Introduction

The role of science and scientific reasoning in legislative policy faces many challenges (Jamieson, Kahn & Scheufele 2017). Environmental literacy (McBride et al. 2013) is generally poor and recognized as a priority area for public education efforts (Marcinkowski et al. 2012; Visbeck 2018; Johns and Pontes 2019). Ocean literacy is foundational to environmental literacy because the ocean is the planet’s life support system providing ecological services on a global scale, regulating the distribution of heat and water that sustain the world’s terrestrial biodiversity, and incidentally, also allow for human life and civilization and the economic activities upon which we depend (Stel 2021; UNESCO 2020). The ocean is also remarkably diverse biologically, and yet also poorly understood. Recognition of both the importance of oceans and societal ignorance of ocean functions spawned an ocean literacy movement in the mid 2000s (Cava et al. 2005; Schoedinger et al. 2005), in which the seven principles of ocean literacy were articulated:

The Earth has one big ocean with many features

The ocean and life in the ocean shape the features of the Earth

The ocean is a major influence on weather and climate

The ocean made the Earth habitable

The ocean supports a great diversity of life and ecosystems

The ocean and humans are inextricably interconnected

The ocean is largely unexplored

These seven principles have been assessed on a variety of audiences in populations around the world (e.g., Plankis and Morrero 2010; Fauville et al. 2019; Mogias et al. 2019; Mokos, Realdon & Zubak Čižmek 2020; Fielding, Copley & Mills 2019) but these studies of ocean literacy are invariably conducted in coastal regions where youth have life-long direct access and familiarity with oceans.

Although the ocean performs the ecosystem services that make human economies possible (OL principle #6), the general public has only a vague awareness of this connection (Steel et al. 2005; Plankis and Morrero 2010; Visbeck 2018). Similarly, public awareness of the impact of human activities on ocean health is also low. Low awareness of the interconnectedness between ocean and human health may be especially pronounced for inland populations for whom oceans are a distant and abstract concept (Steel et al. 2005). For example, Glithero et al. (2021) divided their survey between those who self-identified as “ocean-engaged” who either directly or indirectly engaged in ocean literacy or ocean-related work versus the “general public” who did not consider themselves connected to the ocean. Inland populations with little or no direct experience with oceans may have lower ocean literacy than coastal populations because marine ecosystems may be perceived as being a distant phenomenon detached from day-to-day life (Borja et al. 2020). For example, ocean literacy may be low in the Midwest of the USA even though their agriculture-based economy depends on reliable patterns of precipitation that are ultimately regulated by oceanic phenomena.

Junior Aquarist Camp for Kids (JACK)

The Fargo-Moorhead metro area is located on the state border between North Dakota and Minnesota, 2297 km east of Pacific coast city of Seattle, 2610 km west of the Atlantic coast city of Boston, 2334 km north of the city of New Orleans on the Gulf of Mexico, and 2483 km south of Radisson, Quebec on Hudson Bay of the Arctic Ocean. Geographical isolation from the ocean makes Moorhead, MN an unlikely but ideal place to establish an oceanarium because the local population does not interact directly with the ocean. The Minnesota State University Moorhead (MSUM) Oceanarium is about 167 m2 comprising four, 3700-L concrete tanks with stingrays, horseshoe crabs, a mangrove habitat and a working tidepool system. In addition, there is a 400-L jellyfish kreisel, and various large aquaria containing a variety of echinoderms and fish, including seahorses. There is also an engagement center with a circle of benches and a large display screen and learning aids for teaching and learning about oceans. The oceanarium serves as a living laboratory for courses at MSUM, and as an outreach facility for K12 students and the general public from the surrounding area.

MSUM offers a summer program for area youth called College for Kids. In the summer of 2023, we developed a week-long workshop for the College for Kids program called Junior Aquarist Camp for Kids (JACK). We conducted pre- and post-workshop surveys on participants in JACK who attended one of three, four-day sessions. We were interested in assessing (1) the level of pre-workshop ocean literacy of local youth from the Red River Valley region, (2) the effectiveness of our workshop curriculum on improving ocean literacy and, (3) how the workshop improved attitudes toward the importance of oceans and interest in ocean-related jobs.

Materials and Methods

We collected demographic data on age, sex, the grade level they will enter in the fall, and the type of school attended (public, private, or home schooled). Because we were interested in knowing exposure of this inland populations to oceans, we asked participants if they had ever been to the ocean, with response options (a) Never, (b) Once, (c) More than once, (d) More than five times. The survey, parental consent forms, protocol and verbal assent language were reviewed and approved by the MSUM Institutional Review Board.

Development of the Ocean Literacy assessment tool

Knowledge questions (see Table 1) were taken from a list of questions provided by Chen et al. (2020). We chose this resource because the questions have been pre-vetted and validated using psychoanalytic tools to ensure reliability. We selected a subsample of 14 questions from the 84 questions listed by Chen et al. (2020), to reduce the test burden on participants aged 9–14. We selected a stratified subsample in which two questions were aligned with each of the seven principles of ocean literacy. Thus, the survey assessed ocean literacy across all seven areas while keeping the survey sufficiently short to be easily implemented during the workshop. We added two questions to assess general interest in the ocean and whether or not the ocean was viewed as relevant to future employment (Table 1).

