1. Introduction

Housing companies (i.e. large-scale public and private organisations that own and/or manage residential rental properties) help to create, maintain and develop the built environment through their housing provision. Besides their core activity of providing housing, they increasingly also find ways to help mitigate societal problems and contribute to social, environmental and financial sustainability. The reason for this is because housing plays a particularly important role in sustainable development due to its large square footage within the built environment and its ability to promote sustainable lifestyles, wellbeing and quality of life (Nielsen et al. 2009; Heitel et al. 2015; Morgan et al. 2022).

One example of an intervention performed by housing companies, which lies outside the formal responsibility and core competency of providing housing (Troje 2023), is to create meaningful activities for tenants that benefit their employability, skills, careers, and physical and mental wellbeing. These ‘activity interventions’ are used as used as a vehicle by housing companies to create social value, and entails creating jobs, offering skills training or leisure activities for tenants. Many Swedish housing companies are increasingly conducting different activity interventions for their tenants, but this requires investment in new practices, knowledge and technologies, meaning that much of the work is currently ad hoc (Troje 2023). The same situation is found in other countries, such as the UK (Fujiwara 2013; Raiden et al. 2019). Fujiwara (2013) states that such interventions surely have an impact on communities and wider society, but it is unclear what sort of impact they have, and how they affect housing companies’ bottom lines.

The aim of this paper is to investigate: (1) housing companies’ initiatives to provide meaningful activities for tenants; (2) what value these interventions create; and (3) how social value creation relates to financial value. Meaningful activity in this context means activities that raise social value for those targeted by the interventions, e.g. career opportunities, employability, practical and personal skills development, and physical and mental wellbeing.

The focus is on the facilities management (FM)/operations phase of a building’s life cycle, i.e. the phase concerned with maintaining, developing, extending and refurbishing the building stock. By focusing on this under-researched phase, the paper adds a novel insight into how the built environment can use its entire life span to contribute to social sustainability.

2. Frame of reference

2.1 Housing companies in a Swedish context

A Swedish housing company can be a private or public organisation that owns and/or manages residential properties for rent. According to the Swedish national employer organisation for regions and municipalities, Sveriges Kommuner och Regioner (SKR), the main responsibility of public housing companies is to foster housing provision in the municipality. Within this responsibility lies the task of accommodating different housing needs, which means that housing companies must provide a varied housing supply of good quality that can attract different types of tenants (SKR 2020, 2023).

Public housing companies are by law required to act in the public’s best interest, and are also required to be run in a commercial manner (i.e. for profitability and organisational longevity). The reason for this is not to skew the competition in the housing market. Public housing companies should therefore not act in ways that are commercially unmotivated, as they have market-based requirements for financial returns. In practice, this means that private and public housing companies in Sweden are managed in a very similar manner (Grander 2017; SKR 2020, 2023).

Although public housing companies are required to contribute to their municipality’s sustainable development, and can have different individual policies for social value, they are by not explicitly required to create employment, leisure activities, education or training for tenants or other citizens. This means that offering different types of activity interventions for tenants lies outside of the formal responsibility of both public and private Swedish housing companies (Troje 2023). The Swedish for-rent housing market has become increasingly deregulated, which has led to public housing companies becoming market based and profit-driven. This means that rent is increased to generate more profit, which results in low-income tenants being less desirable—even for public housing companies (Grander 2017; Maine et al. 2022). This has also led to an increased segregation between wealthier and poorer neighbourhoods. The supply of (affordable) rental housing has decreased, and the Swedish housing market is becoming increasingly similar to what is seen in the rest of the European Union (Grundström & Molina 2016). In effect, the concept of social sustainability is sometimes used to hide and legitimise covert profit-making agendas that may actually be unsustainable (Stender & Walter 2019).

Swedish housing companies can be considered as ‘hybrid’ organisations. They strive for financial prosperity and are profit-driven by market ideals and competitiveness, but are also mandated to fulfil social responsibilities and supply housing to all demographics (Grander 2017). Maine et al. (2022) investigated how striving for both financial prosperity and social sustainability affects the performance of Swedish public housing companies. They found a positive relationship between financial and social performance. As such, both in Sweden and internationally, housing companies can profitably use their operations as a vehicle to fulfil socio-economic goals at a local level (Alexander & Brown 2006; Fujiwara 2013).

2.2 Social value in housing

What social value means within a housing context is not precisely defined and may be intangible. Most scholars agree that it encompasses aspects such as social integration, inclusion, and participation, collective and individual wellbeing, health, safety and happiness, and accessibility to housing, education and employment (Dixon 2019; Raiden et al. 2019; Stender & Walter 2019; Morgan et al. 2022). The UK Green Building Council (UKGBC) defines social value as:

created when buildings, places and infrastructure support environmental, economic and social wellbeing, and in doing so improve the quality of life of people.

Many of the aspects that compose social value are interrelated. For example, housing can be a source of wellbeing and hope both for individuals and entire communities. In this context, wellbeing relates both to social, environmental and financial wellbeing, and encompasses features as empowerment and sense of purpose. Being employed, getting an education and having active spare time has a direct positive effect on wellbeing (Fujiwara 2013; Trotter et al. 2015; Samuel 2022). Due to the breadth of aspects encompassed by social value and the interconnectedness of these aspects, the range of activities housing companies engage in goes beyond providing somewhere to live. For example, housing companies must now also address issues related to climate change, energy and resource-efficient renovation, elderly care, tenant participation, community development, social unrest, and criminality (Heitel et al. 2015). Neighbourhoods where social value is low (e.g. due to criminality or unemployment) are often associated with negative identities of the neighbourhood and of those who live there (Robertson et al. 2010; Gustavsson & Elander 2016). Therefore, these issues have negative effects not only for people but also for property owners as well as for the built environment itself.

