1. Introduction

Historic buildings are crucial to a city’s cultural heritage, reflecting its historical elements and population diversity. However, municipalities across Canada struggle with an alarming trend toward neglect, obsolescence and demolition of these buildings. According to the National Trust for Canada (2014), 23% of Canada’s old and historic buildings in urban areas have been demolished. Left abandoned, built structures are often subject to vandalism, theft and fire, rapidly deteriorating while maintenance costs continue to rise. The loss of historic buildings, for example, the Centenary Queen Square Church in Saint John, New Brunswick, in 2019, underscores the urgency of this issue (Webb 2019). In a recent article, architect and historian John Leroux draws attention to a broader societal failing, emphasising that the challenge extends beyond demolition and includes a disregard for the building industry’s maintenance and care of such cultural assets (Webb 2019). In his book The Lost City, Leroux describes urban renewal and the loss of heritage buildings as follows:

This isn’t just a story about the loss of streets and buildings, it’s about the loss of human energy and deep-seated connection with community.

The urgency of addressing these losses in New Brunswick has drawn increasing attention, leading to efforts to identify solutions within the province. On a global scale, adaptive reuse—the practice of repurposing ageing or abandoned structures for new uses—has proven to be an effective strategy (Bullen & Love 2011; Tam & Hao 2019; Vafaie et al. 2023; Yung & Chan 2012). Yung & Chan (2012: 352) describe adaptive reuse as:

a form of sustainable urban regeneration, as it extends the building’s life and avoids demolition waste, encourages reuses of the embodied energy and also provides significant social and economic benefits to the society.

Despite the proven effectiveness of adaptive reuse as a viable solution, numerous challenges remain to be addressed, and its integration into the field continues to raise significant concerns (Wiebe 2021; Othman & Elsaay 2018; Pintossi et al. 2021; Remøy & Van der Voordt 2014).

While some research in Canada has addressed these challenges, it has predominantly focused on the provinces of Ontario and Quebec, often overlooking smaller provinces such as New Brunswick, despite their rich stock of heritage buildings (Kovacs et al. 2015; Mowry 2024; Opher et al. 2021; Tyers 2021; Vecchio & Arku 2020). As such, this study explores the question: How are derelict heritage buildings at risk of demolition preserved through adaptive reuse in an urban setting in New Brunswick? To address this question, a multiple-case study approach focuses on cases in Moncton, Fredericton and Saint John, the province’s three largest cities (Yin 2009). It combines an information review and semi-structured interviews to identify strategies for overcoming barriers to adaptive reuse implementation in smaller cities. The study aims to recommend practices that promote adaptive reuse adoption, preserve New Brunswick’s architectural heritage and foster sustainability in construction.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 considers the policy context of heritage preservation in Canada and the research literature on adaptive reuse as a potential avenue to support heritage preservation while increasing environmental sustainability. Section 3 then presents the research design and methods. The results in Section 4 provide a detailed description of each case studied before presenting a cross-case comparison based on the results thematic analysis of interviews conducted with project stakeholders. The discussion in Section 5 highlights the importance of collaborative frameworks, innovative and strategic funding arrangements, expertise and building condition, and stakeholder roles in the success of adaptive reuse.

2. Research context and background

2.1 Heritage preservation: national and regional contexts

Heritage preservation means protecting historic buildings and sites that have been designated for their heritage value, to maintain their cultural, architectural and historical significance. Designated ‘heritage’ enjoys official recognition and special protection. The following sections examine heritage preservation frameworks in Canada and New Brunswick, with a focus on the distinct approaches of Moncton, Fredericton and Saint John.

2.1.1 Heritage preservation in Canada

Heritage preservation in Canada is based on a framework of federal, provincial and municipal policies aimed at protecting the country’s historic buildings. At the federal level, the Historic Sites and Monuments Act allows for the designation and funding of national historic sites (Government of Canada 2013). However, the federal government exercises direct control only over the heritage buildings it owns; the management and protection of other heritage properties primarily fall under the responsibility of the provinces and municipalities. The Standards and Guidelines for the Conservation of Historic Places in Canada, developed by Parks Canada, provide recommendations for maintaining heritage integrity while addressing contemporary needs (Parks Canada 2003). Although developed at the federal level, these standards serve as a reference for many provinces and municipalities in formulating their own preservation policies, thus ensuring a certain degree of consistency in heritage management across the country, but they are not imposed on provinces and municipalities.

2.1.2 Heritage preservation in New Brunswick

In New Brunswick, heritage preservation is governed by the Heritage Conservation Act, which enables municipalities to identify, designate and regulate heritage properties (Government of New Brunswick 2012). The major cities of New Brunswick—Moncton, Fredericton and Saint John—each possess unique historical and architectural contexts that shape their respective approaches:

Moncton developed in the 19th century as an industrial hub for the railway and fossil gas industries. Its pragmatic and functional architecture reflects its industrial origins. The Heritage Conservation By-law, supported by a Heritage Conservation Committee that advises on preservation efforts, protects historic buildings from demolition and ensures that alterations to their exterior aesthetics comply with federal standards (City of Moncton, n.d.). The city also offers heritage grants to support restoration that aligns with national standards.

Fredericton, the provincial capital since 1785, developed as an administrative and educational centre. Its architecture, including institutional and industrial structures, reflects this heritage. The Heritage Preservation By-law protects historic districts, notably the St. Anne’s Point area, while the Heritage Preservation Review Committee ensures compliance with standards and guides compatible developments (City of Fredericton n.d. a). Incentives and a local register of historic places support these preservation efforts (City of Fredericton n.d. b).

