Solid propellants are high-energy materials containing oxidizers and high-energy fuels, as well as high-density composite materials. These propellants can sustain combustion and generate high temperatures and thrust in the absence of external oxidizers [1,2,3,4,5]. Currently, they are primarily used in missiles, rocket engines, and aerospace launch vehicles.

Solid propellants are categorized based on their composition into double-base, modified, and multi-component propellants. Modified propellants, positioned between double-base and multi-component propellants, primarily include oxidizers such as cyclotrimethylenetrinitramine (RDX), ammonium perchlorate (AP), and cyclotetramethylene-tetranitramine (HMX). They also contain metal powders like magnesium, aluminum, beryllium, and boron. When combined with combustion catalysts and stabilizers, these components are encapsulated in a binder, forming the solid propellant [6,7,8,9]. The development of solid propellants is advancing rapidly, with a focus on high energy and low cost. Their main characteristics include high explosive energy, sustained mechanical performance, and favorable model specifications. By continuously optimizing propellant formulations and design directions, improvements in combustion catalysts have significantly enhanced the energy release and prolongation properties of these propellants. This ensures the safety, reliability, and sustained performance of solid rocket propellants. Research currently emphasizes enhancing energy levels and the longevity of explosions [6,7,8,9].

Under catalytic oxidation by oxidizers, solid propellants undergo intense combustion, emitting light and heat, and producing a large volume of gases that result in high-energy thrust [10,11]. Burn rate is a crucial indicator of solid propellants, mainly influenced by the contact area and catalytic effects of the oxidizers and catalysts [12]. The energy release, burn rate, and combustion pressure index of solid propellants are vital for their application, particularly for solid missiles, rockets, and ballistic control [13]. Thus, it is essential to reduce combustion pressure while increasing thrust and burn rate, which has become a major research focus for various institutions and rocket research centers [14].

The performance of burn rate catalysts significantly affects the propulsion systems of solid propellants. Key evaluation criteria for these catalysts include burn rate and pressure index [15,16]. Researchers aim to develop catalysts with a wider adjustable burn rate range and lower pressure index. Current research on combustion catalysts primarily involves metal–organic compounds, metals and metal oxides, composite metal oxides, and novel carbon materials [17]. Metal–organic compounds, which are organic salts and complexes without amino nitro groups, can generate numerous active sites during reactions, thus promoting rapid combustion of solid propellants. However, due to their toxic components and pollutant production, developing green and efficient catalysts is a future direction [18]. Metals and metal oxides offer advantages such as stable physicochemical properties, simple preparation, and low cost. Composite metal oxides, composed of various oxides and metals, exhibit superior thermal resistance, chemical stability, and hardness compared to single metals or metal oxides [19]. Novel carbon materials have large specific surface areas, good thermal conductivity, and combustion properties, and can be combined with other metallic and non-metallic materials to enhance catalytic capabilities and effects. The synergy of various materials can significantly improve performance and catalytic capacity [20].

Currently, the most widely used and mature catalytic systems in modified composite materials includee Pb, Cu, and carbon composites [21]. Carbon black, commonly used in rubber and ink industries for its coloring and reinforcing properties, is an amorphous carbon present in powder form, aggregated into chains or spherical clusters with a diameter of 2–3 nm. It can adsorb, decompose, and catalyze metal ions, reducing catalyst agglomeration and improving catalytic efficiency [22].

This study successfully synthesized a copper atom catalyst anchored on a carbon black support by complexing metal cations with 1,10-phenanthroline, followed by adsorption of the resulting metal complex onto the carbon black and pyrolysis under an argon atmosphere at 600°C. Characterization and analysis of the catalysts were conducted using scanning electron microscope (SEM), transmission electron microscope (TEM), X-ray diffractometer (XRD), X-ray photoelectron spectrometer (XPS), and X-ray absorption fine structure spectrometer (XAFS). High-temperature pyrolysis experiments and catalytic oxidative decomposition kinetics were used to study energetic materials such as 2,4,6,8,10,12-hexanitrohexaazaisowurtzitane (CL-20), 1,1-diamino-2,2-dinitroethylene (FOX-7), HMX, and AP. Differential thermal analysis and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) were employed to investigate the catalysts’ effects on propellant combustion performance, providing theoretical and data support for subsequent propellant research.

All chemicals used were of analytical grade, including copper acetate monohydrate [Cu(CH3COO)3·H2O], 1,10-phenanthroline (C12H8N2·H2O), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), carbon black, and argon gas.

