Tides, winds, and waves can result in the natural formation of sea foams in aquatic environments. These well-known foams are formed when the surf mixes dissolved organic matter and other particles in seawater: salt, dead algae, pollutants, proteins, and fats that are continuously agitated by the constant movement of water (National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration, 2013). An abundance of foams can occur due to the die-offs of aquatic plants, large algal blooms, or other conditions that decrease surface tension in water. Foams occurring as a result of algal blooms have ranged from Southern Australia to California (Murray and Gaiani, 2025). Foams, however, are not only found in oceans; they can also reside in streams, wetlands, bog lakes, productive lakes, bays, and woody areas (Schilling and Zessner, 2011; Department of Environmental Quality, 2016).

Sea foams are usually indicators of a productive ecosystem and accommodate many different types of microorganisms such as bacteria, protists, algae, copepods, polychaetes, and larvae (Harold and Schlighting, 1971; Rahlff et al., 2021). Yet, depending on the inhabiting microorganisms’ toxicities, sea foams can introduce many different risks to beachgoers and coastal environments. If harmful algal blooms (HABs) decay near the shore, resulting foams can carry and transmit toxic dinoflagellates and diatoms into the air (NOAA, 2013). Toxins are dispersed into an aerosol when short-lived popping sea foam bubbles are volatilized. The contaminated aerosol can then spread toxins inland and harm nearby organisms by causing eye irritation or worsening respiratory conditions (Fleming et al., 2005). Possible occurrences of bacterial microorganisms such as Staphylococci or Streptococci sp., for example, may be found in foams and can be harmful to the respiratory system and induce asthma conditions (Cappelletty, 1998; Earl et al., 2015). As waters become warmer, nutrient rich, and polluted, more common HABs can continuously introduce contaminated foams into the environment. Additionally, foams can accumulate high concentrations of bacteria due to coastal pollution and foam aerosol production can become more dangerous in the future (Gobalakrishnan et al., 2014).

Sea foams can often be spotted along coastlines such as the New Jersey coast, which spans about 130 miles long and meets the Atlantic Ocean (Stockton University Coastal Research Center, 2022). Many water bodies along or near the New Jersey coast have experienced closures due to high bacterial levels originating from differing wind conditions, surface currents, and tides that transport waterborne bacteria. Heavy rainstorms can spread bacteria and nutrients into New Jersey waters due to runoff from animal waste, wildlife, and fertilizers. Recreational beaches are also impacted by the movement of stormwater through outfall pipes (New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, 2022).