Saint John, one of Canada’s oldest cities, is distinguished by its Victorian aesthetic, a result of the red brick reconstruction following the Great Fire of 1877 (Goss 2009: 200). Several heritage conservation districts, governed by the Heritage Areas By-law and concentrated in the downtown core, ensure the preservation of this iconic architecture (City of Saint John n.d. a). The Heritage Development Board provides financial incentives such as grants and tax benefits to support restoration projects (City of Saint John n.d. b).

2.1.3 Challenges in heritage preservation

While heritage regulations are intended to protect historic buildings, they sometimes lead to unintended consequences such as demolition by neglect (Mann 2022; Webb 2019). Due to insufficient financial resources or lack of viable uses, many heritage buildings remain vacant and abandoned, accelerating their deterioration. Over time, their condition becomes so critical that they are deemed irreparable and legally demolished. For example, the demolition in 2019 of the Centenary Queen Square Church in Saint John highlighted how a lack of investment can result in the loss of an important heritage property (Webb 2019).

This issue reflects a broader tension between heritage preservation and the pressures of socio-economic development (Hoang 2021; Lordkipanidze et al. 2005). In modern profit-driven economies, the economic value of real estate often takes precedence over heritage concerns. As Harvey (1985) and Krätke (2014) argue, the treatment of urban real estate as a financial asset drives strategies to maximise land value, often at the expense of existing structures and vulnerable communities. The growing demand for housing and urban expansion further exacerbates the destruction of historic buildings, which are frequently replaced with more profitable developments such as apartment blocks and commercial complexes. Heritage properties face additional challenges, including high renovation costs, difficulties in sourcing specialised materials, a lack of expertise, and the complexity of adapting these structures to modern standards (Pintossi et al. 2021; ICOMOS 2005). These factors make historic buildings less appealing to investors, leading to prolonged neglect that justifies their eventual demolition for economic gain.

Given these pressures, regulatory protection alone is insufficient. Proactive and practical strategies are needed to safeguard these buildings before they become irreparably vulnerable. One promising solution is adaptive reuse, which balances heritage preservation with contemporary needs and economic viability.

2.2 Adaptive reuse as a strategy for preservation

Adaptive reuse is the process of repurposing existing buildings or structures for uses other than what they were originally designed for, while retaining their historic or architectural elements. By giving new uses to ageing structures, adaptive reuse combines elements from heritage preservation with contemporary needs, ensuring their continued relevance in modern urban landscapes (Bullen & Love 2011). Unlike traditional preservation efforts, which focus on maintaining or recreating a building’s historical state, adaptive reuse adapts to meet present-day requirements and demand without erasing their historical value. While preserving heritage values, adaptive reuse also offers a comprehensive solution to some of the environmental and social challenges of the construction and renovation industry.

2.2.1 Environmental benefits

As environmental concerns continue to grow within the building and construction sectors, adaptive reuse emerges as a sustainable alternative to demolition and new construction, addressing critical environmental challenges. The construction industry accounts for 30% of global energy use, 26% of energy-related CO2 emissions and produces significant amounts of waste from material production processes of, for example, cement and steel (IEA 2022). In Canada, buildings are responsible for 13% of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions, highlighting the need for innovative solutions to mitigate these impacts (Environment and Climate Change Canada 2023).

Adaptive reuse offers a practical solution to mitigate these impacts by extending the life of existing structures and reducing the demand for new construction materials. The key environmental benefits of adaptive reuse include the following:

Reducing resource demand

By extending the life-cycle of buildings, adaptive reuse minimises the extraction of raw materials and reduces habitat destruction, deforestation and related carbon emissions (Ahmed Ali et al. 2020).

Minimising waste

Diverting demolition waste from landfills alleviates one of the largest environmental burdens in the construction sector (Bullen & Love 2011).

Preserving embodied energy

Adaptive reuse retains the energy embedded in the original construction materials and reduces the carbon footprint associated with material production and transportation (Foster 2020; Baker et al. 2021).

Improving energy efficiency

Through retrofitting, adaptive reuse enhances energy performance in older buildings, integrating efficient systems that lower long-term energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions (Mohamed et al. 2017).

2.2.2 Social and cultural benefits

Adaptive reuse of historic buildings is an effective strategy for preserving heritage value while generating significant social and cultural benefits by connecting present generations with the past. By extending the life-cycle of historic structures, it safeguards their value and creates new cultural and social opportunities (Ben Ghida 2024; Bullen & Love 2011; Mowry 2024). These benefits include the following:

Enhancing cultural identity

Preserving historic buildings maintains local history, strengthens cultural roots and fosters collective pride (Othman & Elsaay 2018).

Strengthening social cohesion

Transforming abandoned buildings into public spaces encourages social interaction, intergenerational dialogue and intercultural exchange (Niemczewska 2020).

Promoting culture and the arts

Repurposing buildings as museums, libraries or art centres revitalises cultural life and meets modern social needs (Niemczewska 2020).

Revitalising neighbourhoods

These projects rehabilitate neglected areas, attract economic activities and respect historical significance (Bullen & Love 2011; Othman & Elsaay 2018).

Preserving knowledge and memory

Highlighting traditional skills and cultural histories sustains collective memory in a contemporary context (Niemczewska 2020).

2.2.3 Challenges and barriers to adaptive reuse

Adaptive reuse of historic buildings is a complex process that involves cultural, technical, regulatory and economic challenges, many of which overlap with traditional heritage preservation but also present unique obstacles. Addressing these difficulties requires tailored approaches, which will be explored in detail in the present research.

