Online reviews popularity and their impact on individual buying behavior give rise to the argument that information provided on online platforms is more influential among consumers nowadays. In the hospitality industry, online reviews are widely accepted to play a significant role in influencing guests’ experiences and improving the service quality of the hotels (Hu et al., 2019). Hotel guests as well as hotels can benefit greatly from the use of online reviews. For hotel guests, other customers' opinions are a great help in making a purchase decision. In turn, for hotels online reviews are valuable and provide detailed insights into customer satisfaction and customer experience of the services provided. In a study by Medill Spiegel Research Center (SRC) about the power of online reviews in shaping customer behavior displaying reviews, soar conversion rates rapidly and when a product receives five reviews, the likelihood of purchase increases by 270% (cswenson, 2021). Hotel owners pay special attention to negative online reviews because they are perceived as more trustworthy, selfless, and impactful than positive ones (Cunningham et al., 2010). This study aims to identify the attributes which play a significant role in customers' purchase preferences. Attribute-based shopping is a purchase method that matches customers' desires with the purchase of a product/service. Looking at the most complaint attributes mentioned on online reviews by hotel guests could provide a greater understanding of the dynamics of poor reviews and their impact on customers' purchase decisions and satisfaction.

Hotel performance attributes encompass various features that customers consider essential when choosing a hotel or assessing the quality of its services and facilities. The concept of ‘importance’ and ‘unimportance’ in this context has been previously established in the literature (Callan, 1997). In 1985, Parasuraman, Zeithaml, and Berry—three American marketing scholars—identified ten service quality dimensions based on customer evaluations: Reliability, Tangibles, Responsiveness, Competence, Access, Courtesy, Communication, Credibility, Security, and Understanding. Later, in 1988, they refined these ten dimensions into five, introducing the SERVQUAL Model, which consists of five key service dimensions: Reliability, Assurance, Tangibles, Empathy, and Responsiveness (Kobiruzzaman, 2020).

The 5 dimensions of service attributes encompass (Parasuraman et al., 1985):

Reliability: Ensuring services are delivered accurately, punctually, and credibly, emphasizing consistency, like timely mail delivery to customers.

Assurance: Building trust and credibility through factors like competence, courtesy, credibility, and security, exemplified by showing respect and politeness during customer interactions.

Tangibles: Focusing on the physical aspects such as facilities, employee appearance, equipment, and information systems, including elements like organizational cleanliness and staff attire.

Empathy: Concentrating on attentive customer service to provide caring and personalized experiences, incorporating factors like accessibility, effective communication, and understanding customer needs.

Responsiveness: Demonstrating eagerness to assist customers promptly and respectfully, emphasizing willingness and quick service delivery, ensuring customers feel valued and their issues are addressed promptly.

In the SERVQUAL model, Parasuraman et al. (1988) identify tangibility as a key dimension in assessing service quality. According to Albayrak, Caber, and Aksoy (2010), tangible attributes have a stronger impact on overall guest satisfaction because they can be easily modified or upgraded. Similarly, Oberoi and Hales (1990) emphasize the significance of tangibility in the hotel industry, while Joes and Lockwood (2004) suggest that hotels should prioritize tangible aspects in their operations to enhance customer satisfaction. Most hotel products consist of both tangible and intangible attributes, which are closely interconnected and play a crucial role in shaping guests' perceptions of quality (Alzaid & Soliman, 2002). The concept of ‘tangibility’ or ‘physical quality’ typically refers to various service elements, including the appearance of facilities, equipment, staff presentation, advertising materials, and other physical features involved in service delivery. Within the hotel industry, tangibility encompasses the external appearance of hotel buildings, accommodation, and restaurant facilities. Unlike intangible aspects, tangible elements can be objectively measured, evaluated, and standardized (Marić D. et al. 2016). Johnston (1995) categorizes tangibility into two aspects: the cleanliness and neatness of physical components and the comfort of the service environment.

