1. Introduction

1.1 Background and motivation

The architecture, engineering and construction (AEC) industry plays a critical role in the climate crisis, accounting for a substantial proportion of CO2 emissions (UNEP & GlobalABC 2022). These emissions stem not only from the energy consumed during the operation of buildings but also from embodied carbon (IEA & GlobalABC 2019). As operational emissions decline through improvements in energy efficiency and grid decarbonisation, embodied emissions represent an increasingly significant share of total life-cycle emissions (Röck et al. 2023).

In this paper, the terms ‘embodied carbon’ and ‘carbon budgets’ are used as shorthand for embodied greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and GHG budgets, encompassing both CO2 and non-CO2 emissions. All values are expressed as CO2e following ISO 14067 (ISO 2018) and Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2021–23) AR6 conventions.

Recent international research (Crosbie & Baker 2018; Ürge-Vorsatz et al. 2020) suggests that in order to remain within a 1.5°C global warming limit, the building sector must halve its GHG emissions roughly every seven years, which is consistent with the 7%/yr (halving about every 10 years) global ‘carbon law’ and the 5%/yr (halving about every 13 years) upper-bound feasible reduction rates identified in the literature (Rockström et al. 2017; Stocker et al. 2013; Williges et al. 2022). Such trajectories demand absolute, science-based targets that can be applied consistently across the construction sector at the project level. Yet, while national and sectoral carbon budgets have been defined, architects still often lack easy-to-use methods that allow them to test whether individual projects align with these pathways.

Several studies have explored how carbon budgets could be allocated at national and building scales. Kropp et al. (2022) examine the GHG budget for the German building sector in relation to the 1.5°C target, providing policy-oriented insights. Habert et al. (2020) discuss temporal and spatial allocation of carbon budgets at the building level, offering conceptual guidance for framework design. Perissi & Jones (2023) propose methods for downscaling European Union (EU)-level carbon budgets to member states, highlighting the potential for allocation-based approaches at national and sectoral scales. Building on these approaches, Horup et al. (2023) define dynamic, science-based climate change budgets for countries and translate them into absolute sustainable building targets, providing a methodological bridge between national pathways and project-level implementation.

Despite these advances, the methodological connection between science-based carbon targets and their operationalisation in design practice remains limited. Whereas Habert et al. (2020) harmonise cross-scale carbon-budget definitions conceptually, the presented method translates 1.5°C pathways into project-ready, usage-specific budgets for early design decisions and mixed-use allocation. This method defines function-specific, project-level GHG budgets and is based on established and aligned decarbonisation pathways, specifically the Carbon Risk Real Estate Monitor (CRREM) for operational emissions and the Science-Based Targets initiative (SBTi) for embodied emissions. The goal is to bridge the distance between scientific modelling and design practice, enabling professionals to evaluate whether a proposed building contributes proportionally to the sector’s decarbonisation effort.

1.2 Policy context

In response to the climate emergency, the EU has set a binding target to achieve climate neutrality by 2050 (European Parliament & Council of the European Union 2021). Germany has committed to an even more ambitious goal, aiming to reach net zero GHG emissions by 2045 (Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action 2021/2024). These commitments make the construction sector critical for achieving Europe’s climate action strategy, demanding both significant regulatory innovation and design adaptation. The building sector currently accounts for around 37% of global energy- and process-related CO2 emissions (UNEP 2022), underscoring the urgency of implementing measurable, enforceable reduction targets. The AEC industry must therefore evolve to integrate carbon considerations into early design stages and throughout the building life-cycle, ensuring that architectural practice contributes meaningfully to the 1.5°C global warming limit. Frameworks and methods are urgently needed so they can provide guidance to practitioners as to whether their projects are 1.5°C compatible. Similar to Priore et al. (2021), who demand a 1.5°C target for the Swiss construction sector, there is also no existing framework for Germany and Europe that provides usage-specific, 1.5°C-aligned whole-life-cycle GHG budgets that are readily applicable in the design phase.

The European Commission has outlined a roadmap for decarbonising the building sector. This includes the implementation of project-level carbon limits starting in 2028, which are set to become legally binding by 2030 (Council of the European Union & European Parliament 2024). Several EU member states have already taken steps to introduce embodied carbon caps into their national legislation. Denmark (Ministry of Transport, Building and Housing 2018), France (Ministère de la Transition écologique 2020) and the Netherlands (Ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninkrijksrelaties 2024), for example, have implemented or are piloting embodied carbon limits for new construction. These policy developments indicate a clear trajectory: building projects will soon be required to demonstrate carbon compliance through comprehensive life-cycle assessments (LCAs). Other countries such as Finland and Sweden are expected to follow suit, adopting whole-life carbon-reporting frameworks within the next regulatory cycle. These developments collectively indicate that absolute, life-cycle-based GHG budgets will soon become a standard requirement across Europe. Architects therefore need accessible methods for translating high-level policy objectives into quantitative project targets. The framework presented in this paper responds to that need, offering a science-based and practice-oriented approach for integrating 1.5°C-aligned budgets.