At the cultural level, local resistance often stems from fears of losing authenticity or heritage devaluation, while poorly planned projects may lead to gentrification that displaces local communities (Conejos et al. 2016; Pintossi et al. 2021).

Technically, renovations face challenges such as addressing structural and thermal issues, integrating modern standards such as energy efficiency and accessibility, and preserving heritage value (Plevoets & Sowińska-Heim 2018). Smaller municipalities often lack the specialised expertise needed for such projects (Bullen & Love 2011).

Regulatory constraints, including heritage zone restrictions and difficulties reconciling modern codes with older building characteristics, add further complications (Pintossi et al. 2021).

Finally, economic challenges—such as high initial costs, limited funding mechanisms and economic pressures—frequently hinder project feasibility (Shipley et al. 2006).

2.3 The case for adaptive reuse in New Brunswick

Despite these obstacles, Canadian examples show that adaptive reuse can offer viable solutions that address contemporary needs while preserving heritage value. Projects such as Toronto’s Distillery District and Winnipeg’s Forks Market highlight its ability to combine cultural conservation with urban renewal (Kovacs et al. 2015). The Distillery District, once a 19th-century industrial distillery, has been transformed into a vibrant neighborhood with restored historic buildings housing art galleries, shops and event spaces, preserving its heritage character while meeting modern urban needs. Similarly, Forks Market, repurposed from former rail warehouses, now serves as a lively community hub with cultural, commercial and recreational spaces that respect the site’s architectural legacy. These examples demonstrate how adaptive reuse can extend the life of historic buildings while creating dynamic, integrated spaces that balance heritage preservation with urban revitalisation.

However, challenges persist, particularly financial, technical and regulatory barriers. Wiebe (2021) notes that many developers view adaptive reuse as unviable due to high upfront costs, difficulties modernising historic structures to meet building codes and navigating complex heritage regulations (Wiebe 2021). Pintossi et al. (2021) further highlight these obstacles, particularly in smaller cities where limited resources and expertise make adaptive reuse projects more difficult to execute. The present paper will thus aim to answer the following research question: How are derelict heritage buildings at risk of demolition preserved through adaptive reuse in urban settings in New Brunswick?

3. Methods

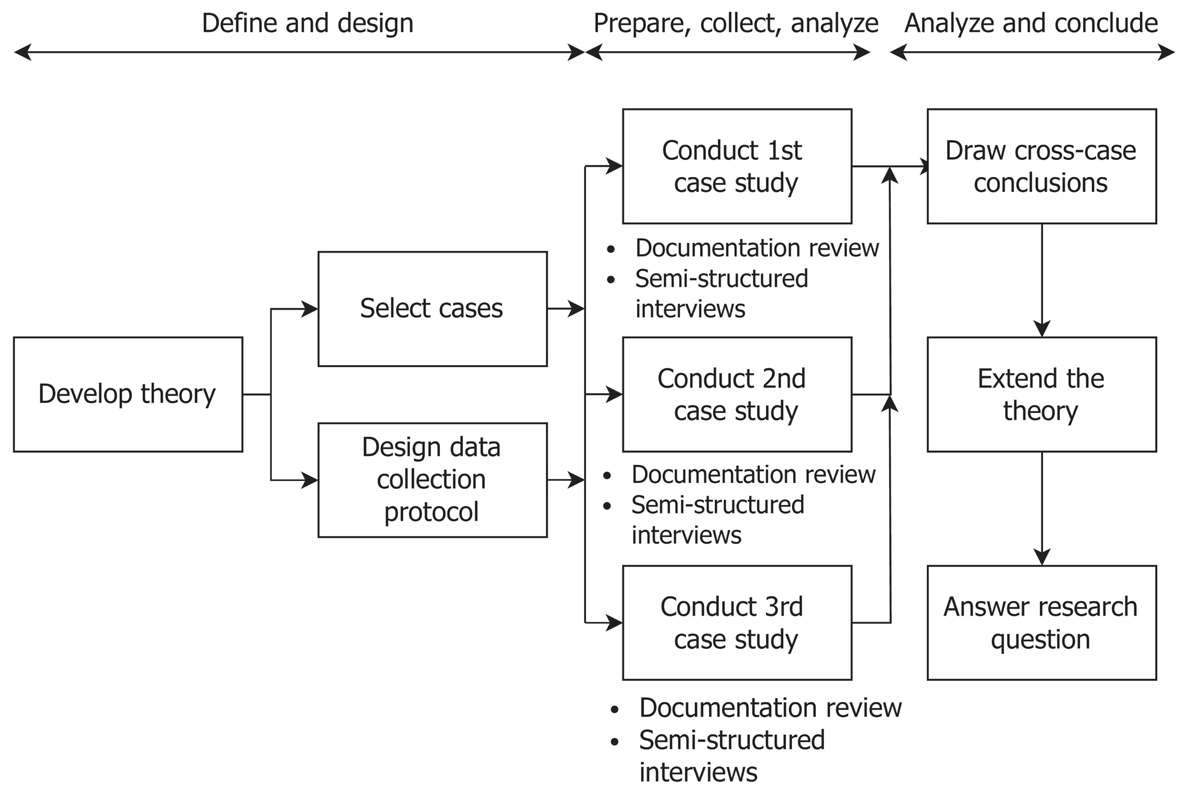

This paper examines how derelict buildings at risk of demolition are successfully preserved through adaptive reuse in New Brunswick. The study employs a qualitative, inductive approach using a multiple-case study design, as described by Yin (2009), to investigate multiple projects in real-world contexts. This method enables an in-depth exploration of the factors, strategies and challenges involved in adaptive reuse, particularly those that are subjective and not easily quantifiable. By focusing on qualitative analysis, the research reveals key relationships, themes and processes that contribute to the success of adaptive reuse initiatives, providing a nuanced understanding of their implementation (Yin 2009). Figure 1 shows the analytical process used in order to examine the different cases.

