Background Information

Program Background

This lesson was developed through the Virginia Scientists and Educators Alliance (VA SEA) program, a collaboration between the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) and the Chesapeake Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve in Virginia (CBNERR-VA). VA SEA is a network of marine science graduate students, K-12 teachers, and informal educators. Through this program, graduate students receive training in science communication and lesson plan development, while teachers test, review, and implement lessons rooted in authentic scientific research. By integrating real-world research from scientists, teachers enhance their students’ understanding of the scientific process with engaging and relevant examples of scientific inquiry.

Figure 1

In this lesson plan, students will use ecological information about marine animals to solve a murder mystery, identifying motive, means, and opportunity for each animal suspect.

Topic Background

The deep sea, the largest and least explored ecosystem on Earth, plays a crucial role in global climate regulation and biogeochemical cycles (Ramirez-Llodra et al. 2010). Despite its vastness and ecological significance, this environment remains largely unfamiliar to the public and is often perceived as disconnected from human society (e.g., Darr et al. 2020). However, deep-sea ecosystems, and their inhabitants, provide essential services, including deep-sea carbon storage (sequestration), nutrient cycling, mineral resources, and biodiversity supporting global fisheries (Levin & Le Bris 2015). A particularly important yet underappreciated phenomenon in the deep ocean is diel vertical migration (DVM)—the largest daily movement of biomass on the planet and a behavioral adaptation to living in the deep sea—where large numbers of organisms, including fish, squid, and zooplankton, ascend to the surface ocean at night to feed and return to the deep sea during the daytime to evade predators (Hays 2003) (Figure 2). This massive migration sustains oceanic food webs, connecting the surface ocean and deep sea, and plays a crucial role in nutrient cycling and deep-sea carbon storage (Steinberg & Landry 2017).

