Breast cancer (BC) and ovarian cancer (OC) account for a substantial proportion of cancer-related deaths worldwide. Germline pathogenic variants in the known BC/OC predisposition genes are responsible for approximately 6–10% of BC and 18–29% of OC patients.[1] These genes are crucial in maintaining genomic stability through the homologous recombination-mediated DNA repair pathway.[1] Among the genes involved in this pathway, RAD51 paralog D (RAD51D) has been reported as a BC and OC vulnerability gene among Caucasians.[2] Subsequent studies in both Asian and Caucasian populations have confirmed these findings, though they have reported considerable variability in the frequencies of pathogenic RAD51D variants. A recent meta-analysis and the Cancer Risk Estimates Related to Susceptibility (CARRIERS) consortium study reported pathogenic RAD51D variants in 0.41% (94/22,787) of OC patients[3] and 0.09% (36/38,332) of BC patients.[4]

Individuals harboring pathogenic RAD51D variants face lifetime risks of 20-44% and 13–36% of developing BC and OC, respectively, depending on their family history of these cancers.[5] Considering these risks, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) has recommended surveillance and risk-reducing strategies for BC and OC management in individuals harboring pathogenic RAD51D variants, such as annual mammograms starting at age 40 and risk-reducing salpingooophorectomy at age 45-50 (NCCN Guidelines V3.2023). However, the successful implementation of optimal genetic testing and risk management strategies in BC/OC patients necessitates comprehensive data on the prevalence and significance of pathogenic RAD51D variants in different populations.

In Pakistan, limited data exist regarding the genetic variability of RAD51D. Notably, pathogenic variants in high-risk genes such as BRCA1, BRCA2, and TP53, along with the moderate-risk genes RAD51C, CHEK2, PALB2, and RECQL, collectively explain only 27% of young or familial BC/OC patients.[6] Therefore, to address this knowledge gap, we aimed to investigate the prevalence of RAD51D variants in 371 BC and/or OC patients from Pakistan, who had previously tested negative for pathogenic variants in BRCA1/2, TP53, CHEK2, RAD51C, PALB2, RECQL, and FANCM. All RAD51D variants identified in study cases were further screened in 400 Pakistani female controls.

For this study, we selected index patients from 371 BC/OC families enrolled at the Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital and Research Centre (SKMCH&RC), Lahore, Pakistan, between June 2001 and January 2012. All these patients were either presented with invasive BC or epithelial OC, further categorized into six risk groups as previously described.[7] All these patients were previously screened and confirmed not carrying BRCA1/2 and PALB2 small-range pathogenic variants, as well as BRCA1/2 large genomic rearrangements.[7,8] Most of these patients were also not harboring pathogenic variants in CHEK2 (n = 346), RAD51C (n = 346),[9] RECQL (n = 187),[6] FANCM (n = 154), and TP53 (n = 97). Notably, the patients presented with BC and OC in the same subject were considered as two standalone cases. The tumors of the BC patients were assessed for estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) expression by immunohistochemical analyses as described previously.[7]

In the control group, 400 Pakistani healthy women were included having no BC or OC in themselves or in their blood relatives. These women were identified from the SKMCH&RC repository of unaffected controls registered in a case–control study, as described elsewhere.[7] The study received ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of SKMCH&RC. Before the collection of blood samples, each research subject provided written informed consent.

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional and/or National Research Committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the IRB of SKMCH&RC (IRB approval numbers Date: June 01, 2001/No. ONC-BRCA-001 and Date: May 05, 2006/No. ONC-BRCA-002). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

The entire coding sequence of RAD51D (Genbank accession number NM_002878.3) along with exon-intron junctions was tested in the 371 BC/OC patients using denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography (DHPLC) analysis on the WAVE 4500 DNA Fragment Analysis System (Transgenomics, Omaha, NE). DNA amplification was performed using previously reported primers.[2,10] The set-up of amplification reactions, thermal cycling profiles, and DHPLC analysis settings can be provided on request. DNA samples exhibiting variant DHPLC elution profiles were subjected to bidirectional sequencing using a programmed 3500 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The RAD51D variants identified in the cases were subsequently screened in the 400 control samples.

