1. Introduction

Despite widespread recognition that public engagement enhances resilience and wellbeing in communities, how civic engagement is practised in the context of planning remains underexplored. Yet these limited engagements are often used to guide spatial and policy decisions (Purohit et al. 2024: 2). Focusing on the Cambridge Room (CR), a recently opened experimental urban room (UR) in Cambridge, UK, this paper highlights ‘curatorial’ as a process of knowledge production and negotiation (McKeon 2022; Richter 2023; von Bismarck et al. 2012; von Bismarck 2016) and interrogates how co-curation, as a mode of community engagement, supports local collaborations while remaining attentive to diverse community knowledges and visions.

Both living labs (LLs) and URs are often presented as forms of civic engagement and spaces of knowledge exchange among practitioners, scholars, organisations, public administrations and local communities. LLs typically entail a user-driven innovation approach with heterogeneous stakeholders (Malmberg & Vaittinen 2017; Sachs Olsen & van Hulst 2024), with urban living labs (ULLs) adopting a more situated focus on local urban planning, governance, and the role of citizens in the process of decision-making (Aernouts et al. 2023; Voytenko et al. 2016; Viano et al. 2023). As an alternative version of ULLs (Purohit et al. 2024) and a ‘dialogical space’ within the ULL system (Akbil & Butterworth 2025), URs in the UK are designed to stimulate discussions on urban futures in a physical or virtual space ‘where people could find out about the history of and future plans of their area’ (Farrell 2014: 48; Tewdwr-Jones et al. 2020; Urban Room Network 2022).1 Although they vary, the shared aim of ULLs and URs is to strengthen citizens’ involvement in response to local policies and challenges (i.e. related to natural, social or built environments) and to enhance civic resilience (Voytenko et al. 2016: 47).

Amid an ‘ascendant participatory culture’ (Huybrechts et al. 2017), terms such as co-design and co-creation have become commonly associated with processes of engagement in ULLs and URs, emphasising the democratisation of discourse in decision-making and knowledge production. However, scholars (Herberg 2022; Riding 2021) have started to raise concerns about these methods being deployed as an outcome-oriented strategy for hidden institutional purposes rather than fostering genuine collaboration. This pitfall of participatory approaches as mere ‘rhetorical devices’ (Nikonanou & Misirloglou 2023: 33), a ‘thin veneer of participation’ (Smith-Carrier & Van Tuyl 2024: 55), resonates with the lingering struggle for navigating between citizen power and tokenism as suggested in Arnstein’s ladder of participation (1969). In order to address this tension, some scholars emphasise ‘ethics of care’ (Tronto 2019) in generating transformative relations and moving beyond the output-oriented model.

In curatorial studies, more inclusive practices have emerged amid the ‘civic turn’ in cultural institutions (ICOM 2022; Nikonanou & Misirloglou 2023), where the curatorial encompasses not only the production of exhibitions but also the practice of generating knowledge and enquiry (Fernández 2011: 40). In planning, discussions on (co)curating the city have been explored in several studies (Kampelmann et al. 2018; Trentin et al. 2020; Melhuish et al. 2022) but (co)curatorial practices remain underexamined as an approach.

Building on these discussions, this paper uses the CR as a case study to critically examine the forms and dynamics of co-curation in URs. Drawing from three specific CR projects, this research asks: in which form, to what extent, at what stage and how can co-curation strengthen civic engagement in planning?

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews literature on civic engagement and curatorial practices, and the similarities and differences between co-design, co-creation and co-curation. Section 3 presents the findings and Section 4 provides the conclusions.

2. Literature review

Community collaboration and engagement are often seen as an antidote to the technocratic nature of decision-making and the epistemological injustice caused by the exclusion of certain knowledges and imaginaries (Chilvers et al. 2018; Escobar et al. 2014: 91). Scholars have suggested that participation is a fundamental human need and an important role in civic empowerment (Max-Neef 1991; Moynat & Sahakian 2024), while the ability to participate in a society serves as a ‘satisfier’ that fulfils the needs of its members (Guillen-Royo 2018).

For architects and planners, participation and civic engagement have become increasingly pivotal since the 1960s, with debates varying from specific urban problems (e.g. public housing, environment, safety) to critical examinations of participation practice and community collaboration itself (e.g. intentions, methods, power dynamics). In the context of ULLs, there is a general understanding that engaging residents as end users ensures that changes and solutions for the problems respond to local needs (Juujärvi & Pesso 2013). However, the effectiveness and extent of changes that ULLs can contribute depend directly on which actors are involved and how they participate (Puerari et al. 2018; Voytenko et al. 2016: 48).

This poses questions over the generic ways of operating in ULLs and other similar civic engagement contexts, where the politics and frictions of differences among stakeholders are often avoided (Akbil & Butterworth 2025: 545; Oldenhof et al. 2020; Sachs Olsen & van Hulst 2024: 996) and more attention is needed on the dynamics of engaging and dealing with diverse narratives. Recent practices have echoed these critiques and explored new ways of how the collaboration can be operated. Sachs Olsen and van Hulst (2024) have used the concept of ‘applied theatre’ to suggest a paradigm shift from ULLs to urban drama labs through participatory performance, in which citizens become active actors.

This call for a more inclusive practice and a critical examination of the politics of knowledge production resonates with the recent ‘civic turn’ in cultural institutions and curatorial studies. This turn is manifested through an array of community engagement initiatives and discussions (ICOM 2022; Nikonanou & Misirloglou 2023).2 Tate Exchange, for example, was a participatory programme at London’s Tate Modern and Tate Liverpool between 2016 and 2021 that aimed to offer a civic space for dialogues and ideas related to local and wider context with invited organisations, scholars, artists and groups to curate their own programmes within the Exchange space (Cutler 2018; Ride 2020).3 Central to this discussion is the role of ‘curatorial’. For German scholar Beatrice von Bismarck (von Bismarck et al. 2012: 7; von Bismarck 2016), curating is not only about a mode of representing or displaying but about ‘enabling, making public, educating, analysing, criticising, theorising, editing, and staging’. Hans Ulrich Obrist and Ed McKeon have drawn attention to the etymological roots of curating in the Latin word curare (to take care) (McKeon 2022; Obrist 2015). Highlighting curator as a proxy of care, the notion of care in curatorial practice has experienced a shift from ‘pastoral care’ through institutionalisation (Foucault 2009) to ‘caring for one another’ in which ‘we are all curators’ (McKeon 2022: 177–181).

