The World Health Organization (WHO) notes that most individuals requiring palliative care prefer to stay at home, underscoring the importance of delivering palliative care within the community as an integral part of primary healthcare (1). The research done in Slovenia supports this WHO indication (2, 3). The primary palliative care team in Slovenia includes a family physician and a nurse; sometimes also administrative support (4). The family physician (FP), as the leader of the interdisciplinary primary care palliative team, is expected to play a crucial role in decision-making, coordination and monitoring of care, aligning with the needs of patients and their families, and facilitating connections with specialised palliative care when necessary (5). A good start is crucial; preferably, this would begin with a family meeting that involves patients, their family and healthcare professionals (6). Early research on family meetings in critical care settings (7, 8) laid the groundwork for the approaches favored by palliative care providers today. This structured gathering includes the patient, their family and healthcare professionals. The meeting’s purpose is to exchange information and concerns, clarify care goals, discuss diagnosis, treatment and prognosis, and prepare an advanced care plan (9). One of the models that helps facilitate a family conference is the 7-step family conference framework (10). Effective family meetings require clear and honest communication (11), and it is advisable to involve the patient in choosing topics (12), as the patient’s most important concerns often differ from what doctors expect to be important (13). To build trust and establish a collaborative partnership between the patient and the physician, it is also necessary to consider the emotional dynamics of the relationship and empathetically align with the patient (14, 15). Finally, team composition is crucial; an interdisciplinary group of experts, including physicians, nurses and social workers, leads to a more qualitative discussion (7, 11, 16). The Clinical Practice Guidelines for Conducting Family Meetings in Palliative Care involve three steps: preparation, meeting and follow-up (17). In preparation, the meeting’s purpose is introduced, key family members are identified and patient permission is sought. During the meeting, ground rules are set and information is exchanged. Followup includes documenting decisions, sharing information and initiating follow-up with the primary caregiver (17). Experiences from hospital clinical practice highlight numerous benefits of family meetings (7, 16, 18); they are recognised as best practice in placing the patient and their family at the centre of care (7). The main barriers to integrating family meetings into daily practice include inadequate communication skills, time constraints, unrecognised emotional needs, role ambiguity and lack of reimbursement (7, 19, 20). In Slovenia palliative home visits (described as visiting a terminally ill patient at their residence and initiating symptomatic therapy) and team consultations (which involve a physician collaborating with experts from other institutions, such as social work centres) are reimbursed by the insurance company (21). A low reimbursment is also provided for the recorded discussions with district nurses, the mobile palliative team, or patients during clinic visits (21). Training in family meetings is part of palliative medicine education, which is increasingly present during undergraduate education in Slovenia (22-24). More extensive training (theoretical and practical) is integrated into postgraduate family medicine specialisation training (25). Our research is the first of its kind in Slovenia to explore the conduct of family meetings at the primary care level and the obstacles that hinder their implementation.

We conducted semi-structured qualitative interviews with FPs and FP trainees. Participants were purposively sampled. We invited FP specialist and resident physicians via email or in person and shared the invitation in the Facebook group ‘Family Medicine Residents,’ which has 460 members. The inclusion criteria were working at the primary care level and consenting to participate in the study; physicians who do not conduct family meetings were excluded. Fourteen physicians met the criteria in the initial sampling round. As saturation had not yet been reached, the additional participants were recruited using snowball sampling. All participants received a study description and a consent form via email, which they signed prior to the interview. Verbal consent was also obtained before each interview.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted in person, over the phone, or via a web-based video conferencing platform by one researcher (M.B.) trained in interviewing methodology during the trainee programme. All interviews were completed between September 2023 and December 2023. Questions were designed to elicit challenges in providing family meetings in primary palliative care, potential barriers and facilitators to a proactive approach in family medicine, and suggestions for optimising the implementation of family meetings in existing workflows. Demographic and practice-related information was selfreported by participants, including gender, training background and age. The sample size was guided by an interim assessment of interview data for thematic saturation, which was reached within 16 interviews (26).

Lincoln and Guba established strict criteria for trustworthiness in qualitative research: credibility, dependability, confirmability and transferability, known as the “Four-Dimensions Criteria” (FDC) (27). Other studies have used variations of these categories to ensure rigour (2830). In our study, we systematically adapted these criteria by selecting applicable strategies, as shown in Table 1.

