Research Question

How early should students be exposed to scientific knowledge, skills, and experience with research methodologies? This is important because research by Oliveira et al. 2023 shows that there is a lack of science education in elementary schools. While the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) and California Science Framework provide curricular guidelines, instructional minutes for science in elementary school vary widely. This lack of science education in elementary schools can have long-term effects on students’ attitudes towards science and their ability to effectively communicate scientific information. Oliveira notes, “a critical aspect of improving students’ science oracy skills is helping them develop more informed understandings of the nature of science communication.” Providing a comprehensive science education enhances the potential growth and effectiveness of future scientists and leaders in STEM fields. There is a need in our education system to create a pipeline early in K–12 that can lead to education and career choices in STEM. To ensure a capable STEM workforce in the future and to bridge knowledge and skills gaps for students, schools partnering with marine science institutions provide experiences to develop ocean literacy.

This research seeks 1) to shed light on how much “authentic science” practices are shared with the public, in particular, with elementary students, by surveying institutions about what they have done in this effort and how much students recall about their early exposure, and 2) to uncover how important this earlier exposure to general science is, simply by asking students their opinions regarding impact as well as correlating their choice of majors with the timing of their science education. A secondary idea that may be important is whether students can be greatly influenced by the role models that they are exposed to. This particular research project targeted both science majors and non-science majors at CSUMB, with the intention of doing a second research project that expands to include other colleges for both science and non-science majors, as it may turn out that CSUMB attracts students with a particular interest in science due to its location.

Does early exposure impact students as they choose their college majors? The choice of college major influences students’ future career choices and ultimately the STEM workforce.

Introduction

The ocean faces numerous threats such as climate change, overfishing, and pollution, which demand immediate action to improve understanding and pursue sustainable management (Kelly et al. 2022). Public awareness and engagement are crucial for fostering pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors, as well as attracting new talent into fields like Marine Science and Biology. A lack of public education, particularly among younger generations, has been identified as a key driver of issues like marine debris (Herdiansyah et al. 2021; Purba et al. 2023).

Educational outreach, such as school programs, community events, and citizen science initiatives, has proven effective in raising awareness and inspiring behavioral changes. For example, studies on coastal cleanups emphasize the importance of community participation in addressing marine pollution and collecting valuable data (Purba et al. 2023). Similarly, Van der Velde et al. (2017) found that citizen science not only produces high-quality data but also promotes environmental education and collaboration among stakeholders, leading to more effective solutions. Supported by a variety of stakeholders, including local communities, NGOs, and government agencies (Purba et al. 2023), these cleanup efforts are an example of the connection between action, ocean literacy, and science education outreach.

While most authors refer to the need for awareness and education, specifics are left for institutions, colleges, and schools to solve. According to Olivera, clearer scientific information that is accessible and compelling can lead to better multidirectional communication between scientists and nonscientists (Olivera et al. 2023). This can break down barriers between academic, public, and political communities, narrowing the gap between scientific research and real-world applications. In order to achieve this, science education must focus not only on teaching students the content of scientific concepts, but also on how to effectively communicate and apply those concepts in real-world situations. Olivera points out that students’ views of science and science communication often remain naive and unchecked. This suggests why it’s crucial to connect institutions of research with students; such engagement will help students develop more informed understandings. Equipped with a deeper understanding, students can more effectively communicate scientific information to their peers and other students in the future.

Schaen and colleagues’ research on the alignment of science education with the Next Generation Science Standards identifies a key element of the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) includes students engaging in authentic science and engineering practices that scientists and engineers perform in their jobs (NGSS Lead States 2013; Schaen et al. 2023). In the context of science, it is important to provide students with hands-on and field-based experiences in addition to traditional classroom learning. For example, when students collect and analyze data using an iPad for taking pictures and recording observations of insects visiting the garden and then learn how to write letters explaining why their school needs a garden, they gain a sense of purpose and real-life application of their scientific knowledge.

The growing demand for a skilled STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) workforce highlights the importance of understanding the factors that influence students’ decisions to pursue STEM majors. The exposure to math and science courses, along with the support from academic interactions, financial aid, and college readiness, can play a pivotal role in fostering positive attitudes and self-efficacy during high school. Additionally, aligning educational practices with real-world applications and providing equitable and robust support systems can inspire and sustain interest in STEM fields (Wang et al. 2013). Focusing on science exposure in early elementary school represents a novel approach that targets the development of science and engineering practices, in contrast to prior research that has largely emphasized exposure during high school or near-college years.

Methodology

Two surveys were developed: 1) one for the institutions that potentially offer marine science education and/or outreach and 2) one for college students. Ideally, institutions could be any organization with a mission to educate K-12 students, which could include aquariums, research institutes, public and private schools with the National Atmospheric and Oceanic Administration (NOAA) Ocean Guardian programs, non-profits such as Save the Whales, etc. This particular research focused exclusively on independent nonprofits doing research in marine science. While this is a significant limitation, it still provides important insights while leaving room for expanding the research in a future study. Also, by asking students where and when they recall having been exposed to science education, we indirectly expand the set of institutions being considered. However, it would be preferable to expand both sets of data, student and institution. Both surveys can be used again for expanded pools of respondents without changing the survey formats and questions.

This study was conducted with approval from the Internal Review Board for Human Subjects at California State University Monterey Bay, as exempt research, according to 45 CFR Part 690.101.

Institution Survey

The institution surveys were sent to a number of institutions for feedback before a survey design was finalized. The survey questions were also reviewed by subject matter experts in marine science education to confirm their relevance and alignment with the research objectives. Both the institution survey and student survey were sent to the IRB for review. Additionally, pilot testing was conducted with a small group of participants from institutions to refine the questions, ensuring clarity and reducing potential biases. To enhance reliability, a single survey was designed to be used across various institutions in order to standardize the experience and ensure consistent wording and structure across all participants. This approach minimizes variability in how respondents interpret and answer the questions. For the institutional survey, the three sections were designed to accommodate any type of institution and systematically address key areas of focus, ensuring comprehensive and consistent data collection across all participating organizations. The three sections in the survey for institutions that work with marine science education and/or outreach included: 1) understanding the areas of focus of the organization, 2) the extent of education and outreach efforts (topics and depth), and 3) the impact and reach of the education and outreach (ages, diverse cultures, economic levels, locations, methodology, standards, timing). In part 2 of the survey, the focus was primarily on programs that impact preschool through 5th grade students (TK–5th graders) to measure the relative focus on early education.

