The study points the interplay between EBV infection and the epigenetic methylation machinery of the host cell in laryngeal carcinogenesis: changes in the 5-mC%, the hyperexpression of DNA-methyl-transferases and the methylation of the promoters of the investigated TSG. Notably, the methylation profile of PDLIM4 is the first time reported in this pathology, mainly associated with EBV infection.

Laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC) is the second most common head and neck malignancy worldwide. In 2020, higher incidence of LSCC was found in men compared with women (160.265 vs 24.350 new cases) [1]. In Romania in 2020, a 5-year incidence for all ages of 29.68% (per 100.000 people) of laryngeal cancer was reported, with 1922 new cases and 1108 deaths [2].

Epidemiological factors such as male gender, smoking habits and alcohol consumption, hypertension, and metabolic syndrome are associated with LSCC development and progression [3]. Additional studies suggest that human papillomavirus (HPV) and Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infections may contribute to LSCC [4]. EBV, a lifelong asymptomatic infection in B lymphocyte, has been linked to LSCC pathogenesis, with a meta-analysis showing nearly three times higher prevalence in EBV-infected individuals.

Genetic and epigenetic alterations play a major role in the LSCC onset and progression, with DNA methylation being crucial in both normal development and oncogenesis [5,6,7]. Mediated by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) such as DNMT1, DNMT3A and DNMT3B, this process primarily occurs at the CpG islands, in the gene promoters, leading to gene silencing, genomic instability and cancer development [8,9,10].

On the other hand, Saha et al. showed that oncogenic viruses, including EBV, are influenced by epigenetic changes in viral and cellular genomes in the infected cells [11]. In EBV-associated cancers, viral proteins can alter host epigenetic regulatory factors, leading to methylation of tumor suppressor genes (TSGs) and promoting tumorigenesis. The impact of EBV on tumor development varies depending on its latency programs in different cancers. For example, in nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC), the viral latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) expression increases the DNMT1 and DNMT3B levels, leading to the silencing of TSGs [12,13,14,15]. Multiple studies have reported frequent methylation of p16, MGMT, DAPK, TIMP3, RASSF1A, APC genes in the head and neck carcinomas (HNC) [16]. Additionally, promoter hypermethylation of TSGs, including p16, CDKN2A, PDCH17, E-cadherin, DAPK, MGMT, RASSF1, LZTS2 as well as WNT inhibitors (WIF1, DKK1, LKB1, PPP2R2B, RUNX3, SFRP1, SFRP2), has been identified as a potential diagnostic and prognostic marker in laryngeal carcinoma [17]. Based on these observations, we aimed to explore how EBV infection, a known risk factor for carcinogenesis, might influence DNA methylation in laryngeal carcinoma.

The study included 24 LSCC consecutive patients who underwent laryngeal surgery in the Department of Otorhinolaryngology from Coltea Clinical Hospital, Bucharest between March 2019 and February 2020. The clinical and TNM stages of neoplastic samples were classified according to UICC criteria in Department of Pathology. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (No. 279/11.02.2019), and the research was conducted ethically, with all study procedures being performed in accordance with World Medical Association's Declaration of Helsinki. From each subject, paired tissue biopsic samples (neoplastic and peri-neoplastic) were collected and preserved at −80°C until nucleic acids isolation.

DNA isolation from laryngeal tissues was performed using High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany), according to manufacturer's instructions. The concentration and purity of each DNA sample were determined using a NanoDrop ND1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., California, USA).

The quality of isolated DNA samples was verified by PCR for a house-keeping gene (β-globin) and amplicons (110 bps) were visualised in 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. PCR (conditions indicated in Table 1) was performed in 25 μl volume containing 5X PCR Go-Taq Green Flexi Buffer, 25 mM MgCl2, 10 mmol of each dNTPs, 5 U/μl Go-Taq DNA Polymerase (all from Promega, Wisconsin, USA), 10 μM of each β-globin forward and reverse primers and 200 ng of isolated DNA.