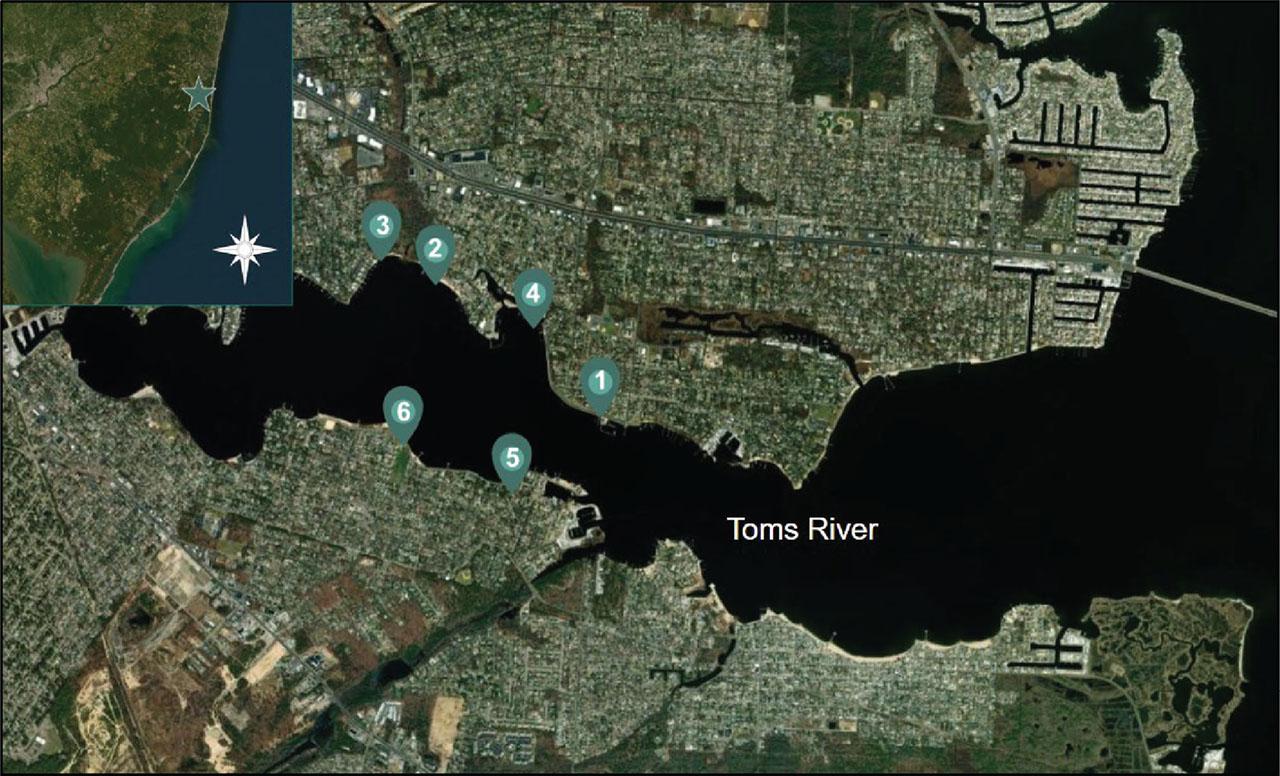

A preliminary study was conducted from 2021 to 2022 in which sea foams collected from six sites along the Toms River in northern Barnegat Bay in Ocean County, New Jersey contained high levels of Escherichia coli (E. coli) bacteria (Table 1; Figure 1). In this study, more common recreational bay and ocean beaches in Barnegat Bay were utilized as sampling locations: Seaside Park, Seaside Heights, and Lavallette. At these sites, bacteria testing was performed for foams, waters, coastal atmospheres, and foam aerosols. The objective of this study was to determine if foams along the New Jersey coast were able to volatilize concentrated amounts of residing bacteria into their aerosols and simplify foam aerosol sampling methods. It was hypothesized that foams would display higher concentrations of bacteria compared to their residing waters and resulting aerosols.

Geomean Escherichia coli (E. coli) coliforms found at each Toms River, New Jersey, USA sampling site in the preliminary study (2021–2022).

| Site Name | Island Heights | Money Island | Brown Rec Area | Island Beach | Station Ave East | Pine Beach |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site # | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Geomean E. coli Coliforms | 1253.0 | <0.1 | 365.0 | 143.1 | 15.8 | <0.1 |

Six study sites utilized in the preliminary study (2021–2022) that identified bacteria-containing sea foams in the Toms River, NJ (northern Barnegat Bay, Table 1). Mapping was performed using the ArcGIS software.