2.3 Activity interventions to increase social value

Amongst the interventions that housing companies implement for their tenants, employment creation is a key tool for building socially sustainable and prosperous neighbourhoods for Swedish housing companies (Grander 2017). Elander & Gustavsson’s (2019) study of Swedish urban regeneration and development programmes shows that employment of tenants and their enrolment in courses are the most preferred ways of creating social inclusion in a neighbourhood. Such job creation also serves as a form of citizen participation. Another way of creating employment in the context of housing is to use social procurement. Social procurement is used in many countries such as Sweden, the UK and Australia, where employment clauses are included in procurement contracts. These clauses are used to create jobs, apprenticeships or internships for the long-term unemployed and disadvantaged, such as immigrants, ex-offenders, youths, people with disabilities or Indigenous populations (Raiden et al. 2019; Loosemore et al. 2021, Troje & Gluch 2020).

Troje & Gluch (2020) examined social procurement by Swedish housing companies in their FM operations. Unemployed tenants were hired by housing companies to work with simple maintenance tasks such as minor repairs or managing green areas. Their study reveals that the housing companies felt social procurement provided value for the employed tenants, whose wellbeing increased in terms of happiness, being a role model for their family and community, and feeling good when supporting themselves rather than relying on welfare. The housing companies also saw benefits in terms of their maintenance costs decreasing, and increased employee motivation and commitment. However, despite these positive aspects, those directly supervising the tenants often had to take significant time away from their other responsibilities due to the tenants’ limited education, work experience and language proficiency. Supervisors often had to engage in work tasks outside of their formal work description. This included helping the interns with personal matters (e.g. answering calls from social services or teaching them Swedish). Despite providing a sense of pride for the supervisors, it also added to their work stress.

Research by Loosemore et al. (2021) on a training and employment programme in an Australian FM context reports positive outcomes for participants in the programme, e.g. increased optimism and motivation, and better verbal and written communication. Some of these outcomes also had a spillover effect for their families and community, e.g. reduced substance abuse and crime and increased family cohesion. Those supervising the programme felt they were contributing to good corporate citizenship, and gained increased job satisfaction and leadership skills. The negative outcomes were relatively minor, although costs increased in terms of resources and time for those supervising the participants. Social procurement also requires collaborative partnerships between different types of organisations.

Besides employment and training, creating communal areas such as gardens was found to be important for increasing connectedness within a neighbourhood (Stender & Walter 2019). Communities that are more physically active with closer interactions with neighbours have less criminality and are more prosperous, where communal spaces such as gardens, playgrounds and recreational spaces help promote mental and physical wellbeing and healthy lifestyles (UKGBC 2016).

2.4 Social value creation framework

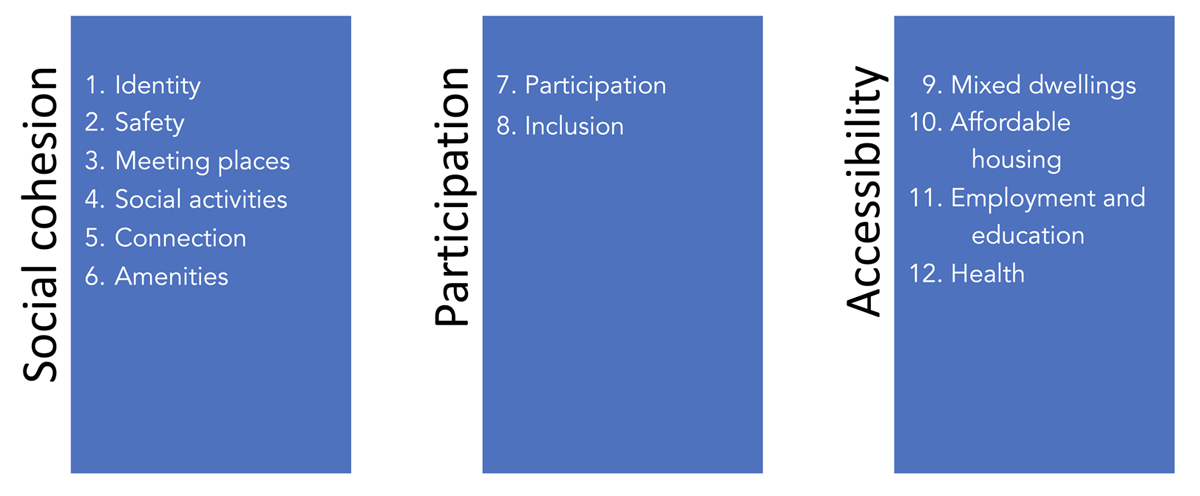

To understand what type of value is created from different activity interventions, the framework of social value creation in a housing context (Stender & Walter 2019) is applied in this paper. Stender & Walter (2019) developed their framework based on a case study of two Danish neighbourhoods, which roots the model in a Scandinavian housing context and makes it appropriate for this paper. The framework (Figure 1) focuses on three main themes of social value creation (social cohesion, participation and accessibility) that encompass 12 different indicators:

Identity: the architectural and neighbourhood identities that give tenants an attachment and sense of belonging to the place in which they live.

Safety: the sense of being safe in the neighbourhood, having spaces designed to reduce criminal activity, and having staff present to deter criminal activity and enable communication with tenants.