Total RNA extraction from tissues was performed using Trizol Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., California, USA). The samples were further purified with RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and stored at −80°C until use. The purity and concentration of each RNA sample were determined using NanoDrop ND1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., California, USA). The cDNA was synthesised using GoScript Reverse Transcription Kit (Promega, Wisconsin, USA) and each sample was stored at −20°C until further use. All protocols were according to each manufacturer' instructions.

The tumor samples were tested for the expression of two EBV genes, BZLF1 (BamHI Z fragment leftward open reading frame) and LMP1 (Latent membrane protein 1) using TaqMan assays. The primers used are listed in Table 1. qPCR reaction mix was performed in a 25 μl final volume (100 ng/μL cDNA, 1X TaqMan Universal Master Mix, 25 pmol of each BZLF1 and LMP1 forward and reverse primer and 10 pmol TaqMan probe) using iQ5 System (BioRad, California, USA). qPCR conditions for each EBV gene are shown in Table 1. Human beta-actin (VICTM/MGB probe) was used as a housekeeping gene (Applied Biosystems, California, USA).

Sequences of primers and thermocycling conditions

| Gene name [primers/probes reference] | Primer/Probe sequence | PCR technique Thermocycling conditions |

|---|---|---|

| β-globin [18] |

|

|

| BZLF1 [19] |

|

|

| LMP1 [19] |

|

|

| GAPDH [20] |

|

|

| PDLIM4 [21] |

|

|

| WIF1 [21] |

| |

| DAPK1 [this study] |

| |

| DNMT1 [20] |

|

|

| DNMT3B [this study] |

|

The DNMT1 and DNMT3B expression levels were analysed in neoplastic versus peri-neoplastic samples using GAPDH gene as a reference. qPCR was performed in 25 μl final volume with 100 ng/μl cDNA, Maxima SyBr Green/Fluorescein qPCR Master Mix 2x (Thermo Scientific Inc. California, USA), 30 μM of each forward and reverse primer on iQ5 System (BioRad, California, USA). Specific primer sequences and qPCR conditions are listed in Table 1. Fold change gene expression was estimated using 2−ΔΔCq method.

DNA sodium bisulfite treatment was performed on 700 ng of each isolated DNA using EpiTect Bisulfite kit (Qiagen, California, USA) and on 1000 ng of positive (CpGenome Universal Methylated DNA) and negative (CpGenome Universal Unmethylated DNA) DNA controls (Millipore, Massachusetts, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Treated DNA samples were stored at −20°C until use.

The three TSGs methylation profile (PDLIM4, DAPK1 and WIF1) in neoplastic versus peri-neoplastic tissues was analysed by q-methylation-specific-PCR method. The primers and thermocycling conditions are shown in Table 1.

Standard curves were build using serial dilutions (10 ng, 1 ng, 100 pg and 10 pg) of positive (fully methylated) and negative controls (completely unmethylated), respectively. DNA samples were diluted to a final concentration of 10 ng/μl, and PCR was performed in 25 μl final volume, using 12.5 μl FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master Mix-ROX (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Germany) and 10 μM primers. Concentration of methylated (M) and unmethylated (U) DNA for each sample was extrapolated using the standard curves and the methylation percentage was calculated according to the formula of Fackler et al. [22]: M=100×[ng methylated gene A/(ng methylated gene A + unmethylated gene A)], where total target gene DNA was taken as the sum of M+U.

Global DNA methylation level (5-mC%) was estimated on 100 ng DNA/well, using 5-mC DNA ELISA Kit (Zymo Research, California, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In each sample, 5-mC% was quantified (absorbance at 405 nm) using a standard curve generated with positive and negative controls, designed from the logarithmic second-order regression (R2), using the following formula: 5-mC%=e{(Absorbance-y-intercept)/Slope}.

The statistical data was analysed using GraphPad Prism 9.3 version. (Graph Pad Software Inc., California, USA). Statistical significance p was set to less than 0.05 for each type of analysis (Spearman correlation, linear regression and Mann-Whitney U test).

The study was performed on 24 paired tissue specimens, obtained from male LSCC patients (44 – 77 years old, mean 59.1, median 61) whose clinical and epidemiological characteristics are presented in Table 2.

