1. Introduction

In pursuit of a sustainable energy system, many countries have chosen energy efficiency (EE) as a key element of their energy policy, aiming to make energy demand and supply more efficient. The benefits of EE include reducing greenhouse gas emissions, lowering energy bills and creating jobs (IEA 2014; Patel et al. 2021). Different policy instruments and programmes have been activated to promote EE among end-users. However, a lower level of EE policy implementation is threatening recent gains from EE worldwide. In the European Union, and since 2014, EE improvements have slowed significantly (Bosseboeuf 2023; Lapillonne 2021). This can at least partly be explained by higher activity (e.g. population and/or economic growth) and by rebound effects (Bertoldi 2022; Guibentif & Patel 2023). Recent studies have called for complementing EE policies and measures with energy sufficiency (ES) to limit the demand for energy services of end-users and, therefore, achieve absolute reductions in energy consumption (Bertoldi 2022; Niessen & Bocken 2021; Sandberg 2021). The European CLEVER scenario aligns with this and proposes a new decarbonisation pathway for Europe grounded in the integration of sufficiency in energy and climate modelling as well as policymaking (Bourgeois et al. 2023). In Switzerland in 2020, the GEA (2020) drew up an energy master plan with targets fixed for 2030 and 2050. This document, for the first time, clearly sets out ES as a main work axis linked to quantifiable energy reduction targets.

Many different definitions of ES have been discussed in previous studies (Bertoldi 2022; Best et al. 2022). Most definitions evoke the capping of energy consumption to a decent minimum level that delivers basic needs—in contrast to excessive wants—for energy services while respecting planetary boundaries (Ba Bagheri et al. 2022; Bierwirth & Thomas 2019a; Spengler 2016). Concepts of wellbeing and equity as other conditions to achieve sufficiency are sometimes also included (Fawcett & Darby 2019; IPCC 2023; Wiese et al. 2023). Some of these studies distinguish between ES as a state and ES actions (Best et al. 2022; Bierwirth & Thomas 2019a), and define the latter as actions that reduce energy demand to reach the ES state in which people’s basic needs for energy services are met equitably and ecological limits are respected. Other studies differentiate ES from EE by defining ES as a strategy for achieving absolute reductions when using energy services beyond technical efficiency (Best et al. 2022; Bierwirth & Thomas 2019a; Samadi et al. 2017; Toulouse et al. 2019).

Many studies discussed ES in conceptual terms (Jungell-Michelsson & Heikkurinen 2022; Samadi et al. 2017; Toulouse & Gorge 2017; Zell-Ziegler et al. 2021), and most ES studies focusing on specific sectors refer to private households and individuals’ choices for mobility and food (Bertoldi 2022; Gaspar et al. 2017; Moser et al. 2015; Okushima 2023; Seidl et al. 2017; Vita et al. 2019). Only a few ES studies cover business strategies (Bocken & Short 2016; Freudenreich & Schaltegger 2020; Niessen & Bocken 2021), and even fewer concern non-residential buildings. Bierwirth & Thomas (2019a: 6) defined an energy-sufficient building as an ‘adequate space thoughtfully designed and constructed and sufficiently equipped for reasonable use’ and thus identified four areas for ES actions in buildings: space, design and construction, equipment, and use. They then identified potential ES actions in each area (Table 1) and indicators for estimating the energy savings potential. Due to a lack of data, the authors could only estimate the energy saving potential for space heating due to reduced floor area per capita in residential buildings in European countries. An overall quantitative estimate of energy savings by ES in non-residential buildings remains very difficult due to the sector’s heterogeneity. To achieve ES in the building stock, Bierwirth and Thomas recognise the need for new radical policy approaches (e.g. a cap on average floor area per person). Still, they also suggest that some existing EE instruments may be adapted to support ES linked to equipment and use. Examples include financial incentives and providing energy advice.

Table 1

Energy sufficiency (ES) in buildings: area, action and unit of measurement

| AREA | ES ACTIONS | UNIT OF MEASUREMENT |

|---|---|---|

| Space |

| m2/cap rooms/cap |

| Design and construction |

| Yes/no |

| Equipment |

| n, kW |

| Use |

| °C Operational hours |

[i] Note: aClosing windows while heating or cooling a room or a building, shock ventilation with short-term wide window-opening instead of long-term tilting.

Source: Adapted from Bierwirth & Thomas (2019a).

Hu et al. (2023: 3) discussed the concept of building energy sufficiency, which refers to ‘building-related services that are provided in an equitable, reasonable, and ecological manner’. They listed three primary building services to which ES can be applied: space, activity (e.g. appliances) and a comfortable indoor environment. They adopted an occupant-centric approach that considered the building’s occupancy level in time and space, the heterogeneous requirements on quality and quantity (e.g. individual thermal comfort), and the ability to control and adjust the indoor environment (e.g. opening windows). Using these demand features, it can be argued that ES measures have great potential to reduce energy use. On the other hand, Toulouse & Attali (2018) focused on ES in appliances and their use in residential and non-residential buildings: the measures included more moderate usage, more reasonable sizing, substitution by a low-energy alternative solution (e.g. hanging laundry instead of using a dryer), sharing appliances and reducing ownership. For an average household and an office, they estimated a substantial savings potential of 50% on the energy used by appliances, from heating, ventilation and air-conditioning (HVAC) system products to household appliances to electronic products such as displays and servers. Toulouse and Attali also highlighted barriers to implementing these ES measures, especially societies’ dominant social norms and consumption culture.

It can be concluded that research on ES is biased towards the household sector (Toulouse et al. 2019) and that quantitative analysis of ES measures and appropriate approaches to accelerate their implementation is still scarce (Hu et al. 2023).

This research attempts to close these gaps by addressing ES measures in non-residential buildings, focusing on buildings used mainly by small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The specific focus is on the operational phase of the buildings, meaning the use of the energy services and the equipment inside the building. Moreover, this paper hypothesises that integrating ES measures in energy audits carried out in non-residential buildings could help accelerate their dissemination. It also discusses the feasibility, challenges and opportunities for the actors involved. The rationale for formulating this hypothesis emanates from the following three observations:

According to Bierwirth & Thomas (2019a), tailored ES advice can be more effective than general information campaigns addressed to end-users of their options. They also argued that ES advice should be integrated with advice on EE options for cost-effectiveness reasons, which generally happens during energy audits.

While studying the Swiss energy auditing programme PEIK (Swiss Federal Office of Energy 2017), the present authors observed a practice of a few auditors who enquire about the occupancy level of the site and the use of information technology (IT) and other equipment to suggest ES measures (without categorising them as such). Putting forward these measures can help generalise this practice among more auditors and more energy programmes. For a brief description of this programme, see Appendix 1 in the supplemental data online.

Energy audits are well-established programmes with which companies are familiar.1 Moreover, audits use standardised tools to evaluate energy savings. The dissemination of ES measures can benefit from these features.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 defines the ES measures in this study. Section 3 describes the methodology applied to conduct the research and test the hypothesis outlined above. Section 4 presents the main results. Sections 5 and 6 discuss the results and conclude.

2. Defining es measures

Based on Bierwirth & Thomas (2019a), ES measures are defined here as measures that reduce energy demand by changing the quantity or quality of the energy services demanded in a lasting way and not below people’s basic needs via occupant behaviour change, infrastructure change, and manual or automatic management of operation time to levels that match the demand.

From the above, two nuanced definitions of ES can be derived depending on what constitutes an energy service. The first definition, ES-stringent, interprets energy services strictly as the physical benefit utilised by end-users, emphasising that only savings on actively used energy align with ES. Consequently, measures such as reducing ventilation in an unoccupied space in a building at night are not categorised as sufficiency measures because they aim to eliminate energy use for an energy service that is not being utilised. This definition also includes ES measures that require a conscious decision or action by the user in contrast to automatic management of energy use and considers the deliberate effort to reduce energy use (e.g. turning off lights).