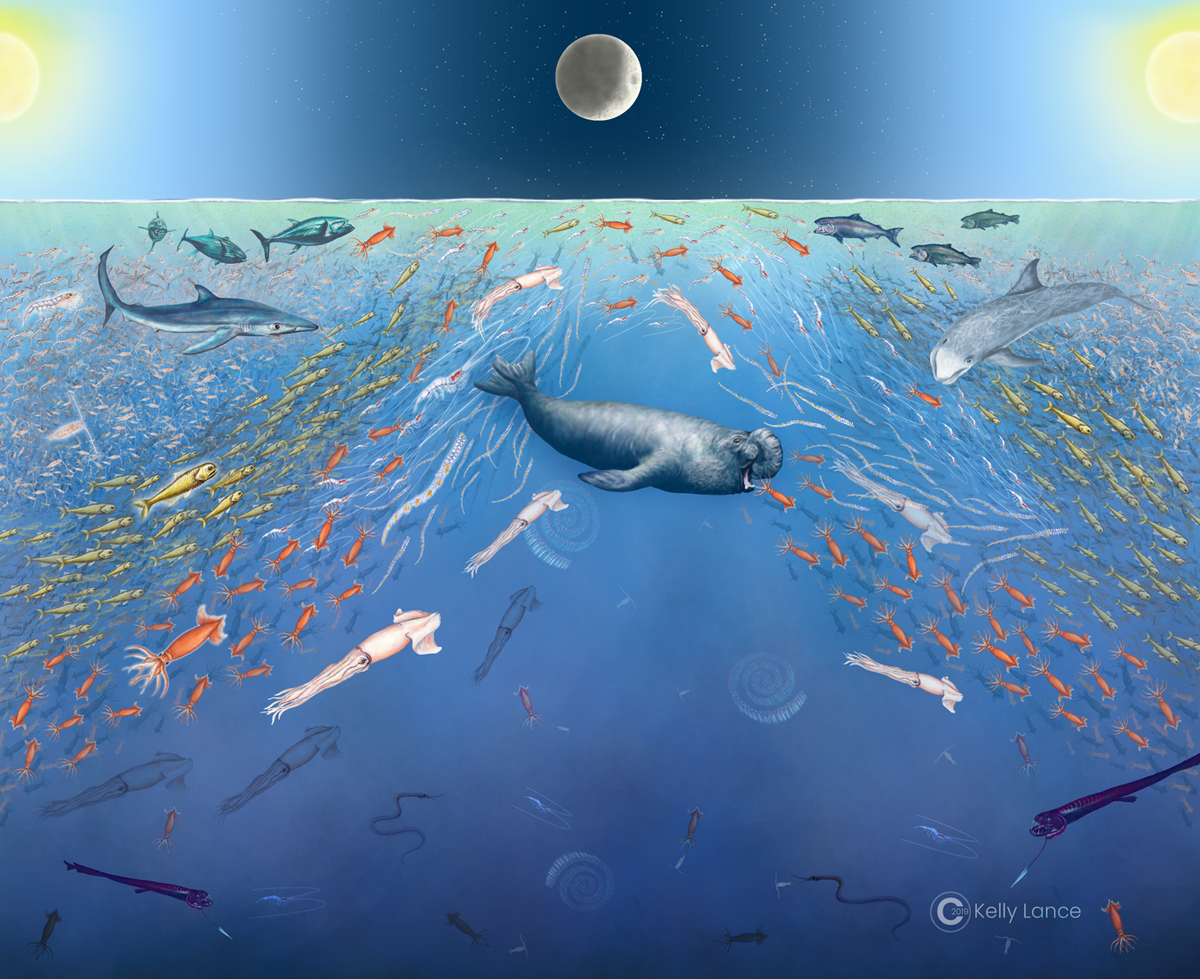

Figure 2

Diel (daily) vertical migration of animals from the Twilight Zone (200–1000 m) to the surface at dusk and descent to depth at dawn. Illustration by Kelly Lance, reprinted with permission.

Sampling the Deep Sea: a MOCNESS Monster!

So, how do we detect this great vertical migration? One method for capturing deep-sea animals is to use a piece of equipment known as a Midwater Opening and Closing Net and Environmental Sensing System (MOCNESS). A MOCNESS is a series of nets (often 10) towed behind a research vessel that open at different depth intervals as the MOCNESS returns to the surface. When one net opens, another closes so that one net is always open to sample a different depth zone of the water column. Comparing the catch from daytime and nighttime tows can reveal which animals migrate to the surface at night.

Figure 3

A Multiple Opening/Closing Net and Environmental Sensing System (MOCNESS) is deployed off the side of the Research Vessel Roger Revelle during a NASA-funded research cruise. Each MOCNESS net samples a different depth zone of the water column; when one net closes, another automatically opens. Photo credit: NASA.

Lesson Plan Overview

To introduce students to the complexity and importance of deep-sea ecosystems, this lesson plan takes an investigative approach by framing the learning experience as a “murder mystery” involving deep-sea species (Figure 1). By integrating real-world examples of scientific data, students develop hypotheses, analyze ecological evidence, and apply critical thinking to solve an open-ocean mystery. This lesson plan aligns with the 5E instructional model (Engage, Explore, Explain, Elaborate, Evaluate), an effective strategy for promoting scientific literacy and inquiry-based learning (Bybee et al. 2006). This lesson is intended for middle and high school students. Corresponding objectives, next-generation science standards, and alignment with ocean literacy principles are provided in Table 1.

Table 1

Relevant standards (Ocean Literacy and Next Generation Science Standards) and lesson objectives.

| Next Generation Science Standards | MS-LS2–2. Construct an explanation that predicts patterns of interactions among organisms across multiple ecosystems. HS-LS2–2. Use mathematical representations to support and revise explanations based on evidence about factors affecting biodiversity and populations in ecosystems of different scales. |

| Ocean Literacy Principles | OLP-5D: Ocean biology provides many unique examples of life cycles, adaptations and important relationships among organisms that do not occur on land. OLP-5E: The ocean provides a vast living space with diverse and unique ecosystems from the surface through the water column and down to, and below, the seafloor. OLP-5H: Density, pressure, and light levels cause vertical zonation patterns in the open ocean. Zonation patterns influence organisms’ distribution and diversity. |

| Science Objectives |

|

| Math Objectives |

|

Instructor Preparation and Materials (Table 2)

Activity A (“Cold, Dark, and under Pressure”): can be completed by students individually or in groups; estimated time: 15–20 mins

Activity B (“Deep-Sea Sampling”): can be completed by students in groups; estimated time: 45–50 mins

If necessary, challenge questions can be completed at home; estimated time: 20–25 mins

Activity C (“Solving the Murder”): can be completed by students in groups; estimated time: 10–15 mins

Table 2

Supplies needed for lesson plan activities.

