Introduction

Involving members of the public in the scientific process is increasingly being recognised as a cost- and time-effective means to obtain vast quantities of valuable scientific data over large temporal and spatial scales (Bonney et al. 2014; McKinley et al. 2017; Santos-Fernandez et al. 2023). Global advancement in technologies and the increasing connectivity of scientific communities through the Internet have greatly increased the scope and reach of citizen science projects, enabling citizen scientists to expand their involvement in data collection and data processing, and improving the inclusivity of citizen science projects (Dickinson et al. 2012; Bonney et al. 2014; Sharma et al. 2019). The concept of citizen science is broad-reaching, extending into many scientific fields, including biology, astronomy, environmental science, computer science, geology, climate science, and medical science (Davis, Zhu, and Finkler 2023).

The collaboration between professional and volunteer scientists offers unique methods to efficiently increase the quantities of scientific data, while also encouraging community engagement in scientific research and outcomes (Riesch and Potter 2013). However, despite offering major benefits to both the professional and volunteer scientists, the quality and reliability of citizen science data remains a common concern and source of debate, potentially resulting in an under-utilisation of citizen science within professional scientific communities (e.g., Riesch and Potter 2013; Bonney et al. 2014; Lukyanenko, Parsons, and Wiersma 2016; Davis, Zhu, and Finkler 2023).

Citizen science projects are invaluable for collecting data on temporal and spatial scales that are otherwise impossible using traditional scientific methods (Kobori et al. 2016; McKinley et al. 2017). With millions of citizen scientists contributing valuable biodiversity data globally, citizen science projects are major contributors to biodiversity observational records. Crowdsourcing the identification of organisms (sourcing data and knowledge from large numbers of citizen scientists) provides an effective method for rapidly processing and classifying these large citizen science datasets, while also encouraging citizen learning and engagement in the scientific process beyond data collection (Hsing et al. 2018). Projects that crowdsource data classifications often utilise consensus algorithms to improve data quality, whereby classifications are aggregated from multiple user responses, rather than relying on individual classifications (Swanson et al. 2016; Hsing et al. 2018; Adler, Green, and Sekercioglu 2020). Consensus algorithms require a pre-determined number of volunteers to classify each task, with consensus classification determined by aggregating responses and selecting the most common response (Mugford et al. 2021), or setting a threshold for the number of volunteers required to agree upon a classification (e.g., Swanson et al. 2016; Lawson et al. 2022). Determining the most efficient and accurate level of consensus to be reached in order to retire a task is an important consideration for projects utilising consensus algorithms to maximise the efficiency of the project while ensuring a high level of data quality (Kamar, Hacker, and Horvitz 2012). Such a determination requires researchers to assess the accuracy with which volunteers identify organisms from a variety of crowdsourcing projects.

While previous crowdsourcing projects have reported volunteer identification accuracies of 70–95% (Kosmala et al. 2016), accuracy is highly variable according to taxonomic group (Kosmala et al. 2016), task complexity (Genet and Sargent 2003; Kosmala et al. 2016), species (e.g., Genet and Sargent 2003; Swanson et al. 2015; Lawson et al. 2022), and individual volunteer skill (Kosmala et al. 2016; Siddharthan et al. 2016; Santos-Fernandez et al. 2023). To date, the majority of projects that crowdsource organism identification process image datasets (e.g., DigiVol 2011; Snapshot Serengeti – Swanson et al. 2016; QuestaGame 2023; iNaturalist 2024), and are taxonomically biased towards insects, plants, and birds (Chandler et al. 2017).

Acoustic monitoring is becoming increasingly prevalent as a non-invasive method of monitoring acoustically communicating taxa, particularly those that are rare or otherwise elusive in their environments (Penar, Magiera, and Klocek 2020). For taxa such as frogs, bats, cicadas, and orthopterans, acoustic signals are often reliable, non-invasive forms of species identification, and provide key information on species taxonomy and ecology (Obrist et al. 2010). However, few crowdsourcing platforms focus on crowdsourcing species identification from acoustic media.

Auditory analysis presents unique challenges for species identification that are not found in visual analysis. While some of the most popular image-based crowdsourcing projects require the identification of a single species per task (e.g. Snapshot Serengeti – Swanson et al. 2015; QuestaGame 2023; iNaturalist 2024), audio-based identification tasks often contain an added layer of complexity by featuring multiple species per task (e.g., frogs – Genet and Sargent 2003; Rowley et al. 2019; birds – Farr, Ngo, and Olsen 2023). In addition to increasing cognitive load, multi-species identification can prove challenging through acoustic masking because species with low-amplitude calls, inconspicuous calls, or infrequent calling behaviour are unlikely to be detected or accurately identified within large, multi-species choruses (Genet and Sargent 2003). Further, the auditory scene generally contains complex environmental noise, which increases the effort required to process and identify interfering sources of sound through auditory scene analysis (Bregman 1993; Bregman 1994). In the case of frogs, environmental noise such as insect calls, human noise, or the sounds of wind and water may mask frog vocalisations. As such, audio-based identification tasks may be particularly challenging for citizen scientists; however, few evaluations of audio-based species identification by citizen scientists have been conducted.