The second definition adopts a broader perspective. Referred to as ES-broad, it considers that the avoidance of an energy service that is anyway not used is also a sufficiency measure. From this angle, reducing ventilation in an unoccupied space in a building at night (outside working hours) is considered a sufficiency measure.

Both viewpoints will be discussed, and ES measures aiming at optimising active energy use (according to ES-stringent) or preventing unnecessary energy use (according to ES-broad) will be considered and compared.

In addition, some measures that have, up to now, been considered EE by ‘good housekeeping’ or efficient behaviour also fall into these definitions, such as installing presence detectors (ES-broad) and manually turning off lights (ES-stringent). Other measures fall into a grey area between EE and ES, such as optimising the operation of a heating system that was previously incorrectly tuned. Table 2 provides some examples to illustrate these differences.

Table 2

Energy saving measures according to energy sufficiency (ES)-stringent, ES-broad and energy efficiency (EE)

| MEASURE | ES | EE (AS DEFINED UNTIL NOW) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ES-STRINGENT | ES-BROAD | ||

| Reducing energy demand by avoiding or reducing an energy service following prescribed standard values (as defined in norms) (e.g. reducing the heating temperature, reducing the number of light bulbs in a corridor) | × | × | |

| Reducing energy demand by avoiding or reducing an energy service beyond the standard levels (e.g. reducing heating temperature, reducing the number of light bulbs in a corridor) | × | × | |

| Reducing energy demand automatically by avoiding or reducing an energy service that provides no physical benefit (e.g. automatically turning off lights in unused corridors at night) | × | × (EE through smart control) | |

| Reducing demand manually for an energy service that provides no physical benefit (e.g. manually turning off lights when leaving a room) | × | × | × (EE behaviour) |

| Reducing energy demand by reducing process capacity or size to meet real needs (e.g. reducing cooling zone area to minimise the duration of compressor use) | × | × | |

| Reducing energy use through corrective adjustments (e.g. tuning a previously misconfigured heating system) | × | × | |

Another aspect to consider is the notion of ‘reasonable’ energy consumption levels associated with ES, as highlighted in various studies (Bierwirth & Thomas 2019a; Hu et al. 2023; Toulouse & Gorge 2017). What is considered ‘reasonable’, however, may differ by culture (e.g. the reliance on cars in the US and widespread cycling in the Netherlands), by socio-economic factors (e.g. the diffusion of air-conditioning units in Africa as a result of rising purchasing power and living standards), and can change over time (e.g. owning a dryer versus relying solely on natural drying methods). Given the context of this paper is Switzerland, the authors will adhere to Swiss culture and refer to official Swiss legal standards, practices and norms to discuss ‘reasonable’ energy use.

The discussion of ES measures will focus on the primary energy services in non-residential buildings, including space heating, hot water, ventilation, air-conditioning, lighting and electric appliances.

3. Methodology

Three methods were used to conduct this research: semi-structured interviews, a quantitative analysis of ES measures and a questionnaire addressed to SMEs.

Semi-structured interviews of experts

Nine experts from various backgrounds (researchers, policymakers, organisations and energy advisors) were interviewed. This approach was used to obtain insights about ES in non-residential buildings, for which little information exists in the literature. These interviews were conducted to gather real-world examples and discuss practical considerations crucial for understanding how to integrate ES measures into energy audits effectively. Moreover, the hypothesis of integrating ES measures into energy audits to promote their dissemination was confirmed by some and challenged or expanded upon by others. This method is further detailed in Appendix 2 in the supplemental data online by describing the approach, the data collection and analysis tools, and the main questions that guided the interviews.

Quantitative analysis

A total of 297 measures were examined. These were proposed by some energy auditors in the Swiss EE audit programme PEIK that align with the principles of ES introduced by Bierwirth & Thomas (2019a), Hu et al. (2023) and Toulouse & Attali (2018) and the definitions provided in Section 2, though not categorised as sufficiency measures in the audits. Measures that address sufficiency in four end-use categories (heating and hot water, air-conditioning, ventilation, and lighting) were extracted using either the existing classification or a list of selected keywords to scan textual descriptions of all measures in the database. These keywords, in French, German and Italian, are reflective of the nature of ES measures aiming to reduce the demand. The focus is on the end-use categories (heating and hot water, air-conditioning, ventilation, and lighting) because these are generic, and the associated measures can be reproduced on a large scale. In addition, drawing from the PEIK database, examples of four ES measures are presented that relate to various equipment and appliances. The database provides ex-ante estimates of the payback time and energy savings. Cost-effectiveness2 and energy savings in relative terms (%) are then calculated for each measure. Having access to datasets of some ES measures from an established energy audit programme is a unique opportunity for research on ES. The objective is to shed light on examples of ES measures that could be applied at a large scale in non-residential buildings and to examine their impact and profitability.

Questionnaire addressed to SMEs

To evaluate the acceptance and feasibility of ES measures within the SMEs and to identify the main barriers to implementing ES measures identified by the interviewed experts (see above), a structured questionnaire was developed according to the literature on best practices for survey research (Draugalis et al. 2008; Fowler 2013). The questionnaire was disseminated to 108 SMEs in the Swiss Canton of Geneva that had participated in a PEIK energy audit. The questionnaire consisted of two parts. The first presented a set of ES measures (summarised in Appendix 4 in the supplemental data online), and the respondents were asked to rate each of them in terms of acceptance and feasibility using a Likert scale. Later, the respondents were given a list of potential barriers to implementing ES measures and asked to rank them by order of importance.

4. Results

4.1 Semi-structured interviews results

This section presents the results of the interviews with the experts (researchers, policymakers, organisations and energy advisors). The interviews were initiated by discussing the concept of ES, revealing various interpretations around the notion of comfort and the distinction between ES and EE. These diverse viewpoints are presented in Appendix 5 in the supplemental data online. The application of ES within companies and the specific context of energy audits are presented below.

4.1.1 Barriers to ES in SMEs and some potential solutions

Most experts agree that the term ‘sufficiency’ has a negative connotation, meaning ‘there is this wariness about sufficiency’ (D9). At the individual level, the term is linked to the constraint of personal freedom, and at a societal level:

sufficiency is considered to be a constraint to infinite growth and the economy; it goes against the mainstream thinking.

(D13)

While some explain this reluctance by a lack of knowledge (‘the concept is unknown for the majority of people’; D10), experts who work with companies admit avoiding using the word ‘because it is politically charged and will put people off’ (D17). They point out that they ‘talk more about demand reduction’ (D17) and that:

because if we start explaining the concept, it’s going to take very long, we organise it in a way that it is much more practical.

(D1)

Lack of resources is another barrier to ES measures in companies. This is reminiscent of the barrier faced by EE, which is still being studied and remains relevant. For some, ‘providing the needed time and resources is essential’ (D1) for successful implementation of ES. However, some SMEs:

usually don’t have the capacities or the resources to always stay up to date or to introduce additional solutions.

(D12)

For EE, programmes supporting the implementation of the measures are in place to provide technical and financial support. A similar system can be applied for ES:

this is probably what an audit also has to provide: solutions, good practices and to connect them with other companies that successfully implemented such measures.

(D12)

Barriers to implementing ES measures can also be technical, stemming from infrastructure limitations such as a lack of control systems that would allow adjustments of temperature settings in real time based on occupancy or old HVAC systems that do not support dynamic scheduling. Another significant barrier is the lack of individual metering for companies in multi-tenant buildings. These entities are not incentivised to implement ES measures to save thermal energy because it will not be reflected in their thermal energy bill.