| DESCRIPTION | NUMBER | ACTIVITY | PURPOSE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assorted markers, including yellow and black/blue | Minimum of two colors per group of students (suggested group size: 2–4 students) | A & B | Activity A: plotting environmental data Activity B: plotting day (yellow) and night (black/blue) abundance values on depth profiles |

| Plastic/Ziplock bags | 6 bags per group of students | B | Activity B: these will represent the “trawl net” containing “captured animals” (see Figure 4b) |

| Permanent marker | 1 | B | Activity B: use this to label and identify the Ziplock bags (e.g., “trawl net sampling the surface zone, 0–200 m” – see Figure 4b) |

| Printed illustrations (see lesson plan flash cards). Alternatively, for an edible version of this activity, use Swedish fish candies | Number of animals can vary at instructor’s discretion, but ratios should be consistent with those provided Table 3. If using Swedish fish candies, a minimum of 5 unique colors/shapes is necessary to represent the 5 different animals in the activity. | B | Activity B: these will represent the “captured animals” within each trawl catch (see Figure 4b) |

Print lesson plan handouts, keeping in mind each student should receive their own copy of the lesson plan, but the activities and discussion questions can be completed in groups (at the instructor’s discretion). Prepare Ziplock bags (representing “MOCNESS nets”) containing printed animal illustrations (or Swedish fish candies; representing “captured animals”) for Activity B (“Deep-Sea Sampling”). The instructor should match the ratios of printed animal illustrations to Table 3. The instructor can slightly change the number of animals in the bags for the different groups of students; however, it is important to ensure that the ratios of abundance in day and night nets are consistent with Table 3 so that students produce consistent vertical distribution profiles (i.e., we want the total number of animals for each species captured during the daytime and nighttime to be the same). For example, the instructor may choose to put 6 (instead of 4) flying fish in the 0–200 m daytime net and 6 flying fish in the 0–200 m nighttime net.

Table 3

Abundance of each organism (represented by printed illustrations or candies) in each MOCNESS net (Ziplock bag). See Figure 4b for example.

| ORGANISM | DAY | NIGHT | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–200 m | 200–1000 m | 1000–4000 m | 0–200 m | 200–1000 m | 1000–4000 m | |

| Flying fish | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Lanternfish | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Hatchetfish | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Fangtooth | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Pelican eel | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

Figure 4

a) Educators at the Mid-Atlantic Marine Education Association (MAMEA) conference in October 2022 try Activity B (“Deep-Sea Sampling”). Photo credit: Mid-Atlantic Marine Education Association Facebook page b) Activity B “nets” (plastic bags) containing “animals” (printed illustrations or candies) c) example vertical distribution plot for a Fanfish.

Engage

Emphasize that deep-sea ecosystems are among the least explored places on Earth and build excitement by inviting students to help solve an open-ocean murder mystery involving several marine animals, including deep-sea species. By positioning students as active participants (scientific detectives) in an unfolding mystery, this lesson aims to sustain engagement and reinforce the importance of scientific exploration and problem-solving.

Depending on students’ familiarity with deep-sea organisms, the teacher may also begin with an open-ended discussion about the deep sea, leveraging it as an opportunity to activate students’ prior knowledge, spark curiosity, and set the stage for deeper inquiry. Students can be asked what they know or think about life in the deep sea, including whether they have seen documentaries or news stories about deep-sea creatures. To document students’ ideas and identify common themes, the instructor may use a Word Cloud or sticky notes, allowing students to collectively brainstorm and identify common themes in their perceptions of the deep sea. The instructor can use the included PowerPoint to introduce the deep-sea environment and the diversity of animals inhabiting deep-sea ecosystems.

Explore

Students will complete three interconnected activities that build upon one another. The first two activities guide students through “evidence” collection (in this case, environmental and biological data analysis and interpretation) that students use in the final activity to solve the murder mystery.

Cold, Dark, and under Pressure: In the first activity, students will graph and analyze data to understand how environmental change creates discrete vertical habitats in the ocean.

Deep-Sea Sampling: Students will collect, graph, and interpret data on the vertical distribution of marine organisms (Figure 3). They will explore how deep-sea animals are specialized for different depth zones and discuss the evolutionary adaptations that help them thrive in their environments.

Solving the Murder: In the final activity, students will identify biological adaptations to life in the deep sea and use various clues—including ecological information from previous activities, “detective notes,” and “suspect profiles”—to unravel the mystery (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Introduction to Activity C (“Solving the Murder”). Students will use information from previous activities, the detective’s notes, and ecological information about each suspect to identify which animal committed the crime.

Explain and Elaborate

After collecting and plotting data in Activities A and B, students will work collaboratively in groups to interpret their results and discuss broader themes. Both activities include guided discussion and challenge questions designed to promote critical thinking and deepen understanding of the lesson’s scientific concepts.

Cold, Dark, and under Pressure prompts students to interpret graphed data and consider how environmental changes create distinct vertical habitats and influence food web dynamics in the water column. Students also discuss how deep-sea organisms might adapt to or respond to these changing conditions.

