences of citizen observers can undermine their engagement and lead to the ineffective implementation of CS, making knowledge production processes less transparent and less sensitive to context-specific meanings and concerns.

This study suggests how CS could move beyond a linear, extractive model of data collection toward a more collaborative and adaptive framework that acknowledges and values experiential knowledge, develops more consistent data practises, and enables the co-creation of shared meanings. Such an approach requires rethinking the roles, responsibilities, and communication strategies across all actors, as well as investing in institutional arrangements that foster long-term interaction and knowledge translation. Environmental CS is not merely an activity related to the environment, but also carries broader societal significance, for example, as a means of seeking recognition and fostering a sense of belonging. Better recognition of these dimensions may also help sustain the desired flow of observations over time.

Supplementary files

The Supplementary files for this article can be found as follows:

Ethics and Consent

The research follows the ethical guidelines of the Finnish National Board on Research Integrity TENK. According to the guidelines, no ethical review was required.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all actors taking part in this process and sharing their experiences and insights with us. We also acknowledge Uula Saastamoinen and Maria Ojala for their helpful comments.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Author Contributions

Suvi Vikström: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – Original Draft, Writing - Review and Editing, Visualization

Elise Järvenpää: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – Original Draft

Virpi Lehtoranta: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – Original Draft, Writing - Review and Editing

Matti Lindholm: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – Original Draft

Taru Peltola: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review and Editing, Project administration