While the use of artificial intelligence and machine learning is increasingly being explored for automatic acoustic species identification, they face similar challenges with background noise, variable recording quality, and multi-species choruses (Guerrero et al. 2023). Because crowdsourcing enables more nuanced approaches to species identification (e.g., Westphal et al. 2022) and provides the additional benefit of engaging citizen scientists in scientific research and outcomes (Hsing et al. 2018), it remains important to continue investigating the role of citizen scientists in species identification.

Here, we developed a suite of audio analysis tasks to evaluate the efficiency and accuracy of crowdsourcing species identifications from audio recordings of frogs. We used audio recordings from the national Australian FrogID citizen science project (Rowley et al. 2019), which currently relies on recordings of calling frogs being identified by experts in frog-call identification. By comparing citizen scientist identifications with these expert-validated recordings of frog calls from the FrogID database, we aimed to determine the accuracy with which untrained volunteers identify frog species from audio recordings, and further explore the unique challenges posed by audio identification. In addition, we aimed to determine the impact of applying consensus thresholds on the efficiency and accuracy of crowdsourced identifications, and in doing so, determine the optimal consensus threshold for this study.

Methods

FrogID dataset

FrogID is an ongoing citizen science project that collects frog biodiversity data within Australia from smartphone recordings of male frog advertisement calls (Rowley et al. 2019). Citizen scientists use the FrogID smartphone app to submit 20–60-second audio recordings of male frog advertisement calls. The app automatically adds recording time, latitude, longitude, and an estimate of location accuracy. One or more FrogID validators then identify all of the frog species calling in each recording. All validators receive extensive training in frog-call identification, are able to seek advice and assistance from a network of frog-call experts, and receive ongoing feedback.

The FrogID dataset comprises more than 670,000 validated audio recordings throughout Australia, representing more than one million validated frog records. Up to 13 frog species have been identified in a single recording, with an average of 1.6 frog species per recording (Rowley and Callaghan 2022).

Volunteer recruitment and training

The opportunity to participate in the FrogID Audio Analysis project was shared through the FrogID eNewsletter and the social media channels of FrogID, DigiVol, and the Australian Museum to engage a wide range of citizen scientists. The FrogID eNewsletter was circulated to more than 65,000 citizen scientists. While this targeted citizen scientists already engaged in the FrogID project, participation was not restricted to FrogID users, with more than 10,000 of the existing DigiVol volunteers who transcribe text and identify animals from camera trap images also invited to take part. Participation was entirely voluntary, with no requirements placed on the volunteers to contribute more than one identification. To minimise bias, we did not incentivise participation in the project (Raddick et al. 2013).

Prior to commencing the FrogID Audio Analysis project, we presented the volunteers with a tutorial on navigating the program interface and completing the audio identification tasks, including advice on filtering the potential frog species. The tutorial was not compulsory for the volunteer to complete prior to progressing to participation. We also provided the volunteers with a complete list of all 41 frog species, which had been recorded by FrogID users in the Sydney Greater Capital City Statistical Areas (GCCSA). The species list included a call description, call type, conservation status, and occurrence status for each species, and highlighted the ten most commonly encountered species in the Sydney GCCSA. These training resources remained available to volunteers throughout the project. While intensive taxon-specific training improves identification accuracy in a range of projects (e.g., Ratnieks et al. 2016; Salome-Diaz et al. 2023; Farr, Ngo, and Olsen 2023), the training resources we provided to the volunteers of the FrogID Audio Analysis project reflect current practices in real-world online crowdsourcing platforms (e.g., DigiVol 2011; iNaturalist 2024; Zooniverse 2024). We did not provide the volunteers with feedback throughout their involvement in the project.

FrogID Audio Analysis project

The FrogID Audio Analysis project took place from August 2022 to February 2023 and was hosted on the online DigiVol platform (DigiVol 2011), a citizen science platform formed through collaboration between the Australian Museum and the Atlas of Living Australia. Over the course of the project, we released four non-concurrent expeditions, which featured unique subsets of our FrogID dataset. The first expedition comprised 1,000 audio analysis tasks, while the subsequent expeditions each comprised 250 audio analysis tasks. Each audio analysis task corresponded to an expert-validated recording from the FrogID dataset. These recordings were randomly subset from all FrogID records that had been validated and published up to 26 July, 2022 in the Sydney GCCSA.