Key FDC strategies adapted from Lincoln and Guba.

| Rigour criteria | Purpose | Original strategies | Strategies applied in our study to achieve rigour |

|---|---|---|---|

| Credibility | To ensure the results are accurate, credible and trustworthy from the participants’ perspective. |

| The interview protocol was tested during two induction meetings and through 1-2 pilot interviews. |

| Dependability | To ensure the findings of this qualitative inquiry are replicable within the same cohort, coders and context. | Thorough description of the study methods | We prepared detailed drafts of the study protocol and participants’ infromation. |

| Confirmability | To strengthen confidence that the results would be validated or confirmed by other researchers. | Triangulation | We applied the following triangulation techniques: data source, investigators, theoretical. |

| Transferability | To enhance the extent to which the results can be generalised or applied to other contexts or settings. | Purposeful sampling | We used intensity sampling and maximum variation sampling. |

The analysis followed the Framework Method (311–33), which is part of the thematic analysis family and emphasises identifying patterns and contrasts in qualitative data while exploring relationships between different elements. Interview transcripts for each participant were reviewed and consolidated into a matrix organized by broad themes, categories and codes related to family meetings in family medicine palliative care.

This method facilitates the derivation of descriptive and explanatory conclusions centered on key themes.The analytical process included the following steps:

Familiarisation: Each transcript was carefully read to immerse the research team in the data, capturing initial impressions and key points.

Indexing and Coding: Transcripts were systematically coded, with codes derived both inductively (emerging from the data) and deductively (informed by the research objectives and interview guide).

Matrix Development: Codes were organized into a matrix to allow comparison across cases and to facilitate the identification of patterns.

Theme Construction: Themes were constructed by clustering related categories, focusing on relationships within the data to ensure both descriptive accuracy and interpretative depth.

Consensus and Refinement: Three research team members (M.B., E.Z., L.J.K.) held regular online meetings to iteratively review transcripts and refine the themes, categories and codes. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion until consensus was achieved.

Representative quotations were extracted to illustrate categories and ensure transparency and the grounding of findings in participants’ accounts. Used rigour criteria are presented in Table1. Reporting of qualitative results follows the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) (33–35). This structured approach ensured that themes and codes were actively constructed and reflected both the depth and breadth of the data, rather than merely summarising surface-level content. Ethical approval to conduct the study was obtained from the National Medical Ethics Committee of the Republic of Slovenia (NMEC), No. 0120-188/2023/3.

A total of 16 interviews were conducted among 2 trainees and 14 specialists of family medicine (Table 2). The average age was 44.19 years (with the median age of 41 years, interquartile range 13.5). Interviews lasted up to thirty minutes.

Participants’ characteristics (n=16).