Magnetic stirrer (IKA-90), high-temperature tube furnace (BR-12NT-40/300), electric thermostatic blowing drying oven (DCTG-9205A), SEM (Axia ChemiSEM), TEM (Spectra 300 TEM), XAFS (XAFS300, USA), XPS (Thermo Scientific ESCALAB 250Xi), XRD (ARL EQUINOX 3000), and Solid-phase in situ thermal infrared detector (Thermolysis/RSFTIR) were used in this study.

A total of 20 mL of DMSO was measured using a graduated cylinder and added to a 250 mL beaker. Copper acetate monohydrate (99.83 mg) and 1,10-phenanthroline monohydrate (297.33 mg) were weighed and then added to the beaker. The beaker was placed on a magnetic stirrer, and the stirring speed was set to 1,000 rpm. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 20 min. Carbon black (696 mg) was weighed and slowly added to the solution. The oil bath was heated to 60°C, and the reaction was allowed to proceed for 4 h. The resulting mixture was filtered, and the solid substance was dried in a thermostatic drying oven at 190°C for 12 h to obtain a black solid precursor.

The black precursor was ground to a particle size of 200 mesh and transferred to a ceramic crucible. The crucible was placed in a high-temperature tube furnace, and under argon protection, the furnace was heated to 600°C at a rate of 3°C/min and maintained at this temperature for 2 h. After cooling to room temperature, the resulting product was identified as the combustion rate catalyst, denoted as CB@Cu.

The structure and composition of CB@Cu were characterized using XRD, with measurements performed using a Cu Kα source over a 2θ range of 20°–70° and a scanning rate of 8°/min. The morphology and size of CB@Cu were examined using SEM (Axia ChemiSEM) at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. TEM (Spectra 300) was conducted at an accelerating voltage of 300 kV. The valence states of elements in the CB@Cu complex were analyzed using XPS. The effects of the CB@Cu catalyst on the thermal decomposition of AP, CL-20, FOX-7, and HMX (with a mass ratio of AP, FOX-7, CL-20, and HMX to CB@Cu of 95:5) were investigated using a solid-phase in situ thermal infrared detector (Thermolysis/RSFTIR). Each sample was heated at rates of 5, 10, 15, and 20°C/min under an N2 flow rate of 50 mL/min, using sample masses of 0.4 ± 0.2 mg. The properties and catalytic performance of the substances before and after mixing were analyzed by thermogravimetric-mass spectrometry.

Figures 1 and 2 show the morphology of the catalyst using SEM and TEM. Figure 1a and b are appearance images of 100 nm and 1 μm catalysts, respectively. The CB@Cu catalyst exhibits agglomeration and has a flat strip-like structure on the surface. The reason is speculated to be closely related to the van der Waals force between molecules and the mutual influence of oxygen-containing functional groups. The agglomeration phenomenon in Figure 1b is due to the large number of flaky particles forming a clustered aggregate due to functional groups and intermolecular forces. Figure 1c is an image of the appearance scan of Cu in the catalyst. It can be seen from the figure that there is also an agglomeration phenomenon in this shape, and there is a spherical particle distribution on the surface.

SEM images of CB@Cu and Cu: (a) CB@Cu 100 nm, (b) CB@Cu 1 μm, and (c) Cu 1 μm.