For Fisher and Tronto (1990: 6), caring is to ‘maintain, continue, and repair our “world”’ through an interwoven web that ‘entails the political dimensions of power and conflict, and necessarily raises practical and real questions about justice, equality, and trust’. Drawing upon Tronto’s ‘ethic of care’ (1993; 2019), curator Sascia Bailer (2024: 208–216) has reflected on writings by urbanists such as Doina Petrescu and AbdouMaliq Simone and explored the concept of caring infrastructures as a relational curatorial practice that provides a support structure for marginalised groups. The notions of relationality and plurality are often foregrounded through a feminist perspective (Choi et al. 2023; Parsons et al. 2021; Samanani 2024). This attentiveness towards others and their concerns as not only a moral commitment but a relational practice suggests an ecological understanding of the wider world (Tronto 1993: 127–130). These examinations of curatorial move beyond exhibition-making and show curating as a relational practice of caring, especially in socially engaged curatorial practices, or a ‘battlefield of different positions’ that responds to diverse narratives and politics of knowledge production (Richter 2023: 91). Both strands of understanding extend the exploration of curatorial to other fields (e.g. planning) in pursuit of inclusive and transformative engagements (Kampelmann et al. 2018; Richter 2023: 337).

Emphasising the role of curatorial in articulating knowledge and in dealing with conflictual values, Kampelmann et al. (2018) propose a curator-planner approach to create a dialogical space bringing diverse actors together in a series of participatory workshops on urban transition. While the approach seeks a balance between individuals’ interests and the holistic system, Kampelmann et al. (2018) reflect on two potential pitfalls at stake: a tendency for certain forms, groups, ideas without critically scrutinising the ‘collective’, and a predefined hierarchy due to the invisible power of curator-planner as a ‘guardian’ or ‘caretaker’ (Kampelmann et al. 2018: 70). This view positions curatorial as an institutionalisation of pastoral care; however, this traditional framing has been expanded and challenged (McKeon 2022). Recent discussions on curatorial by urban scholars have considered (co)curating as an artistic practice of managing and producing museums, archives and pavilions (Trentin et al. 2020) or as a strategy for universities to engage with stakeholders (Melhuish et al. 2022). Choi et al. (2023) argue that the logic of full care through curating as experimenting and co-creating can lead to a generative form of participatory engagement in urban placemaking, prioritising coexistence rather than institutional agendas. How curatorial, as a methodological framework and a practice of caring, responds to the dominance of power and registers diverse positions in civic engagement require more a nuanced and critical understanding. In the next subsections, this paper examines current co-methodologies (namely, co-design and co-creation) before proposing a co-curatorial approach in urban civic engagement.

2.1 Co-design and co-creation

Co-methods such as co-design and co-creation are seen as powerful tools to involve diverse local communities in the process of decision-making and knowledge production (Baibarac & Petrescu 2019; Combrinck & Porter 2021; Nguyen et al. 2024; Puerari et al. 2018; Slingerland & Wang 2024). Yet these co-methods could also become tokenistic (Smith-Carrier & Van Tuyl 2024; Voorberg et al. 2015) or ‘ostentatious terms’ (Nguyen et al. 2024: 2). This section examines co-design and co-creation as methods of participation: while the former is solution-oriented, co-creation draws more attention to the process (Lissandrello & Morelli 2017).

2.1.1 Co-design

Sanders and Stappers (2008: 6) argue that co-design can be seen as a design-driven process in which designers (with creativity) and users (untrained) work together in the design development process. This perspective suggests a presumption strengthened by an underlying knowledge hierarchy between ‘experts’ and ‘laypeople’ that deviates from the participatory core of co-design (Belfield & Petrescu 2024; Knickel et al. 2023; Sanders & Stappers 2008). More recently, the emphasis has been shifted towards centring ‘the language of the ordinary’ (Combrinck & Porter 2021: 3) and the users’ lived experience, imagination and needs (Cataldo et al. 2021; McKercher 2020; Steen 2013). Co-design approach has been applied in various disciplines such as business management (Salmi & Mattelmäki 2021), health care (Greenhalgh et al. 2016; Palmer et al. 2023), computer science (Barrett et al. 2013; Uğraş et al. 2022; Wang et al. 2022) and the environmental sciences (Lupp et al. 2021). In planning and the built environment, co-design is often devised for developing technology-based tools, knowledge-based practices and community-based strategies for neighbourhood resilience (Baibarac & Petrescu 2019; Belfield & Petrescu 2024), green space (Nguyen et al. 2024), tourism design (Smit et al. 2024) and infrastructure development (Lupp et al. 2021; Viano et al. 2023). True co-design occurs from the start, though the term is often loosely used as shorthand for ‘participatory’.

