1. Introduction

The European Union is striving for Europe to become the ‘first climate-neutral continent’ by 2050 (European Union 2019). Globally, the building sector accounts for over one-third of all carbon emissions (UNEP 2022). Recent research shows that without lifestyle changes, the 1.5°C global warming target will not be achievable in the European Union (Cap et al. 2024). Thus, consumption sufficiency is required in addition to production efficiency. Building as an industrial sector and housing as a consumption domain play important roles here. As the carbon intensity of energy production is decreasing, the relevance of the buildings is growing (Röck et al. 2020), also from a sufficiency perspective (Bierwirth & Thomas 2019). The circular economy offers various solutions to curbing emissions and other environmental effects in the building sector (Ruokamo et al. 2023). Sharing economy practices in particular have under-utilised potential to increase sufficiency in housing.

Mi & Coffman (2019) see that consumers play a critical role in enabling the sustainability benefits of sharing because they are the most essential participants in the sharing economy as both owners and users of shared products and services. Space and storage represent one potential shareable resource and, according to Rathnayake et al. (2024), they are among the most studied shareable resource categories. On the other hand, these studies focus on the accommodation industry, hospitality sector and coworking spaces, whereas private homes and spaces have been studied more rarely. There is also accumulating literature on potential factors that influence the adoption of sharing practices. A literature review by Rathnayake et al. (2024) suggests that social, cultural and behavioural factors, along with regulatory and product and service factors, affect the implementation of sharing-economy practices. However, the role of these aspects is not well understood in the context of private housing and citizens. In addition, methodologically, previous research has only rarely used large-scale quantitative approaches (as an exception, see Boyer & Leland 2018 from the US context). Furthermore, recent research on housing sufficiency (e.g. Lehner et al. 2024) notes the need to understand better to what degree increasing urbanisation and previous experiences of sharing may affect citizens’ willingness to share spaces. Hence, merit exists in investigating citizen perspectives of space-sharing.

This study aims to fill the abovementioned gaps by providing insights from a nationwide survey conducted in Finland in 2022. It focuses on three research questions:

RQ1: What kind of citizen perceptions on sharing spaces can be identified from Finland?

RQ2: How do citizens reflect on these in terms of their personal housing experiences and perceptions, and what kind of resistance types and improvement suggestions to mainstream space-sharing practices occur?

RQ3: Using regression analysis, how do socio-economic and other factors influence the propensity to share spaces at the population level?

This study addresses RQ1 and RQ2 using both quantitative and qualitative data, along with open-ended responses from the nationwide survey.

The paper is organised as follows. Section 2 introduces the background and relevant literature. Section 3 presents the empirical setting and data. Section 4 gives the results. Section 5 discusses the results and concludes.

2. Background and literature

2.1 Sufficiency and space-sharing

Sufficiency in housing is related to both social and environmental sustainability. Minimum standards for decent or sufficient living should be met, while resource use and its environmental impacts should not overshoot (Lettenmeier et al. 2012). Overall, housing contributes greatly to the carbon footprints of lifestyles and has potential for reducing carbon emissions (Koide et al. 2021; Ivanova et al. 2020). On the other hand, the carbon intensity of the energy used for housing has been decreasing in many countries (Scarlat et al. 2022), in turn increasing the relevance of material and space choices, along with maintenance aspects, in the climate impacts of housing (Ruokamo et al. 2024; Röck et al. 2020; Walesiak & Dehnel 2024). A smaller amount of living space per household member could be an approach to decreasing these impacts (Daly 2017; Koide et al. 2021; Malmqvist & Brismark 2023), but earlier development rather points in the opposite direction (Bierwirth & Thomas 2019).

Two housing sufficiency strategies are distinguished in the literature to address housing size: a reduction in household private living space and the shared use of living space across households (Lehner et al. 2024). In practical terms, the housing sufficiency component could also be associated with decreasing energy use, contributing to lower lifestyle carbon footprints (Lettenmeier et al. 2014; Nyfors et al. 2020; Sandberg 2021). With current new residential houses characterised by high energy efficiency, living space sufficiency aspects require more attention, especially as existing incentives, such as building regulations and status symbols, tend to increase floor space (Francart et al. 2020; Fuchs et al. 2021; Huber 2022). Space-sharing could be a way of decreasing living space while maintaining or even increasing comfort (Francart et al. 2020).

As the sufficiency approach relies heavily on individual choices, consumer perception and acceptance are crucial for its development. Some scholars have addressed this and studied the targets for and obstacles to decreasing floor space (Fuchs et al. 2021; Sandberg 2018). Based on qualitative data from workshops in five European countries, Lehner et al. (2024) found that participants evaluated shared living mainly negatively, and only one in five voiced acceptance for the low-carbon lifestyle option ‘I will choose shared housing’. They further reported that the perception of sufficiently large housing is rather driven by a relative comparison with the immediate environment than by objective measurements such as floor area (m2) per person.

2.2 Relevant aspects of space-sharing

Behaviour-related options for lifestyle change are not very popular among households (Vadovics et al. 2024), and sharing space can thus face various obstacles (Hagbert 2016). On the other hand, it can become attractive and have positive effects on both quality of life and the environment if certain requirements are met (Hagbert 2016; Huber et al. 2024; Lehner et al. 2024; Malmqvist & Brismark 2023).

Several studies examined the potential shareable resources and factors influencing the adoption of sharing practices, which have predominantly emerged within the past few years (Rathnayake et al. 2024). Bagheri et al. (2024) advocated that sufficiency in housing may positively influence many dimensions of wellbeing and sustainable development, such as health, social cohesion and economic sustainability. However, Francart et al. (2020) reported from the literature not only social benefits from space-sharing, such as access to affordable high-quality premises, social networks and decreasing isolation, but also potential problems due to overcrowding, noise or stress. Indeed, social value creation via activities and facilities management is a central task of housing companies to improve safety and trust among residents (Troje 2023).

Obstacles to sharing space also include the lack of available alternatives and infrastructures, partly due to the lack of incentives on the market for providing shared solutions and the reservation towards sharing with strangers (Hagbert 2016). Requirements for attractive space-sharing include a supportive infrastructure, the availability of, and access to, shared space, including the organisation of maintenance and cleanliness, along with formal rules and unspoken social contracts (Hagbert 2016; Huber et al. 2024). Resident-centred design methods are indeed needed to support the development of new housing concepts based on sharing and the adoption of more efficient, flexible and personalised ways of utilising the existing spatial resources (Pirinen & Tervo 2020).