The FrogID Audio Analysis project required volunteers to listen to a 20–60-second FrogID audio recording and identify each frog species calling in the recording. The FrogID Audio Analysis interface featured a visual oscillogram of an audio recording, and a selection window in which volunteers could select the calling frog species (Figure 1). The selection window included photographs and sample audio recordings of each of the 41 possible frog species. To aid in identification, volunteers were able to filter the species according to call type, commonness, and conservation status. We did not impose a time limit for task completion, enabling the volunteers to replay the audio recordings as needed. The volunteers were also asked to determine whether human or insect noise was present in the recording, or if there were no audible animals.

Figure 1

User interface of the FrogID Audio Analysis project on the DigiVol crowdsourcing platform, including a visual oscillogram of the 20–60 second FrogID sound recording, and sample photographs and audio of potential frog species.

We randomly circulated each audio analysis task to multiple volunteers, and retired each task after either five or six separate identifications had been made. To minimise bias and ensure identifications were determined independently, previous identifications made by other volunteers or expert validators were not available to the volunteer.

The final FrogID Audio Analysis project comprised 1,748 audio recordings which received a minimum of five identifications, thereby meeting the requirements for retirement.

Accuracy of volunteer identifications

To evaluate the accuracy of the FrogID Audio Analysis project, we compared the identifications made by the volunteers with identifications from expert validators at the Australian Museum. We classified responses as either correct or incorrect. Correct responses were those in which the volunteer identified all the calling frog species, or correctly noted when no frog species were calling. Incorrect responses were those in which volunteers were unable to correctly identify all calling frog species. We determined overall accuracy to be the proportion of all tasks that had been correctly identified by the volunteers.

To determine the influence of multi-species choruses on volunteer accuracy, and to examine differences in species detectability, we further divided the incorrect responses into partially correct and completely incorrect responses. Partially correct responses were those in which the volunteer correctly identified at least one calling frog species, but either selected additional species which were not calling, or did not identify each calling frog species. Completely incorrect responses were those in which volunteers were unable to correctly identify any calling frog species. For the purposes of determining the accuracy with which volunteers identify frogs, partially correct responses were ultimately considered to be incorrect, and as such, we did not analyse them further.

To determine whether task complexity influenced volunteer accuracy, we examined whether accuracy varied according to the number of frog species calling in a recording. As identification accuracy varies according to species across many taxa (e.g., Swanson et al. 2016; Sharma et al. 2019; Lawson et al. 2022) including frogs (Genet and Sargent 2003), we also compared the accuracy with which volunteers identified different frog species.

Consensus threshold

We compared the accuracy and efficiency of four different thresholds of agreement: Agreement of Two Volunteers, Agreement of Three Volunteers, Agreement of Four Volunteers, and Agreement of Five Volunteers. For each threshold of agreement, we considered a task to meet the requirements for retirement if the pre-determined number of volunteers agreed on an identification. As volunteers could suggest multiple species per task, the consensus response could also be determined from the number of times each species was suggested. As this method yields similar levels of accuracy (Supplemental File 1: Supplemental Figure 1; Supplemental File 2: Supplemental Figure 2), we chose to only determine the consensus response from exact matches between volunteer responses. To evaluate the efficiency of each threshold of agreement, we aggregated the volunteer responses and determined the percentage of all tasks that would meet the requirements for retirement, and the percentage of all tasks that would be identified correctly. To determine the optimal number of volunteer responses required for retirement, we examined whether the accuracy and efficiency of each consensus threshold varied according to the number of volunteers who provided an identification.

Volunteer engagement and accuracy

We evaluated the individual skill levels of the FrogID Audio Analysis volunteers according to the proportion of tasks correctly identified. We measured volunteer engagement as the total number of identification tasks a volunteer completed. Ongoing engagement over time is predicted to improve the individual accuracy of volunteers (Kosmala et al. 2016; Santos-Fernandez and Mengersen 2021), as has been confirmed in experimental datasets (e.g., Swanson et al. 2016). We evaluated ongoing engagement according to the number of repeat identification sessions in which a volunteer was involved, and the number of expeditions in which a volunteer participated. We conducted Pearson’s Correlation Tests to determine whether accuracy was correlated with engagement across all volunteers and for volunteers who had contributed at least ten identifications to the project. Additionally, we conducted Pearson’s Correlation Tests to determine whether accuracy was correlated with the number of repeat identification sessions.

Results

A total of 8,933 volunteer responses were submitted by 233 individual volunteers to the FrogID Audio Analysis project from August 2022 to February 2023. These responses corresponded to 1,748 unique FrogID audio recordings. The expert validators identified 28 frog species in the audio analysis dataset, while the volunteers identified 40 frog species.

Accuracy of volunteer identifications

Overall, 57% of the 8,933 volunteer responses exactly matched the expert validations, 18% were partially correct, and 24% were incorrect.

The expert validators identified up to seven frog species calling in a single recording. As the number of frog species in each recording increased, the accuracy of volunteer responses decreased (Table 1). Volunteer accuracy was highest in recordings of a single frog species, and recordings with no frog species, while recordings with two or more frog species calling were incorrectly identified in more than 50% of cases.