Figure 1

Multiple-case study design.

Source: Adapted from Yin (2009).

3.1 Case selection criteria

A case for each of the primary urban centres of New Brunswick—Moncton, Fredericton and Saint John—is examined. The cases are identified from Parks Canada’s Historic Places database (Parks Canada n.d.) and preliminary discussions with municipal representatives of the three selected urban centres. Selection is done purposively based on the following criteria: (1) urban location (Moncton, Fredericton or Saint John); (2) adaptive reuse of a non-residential historic building; (3) access to relevant information; (4) inclusion of social and environmental aspects in adaptive reuse; and (5) the availability of project stakeholders for interviews. For lists of cases that were considered for each city, see Appendix A in the supplemental data online.

3.2 Design and data collection protocol

3.2.1 Documentation review

The documentation review involves systematically gathering and evaluating a variety of publicly available sources, including archives, media coverage, government documents and technical reports. Each source is classified by document type and organised thematically: (1) to confirm that each selected case meets the established criteria; (2) to provide context for the case study; and (3) to identify trends or key themes that could help answer the research question—specifically, understanding the factors that contribute to the success and feasibility of these cases. This method allows for a comprehensive analysis of the distinct characteristics of each studied project, such as construction year, building functions, renovation timelines and methods, and specific approaches to adaptive reuse.

3.2.2 Thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews

A semi-structured interview guide featuring open-ended questions was employed to prompt reflection and facilitate sharing experiences among respondents for each stage of the adaptive reuse project (see Appendix B in the supplemental data online). Eight interviews were carried out with 13 stakeholders engaged in adaptive reuse projects, including building owners (BO), municipal government officers (M) and project architects (A). Both individual and small-group formats were used based on the most effective approach for gathering information from each participant category.

Thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke 2006) was used to analyse the transcripts of the semi-structured interviews to identify the conditions for a successful adaptive reuse at each stage. This approach systematically identifies, categorises and discusses themes within a qualitative dataset, which may include interview transcripts or diverse types of documents. Subsequently, these transcripts were inductively coded to highlight the different aspects contributing to each case’s successful completion for each stage of the project, as viewed from the perspectives of building owners, architects and municipal officers.

4. Results

The results of the multiple-case study are presented below. Each case is informed by two primary data sources: a detailed document review and insights from semi-structured interviews. The analysis begins with an individual examination of each case to provide context and highlight its unique dynamics. This is followed by a comparative analysis of the semi-structured interview data to identify common trends and overarching themes across the cases. Documentation review was used to describe each case as well as to inform comparative analysis; for a quantitative summary of documents reviewed, see Appendix C in the supplemental data online. This structured approach ensured a comprehensive understanding of the key factors influencing the outcomes of each adaptive reuse project.

4.1 Overview of the case studies

Preliminary research identified nine adaptive reuse projects in Moncton, seven in Fredericton and 18 in Saint John (see Appendix A in the supplemental data online). The final selection of cases was guided by two key criteria: the availability of stakeholders for interviews; and the accessibility of relevant documentation and information. As a result, one case was chosen from each city: Moncton, Fredericton and Saint John. Table 1 provides an overview of the selected cases.

Table 1

Summaries of the three case studies in New Brunswick, Canada.

| CASE STUDY 1: MONCTON | CASE STUDY 2: FREDERICTON | CASE STUDY 3: SAINT JOHN | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Company/organisation | Botsford Station Creative Commons | Picaroons Brewing | Saint John Theatre Company |

| Building(s) | Botsford Station | Former Gibson Roundhouse | Motor car and equipment garageSydney Street Courthouse |

| Street(s) | Botsford Street | Union Street | Princess StreetSydney Street |

| Construction year(s) | 1913 | 1885 | 19111829 |

| Original use(s) | Manufacturing | Railway roundhouse | Automobile garageCourthouse |

| Renovation year/period | 2011–current | 2015 | 20112019–current |

| Current use | Retail and offices | Brewery | Theatre studio |

| Status(es) | Continuous renovation while occupied | Renovated and occupied | Renovated and occupiedPlanning stage |

The findings for each case are presented below, beginning with a detailed exploration of each case to provide context, followed by a comparative analysis to identify shared themes and trends across the cases.

4.2 Individual case report

4.2.1 Case study 1: Botsford Station Creative Commons, Moncton

Constructed in 1913, Botsford Station began as a clothing manufacturing plant specialising in hats and caps. Its location on Botsford Street was chosen for proximity to Moncton’s fossil gas line, powering many nearby industrial buildings (Common Council of the City of Moncton, NB 1915). The project relocated 60–65 families from Truro, where the company originated. After closing (date unknown), the brick building fell into disrepair, with vinyl siding, boarded windows and use as storage until its acquisition in 2011.

The building has since undergone adaptive reuse. The ground floor now hosts retail space, and the upper floors serve as community incubators and offices. Initially, the Botsford Creative Commons was formed as a volunteer-driven non-profit (2012–14) to transform the space as a hub for people and ideas.

Renovation efforts, phased floor by floor since 2011, include ecofriendly practices:

Brownfield clean-up (removal of an oil tank).

Installation of double-pane aluminium windows and salvaged doors.

A new roof with R60 cellulose insulation.

A variable refrigerant flow (VRF) heating system.

Recycled furnishings discarded by local restaurants and hotels.

Despite being structurally sound, challenges included improving accessibility, meeting fire codes and addressing porous brick walls without compromising insulation. The total renovation cost is estimated at CAD1 million.