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Female Gender | 13 (81.3) |

| Male gender | 3 (18.7) |

| Trainee | 2 (12.5) |

| Working only in nursing home (NH) | 5 (31.25) |

| Working only in general practice (GP) | 6 (37.5) |

| Working in NH and GP | 5 (31.25) |

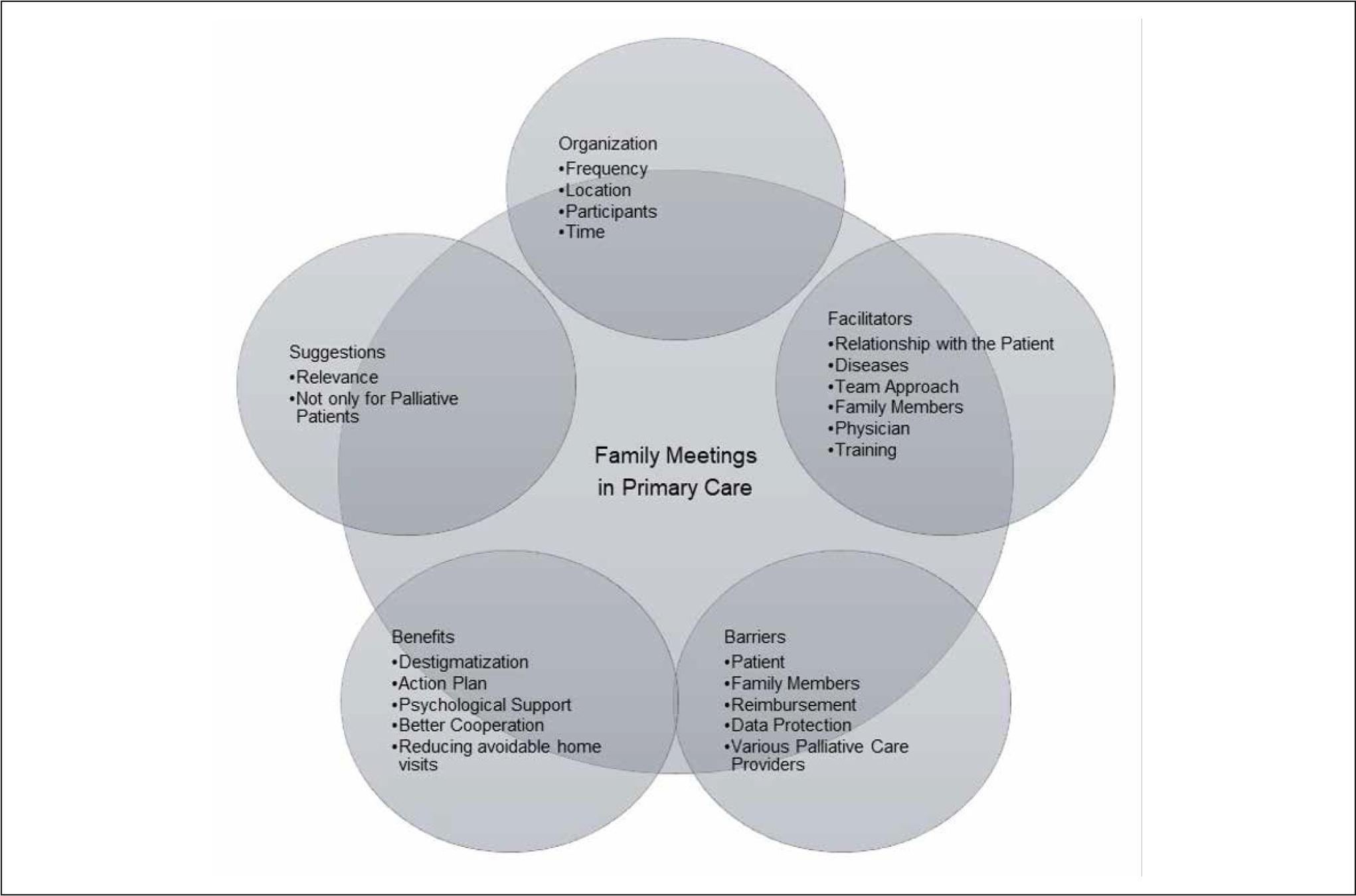

We identified the following themes: Organisation, Facilitators, Barriers, Benefits and Suggestions (Figure 1).

Overview of the main themes and their corresponding categories.

The theme organisation included 4 categories (Frequency, Location, Participants, Time) and 66 codes. Our research revealed that primary care FPs rarely conducted formal family meetings involving the patient, family members and interdisciplinary team. However, they often held meetings in a narrower setting. Such discussions were either spontaneous or planned. “It’s better to organise them because during home visits, you usually deal with some acute issues. Of course, it’s never wrong to use this time/opportunity if there’s no other way. However, it’s better to prepare for it, ask yourself a few questions, what concerns you about the patient, do you know the family dynamics, whom you’ll ask what…” (FP 3)

There were two types of meetings based on whether a conclusion or advanced care plan was accepted. A meeting with an open ending was well described by the following statement: “It’s a first step to talk about death. That it’s something that will happen in the future, but we don’t know when, and to open up these topics. Often people are shocked at the beginning because they’re not used to talking about death and these things. And within a year, we come to some consensus through several discussions.” (FP 10)

FPs led and organised family meetings differently according to their work style and beliefs. Meetings also varied due to different situations and relationships. “It’s like solving equations. I have a model, I know what I need to cover, and I do cover it, but I must catch the thread where they lead me, with their understanding of the diseases.” (FP 7)

In this theme we included 6 categories (Relationship with the Patient, Diseases, Team Approach, Family Members, Physician, Training) and 59 codes. FPs found it easier to conduct family meetings when there was trust, which was fostered by a strong patient-physician relationship, patient trust in the institution, and mutual trust among staff.

A common reason for meetings is the need to exchange information. “… my need for broader insight, meaning how family members experience specific situations. Family meetings are particularly helpful for me in further decision-making and of course for family members who may not understand the situation well …” (FP 13)

Another incentive for a meeting was the perceived discord among stakeholders (healthcare team, patient and relatives), such as pressures for futile treatment due to unrealistic expectations. “I had a case where the husband didn’t want to accept that his wife would die./…/But the lady accepted her condition. She was okay being at home, resting. The husband insisted on everything, and then we had to stop him.” (FP 9)

On the physicians’ side, motivating factors included interest in palliative care, a sense of competence, training, and professional and personal experiences with the dying person.

FPs conducting family meetings with a broader team recognised the presence of colleagues as highly beneficial, as tasks were distributed and the burden was shared.