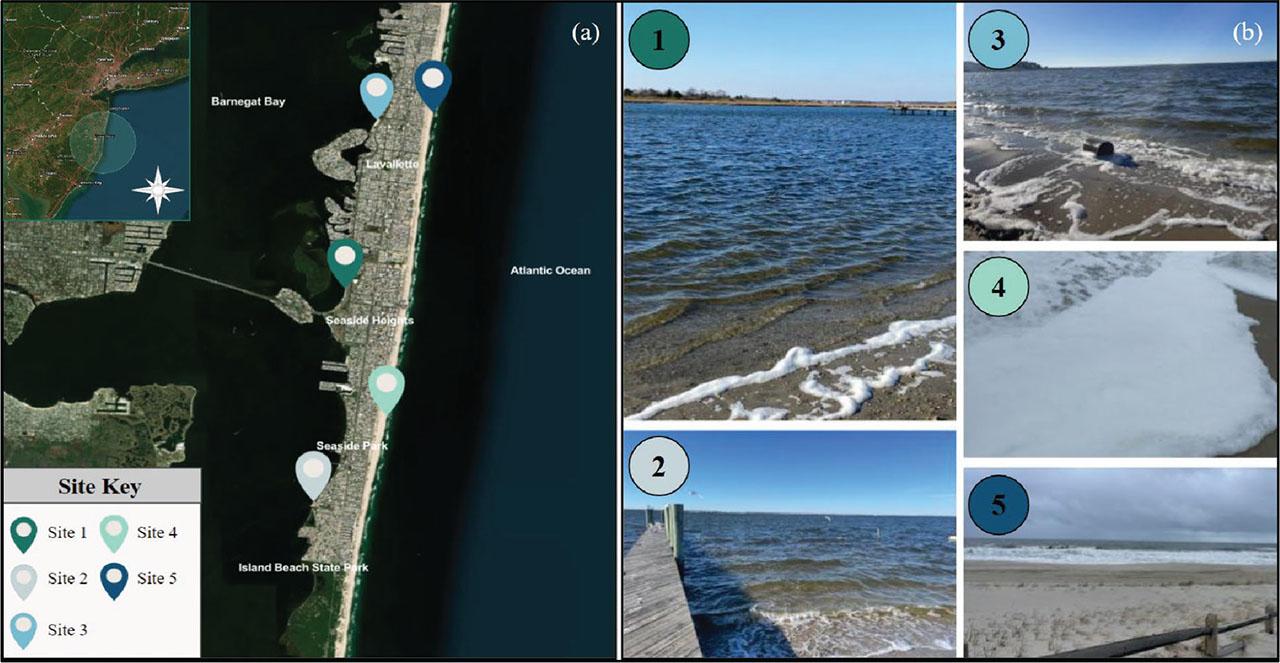

Sample collection was conducted from 19 November to 11 December 2022. A total of five collection sites along the New Jersey Shore were utilized, including water bodies along the mainland shoreline and barrier island shoreline: northern Barnegat Bay, Lavallette, Seaside Heights, and Seaside Park shores. Sites one, two, and three were all located along Barnegat Bay, and sites four and five were beaches located along the Atlantic Ocean (Figure 2). Prevailing winds, weather conditions, and foam availability affected chosen collection sites, and collection was concluded after a total of 75 samples of water, foam, foam aerosol, and controlled air samples were collected. Sampling was conducted when temperatures and other conditions remained stable with no precipitation, no extreme weather events, ∼5 to 10 °C air temperatures, and ∼6 to 10 °C water temperatures.

(a-b). (a) The five sites utilized for collection that ranged from Lavallette to Seaside Park, New Jersey (Table 2). Mapping was performed using the ArcGIS software. (b) Photographs of the five collection sites and examples of foams collected there.