Table 1

Survey questions used for assessing knowledge of ocean literacy. Questions were taken from questions validated by Chen et al. 2020, as indicated after each question.

| OCEAN LITERACY PRINCIPLE | QUESTION | CHOICES (* = CORRECT) |

|---|---|---|

| The Earth has one big ocean with many features | 1. Which of the following most influences the depth at which organisms live in the open ocean (away from the shoreline)? [Q#023 from Chen et al. 2020] | a. Salinity levels b. Crashing waves c. *Light levels d. Human Activity |

| 2. Where is most of the water on Earth? [Q#007 from Chen et al. 2020] | a. In the atmosphere b. In polar ice caps c. In rivers and lakes d. *In the ocean | |

| The ocean and life in the ocean shape the features of the Earth | 3. Rivers supply most of the salt to the ocean. The salt in the rivers comes from: [Q#010 from Chen et al. 2020] | a. Mountain ice melting b. *Erosion of land c. Rainfall in the rivers d. Human caused pollution |

| 4. Sea level changes have: [Q#030 from Chen et al. 2020] | a. Reversed the direction that some rivers flow b. Changed global temperatures c. *Changed the shape of the coastline d. Increased fish populations | |

| 1. The ocean is a major influence on weather and climate | 5. Because the ocean covers most of the Earth: [Q#002 from Chen et al. 2020] | a. *It has the most dominant influence of Earth’s weather and climate b. Most living things are concentrated on land c. Most of the earth is not useful for humans d. It generates most of the Earth’s greenhouse gases |

| 6. If there was no ocean, the Earth’s surface temperatures would be: [Q#039 from Chen et al. 2020] | a. *More extreme around the world b. Less extreme around the world c. Cooler in the summer and warmer in the winter d. About the same as they are now | |

| 2. The ocean made the Earth habitable | 7. Both land and ocean provide space for organisms to live. How much of Earth’s living space is found in the ocean? [Q#021 from Chen et al. 2020] | a. Only a little bit (less than 10%) b. About half (40–60%) c. More than half (60–80%) d. *Nearly all (more than 90%) |

| 8. Most rain that falls on land originally evaporated from: [Q#013 from Chen et al. 2020] | a. *The ocean near the equator b. The middle of each ocean basin c. Nearby lakes and rivers d. The nearest ocean basin | |

| The ocean supports a great diversity of life and ecosystems | 9. Which of the following is true about ecological relationships in the ocean? [Q#036 from Chen et al. 2020] | a. They are very similar to those in land, including similar food webs, life cycle, and symbiotic relationships b. They are mostly unknown since so much of the ocean has not been explored c. They are mostly very simple compared to those in land d. *There are unique features of food webs, life cycles, and symbiotic relationships in the ocean that are not found on land |

| 10. Which of the following marine ecosystems is the most important nursery areas for many marine species? [Q#026 from Chen et al. 2020] | a. Coral reefs (reefs formed by living corals) b. The deep sea (more than 100 m below the ocean surface) c. The open ocean (away from the shoreline) d. *Estuaries (where rivers meet the ocean) | |

| The ocean and humans are inextricably interconnected | 11. Absorption of carbon dioxide (CO2) by the ocean has a direct influence on which of the following? [Q#034 from Chen et al. 2020] | a. The greenhouse effect and dead zones in the ocean b. Acid rain and harmful algal blooms c. Acid rain and ocean acidification d. *The greenhouse effect and ocean acidification |

| 12. The use of satellites, buoys, and remotely-operated vehicles improve our understanding [Q#029 from Chen et al. 2020] | a. Reduce errors from human measurements of the ocean b. Cause less disturbance to the marine environment c. Are cheaper than previous tools d. *Collect much more data than scientists on ships can | |

| The ocean is largely unexplored | 13. Scientists are discovering that more species than they expected live in the deep sea. These discoveries are only being made now because: [Q#031 from Chen et al. 2020] | a. Environmental conditions are causing species to migrate to the deep sea b. Deep sea species evolve more rapidly than shallow water species c. Shallow water species have been overfished d. *Scientists are just beginning to explore the deep sea |

| 14. Which of the following is true concerning the exploration of the ocean? [Q#037 from Chen et al. 2020] | a. People have been exploring the ocean for thousands of years and most of it has been explored b. Almost all of the ocean has been explored in the last 50 years because of the new technology c. *Most of the ocean is still unexplored despite improvements in technology in the last 50 years d. Most of the ocean is still unexplored because scientists focus on the areas where most organisms live | |

| Interest question 1 | How important is the ocean to you? | 1. Not at all 2. A little 3. Some 4. Quite a bit 5. A lot 6. Mostly 7. Completely |

| Interest question 2 | Would you be interested in learning more about ocean-related jobs? | 1. Not at all 2. A little 3. Some 4. Quite a bit 5. A lot 6. Mostly 7. Completely |

Description of Ocean Literacy activities in the JACK workshop

The Junior Aquarist Camp for Kids (JACK) workshop activities were adapted from activities described by the Centers for Ocean Sciences Education Excellence (COSEE). Each session of JACK ran for four days. The day-by-day programming is described in Table 2.

Table 2

Daily programming for the 4-day Junior Aquarists Camp for Kids at the INSTITUTION Oceanarium, summer 2023.

| DAY | OCEAN LITERACY PRINCIPLE(S) | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | The Earth has one big ocean with many features | 1. Administered the pre-workshop knowledge survey 2. Covered the key features of the ocean: temperature, salinity, light levels 3. Activity: completed a scavenger hunt to orient students to the lab 4. Activity: learned about salinity and temperature |

| 2 | The ocean and life in the ocean shape the features of the Earth The ocean is a major influence on weather and climate | 1. Covered the geology of the ocean 2. Covered how rocks are formed 3. Covered how the oceans became salty 4. Covered the effect of the ocean on weather and climate 5. Activity: Sand Identification, El Niño and La Niña |

| 3 | The ocean makes the Earth habitable The ocean supports a great diversity of life and ecosystems | 1. Covered how the ocean makes the Earth habitable 2. Covered different kinds of biodiversity found in the ocean 3. Activity: Ocean zones and Tank Exploration |

| 4 | The ocean and humans are inextricably interconnected The ocean is largely unexplored | 1. Covered how oceans and humans are interconnected, as well as how the ocean is largely unexplored 2. Activity: Interactive activity on litter 3. Administered the post-workshop knowledge survey |