Deep-Sea Sampling encourages students to synthesize plotted data, design experiments to test the importance of suspected migration cues, and predict how diel vertical migration characteristics (e.g., distance and speed) may differ across ocean regions. Students also reflect on how climate change could impact these migration behaviors.

These discussions support students in thinking like scientists by encouraging them to ask questions, make predictions, and draw evidence-based conclusions. Supplemental articles and additional resources are included in the lesson plan to help students answer questions and connect their ideas to broader scientific themes.

Full worksheets and materials can be accessed here.

Evaluate

Instructors can assess student learning and performance using a variety of tools embedded within the lesson:

The graph templates from Activities A and B provide a structured way to evaluate students’ ability to collect, organize, and interpret data. By analyzing students’ graphs, instructors can gauge their understanding of how environmental factors shape vertical ocean habitats and influence the distribution of marine organisms.

The discussion and challenge questions in Activities A and B serve as another key evaluation tool, allowing instructors to assess students’ critical thinking skills, comprehension of key scientific concepts, and ability to apply knowledge to new contexts. In group discussions, instructors can listen for students’ ability to explain concepts, support their reasoning with evidence, and draw connections between deep-sea adaptations and broader scientific principles. The challenge questions in Activity B encourage higher-order thinking by prompting students to formulate testable hypotheses and link their learning to other scientific phenomena such as circadian rhythms and climate change.

Activity C provides a final layer of assessment by having students collate and synthesize information from previous activities into the table of suspect information, applying their understanding of deep-sea ecosystems to solve the murder.

Beyond these formal assessments, the lesson also fosters opportunities for meaningful discussions about larger scientific issues. For example, instructors can facilitate conversations about how climate change will impact oceanic animals or the marine carbon cycle.

Conclusion and Lessons Learned

This lesson uses a narrative-based inquiry approach to engage students in exploring deep-sea ecosystems, diel vertical migration, and adaptations to life in the deep ocean. Classroom pilots revealed several lessons learned and potential challenges. Some students struggle with interpreting environmental data and graphing vertical patterns; modeling an example at the start of Activity A can help to guide these students. Because Activities B and C are designed to be cumulative rather than modular, adapting the timing can be difficult in shorter class periods. Instructors are encouraged to preview the lesson in advance and consider assigning discussion questions or graphing exercises as homework to maintain pacing. Additionally, some students benefit from extra guidance in linking organismal adaptations to environmental gradients, which can be reinforced through guided discussion and use of the accompanying introductory PowerPoint. Despite these considerations, the “mystery” framing has proven highly effective in sustaining engagement and encouraging participation across a wide range of learners. With appropriate scaffolding, the lesson provides not only content knowledge but also opportunities for students to practice scientific reasoning, helping them build a deeper and more authentic understanding of how ecological interactions structure and sustain deep-sea ecosystems.

About VA SEA

Tor Mowatt-Larssen a Ph.D. student in the Coastal and Ocean Processes Section at the Batten School of Coastal & Marine Sciences and Virginia Institute of Marine Science, created this lesson. The lesson encourages students to explore the deep-sea environment and biological adaptations to living in the deep sea through graphing activities and a murder-mystery investigation. This lesson plan was developed through the VA SEA program, a collaborative network of graduate students, teachers, and informal educators committed to transforming scientific research into engaging, classroom-ready lesson plans (Figure 6). Established in 2015 by educators from the Chesapeake Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve in Virginia (CBNERR-VA) and the VIMS Marine Advisory Program, VA SEA serves two primary objectives: (1) to train graduate students in effectively communicating their research to a broader audience, and (2) to enhance K-12 students’ research skills by integrating authentic scientific research into the classroom. Since its inception, VA SEA has supported 76 graduate students from universities in Virginia, Florida, and New Jersey in developing 87 research-based lesson plans. These lessons undergo a collaborative refinement process, where classroom teachers pilot them with students and provide feedback to lesson plan authors to ensure that lesson plans are scientifically rigorous and pedagogically effective. A teacher reviewer shared this feedback on the lesson plan “The activities were much like doing an interactive lab with students. Students were able to connect the concept of animal adaptations clearly in my class. The content was strong and really creative.” All VA SEA lesson plans connect science to issues in the public sphere and allow students to investigate scientific phenomena with real-world data and scenarios.

Figure 6

The Virginia Scientists and Educators Alliance (VA SEA) logo.

To access the full lesson plan, including student worksheets, answer keys, associated PowerPoint, please visit – Video Summary, Lesson Plan (PDF), Student Handouts, and PowerPoint.

To access the entire VA SEA lesson plan collection, visit www.vims.edu/vasea.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.