Table 1

Accuracy of responses according to the number of frog species calling.

| NUMBER OF SPECIES CALLING | CORRECT | PARTIALLY CORRECT | INCORRECT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zero (not a frog) | 69% | N/A | 31% |

| One | 69% | 4% | 27% |

| Two | 35% | 48% | 17% |

| Three | 24% | 63% | 13% |

| Four | 12% | 88% | 0% |

| Five | 4% | 91% | 5% |

| Six | 2% | 92% | 6% |

| Seven | 10% | 60% | 30% |

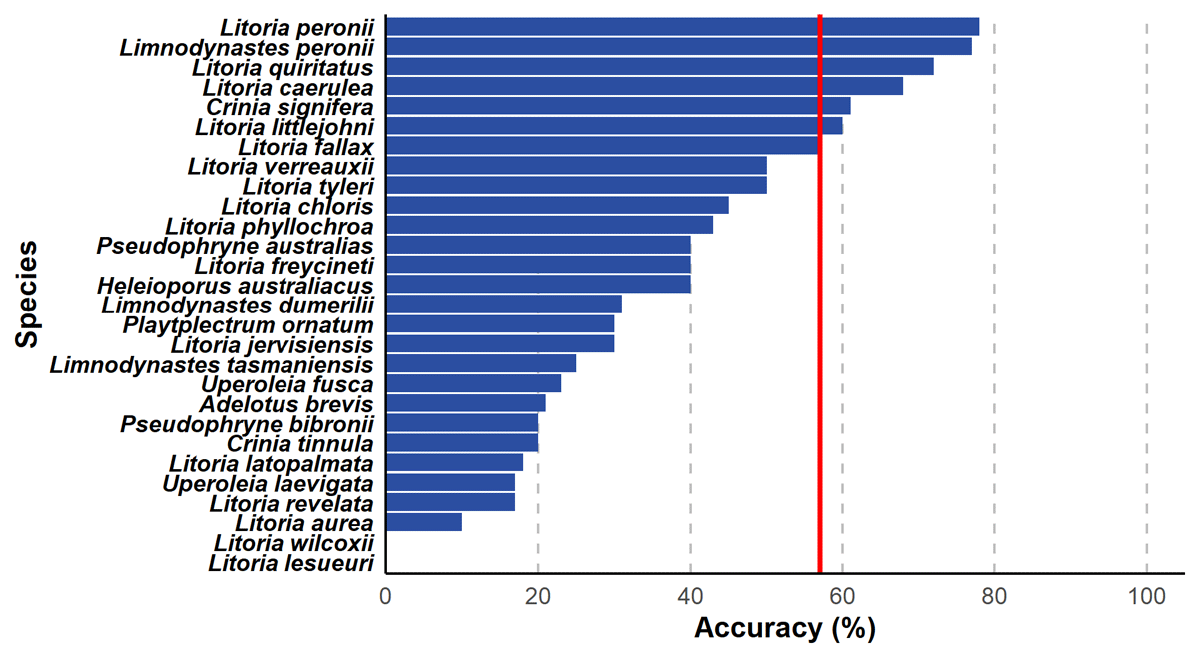

Accuracy also varied according to species identity (Figure 2). The accuracy with which different species were identified ranged from 0% for Litoria lesueuri (n = 5) and Litoria wilcoxii (n = 15), to 78% for Litoria peronii (n = 2247). Of the 28 identified species, 68% were identified less than 50% of the time, with only seven species correctly identified in more than 50% of occurrences. Four of the five species identified with the highest levels of accuracy are among the ten most commonly recorded frogs of the Sydney GCCSA and were present in the greatest number of recordings in the audio analysis dataset.

Figure 2

Histogram of the 28 frog species identified by the expert validators in the FrogID Audio Analysis project, displayed as the percentage of the total number of records of each species which received a correct identification. Red line indicates the overall accuracy of all species combined.