4.2.2. Case study 2: Picaroons, former Gibson Roundhouse, Fredericton

Constructed in 1885, the former Gibson Roundhouse originally served as a railway maintenance facility for the Northern and Western Railway, built with 500,000 locally sourced bricks from Boss Gibson’s brickyard. After its railway use ended, it became an automotive repair shop before being abandoned for years. Recognised as a historic site in 2008, the City of Fredericton sold the property to Northampton Brewing (Picaroons Traditional Ales) in 2013 for CAD100, under an agreement to transform it into a brewery and community hub, revitalising the area around Carleton Park.

The adaptive reuse retained the original roundhouse structure with modern extensions added to support its new functions. The facility now houses a brewery, meeting rooms, a historic interpretation centre, and public amenities such as parking, washrooms and event spaces. To address its flood-prone location near the Saint John River, the building was designed to accept and release floodwaters with minimal damage.

Key efforts included the following:

Brownfield clean-up and site restoration.

Retrofitting for brewing operations while preserving historic character.

Adding modern extensions and sustainable features such as energy-efficient systems and repurposed materials.

Creating community spaces, including a beer garden, public trail access and event areas.

Completed in December 2016 at a cost of CAD7 million, the project overcame challenges such as flood management and compliance with modern codes while maintaining its heritage. The site now generates CAD85,000–120,000 annually in property taxes.

4.2.3 Case study 3: Saint John Theatre Company, motor car and equipment garage, and Sydney Street Courthouse, Saint John

The Saint John Theatre Company has successfully implemented adaptive reuse through projects such as the transformation of the BMO Studio Theatre at 112 Princess Street. Once a neglected heritage building, it was rehabilitated into a functional arts venue while retaining its historic character. The CAD2 million project balances heritage preservation with modern functionality and now serves as a vital space for performances, workshops and events, supporting the local arts community and fostering public engagement.

Building on this success, the theatre company is now redeveloping the Sydney Street Courthouse, a National Historic Site constructed 1826–29. Surviving both the Great Fire of 1877 and a fire in 1919, the building remained vacant after the law courts relocated in 2013. Acquired in 2020, the CAD17.9 million project aims to transform the courthouse into a state-of-the-art performance and event space while preserving its architectural integrity.

Key upgrades included the following:

Renovating the courthouse to maintain its historic fabric.

Constructing a three-storey infill structure for enhanced usability.

Modernising the facility for multipurpose events and performances.

Integrating adaptable design features to meet contemporary safety standards.

Once completed, the Sydney Street Courthouse will serve as a cultural hub, revitalising Saint John’s historic district, supporting arts and theatre in the region.

4.3 Cross-case comparison

The semi-structured interviews revealed key themes across projects contributing to the success of adaptive reuse projects in New Brunswick. These themes include collaboration among stakeholders, financial strategies, technical expertise, community engagement, and the condition and regulatory requirements of heritage buildings.

4.3.1 Vision, commitment and leadership

The success of adaptive reuse projects begins with the vision and commitment of building owners, who often prioritise cultural preservation and social impact over immediate financial returns. Their leadership drives creative transformations, such as theatres, community hubs and workspaces, that serve contemporary needs.

If the space needs to be saved and it’s an awesome space, that’s enough. Marry it with a vision and develop it knowing the value it generates will far exceed the cost to save it.

(BO-1)

Municipalities demonstrate leadership by acquiring at-risk buildings, identifying preservation-minded buyers and providing early guidance to navigate project challenges.

The complexity is that the building wasn’t just an ordinary building, it was heritage. So, it was very tricky finding the right buyer for that and knowing they wouldn’t just demolish it.

(M-3)

4.3.2 Financial management and funding strategies

Restoration costs remain a significant challenge due to hazardous materials, the need for specialised expertise and sustainability goals. Strategies such as value engineering, phased renovation and material reuse help mitigate financial burdens.

We didn’t have money for the elevator, so we left the elevator shaft as a hole in the wall for the first few years.

(BO-2)

Mixed funding sources—including government grants, tax credits, private investments and community contributions—are critical, though often inconsistent. Long-term financial and non-financial returns, such as increased property values, tourism and cultural preservation, further justify investments in adaptive reuse.

The location is unique. From a tourism point of view, we’ve had far greater impact than a rectangular building in an industrial park would have achieved.

(BO-4)

4.3.3 Technical considerations and building conditions

The condition of heritage buildings introduces specific challenges, including the presence of hazardous materials and health and safety priorities. Addressing these issues requires specialised protocols and expertise to ensure compliance with health standards and regulatory frameworks.

Municipalities and regulatory bodies play a key role by offering flexibility in the application of building codes and adapting regulations for heritage projects. Government support for architects, combined with tailored codes and municipal adaptability, allows adaptive reuse projects to meet safety requirements while respecting historic integrity.

Inspectors are often more flexible with heritage buildings, allowing natural ventilation to account for modern engineering systems.

(A-1)

4.3.4 Expertise and collaboration

The success of adaptive reuse projects relies heavily on engaging experts early in the process, including architects, engineers and heritage professionals. This collaboration ensures better planning, addresses challenges such as structural integrity and hazardous materials, and facilitates smooth project execution. However, expertise in heritage preservation remains limited in New Brunswick, requiring ongoing collaboration with municipal heritage services and specialists.

We hired experts because we admitted we didn’t know what we were doing, and that made all the difference.

(BO-2)

Participatory renovation efforts further address expertise and cost challenges by involving the community in tasks such as cleaning, painting and minor repairs. This approach not only reduces costs but also builds a sense of ownership and pride in the project.