Novel RAD51D variants (n = 2) previously described variants of uncertain significance (VUS) (n = 2), an unclassified variant (n = 1), and a variant with conflicting interpretation (n = 1) were assessed using in silico analysis algorithms. The functional impact of missense variants was assessed using five individual web tools, as previously described.[7] In addition, three meta-prediction tools, including Combined Annotation-Dependent Depletion (CADD) (https://cadd.gs.washington.edu/), Rare Exome Variant Ensemble Learner (REVEL) (https://sites.google.com/site/revelgenomics), and BayesDel (https://fengbj-laboratory.org/BayesDel/BayesDel.html), were also utilized.[11] These tools predicted the consequences of missense variants on the protein based on: (i) Evolutionary conservation of amino acids among different species (SIFT and Align-GVGD), (ii) alterations in protein structure and function (PolyPhen-2, MutPred, and SNAP2), and (iii) several computational, mathematical, and biochemical parameters from genomic and proteomic databases (REVEL, CADD, and BayesDel). Non-coding variants were assessed for likely splicing impact using splice prediction tools through the Alamut software user interface (Interactive Biosoftware) with default parameters.[7] The predictions by these tools are primarily based on the alterations caused by the variant of interest in sequence patterns at spliceosome binding sites. The variants were categorized in accordance with the standard variant classification criteria described previously.[12]

Of the 371 study cases, 181 (48.8%) were young BC (≤30 years of age), 127 (34.2%) BC patients were from the families having two or more BC patients with at least one of them diagnosed ≤50 years of age, 23 (6.2%) patients belonged to families with both BC and OC, 22 (5.9%) belonged to OC only families, and 18 (4.9%) were male BC patients diagnosed at any age [Table 1]. Of the 343 BC patients, 104 (30.3%) exhibited the triple-negative BC (TNBC) phenotype. The mean age of disease diagnosis was 33.7 years (range 19–73 years) for female BC (n = 325), 50.2 years (range 30–73 years) for male BC (n = 18), and 35.3 years (range 22–60 years) for OC (n = 35) patients. Among the female BC patients, 9.8% (32/325) were presented with bilateral BC.

Frequency of RAD51D VUS according to family structure

| Phenotype of families | No. of families | Families with RAD51D VUS, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| All families | 371 | 3 (0.8) |

| Early-onset BC (1 case ≤30 years) | 181 | 2 (1.1) |

| Familial BC (≥2 cases, ≥1 diagnosed≤50 years) | 127 | 1 (0.8) |

| BC and OC (≥1 BC and≥1°C) | 23a | 0 (0) |

| OC (>1°C <45 years) | 22 | 0 (0) |

| Male BC (1 case diagnosed at any age) | 18 | 0 (0) |

| TNBC status | ||

| TNBC | 104 | 0 (0) |

| Non-TNBC | 224 | 3 (1.3) |

| Unknown | 15 | 0 (0) |

BC: Breast cancer; OC: Ovarian cancer; TNBC: Triple-negative breast cancer; VUS: Variants of uncertain significance.

BC and OC in the same patient were considered as two standalone cases. This number includes index patients diagnosed with female BC (n=10), BC and OC (n=7), and OC (n=6)

In total, nine unique heterozygous RAD51D variants were detected, including four missense variants (p.Pro10Leu, p.Arg165Gln, p.Ile311Asn, and p.Ser320Asn), four intronic variants (c.83-16C>T, c.144+33G>C, c.481-26_-23delGTTC, and c.481- 7G>T), and one silent variant (p.Ser78Ser). Of these, two non-coding variants (c.83-16C>T and c.481-26_-23delGTTC) were novel and exclusively detected in the Pakistani population, while the remaining seven variants have been reported in other populations or observed in various databases including ClinVar, LOVD, or gnomAD [Table 2].