Numerous studies have examined the perceptions and preferences of both hotel managers and customers in the hospitality industry. Research on managers' perspectives in UK hotels (Callan, 1997) involved assessing their views on how customers perceive the importance of various attributes when selecting a hotel and evaluating service quality. The findings suggest that while some leisure and security attributes are considered relatively unimportant, service provider-related attributes hold greater significance. Similarly, a study on UK hotel customers' perspectives (Callan, 1998) revealed that leisure, entertainment, and child-related services are not viewed as essential, reinforcing the emphasis on service-related attributes over leisure and security factors for both managers and customers.

Yang et al. (2003) explored the impact of unique service quality dimensions in internet retailing on consumer satisfaction. Their findings identified responsiveness, credibility, ease of use, reliability, and convenience as the most frequently cited service attributes contributing to customer satisfaction.

To optimize pricing strategies, hotel managers must understand the marginal utility customers associate with specific hotel attributes. Masiero et al. (2015) conducted a study using a stated choice experiment and discrete choice modeling to determine hotel guests' willingness to pay (WTP) for specific room attributes within a single hotel property. These attributes included room views, hotel floor, club access, complimentary mini-bar items, smartphone service, and cancellation policies. The study found that WTP values varied between leisure and business travelers, as well as between first-time and repeat visitors. These insights assist hotel managers in market segmentation and revenue management strategies to maximize profitability (Masiero et al., 2015).

As summary the SERVQUAL model, developed by Parasuraman, Zeithaml, and Berry (1988), remains one of the most influential frameworks in assessing service quality. Although foundational, its core principles continue to inform contemporary service quality research. According to the model, service quality is assessed by comparing customer expectations with their perceptions of actual service performance. These expectations are shaped by word-of-mouth communication, personal needs, and past experiences, while perceptions are influenced by tangible service characteristics such as responsiveness, assurance, empathy, reliability, and tangibles. This gap between expectations and perceptions—if negative—leads to perceived service quality deficits, which in turn contribute to customer dissatisfaction. When dissatisfaction occurs, it may manifest as negative word-of-mouth, online complaints, or switching behavior.

The growth of online consumer reviews has been widely recognized over the past decade. To explore the motivations behind consumers expressing their opinions on web-based review platforms and social media, Hennig-Thurau et al. (2004) identified four key factors driving electronic word-of-mouth (e-WOM) behavior: the desire for social interaction, economic incentives, concern for other consumers, and the opportunity to enhance self-worth. Additionally, consumers engaging in e-WOM can be categorized based on the underlying motivations influencing their behavior (Hennig-Thurau et al., 2004).

To examine the impact of online reviews on consumer attitudes and behaviors, Browning et al. (2013) studied how online hotel reviews shape consumer perceptions of service quality and the extent to which businesses can manage service delivery. Their findings indicate that reviews focusing on core services are more likely to generate positive service quality perceptions, whereas negative reviews adversely affect consumers' opinions. The study emphasizes the importance of maintaining core service quality and the need for hotel managers to address customer service issues promptly (Browning et al., 2013).

Philips et al. (2017) proposed a model explaining which aspects of visitor experiences, as shared on social media, have the greatest influence on hotel demand. Their research highlights that hotel attributes such as room quality, internet availability, and building conditions significantly impact hotel performance, with positive reviews having the strongest effect on customer demand (Phillips et al., 2017).Together, these insights underscore the importance for firms to tailor strategies for encouraging e-WOM behaviour and to prioritize the management of core services and positive customer experiences to optimize performance in the digital era.

Customer complaint behavior is generally understood as a range of responses triggered by dissatisfaction with a purchase (Yuksel et al., 2006). In recent years, researchers have increasingly focused on the factors influencing consumer complaint intentions and behaviors. Crié (2003) classified consumer responses to dissatisfaction into two main categories: responses directed at an entity—public responses, such as complaints to the company, versus private responses, such as word of mouth—and behavioral versus non-behavioral actions, including legal action, doing nothing, or choosing to forget and forgive (Crié, 2003).

Gyung Kim et al. (2020) introduced a conceptual model outlining four coping strategies for managing stress caused by dissatisfaction: taking no action (inertia), engaging in negative word of mouth (negative WOM) against the service provider, directly complaining to the provider, or lodging a complaint with a third party (Gyung Kim et al., 2020). Research indicates that 32% of surveyed consumers would stop purchasing from a brand after a negative experience, even if they were previously loyal to it (Runge, 2024). The consequences of service failures become more severe when dissatisfied customers share their experiences on social media and online review platforms.