This theme included 5 categories (Patient, Family members, Reimbursement, Data Protection and Various Palliative Care Providers) and 37 codes. The most significant barrier to conducting family meetings at the primary level was a lack of time. “You really have to take at least an hour to do this. Most of them, I did them all at the patient’s home, so you must drive to them. That’s difficult during working hours… and then you go for a home visit after work.” (FP 9)

There was also difficulty in coordinating staff time due to different work schedules for physicians, district nurses and colleagues, and there were no established pathways for collaboration with non-healthcare workers. Coordination in nursing homes was somewhat easier since teams were already formed, but physicians are not part of these teams. “We must acknowledge that physicians come from different institutions. On paper, we’re not considered the same team, but in practice, we must act as if we are. Sometimes coordination works seamlessly, and everything can be arranged, but sometimes it doesn’t.” (FP 6)

The challenge of organising meetings and the additional time required often led FPs to conduct meetings with a narrower circle, sometimes alone with the patient and/or relatives, and to communicate the decisions to the team later.

Another barrier for conducting family meetings was that they were not recognised as a professional service by insurance companies and were not paid for. “I would spend half a day just for a family meeting. If this were recognised as a service that I could bill, more physicians would opt for it. But that’s not the case.” (FP 6)

It also happened that the patient or relatives declined a family meeting, and physicians respected their decision, honouring the patient’s autonomy and privacy.

Five categories (Destigmatisation, Action Plan, Psychological Support, Better Cooperation, Reducing Avoidable Home Visits) and 54 codes ware included in this theme. FPs noticed significant benefits of family meetings. Patients experienced less suffering and found it easier to accept their diseases, while employees experienced less stress and made easier decisions. “… there were incredibly positive results in terms of better care, more accurate monitoring of disturbing symptoms by healthcare staff, appropriate response to disturbing symptoms, observation of the effect of medications and measures. Consequently, there’s significantly less stress experienced by employees, both due to patients and communication with relatives.” (FP 1)

Family meetings were an effective tool for bilateral information delivery and provided a safe space where patients and families could express their emotions and feelings and receive psychological support. “It’s essential to uncover those questions that are important to the patient, not just to me, and to establish trust so that later, if they need anything, they can easily call.” (FP 8)

The family meeting facilitated the establishment of collaboration between the physician and relatives and laid the foundation for an action plan, which is crucial for reducing distress during exacerbations and reducing the unnecessary burden on the system in the future. “The time spent in the family meeting: I get it back, and so does the system because patients somehow feel that the paths they’re turning to are clear, and they know they’ll get what they wanted, and they’re willing to wait a little. These patients with whom you reach a good agreement, practically never call the emergency service because there’s no need for other treatments at the secondary level.” (FP 4)

Finally, FPs also observed a broader effect of such conversations in society: “After all, they also contribute to destigmatising dying, death, finality, which is good for both relatives and patients and also for the entire healthcare staff dealing with it.” (FP 6)

This topic included 2 categories (Relevance, Not Only for Palliative Patients) and 24 codes. Palliative care was tailored to the patient, their relatives and their situation, and the approach was highly individual. “Surely, we have relatives and patients who need it more, even express a desire for it. Perhaps we’re a bit neglectful here too because we don’t actively offer it to those who don’t express the need for it unless we detect any issues. But that doesn’t mean there are no problems.” (FP 6)

Good practice to avoid unresolved distress was for the physician to implement an open-door policy. However, physicians saw the relevance of family meetings at every major milestone from diagnosing a chronic incurable disease onwards. Especially with the expected decline in cognitive functions, it was advisable to have a family meeting early, while the patient could still express their will.