Similarly, issues of responsibility and knowledge can also hinder the implementation of ES measures. According to one expert:

there might be useless ventilation running at night. […] The solution seems simple because they just need to switch the ventilation off at night. However, no one knows how to fix it or who’s responsible for it.

(D13)

The lack of willingness or the resistance of the top management is also linked to human factors and is again reminiscent of EE barriers. This barrier could be more critical in ES than EE because the former is ‘linked to personal lifestyle, our values, beliefs and culture’ (D11). Support from management is crucial for adopting ES measures because it can ‘influence the company’s culture tacitly or explicitly’ (D11). For example, measures of shutting down heating and ventilation where it is unnecessary:

could need reorganising the spaces accordingly, and this reorganisation has to come from the top.

(D14)

Experts who work with companies also stress the importance of employee involvement. They encourage establishing communication with the staff that ‘needs to understand why this is being done, it’s key’ and that ‘if they understand it will be much easier to implement’ (D13). A practical example for reducing heating temperatures is:

starting from the principle that if the majority does not accept it, it will not last over time. So, find a way of making it convincing and of ensuring that they do not perceive any thermal discomfort.

(D17)

The same expert mentions anecdotal advice to the staff to ‘learn to move around at work, go see people and do stand-up meetings’ (D17).

Another barrier, and one of the most discussed, is the difficulty quantifying the energy savings related to some ES measures. This difficulty arises from a lack of data and the necessity of making numerous assumptions to estimate the impact of these measures. Some argue that:

focusing on quantifying is a wrong approach because the energy savings are only co-benefits of ES.

(D10)

Others fear that ‘an overemphasis on quantifying everything could dilute the essence of sufficiency’ but still think that ‘if we don’t quantify the costs and savings, maybe nothing changes’ (D13). On the other hand, most experts seem ready to pursue quantification methods at least:

in the cases where it can be quantified such as the reduced time of use of appliances

(D15)

and see it as one of the main incentives for companies which:

don’t know the benefits, so we need to show them the numbers exactly like for EE. It’s based on a lot of assumptions, but it still could work.

(D9)

4.1.2 Drivers of ES in SMEs

According to the experts, the driver that could push SMEs towards implementing ES measures is, first and foremost, an economic one. Energy cost reduction is ‘the first benefit, and everyone will be happy with it’ (D1). The second driver is linked to the current and future energy crises that add urgency for SMEs to anticipate energy shortages, higher energy prices and constraints on energy use. As one expert put it:

if they do not go through the measures now, there will be one day when they cannot make the decision anymore.

(D9)

SMEs can also be interested in enhancing their attractiveness to customers ‘by signalling to be an ecologically aware business’ (D12) and to staff by:

contributing to reducing their climate impact, which can be very meaningful and a good motivation for them

(D13)

and to potential employees and ‘particularly young talent, who are taking this more and more seriously’ (D17).

Another significant driver is the increasingly environmentally conscious market, certifications and labels. Large companies with environmental obligations that request offers from SMEs can ask questions about sustainability because it is linked to their ‘scope three’ of CO2 emission accounting (GHG Protocol 2011). ‘To be able to submit bids, these SMEs have to be in line with sustainability’ (D14, D17). A policymaker stated that:

companies are currently interested in what we call CSR, corporate social and environmental responsibility. It’s a certification that includes a series of aspects. In the energy sector, we want to include sufficiency.

(D14)

The implementation of an environmental, social and governance (ESG) strategy, including corporate social responsibility (CSR) targets, is increasingly popular among SMEs. This can drive the company to organise itself better to reach these targets and can lead to a shift in values, habits or traditions within the company. This change often stems from a comprehensive review triggered by the implementation of sustainability practices, requiring the engagement of both management and employees.

4.1.3 ES measures in energy audits

The interviewed experts were then introduced to the idea of integrating ES measures in energy audits. Different opinions were expressed about the opportunities, risks and other aspects related to energy auditors.

As regards the opportunities of including ES measures in energy audits, one advantage of energy audits that was put forward is that they are a good tool to ‘assess the situation and [to] provide information’ (D1, D9), because without a clear assessment, it is difficult for SMEs to implement the right measures. Moreover, the ‘wide-ranging examination of the site’ conducted in energy audits makes it ‘a robust tool to get quick results’ (D14). Standard practices of energy audits, such as checking thermostat settings, can identify ES opportunities and provide immediate feedback on potential improvements.

One policymaker was also concerned about the overwhelming number of environment-related programmes targeting companies, especially SMEs. They argued that:

we can’t create another new programme for businesses. They already have people who go to see them about energy, biodiversity, waste, and so on. It exhausts them. So, it’s essential to stay with an approach they’re already comfortable with and develop it further to include ES measures.

(D14)

In addition, this strategy can help portray ES measures not as an additional burden but as an integral part of a company’s continuous efforts to save energy.

Explicitly including ES measures along with EE measures is not entirely new. One expert stated that:

the French Standardisation Organisation is looking to include sufficiency aspects in the energy management standards.

(D13)

The same expert stated that ES measures are also included in another programme targeting municipalities awarded with energy labels.

Some interviewees also highlighted risks, especially the limited scope of an energy audit in comparison with the vast aspects of companies’ activities to which ES can be applied, such as:

what kind of products they are offering and how these products are produced, maybe the big issues are there.

(D12)

During the interviews, it was challenging to make some experts narrow down from the broad concept of sufficiency to ES within the companies’ working spaces.

Another concern highlighted is the non-mandatory nature of implementing the measures proposed in energy audits (in most cases).

Energy audits in the European Union are mandatory, but it’s not mandatory to implement the measures

(D10)

which increases the risk of ‘audit reports sitting in the drawer’ (D15). Another risk is that ES measures, if unsuitable for the company’s unique context, may not be fully understood or embraced by the company. This leads to an increasing probability of lack of implementation. One expert suggested:

reading the business culture and going into a direction tailored to the company and resonating with the company.

(D11)

4.1.4 Role of energy auditors

Integrating ES measures in energy audits introduces several challenges for energy auditors. It can consequently lead to resistance from their side, as expressed by one expert: ‘They will say: this is new, and we do not have the time’ (D14). The reason for the resistance may be that some types of ES measures go beyond the core competencies of auditors. They will ‘need to enlarge their catalogue with new ES solutions’ (D12). In addition, they are the ones challenged with quantifying energy savings from ES measures: ‘They need to quantify ES measures in terms of energy and financial savings to be convincing’ (D12).

Moreover, different auditors have different approaches. Some strictly adhere to the guidelines provided by the programme, while others are more creative or have more experience. This variability indicates that ‘clear guidelines are needed’ (D13). A standard checklist of what they need to consider should be provided:

a few rough entry points so that they can select in the auditing tool measures like ‘sufficiency in heating’ or ‘sufficiency in appliance use’ to help them start’.

(D14)

The possibility for more creative recommendations based on their observations should also be encouraged, especially since ES opportunities can differ from one company to another.

There is an opportunity for auditors to acknowledge their limitations and establish relationships with specialists, mainly if the ES measure entails an organisational change (e.g. space use). One expert pointed out:

We are engineers, but we are starting to work with sociologists and psychologists because they know how to work on that (change management).

(D14)

According to them:

auditors are not going to be ES masters, but they are going to discover opportunities of ES. If there is a need, the theme can be explored in greater depth by external specialists.

