Table 1

Energy sufficiency (ES) in buildings: area, action and unit of measurement

| AREA | ES ACTIONS | UNIT OF MEASUREMENT |

|---|---|---|

| Space |

| m2/cap rooms/cap |

| Design and construction |

| Yes/no |

| Equipment |

| n, kW |

| Use |

| °C Operational hours |

[i] Note: aClosing windows while heating or cooling a room or a building, shock ventilation with short-term wide window-opening instead of long-term tilting.

Source: Adapted from Bierwirth & Thomas (2019a).

Table 2

Energy saving measures according to energy sufficiency (ES)-stringent, ES-broad and energy efficiency (EE)

| MEASURE | ES | EE (AS DEFINED UNTIL NOW) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ES-STRINGENT | ES-BROAD | ||

| Reducing energy demand by avoiding or reducing an energy service following prescribed standard values (as defined in norms) (e.g. reducing the heating temperature, reducing the number of light bulbs in a corridor) | × | × | |

| Reducing energy demand by avoiding or reducing an energy service beyond the standard levels (e.g. reducing heating temperature, reducing the number of light bulbs in a corridor) | × | × | |

| Reducing energy demand automatically by avoiding or reducing an energy service that provides no physical benefit (e.g. automatically turning off lights in unused corridors at night) | × | × (EE through smart control) | |

| Reducing demand manually for an energy service that provides no physical benefit (e.g. manually turning off lights when leaving a room) | × | × | × (EE behaviour) |

| Reducing energy demand by reducing process capacity or size to meet real needs (e.g. reducing cooling zone area to minimise the duration of compressor use) | × | × | |

| Reducing energy use through corrective adjustments (e.g. tuning a previously misconfigured heating system) | × | × | |

Figure 1

Total final energy savings by end-use categories and according to the two definitions (n = 279).

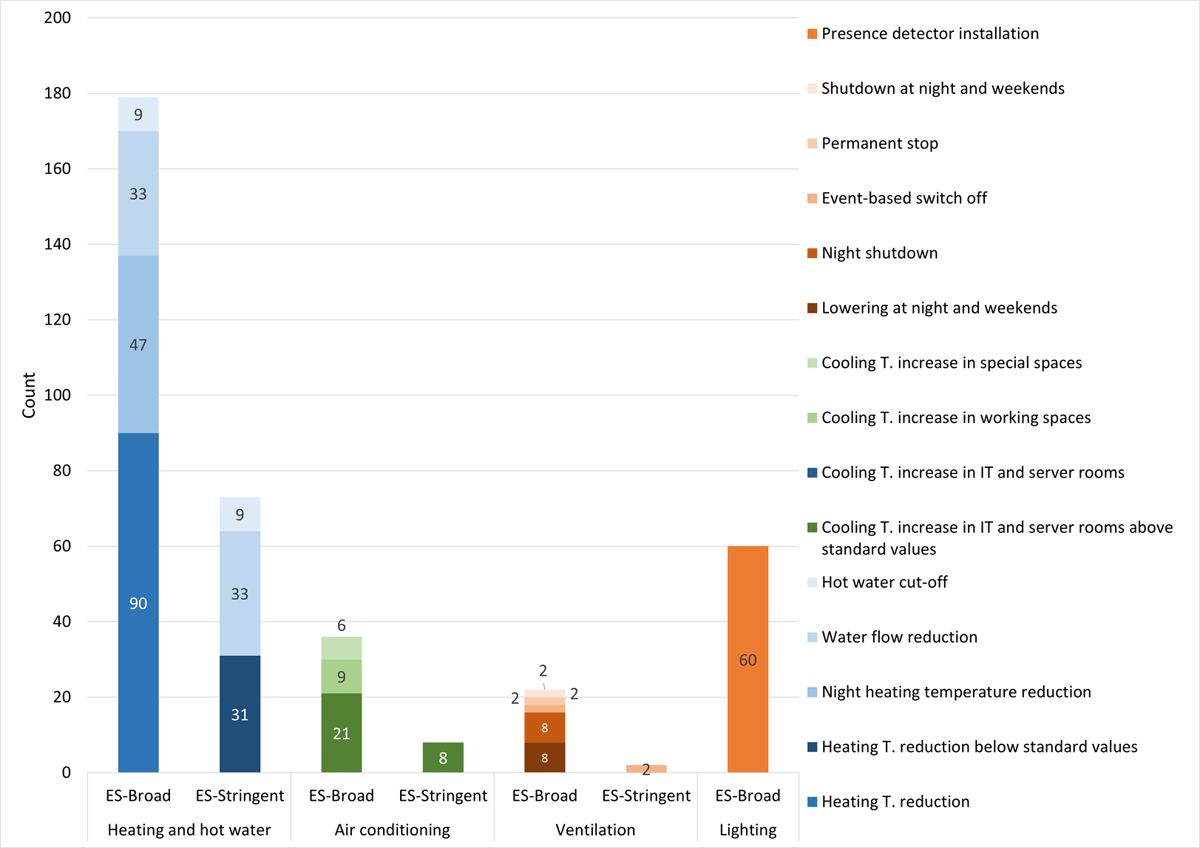

Figure 2

Types of energy sufficiency (ES) measures by end-use category (n = 297).