1.3 Life-cycle assessment in architecture

Despite whole-building life-cycle assessment (WBLCA) being an established method for decades, architectural practices are increasingly incorporating it into design workflows (Prideaux et al. 2024). Traditionally, environmental assessments have focused on operational energy use and thermal performance. However, as operational emissions decline, attention is shifting towards embodied impacts, those associated with materials extraction, manufacturing, transport, construction, maintenance and end-of-life (Pomponi & Moncaster 2016). LCA provides the methodological foundation for quantifying these impacts consistently across the entire life-cycle of a building, following standards such as EN 15978 (CEN 2012) and ISO 14067 (ISO 2018).

The proposed framework builds on this foundation, using LCA as the basis for linking design decisions to 1.5°C-aligned emission trajectories.

1.4 Limitations in existing practice

Despite the increasing use of WBLCA, most applications remain comparative rather than prescriptive. Designers can identify that option A has a lower carbon footprint than option B, yet such relative assessments fail to answer the essential question: is this option (i.e. a proposed building design and specification) compatible with planetary limits?

Certification systems such as the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Nachhaltiges Bauen (DGNB), Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method (BREEAM) and Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) incentivise incremental improvements but do not define their alignment with a 1.5°C trajectory.

Several initiatives have moved the conversation from ‘lower is better’ to ‘how low is low enough’. The Royal Institute of British Architects’ (RIBA) (n.d.) 2030 Climate Challenge was the first professional charter to publish absolute kg CO2e/m2 targets for UK offices, schools and housing, updated annually to track grid decarbonisation. Architecture 2030 (2025) widened the lens to North America, issuing incremental percentage-reduction schedules that culminate in net zero operational and embodied emissions by 2030, but still express intensity relative to a 2003 baseline rather than a fixed carbon budget. The International Energy Agency’s Energy in Buildings and Communities Programme (IEA-EBC) Annex 72 (Passer et al. 2023) delivered a harmonised life-cycle calculation framework and a large empirical database of embodied-GHG intensities, while the ongoing Annex 89 (Passer 2023–27) is developing guidelines for establishing whole-life carbon targets, establishing Paris Agreement-compatible assessment frameworks and mapping tools to support the transition to net zero whole-life carbon buildings.

This gap motivated the development of the proposed framework capable of establishing absolute, project-level carbon budgets aligned with the 1.5°C pathway, usable from the earliest design stages and tailored to the European building context. The contribution is procedural: the CRREM and SBTi pathways are translated into an early-design, project-level calculator tailored for European practitioners. In addition, a set of usage categories is derived from both the authors’ professional experience and the typologies defined in CRREM and DGNB, in order to better reflect the complexity of real-world projects. The resulting targets are specific to each country and to the projected year of completion.

2. Methodology

2.1 Requirements

To translate science-based targets into an actionable design parameter, the framework must meet the following requirements:

Project-specific targets

Derive absolute CO2e budgets at the scale of individual projects, rather than using sectoral averages.

Ease of use

Be applicable at the outset of design, before detailed geometry or materials are defined.

1.5°C alignment

Base all calculations on emission pathways consistent with the Paris Agreement.

Geographical specificity

Reflect local energy mixes, construction standards and carbon factors. The initial focus for this study is on European countries.

Time dependency

Account for changing grid intensities and material decarbonisation toward the project’s completion year.

Typological differentiation

Adjust targets for the distinct energy and material intensities of building uses.

Mixed-use applicability

Provide a transparent method for combining multiple use types within one project when needed.

2.2 Review of existing frameworks

A review of major carbon-budgeting frameworks revealed that none currently meets all the above criteria (see Appendix A in the supplemental data online). While most initiatives provide valuable reference points or sectoral benchmarks, they fall short in providing project-level and temporally adaptive targets that practitioners can apply during early design.

The framework presented in this study addresses these deficiencies by operationalising science-based targets at the level of architectural practice, translating sectoral carbon budgets into project-specific limits that can guide design decisions from the outset.

2.3 Foundational frameworks: CRREM and SBTi

The Carbon Risk Real Estate Monitor (CRREM) and the Science-Based Targets initiative (SBTi) emerged from the authors’ analysis as the most robust frameworks aligned with present requirements. CRREM provides detailed, asset-level decarbonisation trajectories based on location, building type and energy performance. It identifies the point at which a building becomes ‘stranded’, or misaligned with climate goals, and is therefore exposed to regulatory and market risks (CRREM Project 2025).

SBTi operates primarily at the corporate level, but provides embodied-carbon benchmarks consistent with global temperature targets. Its Buildings Sector Guidance (SBTi 2025) complements CRREM by addressing materials-related emissions (A1–A5, B4 and C1–C4).

Together, CRREM and SBTi offer country-specific guidance and both recognise the need for usage-specific GHG budgets.

2.4 Functional considerations

This project originates from internal research and development efforts within a large German architectural practice. The practice’s portfolio spans a wide range of building types, including offices, research laboratories, hospitals and industrial facilities. It is argued here that real-word diversity necessitates a usage-sensitive framework: a logistics hall will have vastly different embodied and operational GHG characteristics compared with a life sciences laboratory, even though both need to decarbonise. Furthermore, projects frequently comprise multiple usages. A simple per m2 carbon budget can yield misleading results in some cases. For example, the inclusion of an underground parking garage can make an office building appear more carbon efficient, even though it drives up total emissions due to additional construction requirements (embodied carbon) and the promotion of car use. The presented methodology assigns separate carbon budgets to each usage within a mixed-use building, ensuring appropriate allocation and alignment with climate goals.