The characteristics of investigated group

| Clinical characteristics | Number of cases [n (%)] | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | <65 / ≥65 | 11 (45.8%) / 13 (54.2%) |

| Smoking | Yes | 19 (79.2%) |

| Lymph node metastasis | Yes / No | 11 (45.8%) / 13 (54.2) |

| T stage | T1/T2 | 2/10 (8.3% / 41.7%) |

| T3/T4 | 9/3 (37.5% / 12.5%) | |

| N stage | N0/N1 | 5/6 (20.8% / 25%) |

| N2/N3 | 12/1 (50% / 4.2%) | |

| M stage | M0/M1 | 20/4 (83.3% / 16.7%) |

The global DNA methylation profile in laryngeal tumors was evaluated by assessing the (5-mC) percentage and quantifying the expression levels of key genes (DNMT1 and DNMT3B) involved in DNA methylation. Results indicated statistically significant differences (p=0.004) between 5-mC% in the neoplastic samples (0 – 81.28; median=5.66) vs peri-neoplastic ones (21.44 – 44.08; median=34.68), thus suggesting a global DNA hypomethylation in neoplastic laryngeal tissues.

Moreover, significant differences (p=0.04) for DNMT1 expression levels in neoplastic (median=3.009) vs. peri-neoplastic (median=1.183) but not for DNMT3B (p=ns, neoplastic median=−0.3476, peri-neoplastic median=−1.509) were obtained. Significantly differences regarding the levels of DNMT1 (p=0.0005), DNMT3B (p=0.0028), and 5mC% (p=0.0187) were found between smoking and non-smoking patients.