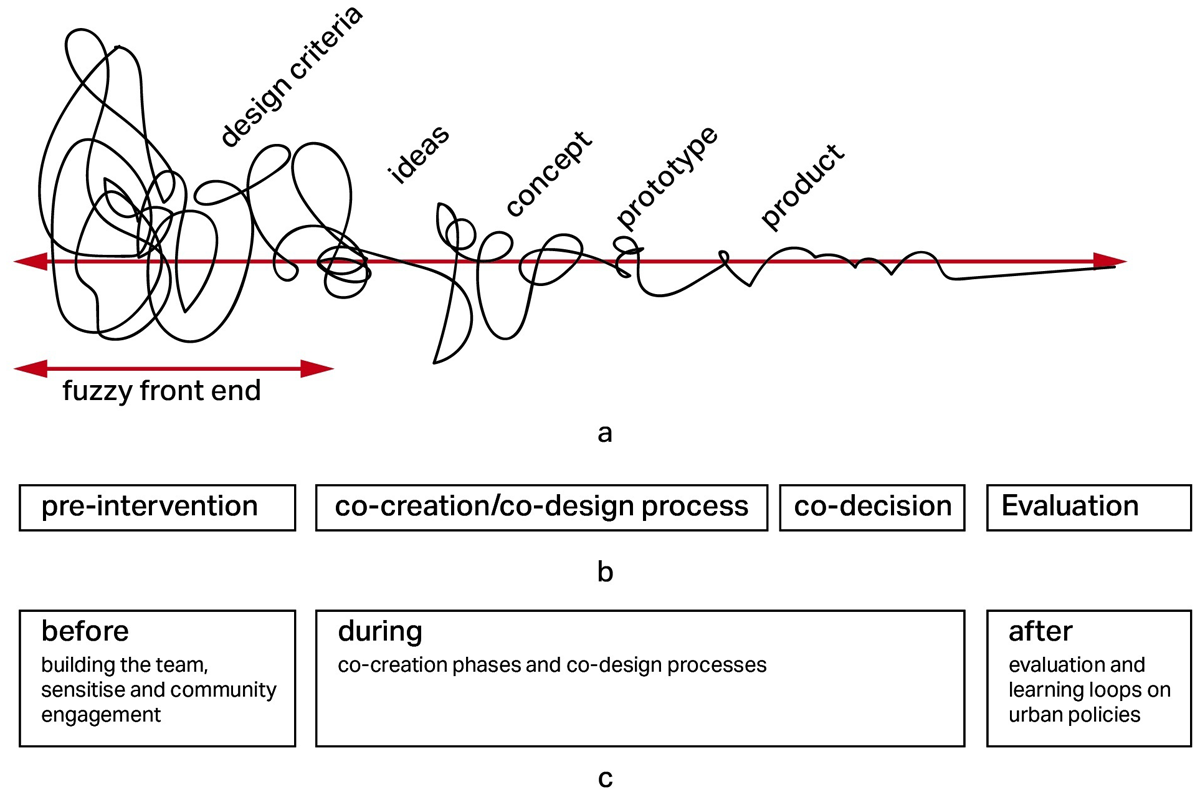

Slingerland and Wang (2024: 4–7) point out that limitations of co-design include an imbalanced power dynamic, heavy workload and constrained resources (Slingerland & Wang 2024: 7–8). These resonate with other scholars’ concerns over co-design (Palmer et al. 2023; Sanders & Stappers 2008) such as its end-oriented approach for efficient and collaborative solutions. As shown in Figure 1a, the initial stage of the co-design process tends to appear ambiguous. Identified as a ‘pre-intervention phase’ (Nguyen et al. 2024: 8–9) (Figure 1b) and a ‘before’ stage of participatory roadmap (Lissandrello & Morelli 2017: 7) (Figure 1c), it is at this stage that the aims and methods of the project are formed. Similarly, questions such as ‘who has been involved’, ‘how have people been engaged’ and ‘what is to be designed’ are commonly addressed during this early stage and a more clarified process of this ‘chaotic front’ is increasingly needed (Sanders & Stappers 2008: 7; Palmer et al. 2023: 2). The power dynamic of co-design can prioritise ‘certain individuals or interests at the expense of others’ (Slingerland & Wang 2024: 7), and the common prejudice of considering citizens to be untrained service-receivers (Sanders & Stappers 2008: 6; Voorberg et al. 2015: 1342) can lead to an unequal relationship and limited opportunities of transformation (Palmer et al. 2023).

Figure 1

Temporal sequences and phases typically used in co-design and co-creation processes, drawn from the literature review.

Note: a = co-design, adapted from Sanders and Stappers (2008); b = co-creation and co-design, adapted from Nguyen et al. (2024); c = co-creation and co-design, adapted from Lissandrello and Morelli (2017).

2.1.2 Co-creation

The definition of co-creation varies in different disciplines. Sanders and Stappers (2008: 6) position co-creation as an overarching concept that covers ‘any act of collective creativity’. Riding (2021: 5), writing from the perspective of museology studies, frames co-creation as ‘creating an output together’. In public policy, co-creation is used to describe collaborative processes aimed at the ‘creation of sustainable relations between government and citizens’ (Herberg 2022: 24; Voorberg et al. 2015: 1340), in which the notion of creativity is less stressed. Despite definitional differences, there is a commonly shared theme of co-creation as an active involvement of citizens in the process of production (Voorberg et al. 2015: 1335). This process-focused nature emphasises capacity building, dialogic interactions and long-term effects that move beyond the solution-oriented scope of co-design (Lissandrello & Morelli 2017: 5–11), whereas the latter can be seen as a component of co-creation (Nguyen et al. 2024: 3).

The process-oriented and open-ended nature of co-creation is often celebrated for its capacity and context-based flexibility to produce unexpected impacts and new possibilities (Herberg 2022: 26; Lissandrello & Morelli 2017: 11; Massari et al. 2023: 20). Yet such openness can also invite manipulation or create false expectations as to advance institutional agendas (Herberg 2022: 26). In such cases, there is a risk that co-creation becomes a technocratic tool and a service ‘that can be bought and sold’, rather than a space for real inclusive and emancipatory practices (Greenhalgh et al. 2016: 410; Herberg 2022: 26). Co-creation is often linked with the idea of unleashed collective creativity (Herberg 2022: 29), where value emerges through shared knowledge and mutual learning (Riding 2021: 2).

Seeing it as a collaborative practice for transformative changes, Herberg (2022: 30) situates co-creation within a shifting system of societal engagement between governance and affected communities. This engagement, which Chilvers et al. (2018) term ‘ecologies of participation’, suggests a complex sociopolitical dynamic with internal contradictions that raises questions such as ‘who is (included and excluded in) the collective’ (Herberg 2022: 33–34). Scholars in design theories (Gray & Kou 2019: 42) have pointed out that co-creation is largely constitutive of the designers themselves. Further, institutions and organisations can be concerned about losing control in the process or seeing citizens not as equals (Voorberg et al. 2015: 1342). Resonating with the limitations of co-design, the result is that this authoritative nature of technocratic and institutional practices frequently reproduces the very hierarchies and barriers to co-creation (Riding 2021: 5).

2.2 Co-curatorial approach in civic engagement

Addressing the invisible power of a curator, Forde (2021: 110) proposes co-curating as a collective practice between the curator and the artist that challenges institutional structures and normative practices. This suggests a co-authorship with various agencies that aims not at creating something together within a predefined structure but at ‘co’identifying problems and opportunities, ‘co’defining the methods and rules and ‘co’taking care of a project and/or a space from an early stage of engagement (Choi et al. 2023: 24; Nikonanou & Misirloglou 2023: 34). Co-curation aims to generate a fluid, active space that remains open for multiple agents of care and allows different ways of doing and knowing (Cranfield & Mulvey 2023). This presence of various narratives and forms of knowledge defines co-curatorial as a field of negotiations that needs to be scrutinised. Iervolino (2023) positions co-curating as part of co-creation in visualising minoritised communities, such as trans people, while demonstrating the challenge and importance of being attentive to intragroup divisions within the co-curators, as well as the tensions between individuality and a collective goal.

Kampelmann et al. (2018: 61–62) argue that a curator-planner is characterised and guided by three principles: knowledge (engaging with diverse ways of knowing), actors (dealing with various stakeholders) and scales (navigating between individuality and the holistic planning goal). Building on this but shifting from the figure of one curator to a co-curatorial approach, this paper proposes four interwoven dispositions of the co-curatorial approach in civic engagement: knowledge co-production, multiple agents of care, multiple scales and a process focus:

Knowledge co-production

Understanding curatorial as a form of research that interprets, documents, and articulates various viewpoints and approaches (Richter 2023; Sheikh 2013), co-curatorial enables different actors to participate in knowledge production. Their role is not passively providing information but actively defining the scope, methods and media of producing and presenting. The emphasis of engagement shifts from giving and receiving to ‘curating with’ (and thus ‘caring with’), which fosters solidarity and challenges the existing asymmetrical power dynamic (Tronto 2013: 154; Tronto 2019: 31–32). This feeds into the current critique on epistemological assumptions that are less addressed in the ULL approach (Baxter 2022).

