We confirm across multiple large cohorts that MSU crystals alone have limited effects on IL-1β production and that they synergize with palmitate to increase IL-1β production.

MSU crystals alone do not induce significant transcriptomic changes in PBMCs after 24 hours of exposure.

The addition of MSU to palmitate or LPS does not result in additional significant transcriptomic alterations.

These results support the model that MSU crystals alone are insufficient to trigger strong inflammatory responses without an additional stimulus that promotes pro-IL-1β expression.

Monosodium urate (MSU) crystals are the insoluble form of urate, consisting of urate molecules bound to a sodium and a water molecule, which aggregate to form needle-shaped crystals. These crystals typically accumulate in joints, where they cause an inflammatory response that clinically manifest as gout flares.[1] Gout flares commonly occur at night with intense pain, redness and swelling especially engaging the first metatarsophalangeal joint. Microscopic examination of affected joints during a flare shows a strong infiltration of neutrophils, along with monocytes and lymphocytes.[2]

Urate is the final product of purine catabolism in humans. Hyperuricemia, the condition in which the serum urate concentration is abnormally elevated, is usually achieved through a combination of increased purine dietary intake and decreased excretion of urate and is associated with obesity, dyslipidemia, type 2 diabetes or chronic kidney disease.[3] While hyperuricemia is required to develop gout, less than 20% of hyperuricemic individuals will develop a flare throughout their life.[4] Furthermore, deposition of MSU crystals in joints can be observed even in cases of asymptomatic hyperuricemia,[5,6] raising important questions regarding the conditions or additional triggers required to initiate a flare.

The interaction between MSU crystals and immune cells is complex, inducing a broad range of responses depending on the cell type, crystal size and even preparation method.[7,8] The initial immune response is triggered by synovial phagocytes, which generally consist of two main populations – local resident macrophages formed during embryonic development and circulating monocytes recruited from blood. Both macrophages and monocytes internalize MSU crystals and produce proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF,[9] that initiate the inflammatory response by recruiting additional immune cells. Interestingly, fibroblast-like synoviocytes have also been shown to phagocytose MSU crystals and produce IL-1β, although in significantly lower quantity.[10]

IL-1β is the key cytokine that mediates innate inflammatory response in gout. Its production is controlled in a two-step manner – first, transcriptional and translational induction of pro-IL-1β followed by its proteolytic activation by caspase-1 via the NLRP3 inflammasome.[11,12] To date, reports on MSU crystal-induced IL-1β production have shown mixed results. Some studies have found that sterile MSU crystals fail to induce a significant IL-1β production upon stimulation [13,14] and do not cause inflammatory arthritis when injected into mouse knee arthritis models[13,14] other reports demonstrate the opposite[15,16,17]. To contribute to this ongoing discussion, we aim to investigate the MSU-induced IL-1β production and describe the transcriptomic changes associated with MSU - triggered responses in primary human Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs).

The subjects were recruited at the Rheumatology Department of the “Iuliu Haţieganu” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Cluj-Napoca, Romania as part of the HINT Project (Hyperuricemia-induced Inflammation: Targeting the central role of uric acid in rheumatic and cardiovascular diseases). The diagnosis of gout was established by the ACR/EULAR 2015 classification criteria with a minimum score of 8. The detailed characteristics of the HINT study groups were previously described[18,19]. Validation was performed in separate cohorts recruited at Radboudumc, Nijmegen, The Netherlands as part of the Human Functional Genomics Project (https://www.humanfunctionalgenomics.org/): 200FG is a healthy control cohort[20] and 250Gout is a cohort of patients diagnosed with crystal-proven gout (crystals observed under polarized microscopy of synovial fluid aspirate or tissue puncture) by an experienced rheumatologist (TLJ). Informed written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Peripheral blood was drawn from the cubital vein into EDTA tubes under sterile conditions. PBMCs were separated using Ficoll-Paque density gradient centrifugation from the freshly drawn blood, washed 3 times with phosphate buffer saline solution and resuspended in RPMI culture medium RPMI (Roswell Park Memorial Institute) 1640, supplemented with 50 μg/ml gentamicin, 2 mM L-glutamine and 1 mM pyruvate. 0.5*106 cells were incubated for 24 hours with palmitate (50 μM) or LPS (10 ng/mL) with and without MSU crystals (300 μg/mL). Cells were incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2. The plates were centrifuged, and supernatants were separated for cytokine measurements. For RNA-seq experiments, after centrifugation and supernatant removal, the cells were stored in 50 μl TRIzol at −80°C.