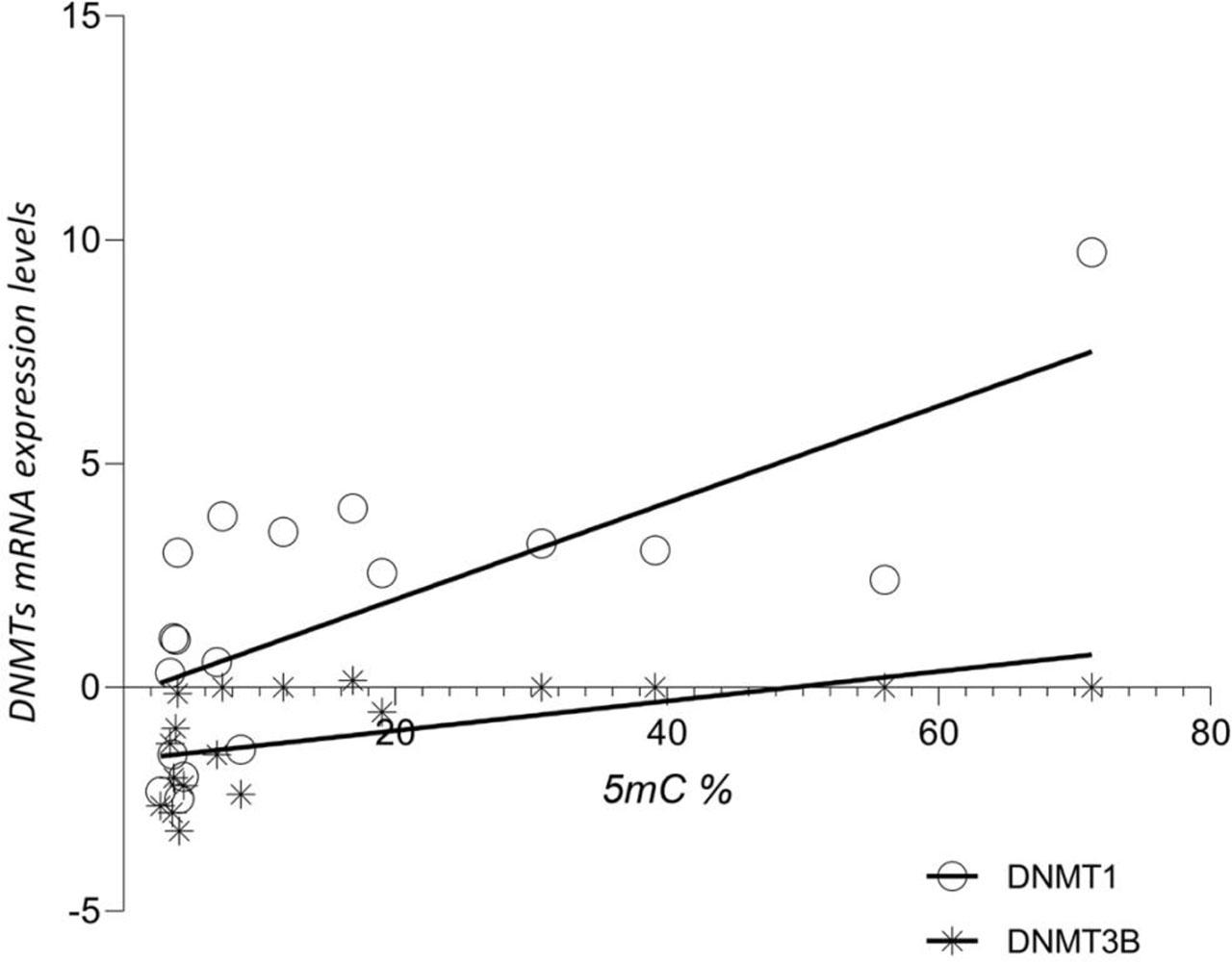

Using linear regression, we also found significant positive correlations between 5mC% and DNMTs (r=0.5153, p=0.0008 for DNMT1, r=0.3167, p=0.0154 for DNMT3B).

The relationship between 5mC% and the expression levels of DNMTs in neoplastic tissues.