Sundaram et al. (1998) identified four key motives behind negative WOM: altruism (warning others to prevent similar issues), anxiety reduction, seeking vengeance, and requesting advice (Sundaram et al., 1998). To understand variations in online complaint behavior across different hotel categories, Sann et al. (2022) examined how guests at hotels with different star ratings express dissatisfaction. Their findings indicate that guests at higher-star-rating hotels are most likely to complain about service encounters in large hotels; value for money and service encounters in medium-sized hotels; and room space along with service encounters in small hotels (Sann et al., 2022).As a summery, hotel performance attributes play a crucial role in shaping guest experiences and determining overall satisfaction. These attributes, ranging from service quality and responsiveness to physical amenities, influence how customers perceive a hotel's value. The SERVQUAL model categorizes these attributes into five key dimensions: reliability, assurance, tangibles, empathy, and responsiveness. Among these, tangibles— including hotel facilities, cleanliness, and room conditions—have been identified as the most frequently criticized factors in negative online reviews. As online reviews continue to shape consumer decisions, understanding the aspects that lead to customer dissatisfaction is essential for hotel managers. Prior research highlights those different types of travellers value hotel attributes differently, with factors such as room views, location, and additional amenities affecting their willingness to pay. By analysing consumer complaints and their underlying motivations, hotels can better align their offerings with guest expectations, improve service delivery, and enhance customer loyalty.

This study adopts an exploratory and inductive approach, utilizing content analysis of secondary data as its primary methodology. The data for this research is sourced from publicly available secondary data on Booking.com, covering the period from August 4, 2015, to August 3, 2017 (Kaggle.com). While the original dataset includes 515,000 customer reviews and ratings of 1,493 luxury hotels across Europe, this study focuses specifically on hotels in Italy.

From the dataset, 142 Italian hotels were identified; however, only 35 hotels with the highest number of negative reviews—ranging from 5,000 to 55,000 reviews—were selected for analysis. All selected hotels are chain-operated city center hotels. To evaluate the dimension of service attributes, SERVQUAL model has been used in this research. Accordingly, Reliability includes “Provide service on time and Without error”. Assurance as trust and credibility, include “Competence, Courtesy, Credibility, and Security”. Tangibles include “Physical facilities, the Appearance of the employees, Equipment, Machines, Cleanliness”. Empathy is an essential attitude to serve every customer individually and to increase their trust and loyalty. Empathy includes “Access (physical and social), Communication, Understanding the customer”. Finally, Responsiveness is defined by the length of time when customers wait for the answer or solution and include “Willingness and Promptness”.