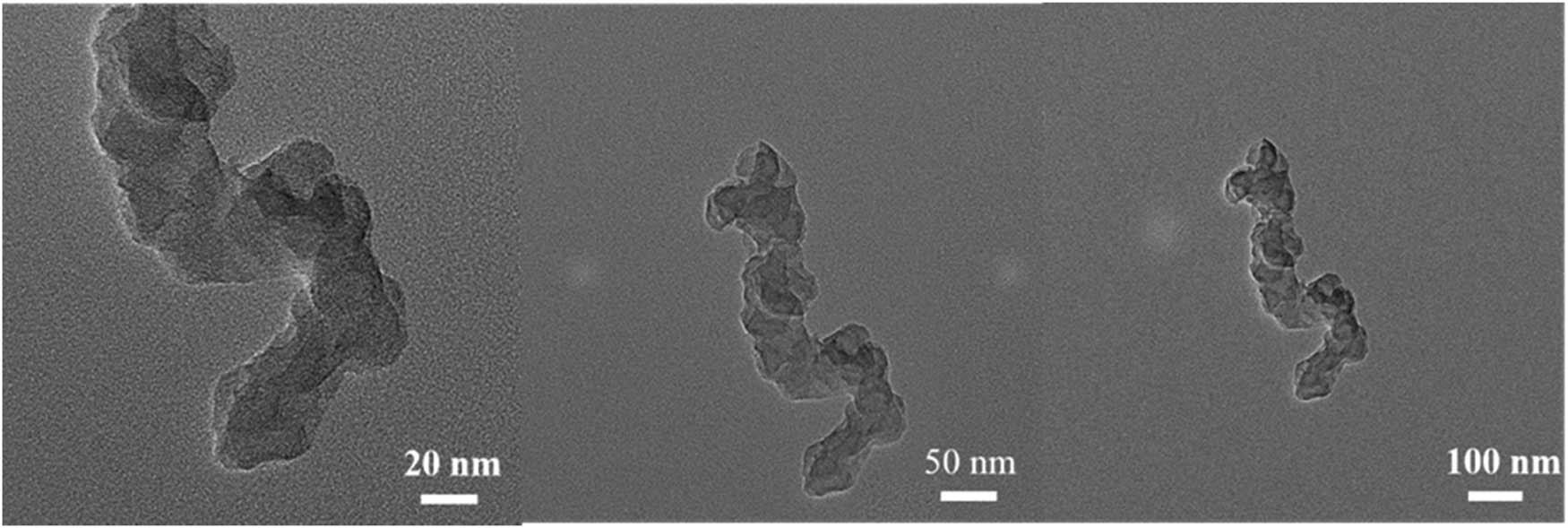

TEM of CB@Cu.

Scanning image of the catalyst using a TEM is shown in Figure 2. Catalyst morphologies with sizes of 20, 50, and 100 nm were presented, respectively. It can be seen that the average size of the catalyst particles is 20–40 nm, indicating that they are smooth without edges and present a stacked shape.

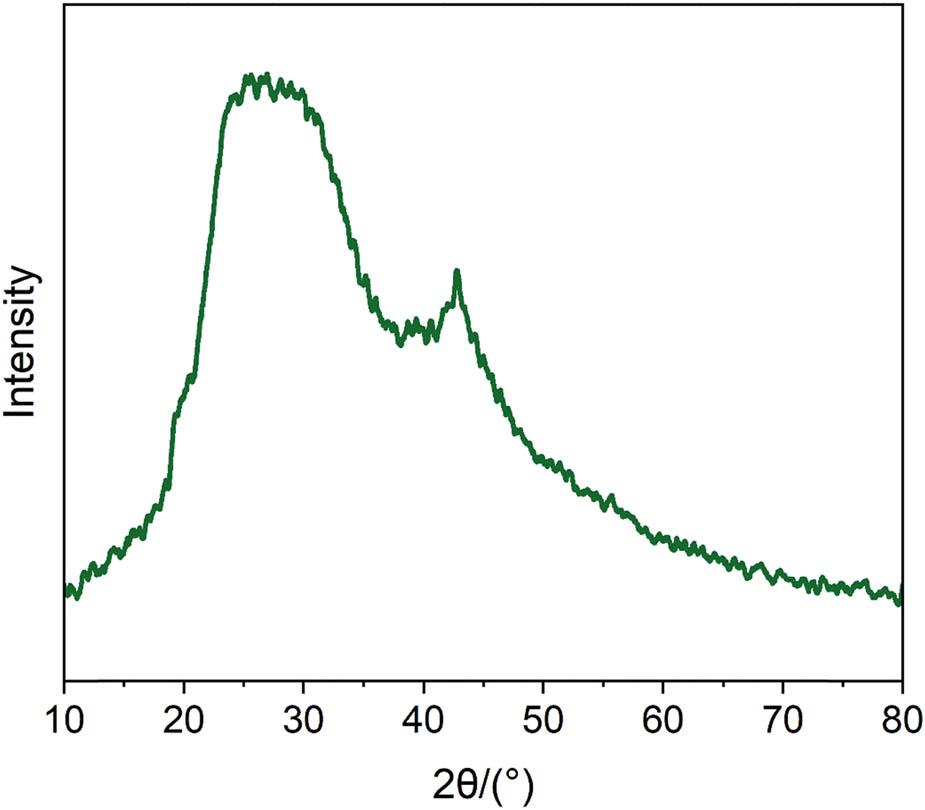

By performing XRD analysis on the synthesized catalyst sample, the characterization results are shown in Figure 3. The diffraction peaks corresponding to the catalyst samples appear at 2θ positions of 25° and 42.5°, respectively. These two diffraction peaks correspond to the crystal plane index [23] (111) and (221) of the cubic structural metallic copper, indicating that the catalyst contains copper crystalline material.