Multiple agents of care

Knowledge co-production suggests a temporary alliance of ‘agents of care’, whose diverse views resist a typically exploitative model of engagement (Fitz & Krasny 2019: 16). On the one hand, the ‘agents of care’, including planners, architects, organisations, residents and other grassroots initiatives, imply a collective care by ‘thinking of citizens as both receivers and givers of care’ (Fitz & Krasny 2019: 16; Samanani 2024: 3; Tronto 2013: 35). This notion of ‘caring with’ and ‘curating with’ foregrounds a collective responsibility for all agents of care, although this can associate with ‘unvoiced disagreement’ (Iervolino 2023: 129). As scholars (Choi et al. 2023: 21; von Busch & Palmås 2022: 286) have pointed out, an ‘obsession for participatory solidarity’ with decentred groups can lead to another form of continued centralisation of power, so diverse agents of care need to be responsible for not only their own needs but a careful consideration of those of others (Tronto 2019).

Multiple scales

This notion of plurality leads to another key characteristic of co-curatorial, which is the multitude of scales. Geographically, considering the complexity of an urban system (e.g. planning, infrastructure, climate), this disposition becomes crucial in the urban context as these multiple agents of care can be from neighbourhood, urban, suburban or regional contexts (Kampelmann et al. 2018: 62). Structurally, within this ecology of participation (Chilvers et al. 2018), there is a need for critical scrutiny to understand the connections, conflicts and negotiations between individuals and collective, as well as their diverse perceptions, powers, skills and limitations related to the multitude of scales. At the same time, drawing attention to scales allows co-curatorial to be practised in a manageable way.

A process focus

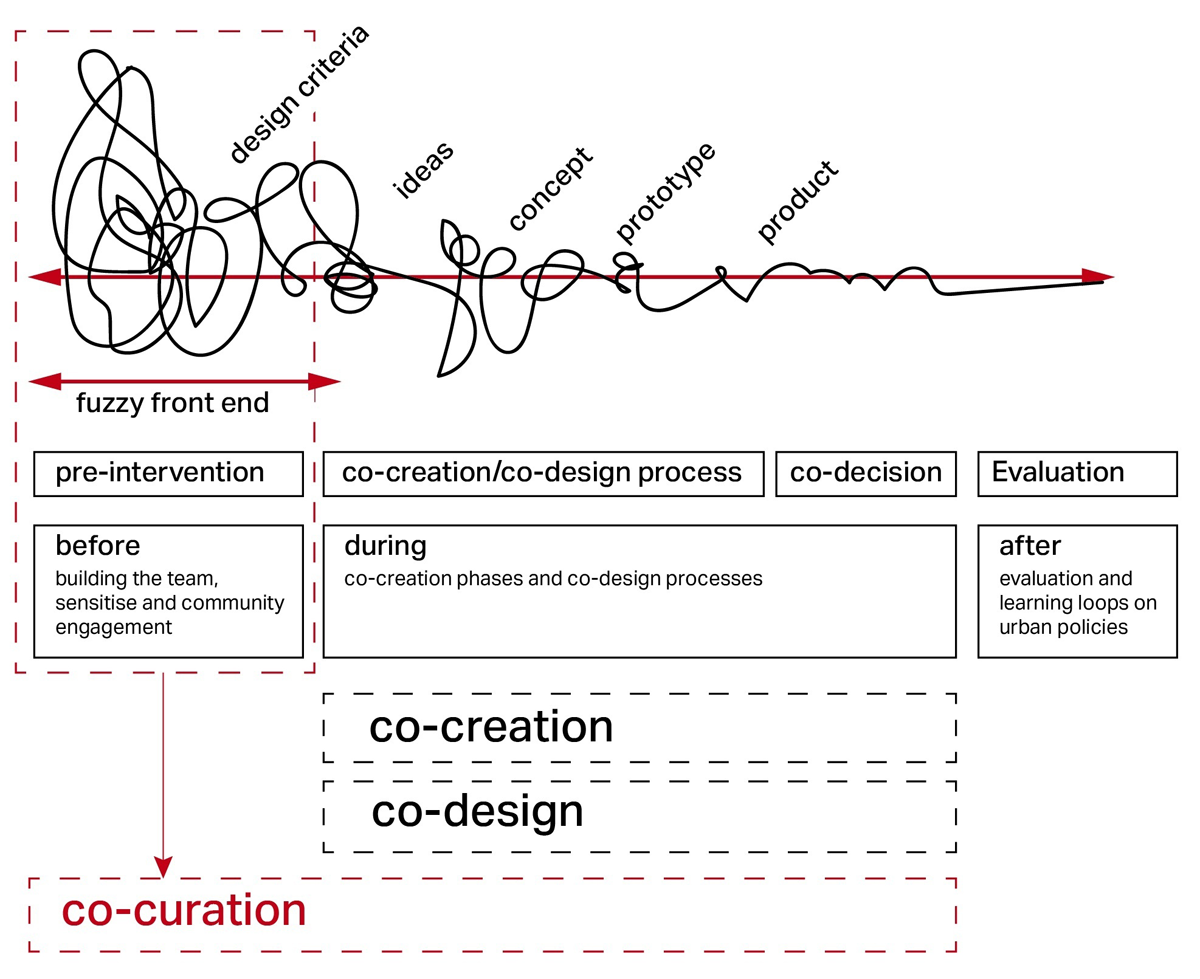

Beatrice von Bismarck (2012: 7; 2016: 22) views curatorial as a continuous process of negotiation in which the positions and directions constantly vary and emerge. Hierarchies become temporary in this process of constant renegotiation and contestation (O’Neill 2016). In this regard, co-curatorial responds to the predefined structural dominance and injustice. As shown in Figure 2, the involvement of various actors as co-curators at an early stage registers the fuzzy front that is often overlooked in co-design and co-creation (Sanders & Stappers 2008) and, arguably, shows a tendency to sustain long-term collaboration and engagement – a challenge in ULLs and other settings (Ebbesson et al. 2024: 425–426).

Figure 2

Different phases of involvement for co-curation, co-creation and co-design.

Sources: Adapted from Sanders and Stappers (2008); Nguyen et al. (2024); Lissandrello and Morelli (2017); expanded by authors.

3. Findings: the Cambridge room as a case study

Situated in one of the most unequal cities in the UK (Sunikka-Blank et al. 2022), the CR is a practice-led research project focused on community consultation and aiming to widen participation in planning. The project draws upon learnings from a previous project, the Community Consultation for Quality of Life (CCQoL) (Lawson et al. 2022; Purohit et al. 2024). Through a UR approach, the CCQoL project revealed the urgent need for spaces to share knowledge across communities, convene new kinds of conversations and share old narratives as a foundation for new imaginaries (Kaika 2010).