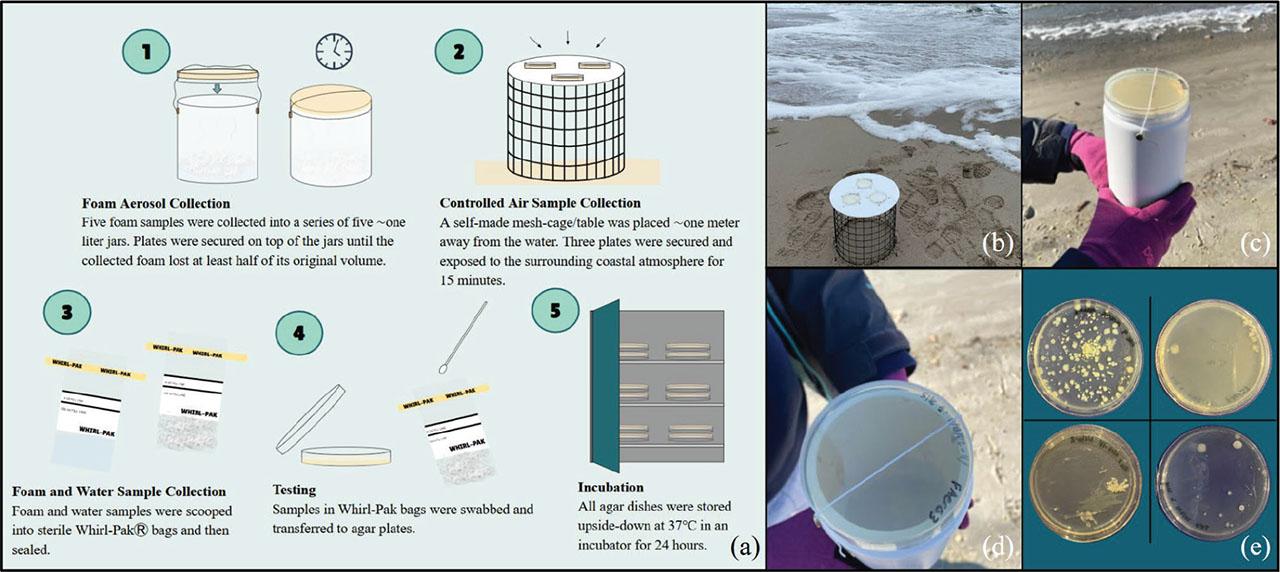

Novel sampling and testing techniques were utilized to conduct and simplify foam and foam aerosol bacterial sampling. Prior to sampling, 15 agar plates were poured and solidified with Luria Broth Agar, and all collection jars and tools utilized were disinfected with a 10% bleach solution. Data for environmental parameters was collected in the field: GPS coordinates, observations, salinity, tide conditions, weather conditions, precipitation conditions, wind speed and direction, water temperature, atmospheric pressure, and air temperature (Table 2). At each site, five 100 mL foam and five 100 mL water samples were collected for subsequent bacterial testing in sterile Whirl-Pak® bags (Nasco Sampling LLC, Chicago, Illinois, United States). Samples were stored in an ice cooler until testing to prevent contamination of samples. An additional five samples of foam were collected into a series of five one-litre jars. Each jar was filled with ∼350 mL of foam and premade agar plates were placed upside down and secured on each jar opening. Agar plates were thus passively cultured as foams volatilized in each jar (Figures 3 c,d). Agar plates were cultured until the collected foam lost at least half of its original volume, and the time the sample took to satisfy this was recorded. To quantify bacteria in the surrounding coastal air (controlled air samples), three premade agar dishes were secured on a self-made mesh table (Figure 3b). The mesh table was placed approximately a meter from the water and secured agar plates were exposed to the surrounding atmosphere for 15 minutes. Cultured dishes were stored in an ice cooler during transportation.

(a-e). (a) Illustrated methodological process. (b) Coastal air sample passive culturing of coastal air samples. (c,d) Foam aerosol collection method. (e) Examples of Coliforms grown on foam (top left), foam aerosol (top right), water (bottom left), and coastal air (bottom right) plates.

Locations sampled and field conditions recorded at each site during sampling.

| Site # | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site Name | Hancock Ave, Seaside Heights | 13th Ave Pier Seaside Park | Centennial Park, Lavalette | F Street Seaside Park | Brown Ave, Lavalette |

| Site Location Type | Barnegat Bay | Barnegat Bay | Barnegat Bay | Atlantic Ocean | Atlantic Ocean |

| Latitude | 40.025188 N | 39.9267851 N | 39.969393 N | 39.92726 N | 39.979813 N |

| Longitude | −74.0541903 W | −74.1337496 W | −74.073158 W | −74.07693 W | −74.064137 W |

| Salinity (ppt) | 20.0 | 19.8 | 18.8 | 27.8 | 28.9 |

| Water Temp (°C) | 7.5 | 6.4 | 7.6 | 8.8 | 7.8 |

| Air Temp (°C) | 5.0 | 13.3 | 12.8 | 8.3 | 8.3 |

| Wind Speed (mph) | 17 | 14 | 14 | 15 | 15 |

| Wind Direction | WSW | W | W | ENE | ENE |

| Tide | Low | High | High | High | High |

| Pressure (psi) | 30.20 | 30.05 | 30.03 | 30.21 | 30.18 |

| Precipitation | None reported | Previous day | Previous day | Previous night/later that day | Previous night/later that day |

| Time for Foams to Vaporize (min) | 45 | 43 | 50 | 41 | 42 |

All bacteria analysis was conducted in the MATES school laboratory using standard laboratory conditions, which included wearing gloves while working with agar plates. All surfaces were disinfected with a 10% bleach solution prior to bacterial testing. Foam, or disintegrated foam residue, and water samples in the 100 mL Whirl-Pak® bags were swabbed and transferred to agar dishes with sterile cotton swabs. Plates were “clam shelled” (minimally lifted) during swabbing to limit exposure and contamination of agar dishes. All plates were stored upside-down in an incubator set to 37 °C for 24 hours.

Coliforms in all cultured dishes were counted using a cell count grid. Bacterial microorganisms Staphylococci sp. and Streptococci sp. were identified and quantified (Colony Forming Units (CFU)) utilizing comparisons to colony morphology photographs by Earl et al. (2015), Zhu et al. (2015), and Chang et al. (2016). Geomeans were used to analyze bacteria data to account for bacterial variability and exponential growth. Single Factor ANOVA and Post-Hoc Tukey analyses were conducted to determine significant differences among bacteria in foams, foam aerosols, waters, and coastal atmospheres. Multiple Regression analyses were used to examine relationships between the following variables: salinity and bacteria in foam aerosols, salinity and bacteria in coastal atmospheres, bacteria in foams and their resulting aerosols, and bacteria in waters and their foams. A Two-Sample T-test assuming unequal variances was used to denote significant differences between foams, foam aerosols, and coastal atmospheres on Atlantic Ocean and Barnegat Bay shorelines. An alpha of 0.05 or less was used to determine significance for all analyses.