RAD51D germline variants identified in breast/ovarian cancer patients from Pakistan

| Location | Coding (c.) DNA Sequencea (amino acid change) | SNP ID | Effect | Prevalence, n (%) | Minor allele frequency, n (%) | Reference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases n=371 | Controls n=400 | Cases n=742 | Controls n=800 | gnomADd, South Asians | |||||

| Variants of uncertain significance | |||||||||

| Exon 1 | c. 29C >T (p.Pro10Leu)b | rs759505297 | Missense | 1 (0.27) | 1 (0.25) | 1 (0.14) | 1 (0.13) | 12/30606 (0.04) | ClinVar |

| Intron 5 | c. 481-26_-23delGTTCb | - | Intronic | 1 (0.27) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.14) | 0 (0) | - | Novel |

| Exon 10 | c. 932T >A (p.Ile311Asn)b | rs145309168 | Missense | 1 (0.27) | 1 (0.25) | 1 (0.14) | 1 (0.13) | 9/30616 (0.03) | ClinVar, LOVD |

| Benign variants | |||||||||

| Intron 1 | c. 83-16C >Tb | - | Intronic | 0 (0) | 1 (0.25) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.13) | - | Novel |

| Intron 2 | c. 144+33G >Cb | rs28363260 | Intronic | 1 (0.27) | 5 (1.25) | 1 (0.14) | 5 (0.63) | 222/30606 (0.73) | gnomAD |

| Exon 3 | c. 234C >T (p.Ser78Ser)c | rs9901455 | Silent | 38 (10.2) | 74 (18.5) | 38 (5.12) | 74 (9.25) | 2632/30616 (8.60) | ClinVar, LOVD |

| Intron 5 | c. 481-7G>Tc | rs145832514 | Intronic | 1 (0.27) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.14) | 0 (0) | - | ClinVar |

| Exon 6 | c. 494G >A (p.Arg165Gln)c | rs4796033 | Missense | 93 (25.1) | 112 (28.0) | 93 (12.53) | 112 (14.0) | 4896/30028 (16.3) | ClinVar, LOVD |

| Exon 10 | c. 959G >A (p.Ser320Asn)b | rs763683070 | Missense | 0 (0) | 1 (0.25) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.13) | 1/30600 (0.003) | ClinVar |

LOVD: Leiden Open Variant Database; SNP: Single nucleotide polymorphism.

Nomenclature follows Human Genome Variation Society (HGVS) (http://www.hgvs.org). Numbering starts at the first A of the first coding ATG (located in exon 1) of NCBI GenBank Accession NM_002878.3.

Predicted by in silico analyses.

Previously classified variant in ClinVar database.

gnomAD: Genome Aggregation Database v2.1.1 (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/), date accessed July 26, 2023

Three coding variants already reported in ClinVar as VUS (p.Pro10Leu, p.Ile311Asn, and p.Ser320Asn) were evaluated for their functional impact using in silico tools [Table 3]. Of these, two missense variants (p.Pro10Leu and p.Ile311Asn) were categorized as VUS according to the standard variant classification guidelines [Table 3]. Three non-coding variants, including two novel variants (c.83-16C>T and c.481-26_-23delGTTC) and a previously reported unclassified variant (c.144+33G>C), underwent in silico analysis for their potential splicing effect [Table 4]. Of these, one intronic variant (c.481-26_-23delGTTC) was categorized as VUS according to the standard variant classification guidelines [Table 4]. The remaining two non-coding variants and one coding variant were classified as benign.

In silico analyses of RAD51D coding variants identified in breast/ovarian cancer patients from Pakistan

| Coding variants | Individual in silico prediction tools | In silico meta-prediction toolsa | Classification | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PolyPhen-2 | SIFT | Align GVGD | MutPred | SNAP2 | REVEL | CADD | BayesDel | ||

| c. 29C >T (p.Pro10Leu) | Probably damaging | Deleterious | C65 | Disease | Disease | Benign | Benign | Benign | VUS |

| c. 932T >A (p.Ile311Asn) | Probably damaging | Deleterious | C0 | Disease | Disease | Benign | Benign | Benign | VUS |

| c. 959G >A (p.Ser-320Asn) | Benign | Tolerated | C0 | Polymorphism | Neutral | Benign | Benign | Benign | Benign |

VUS: Variant of uncertain significance

Cutoff scores of BayesDel with noAF >0, CADD phred-scaled>25, and REVEL>0.50 is considered as pathogenic