According to Brinkø & Nielsen (2017), shared spaces can be defined in terms of their characteristics, such as core versus support facilities, access rights, how and when, but also in terms of the degree of sharing, varying from no sharing to invited, collaborative and complete sharing. Francart et al. (2020) stated that users consider tangible, organisational and social aspects of space-sharing. Tangible aspects include easy and affordable access to high-quality facilities and equipment. Organisational aspects are related to common rules and decision-making, communication, and booking arrangements. Social aspects include interaction and communication, trust-building, and developing a common understanding between users and towards the providers of shared space. Overall, Francart et al. note the importance of carefully designing shared spaces, their equipment, their way of use and the social interaction they can provide, along with observing and communicating user needs for further developing shared spaces.

Co-housing is one approach to sharing spaces that has been studied by several scholars. According to Beck (2020), co-housing comprises several independent homes in combination with shared spaces and facilities that support both living together and balancing privacy and communality. Co-housing households may share access to supplemental amenities such as common spaces within a building (e.g. meeting or working spaces, a shared kitchen, guest accommodation) or in common outdoor spaces (e.g. children’s playgrounds or outdoor cooking facilities). Based on a survey conducted in the US by Boyer & Leland (2018), the co-housing movement seems to be currently dominated by female, middle-aged, upper-middle-income, white and highly educated groups. However, they note that the interest is potentially wider, and mainstreaming co-housing is prohibited by a lack of suitable solutions. According to Beck (2020), shared indoor spaces in Danish common houses typically include laundry facilities, playrooms, guest rooms, office workspaces and workshops. Moreover, shared outdoor facilities, for example, can consist of green areas with playgrounds, kitchen gardens, fireplaces and greenhouses. Vestbro (2012) analysed various types of co-housing in Sweden and found that playrooms for children, hobby rooms, guest rooms, saunas and exercise rooms are commonly shared facilities. Both Vestbro (2012) and Beck (2020) define co-housing distinctly from collective or communal housing; they emphasise the role of space-sharing in allowing the use of common facilities for various types of mundane activities to save space—and eventually in developing building use (Brinkø & Nielsen 2017).

To summarise, the literature reports various aspects of sharing space and how they are perceived, but usually based on single examples at the level of specific houses or premises. However, it is hard to find studies on the perceptions of space-sharing at the level of the general population. This paper looks to fill this gap by analysing data from a Finnish nationwide survey and completes its statistical findings with qualitative answers provided by participants in the same survey. By focusing on household activities, it is possible to identify the potential for shared space and to develop building use (Brinkø & Nielsen 2017). Similar to Beck (2020) and Vestbro (2012), this study is guided by interest in whether shared spaces could serve a set of relatively mundane activities, but not focusing on communal activities as such.

2.3 Space-sharing in finland

Finland makes an interesting case to research low-carbon solutions because it has set ambitious goals to reach carbon neutrality by 2035. There is not much information available in Finland on the shared use of spaces in private housing, nor has it been at the focus of politics, despite the country having a government premises strategy focusing on increasing the efficiency of space used by governmental bodies (Ministry of Finance 2021).

The increase of home ownership has been a cultural and political target, especially during the increasing post-war urbanisation (Naumanen & Ruonavaara 2007; Ruonavaara 1996). Finns also appreciate ownership in relation to both goods and housing because of a long tradition of self-sufficiency (Repo et al. 2023), along with old-age security reasons (Naumanen et al. 2012). Single-family houses are still an aspiration for a majority of the population (Strandell et al. 2023). Despite a high level of home ownership (Statistics Finland 2022), the shared use of saunas and laundries in multistorey houses is a form of space-sharing that has been widely used during the past century. However, statistics on their commonness or their frequency of use, in either physical or financial terms, are poorly available. Other forms of space-sharing in housing are also not covered by statistics. Even shared flats are reported in official statistics only under ‘other households’, without specification.

Income has been identified as a factor influencing the environmental impacts of lifestyles. Sometimes this influence is strong, while at other times alternative factors play a larger role. Most studies on the correlation of income with sustainable behaviour cover especially nutrition- or energy-related behaviours. A few studies have examined space-sharing in the form of co-housing and have found that co-housing is more popular in certain groups with relatively low incomes, such as young adults (Grundström et al. 2024; Woo et al. 2019). Finland is facing a similar situation. While there is evidence that rising income tends to increase footprints (Lettenmeier et al. 2012; Salo et al. 2021), the correlation between income and behaviour is not especially explicit in, for example, the case of nutrition (Lehikoinen & Salonen 2019) or sustainable consumption in general (Salonen et al. 2014). This may be due to the relatively homogeneous society in Finland.

Regarding preferences towards space-sharing in Finland, only two surveys of university students from 2019 and 2022 are available, the results of which are published online without deeper analysis. The surveys enquired which kinds of shared spaces and other additional services the respondents would be interested in using, despite potential cost increases. According to the survey from 2022 (OTUS 2022), the students were particularly willing to share fitness rooms and saunas, followed by study and work spaces and well-equipped kitchens. The results from 2019 were similar, although a small potential effect of the COVID-19 pandemic was interpretable in the results from 2022.

According to a report by the Finnish Climate Change Panel (Linnanen et al. 2020), there is little interest in examining sufficiency in daily Finnish life. Hence, there is a clear research gap in understanding national-level household preferences for the most/least in-demand shared spaces. This applies especially to Finland, although limited research from other countries is also available, especially on the general population level.

3. Methods

3.1 Survey design and representativeness

The data used in this study are part of a larger survey exploring the preferences of Finnish citizens towards climate-wise housing and low-carbon construction policies. The survey instrument was planned and developed iteratively through multiple researcher workshops. These workshops enabled the identification of relevant and important space-sharing activities as well as information about other sharing economy-related questions in the survey (for the survey questions used in this paper, see the supplemental data online). The survey was targeted at Finnish citizens living in Finland, and was thus conducted in the two official languages, Finnish and Swedish, and also in English. The survey content was first designed in Finnish, and the contents were later translated into Swedish and English. Two pilot rounds were conducted to test the formulation of the survey items and the proper understanding of the questions. The first pilot included 16 interviews which were conducted in October 2021. The second pilot was undertaken in the three languages on the online survey platform Webropol between January and February 2022. In the second pilot, feedback and test responses from 55 individuals were collected.

