1. Introduction

A chronic misallocation of the UK’s abundant housing stock (Tunstall 2015) means three-quarters of UK households have either just enough or not enough living space (Gough et al. 2024). This creates wellbeing problems in cramped households (Samuel 2023), whilst excess space due to under-occupation has consequences for energy sufficiency and therefore the climate (Drewniok et al. 2023; Huebner & Shipworth 2017). Such disequilibrium between those with too much space and those without enough could be resolved in a perfect market—one where house moves are cheap and easy to make, and movers have complete choices with incentives to downsize (Meen & Whitehead 2020). In the UK, however, a combination of transaction taxes, borrowing constraints and too few homes for sale mean mortgaged households can struggle to trade up when their needs change (Hudson & Green 2017). Meanwhile, dual-career households can become especially trapped in higher value areas where dwelling sizes are smaller (Costa & Kahn 2000). These are growing problems in the 21st century because longer, healthier lives, more precarious careers and non-linear life courses, mean changes in housing needs now happen more frequently (Gratton & Scott 2020).

Academic fixes for such problems have struggled to address the underlying mismatch and sufficiency issues. Rather, they tend to focus on popular but peripheral factors such as vacant or second homes (e.g. Gough et al. 2024), or else recommend relatively exceptional living arrangements that rely too heavily on space sharing and specific social preferences to be suitable for the mass market (Chiodelli 2015; Delgado 2012; Graham 2023a; Sargisson 2012). Meanwhile, consistent with the literature on adaptability in housing (e.g. Kendall 2022; Saarimaa & Pelsmakers 2020; Schneider & Till 2007), a recent special issue of Buildings & Cities journal did not branch into economic and real estate aspects (Pelsmakers & Warwick 2022). Instead, this paper is premised on a conceptual housing system—hereafter described as ‘adjustable housing’ (Figure 1)—that seeks to design multi-apartment housing so that price-constrained households may continuously expand or contract their homes over time through a combination of spatial and tenurial mechanisms (Graham 2023b).

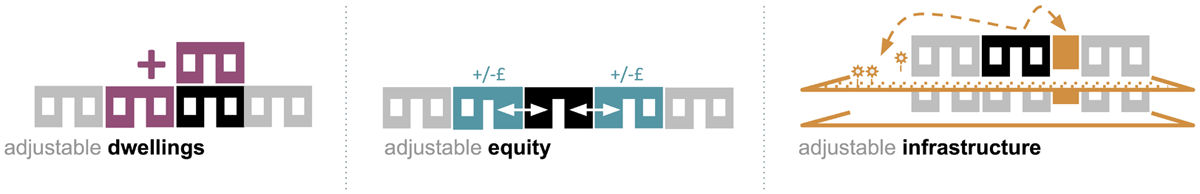

Figure 1

Adjustable housing combines (from left to right): joinable/divisible dwellings that can be connected vertically as well as horizontally; alternating tenures to encourage downsizing; and shared infrastructure for spill over (e.g. shared outdoor spaces and amenities such as storage and guest rooms).

The aim of this paper is, however, not only to advance and communicate adjustable housing as a theoretical basis for the improvement of spatial and energy sufficiency in new residential developments. Rather, it is to recast the theory as a conceptual framework, and in a format suitable for onward testing and validation. Validation is needed to test the possible spatial and energy sufficiency outcomes when residents are free to continuously adjust their consumption of housing space over time. A functional unit along these lines would evaluate performance in terms of the intended outcomes and end-use application (US DOE, n.d.: 3). Instead, however, the industry continues to use units that are blind to occupancy and therefore sufficiency (Francart et al. 2020). For example, building performance is measured in terms of the energy used per m2 of floor area over time (kWh/m2/year), with the effect that without referral to complementary metrics, a well-performing palace for one person would score well. Yet, this functional unit remains the industry standard, with green mortgagors relying on it for discounting loans on well-performing homes—in turn, affecting what is built (Jane & Sayce 2020: 388). Another problematic functional unit is dwellings per hectare, from which housing densities become fixed at the planning stage (Kearns 2022; RICS 2021). An alternative would be for approvals to be based on habitable rooms or bed spaces, so that housing densities—the actual number of apartments—could vary over time (Graham 2023a).

The adjustable housing model would appear to offer a basis from which to establish a functional unit for describing a sufficient level of housing consumption per person. This aim is complicated, however, by the problem that per person outcomes will depend on the interdependent behaviour of multiple coexisting households, working competitively but potentially also collaboratively over the longer term. It is this complexity that leads to the recommendation of a design game or playable metagame as a suitable method for validating adjustable housing. Metagames are an approach to playing a game rather than the game itself. By recasting a conceptual framework as a participatory, multi-stakeholder game environment, metagames can reveal statistical and qualitative insights from players’ strategic, mediating behaviour, as would be harder to obtain through formal analysis of the underlying model (Bots & Hermans 2003).

The paper is structured as follows. The background to the UK’s housing problems is presented in terms of housing space sufficiency, the adjustable housing concept is then explored. Next, design games and their applications are introduced. This leads to a recasting of the adjustable housing system as a conceptual framework, upon which a beta version of the game could be based. The discussion considers the suitability of elements from a tentative beta version of the game, for certain industry applications. The paper concludes with the launch of the concept as a theoretical basis for development and validation by the gaming community.