(D14)

4.2 ES measures in the peik database

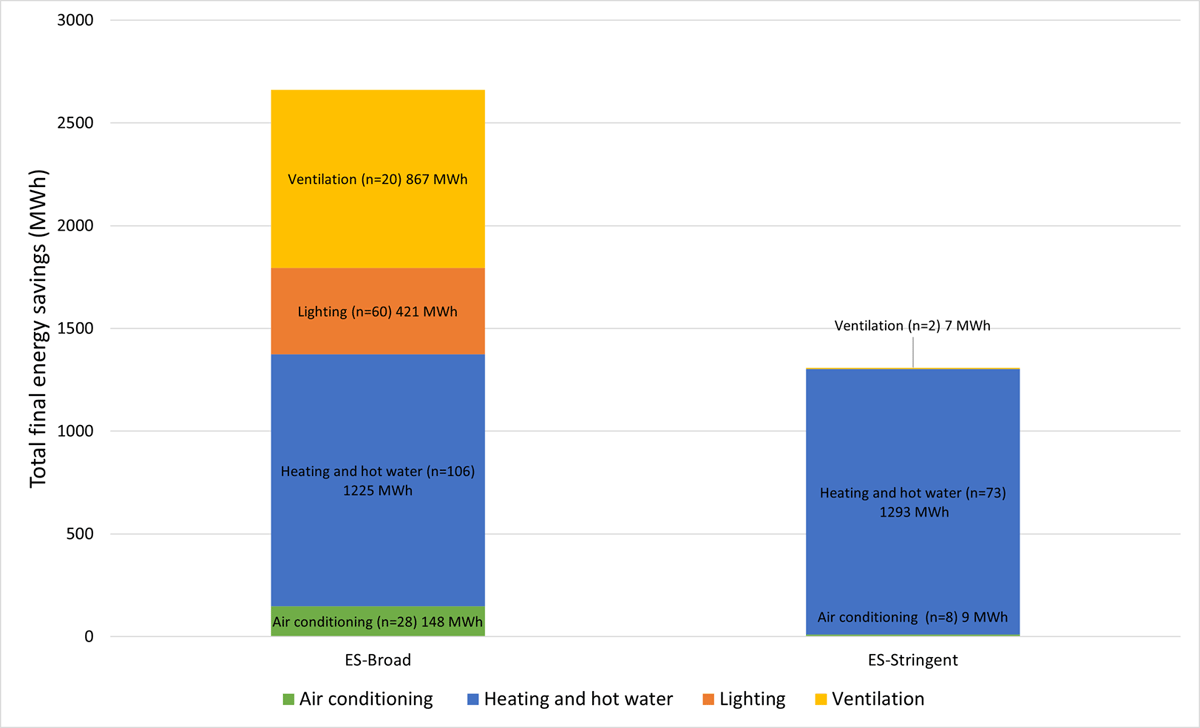

ES measures corresponding to both definitions introduced in Section 2 were extracted from the PEIK audit database. They represented 6% of all the identified measures and nearly 4% in terms of saved final energy, a low proportion that underscores the scarcity of ES measures. A total of 28% of these measures fell into the ES-stringent definition, and they merely represented 1.7% of all the measures in PEIK database. In ES-broad, most ES measures were related to heating and hot water (60%), and 20% were related to lighting. The rest of the measures were divided between air-conditioning and ventilation, with shares of 12% and 7%, respectively. Figure 1 shows the total estimated energy savings achieved through the measures: heating and hot water account for most of the savings, followed by ventilation measures, despite being the smallest category in terms of number. Air-conditioning measures have the least savings. In ES-stringent, lighting measures disappear, and only two ventilation measures and eight air-conditioning measures correspond to this restricted definition. Heating and hot water measures represent the majority in terms of number and savings. Appendix 6 in the supplemental data online presents more detailed descriptive statistics of ES measures by category for ES-broad and ES-stringent.

Figure 1

Total final energy savings by end-use categories and according to the two definitions (n = 279).

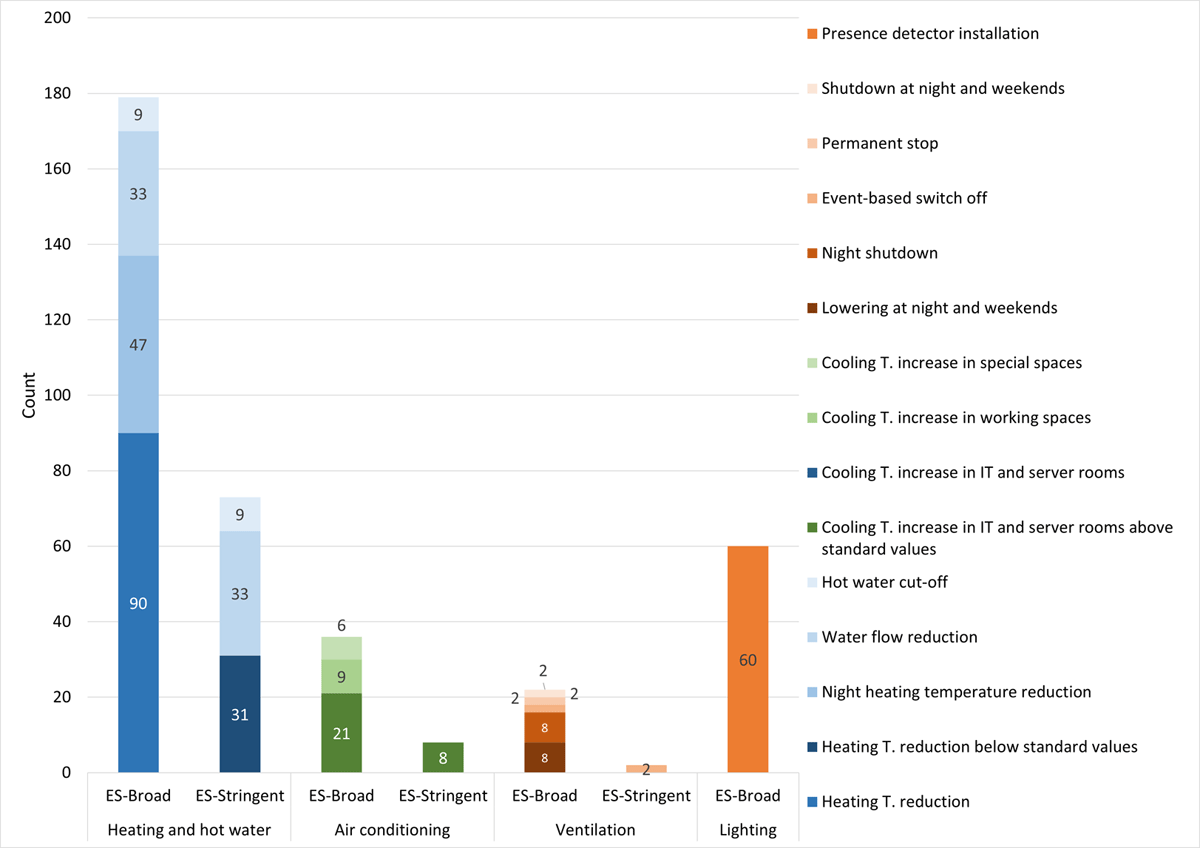

The ES measures were then further categorised into further types describing the concrete actions (Figure 2) according to the two definitions (ES-broad and ES-stringent). Only three ES types in heating and hot water are included in ES-stringent: a part of heating temperature reduction measures that go below the standard values, water flow reduction and hot water cut-off measures. Similarly, for air-conditioning, only eight measures of cooling temperature reduction in IT and server rooms are found to go beyond the standard values and are consequently counted as ES-stringent measures. Ventilation measures in ES-broad are presented by an equal distribution between ventilation lowering at night and weekend and night shutdown measures, which constitute the majority in this category, and only two measures of event-based shutdown of ventilation (e.g. ventilation monobloc stops in the event of opening the doors) correspond to the definition ES-stringent. Lighting shows one dominant ES measure exclusive to actions of installing presence detectors (ES-broad).

Figure 2

Types of energy sufficiency (ES) measures by end-use category (n = 297).