To reach the target group, a simple random sample of 10,000 individuals was ordered from the official population records managed by the Digital and Population Data Services Agency of Finland. A third-party service was used to deliver an invitation by post with instructions for participation in the survey. Each participant had their own identification number to access the online survey on Webropol. The invitations were delivered at the beginning of March 2022. A reminder was distributed in early April. The survey remained open until 24 April 2022. The respondents were incentivised to respond by a random lottery draw.

A total of 1448 responses were received, reflecting a 14.5% response rate. The respondents were representative of the average household size (Table 1). In addition, the divisions of respondents between rural and urban areas and by house type were quite close to the national averages. However, the respondents were a bit older and included slightly more women than the original random sample. The collected sample was also more educated than the average Finnish population of over 15-year-olds. However, these differences were mitigated if accounting for the fact that the collected sample only included individuals aged between 18 and 80. The collected sample had a somewhat higher average income than the national average. Note that the average income was calculated for respondents by taking the median from each presented income category and weighting these with the relative shares of the respondents in each income category. Unfortunately, the national-level income distribution is not publicly available with the presented division. Overall, data representativeness was fairly good if both statistical considerations in relation to the Finnish population and the process of material gathering (i.e. random sampling) were accounted for.

Table 1

Descriptive statistics of the respondents and of the corresponding Finnish population.

| RESPONDENTS (N = 1448) | POPULATION IN FINLAND | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, average (years) | 52.7 | 49.4a |

| Household size, average | 2.4 | 2.4a |

| Gender (%) | ||

| Female | 53.3% | 51.1%a |

| Male | 46.7% | 48.9%a |

| Household gross income (€/month) | ||

| < €2,000 | 13.5% | – |

| €2,000–3,999 | 28.2% | – |

| €4,000–5,999 | 24.8% | – |

| €6,000–7,999 | 15.4% | – |

| €8,000–9,999 | 8.7% | – |

| > €10,000 | 6.1% | – |

| No response | 3.3% | – |

| Household gross income, average (€/month) | €4,920.0 | €4,309.1b |

| Education (%) | ||

| Primary, secondary (e.g. vocational degree) or other education | 55.6% | – |

| Higher education (university or applied sciences degree) | 44.4% | 33.0%c |

| Community type (urban–rural division) (%) | ||

| Town or city | 69.5% | 72.3%d |

| Sparsely populated area or small population centre | 29.9% | 27.7%d |

| Other or no response | 0.6% | – |

| Dwelling type (%) | ||

| Detached or semi-detached house | 51.2% | 47.8%e |

| Terraced house | 12.4% | 13.2%e |

| Apartment building | 34.9% | 37.7%e |

| Other or no response | 1.5% | 1.3%e |

[i] Note: aRandom sample (N = 10,000) obtained from the civil registry.

bDisposable mean income per household in Finland in 2021 (Official Statistics of Finland 2024).

cFinnish population of over 15-year-olds in 2021 (Official Statistics of Finland 2023a).

dGeographical information system (GIS)-based urban–rural classification for Finland and the Finnish population (Helminen et al. 2020).

eFinnish dwellings and housing conditions in 2021 (Official Statistics of Finland 2023b).

–, Unavailable national-level information.

3.2 Regression analyses

The binomial probit and negative binomial regression models were utilised to study factors linked with space-sharing perceptions (see Greene 2017 for further model details). In the binomial probit model, the dependent variable was a binary choice based on either ‘yes’ or ‘no’ responses towards one or more space-sharing activities. The purpose of the binary probit model was to estimate the probability that an individual with particular characteristics will state an interest in using at least one or none of the space-sharing activities. The binary probit model can be written as follows:

where i is an individual respondent; yi is the binary dependent variable, where 1 indicates ‘yes’ and 0 indicates ‘no’ towards one or more space-sharing activities; is the latent variable linking to the dependent variable; β is a vector of estimated parameters; Xi is a vector of explanatory variables; and ɛ is the normally distributed error term. The vector of β is estimated by maximum likelihood.

To address the degree of interest in space-sharing activities and not just positive or negative perceptions, a count data-based approach was appropriate. In the negative binomial model, the dependent variable indicated the number of space-sharing activities (0, 1, 2, …, 11) in which the respondent was interested. The formulation of the density used for the optimisation in the negative binomial model type 1 is as follows:

where

where Y is a discrete random variable; yi is the observed counts; λi relates to the mean; and θ is the overdispersion parameter. Again, β refers to estimated parameters and Xi to explanatory variables. The negative binomial model is an extension of the Poisson regression model that allows the variance of the dependent count variable to differ from its mean (Greene 2017). The negative binomial model with an additional overdispersion parameter may provide a better fit and more accurate parameter estimates than the Poisson model, when overdispersion is a feature in the data. The β parameters and the overdispersion parameter can be estimated via maximum likelihood.

3.3 Analysis of the open-ended question

The open-ended statement ‘[You have the] Opportunity to freely write about [your] thoughts on common spaces and areas’ was included in the survey. A total of 198 respondents wrote in this field. Response lengths varied from one word to a whole paragraph of 125 words. To analyse this qualitative material, responses were first organised into five main categories: (1) general resistance, (2) general neutral comments, (3) general support, (4) space-sharing in the context of rural areas and detached houses, and (5) activity- and/or space-related comments. The further analysis of these comments focuses on the justification of negatively charged perceptions as well as the activity- and/or space-related comments to illuminate the quantitative findings of the study. Regarding activity-related comments, the data were coded based on 12 spaces/activities that were referred to, with a focus on the functional aspect of sharing. The activities include cooking, leisure activities or festivities, remote work or study, indoor sports, exercising or using fitness equipment, laundry and drying, using a sauna, gardening, cooking on a barbecue, children’s play or playground, do-it-yourself (DIY), crafting and repair work, accommodating guests, and other, e.g. the use of storage space. Moreover, in the thematic analysis, three types of arguments about why not to share spaces were identified: (1) resistance as a matter of principle, (2) valuing privacy and/or lack of interest, and (3) organisational issues. Lastly, response samples were handpicked to support the quantitative findings.