2. Background

The built environment is the UK’s second highest greenhouse gas emitter by sector, producing around 23% of combined direct and indirect emissions (CCC 2020, 2023). Furthermore, 40–70% of a building’s whole-life carbon footprint comes from the fabric alone (George et al. 2020; Mitchell 2022). Whilst more political ambition and life-cycle management could mitigate emissions embodied in the building fabric, the scale is such that if the UK keeps to its current levels of construction, it will not only have used up its 2050 carbon budget for house building by 2036 but also have produced an excess of floor area per capita in the process (Drewniok et al. 2023). Given this background, it would appear that an increase in the supply and size of new housing would be a positive outcome, because the UK average of 37.5 m2 per person is below the European average of 40.5 m2 (Drewniok et al. 2023). Bigger homes, however, also mean higher whole-life carbon throughputs (Longhi 2015; UKGBC 2021). Furthermore, the increasingly unequal distribution of housing space in the UK means that averages are irrelevant to wellbeing, because some households have more space than they need and others do not have enough (Tunstall 2015). This implies that the definition of ‘energy sufficiency’ is not being achieved, because this would require that all households’ ‘basic needs for energy services are met equitably’ (Darby & Fawcett 2018: 8).

Despite the apparent persistence of these problems, recommendations in the architectural and economic literature appear, initially, to support ways of improving spatial and energy sufficiency. The first is to make certain tax reforms which—though well understood and widely supported by economists—remain persistently illusive for political and path dependency reasons (Hilber & Lyytikäinen 2017; Meen & Whitehead 2020). These may therefore be disregarded. A second recommendation is that more downsizing activity should be encouraged, so that underused housing space might be more equitably distributed to those who need it. Yet, despite the potential to make ‘huge’ savings in whole-life carbon by reducing the need to construct new homes, downsizing activity tends to be restricted by structural, social and market factors (Huebner & Shipworth 2017), as well as by people’s reliance on established networks, especially in older age (Burgess & Quinio 2021). A third recommendation is for a sea change in housing culture in favour of minimum viable living spaces. Various means of defining ‘minimal’ have been explored, whether based on ‘eco-efficiency’ (Cohen 2021), ergonomics (Nourian et al. 2021), user preferences (Lo et al. 2015), mass customisation (Marchesi & Dominik 2017), home working (Holliss 2021: 374–375) or a greater reliance on shared amenities (Lorek & Spangenberg 2019). Yet, people in such minimal homes will tend to face wellbeing issues when their needs change, or else move, creating transience and a loss of community for those left behind (Graham 2023a). This one-way process of spatial accumulation is illustrated in Figures 2 and 3, with Figure 4 showing how this excess might aggregate if excess space were to be measured over a lifetime.

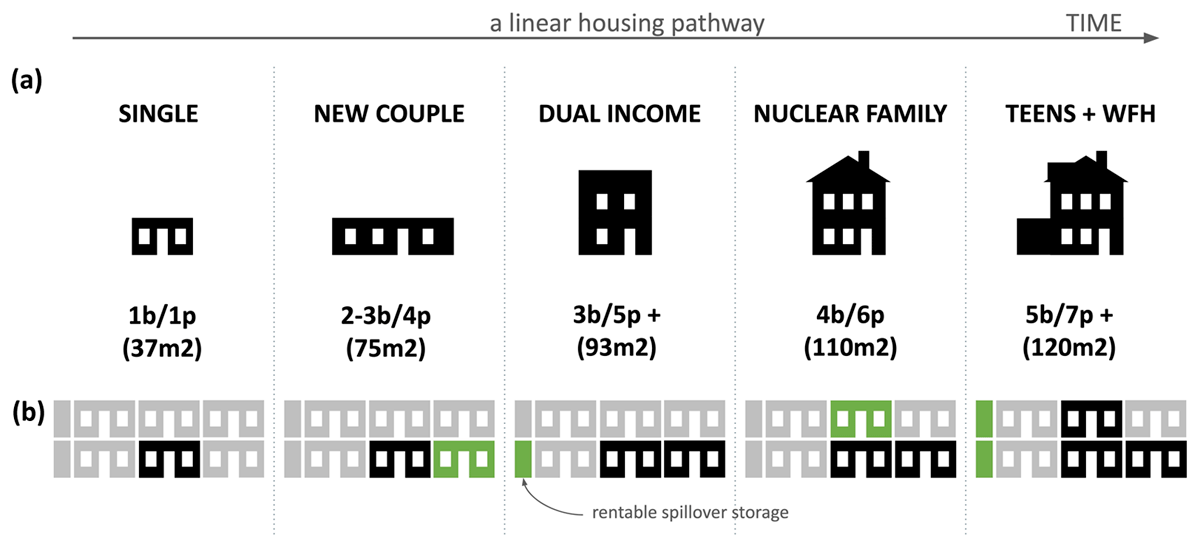

Figure 2

(a) A possible housing pathway where the upward house moves and home extensions are the normal response to life-stage events and employment changes such as working from home; and (b) the same events accommodated by connecting units of adjustable housing modules.