In silico analyses of RAD51D non-coding variants identified in breast/ovarian cancer patients from Pakistan

| Non-coding variants | Splice-site predictionsa | Classification | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SpliceSite Finder-like | MaxEntScan | NNSPLICE | Gene Splicer | HumanSplice Site Finder | ||

| c. 83-16 C>T | NE | A (0→5.3) | NE | NE | NE | Benign |

| c. 144+33G >C | NE | A (3.2→5.6) | NE | A (1.0→3.4) | NE | Benign |

| c. 481-23_-26delGTTC | A (0→85.1) | A (0→8.2) | A (0→1.0) | A (0→9.2) | A (0→88.4) | VUS |

A: Acceptor-site; NE: No effect; VUS: Variant of uncertain significance

>20% change in score (i.e., a wild-type splice-site score decreases, and/or a cryptic splice-site score increases) is considered as significant

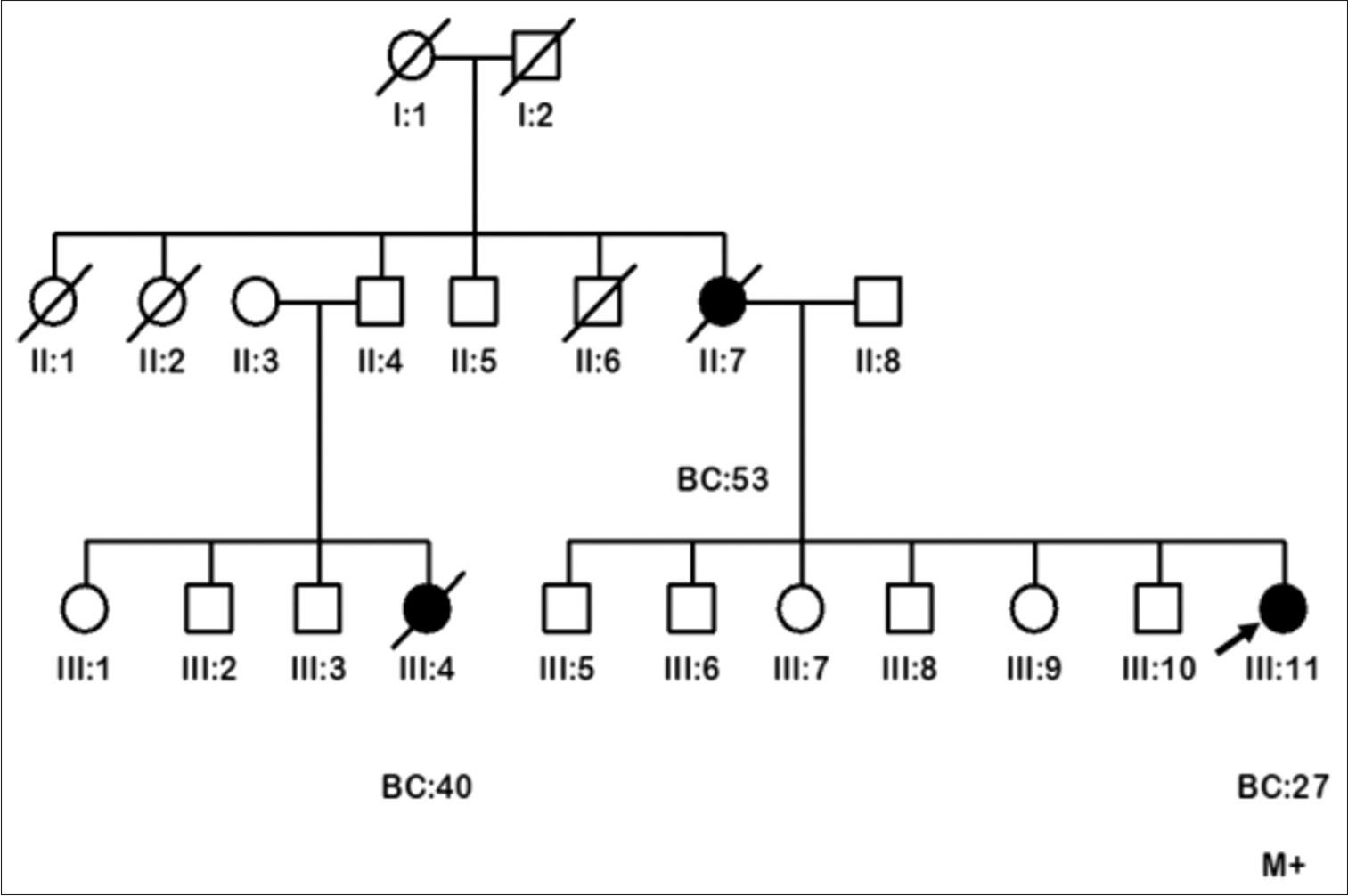

The missense variant, p.Pro10Leu, was detected in a 28-year-old female BC patient [III:11, Figure 1] of Punjabi ethnicity. She was diagnosed with grade III, lymph node-involved invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) with positive staining of ER and PR but negative for HER2 expression. The index patient’s mother [II:7, Figure 1] and a maternal cousin [III:4, Figure 1] were also presented with BC at ages 53 and 40, respectively. This variant was also detected in one out of the 400 (0.25%) healthy controls who reported that her daughter was diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. This variant was categorized as deleterious by all five in silico tools and benign by all three meta-prediction tools. The minor allele frequency of this variant is low (0.04%; 12/30606) among South Asians in the gnomAD. Based on these results, p.Pro10Leu was categorized as a VUS.

Pedigrees of the breast cancer family (FP:532) carrying RAD51D p.Pro10Leu variant of uncertain significance. Circles are females, squares are males, and a diagonal slash indicates a deceased individual. Filled symbols show cancer diagnoses. Identification numbers of individuals are below the symbols. The index patient is indicated by an arrow. BC: Breast cancer. The numbers following this abbreviation indicate age at cancer diagnosis. M+: Variant carrier

Another missense variant, p.Ile311Asn, was found in a female BC patient diagnosed at age 29 of Punjabi ethnicity. She presented with grade III, lymph node-negative IDC, expressing ER but negative for PR and HER2, having no blood relative affected with BC/OC or other cancer. This variant was also detected in one out of the 400 (0.25%) healthy controls who reported that her daughter was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s disease at age 14. This variant has conflicting interpretations in ClinVar and has a minor allele frequency of 0.03% (9/30616) among South Asian populations in gnomAD. It was anticipated as disease-causing by four of the five different in silico prediction tools and benign by all three meta-prediction tools. Based on standard variant classification criteria, it was classified as VUS.