Meeting places: places where tenants can socialise, i.e. seating areas, communal gardens, arts and crafts spaces, or venues to host events such as children’s birthday parties.

Social activities: activities that bring tenants together for social, recreational or sports activities.

Connection: the linkage of a neighbourhood to the rest of the city, thus reducing a feeling of separation, e.g. through walking, cycling and transport paths to enable travel to and from the neighbourhood.

Amenities: access to schools, kindergartens, elderly care homes and other service providers within the neighbourhood.

Participation: stakeholder involvement in development processes and creating a sense of ownership over one’s neighbourhood.

Inclusion: neighbourhood design that welcomes all types of tenants and families of different sizes.

Mixed dwellings: sharing amenities with different demographics and socio-economic status, and having different forms of tenure, such as social housing, renting, ownership, apartments and single-family homes.

Affordable housing: efforts to reduce segregation by offering low-income or student housing.

Employment and education: access to good schools, educational opportunities and job opportunities.

Health: neighbourhoods that promote good health, e.g. access to green spaces and social spaces, and non-toxic living spaces free from noise pollution.

Figure 1

Model of social sustainability indicators.

Source: Adapted from Stender & Walter (2019).

The framework offers a way to understand what social value can be created from activity interventions, and the effect it has for the overall social sustainability of a neighbourhood.

3. Method

3.1 Data collection

A qualitative research design was used to capture the social value practices of housing companies and their employees’ perceptions of them (Silverman 2013). The main reason for selecting the specific housing companies included in this study were because these companies have been outspoken about their sustainability work in industry press, marketing materials, on their webpages and at conferences.

The sampled organisations were both private and public and owned and/or managed residential housing (between 4000 and 200,000 apartments) of different kinds (e.g. high-income housing, low-income housing, student housing, old and new building stocks). In this study, low-income housing refers to socio-economically disadvantaged neighbourhoods with lower employment rates, education and graduation rates, increased criminality, and higher portion of immigrant communities. High-income housing refers to middle-class neighbourhoods without much social unrest or criminality. Mixed-income housing refers to a housing company owning properties in neighbourhoods of different socio-economic status, both higher income and lower income neighbourhoods and everything in between. The sampled companies and their housing stocks were geographically dispersed throughout Sweden, and owned housing in the south, central and northern region of Sweden, in both larger and smaller cities. Therefore, the organisation sampling can be seen as heterogenous (Etikan et al. 2016), while still representing typical housing companies in Sweden.

The reason for including companies with a mix of different housing stocks was to get a wider view of sustainable housing management, not just in relation to social sustainability. Also, although there was no initial intention to compare the housing companies, it quickly became evident during the analysis that all the companies (regardless of their public or private status or what type of housing they owned) engaged in similar practices to create social value. As noted by Grundström & Molina (2016) and Grander (2017), public housing companies in Sweden are often managed very similarly to private housing companies. This is the likely reason why no considerable difference between them was observed in this study. The findings show how housing companies conduct these interventions in all their neighbourhoods, albeit certain interventions are performed more or less depending on the needs of each individual neighbourhood. The similarity across the cases supports the wider validity of the results.

For each organisation participating in the study, two to three people were interviewed in order to get both breadth and depth of results. The 23 interviewees worked on a strategic level within their organisations and set the agenda for sustainability and development work (Table 1). The interviewees were thus purposefully sampled (Etikan et al. 2016) based on their influential positions within their organisations and their overview of both operational and strategic value-creation activities.

Table 1

Information on interviewees

| ORGANISATION | COMPANY PROFILE | APARTMENTS | PROFESSIONAL ROLES | INTERVIEWEE CODES |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public housing company A | • Low-income housing | 11,000 | Business development manager, CEO, FM manager | PubA 1–3 |

| Public housing company B | • Mixed-income housing | 26,000 | FM managers | PubB 1–3 |

| Public housing company C | • Mixed-income housing | R&D manager | PubC 1 | |

| Public housing company D | • Mixed-income housing | 20,000 | FM manager, sustainability manager, CEO | PubD 1–3 |

| Public housing company E | • Mixed-income housing | 24,000 | Business development manager, CEO, energy and environment manager | PubE 1–3 |

| Public housing company F | • Mixed-income housing | 23,000 | Development manager, manager of project managers | PubF 1–2 |

| Private housing company A | • High-income housing • Student housing | 4,000 | CEO, FM manager, technical FM specialist | PriA 1–3 |

| Private housing company B | • Mixed-income housing | 200,000 | Development manager, sustainability manager, sustainability specialist | PriB 1–3 |

| Private housing company C | • Mixed-income housing | 39,000 | FM manager, social sustainability manager | PriC 1–2 |

[i] Note: CEO = chief executive officer; FM = facilities management; R&D = research and development.

The interviewees held positions as chief executive officers (CEOs), business managers, sustainability managers, development managers and facilities managers. Sustainability managers were relevant to interview due to their formal responsibility over sustainability issues. Because there is a connection between creating social value and financial value, business managers were interviewed to understand this connection better. CEOs were deemed relevant as they set the overall direction and priorities of the organisation. FM managers were relevant to interview because they work both strategically and operatively to manage and develop their neighbourhoods, which gives them a strong influence of what sustainability interventions are actually implemented in different housing stocks.