Data analysis

Post-pre changes in responses to interest questions and overall score on knowledge questions were compared using paired t-tests. We noticed a systematic difference in responses to the two questions, which we compared using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) using pre-workshop score as the covariate, post-workshop score as the dependent variable and question as the categorical predictor. Responses on pre- and post-workshop knowledge questions were organized into four categories:

Already knew: Answered the question correctly both on the pre-test and the post-test

Learned: Answered the question incorrectly on the pre-test but correctly on the post-test

Did not learn: Answered the question incorrectly on both the pre-test and post-test

Got confused: Answered the question correctly on the pre-test but incorrectly on the post test

We compared the seven ocean literacy principles using contingency table analyses (based on the chi-square null distribution). Similarly, the effect of categorical predictors of sex, grade level and previous experience with oceans were all compared using contingency table analyses. The correlation that appeared between pre-knowledge of learning gain was assessed using linear regression using SPSS v. 28.

Results

A total of 41 students attended the workshops, 12 in the first session, 13 in the second session and 16 in the third session. Of the 41 attendees, we secured parental consent forms from 31. Of the 31 participants, some of the survey questions were left blank thus, samples sizes for individual questions ranged from 28 to 31. Demographic descriptors of respondents were distributed evenly with respect to sex, grade level they will enter in the fall (age), and experience with oceans (see Table 3). Six participants had never been to the ocean, another nine had been to an ocean only once, and seven had been to the ocean fewer than 5 times.

Table 3

Distribution of demographic data among survey respondents with respect to grade level they will enter in the fall (Grades 4 to 8, ages 9–14 years old), sex, experience with oceans, and type of school attended.

| GR4 | GR5 | GR6 | GR7 | GR8 | TOTAL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 5 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 17 |

| Male | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 14 |

| Ocean: Never | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Ocean: Once | 3 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 9 |

| Ocean: > Once | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Ocean: > 5 times | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 9 |

| Public school | 7 | 1 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 23 |

| Private school | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 7 |

| Home schooled | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 9 | 2 | 7 | 9 | 4 | 31 |

Cronbach’s alpha for questions 1–14 was 0.78, indicating a reliable test (Cronbach 1951). Data validity for responses to individual questions scored well except for question 2, indicating either an invalid question, a weak area in pre-knowledge of participants, or ineffective instruction in the JACK curricula (Table 4).

Table 4

Tests of data validity measured as bivariate Pearson correlations between responses on individual questions and their overall score on the survey.

| AREA OF OCEAN LITERACY | QUESTION | PRE-JACK SURVEY | POST-JACK SURVEY | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p | r | p | ||