MSU crystals were prepared as previously described[21] on the basis of the protocol described by Seegmiller et al.[22] In brief, 1 gram of uric acid was mixed in 200 ml of sterile water containing 24 grams of NaOH. The pH was adjusted to 7.2 after the addition of HCl followed by heating for 6 hours at 120°C. The solution was left to cool at room temperature and stored at 4°C. The crystals were confirmed to be 5–25 μm in length. LPS contamination was controlled by LAL-assay.

Regular experiments to check for potential LPS contamination were performed by MSU crystal stimulation of PBMCs in presence or absence of Polymyxin B (lack of effect of polymyxin B indicated LPS free stocks of highly pure MSU crystals).

Experiments were performed in duplicate and samples were frozen at −20°C before measured. The IL-1β concentration was measured by sandwich ELISA (R&D Systems kit) with a 78–5000 pg/ml detection range using BioTek Synergy HTX Multimode Microplate Reader. Total number of samples assessed are specified in the figure legends of the respective panels.

The two RNA-seq experiments and data analysis were performed independently. One experiment was performed in Cluj-Napoca, followed by bulk RNA-Sequencing analysis (commercial platform - DNBseq, Beijing Genomics Institute, Denmark). Quality control, mapping and quantification was performed following the nf-core pipeline. Raw reads trimming was performed with fastQC: reads with adaptors, low quality reads (unknown bases >10% or QC score < 15 in over 50% of the base pairs) and rRNA mapped reads were removed. All samples passed the quality control checks. Quantification was performed with Salmon.

A separate experiment was performed in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, followed by sequencing on the Illumina HiSeq 2500 system and the library was generated with TruSeq RNA sample preparation kits. Similar reads quality control was performed followed by alignment to GRCh37 using STAR and gene level quantification with HTSeq.

Normalization and differential expression analysis were performed with DESeq2 and, for pathway analysis, the clusterProfiler package was used. All genes with a padj<=0.05 and a Fold Change >2 or <−2 in at least 2 experiments were considered differentially expressed.