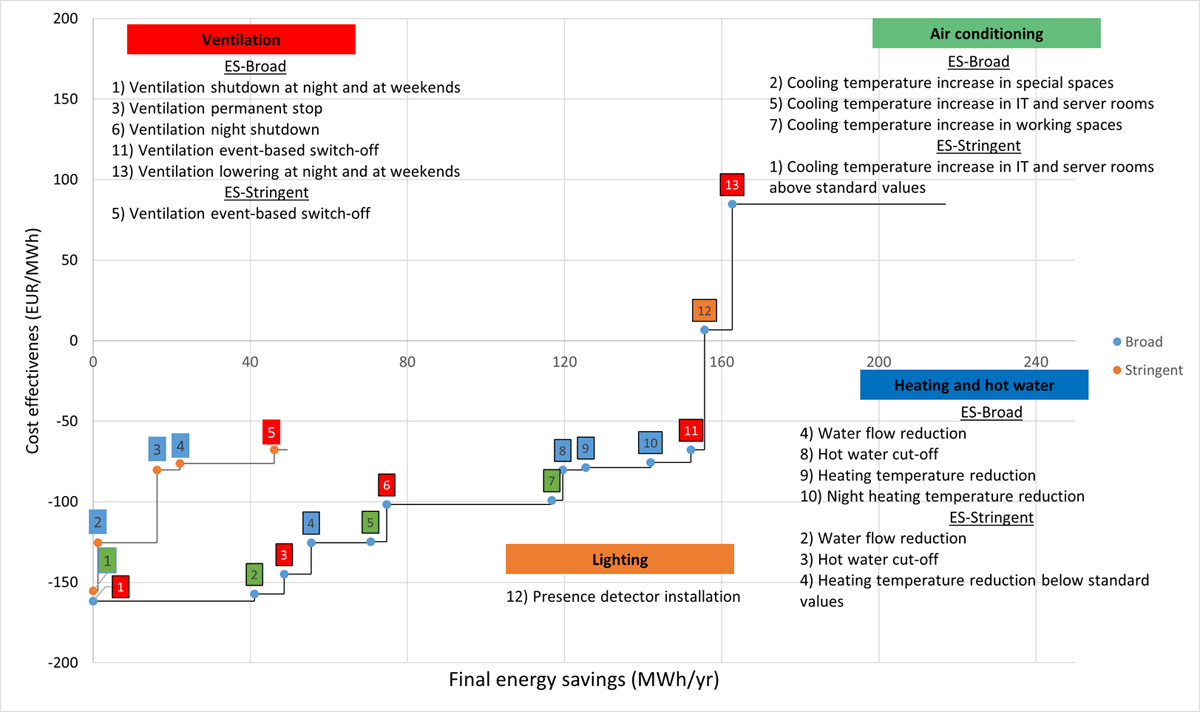

Figure 3 shows the cost curves of the ES measure types according to ES-broad and ES-stringent, respectively.

Figure 3

Energy cost-curve of energy sufficiency (ES) measures according to ES-broad and ES-stringent (n = 297).

Note: Cost curves show the ES measures’ cost-effectiveness (y-axis) as a function of the energy savings (x-axis).

For the definition of ES-broad, ventilation shutdown at night and the weekends is the most cost-effective ES measure. This measure and two other ventilation measures (ventilation night shutdown and ventilation lowering at night and at weekends) offer the largest energy savings among all ES measures (Figure 3, horizontal steps 1, 6 and 13). However, this last measure (13) is the least cost-effective across all categories. Ventilation permanent stop and night shutdown present weaker savings but are still cost-effective (Figure 3, 3 and 11). Measures implying a higher cooling temperature are cost-effective, with lower average energy savings than ventilation measures. Cooling temperature increase in special spaces presents the highest energy savings in this category and is the most cost-effective (2), followed by cooling temperature increase in IT and server rooms (5) and, lastly, cooling temperature increase in working spaces (7).

Only for one measure in the heating and hot water category does cost-effectiveness exceed –€100/MWh, i.e. the water flow reduction measure (4). The other three measures in this category show a similar cost-effectiveness (between –€80 and –€75/MWh), but various degrees of energy savings, with heating temperature reduction measures (9) showing the highest energy savings and hot water cut-off showing the lowest. Installing a presence detector (after implementing energy-efficient lighting) does not seem cost-effective, and the energy savings achieved through this measure are mediocre (12).

Figure 3 also shows the cost-curve of the five ES measures per the definition of ES-stringent. The total average energy savings estimated for these measures represents 20% of the energy savings estimated for all ES-broad measures. While the measures offering the highest energy savings are not included, all measures are cost-effective. The measures with the highest savings belong to heating and hot water (heating temperature reduction below standard values (4) and water flow reduction (2)), and the measures with the least energy savings are ventilation event-based switch off (5) and cooling temperature increase in IT and server rooms above standard values (1).

In addition to these measures, equipment and appliances used in SMEs can also be subject to ES measures. However, they were not included in the above analysis because of their scarcity, context-related specificities and lack of data. Table 3 provides an overview of various ES measures targeting equipment and appliances, with descriptions, examples and their potential impact as estimated by the auditors. Coffee machines, for instance, found in almost all SMEs, regardless of the sector, often remain on standby and can benefit from timers to minimise final energy use outside of working hours. The example shows a 10% energy saving and a payback time of just 0.6 years. Similarly, kitchen equipment in the catering sector, such as plate-warmers, can be operated more sufficiently by aligning their usage with actual service times, yielding significant energy reductions of up to 50% with an immediate payback. Video-conferencing equipment saves energy related to travel, but it is often left on standby. Turning off monitors post-use is a behavioural change measure that can save up to 50% of final energy. Lastly, investigating the energy-use patterns can put forward a permanent night band indicating constant energy use during the night. Going after the sources of this energy use can save between 15% and 20%, depending on the width of the band. The payback period will vary depending on the specific measures implemented. These additional measures emphasise that ES can be achieved through simple adjustments.

Table 3

Additional energy sufficiency (ES) measures addressing equipment and appliances with descriptions, examples and their impact estimated by the auditors

| ES MEASURES ADDRESSING … | DESCRIPTION | EXAMPLE | FINAL ENERGY SAVINGS RELATIVE TO FINAL ENERGY USE BEFORE THE MEASURE (%) | PAYBACK TIME (YEARS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coffee machines | Coffee machines often stay on standby between uses and at night. Install a timer to set the machine’s automatic switch-off time | Use a timer to switch off the machine at night and outside working hours all year. Standby power is 100 W; time outside working hours is 4680 h; savings: 468 kWh/year | 10% | 0.6 |

| Kitchen equipment | Some kitchen equipment, such as ovens and plate-warmers, are turned on long before the effective period of use | Instead of 12 h/day, the plate-warmers are only switched on during lunch and dinner service time; saving: 6 h/day | 50% | 0 |

| Video-conferencing equipment | Electronics located in video-conferencing rooms are permanently on standby | Raise awareness of turning off monitors after a session | 50% | 0 |

| Final energy use night band | Important baseloads at night are noticed in some SMEs’ final energy use measurements | The main factors behind this baseload can be appliances on standby (computers, printers, coffee machines, etc.) and uncontrolled ventilation and process-cooling equipment | 15–20% | Case-specific |

[i] Note: SMEs, small and medium-sized enterprises.