4. Results

4.1 Opinions on and experiences of sharing activities

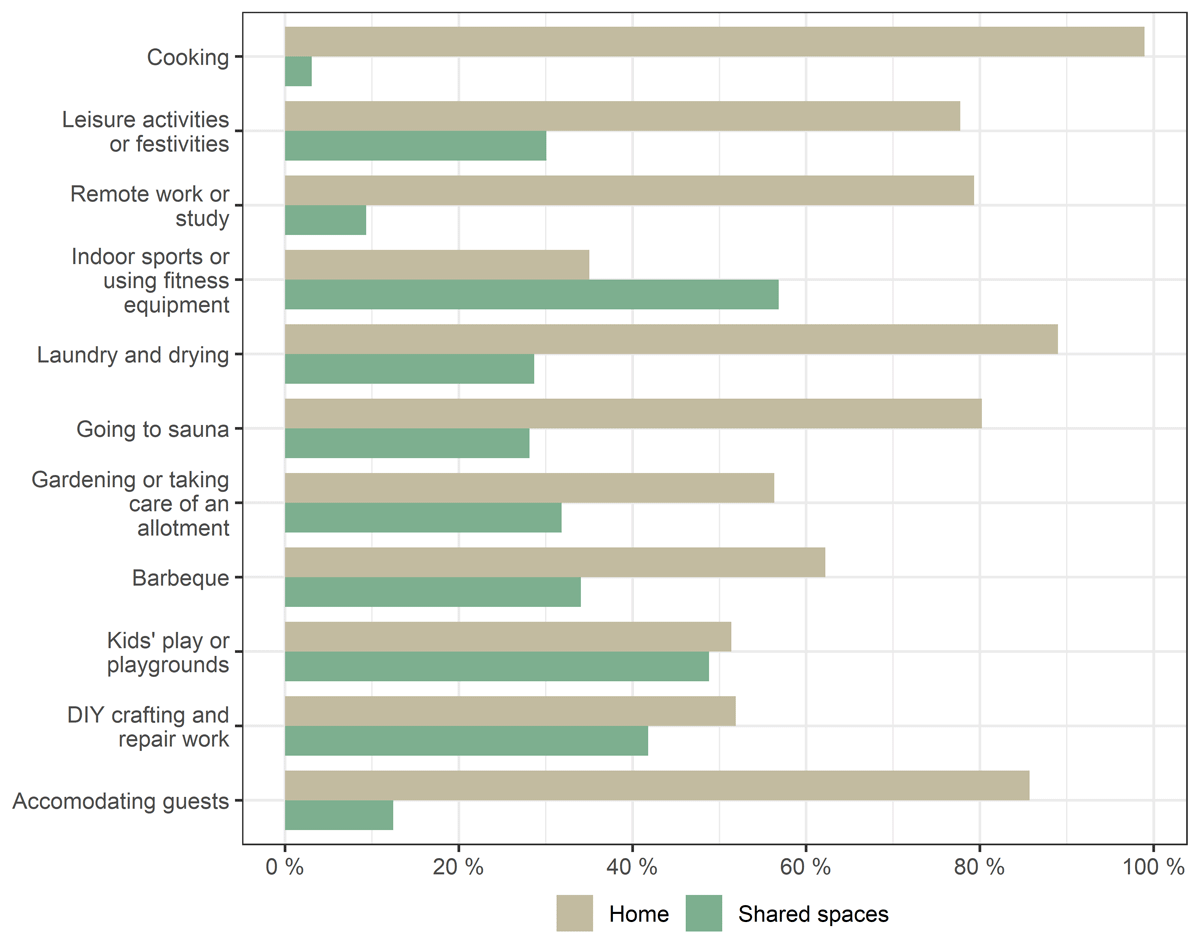

Figure 1 presents the percentages of respondent views regarding the question: ‘What activities do you think are important to be able to do in the home and what activities in common spaces of the housing association or neighbourhood?’ (for the survey questions, see the supplemental data online). Note that the answers are not mutually exclusive, i.e. the proportion of summed replies can add up to over 100%. According to Figure 1, the most popular activities to be done at home are cooking, leisure activities and festivities, remote working or studying, and accommodating guests. Vice versa, indoor sports or the use of fitness equipment are among those that are most often perceived to be performed in shared spaces. Some activities are rather equally split across the home and shared spaces, including DIY crafting and repair work, and children’s play activities. These results are also understandable in light of Finnish housing traditions, which, for example, rarely include common space for accommodating guests overnight as part of the residential housing complex, whereas having a shared playground or gym is more common.

Figure 1

Response distribution to the question: ‘What activities do you think are important to be able to do in the home and what activities in common spaces of the housing association or neighbourhood? (N = 1436).

In their responses to the open-ended question, 100 survey participants described their viewpoints in relation to specific spaces or activities. These comments indicated an interest in space-sharing. For example, sauna and laundry facilities, which have traditionally been shared in Finnish apartment buildings, are mainly reflected upon from the viewpoint of practical perspectives linked to tangible aspects of space-sharing. Practical perspectives include experiences regarding the types of booking systems that are considered functional. Moreover, those who use their private saunas less frequently might appreciate better-equipped shared saunas:

I like spaces you can you use when necessary. For example, a club room or similar that could be used as a party space would be nice. In addition, a sauna department would be nice if it would be fancier than the home sauna. We only seldom use the sauna.

(response 157)

Indoor gyms and indoor spaces that can be used for organising parties triggered some enthusiasm. Moreover, some outdoor spaces were also considered from the perspective of increased possibilities for socialising with neighbours and building a sense of community:

It would be great if the apartment buildings had large shared accessible lounges, gyms, and party rooms. It would be easier for people to get to know their neighbours and find like-minded spirits and neighbourly help, especially for the lonely and the elderly, but of course for everyone.

(response 70)

Shared spaces could create a sense of communality, so a grilling possibility in the yard would be a good idea.

(response 48)

Indeed, the responses highlight the fact that space-sharing is valued, as it can ‘bring added value to housing and increase comfort’ (response 65). Based on these responses, the sense of communality is a key value related to space-sharing; the use of shared spaces facilitates becoming acquainted with the neighbours. However, from a practical perspective, respondents reflected their concerns and experiences, e.g. by noting that space-sharing is more easily organised under larger housing associations or by stressing that the willingness to share space should not lead to over-efficiency of space design within apartments.