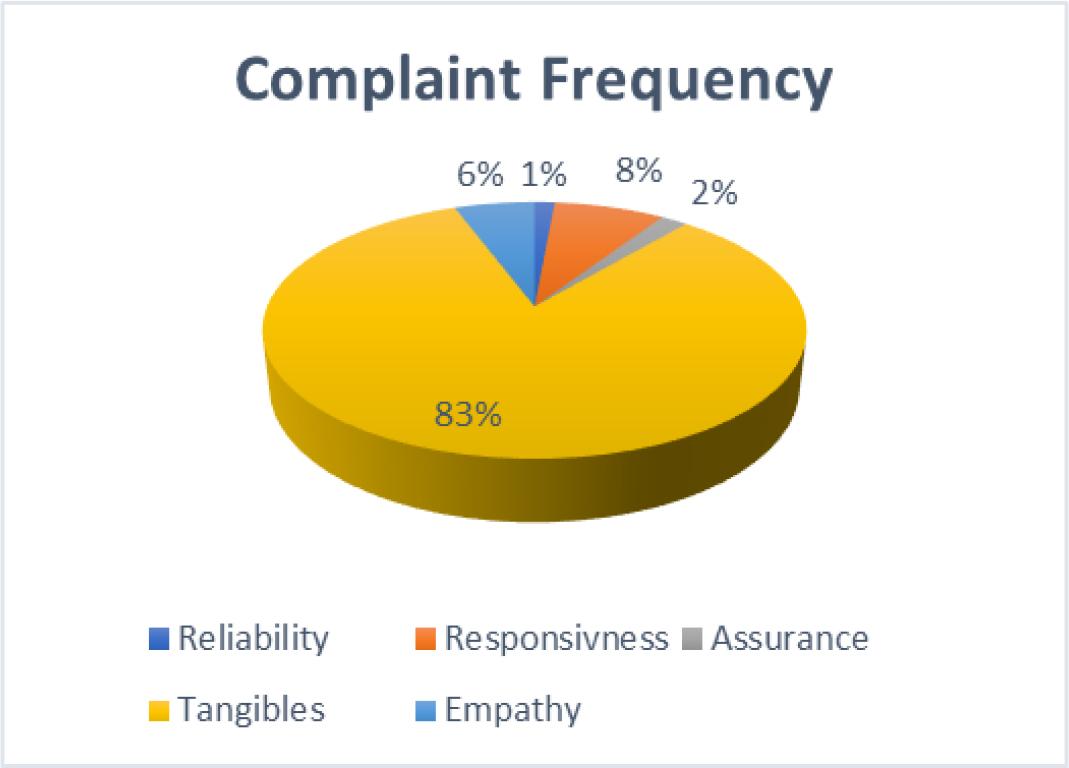

Graph. 1 shows the frequency of complaints in service attributes according to SERVQUAL model in the database of hotels from Italy. From a total number of 37207 cases (negative online reviews), “Tangibles” has been mentioned in 83% of the cases and is the most critical service attribute that hotel customers complain about. Next, “Responsiveness” with 8%, “Empathy” with 6%, Assurance with 2% and finally “Reliability” with 1% represent the other service attributes which have been measured in the database.

Complain Frequency in service attributes.

Source: Created by the author

Since the aim of this study is to investigate what hotel customers complain about mostly and to understand which hotel attributes are important for consumers, a qualitative data analysis software, QDA Miner, has been used to do a comprehensive content analysis on the negative online reviews. Table 1 shows examples of negative online reviews according to the most criticized scale namely “Tangibles of Service” with the frequency of the cases (online reviews) per each category.

Tangibles of Service A (General categories)

| Tangibles A -Categories and Frequencies of the cases (online reviews) | Examples |

|---|---|

| Hotel Physical Facilities (525) | -Hotel under staff Hotel and all FACILITIES are very old |

| Appearance of the employees (0) | |

| Equipment (64) | -Lack of plugs to recharge phones and other electronic EQUIPMENT |

| Machines (25) | -coffee MACHINES were out of order |

| Cleanliness (70) | -CLEANLINESS Bad smell in room |

| Location (1267) | -LOCATION is out of town in an ex industrial district |

| Design-Décor (3496) | See table 2 |

| Room (30988) | See table 3 |

Source: Created by the author.