XRD spectrum of catalyst CB@Cu.

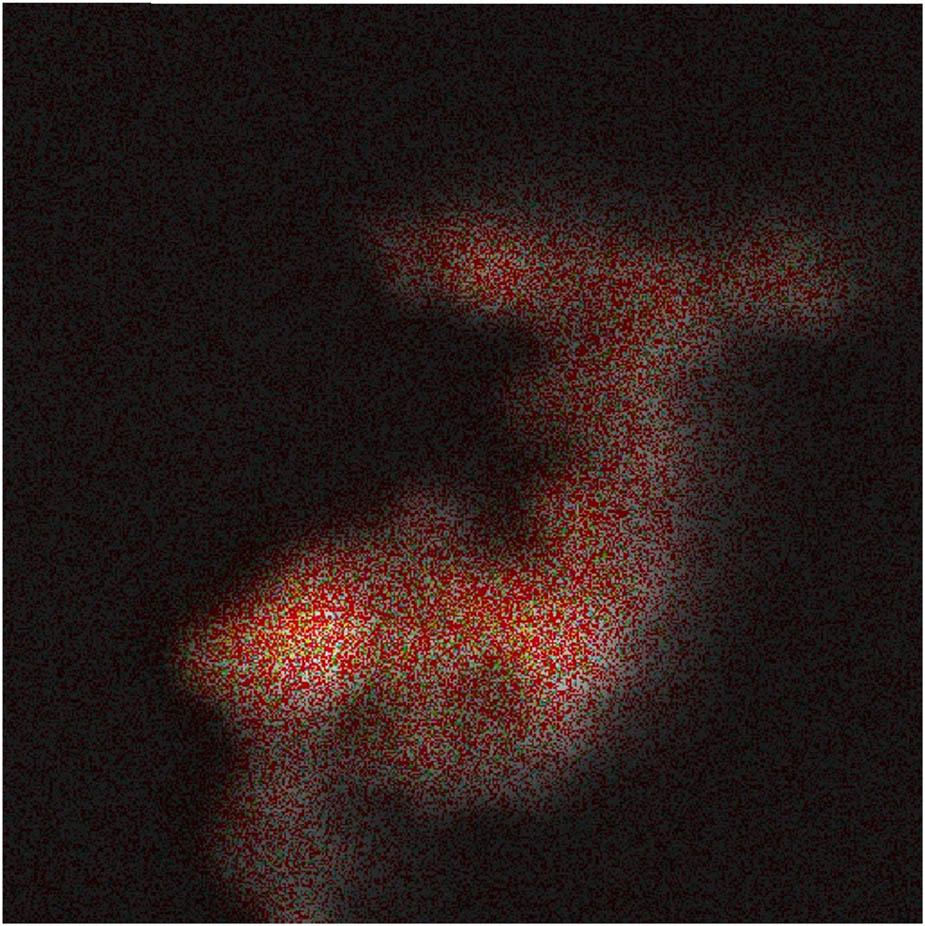

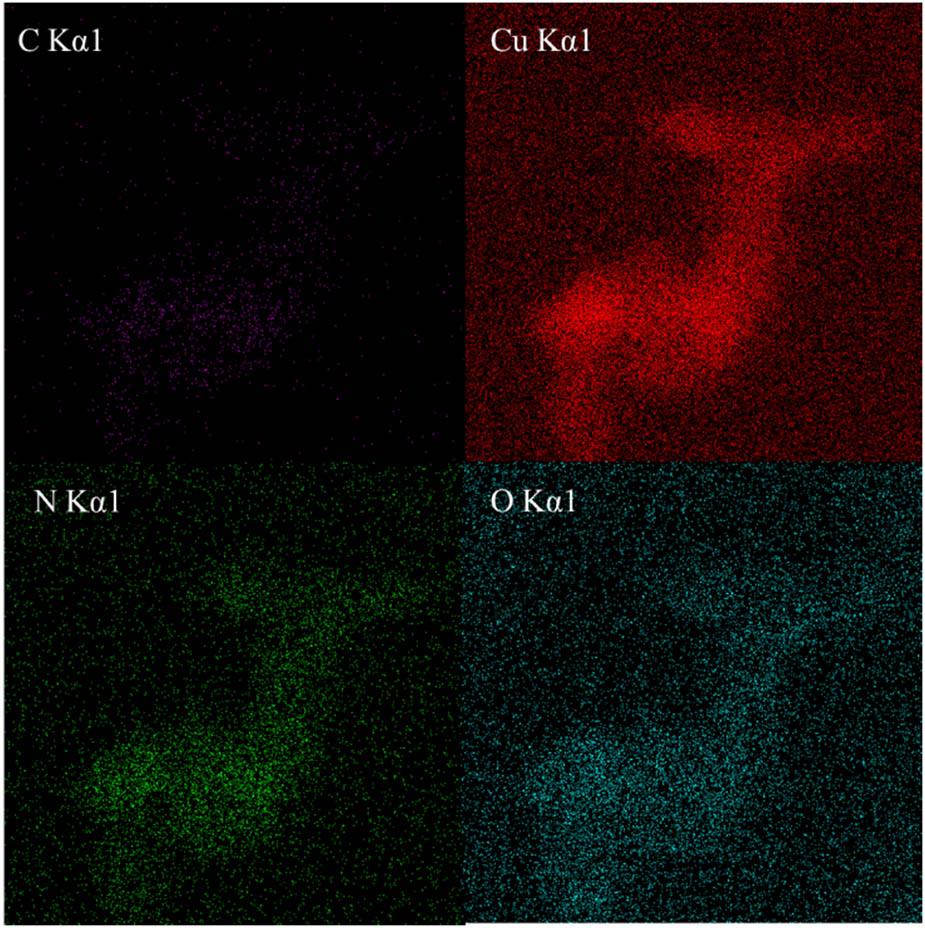

The EDS characterization results of the catalyst CB@Cu are shown in Figures 4 and 5. Figure 4 is the distribution overlay diagram of the four elements C, N, O, and Cu. Figure 5 is the individual standard result diagram of the four elements. It can be seen from the figure that the content of Cu is the largest and the distribution is relatively uniform. The contents of O and N are less than Cu and the distribution is uneven. The Cu content of the CB@Cu catalyst is 58.76%, the O content is 26.32%, the N content is 13.23%, and the C content is 1.78%.

C, N, O, and Cu elements distribution diagram.

Distribution diagram of the four elements.

An X-ray photoelectron spectrometer was used for analysis to obtain the chemical composition of the elements in the sample and the valence distribution information of the elements. As can be seen in Figure 6, the catalyst CB@Cu completely contains four elements: C, N, O, and Cu, and does not contain other impurity elements. The Gaussian method was used for fitting. It was found in the O 1s spectrum in Figure 7a that there