| One big ocean | 1 | 0.437 | 0.070 | 0.486 | 0.041 |

| 2 | –0.012 | 0.961 | –0.112 | 0.659 | |

| Ocean shapes Earth | 3 | 0.483 | 0.042 | 0.625 | 0.006 |

| 4 | 0.349 | 0.156 | 0.367 | 0.134 | |

| Ocean influences climate | 5 | 0.320 | 0.196 | 0.384 | 0.115 |

| 6 | 0.535 | 0.022 | 0.354 | 0.150 | |

| Ocean makes Earth habitable | 7 | 0.594 | 0.009 | 0.417 | 0.085 |

| 8 | 0.490 | 0.039 | 0.309 | 0.212 | |

| Ocean has a great diversity of life | 9 | 0.459 | 0.064 | 0.367 | 0.134 |

| 10 | 0.594 | 0.009 | 0.503 | 0.033 | |

| Ocean and humans are interconnected | 11 | –0.088 | 0.727 | 0.655 | 0.003 |

| 12 | 0.113 | 0.655 | 0.500 | 0.035 | |

| Ocean is largely unexplored | 13 | 0.529 | 0.024 | 0.574 | 0.013 |

| 14 | 0.585 | 0.011 | 0.667 | 0.003 | |

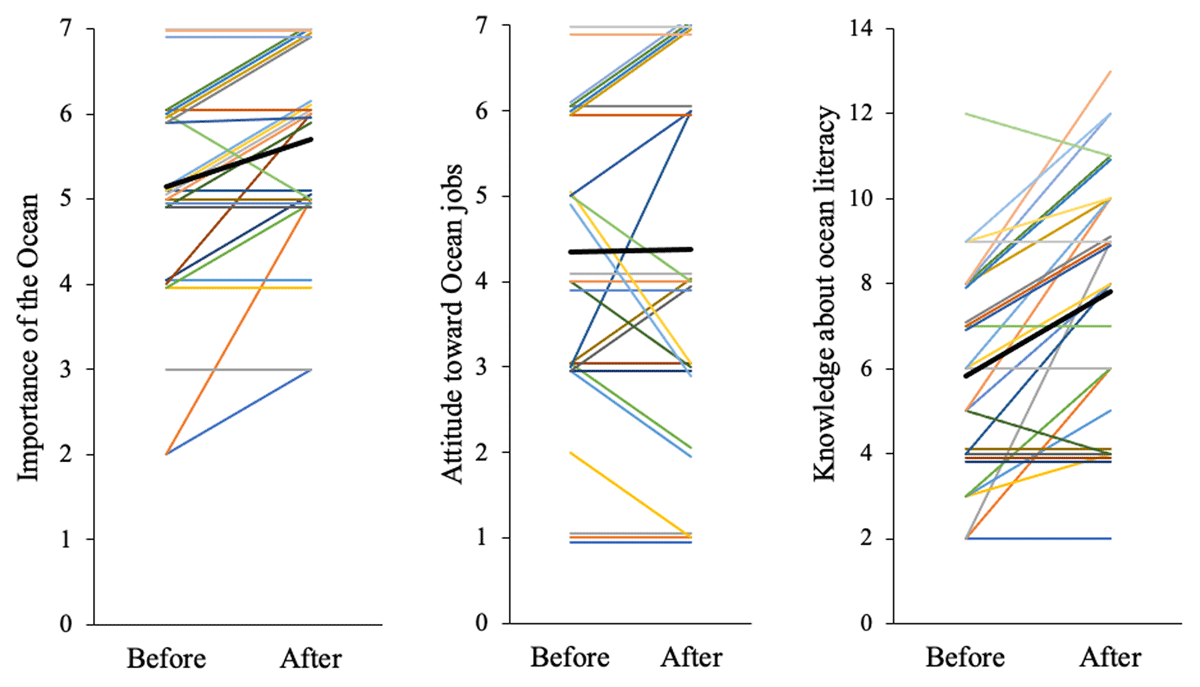

Overall, students demonstrated an increased understanding of the importance of oceans after the workshop (Cohen’s d = 0.78, paired t-test, t28 = 4.05, p < 0.001; see Figure 1A). Even though participants started with a relatively high rating of ocean importance of 5.1 out of 7, post-workshop rating of ocean importance increased further to 5.72, and that increase was consistent across the sample. In contrast, there was no consistent directional change in response to the question about interest in ocean-related jobs (4.3 before and 4.4 after, Cohen’s d = 1.02, paired t-test, t28 = 0.18, p = 0.856, see Figure 1B). Respondents that indicated high interest in ocean jobs in the pre-test tended to remain positive in the post test whereas those that were neutral to negative on the pre-test tended to decrease their rating of interest in ocean-related job on the post test. Overall, there was an increase in ocean literacy knowledge on survey scores from pre-workshop to post-workshop from 41.6 ± 3.3% (mean ± 1SE) correct on the pre-test to 55.9 ± 3.9% on the post-test (Cohen’s d = 2.00, paired t-test, t29 = 5.477, p < 0.001).

Figure 1

Individual ratings on interest questions “How important is the ocean to you?” and “Would you be interested in learning more about ocean-related jobs?” (Likert ratings: 1 = Not at all, 2 = A little, 3 = Some, 4 = Quite a bit, 5 = A lot, 6 = Mostly, 7 = Completely) and ocean literacy knowledge score before and after the JACK workshop. Heavy black lines represent mean responses. There was a significant increase in ratings for the importance of oceans and a significant increase in knowledge about the seven principles of ocean literacy.