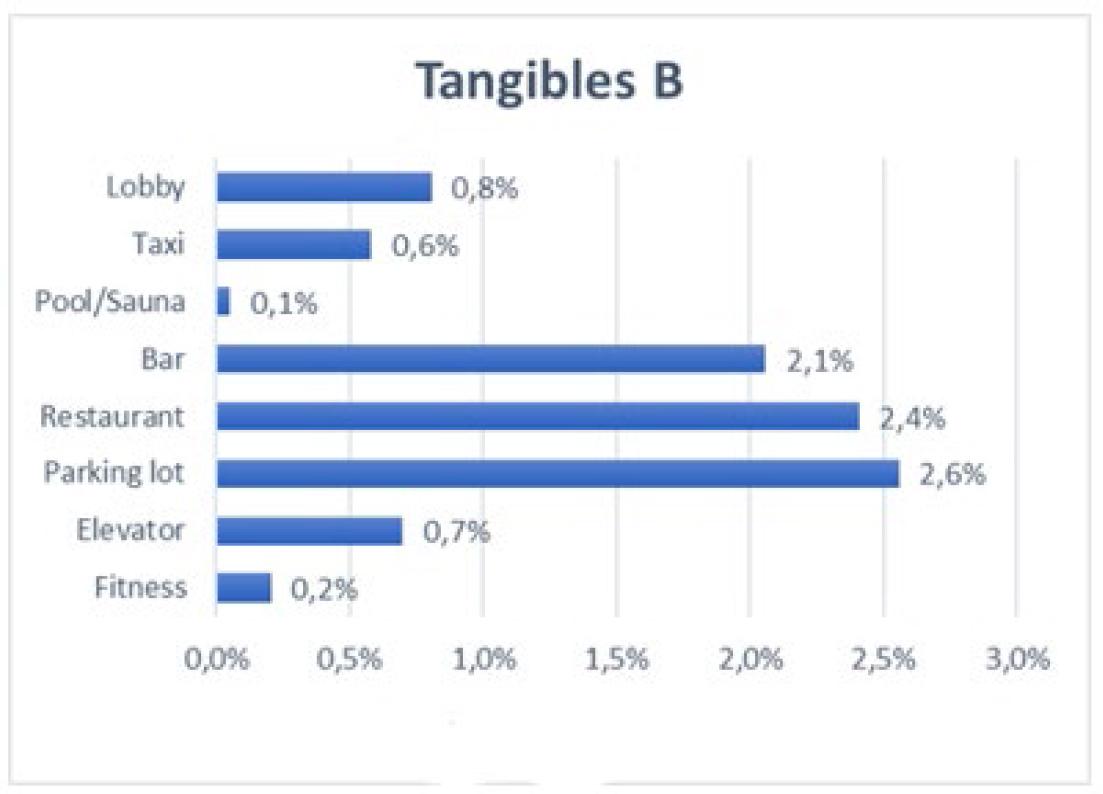

Table 2 shows examples of negative online reviews according to the most criticized scale namely “Tangibles of Service” with the frequency of the cases (online reviews) per each category of “Design-Décor”.

Tangibles of Service B (sub-categories of Design-Décor)

| Tangibles B-Sub-Categories of Design-Décor and Frequencies of the cases (online reviews) | Examples |

|---|---|

| Fitness (78) | -The FITNESS center is quite small and has only one equipment for all muscles with missing handles |

| Elevator (261) | -The ELEVATOR is super small We could barely fit two people with our bags in it. |

| Parking lot (953) | -PARKING is quite expensive. |

| Restaurant (897) | -The small RESTAURANT in the hotel has a limited variety of foods and the prices are quite expensive |

| Bar (767) | -Rooftop bar was not open during my stay. |

| Pool/Sauna (21) | -paying extra for SAUNA POOL facility |

| Taxi (217) | -on front desc call a TAXI for us to airport and the guy say it will cost you 70 euro but TAXI driver says 95 and we argue little. |

| Lobby (302) | -Small LOBBY not much going around. |

Source: Created by the author.