We provided an opportunity for people to get involved in a way that allowed them to be themselves and feel a sense of purpose and meaning.

(BO-1)

4.3.5 Community engagement and support

Community involvement emerged as a critical theme in adaptive reuse success. Grassroots advocacy often initiates adaptive reuse efforts, drawing attention to underutilised properties and rallying support from municipalities and developers. Involving the community throughout the planning and design phases ensures that projects align with local needs, enhancing neighborhood vibrancy and fostering long-term sustainability.

We had a vision that was exciting for people to rally behind—a purpose and place they could belong to.

(BO-1)

4.3.6 Strategic building selection

Successful adaptive reuse projects prioritise heritage buildings with strong structural integrity and significant historical or architectural value. Robust older buildings are particularly well-suited for reuse, as their quality is costly to replicate today. Poorly constructed buildings, especially from the mid-20th century, are often unsuitable for adaptive reuse due to structural and financial limitations.

The robustness of older buildings cannot be replicated today without spending millions, making them ideal candidates for reuse.

(A-3)

5. Discussion

The adaptive reuse cases studied share several common characteristics contributing to their success. The primary finding from the interview analysis is that success in adaptive reuse projects requires stakeholders to adopt an alternative approach—one that diverges from conventional real estate models by prioritising physical and contextual factors over profitability. As Harvey (2003) and Krätke (2014) suggest, the commodification of urban spaces, particularly buildings, often has significant consequences for existing structures and vulnerable communities, and historic buildings are no exception to this trend. This underscores the importance of shifting focus beyond profitability to ensure the long-term success and sustainability of adaptive reuse projects. In all cases, municipal officers, architects and other stakeholders collaborated early in the project process to align their vision with that of the building owners. This alignment improved coordination, streamlined decision-making and introduced innovative strategies that contributed to project success. Adaptive reuse projects further benefit from collaborative governance to align stakeholders, phased financial strategies to manage risk and the early involvement of technical expertise to address structural challenges. Active community engagement also plays a critical role by securing public support and ensuring the projects reflect local needs.

This paradigm shift departs from established construction and renovation norms, enabling adaptive reuse projects to succeed where profitability-based practices often fail. These projects demonstrate not only how adaptive reuse can be implemented effectively but also how the construction and renovation industry can embrace innovative methodologies to promote sustainability. As Bullen & Love (2011) argue, building conservation has evolved from simple preservation to a fundamental component of urban regeneration and broader sustainability strategies. The adoption of adaptive reuse as a tool for sustainable development requires rethinking traditional approaches to building management, design and finance. Unlike conventional practices that prioritise demolition and new construction, adaptive reuse integrates existing structures into contemporary use while minimising resource consumption and waste generation. This approach aligns with environmental goals such as reducing embodied carbon emissions, conserving energy and preserving cultural heritage.

The following sections discuss the techniques, governance frameworks and technical expertise that enabled the success of these projects. By analysing these elements, this research highlights practical strategies that can be applied to future adaptive reuse initiatives, emphasising their role in achieving sustainable urban regeneration.

5.1 Collaborative frameworks for adaptive reuse success

The success of adaptive reuse projects relies on a shared vision and coordinated efforts among stakeholders, including municipalities, community advocates, building owners and technical experts. Municipalities often acquire derelict historic buildings to prevent their deterioration and identify suitable owners who can repurpose them effectively. By prioritising owners with specific and well-defined, building-specific visions—such as a brewery, studio theatre or community incubator—municipalities enable projects that align with community needs rather than profit-driven objectives, such as maximising rental income. Case studies demonstrate the importance of matching vision with functionality. For example:

Repurposing a building as a brewery utilised its industrial layout and structural capacity to accommodate brewing equipment and operations. Additionally, its location within a park and proximity to bike trails facilitated customer access and contributed to its commercial success.

Transforming a courthouse into a studio theatre allows leveraging the building’s existing features, such as marble floors, architectural columns and favourable acoustics. Interior spaces, including the old courtroom, were adapted for performance use, while the building’s prime downtown Saint John location enhanced its accessibility and cultural value.

Establishing a community incubator capitalised on the building’s central location in downtown Moncton, providing proximity to businesses and fostering opportunities for collaboration and innovation within the local economic ecosystem.