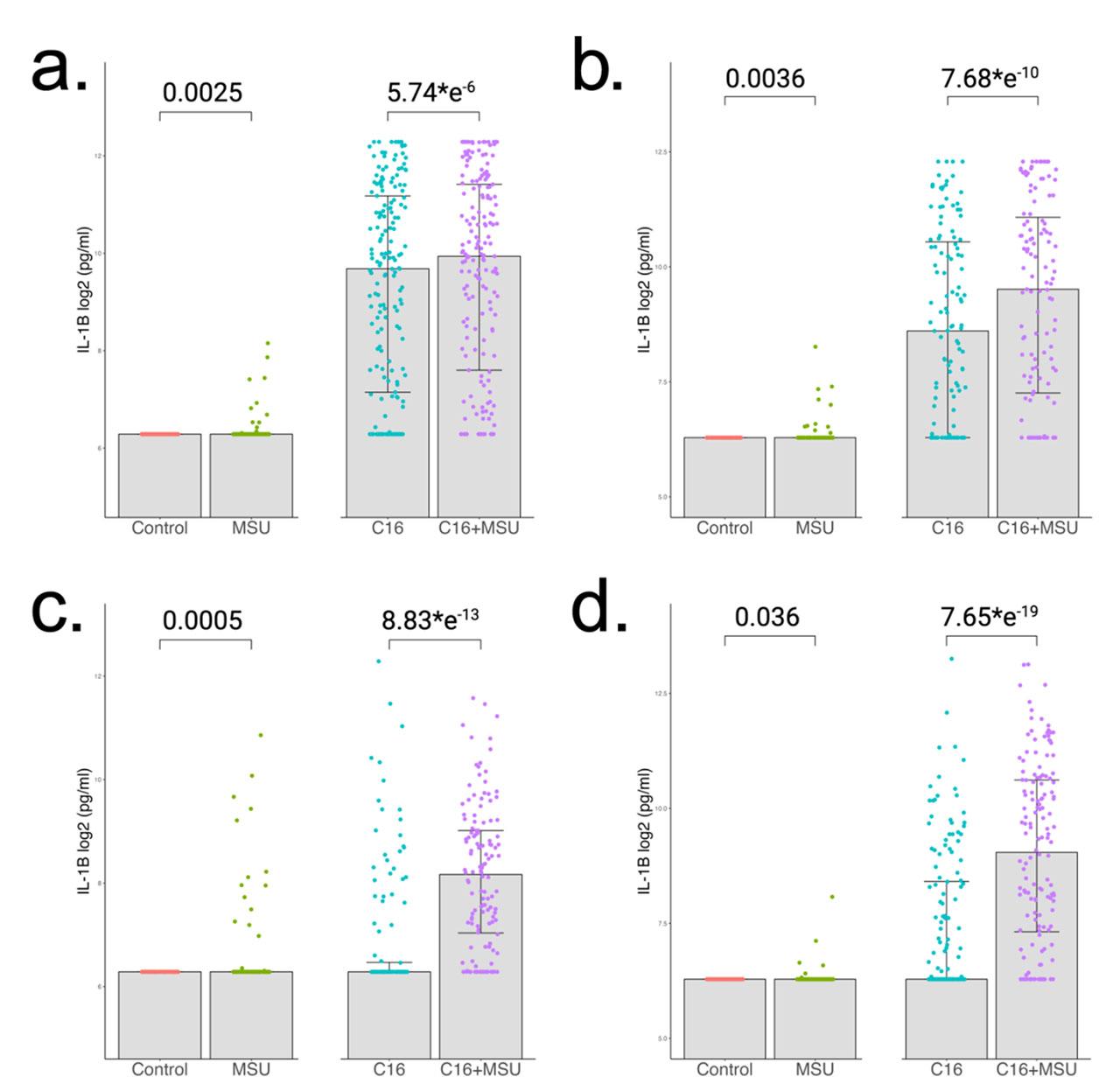

To assess the effect that MSU crystals have on IL-1β production, we performed an experiment in which freshly isolated human PBMCs were stimulated for 24 hours with MSU crystals (300 μg/mL), palmitate (50 μM), and a combination of MSU crystals and palmitate. The stimulation experiment was performed in multiple cohorts, and we investigated the HINT, 200FG and 250Gout cohorts. The HINT study groups included 181 normouricemic controls (Fig. 1a) and 123 gout patients (Fig. 1b). Additionally, the 200FG served as an additional control group with 132 controls (Fig. 1c), and 250Gout served as an additional gout group with a sample size of 148 (Fig. 1d). Depending on the statistical approach used, it can be concluded that MSU crystals alone induce limited increase in IL-1β when compared to control. A significantly stronger response is observed when comparing the palmitate-MSU combination with palmitate alone. P values range between 5.74*e−6 and 7.65*e−19 when the same statistical test is applied. All groups follow a similar pattern with larger effect sizes in gout.

IL-1β cytokine production in PBMCs after 24h stimulations. Cells were stimulated with MSU crystals (300 μg/mL), palmitate (50 μM) and the combination of both. Concentration of IL-1β were measured in supernatants by ELISA. The first cohort was split into (a) 181 normouricemic controls and (b) 123 gout patients. Similar analysis was performed in other cohorts which consist of (c) 132 healthy individuals and (d) 148 gout patients. Group differences were assessed by paired Wilcoxon test and the p values are reported.