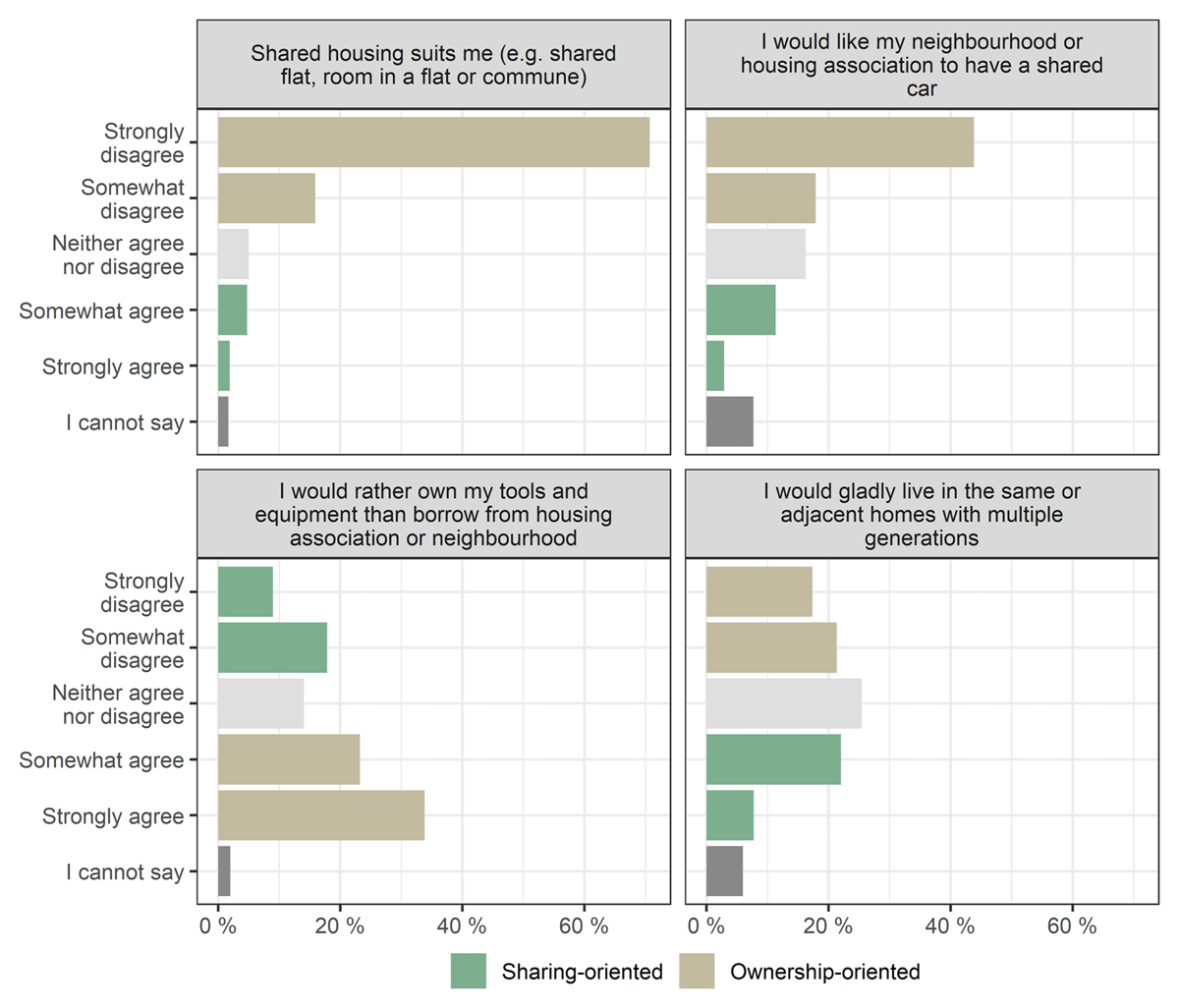

Overall, the respondents’ stances towards shared housing are not very positive, as also shown by Figure 2: only 7% agree or strongly agree with shared housing being suitable to their living style (N = 1430), and 14% agree or strongly agree with the possibility of having a shared car in the neighbourhood or in their housing association (N = 1428). A slightly higher proportion (30%) expressed a willingness to live in the same or in an adjacent apartment as different-generation relatives (N = 1433). A fairly large proportion of respondents expressed an indifference to the choice regarding sharing economic activities. Hence, it can be concluded that the level of awakening toward space-sharing is not yet very great, and more promotion and awareness-building activities are still needed if such practices are to be the mainstream in Finland.

Figure 2

Response distribution of the four background statements concerning housing preferences.

Note: The colour-coding of responses reflects those in favour of sharing-oriented pro-environmental behaviour in contrast to ownership-oriented behaviour.

In the open-ended responses, frequent appreciation was shown especially for tool-sharing, including wheelbarrows and ladders, and for incorporating facilities for DIY projects, repair and maintenance:

A communal DIY area would be nice, for people to create and improve their homes themselves. Power tools and working areas can be quite expensive. Having an area to hold workshops where people can be taught basic DIY and maintenance would also be beneficial to the community. Personally, I prefer my own workshop and work area.

(response 168)

4.2 Regression results on the preferences toward shared spaces

Regression-based approaches were used to model citizen interest in space-sharing. For the regression analyses, 39 respondents were excluded due to missing observations of the dependent or explanatory variables. The final sample included 1409 fully completed responses. For details of the dependent variables, see Table 2. Table 3 introduces the explanatory variables, including socio-demographic details, home characteristics, and climate attitudes and habits.