4.3 Questionnaire to SMEs

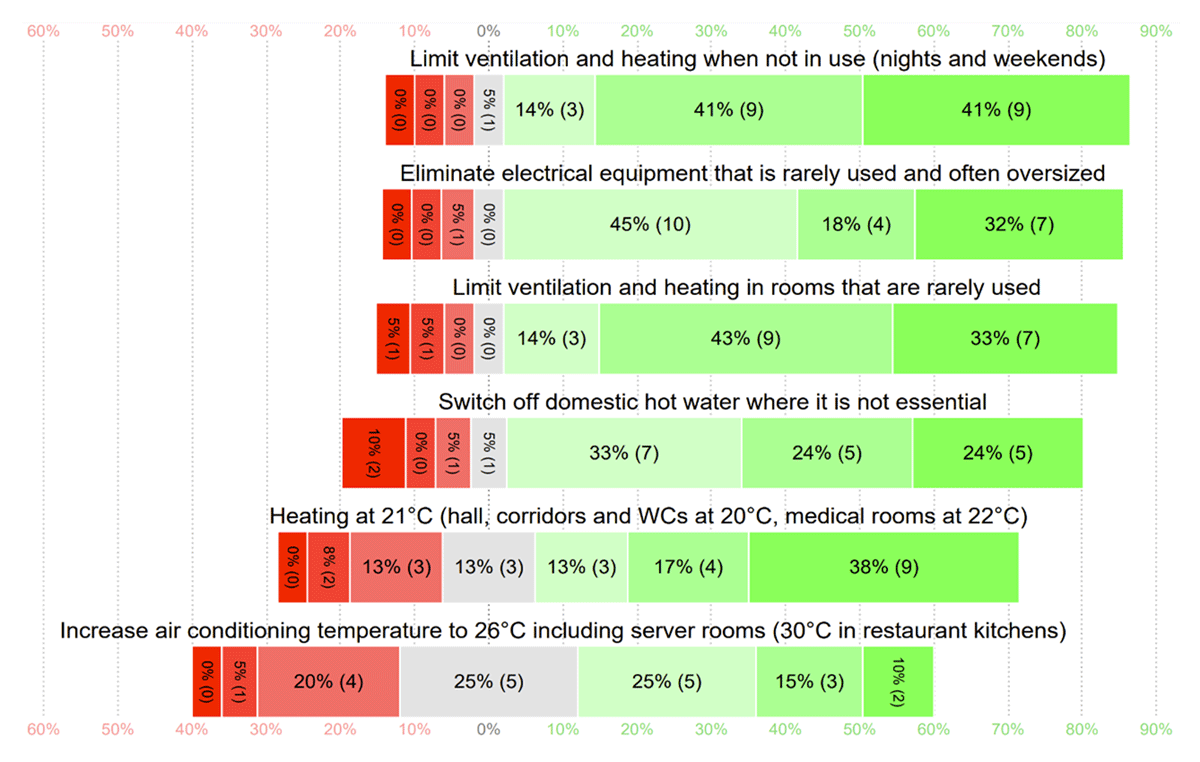

This section presents the results of the questionnaire completed by 20 SMEs in different sectors: seven office-based, nine in catering, three in manufacturing and one in another sector. Figure 4 illustrates the SMEs’ responses regarding their acceptance of the ES measures, rated on a Likert scale: the scale ranges from ‘not applicable’ to ‘already implemented’, with varying degrees of favourability in between. For measures categorised under ES-broad, a large portion of the SMEs attest to having implemented these measures, notably limiting ventilation and heating when not in use and reducing heating to 21°C. While over half the respondents scale as somewhat favourable and very favourable to the first four measures, measures suggesting limited temperature settings, whether for heating or cooling, tend to have a more diverse range of responses, with some participants perceiving them as unfavourable, implying that comfort levels may play a significant role in the acceptance of these ES measures. A total of 40% of the respondents who view these temperature limitations unfavourably are from the catering service sector, particularly within retirement homes, followed by offices. Manufacturing SMEs, on the other hand, seem to be the least demanding in terms of indoor conditions, showing greater flexibility in accepting temperature limitations.

Figure 4

Acceptability of energy sufficiency (ES) measures according to the small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (n = 20).

Regarding the measures that fall into the ES-stringent definition, Figure 4 indicates that SMEs are generally in favour of or have already implemented measures such as sharing equipment and managing natural light and ventilation. However, as mentioned above, they are more divided on measures that directly impact the thermal comfort of their premises, where 25% consider the increase of air-conditioning temperature to 26.5°C somewhat unfavourable, and 35% consider the heating at 19°C somewhat unfavourable to very unfavourable. The acceptance by the sector follows the same pattern described above, with the catering service being the least flexible, followed by offices and, finally, manufacturing SMEs, which seem to be the most open to these measures.

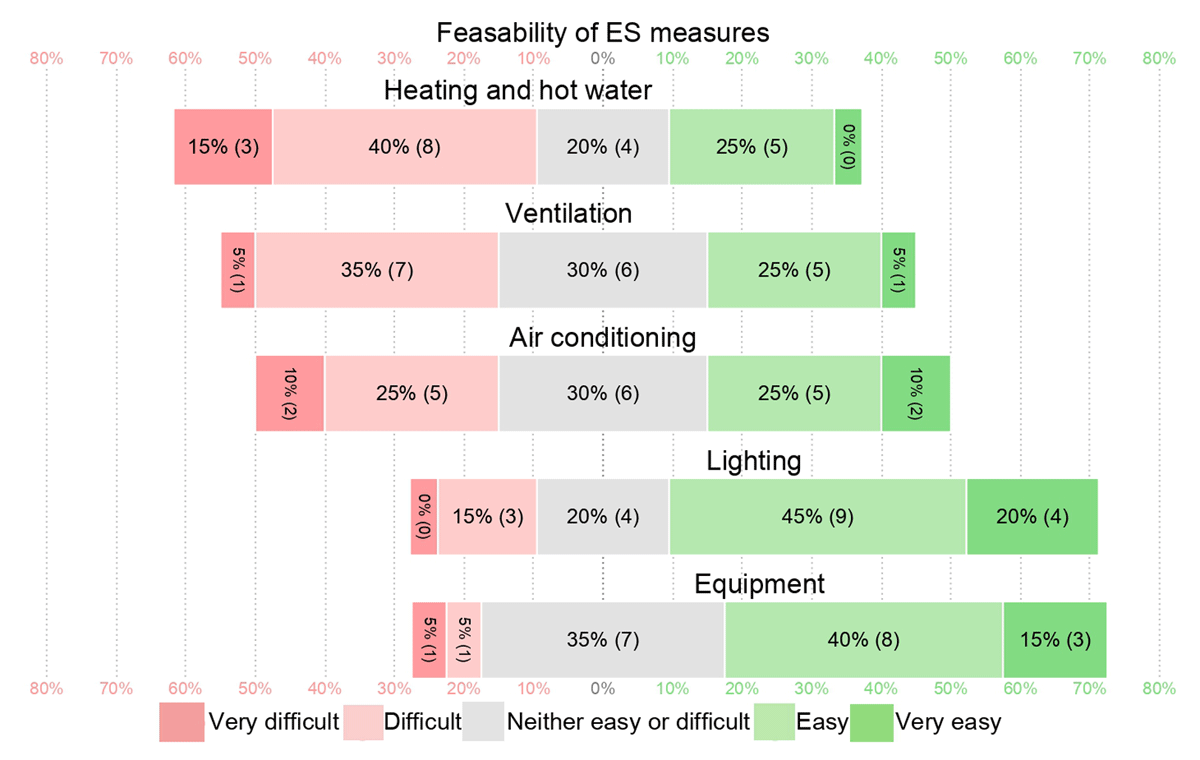

This is somehow reflected in the SMEs’ responses to how feasible are the ES measures grouped by the end-use category (Figure 5). Heating and hot water measures are seen as difficult to very difficult for over half of the respondents. A general trend suggests that SMEs find lighting and equipment measures more feasible to implement than those related to air-conditioning, ventilation, heating and hot water. The spread of the answers across the Likert scale for these measures also underscores the diversity among the SMEs.