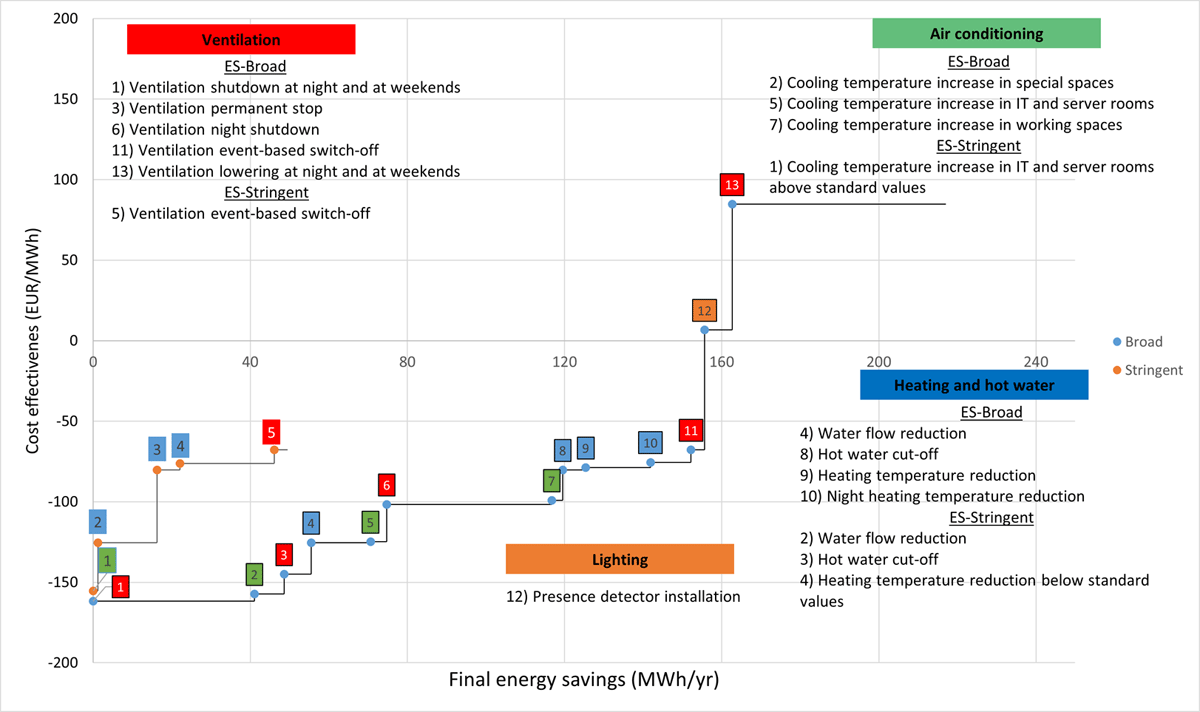

Figure 3

Energy cost-curve of energy sufficiency (ES) measures according to ES-broad and ES-stringent (n = 297).

Note: Cost curves show the ES measures’ cost-effectiveness (y-axis) as a function of the energy savings (x-axis).

Table 3

Additional energy sufficiency (ES) measures addressing equipment and appliances with descriptions, examples and their impact estimated by the auditors

| ES MEASURES ADDRESSING … | DESCRIPTION | EXAMPLE | FINAL ENERGY SAVINGS RELATIVE TO FINAL ENERGY USE BEFORE THE MEASURE (%) | PAYBACK TIME (YEARS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coffee machines | Coffee machines often stay on standby between uses and at night. Install a timer to set the machine’s automatic switch-off time | Use a timer to switch off the machine at night and outside working hours all year. Standby power is 100 W; time outside working hours is 4680 h; savings: 468 kWh/year | 10% | 0.6 |

| Kitchen equipment | Some kitchen equipment, such as ovens and plate-warmers, are turned on long before the effective period of use | Instead of 12 h/day, the plate-warmers are only switched on during lunch and dinner service time; saving: 6 h/day | 50% | 0 |

| Video-conferencing equipment | Electronics located in video-conferencing rooms are permanently on standby | Raise awareness of turning off monitors after a session | 50% | 0 |

| Final energy use night band | Important baseloads at night are noticed in some SMEs’ final energy use measurements | The main factors behind this baseload can be appliances on standby (computers, printers, coffee machines, etc.) and uncontrolled ventilation and process-cooling equipment | 15–20% | Case-specific |

[i] Note: SMEs, small and medium-sized enterprises.