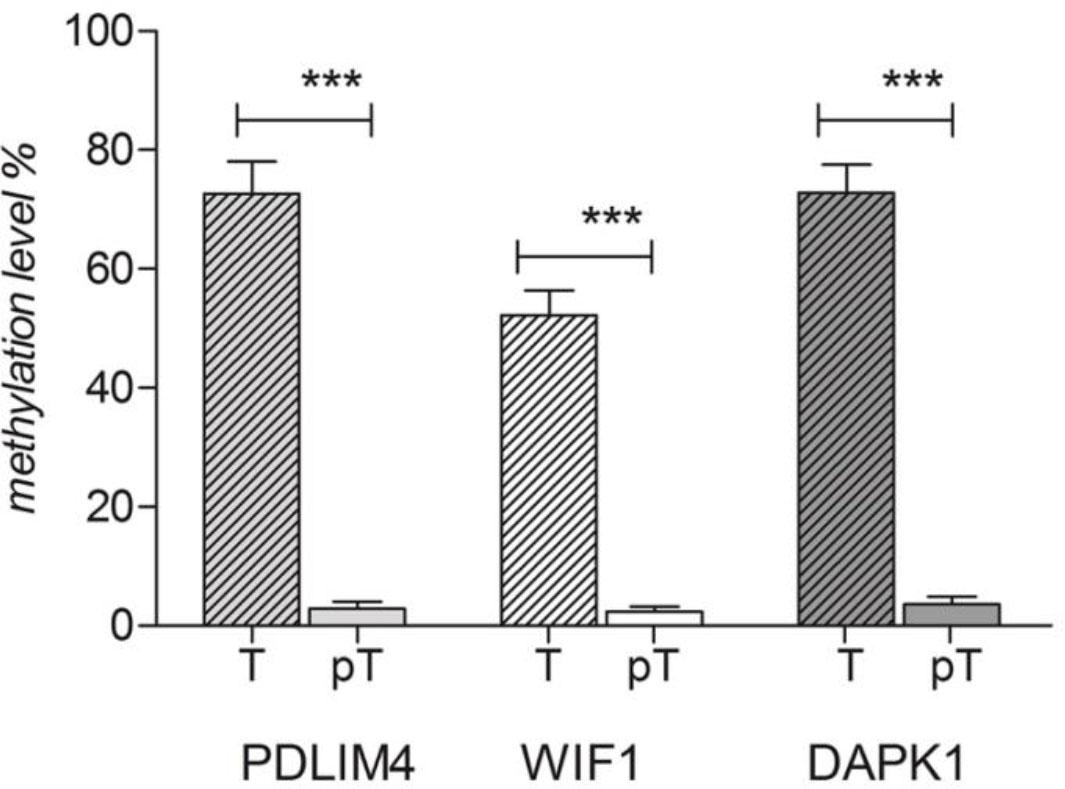

Three important TSGs, PDLIM4, DAPK1 and WIF1 were selected for a comparative evaluation of their promoter’s methylation profiles in tumoral and peritumoral laryngeal tissue samples. Using qMS-PCR, we observed that all investigated genes display significantly higher methylation levels in neoplastic samples versus peri-neoplastic ones (p<0.0001, for each gene) (Figure 2).

Methylation percentages of PDLIM4, DAPK1 and WIF 1 genes’ promoters in neoplastic (T) and peri-neoplastic (PT) laryngeal tissues.

The highest methylation percentage was found for the PDLIM4 gene promoter (neoplastic samples median=77.94 (27.84 – 99.93) vs peri-neoplastic pairs median=1.832 (0.1688 – 10.73)) followed by DAPK1 gene promoter (neoplastic samples median=75.68 (32.53 – 100) vs peri-neoplastic pairs median=2.114 (0.00–9.409)) and WIF1 gene promoter (neoplastic samples median=41.77 (8.229–87.20)) vs. peri-neoplastic pairs median=1.158 (0.5621–7.82)).

Analyzing the relationship between the methylation levels of the promoters of the three TSGs and 5-mC percent in neoplastic tissues (linear regression Pearson), we found a strong significant correlation between 5-mC% and PDLIM4 methylation, respectively between 5-mC% and DAPK1 methylation. (Table 3).

The correlation between the percent of global (5mC%) and local (TSGs promoters) methylation

| Parameter | PDLIM4 | WIF1 | DAPK1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson r | −0.4203 | −0.2904 | −0.3996 |

| 95% CI | −0.6743 to −0.07755 | −0.5763 to 0.05871 | −0.6604 to −0.05269 |

| P value (two-tailed) | 0.0186 | ns | 0.0259 |

BZLF1 and LMP1 viral genes were confirmed in the laryngeal tumors of 11 out of 24 patients included in the study. The clinical characteristics of EBV-positive and EBV-negative patients are detailed in Table 4. No significant associations were identified between clinical and epidemiological characteristics and the investigated markers in relation to EBV infection status.

Clinical characteristics of patients based on EBV infection status

| Clinical characteristics | EBV positive (n=11) | EBV negative (n=13) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 57–77 (median: 66) | 44–71 (median: 59) | |