Table 2

Response distributions of two dependent variables.

| DEPENDENT VARIABLE IN THE NEGATIVE BINOMIAL MODEL: NUMERICAL COUNT OF SPACE-SHARING ACTIVITIES | FULL SAMPLE FREQUENCY (N = 1448) | FULL SAMPLE PROPORTION (%) (N = 1448) | FINAL SAMPLE FREQUENCY (N = 1409) | FINAL SAMPLE PROPORTION (%) (N = 1409) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 364 | 25% | 359 | 25% |

| 1 | 144 | 10% | 140 | 10% |

| 2 | 155 | 11% | 153 | 11% |

| 3 | 144 | 10% | 142 | 10% |

| 4 | 163 | 11% | 158 | 11% |

| 5 | 109 | 8% | 105 | 7% |

| 6 | 138 | 10% | 136 | 10% |

| 7 | 78 | 5% | 76 | 5% |

| 8 | 80 | 6% | 80 | 6% |

| 9 | 43 | 3% | 42 | 3% |

| 10 | 14 | 1% | 14 | 1% |

| 11 | 4 | 0% | 4 | 0% |

| DEPENDENT VARIABLE IN THE BINOMIAL PROBIT MODEL: WILLINGNESS FOR SPACE-SHARING ACTIVITIES | ||||

| 0 | 364 | 25% | 359 | 25% |

| 1 (if count of space-sharing activities ≥ 1) | 1,072 | 74% | 1,050 | 75% |

| Missing observations | 12 | 1% | 0 | 0% |

Table 3

Explanatory variable descriptions and descriptive statistics for the final sample (N = 1409).

| EXPLANATORY VARIABLES | DESCRIPTION | MEAN OR SHARE | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic characteristics | |||

| Age | Respondent’s age | 52.7850 | 17.3678 |

| Female (1 if yes) | Respondent is female | 0.5351 | |

| High education (1 if yes) | Respondent has an applied sciences or university degree | 0.4471 | |

| City-like (1 if yes) | Respondent lives in a city or urban residential area | 0.6962 | |

| Home characteristics | |||

| Floor area/hhsize | Floor area (m2) per inhabitant in the respondent’s home | 52.0547 | 32.5505 |

| Rental (1 if yes) | Respondent lives in a rental dwelling | 0.2186 | |

| Detached house (1 if yes) | Respondent lives in a detached or semi-detached house | 0.5117 | |

| Attitudes and habits | |||

| CChuman (1 if yes) | Respondent believes that the climate is changing due to human activity only or for the most part | 0.7204 | |

| Uses car (1 if yes) | Respondent drives a petrol or diesel car at least weekly | 0.7842 | |

| Eats meat (1 if yes) | Respondent eats red meat as the main meal at least weekly | 0.6636 | |

The estimation results for the binomial probit and negative binomial regressions are given in Table 4. The dependent variable in the binomial probit model was a binary choice constructed based on either ‘yes’ or ‘no’ responses towards one or more space-sharing activities. A total of 75% of respondents indicated a willingness for space-sharing. Instead, in the negative binomial regression, the dependent variable is the sum of space-sharing activities (0, 1, 2, …, 11) in which the respondent is interested, in turn addressing the degree of interest in space-sharing activities and not just a positive or a negative interest (Table 2). On average, respondents are willing to share 3.25 spaces. Note that the negative binomial is found to fit these count data best based on the overdispersion test proposed by Cameron & Trivedi (1990), rejecting the Poisson distribution (i.e. the variance of the dependent variable is greater than its mean).

Table 4

Results of the binomial probit and negative binomial regression models.

| VARIABLE | BINOMIAL PROBIT | NEGATIVE BINOMIAL | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COEFFICIENT | SE | T-RATIO | P-VALUE | COEFFICIENT | SE | T-RATIO | P-VALUE | |||

| Constant | 0.9249 | *** | 0.2381 | 3.8839 | 0.0001 | 1.2411 | *** | 0.1416 | 8.7635 | 0.0000 |

| Age | –0.0027 | 0.0026 | –1.0338 | 0.3012 | –0.0021 | 0.0016 | –1.3406 | 0.1800 | ||

| High education | 0.0305 | 0.0814 | 0.3748 | 0.7078 | 0.0186 | 0.0490 | 0.3791 | 0.7046 | ||

| Female | 0.0888 | 0.0773 | 1.1492 | 0.2505 | 0.1041 | ** | 0.0472 | 2.2050 | 0.0275 | |

| City-like | 0.3517 | *** | 0.0873 | 4.0306 | 0.0001 | 0.2995 | *** | 0.0616 | 4.8610 | 0.0000 |

| Floor area/hhsize | –0.0010 | 0.0012 | –0.8135 | 0.4159 | –0.0015 | * | 0.0009 | –1.7035 | 0.0885 | |

| Rental | 0.2662 | ** | 0.1290 | 2.0640 | 0.0390 | 0.0917 | 0.0658 | 1.3945 | 0.1632 | |

| Detached house | –0.4470 | *** | 0.0967 | –4.6206 | 0.0000 | –0.3591 | *** | 0.0598 | –6.0025 | 0.0000 |

| CChuman | 0.2337 | *** | 0.0846 | 2.7633 | 0.0057 | 0.2522 | *** | 0.0547 | 4.6066 | 0.0000 |

| Uses car | –0.3175 | *** | 0.1142 | –2.7795 | 0.0054 | –0.2112 | *** | 0.0606 | –3.4854 | 0.0005 |

| Eats meat | –0.0527 | 0.0869 | –0.6066 | 0.5441 | –0.1250 | ** | 0.0501 | –2.4922 | 0.0127 | |

| Alpha | 1.7859 | *** | 0.1739 | 10.2717 | 0.0000 | |||||

| Model characteristics | ||||||||||

| LL | –713.33 | –3,111.66 | ||||||||

| LL(0) | –799.66 | –3,468.85 | ||||||||

| McFadden pseudo-R2 | 0.11 | 0.10 | ||||||||

| AIC/N | 1.028 | 4.43 | ||||||||

| Respondents (N) | 1,409 | 1,409 | ||||||||

| Parameters (K) | 11 | 12 | ||||||||

[i] Note: AIC = Akaike information criterion; LL = log-likelihood.

Significance at the *0.1, **0.05 and ***0.01 levels.

Overall, the binomial probit and negative binomial regression models reveal two different perspectives regarding attitudes towards space-sharing; the results, therefore, cannot be directly compared with each other. In essence, the binomial probit model focuses on revealing whether an individual has any interest toward space-sharing and what factors are associated with this interest, whereas the negative binomial model provides further insights concerning an individual interest to share an increasing number of spaces and what explains this fact. From a housing sufficiency perspective, there is no a priori preference to either approach.