The interviews were semi-structured to allow for flexibility in responses (Kvale 2007). The data collection was conducted in the winter and spring of 2021–22 over Teams or Zoom. The interviews lasted approximately one hour, and all but two interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. The topic of the interviews focused on current social challenges the company had to deal with, what interventions they prioritised, what social innovations or interventions showed future promise, what routines and resources they had to work with social sustainability and the activity interventions, how the interventions were organised, and how they collaborated with other actors and organisations in these interventions.

Observational data from three FM industry conferences were also collected. The main theme of these one-day conferences was the future development of FM in Sweden, and they took place during the winter and spring of 2021, 2022 and 2023. The guest speakers came from industry and government, including commercial and residential property companies, non-profit organisations, public organisations such as social services and law enforcement, and contractors and suppliers. Each conference had approximately 400 attendees. Detailed notes were taken throughout each conference whenever the speakers spoke about sustainability work, no matter their organisational background. This was to get an even wider view of how the Swedish FM sector and all those who work in it tackle (social) sustainability issues in practice. These notes were then compiled as an additional data set, which was then analysed together with the interview data as one complete data set. The purpose of using the observation notes was to provide even more breadth to the data set and to anchor the interviews in wider ongoing debates in the Swedish FM sector. Therefore, the main data used in this paper were from the interviews, but the observational data helped to contextualise the interview data.

3.2 Data analysis

The data from the interviews and observations were imported into the software programme NVivo, which provides a digital platform to obtain a better overview of the data. The data were then coded according to a thematic analysis, which is an established method for analysing qualitative data and identifying and organising unexpected, detailed and rich data patterns and themes (Braun & Clarke 2006).

Data excerpts relating to social sustainability in any way were coded first, and then excerpts relating specifically to activity interventions. These codes were then labelled according to what type of activity intervention it was (e.g. leisure, employment, sports, socialising, etc.), and then sorted into categories based on the 12 indicators of Stender & Walter’s (2019) framework, which enabled more detailed patterns in the data to be identified. After several coding rounds, it was clear that the housing companies implemented different activity interventions for their tenants that corresponded well to the indicators of the theoretical framework. Not all indicators were represented equally in the empirical material due to the specific focus on activity. Finally, the frame of reference was applied to understand the wider consequences for social value creation. Table 2 exemplifies the coding structure and process.

Table 2

Coding structure and data analysis

| EXCERPT/QUOTATION | TYPE OF ACTIVITY INTERVENTION | LABEL | INDICATORS BASED ON STENDER & WALTER’S (2019) FRAMEWORK | THEME BASED ON STENDER & WALTER’S (2019) FRAMEWORK AND FRAME OF REFERENCE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘We decided to start with soccer [football] practice every Wednesday night with the more at-risk youths in the neighbourhood’ | • Organising soccer/football practice | • Sports activity | Indicator 4: Social activity | Social cohesion |

| ‘Do we only want a café where you can get a latté and a piece of pie? What can we do to create a safe place where people want to meet? | • Creating a neighbourhood café | • Socialising | Indicator 3: Meeting places | |

| ‘It’s about finding ways to communicate with our tenants […] then people come to us with fun ideas’ | • Neighbourhood get-togethers | • Socialising • Tenant influence | Indicator 8: Inclusion | Participation |

| ‘Much is about creating bustling living environments and communal areas. Communal garden cultivation has become popular in the last few years’ | • Creating communal gardens based on tenant input | • Tenant participation in development work • Socialising | Indicator 7: Participation | |

| ‘If we purchase cleaning maintenance or garden maintenance, then we have a social clause demanding that the contractors must be willing to take in tenants to work there’ | • Creating employment through social procurement | • Employment | Indicator 11: Employment and education | Accessibility |

| ‘It’s part of the social contract, that you earn your money. You feel good. Most people who are unemployed do not feel good’ | • Employment leads to personal wellbeing | • Better health | Indicator 12: Health | |

| ‘We have insurance and when cars are burning and property is destroyed, that affects our costs. There are a lot of extra costs [caused by criminal activity]’ | • Criminal activity and vandalism create additional costs | • Low social value incurs costs | n.a. | Financial gain from social value creation |

| ‘We cannot kid ourselves: this also means financial gain for the housing company. We earn money by letting our tenants do this work rather than purchasing this service from a supplier’ | • Hiring unemployed tenants to clean the building stock saves costs | • Tenant employment decrease costs | n.a. |

The empirical data were thus iteratively and abductively analysed by applying the theoretical framework and frame of reference. By abductively moving between empirical data and theory, the understanding of both was expanded (van Maanen et al. 2007). Through this organic, interpretive and intuitive abductive analysis, the codes became more refined, theoretically informed and aggregated in each round of analysis. The three themes of Stender & Walter’s (2019) framework (social cohesion, participation and accessibility) and the theme regarding financial value were used to structure the findings, which follow next.

4. Findings

4.1 Social cohesion

Most of the activity interventions for the theme of social cohesion related to indicator 4, i.e. creating social activities. The interviewees and speakers at the three conferences provided many examples of social activities they had created for their tenants. Much of it related to partnering with sports clubs to offer sports activities (e.g. soccer/football, basketball, skiing or ice-skating). Other activities had been created together with housing associations or other property owners, to host neighbourhood get-togethers, cooking lessons or waste collection days. Some activities were very simple (e.g. organised playdates in the park), while others targeted important life skills (e.g. paying the swimming school fee for children).

Having after-school programmes or sports activities was said to be a good way to provide children with meaningful leisure time after school, rather than being unproductive or causing trouble:

We offer after-school programmes for children. They were out causing trouble in the neighbourhood and we had a lot of vandalism. Now, they participate in our more sensible activities and we’ve had less vandalism.