are two obvious absorption peaks, corresponding to the binding energies of 531.8 and 529.4 eV, respectively, and the corresponding functional groups are C–O and M–O. In the C 1s spectrum in Figure 7b, there are two significant absorption peaks, which are the C═N and C–C or C═C functional groups formed during the synthesis process. The binding energies are 285.4 and 284.8 eV, respectively. The two peaks fit into the main absorption peak of C. In the N 1s spectrum of Figure 7c, oxidized nitrogen, pyrrole nitrogen, pyridine nitrogen, and Cu–N bonds appear. These absorption peaks are fitted into the N 1s spectrum. In the Cu 2p spectrum in Figure 7d, there is spin coupling of Cu’s 2p orbital electrons at positions 958.7, 952.3, 935.2, and 931.8 eV, corresponding to Cu 2p5/2, Cu 2p1/2, Cu 2p3/2, and Cu 2p3/2. The typical binding energy of Cu in the 2p3/2 orbit also contains a satellite peak of divalent copper ions at 944.4 eV. The results are consistent with the XRD analysis, indicating that the new catalyst containing Cu was successfully prepared.

XPS spectrum of catalyst CB@Cu.

High-resolution XPS spectra of (a) O 1 s, (b) C 1 s, (C) N 1 s, and (d) Cu 2p of catalyst CB@Cu.