Undergraduate Survey

To establish the cognitive validity of the survey questions, the authors conducted a series of think-aloud interviews with a total of 22 undergraduates to ensure that students understood what each question was asking. The survey was iteratively revised after each think-aloud interview until the questions were fully understood by the interviewees. To check if survey answers were reliable, undergraduates were asked the same questions again two weeks after the first implementation of the survey (Tourangeau 2020). Then, researchers compared the two sets of answers. The authors added some questions regarding their understanding of the ocean to uncover a secondary effect regarding attitudes. Using the gross difference rate (GDR), which shows the percentage of people who gave different answers the second time compared to the first time, none of the individuals interviewed gave different responses. To correct for chance agreement, the researchers also calculated Cohen’s kappa (Cohen 1960). The student survey allowed for a diverse range of majors and college grade levels to capture a broad spectrum of experiences, increasing the generalizability of the findings. The survey for college students had responses from a variety of majors, including marine science students at California State University Monterey Bay (CSUMB), as well as non-science majors such as Communications, Psychology, and Visual and Performing Arts. The questions posed were designed to gather data on when and where they first were exposed to science education, what their recollections were of those experiences, and how they think their decisions were impacted to pursue their major.

Participants

There were 100 students who consented and responded to the survey. Of the respondents 94% were STEM majors (n = 100). This limited population does not fully reflect the population of CSUMB, but this may still be a large enough pool to see whether the results are consistent between the STEM group and non-STEM group. Data for gender and ethnicity was not collected as part of this survey, so we note that the general population of students at CSUMB and in the College of Science as of Spring 2025 was 61% female, 39% male, and 1% nonbinary. The ethnicity of CSUMB students includes: African American 3%, Asian American 8%, Latino 48%, Native American 1%, other/decline 3%, Pacific Islander 1%, two or more races 8%, white 29% (CSUMB IAR, 2025).

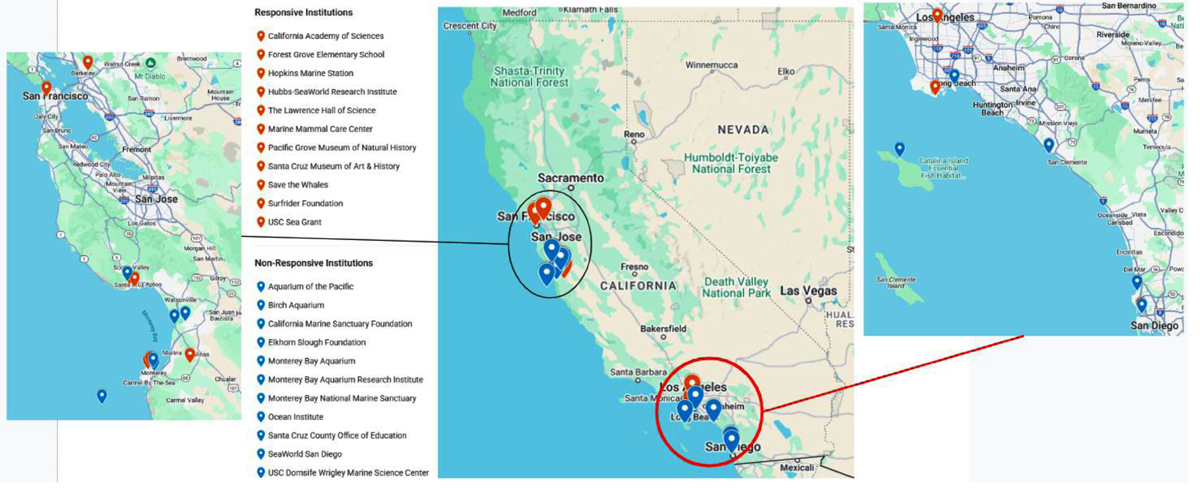

There were 21 Institutions with marine science outreach programs that were sent surveys shown below in the map (Figure 1) and below in Table 1 are the eleven that responded.

Figure 1

Map of Ocean Outreach Institutions (Red are responders, Blue are non-responders).

Table 1

Institutions Surveyed for Science Education Outreach.

| INSTITUTION NAME | LINK |

|---|---|

| California Academy of Sciences | https://www.calacademy.org/ |

| An aquarium, planetarium, rainforest, and natural history museum in the heart of San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park—and a powerful voice for biodiversity research and exploration, environmental education, and sustainability across the globe. | |

| Hopkins Marine Station and Stanford Center for Ocean Solutions | https://hopkinsmarinestation.stanford.edu/ |

| Hopkins Marine Station is the marine laboratory of Stanford University. It is located ninety miles south of the university’s main campus, in Pacific Grove, California on the Monterey Peninsula | |

| Hubbs-SeaWorld Research Institute | https://hswri.org/education-and-outreach/ |

| Hubbs SeaWord is a scientific research organization committed to conserving and renewing marine life to ensure a healthier planet. A team of experts provides innovative and objective scientific solutions to challenges threatening ocean health and marine life in our rapidly changing world. | |

| Lawrence Hall of Science | https://lawrencehallofscience.org/ |

| A public science center at the University of California, Berkeley that aims to make science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) accessible to all. The center is known for its innovative programs, exhibits, and resources for educators and policymakers. | |

| Marine Mammal Care Center | https://marinemammalcare.org/ |

| The Marine Mammal Care Center is a non-profit organization that inspires ocean conservation through marine mammal rescue (mainly seals and sea lions) and rehabilitation, education, and research. They respond to marine mammals in distress year-round, and they have a S.E.A. Lab (Science, Exploration, and Action for Ocean Conservation), which is a hands-on STEM program that immerses participants in marine science through interactive activities. | |

| Ocean Guardian Program | https://sanctuaries.noaa.gov/education/ocean_guardian/ |

| This program encourages children to explore their natural surroundings to form a sense of personal connection to the ocean and/or watersheds in which they live. | |

| Pacific Grove Museum of Natural History | https://www.pgmuseum.org/ |

| The Pacific Grove Museum of Natural History is an award-winning museum that opened in 1883, making it one of the oldest natural history museums in the United States. The museum’s mission is to inspire people to explore and protect the natural and cultural wonders of the Central California Coast. | |