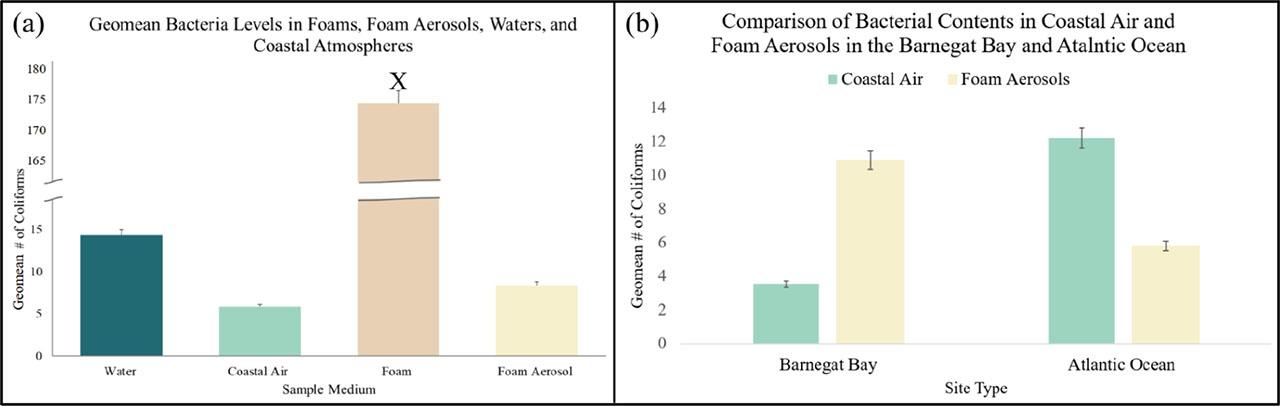

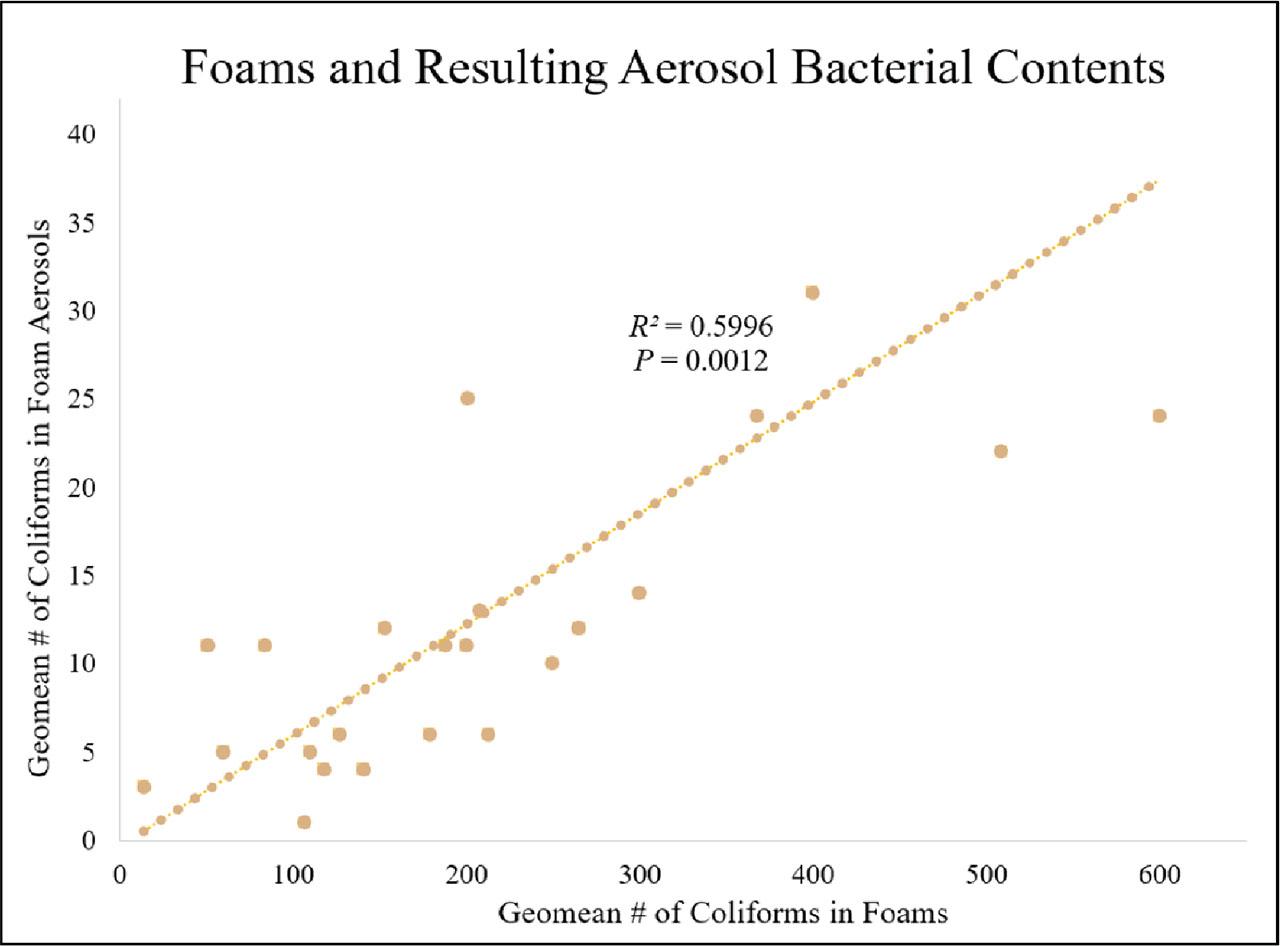

Amongst the five sampling sites, geomean bacteria counts ranged from 3.9 to 39.4 Coliforms in water, 91.3 to 453.7 Coliforms in foams, 2.5 to 18.1 Coliforms in coastal air (control), and 5.3 to 11.3 Coliforms in foam aerosols. Foams possessed significantly higher bacterial levels (P < 0.001) compared to their water, air, and aerosol counterparts (Figure 4a). Foams from Barnegat Bay were found to have significantly higher bacterial contents than foams sampled from the Atlantic Ocean (P = 0.0083, Barnegat Bay: 239.6 ± 173.1; Atlantic Ocean: 113.5 ± 81.2, ± 0.05, n = 25). Significantly higher bacterial levels were found in Barnegat Bay foam aerosols than in the surrounding coastal atmosphere (P = 0.0152), while higher geomean Coliforms were found in Atlantic Ocean coastal atmospheres than in oceanic foam aerosols (P = 0.1915) (Figure 4b). A significant relationship between salinity levels, controlled air, and foam aerosols was also found; as salinity increased, bacterial levels in foam aerosol decreased (R2= 0.9755, P = 0.0016, n = 25), and bacteria in coastal air increased (R2= 0.7194, P = 0.0694, n = 15). A significant relationship between foams and foam