The framework classifies projects into eight core usage categories that reflect the diversity of real-world projects: residential, office, retail, parking and logistics, industry, science, health, and culture, as described in Table 1.

Table 1

Definitions of the building typologies considered in this study.

| USAGE CATEGORY | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| Residential | Multistorey residential buildings |

| Office | Multistorey office buildings |

| Retail | Commercial buildings dedicated to selling goods and services directly to consumers; may include high street shops, shopping centres, lifestyle centres and strip malls (enclosed or open air) |

| Parking and logistics | Unheated or only partially climatised structures for storing vehicles (parking) or goods (logistics) |

| Industry | Climatised logistics halls used for industrial purposes |

| Science | Laboratories and research facilities, including specialised production buildings with high structural and climatisation needs |

| Health | Hospitals, clinics and other specialised healthcare facilities |

| Culture | Museums, theatres, libraries and similar cultural venues with significant structural and climatisation requirements |

2.4.1 Operational carbon budget

Operational carbon refers to Module B6.1 (Energy use for heating, cooling, lighting) in the draft DIN EN 15978 revision (CEN 2012); user-dependent sub-modules B6.2 and B6.3 are excluded for comparability. The operational carbon budget for the eight core usages was determined using the CRREM framework. These values represent the cumulative operational emissions over a 50-year period, including energy-related emissions and integrates refrigerant-related F-gases into operational emission factors. For example, the value given for 2030 corresponds to the cumulative operational emissions from 2030 to 2079. For years beyond 2050, the 2050 value is retained, reflecting CRREM data boundaries.

2.4.2 Embodied carbon budget

Embodied carbon refers to Modules A1–A5, B4 and C1–C4 according to EN 15978, covering emissions from materials production (A1–A3), transport to site (A4), construction and installation (A5), replacement (B4) and end-of-life (C1–C4) (CEN 2012).

Budgets are based on SBTi benchmarks where available and supplemented with DGNB-adjusted multipliers for uses not directly addressed by SBTi (Table 2). These multipliers are defined in the DGNB System (DGNB 2023: Criterion ENV 1.1, Appendix). According to the Qualitätssiegel Nachhaltiges Gebäude (QNG) (2024: Section 2.1.1, Rules for determining the requirement value for non-residential buildings, version 14 April 2023), the same DGNB reference classes are applied when establishing the required life-cycle global warming potential limit for QNG certification.

Table 2

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Nachhaltiges Bauen (DGNB)-embodied CO2e reference values.

| BUILDING CLASS | DESCRIPTION | ANNUAL (kg CO2e/m2/yr) | 50-YEAR TOTAL (kg CO2e/m2) | PERCENTAGE DIFFERENCE RELATIVE TO CLASS 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 | Administrative buildings, schools | 12.0 | 600 | ±0% |

| Class 2 | Laboratory buildings, event buildings | 12.5 | 625 | –4% |

| Class 3 | Hospitals | 13.5 | 675 | –13% |

| Class 4 | Enclosed storage rooms, production facilities | 9.0 | 450 | 25% |

| Class 5 | Sports halls | 10.5 | 525 | 13% |

[i] Note: DGNB-adjusted multipliers: embodied CO2e reference values by building class, shown as annual and total emissions over a 50-year period. Differences are relative to Class 1 (Administrative buildings, schools) as the baseline.

Although this approach has limitations, it aligns with the logic of SBTi’s embodied carbon guidance, particularly the grandfathering principle (Le Den et al. 2023), which allocates budgets in proportion to current or historical emissions, recognising that some building types inherently have higher baselines due to usage or technical requirements. Although the grandfathering principle cannot be justified on ethical or distributive grounds for allocation (summarised in Appendix B in the supplemental data online), since it perpetuates historical emission disparities, the method follows its use as established in the SBTi Building Guidance to maintain methodological alignment, data comparability and practical feasibility. The DGNB and SBTi appear empirically well-aligned: their embodied carbon values for office buildings differ by only 1 kg CO2e/m2 (DGNB n.d.; SBTi 2025). All embodied carbon is conservatively allocated to the year of completion.