The CR originated as a three-year research project in 2023, funded by the University of Cambridge, and later established itself as an independent charitable organisation in September 2024. The CR is governed by a board of eight trustees, representing a range of expertise and institutional affiliations including elected councillors from Cambridge City Council and South Cambridgeshire District Council, the Cambridge Association of Architects, and academic and professional experts in planning.

Following a framework developed in CCQoL, the CR is supported by a Local Advisory Group (LAG) with 25 members, including professionals, public administrations, University scholars, local organisations, artists and community groups. The CR is built on an existing UR initiative developed by the Cambridge Association of Architects in response to the rapid growth of the city and increasing rates of inequality, including a 12-year gap in life expectancy within the city (Bakshi 2025). With the establishment of the government-backed Cambridge Growth Company (UK Gov 2024), the pressure for the city to grow economically has been exacerbated, raising concerns that local communities will be left further behind.

The CR’s remit covers the Greater Cambridge and Peterborough Combined Authority, straddling the wealth of the city centre and the considerably more deprived rural areas surrounding it. Since March 2025 the CR has been operating within the Grafton Centre retail centre pop-up space (see Figure 3), attracting almost 2,000 visitors in its first six months through a series of community-led events facilitated by researchers and volunteers.

Figure 3

The pop-up space of the Cambridge Room, 2024.

Photos: Matthew Smith.

The following section examines three CR projects – the Living Atlas of Community Activism, Let’s Go Fly the Kite and The Book of Cambridge – to illustrate the co-curatorial approach. These projects employed mixed methods to collect information and engage with local groups, including semi-structured interviews, desk-based archival research, roundtable meetings and arts-based methods such as street theatre, performances, workshops and participatory mapping.

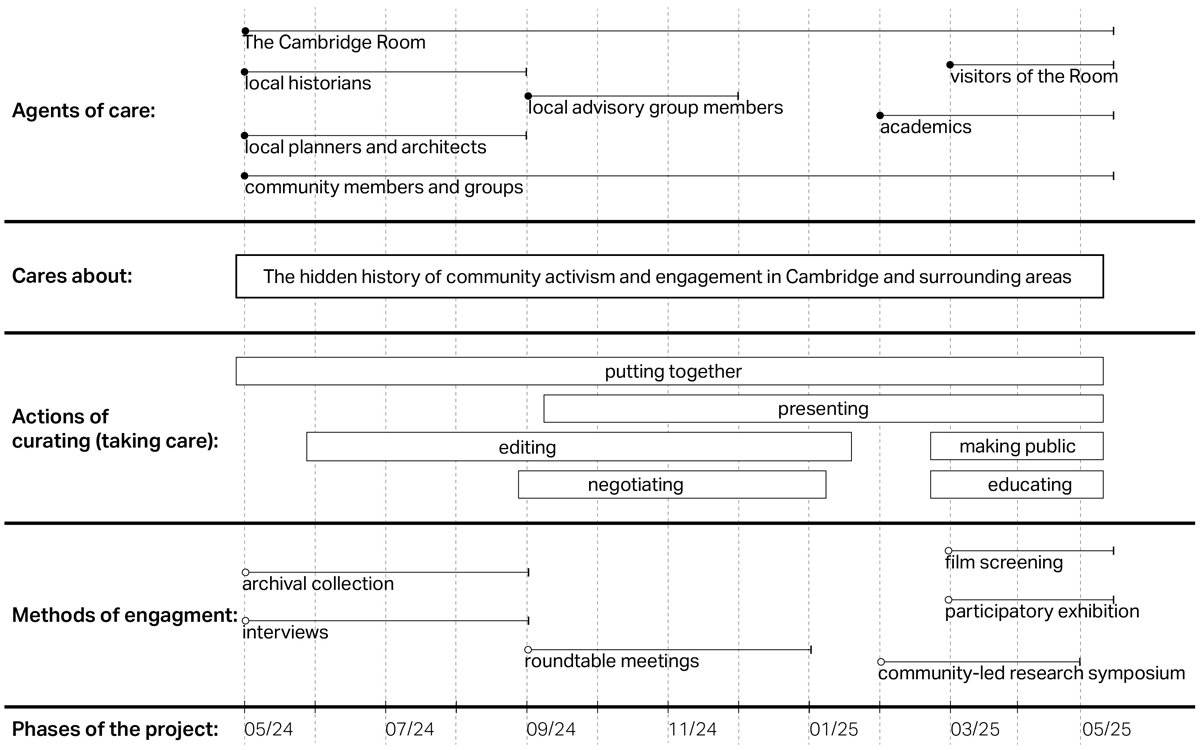

3.1 Living atlas of community engagement and activism

In several public CR events in early 2024, one question frequently raised by residents was on other groups in Cambridge that share aims similar to that of the Cambridge Room. Many local initiatives – such as Cambridge Architects Association, Capturing Cambridge, Cambridge Carbon Footprint and Transition Cambridge – are founded by community members who have been maintaining, transforming, capturing, imagining and repairing different aspects of the city.