Figure 5

Feasibility of energy sufficiency (ES) measures according to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (n = 20).

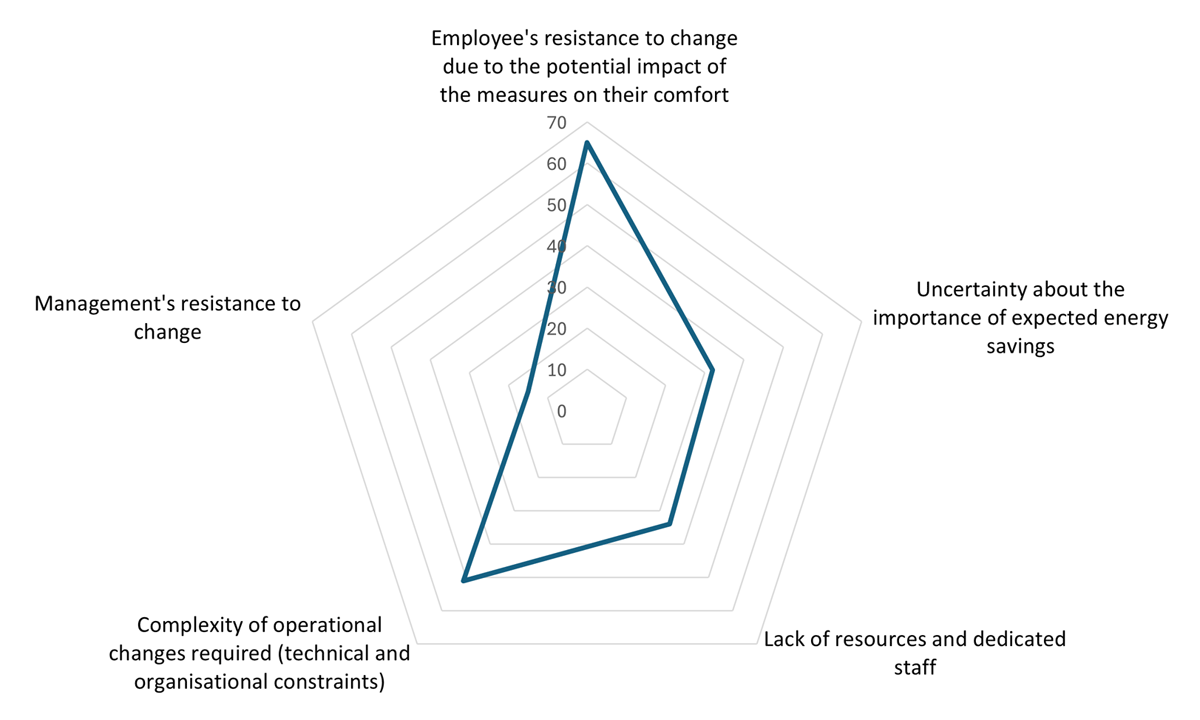

Figure 6 illustrates the ranking of barriers to implementing ES measures as perceived by the SMEs. The highest-ranked3 barrier is the complexity of operational changes required (technical or organisational), followed by the employees’ resistance to change due to the potential impact of the measures on their comfort. Both barriers underscore two different features that SMEs consider when facing an ES measure: the practical and technical aspects, as well as the human aspect. The uncertainty about the importance of expected energy savings is ranked as the third most significant barrier, which reflects some scepticism or lack of information about the actual benefits that ES measures may yield. Management resistance to change seems to be a less significant barrier, which is expected given that the participating SMEs are already involved in or have completed an energy audit and can be considered progressive.

Figure 6

The ranking of barriers to implementing energy sufficiency (ES) measures according to the small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (n = 19).

5. Discussion

Two definitions of ES are used depending on whether the energy service is considered to offer an essential benefit and how important is the effort involved in the ES measure: ES-broad and ES-stringent. This distinction is important to reconcile the different views of ES and show that ES opportunities can be implemented by end-users with different capabilities, resources and commitments. ES-broad can be understood as avoiding obvious energy waste. Measures in line with this definition can be applied relatively easily and without significant behavioural changes from the end-users, while ES-stringent targets more deliberate actions and possibly more significant lifestyle changes (e.g. reducing heating temperatures beyond the standard values).

The barriers associated with ES implementation (being ES-broad or ES-stringent) show interesting parallels with those commonly discussed in the literature related to EE, but partly also contrast with them. Barriers to ES that are directly aligned with those encountered in EE include the lack of resources, technical and infrastructural limitations, and possible resistance from management. However, two distinctive barriers that seem to set ES apart from EE are its negative connotation and the challenge of quantifying its benefits. The negative connotation associated with ES most probably stems from the perception that this concept encompasses loss in comfort, welfare and utility (Toulouse et al. 2019; World Resources Forum 2023).

EE, on the other hand, is more commonly linked to productivity improvements and prosperity (Virkki-Hatakka et al. 2013; Wubben 2000), where the focus is on doing more with less and reducing energy costs while maintaining or enhancing output levels. This framing of EE is more compatible with the current growth-oriented social norms. In this logic, overcoming the negative connotation of ES would then require a shift to social norms that promote ‘living well with less’ (Figge et al. 2014). Aware of this huge task, some advocates of ES measures among the interviewees take a shortcut by avoiding using the term ‘ES’ when communicating with companies and instead opt for ‘energy savings measures’ or ‘EE behaviour’. Others choose to reframe ES as an essential component of organisational resilience by emphasising its potential to reduce vulnerability to energy price volatility and contribute to environmental sustainability. This suggests that policymakers and programme designers should be aware of this negative connotation associated with ES and should make the choice of either keeping ES ‘low-key’ (i.e. to represent ES measures by more widely accepted labels or combining them with EE measures) or explicitly expressing the necessity of limiting the needs, aiming to initiate reflection about more fundamental changes in societal values and norms. The latter could involve large educational campaigns to shift public perception and to link ES not to loss of comfort but to positive outcomes such as health and a more equitable distribution of resources.

In accordance with the first approach, quantifying ES benefits in terms of energy and financial savings, even if complicated in some cases, is what most interviewed experts think of as a suitable approach to draw companies’ attention to ES measures and, according to some researchers (Bierwirth & Thomas 2019b; Toulouse & Gorge 2017), also policymakers’ attention. However, focusing on quantifying and documenting the impacts of energy-saving measures may hinder innovation within programmes and may involve efforts that are disproportionate compared with the accuracy of the estimated savings (Guibentif & Patel 2023). Moreover, emphasising the financial savings of ES to promote it contradicts its essence by shifting the attention of the end-user to what they can do with the saved money, nearly incentivising a rebound effect. Sorrell et al. (2020) discussed this topic in the context of ES measures and found a rebound effect of 5–15% for ES measures affecting heating and electricity, while higher values are found for ES measures in other sectors such as mobility (25–40%) or food (66–106%) (Sorrell et al. 2020). Moreover, the magnitude of the rebound effect depends on the end-user’s motivations, circumstances and choices. This means that a company with strong environmental values or that has inscribed the concept of ES in its culture (beyond the financial savings) is more likely to behave consistently between different aspects of its activity (e.g. energy use in building and product resourcing) and reinvest the savings in sustainable initiatives (e.g. installing photovoltaic panels or implementing smart electric vehicle charge points), thereby minimising the rebound effect.

The present study’s results show that energy-saving measures that can be categorised as ES measures in the PEIK database are still scarce. More ES measures would need to be defined, and they would need to be suggested by more auditors to be disseminated more widely among more SMEs. Some of these measures drive substantial energy savings, and most are cost-effective. Ventilation ES measures, including ventilation shutdown at night and weekends, ventilation night shutdown and ventilation lowering at night and weekends, offer the largest energy savings among all identified ES measures, followed by heating and hot water measures, notably water flow reduction and heating temperature reduction measures. The latter saves even more energy if the reduction goes beyond standard values. Considering these findings and in light of previous insights, it is clear that while cost-effectiveness can play a crucial role in promoting ES measures, they must be pursued and communicated carefully to avoid undermining the very essence of ES.