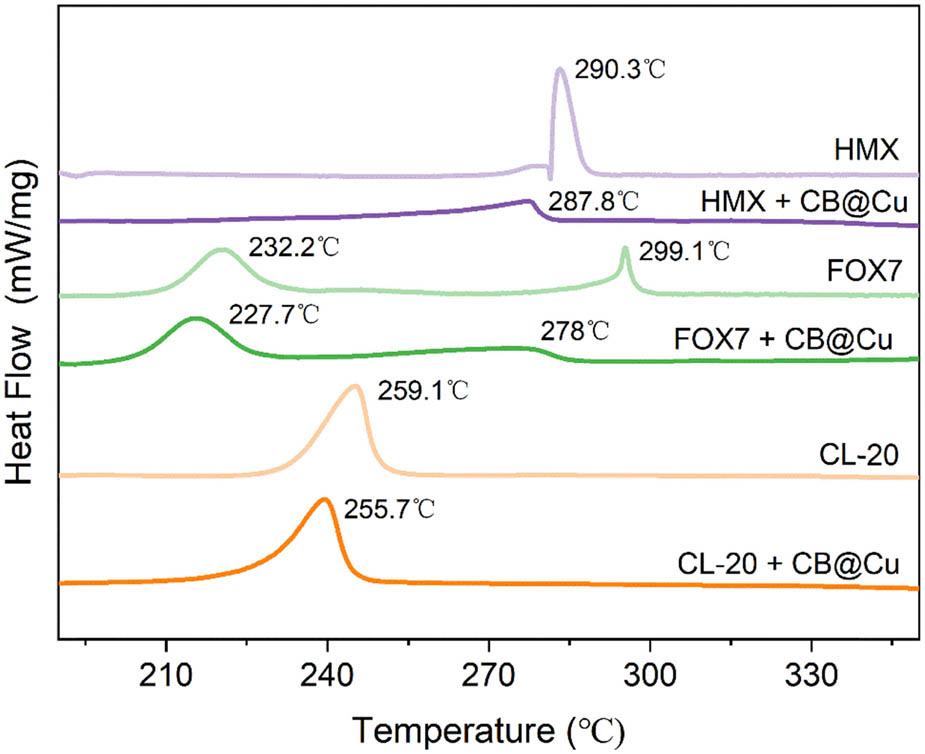

Under N gas atmosphere, weigh 0.4 mg of the catalyst sample and put it into an Al2O3 crucible, and then add 8 mg each of CL-20, FOX-7, and HMX, respectively, to make the catalyst content account for 5%. At a heating rate of 20°C/min, the pyrolysis effects of CL-20, FOX-7, HMX energetic materials, and materials containing 5% catalyst were studied in the temperature range of 50–350°C. The results are shown in Figure 8. In the temperature range of 200–330°C, the energetic materials HMX and CL-20 have an exothermic wind peak, and the exothermic temperatures are 290.3 and 259.1°C, respectively. The energetic material FOX-7 has two exothermic peaks, with exothermic temperatures of 232.2 and 299.1°C. After adding the new catalyst, the exothermic temperatures of energetic materials are 255.7°C for CL-20, 287.8°C for HMX, and 227.7 and 278°C for FOX-7. After adding the catalyst CB@Cu, the endothermic peaks of the three energetic materials moved toward low temperature, but the amplitude of the movement was small. The maximum thermal decomposition temperature is 3–5°C, which is lower than that before adding the catalyst. At lower temperatures, the catalyst has a better catalytic effect on energetic materials. The catalyst shows the formation of electron transfer and the presence of metallic Cu ligands, increasing the number of active sites with energetic materials, making the heat release of energetic materials more concentrated, and increasing the degree of thermal decomposition.

DSC pyrolysis curve of catalyst mixed energetic materials.