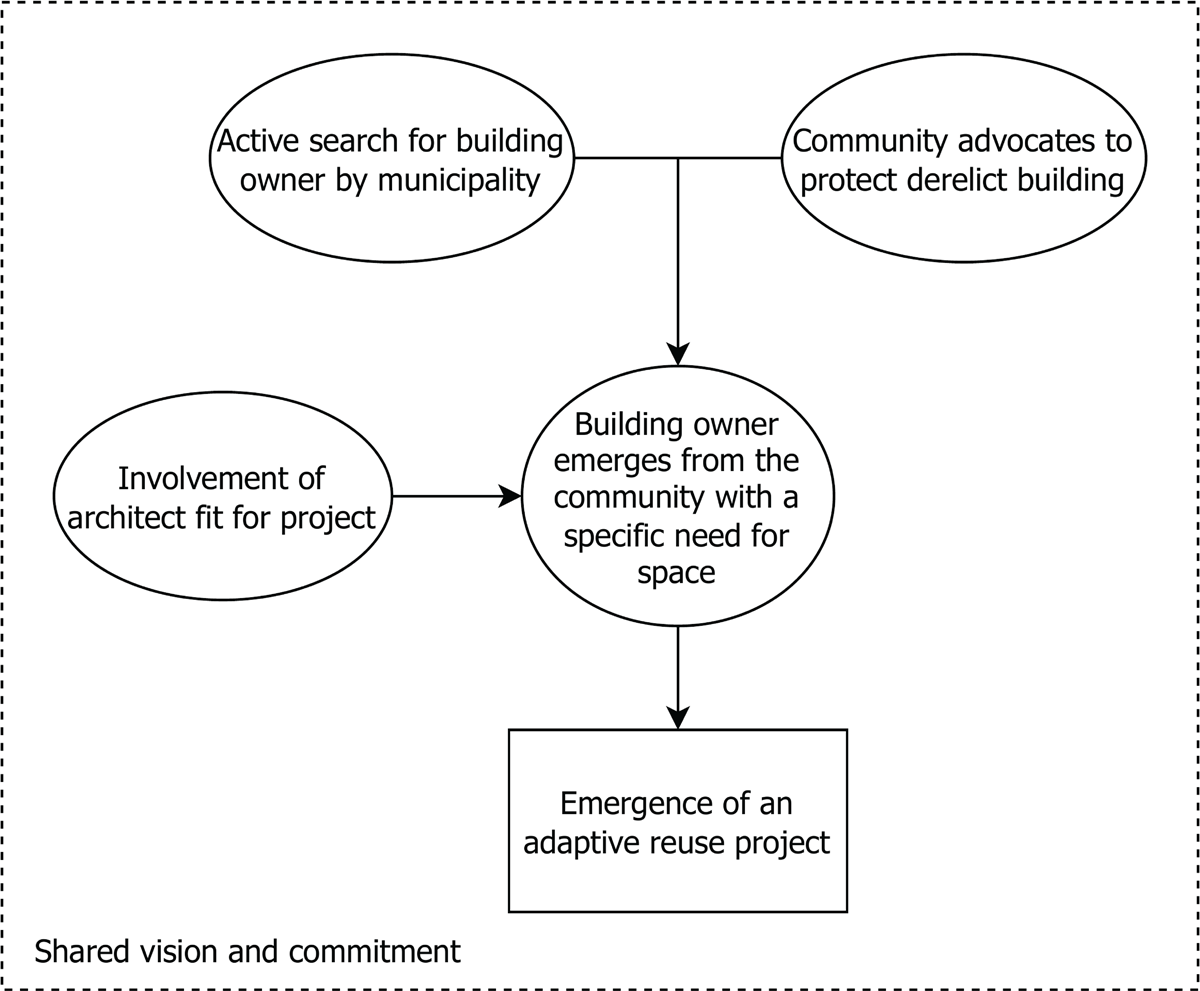

Figure 2 illustrates the interconnected roles of stakeholders, which were present in all three cases. Municipalities initiate the process by identifying buildings and potential owners, while community advocates work to protect underutilised structures and generate public support. The building owner, often rooted in the community, approaches the project with a clear functional need that determines the building’s future use. This alignment between the owner’s vision and the physical attribute of the structure is central to project feasibility and success. Architects contribute significantly during this process by addressing preservation requirements while integrating contemporary functionality. Their early involvement ensures that structural adaptations, safety standards and accessibility needs are considered alongside heritage preservation. This technical expertise enables the alignment of the building’s physical characteristics with its intended purpose, minimising delays and ensuring compliance with regulatory standards.

Figure 2

Stakeholder collaboration in the emergence of adaptive reuse projects.

The collaborative framework enables public, private and community stakeholders to collectively address regulatory, financial and technical challenges, ensuring the success of adaptive reuse projects. As Plevoets & Sowińska-Heim (2018) highlighted, such collaboration fosters consensus, minimises conflicts and enhances project outcomes. Municipalities play a key role by streamlining regulatory processes, facilitating approvals and ensuring compliance with preservation standards. Community stakeholders provide essential advocacy and local support, while architects contribute technical expertise to balance preservation requirements with modern functional needs. By aligning a building’s physical attributes with a clearly defined vision and fostering collaboration across stakeholders, adaptive reuse projects achieve practical, sustainable outcomes that preserve historic value while meeting contemporary needs.

5.2 Strategic and financial planning as the foundation of adaptive reuse success

The planning phase is fundamental to the success of adaptive reuse projects, as it translates shared visions into actionable strategies. This phase involves addressing challenges related to financial management, technical considerations, regulatory compliance and stakeholder collaboration.

Addressing the financial complexities of adaptive reuse requires a diversified approach that combines public funding, private investment and community participation. Public funding remains a cornerstone for heritage preservation through federal, provincial and municipal programmes, including grants, tax incentives and conservation initiatives. These mechanisms reduce the financial burden associated with adaptive reuse projects and incentivise their implementation.

Private funding, sourced from businesses, individuals and organisations, supplements public financing. While private investments may not generate immediate financial returns, they align with broader cultural and economic objectives, such as long-term community revitalisation. Community participation further complements public and private efforts through initiatives such as fundraising and volunteer contributions, fostering shared ownership and accountability in the preservation process.

To manage costs effectively, financial strategies such as value engineering, phased construction and material reuse are commonly applied. Value engineering ensures cost-efficient solutions without compromising project objectives, while phased construction distributes expenses over an extended period, alleviating short-term financial pressures. Material reuse reduces expenditures by repurposing original building components, contributing to both economic and environmental sustainability.

Long-term financial and non-financial benefits—such as increased property values, tourism growth and cultural preservation—often justify the significant investment required for adaptive reuse projects.

5.3 Technical expertise, building conditions and strategic selection

Technical considerations play a critical role during the planning phase, particularly in evaluating the physical condition of heritage buildings. Common challenges include structural degradation, outdated systems and the presence of hazardous materials such as asbestos. Effective management of these challenges requires specialised expertise to ensure compliance with safety regulations and health standards. Early technical assessments are essential to identifying potential risks, reducing delays and minimising unforeseen costs.