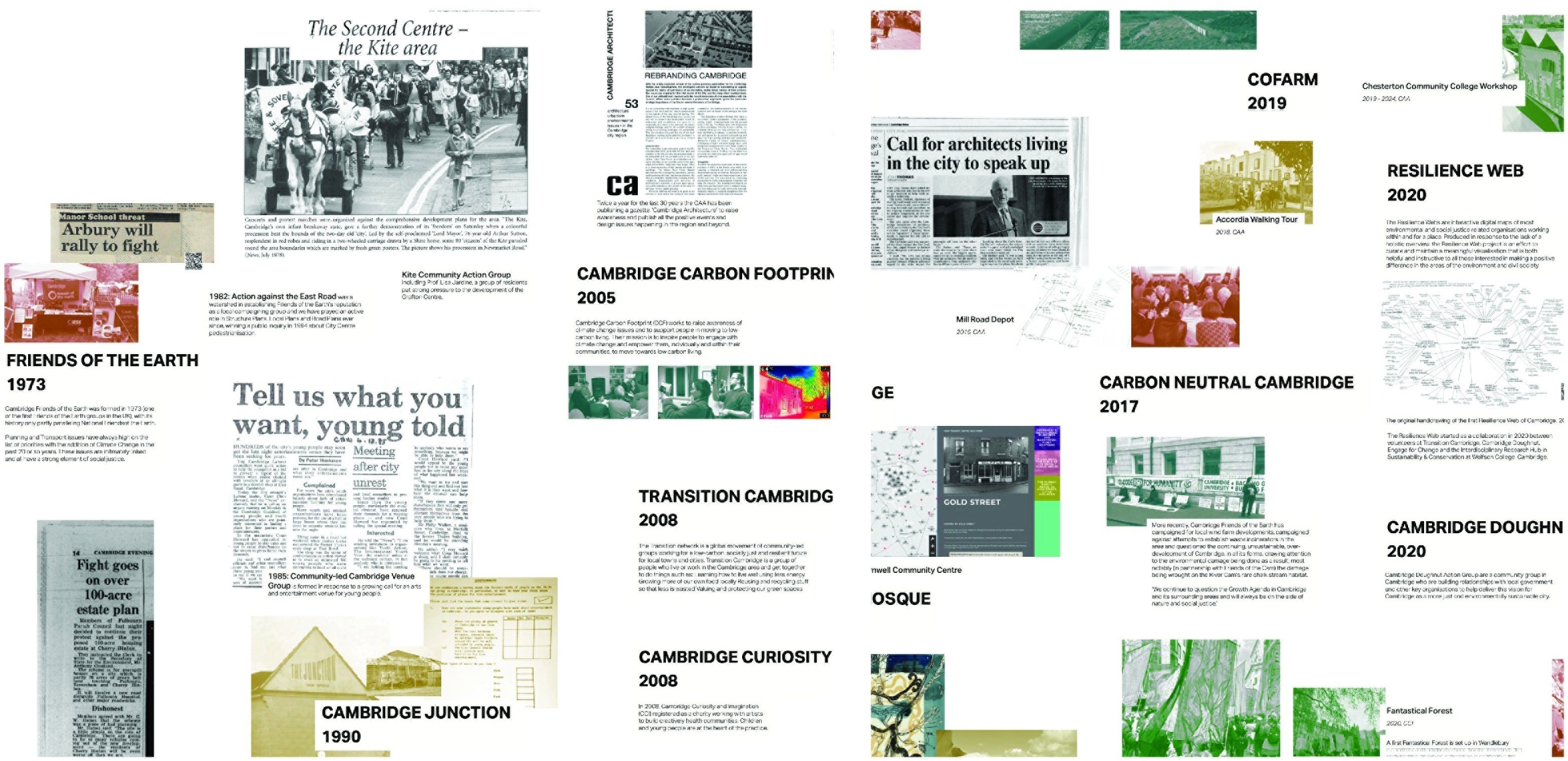

Between May and September 2024, a series of in-depth interviews were conducted with 22 local historians, artists, archivists, scholars, community groups and organisations to understand the history of community engagement and activism in relation to the built environment in Cambridge and its surrounding rural and natural areas. Echoing the UK’s Arts and Humanities Research Council project Spaces of Hope: Peoples’ Plans on past practice, which responded to planning from grassroots level (Brownill 2021; Inch 2023; Peoples’ Plans 2023), the data collected from the interviews and archival research resulted in a timeline of community activities and projects since 1927 (see Figure 4). This timeline, titled Living Atlas of Community Engagement and Activism, includes information on the projects, groups, sites, methods and outcomes.

Figure 4

Details on the Living Atlas of Community Engagement and Activism, 2024.

Figure 4 shows that the groups and projects presented in the Atlas vary from recent children’s art workshops to community protests in the 1970s, collected through interviews and archival materials (leaflets, posters, news reports, photos and drawings), donated by community members or collected from local archives such as Cambridgeshire Collection and East Anglian Film Archive. Fragmented and ever-evolving, the Atlas does not predefine a specific theme or scope. The Atlas invites the CR visitors to add more projects and groups not presented on the board (see Figure 5), evolving with an open-ended perspective through a process of co-creation (Nikonanou & Misirloglou 2023: 34).

Figure 5

Living Atlas of Community Engagement and Activism, before and after the opening of the Cambridge Room.

In contract to many co-creation projects, the voices of community groups were included from the very start. By decentralising the curatorial process, the contribution of local groups is realised not merely by adding their knowledge onto a structured canvas but through actively negotiating the theme and scope of this timeline as co-curators (see Figure 6). For instance, during one LAG meeting, members suggested introducing the shifting policies of urban planning in different periods to contextualise urgency and impact of these grassroots projects. A local council member proposed adding city council public engagement projects but this was objected to by other LAG members, as the focus of the Atlas is on activism and engagement initiated by grassroots groups. This suggests a complex power dynamic around the table and a shift from an oversimplified distribution of voices to a nuanced form of ‘dialogue + deliberation’ (Escobar et al. 2014: 92–95). Yet positionality is present. Some community organisations stated no support towards the CR owing to its university affiliation, yet they were willing to be included in this collective atlas.

Figure 6

Co-curation process of the Living Atlas.

Since its opening, the Atlas has become a key feature of the pop-up space. One visitor noted: ‘It is a very good way to introduce the Cambridge Room and learn about the history of the city.’ The Atlas offers an ‘entry-point’ (Ride 2020) for visitors to access the complex history of community activism in Cambridge and to engage with the topic of city-making and key issues in the area. It also becomes an index of community groups and projects; for example, it helped identify speakers and projects for a May 2025 symposium on community-led research.