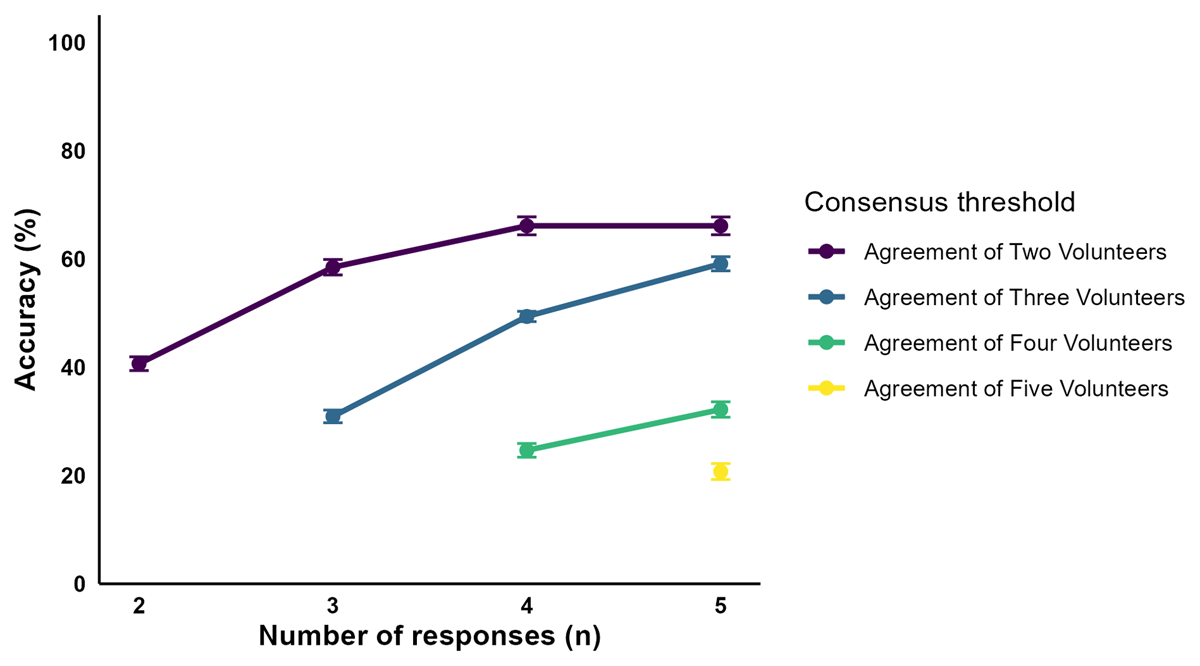

Consensus threshold

For each consensus threshold, aggregating responses from a higher number of volunteer responses increased the probability that a task would be retired (Figure 3). Likewise, the percentage of all tasks that would be retired with a correct identification increased as the number of volunteer responses increased (Figure 4). A maximum of 95% of tasks reached retirement when we applied a threshold of Agreement of Two Volunteers, and retired the task after five responses were received. Likewise, we attained a maximum accuracy of 66% when we required Agreement of Two Volunteers from five responses. While an Agreement of Two Volunteers from four responses also yielded an accuracy of 66%, only 90% of tasks reached a consensus. The minimum accuracy was attained for an Agreement of Five Volunteers, with 22% of tasks reaching the required consensus threshold, and 21% of all tasks being identified correctly.

Figure 3

Mean percentage (with 95% confidence interval) of tasks which reach the threshold for retirement according to each consensus threshold and number of volunteer responses.

Figure 4

Mean percentage (with 95% confidence interval) of tasks that reach the threshold for retirement and are identified correctly according to each consensus threshold and number of volunteer responses.