Based on the results from the binomial probit regression, it can be observed that having climate change awareness and living in a city-like location (including suburban areas) or in a rental home are positively associated with an interest in space-sharing. Instead, variables negatively linked with a willingness to share spaces are regular petrol or diesel car-driving and living in a detached house. Socio-demographic variables (age, education or gender) or variables associated with sufficiency in housing (measured as m2 per inhabitant) or with eating meat products do not show significance in explaining a willingness for space-sharing.

The model using negative binomial regression shows that climate change awareness and living in a city-like location are positively associated with an interest in sharing more spaces, whereas negative effects emerge from variables describing meat-eating, petrol or diesel car-driving, and respondents living in a detached house. In this model, larger household floor area per inhabitant decreases the willingness to share more spaces. This implies that sufficiency in housing is linked with space-sharing preferences, especially when the willingness to share several spaces is considered. Females are more willing to share different spaces than men. Other background variables are not statistically different from zero.

Income and second-home ownership were also tested as explanatory variables in both regressions. However, they were not included in the final regressions because of their minor explanatory power. Furthermore, 42 additional missing observations for the income variable decreased the number of respondents in the final sample used for the analyses.

Despite climate change awareness being positively associated with the willingness to share spaces, this was not visible in the open-ended responses. Only one respondent (no. 104) reflected on space-sharing from an ecological viewpoint—the response pointed out the misfortune that housing companies tend to avoid keeping shared saunas up-to-date and to remove laundry and drying rooms from use. Both of these cause unecological consequences because the activities need to be moved into private spaces instead. The social aspect of a stronger sense of communality was more frequently expressed as a driving factor.

Moreover, in their open-ended responses, some respondents reflected on their reasoning behind choosing either shared or owned spaces:

For most of the questions above where I selected both, the premise of my own home is the first choice, and common spaces [come] second [only] if it is not possible to have [a certain amenity] in my own home.

(response 42)

Shared spaces are a great thing, as long as apartments are built spaciously enough to fit normal furniture like, e.g. a dining table, bed, sofa etc. that is, the minimum size should be a bit more than 20 square metres. In my opinion, shared DIY and bike repair spaces, as well as sauna and grilling spaces are nice and necessary in a community of multistorey buildings.

(response 173)

4.3 Resistance to space-sharing among respondents

As the above quantitative analysis has shown, not all respondents are enthusiastic about sharing spaces. The responses to the open-ended question showcased three categories of resistance, namely: resisting space-sharing as a matter of principle, lacking personal relevance and focusing on the functionality of space-sharing.

Resistance as a matter of principle is a specific discourse that only a few respondents (N = 4) use in their answers, but it is distinctive. In these responses, communal space is associated with Communism, and it is not considered suitable for modern Western societies where individualism and the privacy of the home are valued. This type of resistance draws from strong cultural and/or political positioning.

The second type of respondent resistance (N = 33) includes a variety of expressions showing a lack of interest and experience with or access to shared spaces, with a special emphasis placed on the high personal valuing of privacy. However, the answers are typically very brief, such as ‘not for me’, and are thus difficult to interpret more thoroughly. Nevertheless, the issue seems to be intertwined with social issues. Responses also characterised their various strategies of how to use or avoid shared spaces:

It is nice if there are shared spaces, however, [my] own peace and privacy are more important than an overt sense of community together with the neighbours.

(response 36)

If I had to use shared spaces, I would move away as soon as possible, and [prior to moving] I would try to use shared spaces at such hours that none of the neighbours would be using them […].

(response 28)

The third category of replies on how respondents perceived resistance is more practical by origin. The focus is on functional issues, also providing examples about why such arrangements would not work or what aspects should be accounted for before they could consider supporting space-sharing (N = 19). Typically, concerns are related to users not following space-sharing rules, misuse, safety issues, stealing or causing a mess. The development of clear, multilingual, commonly agreed-upon rules, functional booking and cleaning systems, establishing user fees, and nominating responsible people, such as devoted housing managers and ‘suitable’ neighbours, are considered possible solutions. In addition to having good housing management in place, the atmosphere among residents should be open and communicative, so that ‘everyone dares to talk and listen during the housing association meetings’ (response 186). Moreover, it is expected that the residents should know each other sufficiently well to be interested in using shared spaces that already exist in many newly built residential blocks of flats. Similarly, it is suggested that all new buildings should have predesigned concepts for shared spaces, including for maintenance and cleaning.

5. Discussion and conclusions

5.1 Research and policy implications

Several interesting observations can be made about space-sharing based on the analysis of the Finnish citizen survey from 2022. Regarding the first research question on citizen interest towards space-sharing, 75% of the respondents indicated at least some willingness for the given space-sharing activities, which can be interpreted as a substantial proportion at the national level. However, the popularity differs greatly across a range of activities and is highest with indoor sports activities or the use of fitness equipment in shared spaces. On the other hand, some household activities, such as cooking, are seen to belong more strictly in private spaces. This orientation can be interpreted as signalling heterogeneity in sharing practices. A similar heterogeneity was observed in a survey of Finnish students regarding their preferences towards shared space and services (OTUS 2022).

The results also imply strong, culturally rooted traditions that favour some sharing activities over others, such as the use of housing association laundry facilities or saunas. On the other hand, due to market demand and increased quality requirements, sauna and laundry facilities are nowadays commonly included even within small new residential flats in Finland.

It is important to note concurrently that only a few per cent of respondents indicated an interest in communal living solutions (Figure 2). Furthermore, car-sharing was not a high-interest activity and neither was living in the same household as other generations of the family. Indeed, co-housing or communal housing are still niche phenomena in Finland. Regarding the analysis conducted for the second research question using a thematisation of the open-ended responses, some respondents even compared it with a Soviet-period housing solution.

It also became obvious from the qualitative data that reduced housing space can have negative associations among citizens. The underlying reasons could, for example, relate to hobbies such as gardening or carpentry becoming more difficult to undertake. These findings resonate with those of Lehner et al. (2024), which indicated little initial interest among citizens in reducing their living space voluntarily. However, positive effects from living ‘smaller’ may emerge, including increased time for leisure activities, closer proximity to services or enhanced connections within the neighbourhood after gaining more practical experience (Lehner et al. 2024). It is thus possible that a greater level of interest towards (and fewer prejudices against) space-sharing may also gain ground in Finland if positive experiences accumulate and become visible.