3.2 Let’s go fly the kite

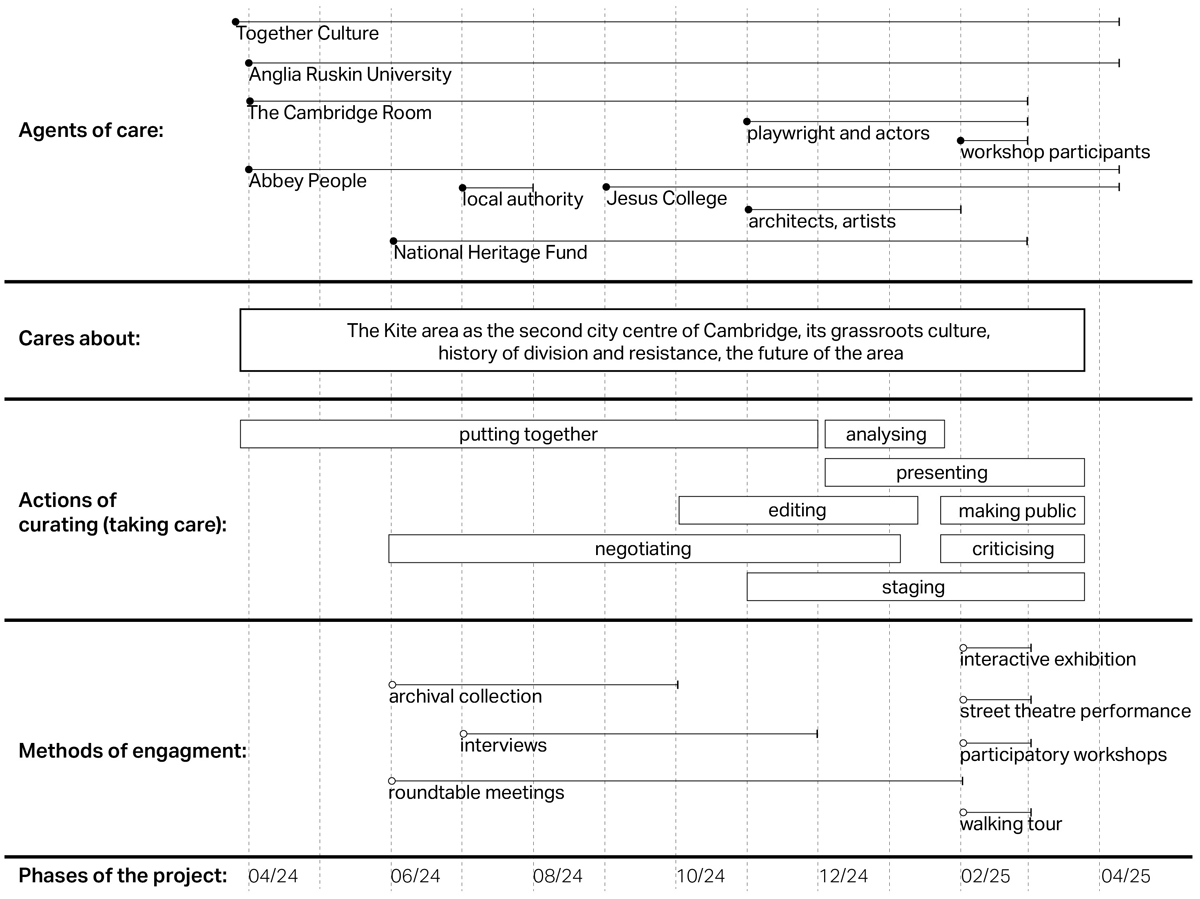

In 2024, Together Culture, a community interest company, in collaboration with the CR and other partners, successfully received funding from the National Heritage Fund for a community development project, Let’s Go Fly the Kite. The project aimed to rediscover the hidden history and reimagine the future of the Kite area, a historic Victorian neighbourhood east of Cambridge’s city centre. In the 1970s, a pressure group engaged all residents, regardless of background, to oppose the city council’s bulldozing approach of replacing terraced housing with retail development. With many former residents relocated in the 1980s to Arbury and Abbey, today two of the city’s most deprived wards (Cambridge City Council 2024), much of the area’s history had faded from public memory.

The goal of Let’s Go Fly the Kite was to work with historians and residents to unveil local visions of the area. Ten ‘story finders’ from local communities were recruited and collected 115 interviews, which were archived and analysed by the other academic partner from Anglia Ruskin University (Tsenova et al. 2025).4 Three themes emerged from the interviews – land, power and change – reflecting historical tensions between town and gown. The CR collaborated with Together Culture to organise a series of public conversations and workshops to discuss the findings with a wider audience. Prior to the workshops, the initial theme of ‘town vs gown’ was challenged by CR members and an archivist, as the history of the Kite itself suggests a complex relationship that goes beyond opposition and division.

These conversations, titled What Are We Talking about When We Talk about Town and Gown, also involved a playwright and three local actors to play historical figures related to the themes of land, power and change. The role of the CR shifted from lone curator of an exhibition to co-host of a public programme (see Figure 7).

Figure 7

Co-curation in the Let’s Go Fly the Kite project.

Through theatrical performances, participants were engaged in a situated setting with staged conflicts and open-ended dialogues. This experimental, loosely structured collaboration enabled the programme to reach a wider audience who may be overlooked in a typical academic and social engagement and whose visions may be completely different. While some resonated with the town vs gown division, one participant from an academic background was strongly opposing the division as ‘there was more connection than division’. The conversations were far from neutral territory (Cranfield & Mulvey 2023: 5), echoing Cedric Price and Hans Ulrich Obrist’s (2009: 50) assertion that the very idea of curating a neutral space is ‘nonsense’ if one realises the coexistence of all personal experiences. Instead of a more orchestrated conversation with a notion of sharedness (Sachs Olsen & van Hulst 2024: 1005), this pluralistic nature of the conversations led to unexpected conflicts, challenging questions, and disagreements; it also revealed valuable insights, which have fed into a larger funding application for community groups (Together Culture and Abbey People) and a civic report by Cambridge University.

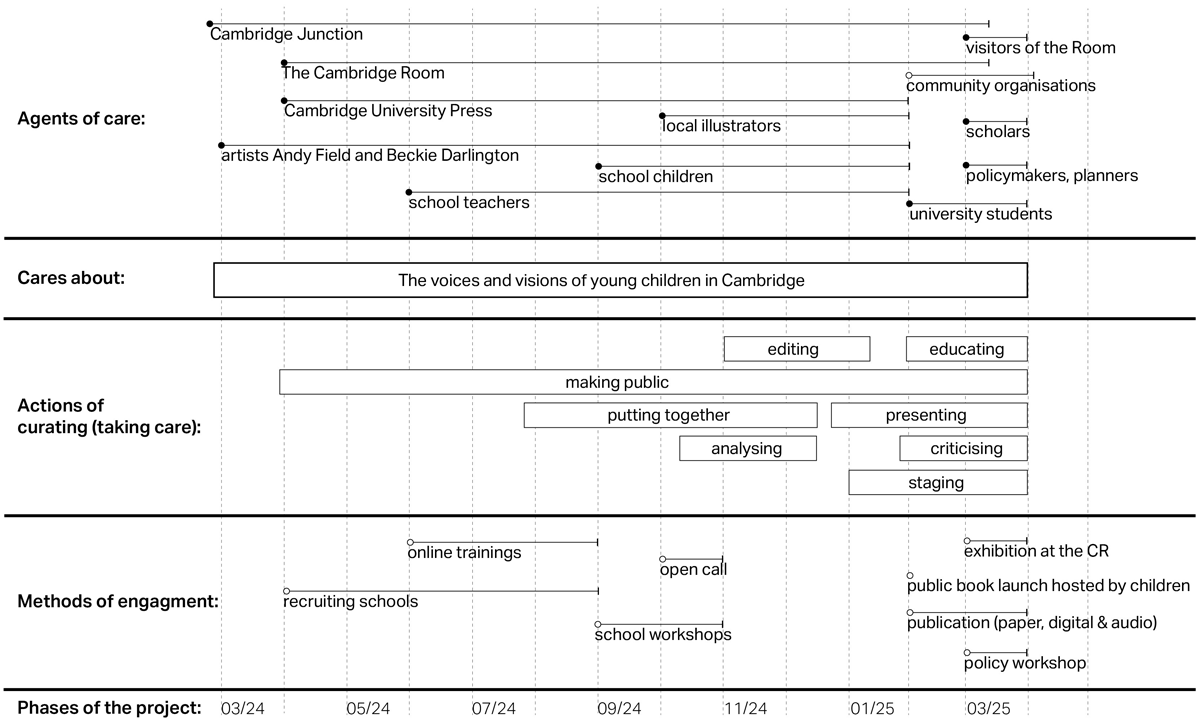

3.3 The book of Cambridge

In September 2024, the CR and Cambridge Junction, a local charity and cultural venue, announced an open call for The Book of Cambridge (2025).5 As a guidebook ‘made for adults’, the project was initiated by Cambridge Junction in collaboration with artists Andy Field and Becky Darlington, the CR, and Cambridge University Press & Assessment, and was co-created with over 100 local school children who approached the city through a different perspective. The illustrator helped children to visualise their knowledge and visions of the city (see Figure 8). The project aligned with a CR-organised children’s workshop, in which 259 drawings of Cambridge were produced and later exhibited at the pop-up space alongside The Book of Cambridge.