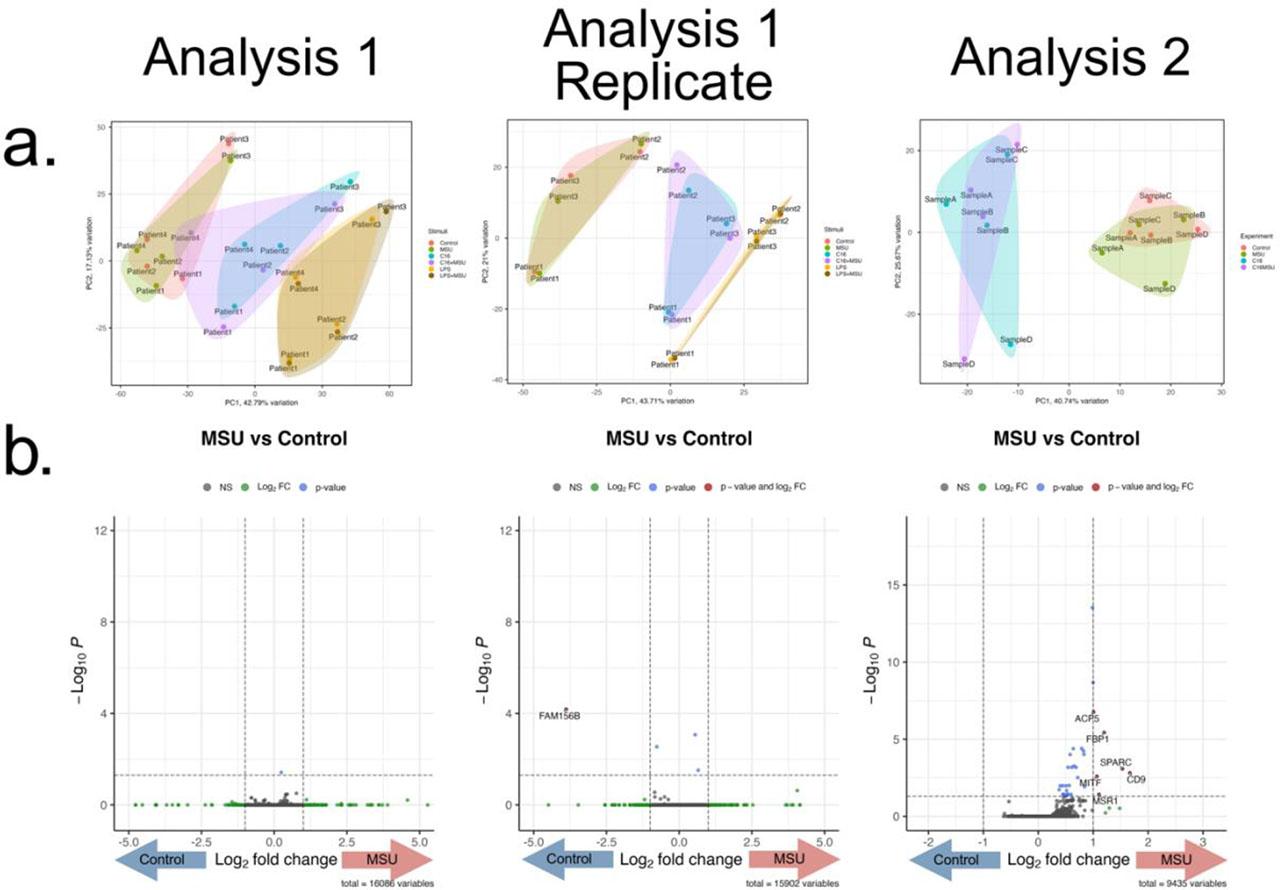

After confirming the upregulation of IL-1β cytokine production, we investigated the transcriptomic changes associated with it. Two experiments were performed independently. The first analysis consisted of PBMCs isolated from 4 gout patients that were stimulated for 24 hours with MSU, palmitate, palmitate+MSU, LPS, and LPS+MSU. In 3 patients the experiment was repeated, forming a replicate group. The second experiment included negative control, MSU, palmitate, and palmitate+MSU stimulations in 4 healthy donors. A general overview with a Principal Component Analysis biplot is presented (Fig. 2a), which depicts grouping of Control samples with MSU-crystals alone, palmitate with palmitate+MSU, and LPS with LPS+MSU stimulated samples, suggesting a similar transcriptomic signature in each pair. A differential expression analysis was performed comparing MSU to Control that shows no significantly differentially expressed genes (Fig. 2b).

RNA-seq after 24h PBMC stimulation with MSU crystals. (a) Principal Component Analysis Biplots of the 3 experiments. The first experiment contains 2 replicates (gout patients, n=4 and n=3), where cells were stimulated with MSU crystals (300 μg/mL), palmitate (50 μM), palmitate+MSU, LPS (10 ng/mL) or LPS+MSU. The second experiment (healthy individuals, n=4) was independently performed in the same experimental conditions with MSU, palmitate and palmitate+MSU stimulations. Clustering along the PC1 can be observed based on the experimental conditions (MSU with Control, C16 with C16+MSU, LPS with LPS+MSU) showing similar transcriptomic signatures associated with each pair. (b) Volcano plots depicting the results of the Differential Expression Analysis comparing cells stimulated with MSU crystals and control. X axis represents the log2 Fold Change and y axis the p value for each analyzed mRNA.