(PubB2)

Another example was weekly soccer/football practices:

We decided to start with soccer practice every Wednesday night with the more at-risk youths in the neighbourhood. The neighbourhood manager stepped up, and he brought a property technician with him. And the two of them got to know these troublemaking, at-risk youths, and all of a sudden, things calmed down. […] Then, we hired eight of these youths to work during the Christmas break to keep the neighbourhood clean and tidy.

(Pri2C)

Social activities were thus seen as a way to create a healthy outlet for youths who engaged in sports instead of criminal activities, which was very costly for housing companies to deal with.

It was clear that many, if not most, of these activities were often created together with other actors:

We’re not the ones who are actually arranging it, but rather we make sure that it happens.

(PriC1)

If there were already an association or club leasing a space in the neighbourhood, they could get discounts on their rent if they offered services or activities for tenants. Similarly, the mode of collaboration with sports clubs had recently shifted from sponsoring them financially each year and displaying the company logo at their training facilities to being much more collaborative. Many of the interviewees explained how they still offered sponsorships to sports clubs, but that the sports clubs were now also expected to host classes and activities for tenants and participate in neighbourhood-watch activities. This more in-depth collaboration had been met with some hesitation from the sports clubs, as it required a much more comprehensive effort from their side. One interviewee described it thus: ‘We don’t have sponsorships anymore; we have collaborations’ (PubF1). This more in-depth mode of collaboration was said to give housing companies more value for money.

Housing companies also contributed considerably to indicator 3, i.e. meeting places. Many of the interviewees explained how they had been actively trying to establish new places for tenants to socialise, and offer amenities in the process. For example, the interviewees from one housing company (PubA) explained how they were trying to set up a café in the neighbourhood where local women could work, and which could be a multicultural centre for people to meet to provide extra value for the neighbourhood:

Do we only want a café where you can get a latté and a piece of pie? Or do we want to look at it from a bigger perspective? What can we do to create a safe place where people want to meet?

(PubA3)

Many of the interviewees and several of the speakers at the first industry conference talked about partnering with private actors to create more meeting places and vibrant city centres with amenities and shops, as they thought it would provide financial and social prosperity.

Creating meeting places inevitably leads to indicator 6, i.e. amenities. The collaboration with private actors to establish a café, keeping the local grocery store afloat, and hosting sports clubs, hobby associations and non-profits not only provided meeting places but also served as a type of amenity for the tenants. In these places, tenants had an option to socialise, shop and develop themselves within their own neighbourhood. By offering spaces to organisations, sports clubs and non-profits, i.e. spaces that may have previously been used for criminal activities, they were instead occupied by something positive:

In a parking lot that has been a hot spot for the drug trade for a long time, we have remodelled it into a park where we have 35 different organisations that organise activities all summer long.

(PubA2)

This also created an increased sense of safety, thereby contributing to indicator 2.

4.2 Participation

There were fewer clear contributions to theme 2 (participation), which is unfortunate as many of the tenants living in the more disadvantaged neighbourhoods, especially women, suffer from low participation and inclusion due to language barriers, unemployment and gender structures. Neighbourhood get-togethers were one way of creating a space where housing companies could increase inclusion (indicator 8) by socialising with their tenants and learn what tenants would like to see in their neighbourhood:

It’s about finding ways to communicate with our tenants, and once you open those doors and people understand that there is someone to talk to […] then people come to us with fun ideas.

(PriC2)

By including the tenants in such a way, housing companies also contributed to increased participation (indicator 7) where tenants were given the opportunity to provide input on how to shape the physical environment, e.g. when refurbishing a playground, creating communal gardens or reshaping the green areas:

Much is about creating bustling living environments and communal spaces. Communal garden cultivation has become popular, to be able to meet [neighbours] in the garden.

(PubD1)

These activities not only contribute to increased inclusion and participation but also to other indicators such as 12 (health) or 2 (safety).

4.3 Accessibility

Indicator 11 (employment and education) was the most represented indicator within the theme of accessibility. The vast majority of activity interventions were either using social procurement to demand that suppliers and service providers hire unemployed tenants, or the housing companies hired their unemployed tenants in-house to work with facilities maintenance work, green area maintenance or cleaning services; as one interviewee described it:

We have social clauses in all our contracts. So, if we purchase cleaning maintenance or garden maintenance, then we have a social clause demanding that the contractors must be willing to take in tenants to work there.

(PriC1)

Usually, the tenants were hired as interns or had fixed-term employments between three months (e.g. summer jobs) and 18 months. The idea was that these jobs should be a springboard to obtain work experience to easier join the labour market, but it was not uncommon for some of the tenants to remain at a supplier company if they performed well. These interventions are important and especially meaningful in many neighbourhoods that are socio-economically disadvantaged with a high rate of unemployment and low education levels and graduation rates among tenants. Here, many are of immigrant background with limited work experience and language proficiency, making it very difficult for them to gain employment or training in a more traditional manner.

Several housing companies also offer vocational training and career-building workshops and courses. One example of this was inviting non-profits to establish in the neighbourhood and offer coaching and classes on entrepreneurship, resumé workshops and interview skills: ‘It’s very appreciated. They create many positive forces in the neighbourhood’ (PubA1). One speaker at the third conference talked about a newly started ‘housing company academy’, which was an in-house programme to teach unemployed, young adults FM as a career. PubA had a similar initiative that targeted immigrant women. Instead of hiring external cleaning services, the housing company hired their female immigrant tenants. This was a way for them to learn Swedish, be part of a social context, learn life skills and break the isolation many of them had lived under for many years. In addition, when actual tenants were visible in the neighbourhood, the perception of safety increased. This practice was something several of the housing companies applied to varying degrees.