The maps of Cambridge by children pay less attention to the territories of the university and colleges. Instead, playgrounds, natural land, food stores, shopping centres and the ramp of their neighbourhood streets become prominent. As active meaning-givers to the environment around them (Jans 2004: 35), children offer various depictions of ecologies of the city at a micro and everyday level. The focus of the Book moves beyond the question of whether their visions are fantastical or feasible to create an instrument that allows potential dialogues and their views ‘being heard’ (Derr 2015: 127–129). In 2025, at a policy workshop on child-friendly Cambridge, with the Cambridge City Council Great Cambridge Shared Planning, the Book was raised as an example of a way to include the often-excluded views of local children for city planning. It became a learning instrument to educate planners, policymakers and scholars, who are often seen as the ‘More Knowledgeable Other’ (Vygotsky 1978).

Figure 8

The Book of Cambridge, 2025.

Illustration: Sally Walker.

The launch event – including booking signings and readings – was entirely hosted and run by young children, showing a deep trust between them and the Junction as a community venue. The Junction was an outcome of community activism led by a group of young people for more accessible cultural venues in Cambridge in the 1980s and their experience from youth-focused projects allowed trust for such a format to take place. The CR did not lead the project but collaborated with other agents of care (see Figure 9), providing resources (funding, networks, spaces, staff time), and sharing outputs with other institutions and policymakers. The collaboration introduced the CR to a different group of marginalised audience and, following the ‘educational turn’ (von Bismarck et al. 2012) of curatorial practice, the role of the CR became a learning space, not to reinforce the dominant voice of the expert but to diversify the voices and imaginaries (Riding 2021: 10–11). As shown in Figure 9, the open-ended nature of the co-curated project challenged the linear process of engagement, allowing new groups and dialogues at a later stage of the project, with the role of the CR shifting between facilitating, presenting, educating and criticising.

Figure 9

Co-curation of The Book of Cambridge.

4. Conclusions

Building on Kampelmann et al. (2018: 61–62) but shifting from the figure of one curator to a co-curatorial approach, this paper proposes four interwoven dispositions of co-curatorial in civic engagement:

knowledge co-production

multiple agents of care

multiple scales

a process focus.

The forms of co-curatorial processes employed in the three CR projects are not a fixed model but instead vary from participatory mapping, exhibitions, workshops, performances and publications. Through different tangible (i.e. books, maps, installations) or processual (i.e. relationships, conversations, knowledges) outputs, the city is documented through different perspectives, and through this process the notion of placeness and ‘growth’ is expanded.

Echoing von Bismarck (2012: 8), co-curating here is not merely about assembling diverse knowledge and views as part of engagement; it is also about enabling, staging, educating and making public, thus moving towards a collective action of care. Rather than a leading expert, the CR acts as one agent among multiple agents of care, acknowledging that the impact of co-curation depends on the willingness to decentralise authorship and resources, creating spaces that enable others to participate and curate – what Lefebvre might call reclaiming the co-authorship to the city as an ‘oeuvre’ (Lefebvre 1996: 207). The documentation and local expertise, elicited through arts-based methods and community networks, shape a more diverse image of a city to inform planning and improve social cohesion. This is achieved by amplifying the voices of overlooked groups, like children, and their narratives of the city, moving beyond simplistic, purely economic views of growth.

Co-curating starts at a much earlier stage than more typical and solution-oriented co-design and co-creation processes, addressing the ‘fuzzy’ front end in civic engagement (Sanders & Stappers 2008: 6–7) and the often-predefined roles and hierarchies of tokenistic engagement. As a dynamic process of negotiation, co-curating drifts away from the often-well-hidden pursuit of ‘only my own’ (Tronto 2013: 175). However, the process does not erase power imbalances; conflicts and disagreements between community groups or between communities and external stakeholders reveal the need for ongoing negotiations, care and attention to relational dynamics. For example, in Cambridge community groups have environmental agendas but other groups actively oppose the inner-city congestion charge – recognising such tensions is crucial to ensuring co-curation remain inclusive and reflective.

Despite these contextual limitations, the dispositions of co-curation identified here provide transferable insights for other URs and ULLs. By foregrounding care, dialogue, dynamics and collective responsibility across diverse scales and agents, the findings suggest that co-curation as civic practice can guide more inclusive community engagement in cities facing inequalities or rapid change. It is also important to note that, while in the CR projects policymakers, artists, schools and community organisations were connected and well represented, engaging commercial parties and developers remains more challenging, despite their significant influence over city planning. It is therefore an imperative to document evidence on the impact of co-curating to motivate commercial parties. Relevant indicators could include participatory numbers, demographic information, and impact on the planning process, as well as employee retention and recruitment in the area linked to an improved built environment and safer community.

Notes

[1] The term URs and relevant practices were boosted after the Farrell Review in 2014, while some studies had already identified concepts and models prior to Farrell, such as Geddes’s city museum (Tewdwr-Jones et al. 2020). In the UK, there are more than 15 URs, all with different forms, focuses, approaches and funding: some have a long history of community engagement and architectural education (for example Live Works in Sheffield and the Farrell Centre in Newcastle) and some focus on art and creative practitioners (Dover Urban Room).

[2] The International Council of Museums’s 2022 redefinition of the term ‘museum’ foregrounds an ethical and professional operation with the participation of communities (ICOM 2022).

[3] In 2020, author ZL organised a week-long participatory programme with workshops and screening at Tate Exchange Liverpool: https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-liverpool/knowledge-power-production-city.

[4] More details of the Kite project at https://www.togetherculture.com/navigator.

[5] The book is available as a digital file and an audio book: https://www.junction.co.uk/creative-learning/past-projects-archive/book-of-cambridge/.

Acknowledgements

The team would like to thank the community groups, residents, scholars, practitioners and local advisory groups who have supported the development of the Cambridge Room and contributed to the projects mentioned in this paper.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Data availability

Interview transcripts for the Living Atlas are not publicly available owing to privacy considerations. Anonymised data on the operation of Cambridge Room and workshop outputs are available from the authors upon request.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval for this project was granted by the University of Cambridge’s Ethics Commission. Feedback forms were anonymised. Photos and notes were collected with informed consent.