Energy audits were seen as effective tools for assessing situations, providing tailored information, identifying immediate ES opportunities and an efficient strategy to integrate ES measures without overwhelming companies with new programmes dedicated exclusively to ES. The limited scope of energy audits and the non-mandatory nature of implementing the identified measures are seen as potential risks. However, the use of auditing is not an end in itself; it is useful in triggering awareness, after which it is necessary to move on to other processes and other areas of ES, such as the ESG CSR process, for example.

Energy audits were studied as a method to disseminate ES measures, but some significant and potentially impactful ES measures that could be implemented in organisations may have been overlooked. For instance, sufficiency measures mentioned in the CLEVER scenario include the limitation of floor area by prohibiting the expansion of commercial areas and increasing home office (Bourgeois et al. 2023). In the mobility sector related to SMEs, teleconferencing as an alternative to travel can be encouraged, and changes in private travel habits can be incentivised. In the food sector, sustainable practices in cafeterias, such as local sourcing, offering vegetarian menus or reducing food waste, can be implemented. These are some examples where ES can be applied but do not fall into the scope of a standard energy audit and may require specific policies and incentives. Compared with the ES measures included in the PEIK database (largely representing ‘low-hanging fruits’), these examples are more demanding to implement and require the involvement of various actors from various fields of expertise. Moreover, they are likely to face more resistance and are tied to a more fundamental discussion around ‘needs and wants’ (Fawcett & Darby 2019).

The role of energy auditors is crucial. To integrate ES measures effectively and avoid resistance by the auditors, clear guidelines and a standard checklist for auditors are necessary, along with encouragement for creative recommendations based on observations. Additionally, it is important to establish clear communication with auditors, explicitly encouraging them to use the new guidelines to identify ES measures. Training programmes can be offered to help auditors understand the principles of ES and to identify related opportunities during audits. While auditors should not be expected to become experts in ES, they should be equipped with the necessary tools, including access to a network of experts to whom they can refer SMEs for further assistance. For example, auditors can collaborate with specialists in areas such as change management to address effectively the organisational changes required for implementing ES measures.

Programme managers can collaborate not only with auditors as ES promoters but also with IT support, architects, equipment installers and building managers to expand areas of ES guidance and ensure continuous implementation of ES measures. These actors should also be encouraged to consider the type of building users and their different needs and preferences. An external communication source working with companies reported that users were frustrated by the lack of control in a modern building (needing to hang a blanket on the window in the afternoon in a space used for childcare). An energy audit can be crucial in reporting these needs and advising the adaptation of floors and segments of the buildings according to the end-user’s diversified needs. Making end-users aware and controlling windows and HVAC terminals is proven to lead to energy savings (Hu et al. 2023). This approach is even more relevant in light of this study’s results regarding the acceptance of ES measures in companies which show the importance end-users allocate to their indoor environment, where there appears to be a trend that as the heating temperature setting decreases, the favourability towards the ES measure decreases, and the same for the cooling temperature setting increases. Moreover, answers on the feasibility of ES measures seem polarised regarding ES measures directly affecting the indoor environment and thermal comfort.

Building on these elements, it becomes clear that effective promotion of ES measures, progressive organisational culture and available control systems significantly contribute to the success of ES measures implementation in SMEs. The case of the commercial sector in Japan illustrates these principles, where efforts to save electricity after the Fukushima catastrophe, coupled with a strong and homogenous culture nationwide, along with building designs with intuitive placement of control systems, allowed the commercial sector in Japan to achieve a 6 GW drop in electricity demand every weekday during lunchtime (Meier & Bedir 2015). Other ES considerations in building design include maximising natural light and optimising building orientation; they can be integrated in sustainable building certificates—e.g. Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED), Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method (BREEAM), and Minergie—to enhance the effectiveness of energy-saving initiatives. Additionally, it seems crucial to integrate ES principles into building energy standards. While these policy instruments set efficiency requirements, they still allow consumption to increase with size (Bertoldi 2022). Building codes must become more progressive, ensuring that EE standards scale with the size of the building, and potentially setting absolute caps on maximum allowable energy consumption regardless of floor area. Such an approach ensures that larger buildings do not disproportionately contribute to increased energy demand.

6. Conclusions

To promote energy sufficiency (ES) measures among small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), a delicate balance must be struck between promoting financial benefits and fostering a deeper commitment to the concept of sufficiency. According to two nuanced definitions, two distinguished types of ES measures differ in the emphasis they give to the various ES measures to be implemented in SMEs with different capabilities and commitments. The hypothesis that integrating ES measures with energy efficiency (EE) measures in energy audits would present an effective way to start disseminating ES measures among SMEs is confirmed, and some associated risks, such as the limited scope of energy audits and the non-mandatory nature of the identified measures, are highlighted.

Auditors, who would play a pivotal role in identifying and communicating ES opportunities, will require standardisation, flexibility and collaboration with specialists. The findings on the varied ES measures, especially related to energy services such as ventilation, cooling, heating, hot water and lighting, can help auditors and energy managers prioritise the most energy-saving and inform companies about cost-effective ES opportunities. The results also emphasise the significant influence of end-users’ preferences about indoor conditions for the acceptance of ES measures, with a clear polarised pattern related to temperature settings in cooling and heating, impacting favourability towards ES initiatives that directly affect indoor environmental quality and thermal comfort. By setting out ES measures that are widely accepted, experience can be gained to subsequently aim for more stringent measures that are closer to the essence of sufficiency.

Notes

[3] The companies studied in this paper are primarily SMEs, as PEIK audits and the questionnaire are specifically targeted at this group. Throughout, the terms ‘companies’ and ‘SMEs’ are used interchangeably.

[4] Cost-effectiveness or levelised cost of saved energy is calculated using:

The annuity factor is calculated using an assumed discount rate of 10%:

[5] Weights from 1 to 5 were assigned to the five ranks. These weights were multiplied by the response counts for each answer in each rank. The average rank for each answer choice is then the weighted sum. The highest rank is 80, calculated by the multiplication of the top score (5) by the total number of answers. The minimum is 46, calculated by the multiplication of the lowest score (1) by the total number of answers.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Gisela Branco of the Geneva Canton Energy Agency for support through insightful exchanges on the topic. They also thank team éco-21 of the Services Industriels de Genève (SIG) for sending the questionnaire to small and medium-sized enterprises, helpful information and relevant input throughout the research.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data accessibility

The data described in this article and raw data are available from the authors upon request.

Ethical approval

As no personal or sensitive data—information related to religious, philosophical, political or trade union opinions or activities, ethnic origins, intimate personal details (such as mental, physical or psychological state), social welfare measures, or criminal and administrative sanctions—were collected, an ethical review was not requested (it is not an institutional requirement at the University of Geneva). Nevertheless, informed consent was obtained from all participants. The questionnaire clearly stated that it was anonymous and that all responses would be treated in an aggregated manner. During the interviews, participants were asked for their consent to be recorded and informed that the recordings would be used as data for a scientific publication. They were also notified that any quotations would be presented anonymously, with only their job title being referenced. All participants agreed to these terms.

Funding

This research was carried out as part of the SwissM4EEE project in the context of the partnership between the Chair for Energy Efficiency at the University of Geneva and Services Industriels de Genève (SIG) and with a grant from the Geneva Energy Agency (GEA). The university’s role in the project SwissM4EEE is to support utilities and public administration in their efforts to set up and run energy efficiency programmes.