| Santa Cruz Museum of Natural History | https://www.santacruzmuseum.org/ |

| The Santa Cruz Museum of Natural History (MNHC) is a nonprofit organization that aims to connect people with nature and science, and inspire stewardship of the natural world. The museum’s exhibits and educational programs focus on the natural and cultural history of the Monterey Bay region, from the shoreline to the Santa Cruz Mountains. | |

| Save the Whales | https://savethewhales.org/ |

| A nonprofit organization that works to protect marine life and the ocean. Founded in 1977 by Maris Sidenstecker, the organization focuses on educating the public, especially children, about marine mammals and the ocean environment. They believe that children can promote change and that education is key to saving the ocean and whales. | |

| Surfrider Foundation Monterey County | https://www.surfrider.org/ |

| The Surfrider Foundation is a non-profit organization that works to protect and preserve the world’s oceans, waves, and beaches. Founded in 1984 by surfers in Malibu, California, the organization has over 50,000 members and 90 chapters worldwide. | |

| University of Southern California Sea Grant | https://seagrant.noaa.gov/ |

| Sea Grant is a federal-university partnership program that works to create and maintain a healthy coastal environment and economy. The program was established by the U.S. Congress in 1966 and is inspired by the success of the Land Grant Program. Sea Grant’s network includes 34 university-based programs, the National Sea Grant Library, and hundreds of research institutions. | |

Statistical Analysis Methods

For the student responses, this study focused on the relationship between the College Majors the students chose and the earliest age group they recall learning about science. For this focus, the Chi-Square test was used since both the college major and the age reference are categorical data sets. For the institution data, the Chi-Square test was not used due to the small number of institutions surveyed, and descriptive statistics were used for analysis.

Steps to Check Chi-Square Test Assumptions:

Categorical data: Both variables (Student’s Major and Earliest Age) are categorical.

Independent Observations: Each student response belongs to only one major and one earliest age category, so they are independent of each other.

Mutually Exclusive Cells: Each student is assigned to only one category of the earliest age column, so this assumption is met.

Expected Frequency ≥ 5: The frequency for each student was expected to be at least 5 for the group of STEM majors, but not for the group of non-STEM majors.

If the data set does not match the assumptions to determine if a Chi-Square test is appropriate, an alternative test would be a Fisher’s Exact test (Table 2). Both the Chi-Square test and Fisher’s Exact test were used to evaluate whether there is a significant association between two categorical variables, as summarized in a contingency table. The choice between the two depended on sample size and expected cell frequencies. When any expected cell frequency was below five, the Chi-Square approximation to the true probability distribution became unreliable. The Fisher’s Exact test computed the exact probability of observing the data assuming no association between variables. It is particularly appropriate when sample sizes are small or when expected frequencies in one or more cells are less than five.

Table 2

Comparison between the Chi-Square test and Fisher’s Exact Test.

| FEATURE | CHI-SQUARE TEST | FISHER’S EXACT TEST |

|---|---|---|

| Assumptions | Expected counts ≥ 5 in most cells | No minimum expected count requirement |

| Method | Approximate test (uses chi-squared distribution) | Exact test (calculates true probabilities) |

| Best for | Larger samples with balanced data | Small or sparse samples, especially with many 0 s |

| Performance | Fast, even on large tables | Slower on large tables, may not run on big ones |

Null hypothesis: There is no significant relationship between a student’s major and their earliest age of enrollment.

Alternative hypothesis: There is a significant relationship between a student’s major and their earliest age of enrollment.

With the statistical analysis methods established, including the use of Chi-Square and Fisher’s Exact tests to evaluate the relationship between students’ earliest exposure to science and their choice of college majors, the study reports findings which address the central research question, “How does the timing of early science exposure influence students’ decisions to pursue STEM majors?”, providing valuable insights into the role of early education in shaping academic and career pathways.

Findings

The following section presents the outcomes of both surveys, highlighting institutional focus with students’ recollections of early exposure.

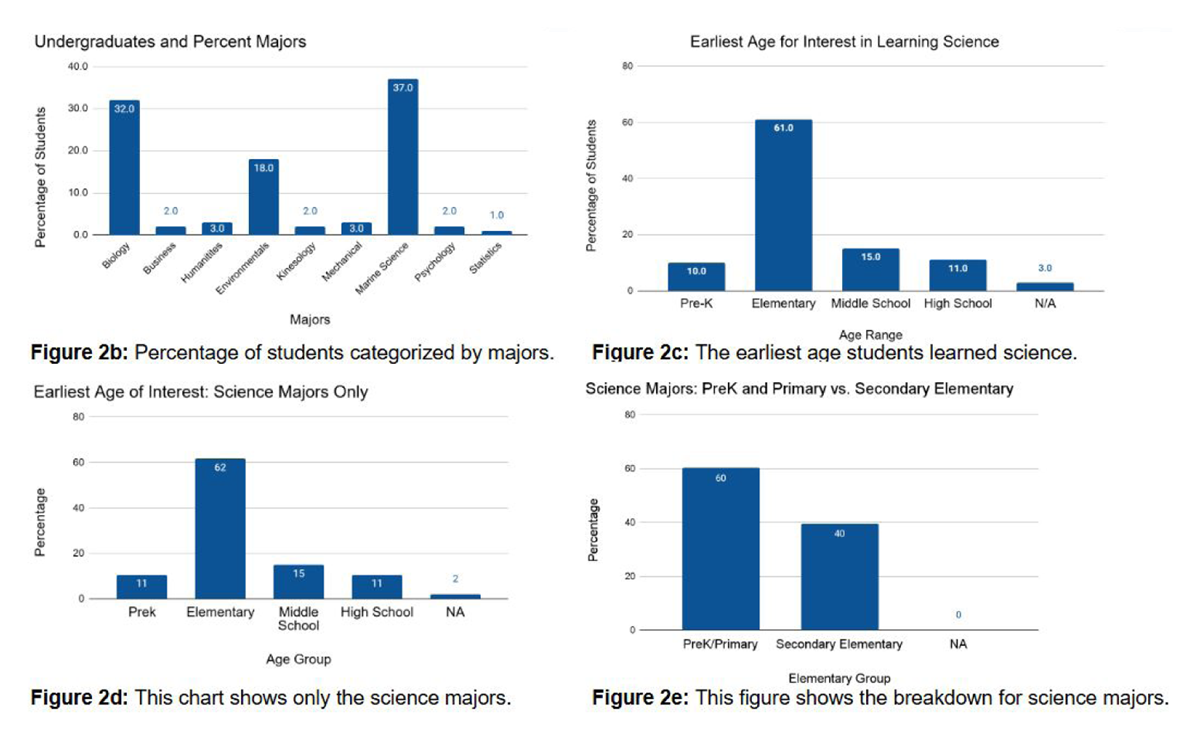

Undergraduate Survey

100 undergraduate students responded to the survey. In Figure 2b, notice that over 80% of the majors were some combination of biology, environmental science, and marine science. In Figure 2c, almost every single student recalls an early experience. The two cases where they indicated an NA was because they could not pinpoint a time, but in their comments, they explained that in one case they felt their experience was from birth because their parents were into science and, in the other case, they recall reading a science book at an early age. Over 69% indicated being influenced in the PreK–5 years.