aerosols was also determined; as bacterial levels in foams increased, so did bacteria in their resulting aerosols (Figure 5). A weak relation, however, between bacteria in waters and their inhabiting foams was examined (R2 = 0.3878, P = 0.2618, n = 35).

(a,b). (a) Geomean bacterial levels found in all sample types collected from 19 November 2022 to 11 December 2022; foams (X) contained significantly higher amounts of bacteria compared to their aerosol, water, and coastal atmospheric counterparts (P < 0.001, Water: 14.3 ± 16.9; Coastal Air: 5.8 ± 6.3; Foam: 177.7 ± 151.7; Foam Aerosol: 8.4 ± 2.8, ± 0.05, n = 75). (b) Barnegat Bay sites had significantly higher bacterial concentrations in foam aerosols than in their surrounding coastal atmospheres (P = 0.0152, Coastal Air: 3.5 ± 6.8; Foam Aerosol: 15.4 ± 10.8), while Atlantic Ocean sites had higher coastal air Coliform counts than in their respective foam aerosols (P = 0.1915, Coastal Air: 12.2 ± 17.0; Foam Aerosol: 5.8 ± 3.2, ± 0.05, n = 60).

A significant relationship between bacterial contents (# of Coliforms) in foams and their resulting aerosols; as bacteria levels in the foams increased, bacteria levels in their resulting aerosols also increased (R2 = 0.5996, P = 0.0012, n = 25).