A novel non-coding variant, c.481-26_-23delGTTC, was identified in a female BC patient diagnosed at age 30 of Punjabi ethnicity. She was diagnosed with grade III, lymph node-involved IDC with positive staining of ER, PR, and HER2. This nucleotide alteration was not detected in the 400 healthy females and was also absent in the literature or various databases including ClinVar, LOVD, and gnomAD. It was identified to initiate a novel splice-xsxsxsxsacceptor site and abolish the natural acceptor site by all five splice-site prediction algorithms. Based on these in silico estimations and the absence of this variant in the control population, c.481-26_-23delGTTC was classified as a VUS.

In the present study, we conducted a comprehensive screening of the RAD51D and did not identify any pathogenic variants in the 371 Pakistani high-risk BC and/or OC patients. However, three VUS were identified with a frequency of 0.8% (3/371) in this study cohort. A previous retrospective study from the southern region of Pakistan reported one pathogenic RAD51D variant (p.Arg300*) in 0.4% (1/273) of BC patients using a multigene panel on a next-generation sequencing platform.[13] The differences in findings may be attributed to variations in study populations, criteria for patient selection, and variants screening approach. The study participants were selected based on age at BC diagnosis (<50 years), TNBC phenotype, or affected relatives with breast, ovarian, pancreatic, and prostate cancer (NCCN 2016 version 1.2016 genetic testing criteria). In contrast, our study specifically focused on young or familial BC/OC patients from the central and north-west regions of Pakistan, and we performed RAD51D variant screening using DHPLC and subsequent bidirectional DNA sequencing. Of note, Akbar et al. also reported a likely-pathogenic missense variant (p.Ser207Leu) in a 55-year-old female BC patient who also carried a pathogenic FANCM variant.[13] Our study results align with another study on 84 sporadic BC patients from the southern region of Pakistan that has similarly not detected any pathogenic RAD51D variants using a next-generation sequencing platform.[14] These findings suggest a minimal association of pathogenic RAD51D variants with BC/OC risk in the Pakistani women.