Volunteer engagement

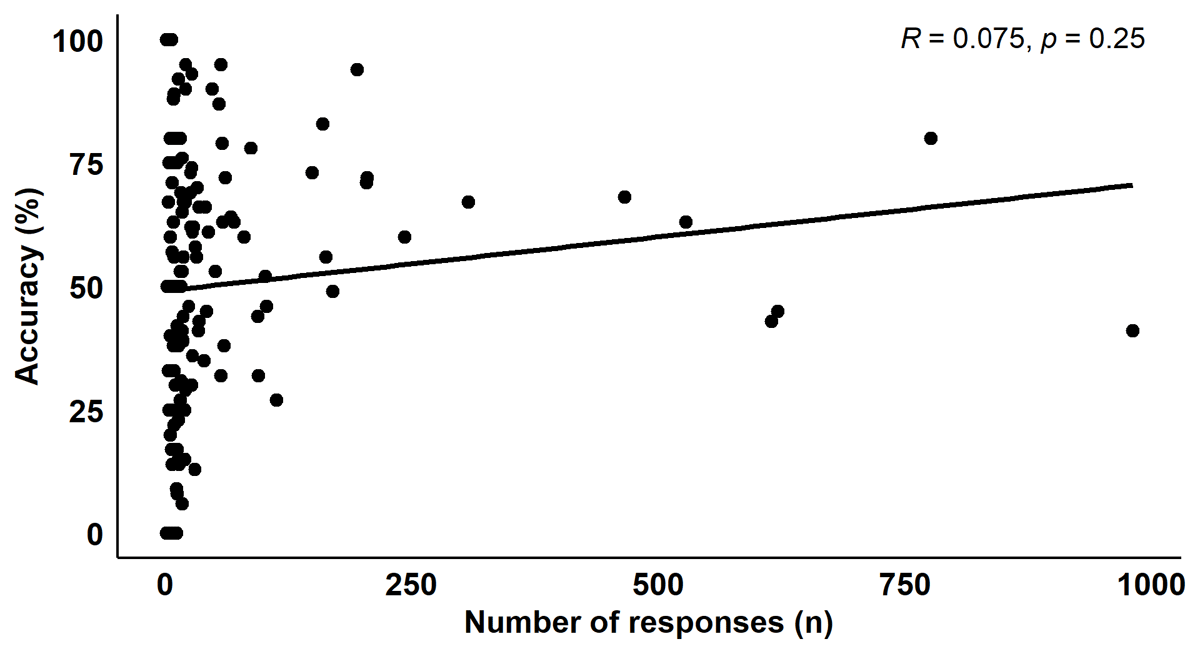

Accuracy and engagement varied considerably between individuals (Figure 5). Overall, 18% (n = 42) of volunteers submitted one identification, and 43% (n = 101) of volunteers submitted ten or more identifications. On average, each volunteer contributed 38 identifications to the project, with individual engagement ranging from one identification to 981 identifications. Over 50% of the entire dataset was contributed to by 3% (n = 8) of all volunteers. Overall, volunteers with fewer than 50 responses had an average accuracy of 48% (range 0% to 100%), volunteers with between 50 and 100 responses had an average accuracy of 61% (range 32% to 95%), and volunteers with more than 100 responses had an average accuracy of 61% (range 27% to 94%). Engagement was not correlated with accuracy across all volunteers (r231 = 0.08, p = 0.25; Figure 6), or for volunteers with ten or more identifications (r99 = 0.13, p = 0.19).

Figure 5

Histogram displaying the number of responses recorded by each individual volunteer, ordered from most to fewest contributions, and indicated by the total percentage of all volunteers. Red line indicates the position of 50% of all responses, which was contributed to by the top 3% of volunteers.

Figure 6

Scatterplot of individual volunteer accuracy according to the number of responses contributed to the audio analysis project, including a regression line derived from a Pearson’s Correlation Test.

Individual volunteer accuracy ranged from 0% to 100%, with an average accuracy of 50%. One quarter of the volunteers accurately identified recordings over 75% of the time. Of the 101 volunteers who identified ten or more tasks, accuracy ranged between 0% and 95%, with an average accuracy of 52%.

The majority of volunteers (66%; n = 155) completed identification tasks on only one day. Ten volunteers completed audio analysis tasks on ten or more separate occasions. Individual accuracy was not correlated with the number of repeat identification sessions across the entire dataset (r231 = 0.06, p = 0.35; Figure 7), or for volunteers with more than ten identifications (r99 = 0.09, p = 0.36). The majority of volunteers participated in one expedition, 12% (n = 27) of the volunteers participated in at least two, and 3% (n = 6) of the volunteers participated in all four audio analysis expeditions. On average, the volunteers who participated in two expeditions decreased in accuracy by 3% (range decrease of 53% and increase of 39% accuracy) between their first and second expeditions. On average, the volunteers who participated in all four expeditions decreased in accuracy by 30% (range decrease of 73% and no change) between the first and fourth expeditions.

Figure 7

Scatterplot of individual volunteer accuracy according to the number of repeat identification sessions (days), including a regression line derived from a Pearson’s Correlation Test.

Discussion

By comparing volunteer identifications with expert-validated data from the FrogID citizen science project, we demonstrate the abilities of untrained citizen scientists to identify frog species from audio recordings. Overall, 57% of all volunteer identifications were correct. However, identification accuracy varied according to task complexity, as determined by the number of frog species calling and species identity, and was highly variable amongst individual volunteers. By aggregating volunteer responses, we attained a maximum accuracy of 66% and a maximum 95% of tasks reaching consensus when we applied a consensus threshold of Agreement of Two Volunteers and a task was responded to by five volunteers.

High accuracy of volunteer identifications has been reported in a variety of image-based citizen science projects (e.g., Swanson et al. 2015; Siddharthan et al. 2016; Hsing et al. 2018). However, our analysis of volunteer identifications of frog audio recordings using similar methodology resulted in a substantially lesser overall identification accuracy. While similar audio-based citizen science projects have reported higher identification accuracies (e.g., Genet and Sargent 2003; Farr, Ngo, and Olsen 2023), these results are likewise considerably lower than most image-based citizen science projects. These results clearly highlight the differences in complexity between auditory and visual media for organism identification.

Multi-species identification tasks present unique challenges to audio identification by creating a complex auditory scene and often featuring overlapping sources of sound. Complex auditory scenes require cognitive processing to separate overlapping sources of sound and identify the individual components of a mixture of sounds through auditory scene analysis (Bregman 1993; Bregman 1994). Within the FrogID Audio Analysis project, up to seven frog species were present in each audio recording, with volunteers required to identify all present species. Our results indicate that citizen scientists are less likely to accurately identify frog species within choruses of multiple species than recordings of a single species. Similarly, our results demonstrate that it is particularly challenging for volunteers to achieve consensus on multi-species identification tasks. The unique challenges posed by multi-species identification that are not present in image-based identification tasks likely contributed to the lower accuracies reported for audio-based rather than image-based crowdsourcing projects.