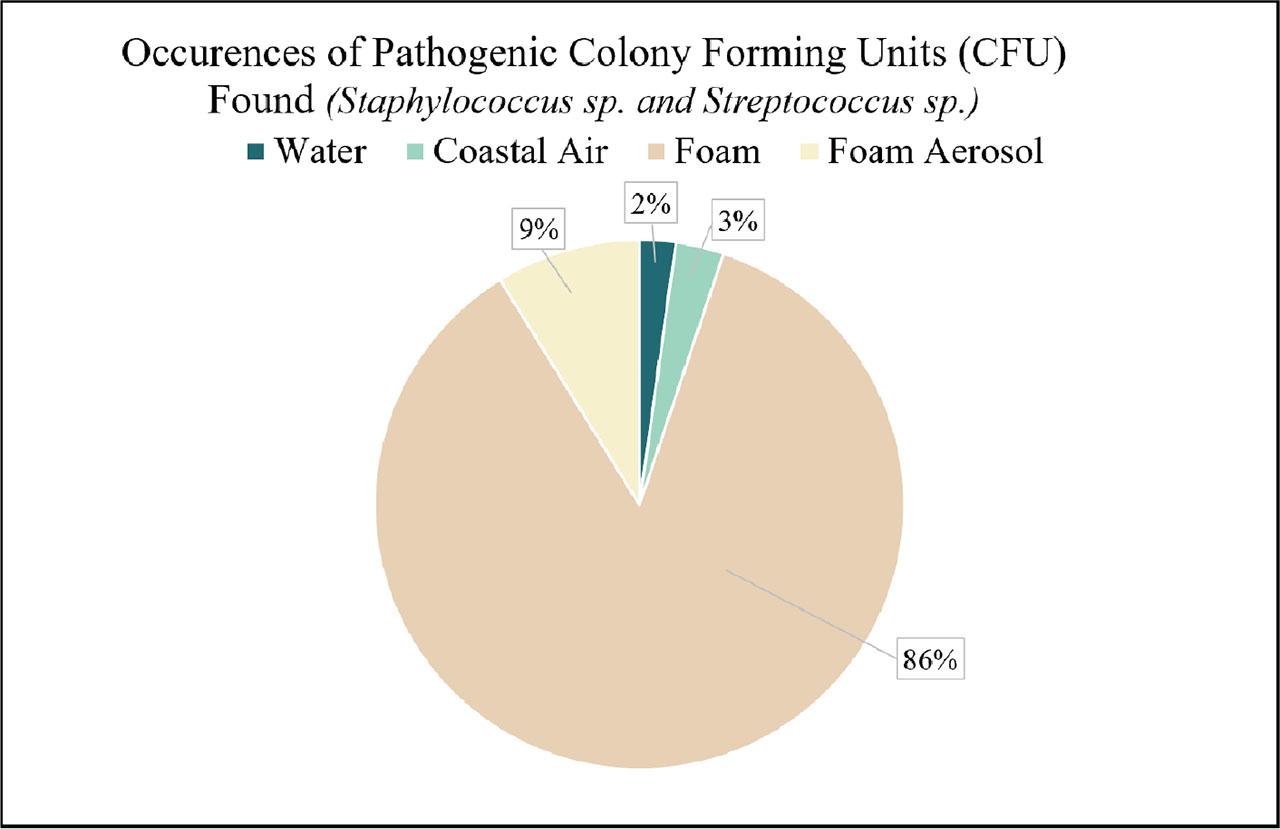

Identifications of respiratory harming bacteria, Staphylococcus sp. and Streptococcus sp., made up approximately 2.4 % of all water bacteria, 3.1% of all air sample bacteria, 3.5% of foam bacteria, and 2.1% of foam aerosol bacteria (CFU). Out of all possible occurrences of Staphylococci and Streptococci, 86% or 23.4 CFU of these genera were found in foam samples (Figure 6). Lastly, foams possessed the most diverse colony morphology, and circular colony shapes were the most prevalent shape found in all sample types (Figure 7).

An analysis of the potential identifications of respiratory harming, pathogenic Staphylococci and Streptococci genera. Respiratory harming bacteria represented themselves in mostly foam samples (86% of all Staphylococci and Streptococci bacteria were found in foams). The remaining 9% occurrence of pathogenic bacteria that were found in aerosols suggest that foams can successfully pass these genera to airborne conditions.