Our study findings are consistent with other studies that have not identified pathogenic RAD51D variants in BC and/or OC patients from various populations, including India,[15] Taiwan,[16] Finland,[17] and France.[18] However, it is important to acknowledge that pathogenic RAD51D variants have been reported in Asian and Caucasian BC/OC patients, with a prevalence varying from 0.1% (6/5589) to 2.9% (3/105) in different studies.[10,19–22] The variations in reported frequency across ethnicities, geographical locations, and study populations emphasize the importance of studying genetic diversity in different populations to better understand BC susceptibility.

In the present study, one RAD51D missense variant, p.Pro10Leu, was detected in a familial BC patient and in one out of the 400 healthy controls, where the control subject’s daughter was diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. The co-segregation analysis of this alteration with BC in the index patient’s mother and a maternal cousin was not possible as these relatives were deceased at the time of the index patient’s enrollment. This variant is in an extremely conserved N-terminal domain (residues 1–83) of RAD51D, essential for single-stranded DNA-specific binding and protein-protein interaction with XRCC2 involved in homologous recombination repair.[23] It has been reported as a VUS in ClinVar and has a low minor allele frequency among South Asians in gnomAD. In silico prediction tools predicted it as deleterious by all five tools and benign by all three meta-prediction tools. This variant was previously reported as a VUS in BC/OC patients (1/1010; 0.1%) from India[19] and in individuals with Lynch syndrome-associated cancer and/or colorectal polyps (1/1260; 0.08%) from the USA.[24] These findings suggested classifying the p.Pro10Leu variant as a VUS.

Another missense variant, p.Ile311Asn, was detected in a young BC patient and in one out of the 400 healthy controls, where the control subject’s daughter was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s disease. This variant lies in a highly conserved nucleotide in the ATPase domain (residues 78–328) of the RAD51D protein that interacts with XRCC2 and RAD51C for efficient homologous recombination repair.[23] This variant was projected as disease-associated by four of the five different in silico estimation tools. It has been reported with conflicting interpretations in ClinVar and has a low minor allele frequency among South Asian populations in gnomAD. Previously, this variant was reported as a VUS in multiple studies on BC and/or OC patients from China,[20] Taiwan,[16] Greece, Romania, and Turkey,[25] gastric cancer patients from Italy,[26] and unselected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma patients of Asian origin.[27] Based on the location of this alteration, in silico prediction, and clinical data, p.Ile311Asn was categorized as a VUS.

Our investigation has some limitations that need to be acknowledged. First, the use of DHPLC as a pre-sequencing variant screening method, with a sensitivity of <100%, may have resulted in the possibility of missing some pathogenic variants, potentially leading to an underestimation of the reported pathogenic variants in this study. Nevertheless, DHPLC is a valuable method for mutation scanning of hereditary cancer susceptibility genes,[28] as it has been used for comprehensive RAD51D variants screening[10] and recently for BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants screening in breast and/or ovarian cancer patients.[29] Second, functional analyses were not performed for the identified VUS which limits our ability to definitively assess their pathogenicity. The c.481- 26_-23delGTTC variant carrier was deceased; at the time, this study was conducted, hampering the RNA analysis to validate the potential effect of this variant on RNA splicing. Third, the limited number of OC patients (n = 35) in our study cohort, combined with the known association of RAD51D with OC risk, might have led to an underestimation of the prevalence of RAD51D disease-causing variants in our study.

In conclusion, our study did not identify any pathogenic RAD51D variants in the 371 young or familial Pakistani BC/OC patients. However, we identified three VUS (3/371; 0.8%) in this study cohort. Our findings suggest that RAD51D variants play a marginal role in BC/OC risk in the Pakistani women. Functional studies are suggested to better understand the impact of RAD51D on BC and OC susceptibility in this population. Understanding the genetic landscape of RAD51D in different populations is crucial for better risk assessment and managing BC and OC patients worldwide.