Note: Dwelling sizes reflect UK space standards, where 1b/2p = one-bedroom apartment for two people, etc.

Source: DLUHC (2015).

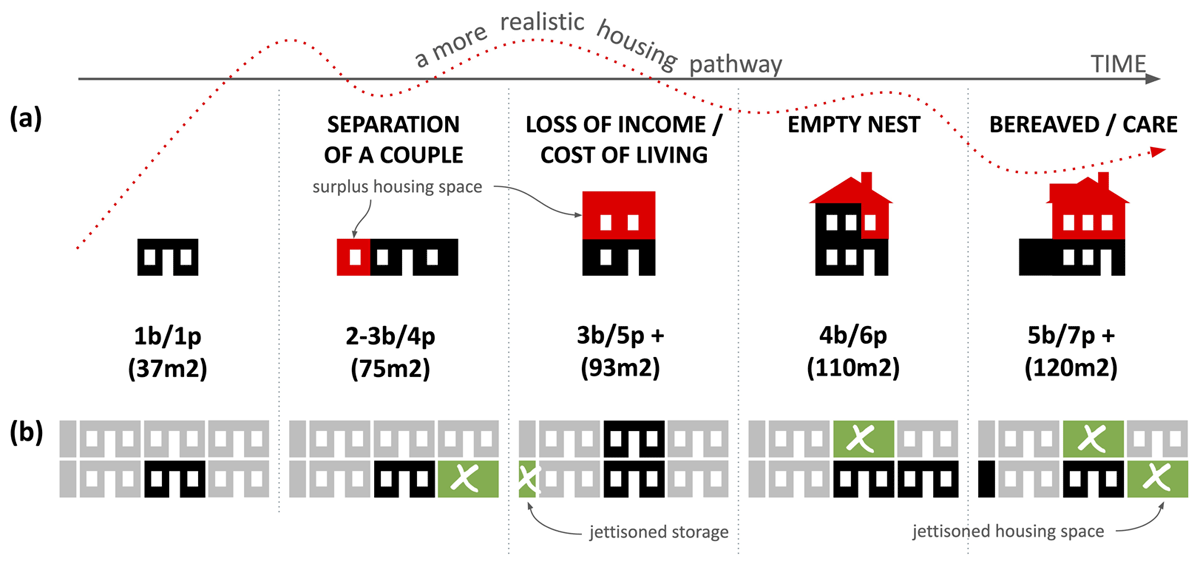

Figure 3

(a) What may seem like sufficient space can become excess, unwanted or under-used space (red), given certain life-cycle events; and (b) in contrast, a continuously adjustable alternative is shown where the potential to rightsize is achieved by discarding surplus space (green).