Quantified colony shapes (circular, irregular, and punctiform) found in all four sample types. Foam samples can be observed to have the most variety of colony morphology, containing all three of the most prevalent bacteria shapes found. Circular colonies were the most common colony shape found across all four sample types (± 0.05, n = 75).

Many inferences can now be made about the bacteria in foams and how bacteria transfers to other mediums found in coastal environments. Sites along the Atlantic Ocean possessed higher bacteria levels in controlled air samples than in their corresponding foam aerosol samples due to the presence of surrounding sea sprays at oceanic sites (Figure 4b). A recent study conducted by Pendergraft et al. (2023) investigated bacterial transfer from polluted waters to sea sprays in an area south of San Diego in the United States, where a wastewater treatment system sent untreated sewage into the Tijuana River that flowed into the Pacific Ocean. Bacteria, viruses, and chemical compounds from the polluted sea water were found in sea sprays, which were formed predominantly by breaking waves. This aerosolization of raw sewage can introduce threats to not only beachgoers and swimmers but also to surrounding coastal environments via wind. Resembling sea spray, this study also found that foam aerosols can transfer their residing bacteria into airborne conditions, as foams with high bacterial levels (∼300 to 500 Coliforms) resulted in foam aerosols with higher bacteria levels (∼20 to 30 Coliforms) (Figure 5). Although this study was conducted in cooler temperatures, the presence of bacteria in foam aerosols was still found. Future studies which can be conducted in the summer, a more ecologically active period, would help to determine the extent of bacterial presence in foams and their impact on health-related issues. As more contaminated foams materialize near beaches, resulting foam aerosols will introduce more microbial contents into their surroundings, which can also be noxious to surrounding organisms and communities (Gonzalez-Martin, 2019).

Bacterial levels in waters were found to be loosely related to bacterial concentrations in foams. These unanticipated findings suggest that other factors such as surrounding vegetation, sediment particles, and winds could affect bacterial growth in foams. Foams that were observed to be free-flowing, current-driven (oceanic foams) may be spots where bacteria sporadically linger, while more viscous foams (bay foams) can amass bacteria over time. In agricultural settings, vegetation has also been found to emit airborne bacteria, thus a higher presence of surrounding vegetation at Barnegat Bay sites may have aided bacterial accumulation in foams (Lindemann et al., 1982). In addition, wind speed and direction may have played a role in bacteria accumulation in foams. On days where foams were sampled from the Barnegat Bay, wind speeds were strong (14 to 17 mph) and typically originated from the West direction pushing waters directly onto the bay shoreline. Strong, targeted winds can transport areas of local airborne bacteria to shorelines, which may have aided bay foams with bacterial collection (Jacob et al., 2023). Wind and foam bacteria interactions also emphasizes the need for future studies as wind speeds continue to increase due to climate change (Li, 2023). Bay waters also typically accommodate more bacteria than saltwater and oceanic areas (Staley and Sadowsky, 2016).

Bacteria in surrounding coastal waters are often perceived exclusively as waterborne issues (Pendergraft et al. 2023); yet many respiratory threatening, pathogenic bacteria were potentially identified in foams and their aerosols in this study. Identifications of Staphylococcus sp. and Streptococcus sp. were not concentrated; only about 3.5% of quantified foam bacteria was Staphylococcus sp. or Streptococcus sp.. Nonetheless, possible exposure to Staphylococci or Streptococci can impose an increased risk or severity of asthma and induce wheezing in children (Earl et al., 2015), and the transfer of these bacterial genera from foams to aerosols is therefore dangerous to shorelines. Since it is difficult to obtain the species level of identification regarding Staphylococci and Streptococci bacteria, it would be beneficial to obtain DNA testing in the future to definitively suggest the presence of Staphylococci and Streptococci and their respective species (Cho and Tiedje, 2001).

The previous hypothesis that foams would exhibit the highest concentration of bacteria compared to waters, foam aerosols, and coastal atmospheres was supported. A significant relationship between bacteria in foams and their resulting aerosols was also found, further supporting the hypothesis that foams would have the ability to volatilize residing bacteria. This study can assist with monitoring the safety of coastal waters and their atmospheres; however, it can be expanded upon in the future by utilizing bacterial staining or DNA analysis to confirm the presence of Staphylococcus sp. and Streptococcus sp., performing testing on coastal atmospheres and foam aerosols at differing distances, and replicating this study during the warmer months of the year. This study, along with the identification and quantification of bacteria from aerosol-emitting foams, is crucial to maintaining the safety of ever-changing coastal areas.