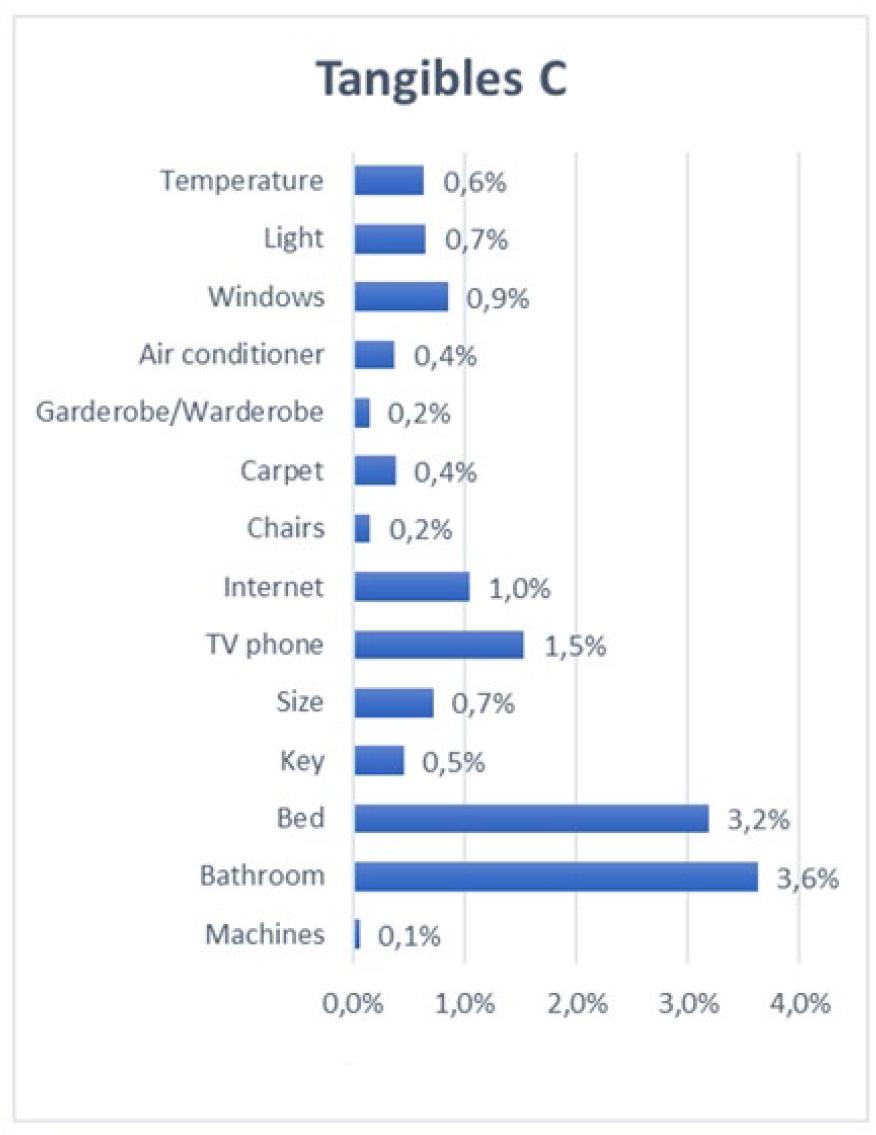

Table 3 shows examples of negative online reviews according to the most criticized scale namely “Tangibles of Service” with the frequency of the cases (online reviews) per each category of “Room”.

Tangibles of Service C (sub-categories of Room)

| Tangibles C-Sub-Categories of Room and Frequencies of the cases (online reviews) | Examples |

|---|---|

| Hotel has no room SERVICE at night |

| -There was an issue with hot water in the BATHROOM |

| -The BED is too old. |

| -Room KEY card found to open several other rooms suggesting major security issues. |

| -The SIZE of the shower is quite narrow, and I found my elbows kept hitting the walls. |

| -No TV channels in English |

| -INTERNET was very slow |

| -The CHAIRS in tv room were uncomfortable |

| -The carpet in the room was a bit grotty. |

| -very small WARDROBE space to put your clothes |

| -Air CONDITIONER in the room was not operative. |

| -Room small and with little WINDOWS |

| -The LIGHT in the room is very dusky |

Source: Created by the author.

Graph. 2 shows the frequency of complaints in service attribute “Tangibles of Service” focusing on sub-categories of “Design-Décor”. Ranking the data in order from high to low, Parking lot, Restaurant, Bar, Lobby, Elevator, Taxi, Fitness, and finally Pool/Sauna have been mentioned as complained attributes related to “Design-Décor” category.

Frequency of complaints related to Tangibles of Service B (sub-categories of Design-Décor)

Source: Created by the author.

Graph. 3 shows the frequency of complaints in service attribute “Tangibles of Service” focusing on sub-categories of “Room”.

Frequency of complaints related to Tangibles of Service C (sub-categories of Room)

Source: Created by the author.

Ranking the data in order from high to low, Bathroom, Bed, TV/Phone, Internet, Windows, Light and Size of the room, Temperature, Key, Air conditioner and Carpet, Garderobe/Wardrobe and Chairs, and finally Machines have been mentioned as complained attributes related to “Room” category.

This study used an inductive approach and the SERVQUAL model to evaluate negative customer reviews of 35 Italian hotels, highlighting the tangible aspects of service quality as the primary source of dissatisfaction. Among the 37,207 negative online reviews analyzed, 83% of complaints were related to tangibles, followed by responsiveness (8%), empathy (6%), assurance (2%), and reliability (1%). These findings reinforce previous studies (e.g., Albayrak et al., 2010; Oberoi & Hales, 1990) that emphasize the significant role of tangible elements—such as cleanliness, room conditions, equipment, and physical facilities—in shaping customer satisfaction in the hospitality sector.