Strategic building selection is a key component of technical planning. Heritage buildings with strong structural integrity and significant architectural or historical value are prioritised, as they offer a solid foundation for reuse and reduce the complexity of renovations. These older structures, often built with superior materials and craftsmanship, are costly to replicate today and provide unique opportunities for adaptive reuse. In contrast, buildings constructed with lower quality materials, particularly those from the mid-20th century, may lack the durability and adaptability required for reuse, making them less viable candidates.

Architects, engineers and heritage professionals are central to integrating preservation requirements with modern functionality. Their expertise ensures that structural modifications, accessibility upgrades and safety standards are implemented effectively while maintaining the building’s historical integrity (Arfa et al. 2024). Modern systems such as ventilation and utilities can often be integrated through flexible regulatory applications tailored for heritage projects. Municipal involvement is equally critical, as regulatory bodies provide guidance and adapt building codes to address the unique constraints of heritage structures.

In regions with limited local expertise, collaboration with professionals from other jurisdictions is often necessary. This is particularly relevant in smaller provinces, where specialised skills in heritage conservation and structural restoration may be scarce. Such partnerships ensure that projects benefit from the required technical knowledge and resources to achieve successful outcomes.

5.4 Key elements and stakeholder roles in adaptive reuse projects

The success of adaptive reuse projects hinges on the collaborative efforts of key stakeholders—architects, building owners and municipal representatives—each fulfilling distinct roles to address technical, financial and governance challenges. This section identifies the critical elements and responsibilities that emerged from the study, illustrating the strategies and approaches adopted to ensure the effective delivery of adaptive reuse projects.

Table 2 highlights the roles of stakeholders and strategies necessary to overcome challenges encountered throughout the adaptive reuse process. These findings reinforce the existing literature, as they highlight the significance of shared values, technical expertise and stakeholder collaboration as essential components for enhancing project feasibility, ensuring regulatory compliance and promoting long-term sustainability.

Table 2

Roles and strategies to overcome challenges to adaptive reuse.

| ROLE | KEY ELEMENT | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|---|

| Architect | In-depth building inspection | Conduct thorough assessments to understand the level of renovation required |

| Architect, owner, municipality | Shared values and commitments | All stakeholders sharing common values and a unified goal |

| Architect, owner, municipality | Community involvement and collaborative governance | Implement an equal-level decision-making process and involve the community in the planning and design phase |

| Architect, owner, municipality | Understanding codes, regulations and involving government agencies | Navigate regulatory processes, obtain necessary approvals and ensure compliance with regulatory requirements |

| Architect, owner, municipality | Plan for phased construction | Extend the project timeline for gradual implementation to manage resources efficiently |

| Architect, owner, municipality | Use participatory renovation | Integrate local perspectives and promote collective ownership of historical preservation and redevelopment efforts |

| Owner | Vision and specific spatial needs | Develop a clear vision to fulfil a specific purpose for the building’s intended use |

| Owner | Obtain diversified financing | Use various funding sources |

| Owner, architect | Engage heritage experts | Preserve historical integrity and ensure compliance with heritage preservation guidelines |

| Owner, architect | Use-value engineering | Strategically prioritise renovation components to optimise profitability and reduce project costs |

| Owner, architect | Effective management of hazardous materials | Ensure healthy and sustainable renovation of existing buildings |

| Owner, architect | Reuse building materials and furniture | Promote sustainability by reducing waste and optimising resource use |

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the success of adaptive reuse projects lies in the collaborative, innovative and strategic approaches adopted by key stakeholders, including architects, building owners, municipal representatives and the broader community. The findings highlight the need for a shift from conventional real estate models—driven by profitability—to strategies that prioritise physical and contextual factors, such as location, structural adaptability and cultural value.

A central theme emerging from the analysis is the importance of shared vision and alignment among stakeholders. Collaborative frameworks that integrate public, private and community participation are essential for fostering cohesive decision-making, minimising conflicts and ensuring project feasibility. These collaborative efforts not only preserve the cultural and historical integrity of derelict structures but also enhance their role in urban regeneration and sustainability.

The research further underscores the importance of strategic planning as the cornerstone of adaptive reuse success. A multifaceted approach to financing, including phased construction, community support and value engineering, enables the efficient allocation of resources while overcoming economic challenges. Additionally, the early involvement of architects and heritage experts ensures that preservation imperatives are balanced with contemporary functionality, contributing to the adaptive reuse of buildings as vibrant, functional spaces.

Finally, the findings emphasise the role of expertise and governance in addressing technical and regulatory challenges during the renovation process. Effective management of hazardous materials, adherence to heritage by-laws and the reuse of materials reflect an industry shift toward sustainability. However, the scarcity of specialised expertise in smaller regions, such as New Brunswick, highlights the need for cross-regional collaboration to ensure the successful implementation of adaptive reuse projects.

By illustrating practical strategies and interconnected stakeholder roles, this study reinforces the evolving role of building conservation as a key component of urban resilience and sustainability. Adaptive reuse projects offer a tangible demonstration of how innovative methodologies, collaborative governance and shared commitments can transform derelict structures into valuable community assets. Moving forward, these insights contribute to the broader discourse on sustainable urban development, providing a framework for future adaptive reuse initiatives.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Data accessibility

The data used for this study are confidential and are not shared publicly.

Ethical approval

This research was approved by Université de Moncton’s Ethics Review Board (file number 2223-026).

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at: https://doi.org/10.5334/bc.495.s1