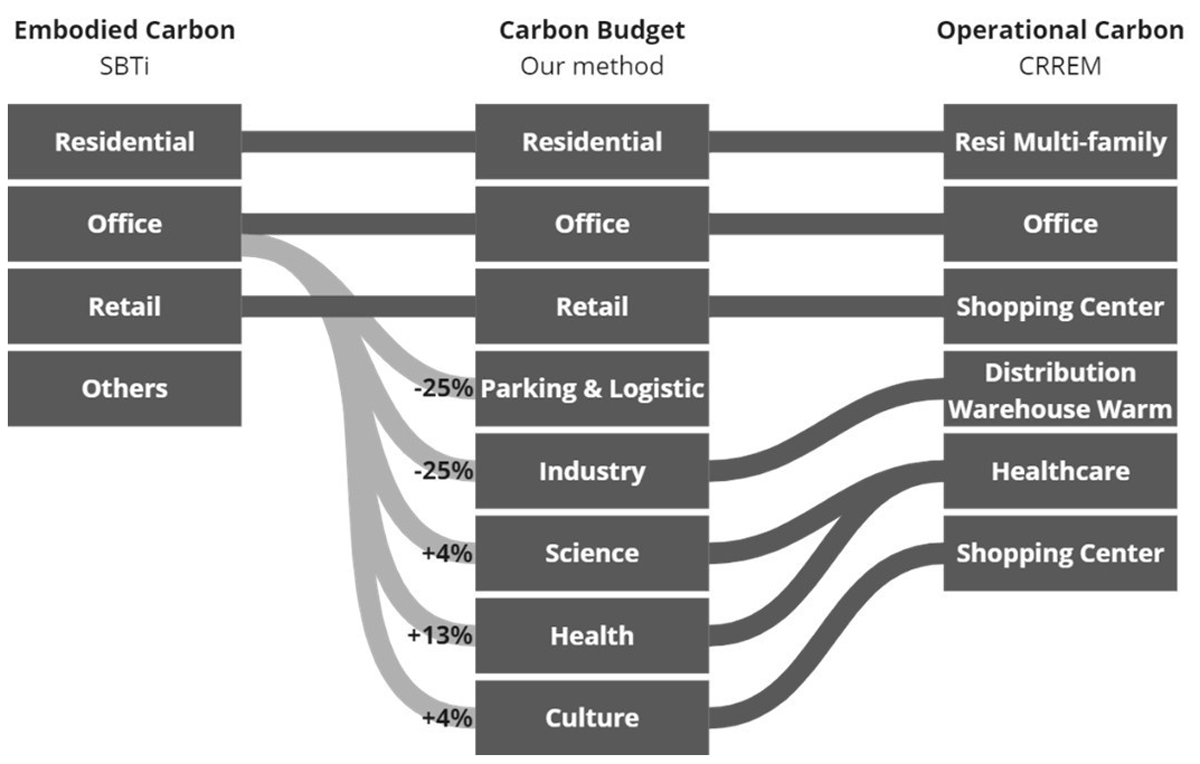

Figure 1 shows the exact derivation of benchmarks from SBTi and CRREM for each building use.

Figure 1

Derivation of the building uses definitions based on the Science-Based Targets initiative (SBTi) and Carbon Risk Real Estate Monitor (CRREM).

Note: Light grey indicates that the SBTi values have been modified based on the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Nachhaltiges Bauen (DGNB)-derived multipliers. The percentage variation is shown next to the respective uses.

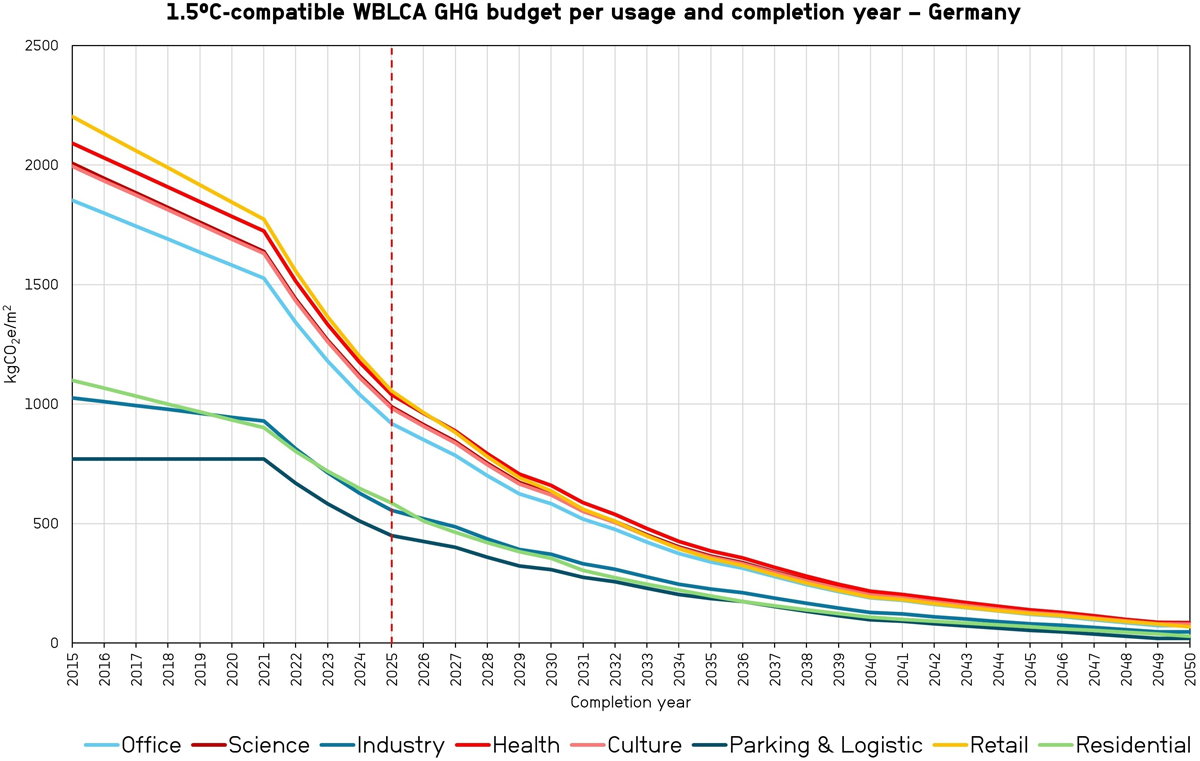

Applying the above methodology with country-specific inputs from CRREM and SBTi, the method derives decarbonisation pathways for eight building-use types across 30 European countries. Figure 2 shows the results for Germany; full datasets are available in the Appendix C and the spreadsheet in the supplemental data online.