| Smoking | Yes | 5 (20.8%) | 13 (54.2%) |

| T stage | T1-T2 | 3 (12.5%) | 9 (37.5%) |

| T3-T4 | 8 (33.3%) | 4 (16.6%) | |

| N stage | N0-N1 | 8 (33.3%) | 3 (12.5%) |

| N2-N3 | 3 (12.5%) | 10 (41.7%) | |

| M stage | M0-M1 | 11 (45.8%) | 13 (54.2%) |

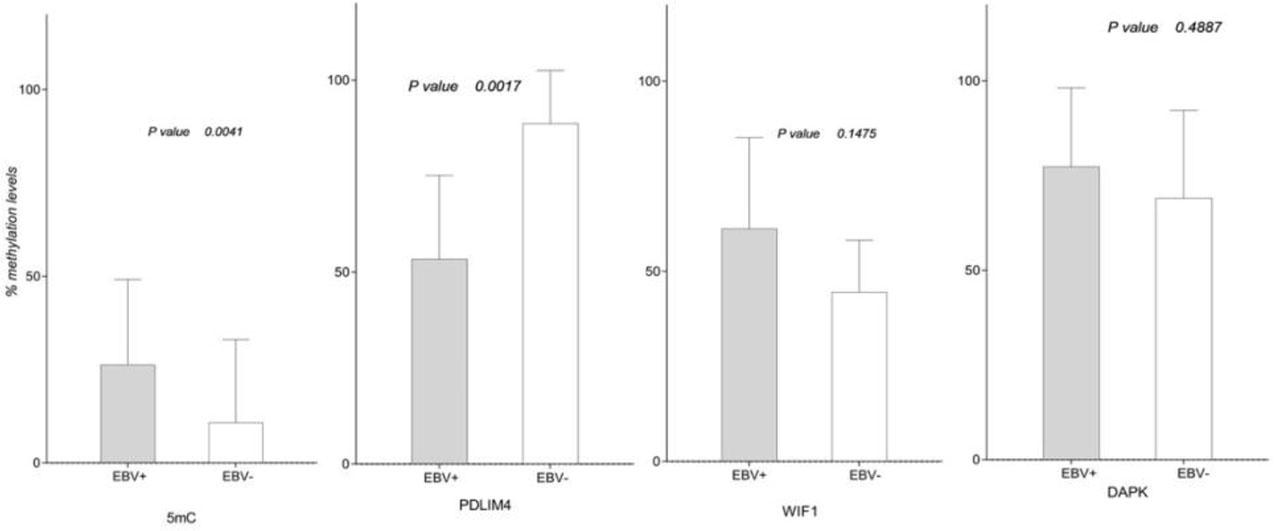

Therefore, all previously investigated molecular factors were analysed according to EBV status (Mann-Whitney U test) and the results are illustrated in Figure 3. Statistically significant differences between EBV-positive and EBV-negative cases were noticed for 5-mC% (p=0.0041) and PDLIM4 gene promoter methylation (p=0.0017). Interestingly, all other investigated markers showed increased values in EBV-positive samples vs. the negative ones, except for PDLIM4 gene promoter that had a significantly lower methylation percentages in EBV-positive samples (median/min-max: 48.09 / 27.84 – 98.79) compared to EBV-negative ones (median/min-max: 94.35 / 62.63–99.93).

Global (5-mC%) and local methylation profile (TSGs promoters methylation) in EBV-positive compared to EBV-negative laryngeal tumors.

Likewise, DNMT1 and DNMT3B expression levels showed significant differences between EBV-positive and EBV-negative neoplastic tissue samples (p=0.0018, respectively p=0.0017) with higher values in cases of viral infection (DNMT1 median EBV+/EBV−: 3.038 / −1.388; DNMT3B median EBV+/EBV− : 0.00 /−2.289).