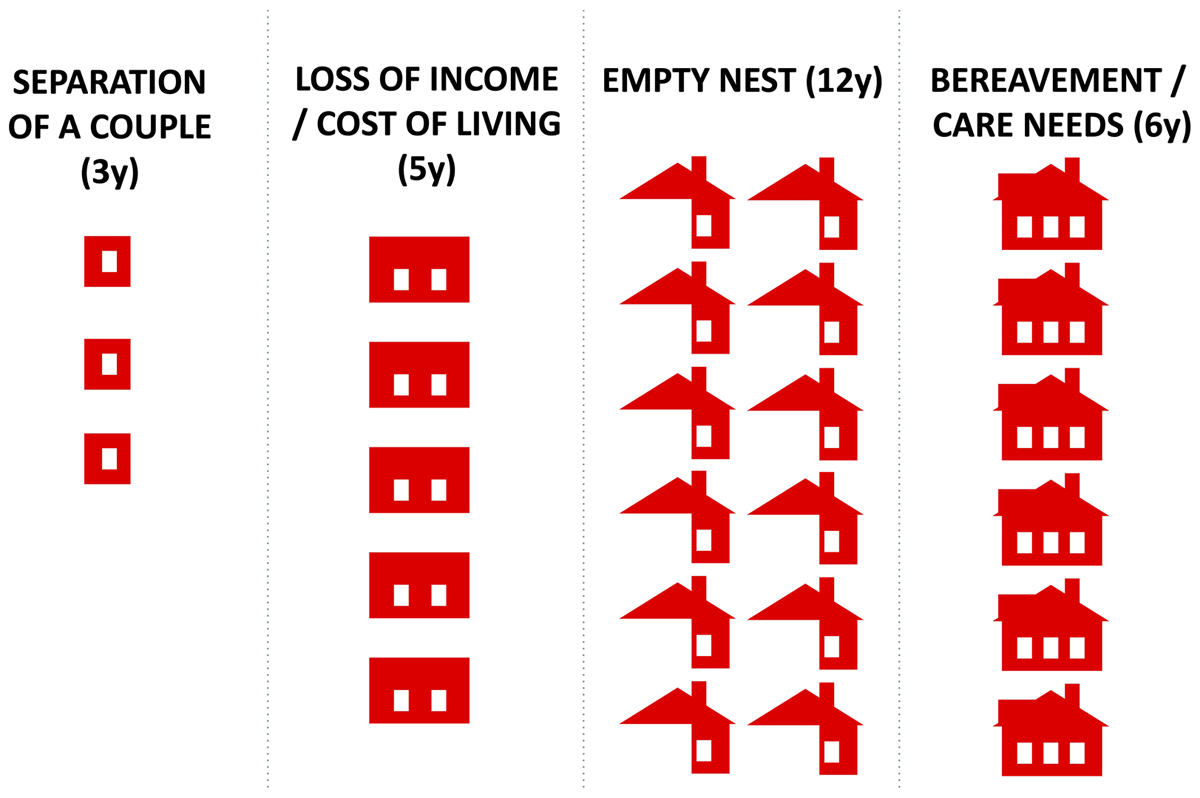

Figure 4

The excess housing space illustrated in Figure 3 can be expected to have significant energy costs when aggregated over time. It is assumed here that the period of under-occupancy following a couple’s separation might last for three years, a loss of income for five years, an ‘empty nest’ for 12 years and bereavement for six years.

Notwithstanding the problems of compact housing, it is nevertheless worth dwelling on definitions of ‘minimal’ and ‘excess’ space, on the basis that the externalities associated with micro-housing should matter less in an adjustable housing scheme—one where the dwelling sizes are no longer fixed, and the system includes incentives to downsize. One definition comes from the bedroom standard, as enshrined in the Housing (Overcrowding) Bill 2003 (UK Government 2003). This is more prevalent in policy-facing research and compares the number of available bedrooms with the number required. For example, the bedroom standard was used in the 2021 Census to reach the conclusion that 69% of UK homes are under-occupied (Bruce et al. 2023). In contrast, architects, planners and developers are more likely to use the UK’s space standards minimums (DLUHC 2015).

It is from these space standards that Gough et al. (2024) derive a useful measure of sufficiency as being 40 m2 of living space for the first person, then an additional 10 m2 for each subsequent household member. This provides a useful basis from which to understand sufficiency in housing as being more than distinct ‘units’ or apartments that are fixed by the architecture, or by artificial constructs such as ownership and planning (Blandy 2014), but rather as modules of living space that could be allocated according to housing needs that can and will change.

3. What is adjustable housing?

The conceptual premise of adjustable housing is that it creates an architecture in which an affordably small ‘starter’ apartment may be joined or divided from adjacent modules of living space over time, until the floor area matches any changes in that household’s housing need. The spatial element of the system is akin to that found at a scheme on Hellmutstrasse, Zurich, Switzerland (A.D.P. Walter Ramseier, completed 1991) where multiple party wall arrangements are available and can be varied over time (Till & Schneider 2005) leading to at least 13 recorded alteration events to date (Walter Ramseier, personal communication, 26 July 2024). This connectability may be combined with spillover access to shared outdoor spaces and certain rentable amenities, reminiscent of a limited version of cohousing (UK Cohousing Network 2021), although the benefits of indoor shared spaces in terms of spatial and energy sufficiency remain inconclusive (Francart et al. 2020).

The conceptual innovation of adjustable housing comes from two adaptations to this Hellmutstrasse model. The first is the ability to connect modules vertically—not just horizontally—thereby creating more configuration options and more frequent opportunities to expand. A second comes from its adaptation to the UK context, where homeownership is not only politically entrenched (Jackson 2012) and culturally normal (Foye et al. 2018), but also the dominant tenure (DLUHC 2023). For this reason, it is important that the occupier has the option to buy their main or ‘starter’ apartment, even if, thereafter, they may only rent any additional modules to which they connect (Graham 2023b). This is so that monthly rental costs—combined with the costs of heating and maintenance—create an extra incentive to downsize by relinquishing space rather than facing the cost and upheaval of moving house. In this way, the hypothesis is that being a part-spatial, part-tenurial system, the adjustable housing concept should enable and encourage ‘rightsizing’ behaviour, thereby improving spatial and energy sufficiency outcomes in aggregate.

4. What is a design game?

The recommendation of this paper is to frame the adjustable housing situation as a reflection on the decision issues that stakeholders will face over a complete life-cycle. In this regard, design games are useful research methods for replicating the complex performance objectives and non-linear decision variables that drive design choices and consumer preferences in real-life, multi-actor, multi-criteria environments (Azadi & Nourian 2021a, 2021b; Nourian et al. 2021, 2024). They can also generate data to inform the development of derivative evidence-based design tools, such as multi-agent, simulation-based design processes. In addition, the game itself can be used as a simulation mechanism to study the effects of the interplay of human agents with a conscious agency, instead of working with computerised agents. Most notably, design games have been used to facilitate community participation (Gillick 2023; Sanoff 2016), address issues of conflict and cooperation in the planning process (Building 2008; Waite 2008), raise or explain political issues (Kipnis 2018), test policy systems (Perla & McGrady 2011), unlock multi-stakeholder infrastructure projects (Bots & Hermans 2003), and find ways of maximising the wellbeing of older residents in new housing, using limited resources (SCIE 2024).