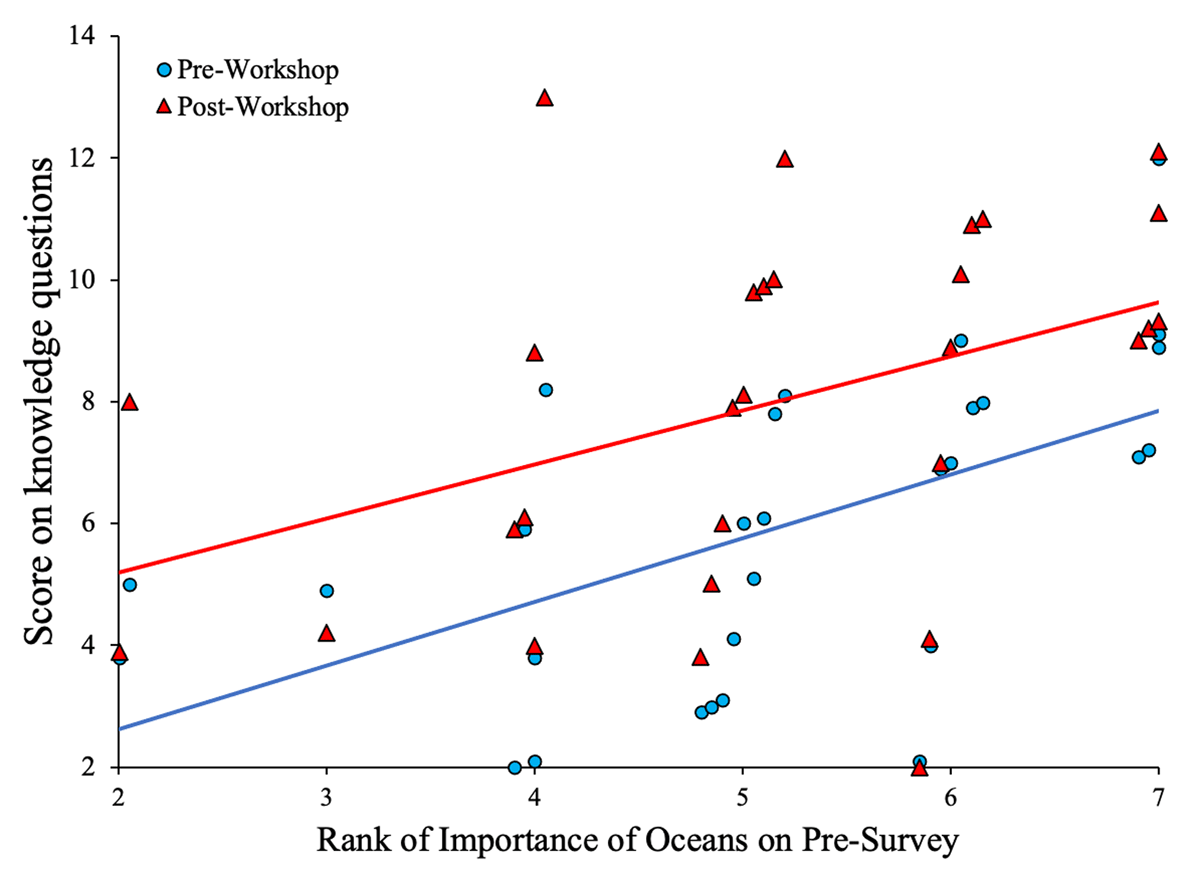

When interactions were statistically considered, the difference in responses to the two questions of general interest created a significant effect of the interaction between the effect of the workshop (post-pre) and question type (ANCOVA, question*pre-test score F1,54 = 4.44, p = 0.040, i.e., the slopes were significantly different, see Figure 2). General attitude about oceans, as measured by the pre-workshop rating to the interest question “How important are Oceans to you” was a significant predictor of score on the knowledge score on both pre-workshop and post-workshop surveys (ANCOVA, F1,54 = 11.97, p = 0.001) and but did not predict post-pre change (learning gain) in score as indicated by a non-significant interaction term (i.e., the effect of interest in oceans and test score did not depend on which test was being compared, ANCOVA pre-workshop interest in oceans * pre v post change on survey scores: F1,54 = 0.15, p = 0.696; see Figure 3).

Figure 2

Changes in ratings for ocean importance and interest in ocean jobs between before and after the JACK workshop. (Likert ratings: 1 = Not at all, 2 = A little, 3 = Some, 4 = Quite a bit, 5 = A lot, 6 = Mostly, 7 = Completely).

Figure 3

Score on pre- and post-workshop ocean literacy knowledge survey as predicted by pre-workshop ranking of the importance of oceans. Knowledge gain on areas of ocean literacy was even across all rankings of the importance of oceans.

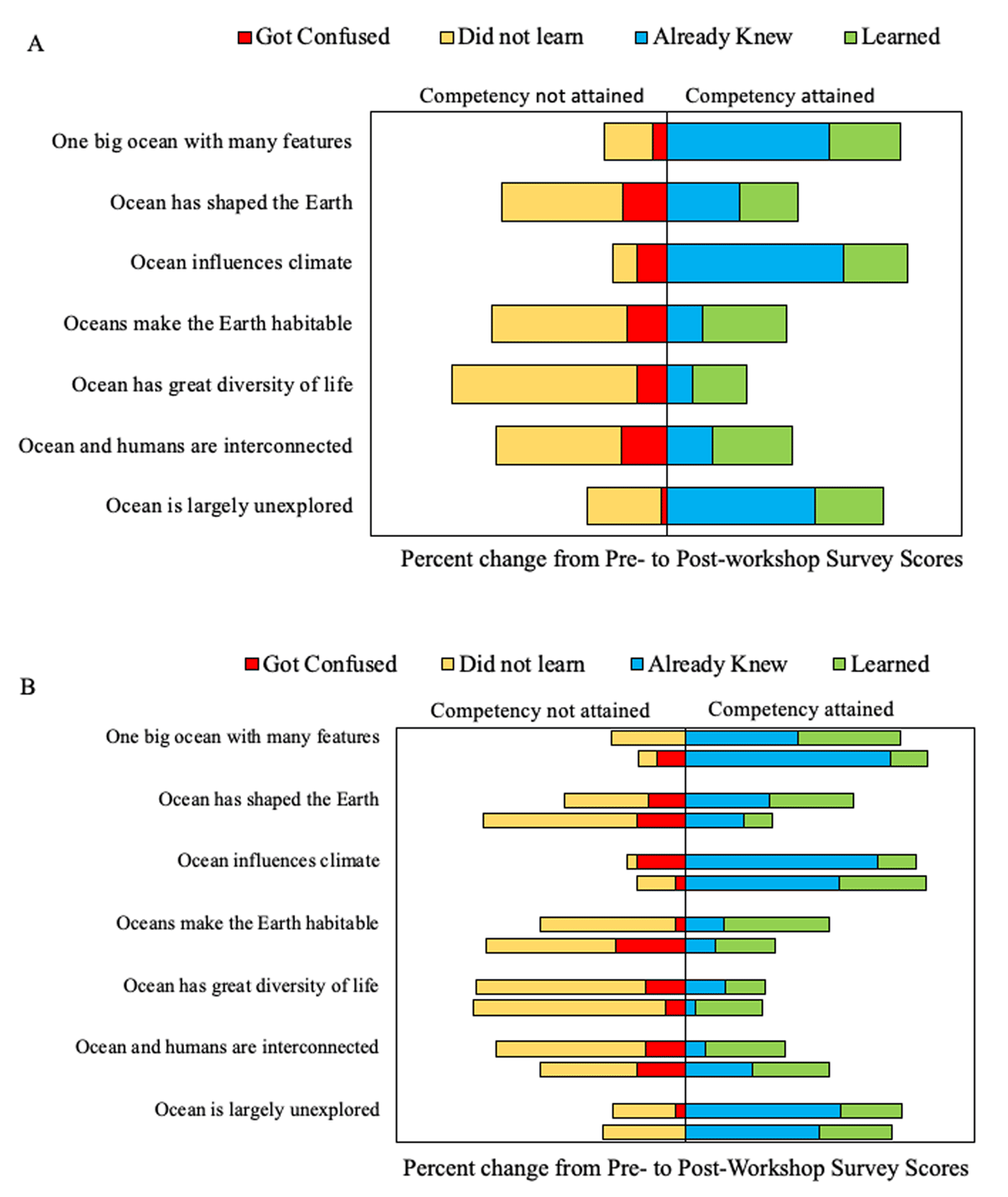

Knowledge-based post-pre scores were organized into four categories: Learned, Already Knew, Did Not Learn, and Got Confused based on pair-wise comparisons within individual participants. Mean pre-workshop answers that were correct on the pre-test and also scored correctly on the post-test (i.e., “already knew”) for all principles combined was 32.1%. There was a mean learning gain of 23.3% in which participants learned one or more principles over the course of the workshop (incorrect response on the pre-test but correct response on the post-test). However, there was a 10.0% rate of “confusion” (answered correctly on the pre-test but incorrectly on the post-test) leaving a net increase of ocean literacy from 32.1% to 45.4% (see Figure 4).