Figure 2

Greenhouse gas (GHG)-reduction pathways per m2 for each building use for Germany.

Taken together, the embodied and operational GHG values for any given year (e.g. 2030) represent the full 50-year whole life-cycle GHG emissions of a building completed in that year and assigned a specific usage type. These cumulative values enable practitioners to assess whether a proposed building, when assessed from the moment of completion through its entire service life, aligns with the climate targets consistent with limiting global warming to 1.5°C.

For many building projects, the project timeframe from initial assignment to practical completion often spans around five years. This means that each new project is already operating within a carbon budget nearly half that of a comparable project just one cycle earlier, reinforcing the urgency to act decisively and reduce emissions from the very beginning of the design process.

Once the curves defining the allowable GHG budget per use and completion year are established, the only remaining step is to determine the relative contribution of each use in the project at completion. The total carbon budget for a project is computed using a weighted average based on the net floor area (NFA) of each usage category:

where Ai is the net floor area of usage category i, and Ti is the corresponding GHG target for the completion year.

This enables appropriate carbon allocation across mixed-use buildings.

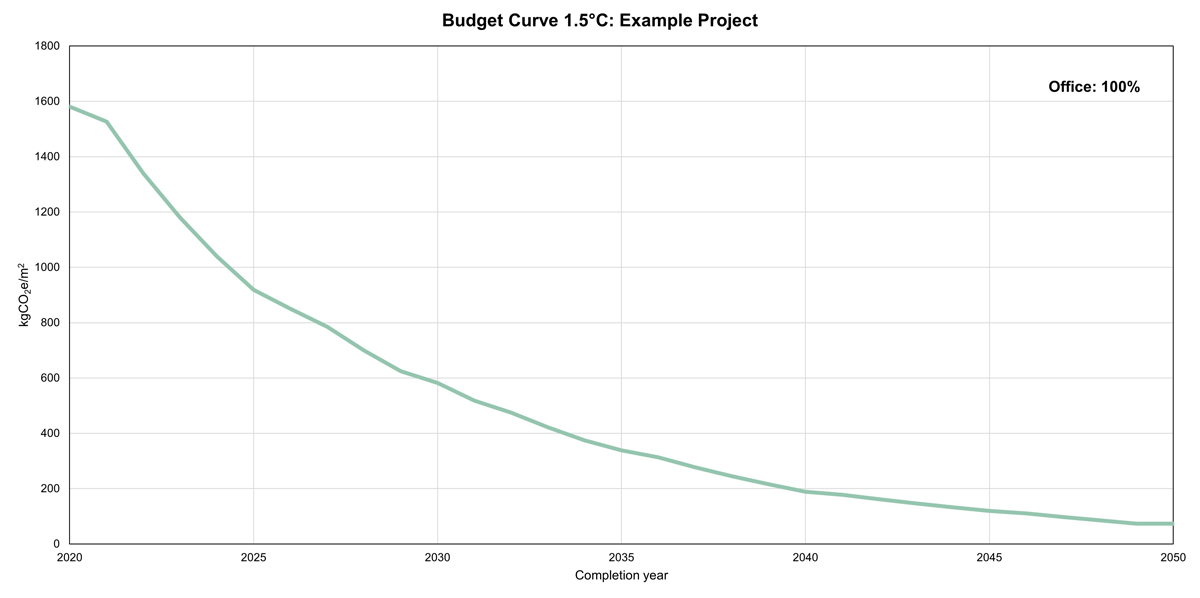

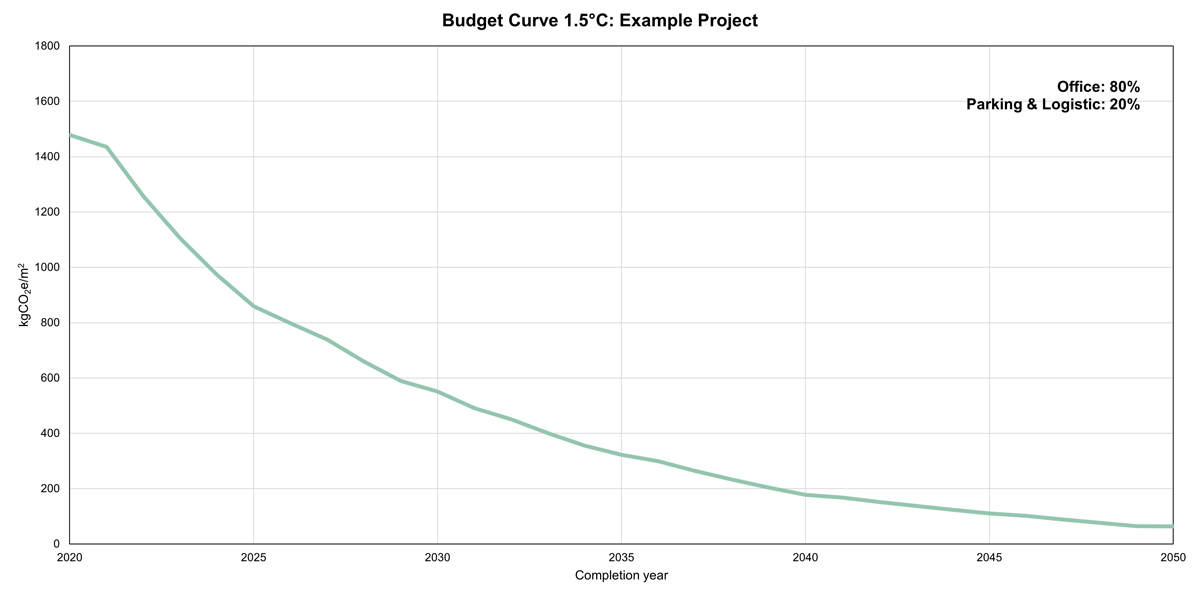

3. Implementation and examples of a mixed-use project

Consider a hypothetical mixed-use project completed in 2025 consisting of 20,000 m2 of office space and 5000 m2 of parking. The framework calculates usage-specific carbon budgets and generates an overall target using the area-weighted formula described above. This allows the target to conform to the specific uses of the building and enables architects to allocate the target’s compliance with climate goals before developing detailed designs (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3

Single-use scenario: the curve shows the reduction in the carbon budget for an office building of 25,000 m2 net floor area (NFA) for Germany.

Figure 4

Mixed-use scenario: the curve shows the reduction in the carbon budget for an office building (20,000 m2 net floor area—NFA) with associated parking (5000 m2 NFA) for Germany.

4. Discussion

Analysis of the framework’s trajectories reveals that total carbon budgets must halve on average every 7.43 years. This rate varies by building usage category, retail and residential buildings reduce faster, while industrial and parking/logistics buildings follow slower trajectories (Table 3).

Table 3

Estimated periods for halving carbon intensity by usage category, based on an analysis of the decarbonisation pathways from 2025 to 2050.

| BUILDING USE | HALVING PERIOD (YEARS) |

|---|---|

| Office | 7.15 |

| Science | 7.03 |

| Industry | 8.30 |

| Health | 7.14 |

| Culture | 7.05 |

| Parking and logistic | 9.72 |

| Retail | 6.37 |

| Residential | 6.65 |

| Average | 7.43 |

[i] Note: The period for halving represents the years required for the embodied carbon intensity to reduce by 50% within each usage category. Shorter halving periods indicate faster rates of decarbonisation.