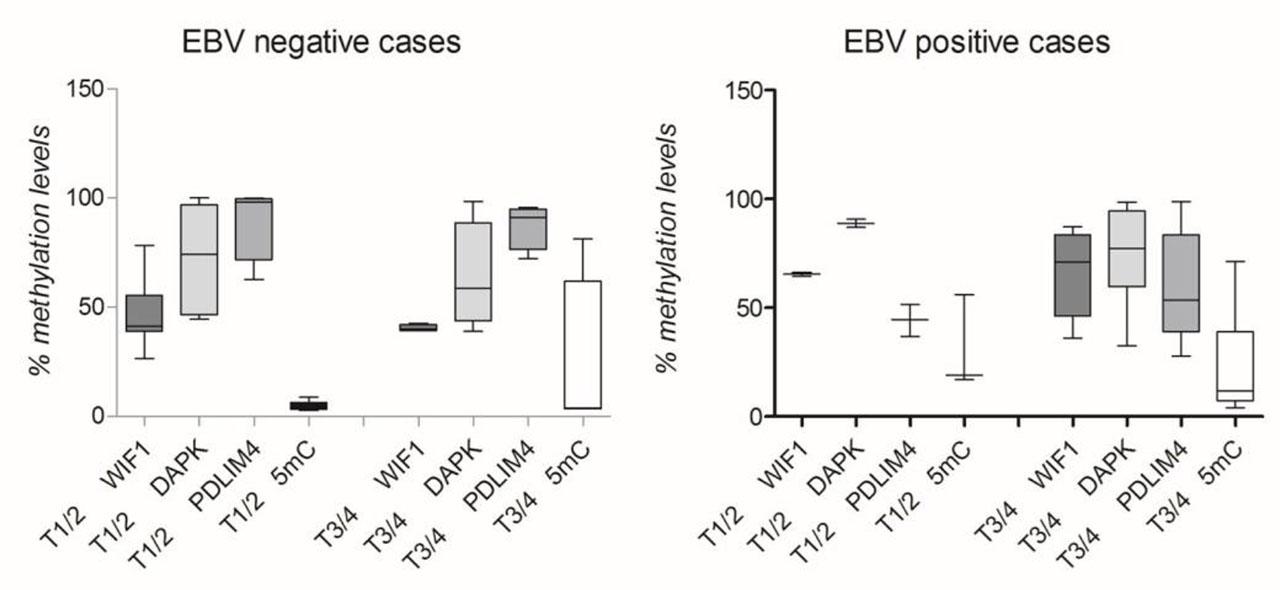

Potential changes in the investigated parameters were identified according to EBV status and TNM classification. Significant differences between EBV-positive and EBV-negative cases based on tumor stage (T) for two parameters were obtained (Figure 4), specifically, for 5-mC% in both T1/T2 stages (p=0.0364) and T3/T4 stages (p=0.0275). Also, PDLIM4 promoter methylation was significantly different between positive and negative cases, but only in T1/T2 stages (p=0.0121).

Investigated parameters in EBV positive (A) and EBV negative laryngeal tissue samples (B), according to T stage.

Our study investigated a potential cooperation between EBV and methylation status in laryngeal carcinoma. As in other cancers, the LSCC epigenetic machinery, in particular DNA methylation, is altered. Global hypomethylation could be responsible for chromosomal instability, aberrant gene expression occurrence in tumor cells being associated with oncogenesis [23]. This epigenetic process is associated with low levels of DNA methylation in large genome regions, being found in both repetitive elements and genes bodies [24].

In our study, global DNA hypomethylation (assessed by the 5-mC percentage in DNA) was found in neoplastic laryngeal samples vs non-neoplastic ones, this could be determined by the carcinogenic events, including smoking (79.16 % of the enrolled patients being smokers). Also, Stembalska et al. obtained similar results, who, in addition, showed the absence of this marker in the LSCC patients’ blood samples [25]. Our results were also confirmed by the Ferraguti G. et al. report in which the global hypomethylation was significantly associated with smoking, alcohol use and tumor grade in two thirds of head and neck carcinomas [26].

In our study, we observed that neoplastic tissues displayed higher DNMT1 and DNMT3B expression levels compared with non-neoplastic ones. One study highlighted a more increased expression of DNMT1 in HNC samples versus normal samples, its levels being linked to various risk factors (higher tumor grade, male gender, age under 60 yo and Caucasian ethnicity). According to this study, the DNMT1 expression was depicted as an important diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for HNC [27]. We also focused on local methylation assessment by evaluating the PDLIM4, WIF1 and DAPK1 genes promoters’ methylation patterns; in our research higher methylation percents for all three TSGs promoters were found in tumors (the highest percent was observed for PDLIM4 gene). To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to mention the PDLIM4 gene promoter methylation in LSCC.

DAPK1 gene, an apoptotic signaling regulator, is known to be repressively modulated by hypermethylation in various cancers [23]. DAPK hypermethylation was mainly observed in laryngeal tumor tissues (87%), this epigenetic event could be related to the early oncogenesis in head and neck carcinomas [28]. Liu Y. et al. suggested that DAPK promoter hypermethylation could be a minimally invasive biomarker for early detection of oral squamous cell carcinoma, its increased hypermethylation level being also found in blood samples [29]. DAPK1 promoter methylation was associated with lymph node metastasis but also with decreased risk of death, in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma [30].