Given such precedents, serious or purposeful games seem highly suitable as a method for testing the sufficiency outcomes available from an adjustable housing scheme. Specifically a metagame approach is suitable because it frames the problem so that players’ choices can be analysed to reveal the options available and with whom the power lies (Bots & Hermans 2003). Metagames are related to design games, simulation games and agent-based modelling, i.e. as serious or purposeful games that are not just for fun. These are most successful when they can be decomposed into the three elements or ‘worlds’ of (1) reality (i.e. a recognisable problem), (2) meaning (i.e. a value proposal) and (3) play (i.e. a goal) (Harteveld 2011). Success on these terms requires the translation of theory into metagame by means of a conceptual framework in which the component parts are made clear.

The first of these ‘worlds’ is meaning, which, in an adjustable housing scheme, comes from the emphasis on design value. This has been defined as having three parts: social, environmental and economic (Serin et al. 2018). Another aspect of meaning—the value proposition—comes from the underlying objective of expanding residents’ capabilities in a way that gives them the freedom to meet their changing needs (Foye 2020; Kimhur 2020; Robeyns 2005; Sen 2010). The second element—play—is fulfilled by giving residents the strategic goal of achieving a sufficient amount of space through a process interdependent on the needs and choices of others. This collaborative, playful element is also likely to produce a better understanding of the challenges and design opportunities that exist between diverse stakeholders, and in the process uncover nuanced barriers and enablers that might otherwise have remained elusive (Kleinsmann & Valkenburg 2008; Sanoff 1979). The third of these ‘worlds’—reality—comes from the game’s conceptual engagement with certain elements of the UK’s housing situation. Specifically, these include the problems of affordability, market liquidity and restrictions on choice (Burgess & Quinio 2021; Foye & Shepherd 2023; Hudson & Green 2017; Huebner & Shipworth 2017; Meen & Whitehead 2020; Preece et al. 2020). The element of reality also relates to the attempt to simulate shared ownership and shared equity arrangements (Cromarty 2020; Smith 2015; Whitehead & Williams 2020), but by using the architecture to help occupiers more easily distinguish between rented and owned modules of living space.

5. A conceptual framework for adjustable housing

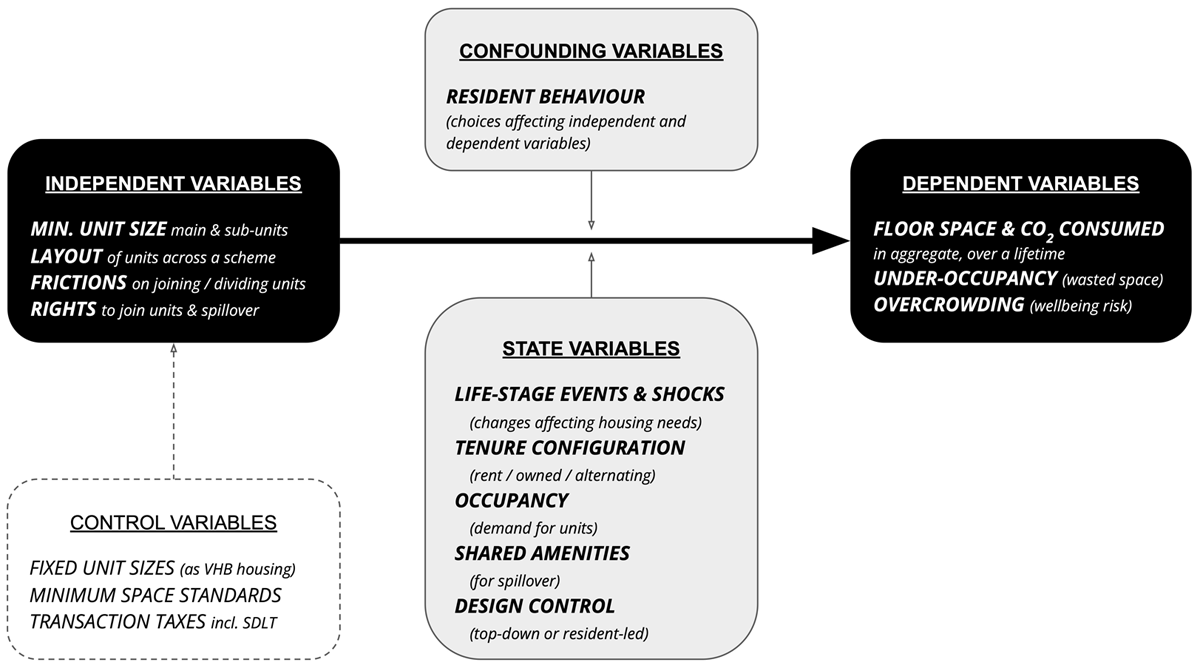

These key functions of an adjustable housing system can be described through a conceptual framework diagram (Figure 5). This helps to explain how different inputs of connectable, mixed-tenure apartments with certain sizes and rights over shared amenities (independent variables) might produce variations in spatial and energy sufficiency outputs (dependent variables). The state variables describe mediating and moderating factors that shape this relationship. These are: life stage events (whose probability changes with the age of the household head); configuration of tenure (e.g. all rented, all owned, mixed or alternating); occupancy (i.e. household size); the availability of shared amenities (e.g. garden, storage, guest rooms, etc.); and the degree of freedom that residents have to change the input (independent variables) to meet their emerging needs. All the choices and interactions available to residents of an adjustable housing scheme may be thought of as confounding variables. This is because only the strategic behaviour of residents will reveal the available options. It should be possible, however, to predict other probability problems using national statistics, such as the likelihood of bereavement or having a child at different age groups (ONS 2021, 2023).