Identification accuracy varied by species, as has been previously reported in both image-based and audio-based projects focussing on mammals (Swanson et al. 2015; Swanson et al. 2016; Hsing et al. 2018), insects (Siddharthan et al. 2016; Sharma et al. 2019), marine invertebrates (Lawson et al. 2022), and frogs (Genet and Sargent 2003). Commonness was a reliable indicator of accuracy in this study. Of the five species identified with the highest accuracy, four were listed amongst the ten most common frogs of the Sydney GCCSA, indicating that common frog species may be more likely to be accurately identified than uncommon species. This is reflective of previous studies, in which species with the highest levels of detectability are typically the most common species (e.g., Siddharthan et al. 2016; Lawson et al. 2022).

Aggregating responses from multiple volunteers enables crowdsourcing projects to maximise volunteer accuracy. In this study, we identified the optimal consensus threshold to be an Agreement of Two Volunteers from five responses, for which 95% of tasks met the minimum requirements for retirement, and 66% of all tasks were accurately identified. Although this is an increase from non-aggregated identification accuracy, it is still a considerably lower accuracy than other similar studies (e.g., Genet and Sargent 2003; Kosmala et al. 2016). Our results support the findings of previous studies, where accepting a greater number of volunteer responses corresponded to an increase in both the proportion of tasks that reached consensus, and the proportion of tasks that were correctly identified (e.g., Swanson et al. 2016; Hsing et al. 2018; Lawson et al. 2022). Although requiring more volunteer responses for a task to reach retirement would evidently increase the accuracy and reliability of data, the increased volunteer effort to retire each task would likely result in fewer tasks reaching retirement. As such, the trade-off between volunteer accuracy and efficiency must be considered in determining the optimal consensus threshold for practical applications.

While application of a consensus threshold increases the accuracy with which a task is identified, tasks that do not meet the minimum requirements for consensus remain unidentified. According to the optimal consensus threshold for the FrogID Audio Analysis project, 5% of all tasks would not meet the requirements for retirement. Similarly, when BeeWatch data are identified using a consensus model, 27% of tasks fail to achieve a consensus (Siddharthan et al. 2016), whereas requiring an Agreement of Five Volunteers results in 22% of marine invertebrate images failing to achieve consensus (Lawson et al. 2022). By achieving consensus through reputational weighting, 17% of all iSpot tasks are unable to reach a consensus (Silvertown et al. 2015). Tasks that fail to reach a consensus may require circulation to additional volunteers, or review from expert validators. Alternatively, inviting users to review their identifications of tasks that did not reach a consensus resulted in increased accuracy and the proportion of tasks that reached consensus, particularly in cases where social and collaborative learning were encouraged (Sharma et al. 2022).

Weighting responses according to skill level is frequently employed in citizen science projects to improve accuracy and to reduce the number of volunteers required to classify tasks, therefore enhancing data quality and efficiency (Hines et al. 2015; Kosmala et al. 2016; Santos-Fernandez and Mengersen 2021; Santos-Fernandez et al. 2023). In practice, taxon-specific reputational weighting algorithms are applied to the citizen science projects iSpot and QuestaGame, where volunteers gain reputation through providing correct identifications, thereby increasing the weighting of their future contributions (Silvertown et al. 2015; QuestaGame 2023). Applying equal weight to all responses can be particularly problematic for complex tasks, where it is expected that few correct identifications will be made, and those only by more highly skilled volunteers (Santos-Fernandez et al. 2023). Given the variable complexity of FrogID audio recordings, the high variability in species detectability, and the complex nature of multi-species identification, it would be beneficial to explore the impact of weighting volunteer responses on identification accuracy.

Volunteer training is an effective means of improving volunteer accuracy, as the type and extent of training volunteers receive prior to participating in identification tasks influences accuracy (e.g., Ratnieks et al. 2016; Salome-Diaz et al. 2023; Farr, Ngo, and Olsen 2023). The non-compulsory online tutorial presented to the participants in the FrogID Audio Analysis project reflects current training practices for online crowdsourcing platforms (e.g., DigiVol 2011; iNaturalist 2024; Zooniverse 2024). Given that accuracy levels in this study were not consistent with those required for reliability in scientific research, further exploration of methods to improve accuracy is imperative if crowdsourcing is to play a role in future identification in the FrogID project. It would be valuable to develop more rigorous training protocols for frog-call identification, and to examine whether volunteer training influences the accuracy of the volunteers. Such training protocols may draw from existing training methods utilised for the expert FrogID validators.

Volunteer accuracy is often linked to the structure and design of user interfaces. User interface designs that enable user-directed taxon filtering according to identification features report higher accuracies than interface designs requiring users to directly compare features between potential taxa (Sharma et al. 2019). Such designs minimise cognitive load, thus creating simpler and more intuitive platforms, and improving the accuracy with which volunteers respond to tasks (Rahmanian and Davis 2014; Sharma et al. 2019). While the user interface developed for the FrogID Audio Analysis project enabled user-directed taxon filtering, it would be valuable to explore the influence of other potential interface designs on volunteer accuracy and engagement.