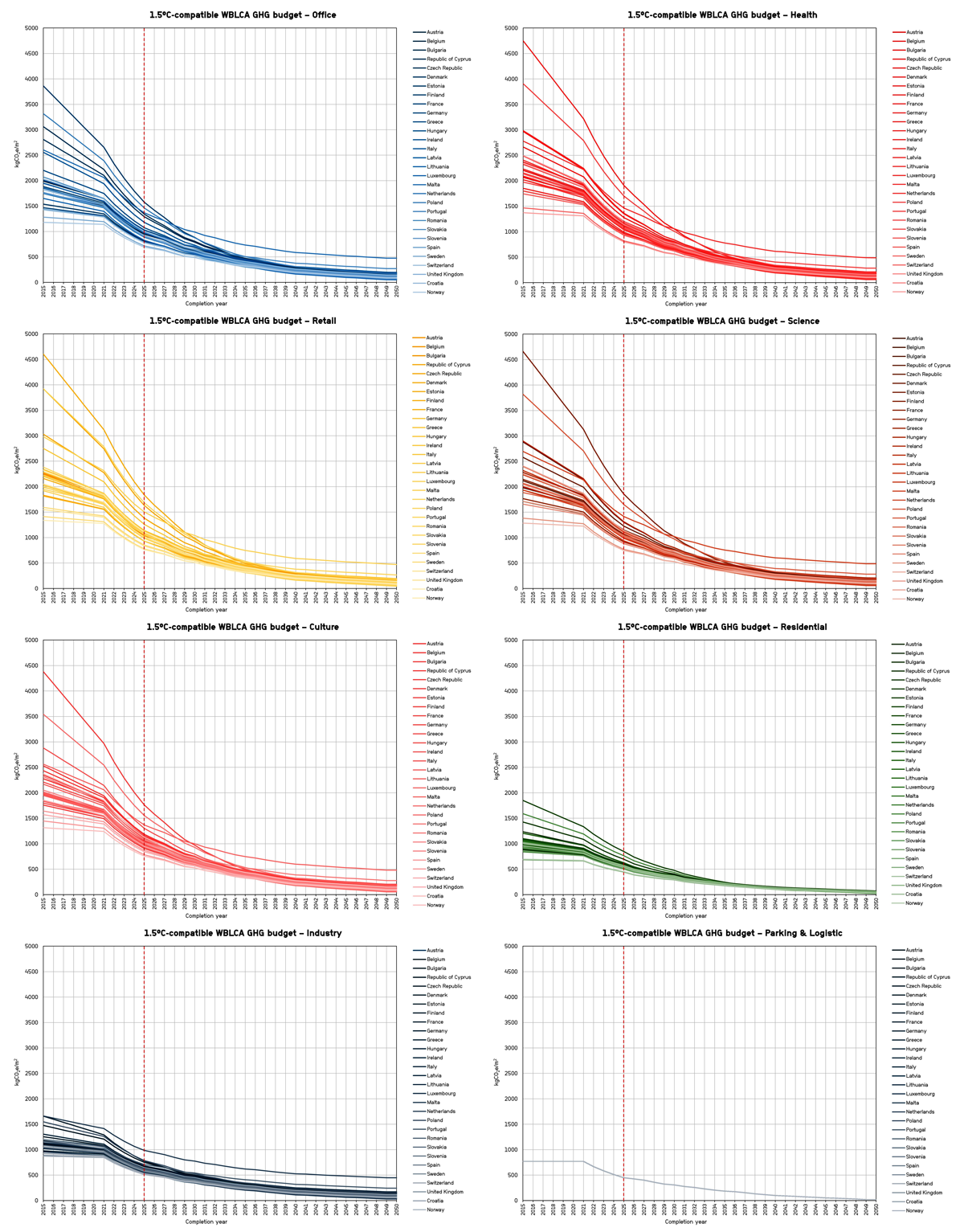

Figure 5 presents the calculated carbon limits per year of completion and per usage category across the 30 European countries considered in this study.

Figure 5

Calculated carbon limits per completion year and usage category across 30 European countries.

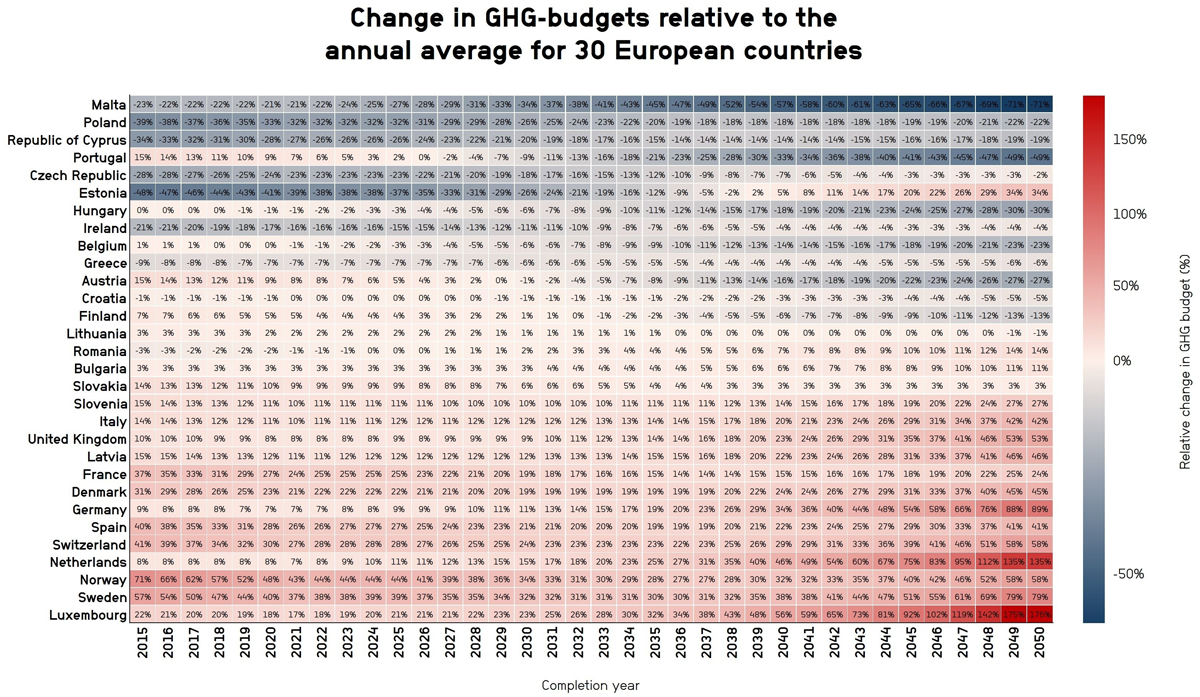

Figure 6 illustrates the relative variation in national GHG intensity trajectories for the usage category ‘office’, benchmarked against the average scenario. As shown, the rate and magnitude of decarbonisation required differ markedly between countries, reflecting heterogeneous starting points and sectoral emission profiles.

Figure 6

Relative variation in annual national greenhouse gas (GHG) intensity trajectories for the office usage category compared with the average scenario.

All underlying data, including country-specific trajectories and usage-based budgets, are publicly available in the accompanying Carbon Budget Calculator (see the Excel spreadsheet) in the supplemental data online.

For a comparison with international standards, specifically the French and Danish carbon limits, see Appendix C in the supplemental data online. Likewise, Appendix D (also online) presents a review of 20 WBLCA from recently completed or ongoing projects at HENN Architects in Germany, evaluating their alignment with the proposed carbon budgets.