Figure 5

Conceptual framework of the adjustable housing proposition.

Note: SDLT = UK’s Stamp Duty Land Tax, payable on property transactions; VHB = volume house builder.

The inclusion of control variables indicates the need for any validatory process to compare an adjustable arrangement against a standardised and inflexible volume housebuilder model. These models are typically designed to maximise short-term profitability rather than longer term social or environmental value (Samuel 2023: 38–39) and normally offer only fixed dwelling sizes of a single tenure with no shared amenities. Comparison is needed so that differences in the frequency of house moves, or the aggregate consumption of housing space, can be observed, as these may expose relationships that occur at a local level (i.e. a single estate or housing development), but which are typically buried in data on housing needs or affordability that reveal only the macro-picture.

A closer examination of the state variables helps to explain why adjustability affects spatial sufficiency. For example, tenure configuration is important because any modules of living space to which a homeowner connects and thereafter rents will create a monthly liability and therefore an incentive to rightsize. Meanwhile, rights over shared amenities are important because access to these will enable spillover into semi-private space, thereby relieving some pressure from the private dwelling. The element of design control is also important because an arrangement in which tenure and/or the fixity of dwelling sizes are laid out in an alternating pattern across a scheme is likely to produce a different output from one arranged more organically or by the residents themselves. For example, an entirely mixed, tenure-blind arrangement (also known as pepper-potting in industry) is likely to produce different outcomes from more top-down management of apartment buildings, in which the separation of tenure is typically stair core by stair core. For these reasons, it is likely that certain non-spatial aspects of multi-dwelling living will affect spatial and energy sufficiency.

6. Discussion: a beta version of ‘rightsize’

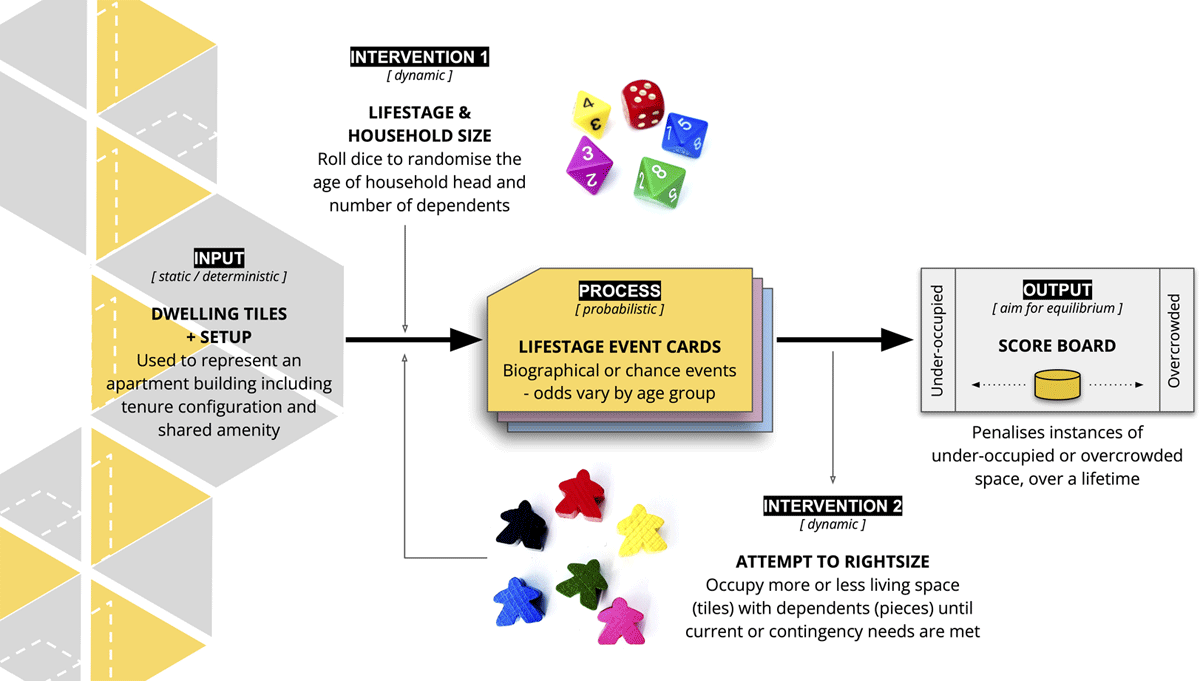

The process of tentatively designing a beta version of a metagame has helped to understand how the theoretical basis and conceptual framework of adjustable housing might be converted into a participatory research method. This exploration into the world of game design was, however, taken only so far as to understand the broad mechanics of a gamification method (Figure 6). Further encoding and game design expertise will be needed if the concept is to be made accessible to experts and diverse stakeholders. Thus, a more detailed summary of possible game rules, strategic options and suggested format is shared as a markdown file on the developer platform GitHub. This means that the discussion hereafter is written in prose rather than game notation, as a theoretical basis or primer for the gaming community. Its purpose is to explain how—with onward development—the key principles of adjustable housing might be used to reveal certain strategic behaviours and data for analysis.