According to the interviewees, the tenants who were given a job also got many benefits that spilled into other indicators, such as better health (indicator 12):

That people have a job is a prerequisite for safe neighbourhoods. It’s part of the social contract, that you earn your money. You feel good. Most people who are unemployed do not feel good.

(PubB3)

Several of the interviewees and speakers at the conferences emphasised how having access to good education, and later to employment, was a key prerequisite for good health and prosperous neighbourhoods. They argued that having employment meant better mental wellbeing, that parents would be better role models for their children and be able to provide for them. Unemployment negatively affects whole families, so having employment is not only good for society, but for the tenants, their families and their neighbourhood. The interviewees also said that having tenants working in the neighbourhood was a deterrent for vandalism:

I would say that it’s cleaner in the neighbourhood because it is not as fun to vandalise and litter when your neighbour is the one picking up the trash.

(PriC1)

Having a job also meant being in a social context, which is something that many long-term unemployed tenants lacked.

The interviewees said that their educational activities were especially important. In more disadvantaged neighbourhoods, it is common for school results to be poor. In such neighbourhoods, families often live in very close quarters, meaning that there is little space or quiet to undertake homework. In response to this, several of the housing companies created hubs where children could go to study and obtain help with their homework. One of the housing companies had combined its homework support initiative with the offer of a summer job as a reward for improved school grades. Some of these disadvantaged children also went to school hungry because they did not have breakfast at home, so some of the housing companies paid for them to be given breakfast at school to improve their study results.

Engaging in this type of activity was not always easy for the housing companies. Some of their employment initiatives had been hampered by exogenous forces, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the partial dismantling of the public employment agency. Also, many of their educational and employment activities were outside their formal responsibilities:

We operate an after-school day care. We can discuss whether it’s our or the municipality’s responsibility, but if they don’t see a need for it, and we do, and we see business opportunities in it, then we do it anyway.

(PubB3)

Table 3 summarises the main findings and the interviewees’ perceived effects of implementing these activity interventions.

Table 3

Summary of the main findings

| INDICATOR | ACTIVITY INTERVENTION | PERCEIVED EFFECTS FROM INTERVENTIONS |

| Social cohesion | ||

| No. 2: Safety | • Establishing communal spaces such as gardens, refurbishing spaces for leisure, creating shared activities such as sports, tenants working in the neighbourhood | • Deters from criminal activity and creates safer living environments |

| No. 3: Meeting places | • Establishing a café and multicultural centre, communal gardens and recreational spaces | • Creating places for meeting and socialising • Increased connectedness between neighbours • Leads to new work opportunities |

| No. 4: Creating social activities | • Sports activities (e.g. soccer/football, basketball, skiing, swimming, ice-skating), neighbourhood get-togethers, cooking lessons, waste-collection activities, park playdates, swimming lessons, after-school programmes, clubs and hobby associations leasing space at discounted rents | • Offering social activities for tenants deter from criminal behaviour • Increases physical and mental wellbeing • Many of the activities require collaboration with external actors • Collaboration rather than sponsorships |

| No. 6: Amenities | • Cafés, local shops, sport clubs, hobby associations | • Opportunities for social activities and meeting places also serve as amenities and deters criminal activity |

| Participation | ||

| No. 7: Participation | • Collecting input on developing the physical environment, refurbishment projects and creating communal gardens | • Tenant participation in neighbourhood development |

| No. 8: Inclusion | • Neighbourhood get-togethers | • Increase inclusion and socialising with tenants |

| Accessibility | ||

| No. 11: Employment and education | • Social procurement to create employment and internships in suppliers, hiring tenants in-house, company-initiated vocational training programmes, career-building workshops, homework hubs with tutors, providing breakfast in school | • Tenants to gain work experience and have a springboard to the labour market • Learn life skills, improve language proficiency, break isolation • Increase safety and decrease criminality • Improve school grades and graduation rates |

| No. 12: Health | • Creating jobs, internships and vocational training | • Improve personal wellbeing and happiness |

Some of the effects of the activity interventions were unrelated to social value and the indicators prescribed by Stender & Walter (2019), but are rather related to financial effects from the social value creation, which is discussed below.

4.4 Financial gain from social value creation

By observing the speakers at the industry conferences and speaking to the interviewees, it quickly became clear that it was very difficult for housing companies to separate social value creation from financial value creation. Discussions often ended in contemplations about how these social interventions were a business opportunity that contributed to the financial bottom line and property values. Much of the discussion of social value creation was overshadowed by a very commercialised discourse where social value was expressed in monetary terms. This was perhaps unsurprising, as the interviewees explained how issues of unemployment, poor graduation rates, criminality, feelings of unsafety and vandalism negatively affected property values, interest rates to loan institutions, insurance fees and maintenance costs:

We have insurance and when cars are burning and property is destroyed, that affects our costs. There are a lot of extra costs [caused by criminal activity].

(PriC2)

This is why many of the interviewees saw social value creation as a way to avoid financial losses.

When talking about how they hired their unemployed, female immigrant tenants to undertake cleaning work in the neighbourhood, one interviewee said:

We work for equality and for these women to get power over their own lives. But we cannot kid ourselves: this also means financial gain for the housing company. We earn money by letting our tenants do this work rather than purchasing this service from a supplier. So far, the quality has also been much better.