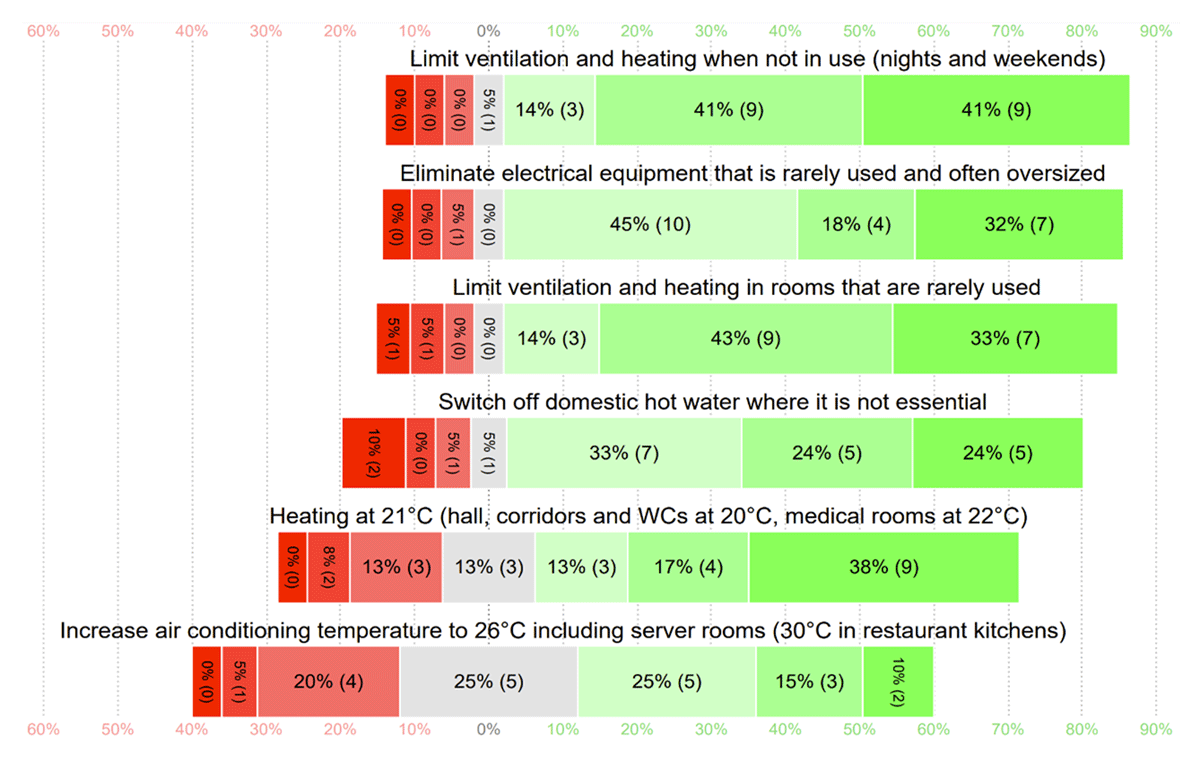

Figure 4

Acceptability of energy sufficiency (ES) measures according to the small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (n = 20).