Figure 4

Summary of responses organized by (A) principle of ocean literacy, and (B) by question on the survey (questions 1 through 14). Bars represent percent change from pre- to post-workshop scores on the knowledge survey about ocean literacy. There were two questions per ocean literacy principle that are combined in (A) and parsed in (B).

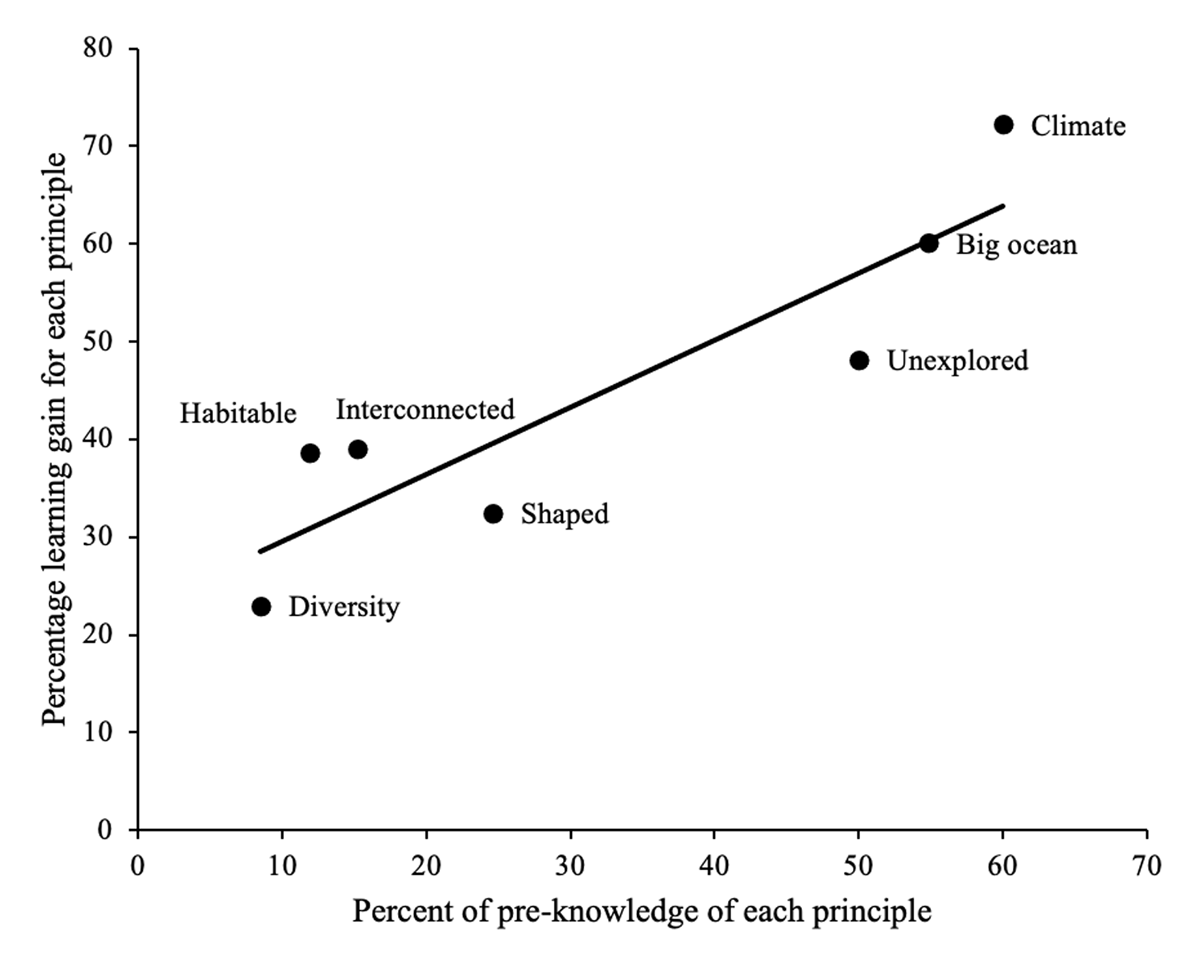

There was a significant difference among the seven principles in the proportion of respondents that already knew the concept (χ2 = 78.20, df = 6, p < 0.001). Pre-knowledge about ocean literacy in our sample population was highest for (1) One big Ocean with Many Features, (2) Ocean Influences Climate and (3) the Ocean is Largely Unexplored. Pre-workshop literacy was low for the role of the oceans in (1) shaping the Earth, (2) making the Earth habitable, (3) the ocean holds great biodiversity and (4) the ocean and humans are interconnected (see Figure 4A). These findings were consistent within pairs of questions assessing each principle of ocean literacy (see Figure 4B). There was also a significant difference among the seven principles in the proportion of participants that did not know the principle before the workshop but had learned it by the end of the workshop (χ2 =16.92, df = 6, p = 0.010; see Figure 4A). These trends were also reflected consistently within pairs of questions for each concept of ocean literacy (see Figure 4B). Individual principles of ocean literacy that showed the highest gains in learning were also the principles that had the highest levels of pre-knowledge (Pearson r = 0.899, p = 0.006, see Figure 5) suggesting that knowledge gain was not determined by the potential for gain but by either inherent difficulty in grasping the principle, or that participants who already knew a concept before the workshop helped facilitate learning by participants who did not know that concept of ocean literacy before the workshop. Three ocean literacy concepts, there is one big ocean, ocean influences climate and the ocean is largely unexplored clustered together as having high levels of pre-knowledge and high levels of learning gain, while the other four principles of ocean literacy scored relatively poorly in both pre-knowledge and learning gains (see Figure 5).