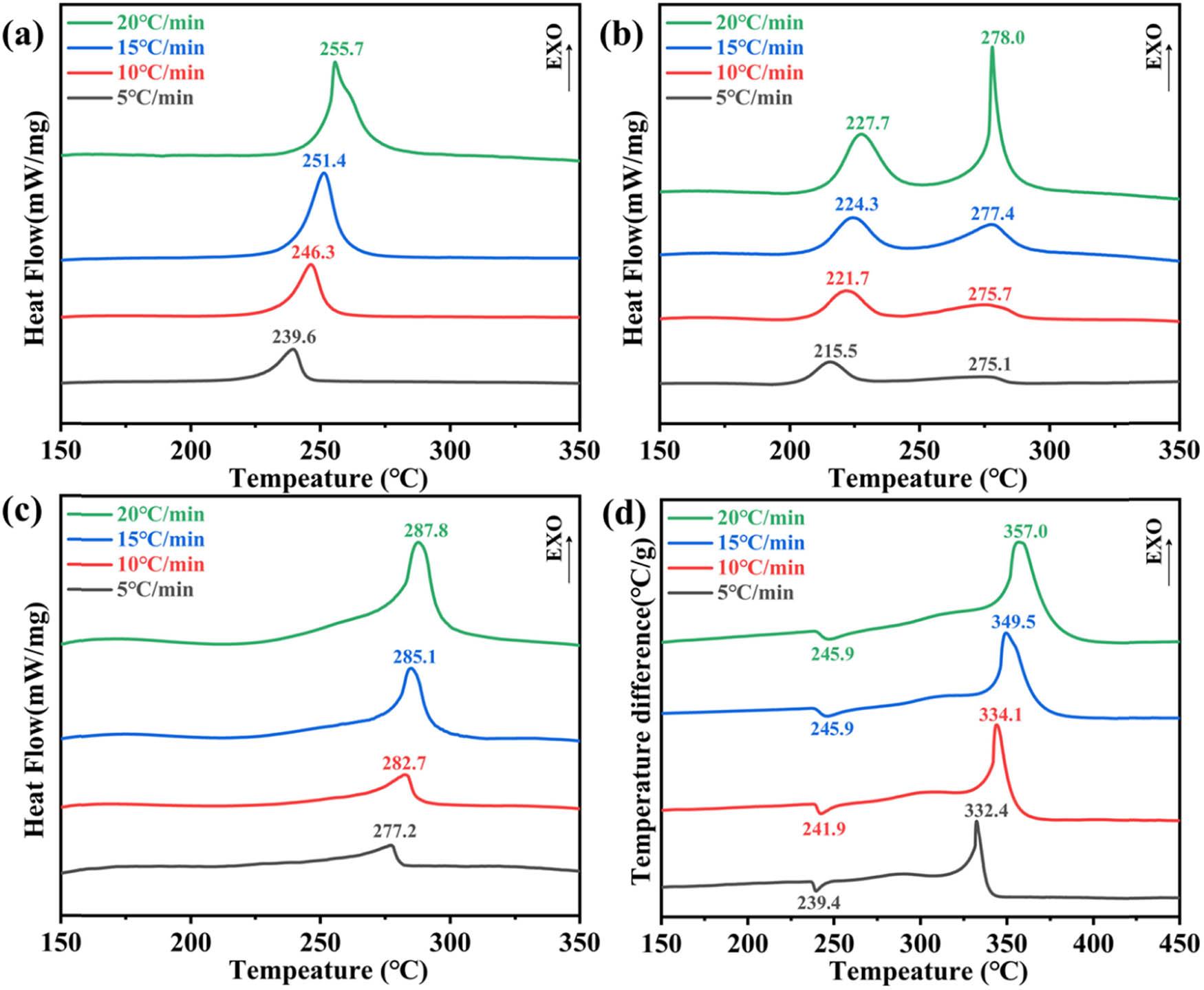

Under N gas atmosphere, 0.4 mg of catalyst sample was weighed and placed in an Al2O3 crucible, and then 8 mg of CL-20, FOX-7, and HMX were added, respectively, and the catalyst content accounted for 5%. The pyrolysis effects of CL-20, FOX-7, HMX energetic materials, and the materials with 5% catalyst added at a temperature range of 50–350°C were studied at a heating rate of 5, 10, 15, and 20°C/min. Under Ar gas atmosphere, 2 mg of catalyst sample was weighed and placed in an Al2O3 crucible, and then 8 mg of AP energetic material was added, respectively, and the catalyst content accounted for 5%. The pyrolysis effects of AP energetic material and the materials with 5% catalyst added at a temperature range of 150–450°C were studied at a heating rate of 5, 10, 15, and 20°C/min. The experimental results are shown in Figure 9. It can be seen that the decomposition peaks of CL-20-CuCBx, FOX-7-CuCBx, HMX-CuCBx, and AP-CuCBx move to the right with increasing heating rate. In Figure 9b, the decomposition of FOX has two stages. At a heating rate of 20°C/min, the endothermic peak of the crystal transformation begins at 227.7°C. FOX changes from the orthorhombic crystal system to the cubic crystal system. When it reaches the low-temperature exothermic peak, FOX partially decomposes and produces intermediate products. When reaching the high-temperature decomposition peak, FOX is completely decomposed, generating volatile products. As the heating rate increases, the decomposition temperature of the second stage gradually increases, and the decomposition rate of FOX gradually accelerates.

DSC curves of energetic material catalysts at different heating rates: (a) CL-20CuCBx, (b) FOX-7-CuCBx, (c) HMX-CuCBx, and (d) AP-CuCBx.