Methods to enhance data quality and reliability are at the forefront of citizen science projects, including the necessity to maintain volunteer engagement (Riesch and Potter 2013). We observed low levels of engagement amongst the FrogID Audio Analysis volunteers, comparable with other citizen science projects (e.g., Siddharthan et al. 2016; Hsing et al. 2018; Lawson et al. 2022). While the accuracy of individual volunteers is predicted to increase as a user gains experience with a project over time, we did not observe any correlation between accuracy and either number of identifications, or number of repeat identification sessions. Likewise, number of years of experience was not correlated with volunteer accuracy for participants in anuran call surveys (Genet and Sargent 2003). In contrast, the accuracy of Snapshot Serengeti volunteers increased from 78.5% for new volunteers to over 90% for volunteers with more than 100 identifications (Kosmala et al. 2016).

Providing volunteers with ongoing training and feedback is likewise important for enhancing and maintaining accuracy and engagement. The volunteers of the FrogID Audio Analysis project were not provided with feedback during the project, potentially limiting their ability to learn and improve identification accuracy throughout their involvement in the project. Previous research has indicated that providing volunteers with detailed feedback aimed at developing identification skills greatly improves volunteer skill and accuracy, and increases both volunteer satisfaction and confidence in identification skills, promoting ongoing engagement (van der Wal et al. 2016). Ensuring volunteer satisfaction is essential in maintaining volunteer engagement over time, and is a consideration that should not be overlooked. Feedback mechanisms aimed at improving volunteer accuracy and maintaining volunteer interest and engagement should be implemented in future research to more completely understand the role of feedback in audio-based citizen science projects.

Volunteer engagement is likely influenced by the strategies employed to promote and encourage volunteer participation. It would be valuable to explore the role of targeted engagement strategies on volunteer engagement and accuracy. Incentivisation is a commonly explored technique for promoting active and ongoing engagement with citizen science projects (Dickinson et al. 2012; Raddick et al. 2013). However, incentivising participation in citizen science projects may lead to bias (Raddick et al. 2013), and previous research has suggested that incentivisation is not a key motivating factor driving FrogID involvement (Thompson et al. 2023). As the FrogID Audio Analysis dataset was geographically restricted to the Sydney GCCSA, it may have been useful to explore active promotion of the project specifically within the Sydney GCCSA. Such geographically targeted promotion may have incited local interest and participation from volunteers with local knowledge of frog species within the region, potentially heightening the local relevance of the project. Future research should strategically target promotion and outreach to maximise engagement and local relevance of citizen science projects.

Conclusions

Crowdsourcing species identification is an effective tool for processing large quantities of citizen science data whilst engaging the broader public in the scientific process. Our evaluation of the FrogID Audio Analysis project demonstrates the considerable challenges posed by identifying species from audio recordings, particularly in cases where multiple species are present. Although the accuracy of volunteer responses was low, aggregating volunteer responses resulted in increased identification accuracy. A number of alternative methods to enhance data quality exist, including the incorporation of training and feedback, weighting volunteer responses according to individual skill level, implementing targeted engagement strategies, and developing intuitive user interface designs.

Data Accessibility Statement

Data were analysed and figures produced using R (R Core Team 2020). In accordance with the ethics guidelines outlined by the Human Ethics Committee approval (HC220327), the authors do not have permission to share the data used in this study.

Supplemental Files

The Supplemental Files for this article can be found as follows:

Ethics and Consent

This research was approved by the Human Ethics Committee at the University of New South Wales, Sydney (Reference Number – HC220327).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Citizen Science Grants of the Australian Government and the Impact Grants program of IBM Australia for providing funding and resources to help build the initial FrogID App; the generous donors who have provided funding for the project including the James Kirby Foundation; the NSW Biodiversity Conservation Trust and the Department of Planning and Environment – Water, and the Saving our Species program as Supporting Partners; the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory, Museums Victoria, Queensland Museum, South Australian Museum, Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, and Western Australian Museum as FrogID partner museums; the many Australian Museum staff and volunteers who make up the FrogID team; and, most importantly, the thousands of citizen scientists across Australia who have volunteered their time to record frogs.

Additionally, we would like to thank the 233 citizen scientists who took part in the FrogID Audio Analysis Trials. This work would not have been possible without the time and skills each citizen scientist contributed to the project, offering valuable insights into the parameters required for crowd-sourced FrogID validation whilst upholding scientific rigour. We would also like to acknowledge that the findings of this paper are not a reflection of the capacity or willingness of citizen scientists to contribute to frog identification. Rather, this study has reinforced our understanding that the identification of frog species from FrogID audio recordings is a particularly challenging task, and will require us to continue exploring a range of approaches.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Author Contributions

PF, NR, AW and JR contributed to study conceptualisation and data collection. GG and JR conducted data analysis and manuscript writing. All authors contributed equally to the revising of the manuscript.