(PubA2)

Therefore, there were many financial reasons for the housing companies to engage in social value creation, as many of them saw how activity interventions improved their property values.

Nevertheless, it was also clear from the interviews and the speakers at the conferences that engaging in these activities was not business as usual. There were also uncertainties about what value was being created, how much value was being created, and concerns that these efforts were outside their core business:

Hopefully, when a few years have gone by, this will be something that’s part of the daily management of the housing stock, and not something we do on the side, but a natural part of operations. But we’re not there yet.

(PriC1)

Many of the interviewees described how creating social value was something that drove them as individuals, that it made them emotional seeing how much happier their tenants were after getting employment, and how public housing companies should fulfil social values as part of their mission. A speaker at the third industry conference claimed that their housing company’s social fund (which allowed employees to apply for funds for social projects) had made employees more engaged and motivated. Nevertheless, although there was a clear commitment by these Swedish housing companies to creating social value (summed up as follows: ‘It’s a human right not to live in a bad neighbourhood’; PriC2), the social value creation was often reframed in terms of financial gain.

5. Discussion

This section discusses what social value has been created and how initiatives can have spillover effects on several social value indicators, as well as part three of the purpose, of how social value creation relates to financial value.

5.1 Meaningful activities and the social value they create

As this paper focuses on the social value created from activities, some indicators have been fulfilled more than others. In the first theme of social cohesion, indicator 3 (meeting places) and indicator 4 (social activities) are the areas where by far the most value has been created. The second theme, participation, is generally underrepresented, although Gustavsson & Elander (2016) argue that employment is a form of participation in itself. The third theme, accessibility, is the most represented—especially indicator 11 (employment and education).

Elander & Gustavsson (2019) report that educational and employment initiatives are a common way for Swedish housing companies to create social value. In addition to the value created from such activities, there are also interdependencies and spillover effects between indicators, e.g. indicator 2 (safety). Requiring sports clubs to conduct neighbourhood-watch activities, deterring youths from criminal activity through sports, and making parking lots into playgrounds to promote socialising instead of drug trade are all examples of how contributing to indicator 4 (social activities) and indicator 3 (meeting places) has also helped contribute to indicator 2 (safety). The creation of hobby spaces, communal gardens and cafés has also provided meeting places for tenants to come together, as in indicator 3, whilst also providing amenities for tenants, as in indicator 6. Furthermore, the interviewees said that having good schools and employment was a prerequisite for safe neighbourhoods, so indicator 11 (employment and education) has had spillover effects on indicator 2 (safety) as well. An implication of these spillover effects and the collaboration that goes into them likely also leads to more active, close-knit and connected communities.

Therefore, positive activities such as homework support, sports or summer jobs, can deter from negative activities such as criminality or vandalism, i.e. soccer/football practice can deter from selling drugs, and job creation is a way to reduce crime. As such, many of the activity interventions the housing companies initiated have created much more social value than first thought. Also, an implication of all these positive changes is their contribution to indicator 1 (identity). Previous research (Robertson et al. 2010; Gustavsson & Elander 2016) shows how important it is for people’s sense of wellbeing to live in a neighbourhood with a positive identity, so these spillover effects into indicator 1 may be the most important of all.

The findings also provide an insight into where social value creation may have the greatest effect. Although this study does not focus exclusively on housing companies in disadvantaged neighbourhoods, most of the examples brought up by interviewees and conference speakers were from more disadvantaged neighbourhoods. The likely reason for this is that these areas are where activity interventions create the most value and the need for them is greatest. Creating jobs in neighbourhoods with low levels of criminality and high levels of employment would likely have a negligible benefit.

An implication of these activity interventions is that they require continued commitment and resources from housing companies to sustain long-term effects. For example, employments and internships offered to tenants are often temporary, and although some move on to permanent employments, this is not guaranteed for everyone. Also, as youths grow up and pass through the school system, continuous educational activities must be maintained. Although these activity interventions can have positive long-term effects, they are temporary in nature, in comparison with, for example, initiatives that contribute to environmental sustainability. Building with green materials or using green technologies are one-off efforts that have long-term positive effects because they do not need to be upgraded for 20–30 years. Social initiatives must run continuously as people grow, change, and move in and out of the neighbourhood. This is why activity interventions and other social sustainability practices must become business as usual to ensure their longevity.

5.2 Social value in relation to financial value

It was interesting how social value creation led to collaborations with other organisations. Similarly, Loosemore et al. (2021) report how collaborative partnerships between different types of organisations were necessary for social procurement in Australia. Previously, the housing companies’ relationships with sports clubs, associations or non-profits were simple sponsorships in return for putting up the company’s logo and as a way of getting goodwill. Now, these relationships have become more complex, demanding that sponsored organisations offer leisure activities, classes or workshops to tenants. An implication of this more in-depth exchange is a new type of business model that is more commercially informed than before, where housing companies leverage their power to truly get value for their money in the form of more social value creation. These activity interventions have thus affected how the business is run, and can hopefully encourage housing companies to wisely leverage their power to create even more social (and financial) value in their FM operations.