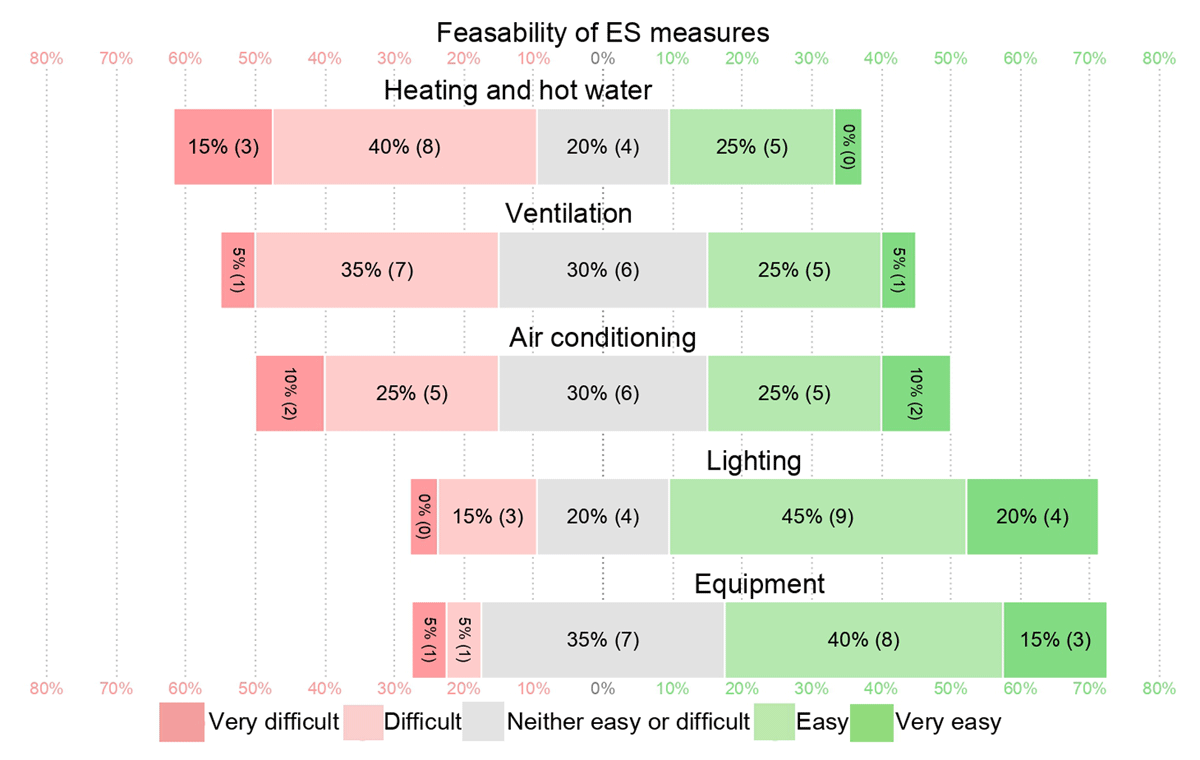

Figure 5

Feasibility of energy sufficiency (ES) measures according to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (n = 20).

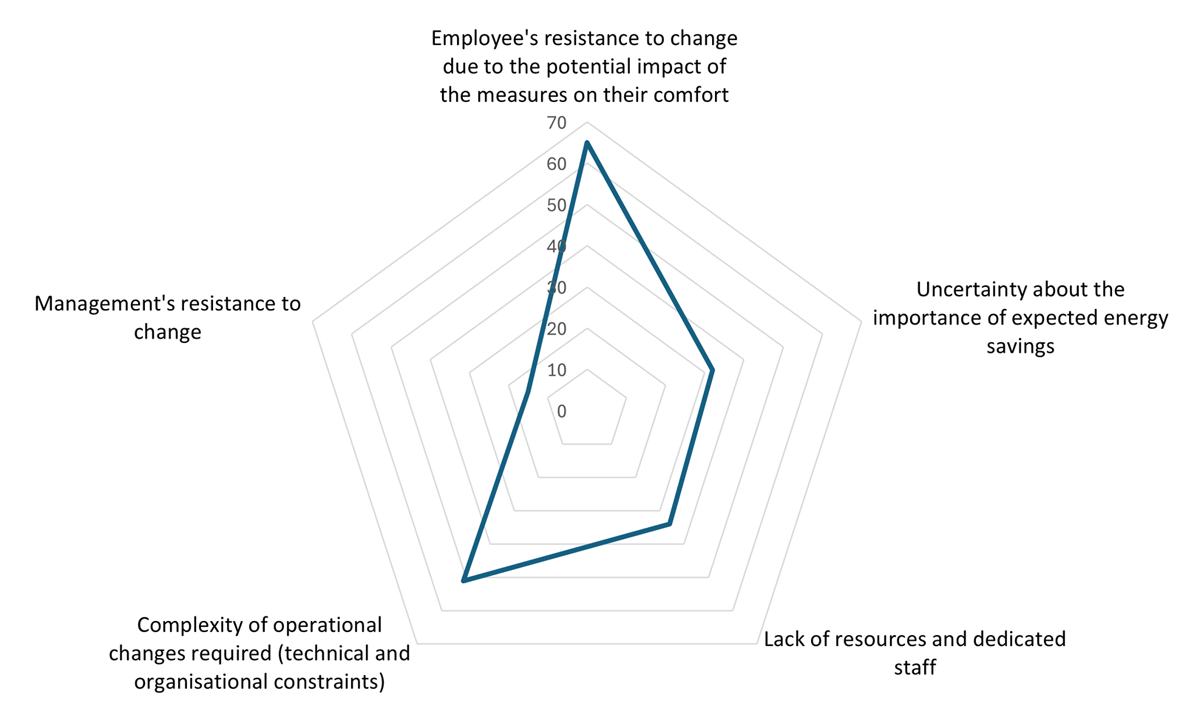

Figure 6

The ranking of barriers to implementing energy sufficiency (ES) measures according to the small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (n = 19).