The high frequency of complaints related to tangibles is consistent with the findings of Marić et al. (2016), who identified measurable and visible features of service environments as strong predictors of customer dissatisfaction when subpar. Furthermore, this study aligns with the work of Hu et al. (2019), who used topic modeling to reveal that hotel guests frequently express dissatisfaction with outdated facilities and poor maintenance in online reviews.

A deeper content analysis showed that within tangibles, room attributes such as bathroom conditions, bed quality, and room size were most frequently criticized, corroborating Masiero et al.’s (2015) findings that guests' willingness to pay is highly sensitive to in-room features. Similarly, location and noise levels, which emerged as additional pain points, are known contributors to negative word-of-mouth in the hospitality industry (Browning et al., 2013).

This study also supports the theoretical foundation of the SERVQUAL model: when service perceptions fall short of expectations, especially in tangible dimensions, customer dissatisfaction increases, often leading to public complaint behaviors via online platforms. These behaviors are not only emotional responses, but also strategic actions aimed at warning other consumers, as shown in the work of Sundaram et al. (1998).

In sum, the findings confirm the centrality of tangible service components in driving dissatisfaction and digital complaint behavior in hotel guests. Moreover, the integration of content analysis with SERVQUAL contributes methodologically by demonstrating how structured service models can be used in qualitative review mining

Overall, the study aims to understand consumers' primary complaints and the importance of various hotel attributes, providing valuable insights for hotel management to address service deficiencies and enhance customer satisfaction. Hotels cannot control online ratings and negative reviews, but they can evaluate and analyse them. This can provide insights that make it possible to provide better service quality, develop better offers, increase willingness to pay, and decrease gusts dissatisfaction (Fedewa, 2021).

This study investigated the dimensions of service quality that trigger customer dissatisfaction by analyzing negative online reviews of Italian hotels. By applying the SERVQUAL model, it was found that tangible service attributes overwhelmingly account for customer complaints, confirming the importance of physical and visible service features in the hospitality context.

The main contribution of this study lies in its empirical confirmation of SERVQUAL's applicability to large-scale, real-world review data. The work bridges the gap between theoretical service quality models and digital consumer feedback, demonstrating how user-generated content can be systematically categorized using established frameworks. Furthermore, the study offers practical implications for hotel managers, emphasizing the urgent need to address tangible service failures such as poor room conditions, equipment malfunction, and substandard cleanliness—factors most closely tied to customer dissatisfaction and subsequent online complaints.

From a theoretical standpoint, the study advances the understanding of complaint behavior as a function of expectation-perception gaps, aligning with prior literature but adding depth through a rich dataset of unfiltered customer voices. It also reaffirms the value of e-WOM as a powerful consequence of unmet service expectations.

While this study provides valuable insights, several areas warrant further investigation:

Cross-cultural comparisons: How do customer expectations and perceptions differ across cultures when evaluating service quality in hospitality?

Temporal changes: Do complaint patterns shift over time in response to changing guest expectations, especially in the post-COVID travel era?

Integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning: Can AI, automated sentiment and topic modeling be combined with SERVQUAL for real-time service monitoring?

The impact of managerial responses: How does the responsiveness of hotel management to online reviews influence future guest behavior?

Future studies could also expand beyond the SERVQUAL framework, incorporating emotional and experiential factors that are increasingly important in hospitality marketing.

Although many hotel companies have begun to analyze customers' complaint behavior, the industry has yet to fully explore the potential of this emerging data resource. One of the generally accepted marketing principles is that retaining existing customers and improving their re-purchases is more profitable than attracting prospective customers (Noone et al., 2011).

Gartner’s research found that the role of customer service in increasing customer loyalty is critical, as 97% of customers are more likely to spread their positive opinion if they receive value during a service interaction (Gartner, 2024). To improve guests’ satisfaction and prevent the potential risk of customers’ negative online reviews, hospitality managers should closely monitor online complaints and understand why customers are dissatisfied with hotel services.