4.1 Technical considerations of the calculation protocol

The framework’s structure is shaped by a series of methodological choices aimed at balancing practicality, accuracy and alignment with industry standards. Both CRREM and SBTi assume linear decarbonisation trajectories; however, real-world implementation is often non-linear, suggesting future refinements should include lag-or overshoot effects. One of the core decisions is the use of NFA, based on the definition provided in DIN 277 (DIN 2016). NFA captures the usable internal floor space, excluding structural components, and includes areas intended for use, technical services and circulation. It is a widely used standard in German architecture and planning practice, and while it is not identical to the IPMS2 (IPMS Coalition 2018) standard referenced by SBTi (2025), it is closely aligned in scope and intent.

Another foundational element of the protocol is its adoption of a 50-year assessment period for carbon emissions, starting from the year of a building’s completion. This time frame aligns with the LCA methodology outlined in EN 15978 (CEN 2012) and in certification standards such as DGNB (2023) and QNG (2021). As such, it reflects the typical practice in LCA in Europe.

4.2 Limitations

The framework presented here is intentionally lean and oriented toward early design stages, yet several constraints limit its current scope.

First, the typological range remains narrow. Single-family houses, schools and kindergartens fall outside the present envelope; the tool therefore primarily serves teams working on medium to large-scale commercial or mixed-use projects. Expanding the taxonomy to include these underrepresented building types is a clear next step.

Second, the embodied carbon benchmark provided by SBTi currently consists of a single global value. This benchmark is adapted by the present authors for the European context, but its application beyond Europe would be unreliable and potentially inequitable. The global benchmark reflects Western (European) construction standards and does not adequately account for variations in building practices even within Europe. Moreover, its grandfathering logic could impose disproportionately stringent targets on some non-European regions. More broadly, embodied carbon benchmarks remain based on global averages and fail to capture regional differences in material sourcing, construction methods and supply chains. Incorporating localised data in future iterations would enhance both accuracy and policy relevance.

Third, both CRREM and SBTi derive their decarbonisation curves from a grandfathering principle. Appendix B in the supplemental data online outlines five alternative ethical allocation approaches (e.g. equal per capita, prioritarian), but these are not quantified because no robust, published 1.5°C pathways exist for the building sector under those rules. Until such datasets become available, the tool remains aligned with the existing grandfathered trajectories.

Fourth, the tool currently supports only the 1.5°C scenario. This aligns with the Paris Agreement objective to limit global warming to well below 2°C, and preferably to 1.5°C, above pre-industrial levels. Although recent studies suggest that a 1.5°C overshoot may already be underway, it remains the most prudent and widely adopted target. Furthermore, the primary data sources, SBTi and CRREM, do not publish 2°C-aligned pathways. Producing such trajectories would require downscaling (IPCC) (2021–23) AR6 budgets through normative assumptions beyond the scope of this methods paper.

Fifth, the assumed 50-year reference study period presumes functional stability. In practice, buildings often undergo changes in use, which can significantly alter operational emissions. Future work could integrate adaptive reuse scenarios or probabilistic models of functional change.

Finally, because the tool is designed for architectural design applications, it does not assess whether an entire portfolio or city remains within the aggregate decarbonisation envelope implied by SBTi and CRREM.

Despite these limitations, the framework is, in the authors’ view, fit for purpose: a reproducible, early-stage translator of global carbon budgets into project-level targets that European design teams can apply in real time.

5. Conclusions

A methodological framework is presented for integrating 1.5°C-aligned carbon targets into architectural practice. By translating science-based targets into project-level metrics, it offers a structured means to assess and guide climate alignment in design.

This can stimulate critical discussion around absolute greenhouse gas limits for buildings and their applicability within the European context. Setting such limits is essential to align architectural practice with planetary boundaries. Yet voluntary targets within individual firms remain insufficient; widespread adoption will require embedding carbon budgets into design standards, client briefs and investment frameworks.

To foster transparency and uptake, the method is made available as an open Excel tool (Betti et al. 2025). This initiative also anticipates the forthcoming European Union policy landscape, where the recast Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EU/2024/1275; Council of the European Union & European Parliament 2024) mandates national CO2 limit values for new buildings by 2030. In this context, the framework represents an early contribution toward defining and testing such limits in practice, inviting collaboration and constructive critique from the wider design community.

Ethical approval

This research did not involve human participants, personal data or sensitive information, and therefore did not require approval from an ethics committee.

Acknowledgements

This research was undertaken within the Sustainability Team at HENN Architects—an architecture and design firm based in Germany with offices internationally—and benefited from the committed support and engagement of the firm’s leadership. The authors gratefully acknowledge the collective contributions from many colleagues within the office, whose commitment to climate-aligned design informed and shaped the work presented here.

Author contributions

Conception: G.B., I.S., D.B., A.J.H., E.K., S.S.; acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data: D.B., A.J.H., E.K., R.Y., K.A.; first draft: G.B.; revising the draft critically for important intellectual content: I.S., D.B., A.J.H., S.S.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare. At the time of submission, all authors were employees of HENN, the architectural practice in which the methodological framework described in this paper was originally developed for internal target-setting. The decision to publish was made independently of any commercial considerations and aimed solely to disseminate the approach for academic and professional use.

Data accessibility

The calculator and input data sources are provided in the supplemental data online. All cited datasets and pathway sources (CRREM, SBTi) are referenced; additional project-level examples are also in the supplemental data online.

Supplemental data

The supplemental data for this article can be accessed at: https://doi.org/10.5334/bc.664.s1