As previously shown, MSU crystals had a strong synergistic effect in combination with palmitate. We further explore the transcriptional changes associated with combinations of palmitate or LPS with MSU. Both palmitate and LPS were able to induce a strong response (Fig. 3a,c). The MSU crystals failed to produce any changes in both palmitate+MSU and LPS+MSU combination when compared to palmitate and LPS alone (Fig. 3b,d). Pathway analysis of palmitate + MSU crystals or LPS + MSU crystals revealed overlapping pathways compared to palmitate or LPS alone, respectively, such as TNF signaling, IL-17 signaling and NF-κB response (Fig. 3e).

RNA-seq after 24h PBMC stimulations with palmitate, LPS and MSU combinations. The first experiment contains 2 replicates (gout patients, n=4 and n=3), where cells were stimulated with MSU crystals (300 μg/mL), palmitate (50 μM), palmitate+MSU, LPS (10 ng/mL) or LPS+MSU. The second experiment (healthy individuals, n=4) was independently performed in the same experimental conditions with MSU, palmitate and palmitate+MSU stimulations. Volcano plots depicting the results of the Differential Expression Analysis comparing (a) palmitate vs control; (b) palmitate+MSU vs palmitate; (c) LPS vs RPMI and (d) LPS+MSU vs RPMI. X axis represents the log2 Fold Change and y axis the p value for each analyzed mRNA. (e) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of the top upregulated pathways in all comparisons. Infectious disease terms were excluded.

MSU crystals form as a result of hyperuricemia, a condition characterized by elevated serum urate levels, and are a key pathogenic factor in gout and related inflammatory diseases. Hyperuricemia is common in various metabolic disorders, including obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, highlighting the broad relevance of MSU crystal formation beyond classic gout. Importantly, MSU crystal deposits are not exclusive to symptomatic gout patients; studies report that about 20–30% of individuals with asymptomatic hyperuricemia harbor silent MSU crystal deposits detectable by ultrasound.[5,6,23] The presence of these asymptomatic deposits may matter because they are linked to systemic inflammation and increased cardiovascular risk, suggesting a subclinical phase of crystal-driven pathology that could potentially progress to gout or contribute to metabolic complications.

MSU crystals lead to inflammatory responses through incompletely clear mechanisms. Previous reports have consistently shown that sterile MSU crystals are not capable of inducing a significant inflammatory response,[13,21,24] while other studies have described ample inflammatory signatures associated to MSU crystal challenge.[16,17,25] Here, using four cohorts of patients with gout or controls, each consisting in more than 100 individuals each, we provide novel large datasets illustrating responses to MSU crystals in presence or absence of palmitate stimulation in fresh PBMCs. We show that MSU crystals alone, albeit in a minority of samples and at low concentrations, led to a small but significantly enhanced IL-1β production. At present, the sources of the observed variability in responses remain unclear, but it is plausible that a priming mechanism or genetic factors contribute to this phenomenon. Innate immune responses can vary significantly in intensity based on previous interactions that reprogram the metabolic state, therefore inducing a “primed” state.[26] Given the strong association between obesity, hyperuricemia and gout, fatty acids were proposed as priming agents when the synergy between MSU and fatty acids was first described by Joosten et al.[13] Urate itself was also proposed to be a priming factor as it was shown to reduce in vitro the IL-1Ra production, in a mechanism dependent on PRAS40 pathway.[21,27] In this study, we confirm the strong synergistic effect between palmitate and MSU crystals in several large cohorts.

The type of cells and experimental conditions influence the response to MSU significantly. Most studies that describe sterile MSU-induced IL-1β production were performed in THP-1 differentiated macrophages.[15,16,17] Typically, THP-1 monocytes are differentiated into macrophages with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), an agent that induces a strong response with nuclear translocation of NF-κB into the nucleus[28] and a strong pro-inflammatory transcriptomic signature characteristic for NF-κB signaling and other inflammatory signaling pathways.[29] PMA treated macrophages are significantly more responsive to inflammatory stimuli, with higher IL-1β and IL-6 production, increased phagocytic activity and reactive oxygen species.[30] Additionally, LPS priming is often used to activate the monocytic cell lines, which would also significantly increase pro-IL-1β expression.[31] A synergistic effect between LPS and MSU similar to the one observed with palmitate has also been described.[32] A recent study by Cobo et al[33] described a transcriptomic signature in M1 macrophages derived from human monocytes stimulated with M-CSF, which consisted in upregulation of genes involved in cytokine signaling, metabolic pathways, circadian clock and TLR4 signaling without upregulation of pro-IL-1β.