The Kissinger method is used to linearly fit the heating rate and the maximum catalytic oxidation temperature. The slope is −E k/R and the intercept is Ln(AR/E k). From the above relationship, the activation energy and pre-exponential factor can be obtained. It can be seen from Table 1 that the activation energy E k of energetic materials with catalyst added is significantly lower than that of energetic materials without catalyst, which advances the decomposition temperature of energetic materials. The activation energy is reduced by 31.39, 43.43, 180.46, and 10.08 kJ/mol, respectively. From the experimental results and catalytic oxidation thermal analysis and kinetic analysis, the catalyst CB@Cu has a significant catalytic effect on energetic materials CL-20, FOX-7, HMX, and AP.

Kinetic parameters of energetic material catalysts.

| Energetic material catalysts | β/(°C/min) | Kinetic calculation parameters | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | Kissinger’s method | ||

| E k (kJ/mol) | R | |||||

| CL20-CuCBx | 512.75 | 519.45 | 524.55 | 528.85 | 203.37 | 0.9565 |

| FOX-7-CuCBx | 548.25 | 548.85 | 550.55 | 551.15 | 1012.96 | 0.9887 |

| HMX-CuCBx | 550.35 | 555.85 | 558.25 | 560.95 | 350.42 | 0.9563 |

| AP-CuCBx | 569.55 | 571.25 | 586.65 | 594.15 | 118.54 | 0.8955 |

| CL-20 | 518.35 | 526.25 | 529.85 | 532.25 | 234.76 | 0.9968 |

| FOX-7 | 568.55 | 571.05 | 571.25 | 572.25 | 1056.39 | 0.972 |

| HMX | 556.45 | 559.85 | 561.75 | 563.45 | 530.88 | 0.0004 |

| AP | 551.65 | 566.95 | 576.85 | 582.25 | 128.62 | 0.9993 |

The process of breaking the N–N structure in CL-20 forms an obstacle to the entire activation. The decomposition of the catalyst produces copper metal oxides, which accelerate the oxidation of free radicals and produce a large amount of nitrogen oxides [24]. Compared with CL-20 without catalyst, the pyrolysis of the catalyst inhibits the breakage of the structural functional groups of CL-20, making it easier to obtain electrons. The high-temperature pyrolysis process of FOX-7 mainly includes phase changes, low-temperature pyrolysis process, and high-temperature pyrolysis process. Low-temperature pyrolysis produces nitrogen oxides, and high-temperature pyrolysis produces ammonia-containing compounds. The catalytic effect of the catalyst occurs in the high-temperature pyrolysis stage of FOX-7. Therefore, the catalyst greatly promotes the high-temperature pyrolysis of FOX-7.

-

(1)

In this study, a CB@Cu catalyst was successfully prepared using a hydrothermal synthesis method, and CL-20, FOX-7, HMX, and AP energetic materials were studied and analyzed using a high-temperature pyrolysis process and catalytic oxidation thermal decomposition kinetic analysis. The catalyst CB@Cu significantly reduces the activation energy during the pyrolysis process of energetic materials, advances the decomposition temperature of energetic materials, and has a significant catalytic effect.

-

(2)

After adding the catalyst CB@Cu, the endothermic peaks of the three energetic materials move toward low temperature, but the amplitude of the movement is small. The maximum thermal decomposition temperature is 3–5°C lower than before adding the catalyst. At lower temperatures, the catalyst has a better catalytic effect on energetic materials. The catalyst shows the formation of electron transfer and the presence of metallic Cu ligands, increasing the number of active sites with energetic materials, making the heat release of energetic materials more concentrated, and increasing the degree of thermal decomposition.

-

(3)

Compared with pure AP, CL-20, FOX-7, and HMX energetic materials, adding the catalyst CB@Cu significantly reduces the high-temperature decomposition temperature of the four energetic materials and promotes the oxidative decomposition efficiency.

-

(4)

Cu element belongs to transition metals, with a special structure and good metal thermal conductivity. Its surface has a large number of lattice defects and a relatively uniform distribution of elements, making it easy to absorb substances containing excess electrons and form stable complex structures. Catalyzer CB@Cu containing metal Cu and carbon black enables Cu to form a complex with DMSO. In addition, carbon black materials have the characteristics of small particle size and large specific surface area, which can accumulate more heat in a short period of time, thereby accelerating the thermal decomposition of energetic materials. Due to the above reasons, the catalyst CB@Cu reduced the decomposition temperature and activation energy of energetic materials.

Yajing Yao: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Original Draft, Visualization. Shuangqi Hu: Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing, Project Administration.

Authors state no conflict of interest.