Based on the Chi Square test, there is a significant relationship between a student’s choice of college majors and the earliest age they recall learning about Science (p = 0.004551). We also used a Fisher test for the majors with a very small number of responses (Table 3): Business, Humanities, Kinesiology, Psychology, and Statistics. Based on the Fisher test for that group of majors, there is still a significant relationship between a student’s choice of college majors and the earliest age they recall learning about Science (p = 0.02762). Without exposure to science, students are unlikely to choose science majors. A further area for research could be the selection of majors across different disciplines, whereas this article mainly focused on science majors.

Table 3

Student responses by major and earliest grade level recalling Science learning.

| MAJORS/GRADES | PREK | ELEMENTARY | MIDDLE_SCHOOL | HIGH_SCHOOL | N/A | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Studies | 4 | 21 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 32 |

| Business and Marketing | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Environmental Studies/Science | 2 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 18 |

| Humanities | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Kinesology | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Mechanical | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Marine Science | 4 | 26 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 37 |

| Psychology | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Statistics | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| TOTAL | 10 | 61 | 15 | 11 | 3 | 100 |

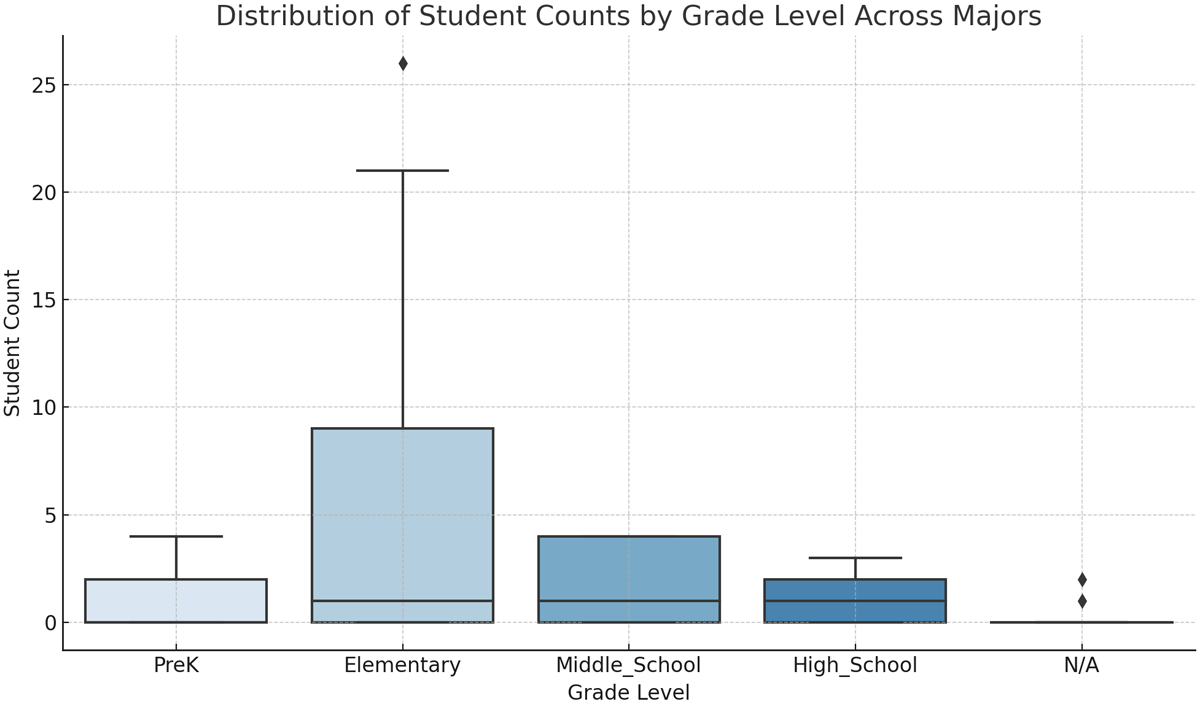

In reviewing all student responses, most students recall exposure in PreK–5. Fewer students reference science exposure in middle and high school (Figure 2a).

Figure 2a

Box Plot of Students and Exposure to Science. This box plot indicates how many undergraduate students were first exposed to science by grade level. The highest number of students selected elementary (K-5) as their early exposure to science.

Focusing only on the Science majors, a total of 73%, indicated being influenced in the PreK to Elementary years. If we break that down even further, over 60% indicated being influenced in the PreK–5 years (PreK –2nd grade) (Figure 2d and 2e).

Figures 2b–2e

Summary of responses from undergraduates surveyed.