In our experiments, we employed freshly isolated PBMC stimulation assays as a representative model to evaluate monocyte responses, recognizing monocytes as a primary source of IL-1β secretion following initial local inflammatory triggers in gout. While there are many similarities between monocytes and the monocyte – derived macrophages, specific mechanisms have also been described, such as post-translational regulation of pro-IL-1β via p38 signaling specific to monocytes in response to MSU crystal stimulations, which did not occur in macrophages.[34]

The key finding observed here is the absence of significant transcriptomic changes associated with MSU crystals alone or in combination with other stimuli despite the previously documented increased IL-1β production and synergy with palmitate. While we cannot exclude minor changes that require a larger sample size to identify, this finding strongly indicates that the PBMC response to MSU crystals is largely regulated at the post-transcriptional level. Most likely, the main effect is NLRP3 inflammasome activation, which was already documented,[17] but other mechanisms cannot be excluded.

We also find that MSU crystals do not change the PBMC transcriptomic profile in combination with LPS. Unlike palmitate, LPS has a short-term effect, which is usually examined at 4 hours after stimulation,[35] however we were still able to observe the characteristic signature after 24 hours. The main rationale for choosing a 24-hour timepoint was because it reflects the peak IL-1β production induced by MSU crystals and palmitate, observed both in transcription of IL1B[36] and cytokine production of IL-1β.[37] Interestingly, in our experiments, palmitate and LPS produced a largely similar transcriptomic response, likely because both induce a NF-κB mediated response.[38,39]

Our methodological design has some important limitations. Firstly, transcriptomic analysis is based on PBMCs from 4 patients with gout and 4 controls, which constitutes a small sample size. Although the findings were technically validated through two independent analyses and biologically replicated in separate experiments across two different laboratories, the relatively small sample size limits the conclusiveness of the negative results. Moreover, another limitation is the 24h timepoint for assessing transcriptome changes, as it is known that transcriptomic changes in response to stimuli, such as LPS, peak at earlier timepoints, such as 4 hours.

Understanding the mechanisms that regulate inflammatory responses in hyperuricemia with MSU crystal deposition is essential for developing new clinically relevant markers and therapeutic targets. The absence of transcriptomic changes in PBMCs 24 hours after MSU stimulation indicates limited RNA biomarker utility in acute gout inflammation. This suggests post-transcriptional regulation and metabolic pathways could play larger roles, highlighting the need to explore these processes, especially in patients with metabolic comorbidities. From a therapeutic perspective, the identification of IL-1β as a central mediator in gout has led to the clinical use of IL-1β blockers, which are currently indicated for managing severe gout flares when other anti-inflammatory agents and colchicine are contraindicated. Therefore, it is critical to precisely elucidate how MSU crystals contribute to IL-1 inflammation to better combat the disease. Furthermore, it is crucial to recognize that MSU crystals alone are insufficient to trigger gout flares; additional factors are required. Identifying these co-triggers could enable novel preventive strategies that reduce reliance on lifelong urate-lowering therapy, especially in patients with obesity or metabolic comorbidities where flare risk is heightened.

In conclusion, here we report, in two independent analyses, that despite a consistent and strong synergistic effect of MSU crystals and TLR ligands to induce IL-1β, the transcriptomic signature associated to MSU crystal exposure in freshly isolated PBMCs is very limited. Reports on transcriptomic changes induced by MSU crystals in gout are conflicting and are subject to interpretation given the variability of experimental models and obtained results. Despite the advances in the field, the mechanism by which a gout flare is initiated remains one of the most important unanswered questions in gout pathophysiology. Our study points toward a predominant involvement of post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms in modulating the inflammatory response to MSU crystals in gout, particularly regarding IL-1β secretion in primary human mononuclear cells.