There was an overemphasis on the financial bottom line when discussing social value, e.g. how hiring tenants provided a cheaper cleaning service with higher quality results or how vandalism made neighbourhoods more expensive to maintain. Nevertheless, activity interventions are costly for housing companies. Previous research (Troje & Gluch 2020; Loosemore et al. 2021) reports that it drives up costs in terms of time, resources and training for staff who supervise new employees. In addition, creating jobs and providing homework support or leisure activities for tenants is outside housing companies’ formal responsibilities and core mission of providing housing (Fujiwara 2013; Troje 2023). It is reasonable for housing companies concerned with their financial bottom line to question such costly activities, but it is also possible that the alternative cost is greater. Unemployed tenants relying on welfare to pay rent, criminality resulting in lower property values and higher interest rates from loan institutions, and vandalism that increases maintenance costs are all issues that negatively impact the bottom line and are likely costlier than activity interventions.

Considering that the discussions about social value creation tended to end up in discussions about financial gain, one could wonder if these interventions are a weaker form of ‘whitewashing’, in the sense that they are not necessarily performed to create social value, but to gain financial value and as a form of risk management. It is then reasonable to ask whether these housing companies would have engaged in these activities if they did not provide financial gain, and what the true motivation behind social sustainability work really is. Perhaps the main intentions underlying the activity interventions are unproblematic, though research suggests housing companies are becoming increasingly profit-driven and that unsustainable practices are increasingly window-dressed as sustainable (Grander 2017; Stender & Walter 2019). The interviewees all expressed non-financial motivations for engaging in social value creation (e.g. it was important to them personally, it was part of public housing companies’ mission to fulfil public values), but would such efforts end if they were not profitable? Nevertheless, despite the commercialised shift in Swedish housing companies, it seems the pursuit of both social and financial value remains positively and mutually reinforcing, much like Maine et al. (2022) suggest.

5.3 Contributions

This paper makes several contributions to housing research, to social sustainability research and to practice. For housing research, it contextualises and exemplifies how housing companies can contribute to a more socially sustainable built environment. It also shows how local initiatives, such as creating jobs or social activities, provide value for individual tenants, the local neighbourhood, the housing company and society at large. The paper also provides an insight into how social value creation can actually be an important way for housing companies to create financial value. It also highlights a phase of a building’s life cycle (FM/operations) that is often overlooked in studies of social sustainability (Raiden et al. 2019), and the many opportunities for social value creation this phase provides. Lastly, the paper emphasises the least prioritised pillar of sustainability, the social pillar, in a housing context (Stender & Walter 2019).

For social sustainability research generally, and Stender & Walter’s (2019) framework in particular, the paper shows how activity interventions create social value for employees of housing companies, which is something the framework does not cover. One interviewee described how they got very emotional when they realised how much the company’s efforts meant to the tenants. Another interviewee described how an area manager had started playing soccer/football every week with a group of at-risk youths, while another explained how their employees had become more motivated and engaged since establishing a fund for social projects. Doing this type of work thus has positive effects for others beyond those living in the neighbourhood. Troje & Gluch (2020) and Loosemore et al. (2021) have drawn similar conclusions about social procurement. As such, the framework could be extended to include the social value created for those working in or in relation to the neighbourhood, and not only for those living there. The paper also illustrates how different indicators are interdependent in terms of spillover effects between indicators, which shows the embedded nature of social value creation in housing.

Lastly, for practitioners, the paper adds to the body of work on housing management and provides evidence in favour of a type of practice (activity interventions) that has identifiable benefits to residential communities. Hopefully, this can encourage more of such interventions in the future. This paper clearly outlines where the activity interventions add most value, and for whom, both directly and through spillover effects. This can help housing companies make more informed decisions about their social value activities and target certain areas or activities that provide the most value for their neighbourhoods’ specific needs. By understanding what activities create social value, it is possible to design new solutions and practices that contribute to fulfilling the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and create a more equitable future for all.

5.4 Limitations and future research

Several limitations in this paper can be addressed in future research. The qualitative research design is interpretive and contextually sensitive. However, it cannot capture an entire population and generalisability is more difficult. Due to its qualitative research design, the paper makes no attempt to quantify social value in monetary terms, but instead examines the qualitative effects of social value creation. To complement this paper, future research could quantify social value creation by applying methods such as cost–benefit analysis or social return on investment. This may be especially important for practitioners and policymakers wanting to make a case for activity interventions and similar social value practises.

Although the geographical scope of this study was Sweden, the findings support much of what has been found in international research. The findings are likely applicable to other Western European contexts or developed countries that share similar institutional features: legislation, developed economies and housing markets. Future studies of international examples could compare interventions in different contexts.

The present research only takes into account the perspectives of those working in housing companies and their perception of value creation. Future studies should add the perspectives of tenants and other organisations active in the neighbourhoods.

Many activity interventions discussed in this paper are related to crime reduction and prevention. A deeper understanding of the relationship between crime prevention and social value creation could draw on the field of environmental criminology (Wortley & Townsley 2016).

6. Conclusions

A wide range of employment, educational and leisure activities has been created by housing companies for their tenants in order to create social value. The areas in which these interventions have the most social impact were illustrated and found to be a form of risk management to mitigate issues related to criminality, welfare-dependent tenants and decreased property values. Although these interventions are performed by housing companies to create social value, an important underlying purpose (and benefit) is often to minimise housing companies’ financial losses.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the interviewees for providing their time for this study.

Competing interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

Data availability

The data set is in Swedish and not available to others in order to ensure the anonymity of the interviewees.

Ethical consent

The study participants provided written consent to be interviewed at the time of the interview request, and later confirmed this approval orally at the time of the interviews. According to the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (www.etikprovningsmyndigheten.se), further external ethical approval is not required for the type of non-sensitive data acquired in this study, as it only relates to a person’s work and not their personal life or personal opinions.

Funding

The study did not receive any external funding.