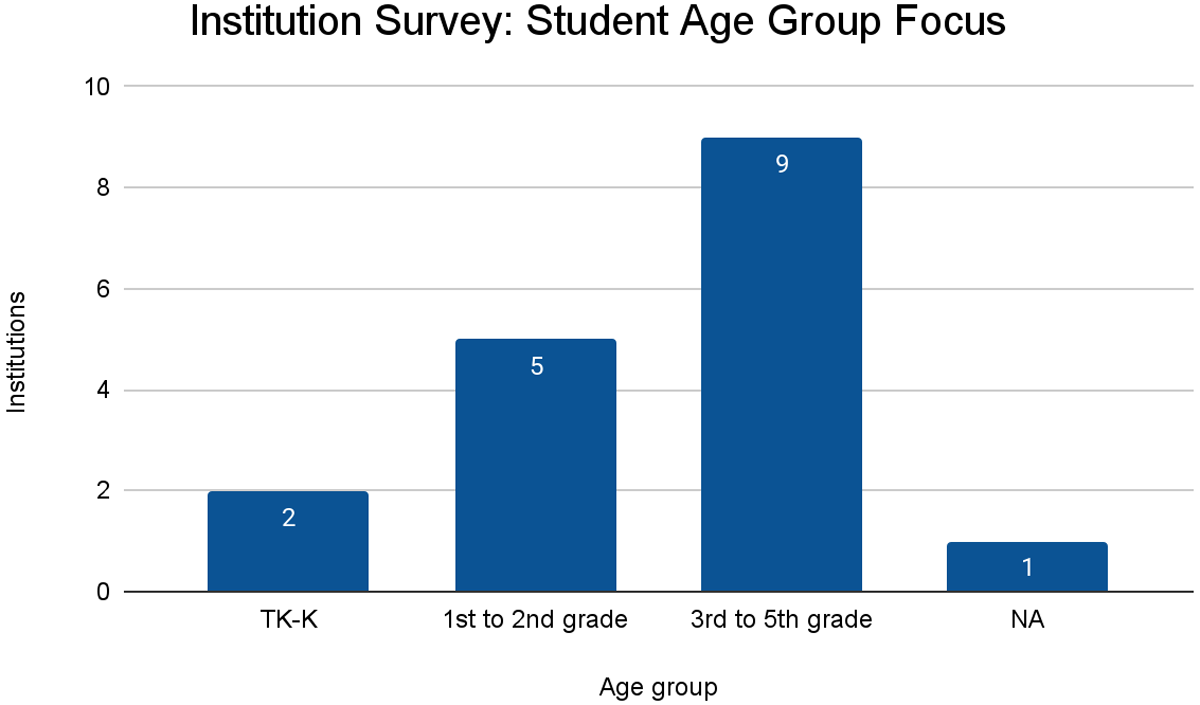

Institutions Survey

When looking at the institution data, this study found that institutional education/outreach focused mainly on the secondary elementary group (3rd–5th grade). 53% of the institutional programming focused on the secondary elementary, 41% focused on the PreK–5, and 8% said they did not address PreK–5 at all (Figure 3a).

Figure 3a

11 Institutions were surveyed. This graph shows that 9 of the 11 (81%) targeted 3rd to 5th graders. Only 5 institutions of the 11 targeted 1st to 2nd grade and only 2 targeted TK–K.

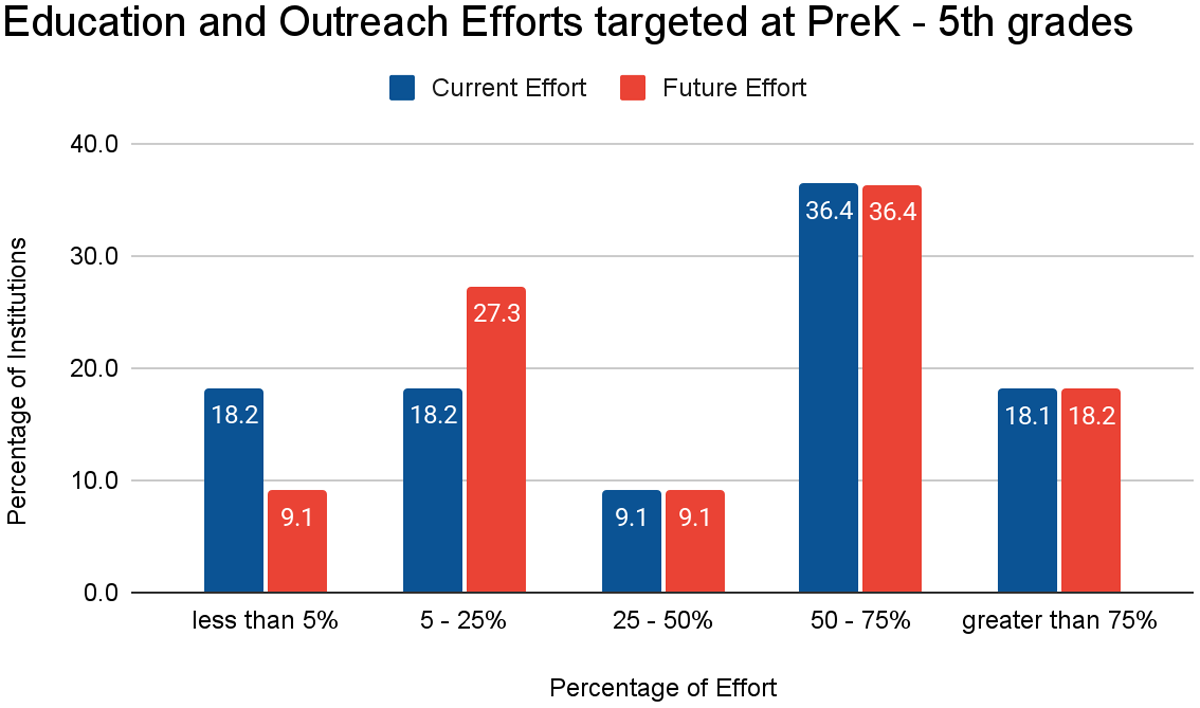

Figure 3b

The percent of effort by institutions (out of 11) targeting PreK–5th grade students when it comes to education and outreach. The blue bars represent the current effort by institutions to target PreK–5th grade, while the red bars represent the future effort or the intention to target PreK–5th grade. While almost all institutions do some outreach in the PreK to 5th grade, about 46% spent less than 50% of their outreach efforts in this age group.