The study’s findings offer valuable insights into the perceptions and practices of family physicians (FPs) regarding family meetings in palliative care settings. One of the most important findings is the recognition of family meetings as an essential tool for fostering communication, supporting shared decision-making and alleviating caregiver burden. This aligns with previous research that emphasises the benefits of family meetings in primary care settings (19). However, the study also identifies key barriers that hinder the successful implementation of family meetings. Time constraints remain the most frequently cited challenge in our study, with many FPs reporting difficulty in organising these meetings due to competing demands in their practice. Furthermore, a lack of formal preparation for family meetings, such as advance discussions about the meeting’s goals, involvement of key individuals and a clear care plan, is a significant issue (15, 17). This lack of structure contrasts with guidelines for family meetings in palliative care, highlighting a need for better organisational frameworks and preparation strategies (17). Maintaining continuous care is a vital ethical principle in palliative care, even as patients transition between different levels of care or receive concurrent management from both the FP and the mobile palliative care team (15, 36). However, in Slovenia, tasks are not yet clearly defined, and communication often takes place through reports or family members. A Slovenian study, conducted in a hospital setting, found that despite recognised benefits, family meetings are not always conducted (16). The barriers to conducting family meetings are similar to those encountered in delivering palliative care in primary care, with family physicians identifying a lack of time as the primary obstacle (37). Glajchen and colleagues identify challenges in scheduling meetings and coordinating the interdisciplinary team’s collaboration in oncology (7). Another barrier is unpreparedness for conversation among patients and their families (7, 18, 19). Oncologists cite also lack of training as a barrier to communication with patients and caregivers (7). In contrast, family physicians assess themselves as having sufficient competence for such discussions (19). Although additional training and a sense of competence are seen as facilitating factors, a lack of experience is not considered a barrier; it is replaced by better preparation for the meeting. This might be due to different roles in care: oncologists concentrate on achieving a cure, whereas family physicians accompany patients from their initial concerns to the end of life (19) and engage in challenging conversations daily. The presence of other team members was recognised as a supportive factor for conducting family meetings (16). Multidisciplinary composition during family meetings leads to more effective discussions and is recommended, but needs more preparation (3, 15, 16, 20, 38). At the primary level, options are limited, and some do not perceive the need for a wider circle of attendees; some include other professionals later as needed or have a separate team meeting with them, while many cite a lack of time as a reason for not organising the meetings (37). This was also noted in hospice care, where they considered the need to respect time constraints, and suggested that a simpler intervention model would be easier to implement in practice (20). Additional research is needed to measure the cost-effectiveness of family meetings (7). Based on the results of our study, it could be argued that family meetings should be recognised as a professional service paid for by the Health Insurance Institute of Slovenia, and consideration should be given to establishing efficient pathways for easier collaboration of different, even non-medical, professionals with general practices. Multidisciplinary collaboration or networking and financial arrangements would not only encourage the conducting of family meetings but also the provision of comprehensive palliative care in primary care (3, 37). Consistent with previous research, FPs recognise family meetings as an effective tool for exchanging information, supporting joint decision-making and reducing caregivers’ burden (7, 18). Like their Australian colleagues, Slovenian FPs also assess the family meetings as economical despite the high time investment (19), since they could help prevent unnecessary strain on hospitals and emergency services (15). An open and honest conversation with appropriate planning minimises the need for complex family meetings (39). Nonetheless, maintaining regular contact is advisable even in stable conditions, with the interval depending on the expected survival, ranging from one month to one year (7, 39). FPs in our study point out a significant need for family meetings for all incurable patients, even if palliative care is not (yet) discussed. This actually confirms the finding of the European Forum for Primary Care that FPs are less likely to recognise impending death in patients with endstage organ failure and old age or dementia compared to cancer patients (37). The episodic nature of non-cancerous diseases can lead to delays in recognising the transition to palliative care, and it is encouraging that FPs at least recognises the need for conducting a family meeting (3, 37). This is particularly significant because the greater the number of FPs, the greater the likelihood of home-based end-of-life care for cancer patients, while an increase in non-physician healthcare workers raises the probability of home-based care for other patient groups (40). This indicates that FPs will have more frequent contact with both patients and their relatives and emphasises the importance of family meetings.

A significant limitation is that the sample only includes physicians who already conduct family meetings, potentially overlooking the perspectives of those who do not engage in such practices. This introduces a selection bias, as it may not fully capture the barriers faced by FPs who might not conduct family meetings despite recognising their importance. Furthermore, the study sample is predominantly female, reflecting the local demographic characteristics of family physicians involved in palliative care. Additionaly, participants were from six of Slovenia’s 12 regions, each with a different organisation of palliative care, which may limit the transferability of the findings to other contexts.

In qualitative research, the value lies in its ability to explore complex social phenomena rather than making generalisable conclusions. The strength of this study lies in its focus on understanding the nuanced experiences of family physicians and the challenges they face in providing palliative care. The study provides a detailed look at the barriers to conducting family meetings, offering insights into the need for better preparation, clearer roles and improved support systems. These findings underscore the importance of family meetings as a practice that can significantly enhance patient care, particularly in primary care settings.

In conclusion, this study highlights both the challenges and importance of implementing family meetings in primary care. While family physicians often engage in valuable but informal conversations with patients and their families, time constraints and lack of preparation hinder their formalisation as structured family meetings. The study suggests that simplifying these models, offering structured training for family physicians, fostering multidisciplinary collaboration and addressing financial disparities could enhance their integration into routine practice. Further research on the cost-effectiveness of family meetings could support necessary policy changes, ultimately improving care coordination and benefiting both patients and their families.