Figure 5

Relationship between level of pre-knowledge for each area of ocean literacy by some participants and learning gain by their classmates.

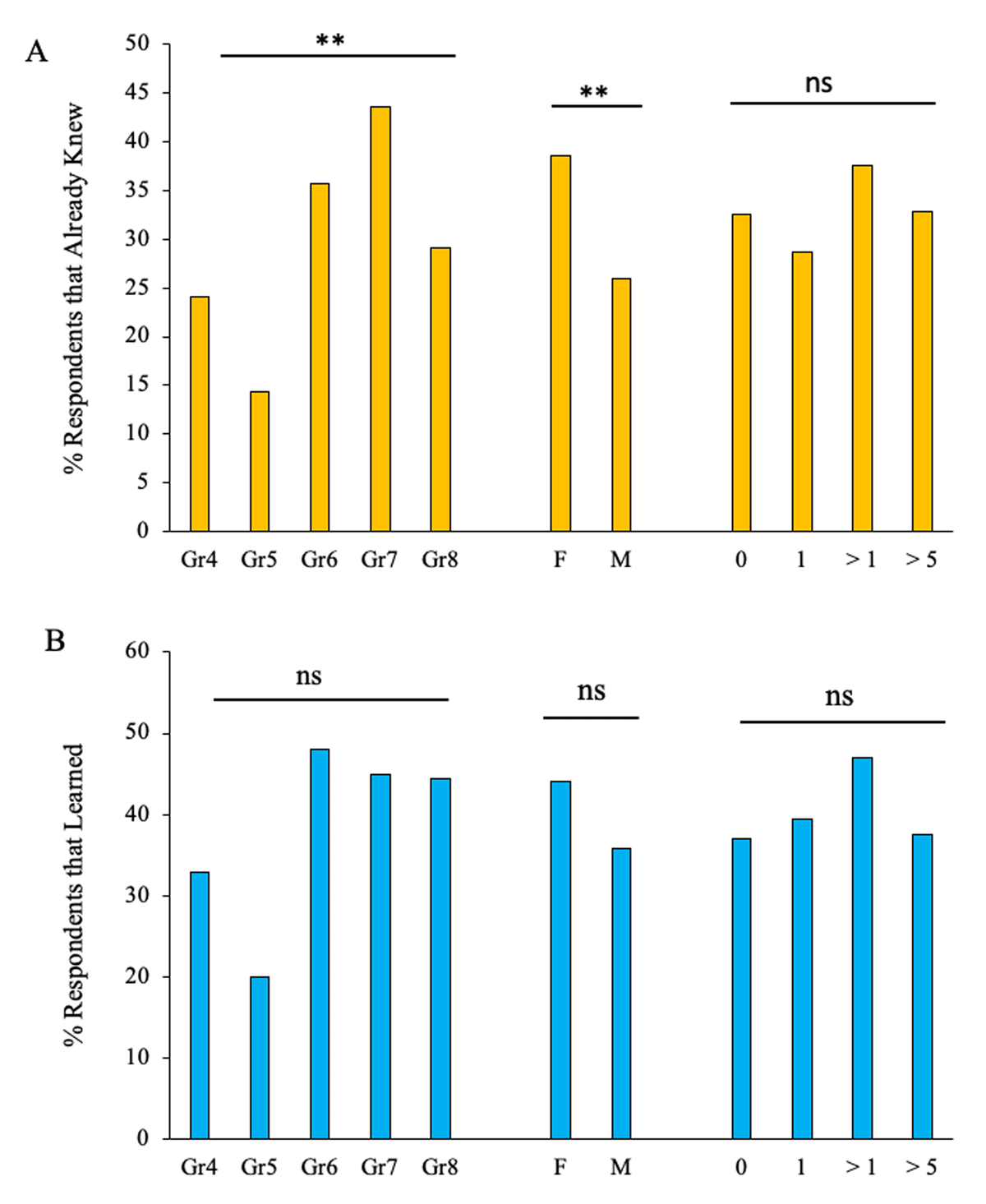

There was a significant effect of grade level (χ2 = 15.68, df = 4, p = 0.003) and sex (χ2 = 7.53, df = 1, p = 0.006) on pre-knowledge of ocean literacy (see Figure 6A) but neither had any effect on learning gains (Age: χ2 = 7.16, df = 5, p = 0.128; Sex: χ2 = 1.68, df = 1, p = 0.195, see Figure 6B). Older participants came into the workshop with greater pre-knowledge than younger participants, and females had more pre-knowledge that males did. Previous experience with oceans, limited as it was, had no effect on pre-workshop ocean literacy (χ2 = 1.87, df = 3, p = 0.600) or on learning gains (χ2 = 1.36, df = 3, p = 0.714; Figure 6). Sample sizes for classification of schooling types were too small to permit statistical comparison.

Figure 6

Percent of respondents with pre-knowledge of the concepts of ocean literacy (A) and those that made learning gains as a result of the workshop experience (B), as a function of grade level, sex, and ocean experience.

Discussion

Experience with oceans among our pool of participants had no effect on pre-knowledge of the ocean literacy principles nor the amount of knowledge gained by the end of the workshop. This is contrast to youth in grades 3 – 6 from Croatia, Italy and Greece that showed greater ocean literacy knowledge if they lived in a coastal city instead of away from the coast, and those that had access to a marine institute or public aquarium similarly achieved higher scores in ocean literacy than students without that benefit (Mogias et al. 2019). In our study, the lack of an effect of experience with oceans may reflect that young people acquire information from a variety of sources including online sources (Mogias et al. 2019), that youth that enrolled in the JACK workshop comprised a biased, non-random small sample of highly motivated young people with a homogeneous level of interest in ocean life, or that the level of ocean experience of even the highest levels of engagement with oceans in our candidate pool (more than 5 visits to the ocean) was still too low to impact pre-workshop ocean literacy scores or motivate learning gains. Nevertheless, in the current study even participants who has never been to the ocean, or who had visited the ocean only once, were able to make significant gains in ocean literacy from the curricula offered at the 2023 JACK workshops.