Discussion

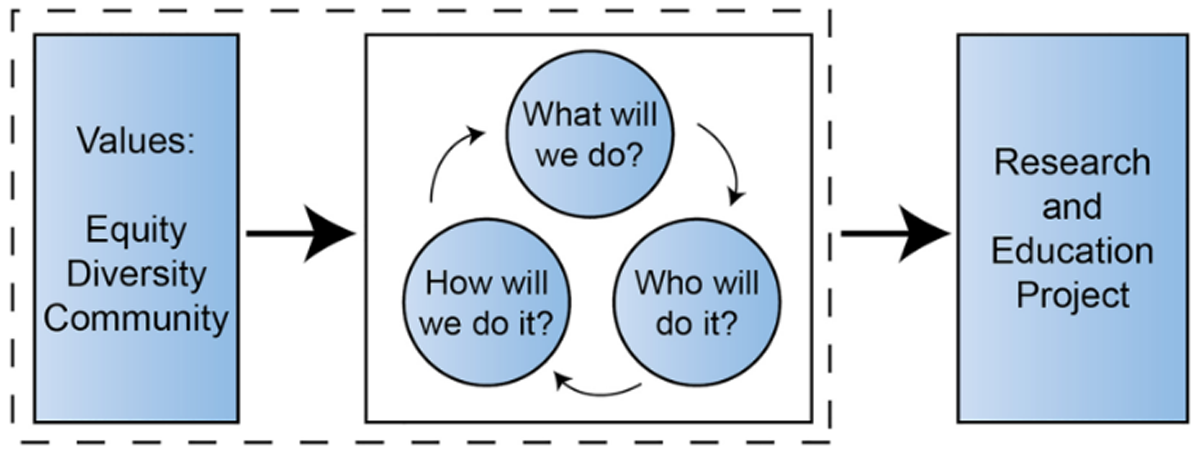

The motivation for this study was the authors’ desire to improve the community’s effectiveness in learning about and protecting the environment. As Herdiansyah et al. (2021) point out, the problems are in fact complex and nuanced. Figure 4 below illustrates how this concern leads to asking the question “who will do it?” Understanding what leads students to have a passion for science, enough to make them enroll in specific college major, and pursue STEM as a career, can help us proactively increase the number of people in the community who can take action.

Figure 4

Schematic depiction of values as the overarching guidance for decisions in research and education that can guide research or education projects in alignment with these values (Perdrial et al. 2023).

The findings from the undergraduate survey and the institutional responses reveal a shared emphasis on the importance of early exposure to science, particularly in fostering interest and positive attitudes toward environmental and marine issues. However, there are notable differences in the exact timing and methods of exposure highlighted by the two groups.

From the undergraduate survey, a significant majority (62%) of students reported their first encounter with science occurred in elementary school, with an additional 11% exposed even earlier, in Pre–K (Figure 2d). Among the science majors that indicated learning about science in K–5, the vast majority were in the PreK–2 (Figure 2e). Their exposure to science can come from family members or their friends who are scientists, teachers, and/or health care providers. The statistical analysis validates that there is a significant relationship between a student’s choice of college majors and the earliest age they recall learning about science. This was also true for the non-science majors despite the fact that there was a very small number of responses. Without exposure to science, the data shows that students are unlikely to choose science majors.

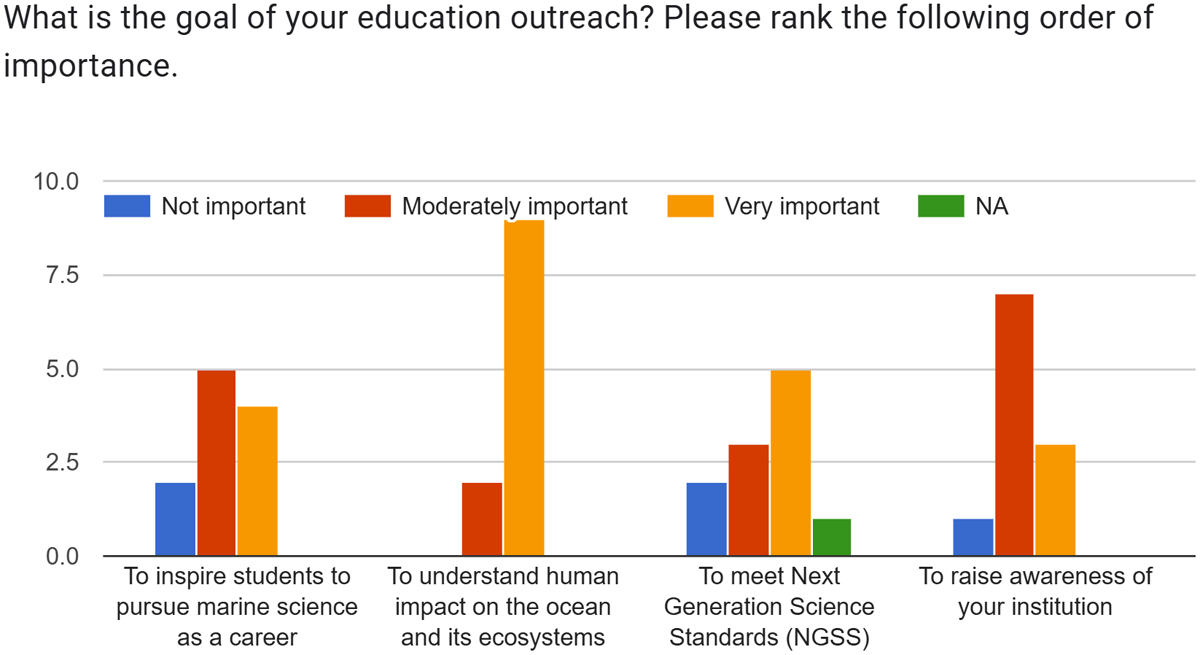

Institutions, on the other hand, appear to recognize the importance of targeting younger audiences, but their effort is not as well aligned as it could be to affect student impact. The institutions clearly lean towards 3rd–5th over PreK–2 with 81% of the institutions surveyed offering programs for upper elementary (3rd to 5th grade), but only 45% targeted primary elementary and only 2 institutions targeted PreK–K, representing only 18% of the respondents (Figure 3a). Furthermore, in Figure 3b, the blue bars indicate that currently, more than 36% only direct a small amount of their effort to the entire PreK to 5th grade (less than 25%). Based on their future outlook, the red bars, this is largely unchanged with a slight uptick in effort. This may mean that even though they think they are addressing the elementary segment, they could be starting earlier and doing more. This may represent a missed opportunity to influence students. This result along with the undergraduate findings highlights a shared understanding of the formative impact of early science education, but there is clearly room for improvement. There may actually be a lack of ambition or understanding by the institutions when it comes to trying to impact student choices. Below is a graph that shows that institutions are focused much more on environmental awareness than on student choices of study (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Institutional survey of goals of education and outreach.

Institutions emphasize hands-on learning experiences, such as visiting aquariums and engaging with live animals, as effective methods for fostering curiosity and environmental literacy among young learners. Young learners are especially receptive to new ideas, introducing topics such as marine science “needs to start in childhood when logical minds and creative imaginations are most open to new and exciting ideas” (Joyce et al. 2019). This is reflected in our institutional survey results, where only one institution did not target elementary ages, while over 40% of institutions focused more than half of their outreach efforts on younger students (PreK-5th grade). These efforts align with the understanding that early education is a pivotal time for developing pro-environmental values and scientific curiosity, with ripple effects extending to families, communities, and broader societal approaches to sustainability (Joyce et al. 2019).