Figure 6

Overview of the design game that builds on the conceptual framework shown in Figure 5.

Described hereafter as a game called ‘Rightsize’, it is recommended that any metagame arising from this paper should cast ‘players’ as if they were residents in a multi-dwelling, adjustable housing environment. In this way, they will assemble households in apartments whose size should reflect the housing need. Such an environment could be created using tiles to depict connectable modules of living space. Readers with experience of the tile-based game Carcassonne, or Settlers of Catan, will recognise the concept of using tiles to represent real estate that may be occupied—potentially for scoring purposes. In experimenting with a beta version of the game, square or hexagonal tiles emerged as useful shapes with which to represent dividing walls and occupiable segments of floor space. Placed edge to edge, the square format can be used to assemble a two-dimensional floor plan, whilst hexagonal tiles begin to represent a cut-away axonometric projection of a somewhat abstract apartment building. Tiles are also suitable for tabletop gaming (Figure 7)—a setting known to improve strategic learning and information sharing between players (Bots & Hermans 2003).

Figure 7

Playing a beta version of ‘Rightsize’ using printed dwelling tiles and pieces gathered from other games.

To understand how this recommended game environment could be animated by player activity, it is helpful to return to Harteveld’s (2011) three ‘worlds’ of meaning, reality and play. Turning first to meaning, any game should allow individual and collective objectives to exist concurrently. This is to ensure a continuous balancing act between aspects of social, environmental and economic value—the three types of design value (Serin et al. 2018). Hence, the individual aim of these players should be to accommodate changing or anticipated housing needs through multiple rounds. Simultaneously, their collective aim should be to maintain sufficient living space for their own household’s needs but without causing overcrowding for others. This means achieving sufficiency in the aggregate through a mediating process that rewards efforts to minimise any waste of space and therefore energy and building materials. Such sufficiency-oriented behaviour should be reinforced through penalties or rewards in the scoring system, so that players are encouraged to find a balance between overcrowding (to minimise wellbeing losses) and under-occupation (to minimise energy costs). In this regard, analogies may be made to Nash’s game theory of equilibrium in which all players arrive at a point where they would not change their last move (Becchetti et al. 2020).

Turning next to play, the game should reflect the part-spatial and part-tenurial aspects of the adjustable housing model. This could be achieved by giving each player the option to ‘buy’ the first module of living space they occupy when starting an apartment and would reflect cultural UK’s preferences towards ownership. Thereafter, as players attempt to accommodate the remaining dependents, they would be notionally renting the subsequent modules of living space they occupied. This would encourage them to rightsize their home over time by adding or removing rented modules, but without relinquishing the module they own. In spatial terms, the gameplay might also connect a scoring system to existing measures of excess space. A suitable basis for this would be that used by Gough et al. (2024), where sufficient living space was defined as having 40 m2 for the basic dwelling (notionally the main living spaces, bathroom, circulation and a single bedroom) then an allowance of 10 m2 for each additional occupant (notionally for bedrooms). Such a simplification of UK space standards should consider some allowance for stairs, as would normally occupy the equivalent of a further bedroom space (DLUHC 2015). In both game and concept, stairs allow apartments to expand vertically as well as horizontally, thereby increasing optionality.

Turning next to aspects of reality, it is crucial that Rightsize simulates the idea that a household’s needs are rarely static. To make this explicit, three variables—perhaps randomised—should exist. First, the number of dependents in each household should vary between players and thereafter over time. Second, the age group of each head of household should be different at the outset and thereafter increase—perhaps by a decade at each turn. Third, certain life course events should come to bear on housing needs—perhaps using chance cards. This would be for the purposes of simulating changes in household composition, of the sort that research has found can affect the consumption of housing space or trigger a house move (Clark & Lisowski 2017; Ong ViforJ et al. 2021; Wood et al. 2017). Relevant changes might include ‘biographic events’ (e.g. cohabitation, pregnancy, adoption, bereavement, children leaving or returning to the family home); care events (e.g. parenting, pets, the need for a carer or nanny, and visitors such as stay-over or live-in relatives); employment events (e.g. home-based working, job loss or retraining); storage needs (e.g. bikes, sports equipment, projects or furniture); amenity needs (e.g. garden, exercise room, making space or vegetable growing); and financial shocks (e.g. lockdowns, energy spikes or interest rate shocks). The probability of these life stage events would typically vary depending on age groups (i.e. older age groups would have higher odds of bereavement but lower odds of pregnancy).

Several variations may help to extend the range of data available from the basic game described above. A commercial variation could be integrated to represent a notional building owner, e.g. a private freeholder, a build-to-rent investor, a housing association, a local authority or a resident-owned cooperative. These entities might notionally own any unoccupied living spaces in return for rental income, or to allocate subsidies or give more control to residents. Such stakeholders have financial interests in assessing the investment viability of an adjustable housing scheme in terms of the resulting rental income, space allocation (especially for publicly owned housing) and void risks (i.e. unrented modules of living space generating no revenue for an investor) (Graham 2023a).