The concepts of there being one big ocean, that the ocean regulates weather and climate and that the ocean is largely unexplored had both the highest levels of pre-workshop knowledge and knowledge gains. We cannot distinguish between two possible mechanisms to explain this result. One possibility is that the three areas of ocean literacy with the highest pre-knowledge and knowledge gains are intuitively the easiest to grasp by youth aged 9–14 compared to the four areas of ocean literacy that scored poorly (Chang et al. 2021). Alternatively, there may have been significant sharing of information between informed and uninformed participants during the workshop that was independent of the curricula being presented. Peer-to-peer teaching and learning is well known to occur in group settings such as our workshop (Stigmar 2016). Either or both mechanisms may have contributed to the heterogeneous results in this study.

Literacy principles that involve effects acting over vast expanses of geological time were generally more difficult to intuit than the immediate observations that there is one big ocean, that the ocean influences global climate patterns and that the ocean is largely unexplored. The surprising exception in our data was low pre-knowledge scores and low learning gains about organismal and ecosystem diversity that occurs in the ocean. This is a cause for revisiting the JACK activities used to demonstrate this principle of ocean literacy and/or re-wording the questions used to assess this knowledge to be age-appropriate. Education standards prepared to teach principles of ocean literacy recognize a sliding scale of conceptual complexity to match cognitive development in K12 curricula (Schoedinger et al. 2005; Halversen, Schoedinger & Payne et al. 2021).

It is unfortunately difficult to compare pre-workshop ocean literacy knowledge and learning gains during the JACK workshop in our sample population with other assays of ocean because assessment tools vary considerably among studies (Payne et al. 2022). In a study on Croatian youth aged 8–9 years old, mean scores on a knowledge test were 50.81% correct before a series of workshops on concepts relating to ocean literacy, and 56.98% 3 weeks later (Mokos 2020). These values are broadly similar to pre- and post-workshop scores observed in the current study, i.e., 42% and 56% correct on pre- and post-tests, respectively. The ocean literacy principles that showed high pre-knowledge in the study by Mokos et al. (2020) were the ocean impacts people (81% correct), more research on the ocean is needed to help protect the ocean (80% correct) and that fish fossils found in rocks on top of mountains indicate that the ocean shapes the earth (85% correct). In the Croatian sample, 68% answered correctly on the question about the ocean and people being interconnected (Mokos, Realdon & Zubak Čižmek 2020). Clearly, Croatian youth in the study by Mokos, Realdon & Zubak Čižmek (2020) demonstrated greater pre-workshop awareness of the role the ocean plays in the day-to-day lives of people. In the post-workshop sample in the study by Mokos, Realdon & Zubak Čižmek (2020), learning gains were slightly higher for females (7.52%) than for males (7.29%). Mogias et al. (2019) found no effect of sex on pre-knowledge of ocean literacy. In our study we observed higher ocean literacy in females than males in the pre-workshop test but no difference in knowledge gain or overall score in the post-test scores.

The concepts with the greatest learning gains in the sample by Mokos, Realdon & Zubak Čižmek (2020) were related to the principles of the ocean makes the Earth habitable, that the ocean contains great biodiversity, and that the ocean and people are interconnected (Mokos, Realdon & Zubak Čižmek 2020). Interestingly, there was an 11% decline (i.e., “got confused”) in scoring success on the questions relating to how the ocean has shaped the Earth over geological time (Mokos, Realdon & Zubak Čižmek 2020).

Future iterations of JACK workshops will more deliberately target the ocean literacy principles that had low pre-knowledge and low learning gains in the 2023 data set. We will also expand the survey to include qualitative assessment data, which are lacking in the 2023 data set. Specifically, we will develop and assessment tool for measuring intention for behavioral changes to promote ocean health. We will also adapt the curricula from 2023 to short, 1-h sessions for visiting K12 groups, training and collaborating with in-service teachers from area schools, and pre-service education students to aid in this effort. Finally, we will use these findings to inform signage and talking points for working with families and mixed-age groups from the general public that tour the facility because JACK and work with K12 students is aimed at youth, while adults from all backgrounds (Worm et al. 2021) are the ones that ultimately shape environmental policy (Kelly et al. 2021).

Conclusions

Ocean literacy of participants in the Junior Aquarists Camp for Kids was low before the workshop (41.6%) but improved significantly on post-workshop assessment surveys (55.9%). Pre-knowledge and learning gains were highest for three principles of ocean literacy: the role of the ocean in regulating weather and climate (60%), that there is one big ocean with many features (55%) and that the ocean is largely unexplored (50%). Learning gains remained stubbornly low for awareness of the role of the ocean in shaping the Earth (4.9%), making the world habitable (15.3%), that the ocean and humans are inextricably interconnected (11.9%), and the ocean supports a great diversity of habitats and species (8.4%). Future research should consider more effective ways to convey principles of ocean literacy that received low learning gains in this study. Based on the poor Cronbach’s alpha, our question #2 needs to be revised. Additional study could tailor curricula to engage youth of different ages and different levels of cognitive development. These results will inform future revisions to the JACK curricula and be used to guide the development of programming for adults and families that visit the MSUM Oceanarium.

Data Accessibility Statement

Data are available from datadryad.org at this link DOI: 10.5061/dryad.ffbg79d1z

Ethics and consent

All methods, surveys, and parental consent forms were evaluated and approved by the MSUM Institutional Review Board and issued protocol number 2031300-1.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to an anonymous reviewer for constructive suggestions on ways to improve the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.