Regarding the third research question on nationwide influencing factors, greater climate change awareness was positively associated with an interest in sharing spaces irrespective of the two statistical estimation models used in the regression analysis. In line with this rationale, there was a negative effect on the preference toward space-sharing associated with carbon-intensive dietary and mobility choices. Despite respondents with low-carbon lifestyle choices having a greater interest in sharing space, the ecological improvement potential of space-sharing, as stated by Sandberg (2018) and Malmqvist & Brismark (2023), does not appear to be a major driver for perceiving the benefits of sharing space. Rather, respondent views point to a focus on comfort, usability and social aspects when promoting space-sharing (see also Francart et al. 2020; Pirinen & Tervo 2020). Also, the insights from the open-ended question on space-sharing revealed more visibly communal rather than environmental aspects. The identified stronger focus on communality highlights the social aspect of sharing as a motivational factor that has also been noted by Francart et al. (2020) and Lehner et al. (2024). However, in the Finnish context, it became evident that not everyone appreciates an increase in communality, as many prefer greater privacy, and residents with such views may be difficult to persuade to become users of shared spaces.

Furthermore, according to the results explaining the propensity of preferring various shareable spaces, a larger household floor area per inhabitant decreased the willingness to share more spaces. This gives some indication that sufficiency in housing is linked with space-sharing preferences, while this coefficient was insignificant when using the other estimation method focusing on dichotomous ‘yes/no’ perceptions of space-sharing.

In addition, the findings of the regression analyses indicate that the effects of socio-demographic background variables were mostly insignificant (with the exception that women were more willing to share spaces than men). This result implies that the Finnish population is rather homogeneous in terms of the affecting socio-demographic characteristics such as age or income. The finding of the limited explanatory power of socio-demographic variables is also in line with Ruokamo et al. (2024), who used the same survey data but with a focus on preferences toward renewable building materials as well as renovations over demolition and newly built houses as alternative decarbonisation pathways. On the other hand, living in urban areas and other than detached houses were positively associated with space-sharing interests. This may reflect the perspective that space-sharing solutions are less common and not needed as much along with possibly being more difficult to establish outside urban areas and in detached house environments. Hence, the promotion of shared living space is likely more effective in apartment-dominant urban areas, and with progressing urbanisation space-sharing solutions may well become more preferrable over time. Progressing urbanisation, with its high costs of living space, especially in the growing Helsinki capital region, can act as a driver for those who wish to give more weight to the premium location of their home instead of having a spacious house in a more remote and cheaper location.

Overall, the results from this study add evidence that, in the case of Finnish citizens, space-sharing as an operationalisation of housing sufficiency receives mixed responses, and information bottlenecks and prejudices are likely to exist. Norms from peer groups and the media toward what constitutes ‘an ideal home’ can be a barrier among individuals to choose higher housing sufficiency. Hence, while the conclusion is that the importance of social aspects in advancing housing sufficiency is clear, the perceived effect can be either positive or negative in the context of space-sharing depending on the individual. To reduce consumption-based emissions in future via mainstreaming more efficient space use, obviously a further need exists for developing both the tangible and especially the organisational aspects of sharing (Francart et al. 2020). This would mean better and clearer user rules, establishing functional booking and fee systems, and building awareness towards responsible user practices, along with ensuring easy access to shared spaces and designing them to be attractive places. In conclusion, Finland still appears to have a great deal of untapped potential for developing space-sharing practices as an avenue toward the decarbonisation of the built environment.

5.2 Limitations and future research

It is worth noting that the analysed data were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic when, for example, wide-scale remote working policies were in place. During the period of social distancing measures, many people moved several of their daily activities into their homes and avoided public spaces. This may be reflected in the results of this study in two opposing ways: while daily office visits and encounters with colleagues diminished in number, people may have noticed that their apartments were too congested to incorporate new remote work activities. Hence, they could have been turning towards their housing community for both social relations and shared spaces. Alternatively, for health reasons, they could have withdrawn from using shared spaces in the apartment buildings to avoid their neighbours.

It should also be noted as a study shortcoming that two forms of co-housing enable different interpretations in terms of climate effects. Emissions are likely smaller if co-housing is about a household living in a very compact apartment, while emissions do not necessarily decrease if individual homes are grouped around a shared ‘communal building’ with non-compulsory extra facilities. The first option is in line with the aspiration toward higher housing sufficiency, whereas the second option may be more strongly related to increasing the quality of housing but without a concern for sufficiency or for avoiding emissions.

There is still ample room for research on sufficiency in housing and sharing of living spaces. For example, modern housing designs often aim at efficient space use due to high building costs, which gives weight to space-sharing. Moreover, novel arrangements such as co-housing (Beck 2020; Francart et al. 2020), group self-building projects including more common spaces to enhance communality (Heffernan & Wilde 2020), or an emerging trend of densifying urban areas via rooftop extensions in Northern Europe (Holtström et al. 2024) are fascinating topics to investigate further from the viewpoint of citizen acceptance.

From a policy perspective, while mainstreaming the space-sharing phenomenon happens through individual choices, decision-making is also strongly shaped by available housing market offers, existing urban infrastructure and legal frameworks (Bagheri et al. 2024). This gives room to analyse small-scale sharing initiatives, typically observed at the municipal or neighbourhood level. Further attention is also needed to examine housing sufficiency in connection with (1) municipal and national housing policies and (2) programmes promoting lower housing emissions.

To gain an in-depth understanding of the potential of space-sharing in housing, future research should also focus on the ways in which shared spaces are used and managed in real life. In addition, elderly or student housing could offer an interesting case for delving into social aspects of housing and shedding light on people’s willingness to share spaces.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the anonymous referees for their valuable comments; and the consortium partners for participating in the survey planning.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data accessibility

The data protection statement provided to respondents prohibits publicly disclosing the data.

Ethical approval

The survey respondents gave their consent for the use of the project results in this publication. The research fully adheres to the guidelines of ethical research by TENK, the Finnish board of scientific integrity and ethics.

Funding

This work was conducted as part of the DeCarbon-Home project funded by the Strategic Research Council (grant numbers 358343 and 358276).

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at: https://doi.org/10.5334/bc.453.s1