Variations on space occupancy rules may also be available. For example, up to two dependents could be allowed in each additional module of living space, such that dependent children or cohabiting adults could share a room. This would tilt the game towards the UK’s bedroom standard (UK Government 1986) rather than space standards (DLUHC 2015), and could provide insight into the effects on space sufficiency in the event of marital breakdown or children of different genders becoming teenagers. Another alternative could be to permit house moves or swaps within the scheme. Another could be to test the occupancy benefits of shared amenities or spillover spaces in the game environment. Examples might include a bike shed, project space, guest apartment, storage, gardens, laundry or vegetable growing—as featured in many cohousing schemes (Francart et al. 2020; Graham 2023a; UK Cohousing Network 2021).

Lastly, there are options for variations to the basic game to simulate different management scenarios. Of these, one could be to allow different tenure arrangements such as 100% rented, 100% owned or a bottom-up, user-led configuration where players are free to choose. A variation on this could be used to simulate mass-market housing, complete with fixed dwelling sizes of a single tenure and no shared amenities. This would allow observers to gauge differences between adjustable housing and a mass market benchmark or control variable, as described in the conceptual framework diagram.

7. Conclusions

The problem of unequal space distribution in UK housing cannot be resolved simply by building new homes. One reason for this is that both housing policy and the housebuilding industry lack a functional unit for expressing the consumption of energy and space, in terms of what is sufficient (or enough) per person. Theoretically, a suitable functional unit could be estimated based on the sufficiency-oriented housing solutions described in this paper. This is because sufficiency outcomes in multi-apartment housing rely heavily on the adjustability of space and tenure. Such an arrangement could enable and even encourage rightsizing activity over time. Validation, however, will require new methods to simulate the complex and interdependent socio-spatial relationships through which sufficiency outcomes might arise.

A metagame—or, a context-adaptable blueprint of the design game—appears a suitable validation method as it may be extracted for UK or other situations. This approach can create tabletop or digital environments in which stakeholders’ strategic behaviour could be observed to produce data for the quantitative and qualitative analysis of interplays between architecture, tenure and sufficiency. Such serious or purposeful games require a combination of reality, meaning and play. The element of reality is grounded by co-authorship that combines expertise and perspectives from housing design practice, architectural gamification, spatial cognition, and direct experience of real-world housing delivery in a UK housing association. The paper also brings an element of meaning to the problem by devising a conceptual framework to explain sufficiency as a value proposition. Last, to advance the element of play, this paper has laid out the theoretical basis for a metagame based on a tentative beta version for future development by the gaming community.

Put together, this grounding in housing delivery underpins both the conceptual framework and the gap to be filled. It also adds weight to other applications of architectural or planning games, helping to demonstrate the acceptability of a serious game approach amongst professional, supply-side audiences, for decision-making and training purposes. Beneficiaries should include designers, developers, planners, investors, lenders and educators. The game also offers learning outcomes for occupants of all tenures, emphasising the importance of interactions—or play—in gathering diverse stakeholders with differing viewpoints and values. This is to produce a collective understanding of the necessary trade-offs for delivering sufficiency in a housing context. To advance this understanding, what is needed next is a common definition of sufficiency needs, and a game approach is the way to develop such learning. Ultimately this will require a new, practically usable, and appropriate functional unit for measuring and benchmarking housing sufficiency.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Behaviour and Building Performance research group at the University of Cambridge, who convened a session to hear and advise on the paper’s proposition. Acknowledgement is also due to Jonathan Hey—creator of sketchplanations.com and author of Big Ideas Little Pictures (Media Lab Books, 2024)—for advice on graphics and the user experience during the development of the beta game. Thanks also to Robin Nicholson (Cullinan Studio) and Chris Twinn (Twinn Sustainability Innovation) for help with the surprisingly difficult question of estimating the built environment’s greenhouse gas emissions as a share of the UK total. Lastly, thanks to Rhiannon Maddocks for proofreading.

Author contributions

PG: conceptualisation, methodology, visualisation, writing lead, original draft preparation, review and editing, game testing and insight from housing design in architectural practice. PN: conceptualisation and advice on gamified methods for participatory housing development. Review and editing of writing. EW: reviewing and editing of writing. Input on housing delivery. MG-M: Original advice on design game method and introductions. Review of first submission.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Data availability

A more detailed summary of possible game rules, strategic options and suggested format is deposited on the developer platform GitHub: https://github.com/PLGraham/Rightsize. This exists as a markdown-formatted text file so that members of the gaming community can develop the conceptual framework into a workable game, with reference to the theoretical basis laid out in this paper.

Ethical consent

Ethical approval was not required for this methods paper, as neither personal data nor human participation was required, beyond that of the authors.

Funding

The lead researcher was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC)—part of UK Research & Innovation (UKRI)—as an Innovation Scholar in Architecture and Design (grant reference number AH/X005097/1). This has enabled a three-year secondment from Cullinan Studio Ltd (architects) to the University of Cambridge’s Department of Architecture. Publication costs for this article have been met by the University of Cambridge.