However, the role of educators and scientists as role models cannot be overlooked. Oliveira et al. (2023) found that while students improved their verbal communication skills after engaging with scientific research, gaps remained in visual communication, reflecting the limitations of the scientists themselves. This underscores the importance of role models, both positive and negative, in shaping students’ perceptions of science.

Citizen science has emerged as a powerful tool for engaging younger audiences, expanding research capacity, and fostering environmental stewardship. By involving participants of all ages and backgrounds, it not only generates high-quality data but also promotes education, raising awareness of issues such as marine debris, and inspires behavioral change (Van der Velde et al. 2017). Effective implementation requires that institutions design educational programs with clear goals and approaches tailored to the developmental needs of children, as feedback from oceanic institutions highlights the importance of aligning outreach with youth engagement. As Qu et al. (2023) noted, “the young generation is a key stakeholder not only bearing the burden of past and present environmental issues but also with the responsibility of responding to and coping with future environmental issues… school is a critical period for the formation of values as well as environmental literacy.” Moreover, citizen science encourages collaboration among government agencies, non-profit organizations, and local communities, strengthening collective efforts toward more effective conservation policies and sustainable environmental solutions.

Ocean literacy, as Kelly et al. (2022) noted, extends beyond knowledge to encompass attitudes, behaviors, and communication skills. While the 11 institutions surveyed were primarily located on the West Coast of the United States, it would be valuable to explore how regional and cultural contexts influence ocean literacy efforts. Incorporating ocean literacy into policies and engaging both young people and adults is essential for driving meaningful change. Adults, as decision-makers and voters, play a crucial role in supporting the younger generation’s efforts to create a more sustainable future (Kelly et al. 2022).

While introductory courses at the community college level further engage students and foster interest in these fields, Evans et al. (2020) found that math self-efficacy and advanced math coursework in high school are key factors influencing students’ decisions to pursue STEM majors. Community colleges, with their open access and affordability, are uniquely positioned to address these challenges and serve as a gateway for students who might otherwise lack access to STEM education. Nearly half of all students earning bachelor’s or master’s degrees in science and engineering attend community colleges at some point, making these institutions vital for meeting the nation’s STEM workforce demands. By enhancing math and science preparation, creating supportive learning environments, community colleges can play a pivotal role in fostering a more diverse and capable STEM workforce (Evans et al. 2020). Community colleges build on existing student interest that is fostered by early experiences.

When considering the undergraduate student population, the diversity of students surveyed could be another reason why science is not reaching some students. Historical barriers, such as systemic racism, have excluded underrepresented groups such as African Americans, Hispanics, Native Americans, LGBTQ+, women, and people with disabilities from meaningful participation in STEM fields (Perdrial et al. 2023). Increasing diversity in STEM is not only a matter of equity but also a driver of innovation and problem-solving. Diverse teams bring a broader range of perspectives and approaches, leading to more creative and impactful outcomes (Cheruvelil et al. 2014; Yang et al. 2022). Addressing these disparities and creating inclusive pathways into STEM fields is essential for fostering a workforce capable of tackling complex environmental challenges.

Both the undergraduate and institutional findings emphasize the need for continued efforts to expand access to science education, particularly for underrepresented groups and those who encounter science later in life. Institutions must also address broader challenges, such as disparities in ocean literacy between developed and developing countries, and the need to involve adults in ocean education to drive systemic change. By incorporating diverse perspectives and addressing these limitations, future outreach and education programs can better support the next generation of informed and responsible ocean stewards.

We report here the findings from the undergraduate survey and a group of selected mid-size public institutions on the West Coast. A next phase of research could include additional oceanic science institutions both inside and outside California and the United States. Additional student responses from different universities, and ideally also community colleges would be beneficial to augment these initial findings. It would be useful to survey undergraduates who plan to go into ocean education and outreach careers to learn how they determined their academic pathways and career plan. Themes from student responses include early fascination with plants, animals, and ecosystems through direct encounters with life sciences. In particular, exposure to marine environments and ocean organisms were early motivators for science interest for current science majors. Students found engagement with science through experiments, models, and experiences, which stimulated their curiosity.

Recommendations

These preliminary findings indicate that there is room for institutions to better align their focus with students. They might consider shifting programming earlier, beginning with PreK, given students are clearly open to learning about science. Our survey of students shows that they remember those years. A significant number of students could recall being exposed to science as early as the age of 4. One student commented, “Any experience when I was young always filled me with wonder and made the world a bit bigger.”

The student survey also highlighted the importance of hands-on activities in shaping students’ attitudes toward marine science. Students who participated in such activities were more likely to express positive views, reinforcing the value of experiential learning. This finding echoes Schaen et al. (2023), who emphasized that authentic scientific practices enhance student engagement and interest by demonstrating the real-world relevance of their learning. The connections to the Next Generation Science Standards, the California Framework, and Ocean Literacy are profound. Here are three examples: A comprehensive understanding of biogeology and human impacts on Earth systems (DCI ESS2.E, ESS3.C) must include the ways in which humans influence the ocean. The remarkable diversity of major ocean organisms illustrates key biological concepts of inheritance, variation, and diversity (DCI LS3.A, B). However, human activities such as coastal development, pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, and overfishing have significantly affected ocean systems, altering biological diversity and contributing to species extinctions. NGSS K-ESS3-3 epitomizes the focus on students communicating solutions that reduce the impact of humans on the land, water, air, and other living things.