The analysis of the methylation status of several WNT cascade inhibitors (DKK1, LKB1, PPP2R2B, RUNX3, SFRP1, SFRP2, and WIF-1) in 26 LSCC cell lines and 28 primary LSCC samples, showed that 50% of cell lines and 70% of primary tumor samples displayed promoter hypermethylation in at least four genes. The WIF1 and PPP2R2B hypermethylation were associated with longer survival [31]. On the other hand, the WNT pathway antagonists (SFRP1–5, DKK1–3, WIF1, DACH1, and PPP2R2B) methylation was associated with worse prognosis, being frequently observed in HNC [32].

Literature studies showed that low positive rates of both circulating EBV DNA and serological EBV markers in peripheral blood could not confirm EBV-positive LSCC [5]. Therefore, in this study, EBV-positive samples were classified as those that expressed viral markers (BZLF1 and LMP1) in RNA isolates obtained from tumor laryngeal tissues. BZLF1 is a marker of lytic replication while LMP1 is a latent gene, strongly associated with EBV oncogenic properties. Stratifying the laryngeal tumor samples according to the presence of EBV markers, 5mC% was found increased in samples with viral infection, the difference between positive and negative EBV samples being significant. Moreover, the DNMTs expression levels were significantly higher in EBV-positive samples, an event generally considered a hallmark of cancer [33]. DNMTs act collectively in oncogenesis: DNMT3B expression being considered a cofactor significantly related to lymph node involvement, disease recurrence and reduced survival rate risk in patients with pathological stage III–IV oral cancer [34]. Increased expression of DNMT1 was also reported in NPC, resulting in E-cadherin gene (CDH1) hypermethylation, and DNMT3B increasing expression in NF-kB pathway LMP1-mediated [35].

In EBV-positive tumors, we found an important increase of DNMT1 and DNMT3B expression. After infection, EBV genome hypermethylation limits the lytic genes expression and induces a latent status, which modulates DNMTs expression and TSGs promoters, leading to cell cycle alteration and cell transformation, thus promoting EBV-associated neoplasms development via epigenetic mechanisms [15]. Furthermore, our results showed that PDLIM4 promoter methylation levels are significantly lower in EBV-positive samples vs EBV-negative ones. This observation is also sustained by Saha et al. study that reported this gene presented a 15-days fluctuating methylation profile post-EBV infection of B lymphocytes [11].

In the studied EBV-positive neoplastic samples, higher WIF1 and DAPK1 methylation values were found. A five-gene (including WIF1) methylation panel was reported to allow discrimination between NPC and non-NPC patients (98% rate of detection) [36]. Additionally, WIF1 and DAPK1 were included in a four-gene methylation panel that in correlation with EBV DNA test offers very high sensitivity in the NPC early detection [37]. These data support the hypothesis that WIF1 and DAPK1 are subjected to methylation in NPC, including EBV-positive cases.

The impact of EBV infection on methylation is highlighted in our study, especially when tumor stage is taking into account. Thus, the aberrant DNA methylation sustained by EBV infection was confirmed by significantly higher 5-mC percent in both between T1/T2 and T3/T4 in EBV-positive vs. negative ones. Also, differences between the PDLIM4 methylation percentage and EBV status in low tumor stages (T1/T2) were found, with decreasing values obtained for infected samples.

The global methylation (5-mC%) status, the three promoters' genes methylation profile and the two-methylation enzyme-modifiers expression could constitute potential diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in the EBV-positive laryngeal cancer. The main limitation of this study was the small cohort of laryngeal carcinoma patients and the limited number of EBV-positive cases. Additionally, financial constraints partially impacted sample processing, highlighting the need for a larger sample size to achieve more comprehensive and reliable results.

EBV plays a significant role in the TSGs methylation, thus contributing to these epigenetic changes leading to oncogenesis initiation and progression. TSGs hypermethylation and global DNA hypomethylation constitute distinctive and important epigenetic signatures in cancers, including laryngeal carcinoma.

The three TSGs methylation patterns (PDLIM4, WIF1, and DAPK1) may play a role in laryngeal tumorigenesis. The interplay between EBV infection and these epigenetic mechanisms could be more effectively illustrated in future studies. Notably, our study highlighted a correlation between EBV and epigenetic changes in laryngeal carcinoma.