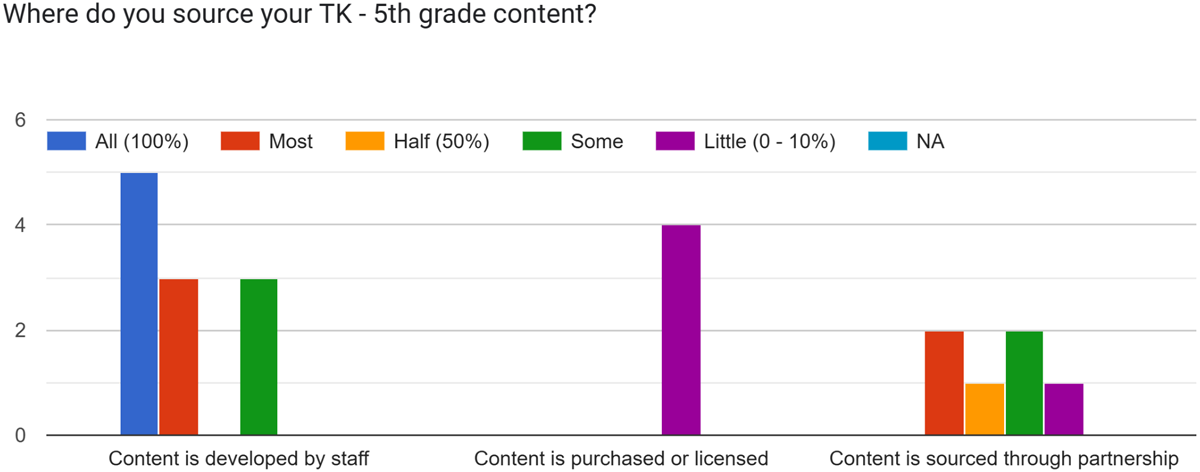

Based on the results of this research, we recommend that when institutions consider emphasizing more their objectives in terms of influencing student careers and placing equal focus on the early childhood exposure starting with PreK. If institutions are looking for immediate impact, that is more likely to be achieved by engaging adults alongside their students. If the lack of focus in the early years is due to content, institutions might consider increasing their level of collaboration with third-party providers and community-based research partners. In Figure 6 below, we can see that institutions rely primarily on in-house staff.

Figure 6

Institutional survey of where institutions sourced their content for TK – 5th grade students.

In community-based research partnerships, traditional knowledge from Indigenous communities has proven to be invaluable to ocean literacy, especially from individuals who live close to the ocean because their identities are closely intertwined with marine environments and it can have a significant positive impact on their emotional well-being. Additionally, advancements in technology and the internet have the potential to expand access and opportunities for engagement with ocean-related matters through digital channels. For example, Kelly et al. (2022) have noted a rising trend among sustainability and marine groups utilizing games to promote pro-environmental messages and prepare individuals for necessary changes. It is worth considering, however, that virtual encounters with nature may not elicit the same sensory reactions as real-life experiences. This could potentially affect the level of emotional attachment and subsequent adoption of pro-environmental actions pertaining to the ocean (Kelly et al. 2022).

Ocean literacy is important and needs everyone’s support—from educators and community groups to consumers and policymakers (Halversen et al. 2021). To effectively promote ocean knowledge, we need to share marine science information that is easy to understand and up to date. While optimistic stories can motivate people to take action for marine issues, we also need to be realistic about the challenges we face. Marine researchers should collaborate with professional communicators to reach a wider audience. Moreover, incorporating ocean literacy into education and policies will ensure that diverse community values are considered in decision-making (Kelly et al. 2022). Finally, while technology is essential for promoting ocean literacy, the most meaningful connections come from engaging strategies that merge education, culture, technology, and knowledge sharing to inspire joint responsibility for the ocean.

Conclusion

Students are happier and do better in college when they pick a major that matches what they are truly interested in. This happiness and interest can start early with experiences in childhood. Research shows that when students are exposed early to subjects that they enjoy, like science, they choose college majors that match their interests. This match leads to greater happiness and success in school (Messerer et al. 2024; Pinxten et al. 2014). It is not merely a strong interest in a particular subject that influences their decisions to choose a fitting major, but also by the classes taken in the past, their grades, and even family encouragement and backgrounds. Helping students build their interests and confidence early, such as getting excited about science, can shape college and career choices later.

Introducing ocean education at the TK–5th grade level is essential for nurturing curiosity, literacy, and positive attitudes towards careers and science as well as issues such as those regarding the marine environment. It lays the foundation for a deeper knowledge of the ocean. Improving understanding of science can lead to a greater awareness and concern for the ocean and related environmental issues. Many non-science majors had not been exposed to science until later in their education. By introducing ocean education at an early age, children can develop a strong foundation of knowledge and curiosity about the marine environment.

Inspiring a connection with the natural world, particularly the ocean, can significantly influence academic and career choices in college students. Early exposure to science, possibly through experiences with aquariums or research institutions, may be an important factor in increasing the propensity of students to pursue science-related fields. These findings are supported by Joyce et al. (2019)’s conclusion that ocean literacy enables children to understand climate change, marine biodiversity, and sustainability, influencing not only their own attitudes and behaviors but those of their families and communities. Direct feedback from participants is vital as it helps inform and refine future actions to tackle this environmental challenge (Purba et al., 2023). We need to continue to ask students themselves what works and check to see whether institutions are serving students at the right time, right place, with the right content.

Data Accessibility Statement

The raw survey data is publicly available via a Google folder: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1AUEE6Tp3c4tNC5a6-BAvqTwDfl5-ZLm6?usp=drive_link.

Appendices

Appendix

Relevant Comments from Undergraduate Students:

“I think more students should be given the chance to learn about Marine Science at least in middle school since it’s hard to take a class that covers any Marine Science related topics since it is only occasionally mentioned in biology classes.”

“I think learning about the environment at an early age is very important. People wouldn’t appreciate things they don’t know.”

“The ocean has a HUGE impact on global welfare yet the majority of individuals outside of my major have no ideas about it. I think it is one of the easiest topics to get students interested in with all the bizarre creatures which can promote their interests in science fields, which makes it ideal for primary school teaching.”

Comments from Institutions:

“Class time is a limiting factor as public schools have to focus on subjects covered in standardized testing and in adopted standards such as NGSS, making it hard to find time for “extras” such as ocean conservation.”

“No matter where you live, everything is connected so we all affect the ocean and we all need a healthy ocean to have healthy lives!”

“The ocean needs more friends. Our actions have an impact and we can all make changes to support our ocean, waves, and beaches.”

“I believe we are inspiring children while they are young and hope that they will take the message of ocean conservation to their families and carry it throughout their lives.”

Ethics and Consent

The Institutional Review Board for CSUMB has reviewed the protocol CPHS 21-052-K122 and approved the research as Exempt, Category 2. Consent was obtained from all participants completing the Survey.

Acknowledgements

The Undergraduate Research Opportunities Center (UROC) and the faculty at California State University, Monterey Bay (CSUMB) supported my research by looking through my survey for appropriateness. I also want to thank the 11 institutions and 100 students from CSUMB for being a part of the research by answering questions in the surveys.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Author Contributions

Both authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work; the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data for the work; and the drafting and subsequent revisions of the manuscript.