The concrete industry will face significant challenges in response to the net zero carbon emissions demand by 2050 [1]. The ready-mix concrete industries are also an urgent target for industrial upgrading in this campaign [2]. The amount of cement used in the concrete industry significantly increased carbon dioxide emissions, with 0.8 metric tons of carbon dioxide derived from each metric ton of cement used [3]. Therefore, the Paris Agreement on Climate Change states that the cement and concrete industries should reduce their annual CO2 emissions by at least 16% by 2030 [4]. In the last few decades, ready-mix concrete plants have been using one or more supplementary cementitious materials in replacement of cement, such as fly ash, ground-granulated blast-furnace slag (GGBS), silica fume, etc., which not only help to reduce CO2 emissions but also help to improve workability [5], mechanical properties [6], and durability [7]. These materials are also cost-effective and can help reduce the cost of construction. Additionally, their use can also help reduce the need for additional cement production, which is beneficial for the environment. Thus, these materials can be an attractive option for the construction industry.

The addition of fine particles of supplementary cementitious materials to concrete contributed to an increase in the bulk density of the mixture. It improved the strength and durability of the concrete [8]. The fine particles also reduced the permeability of the concrete in the mix. It also reduced the amount of cement used in the mix, resulting in a more sustainable [9] and environmentally friendly product [10]. However, it was very difficult for these fine particles to be uniformly dispersed in concrete during the premixing process of conventional concrete. As the smallest size particles cannot effectively enter the interfacial transition zone, it results in dispersed agglomeration in concrete. This led to the poor performance of materials [11]. To overcome these limitations, researchers have developed new technologies that accurately control fine particle dispersion in concrete [12]. These technologies included surfactants, cement additives, and other methods. In fact, ready-mix plants still needed to increase the amount of chemical additives or use high-efficiency water-reducing additives to improve the uniformity of concrete, which also led to higher material costs.

The dry mixing techniques promoted uniformity in the proportion of the binders. The dry mixing techniques were also effective in reducing the cost of production as there was no need for costly mixing equipment and labor. Furthermore, the dry mixing techniques made it easier to control the moisture content of the binders, which was essential for ensuring the quality of the product. Premixing the binders through the machine provided a more uniform proportion of binders, allowing them to utilize their properties more efficiently. In the construction industry, such premixed technology has been widely used in dry-mix mortars. It provided a standardized procedure [13] for concrete mixing plants, which helped to improve the uniformity of concrete [14]. This standardization allowed for more accurate and consistent construction, resulting in better-quality structures. Additionally, the premixed technology reduced the cost of concrete production, making it more cost-effective. The premixed technology enhanced the homogeneity of the binders by thoroughly blending the cement with supplementary cementitious materials, improving particle dispersion and reducing blockages. Concrete production improved productivity and plant efficiency. It met stringent quality standards, effectively reduced dust emissions during the mixing process, and improved the flexibility of mix design [15].

In a ready-mix concrete plant, supplementary cementitious materials were placed in large mixing drums with cement during the concrete production process. To improve the workability or related properties of the concrete, additional chemical admixtures were required, which increased the cost of the concrete. Alternative methods of incorporating these materials into concrete were investigated to reduce these costs. One of these methods was to add these materials to the concrete during the batching process instead of during the mixing process. In practice, binders were often stored in the wrong storage silos at concrete plants, resulting in incorrect mixing proportions. Operators also needed to increase manpower for quality control operations, which can be improved with premixed blended cement. It proved more cost-effective and efficient. Thus, this innovative technique proved to be an effective way of reducing the cost of the concrete while maintaining its quality. This study used a dry mixing technique to premixed binders (including cement, fly ash, and furnace stone) to produce premixed blended cement, which was categorized as complying with the CNS 15286 Specification in Taiwan – Blended hydraulic cement [16]. Under specific engineering requirements, the differences in performance between this type of blended cement and the general type of concrete with supplementary cementing materials were compared using engineering properties such as workability, compressive strength, heat of hydration, and the chloride ion diffusion coefficient. This study also compared the economics and carbon footprint of the two types of mixtures to illustrate the market potential and application value of blended cement. This study also focused on verifying the suitability and effectiveness of premixed blended hydraulic cement.

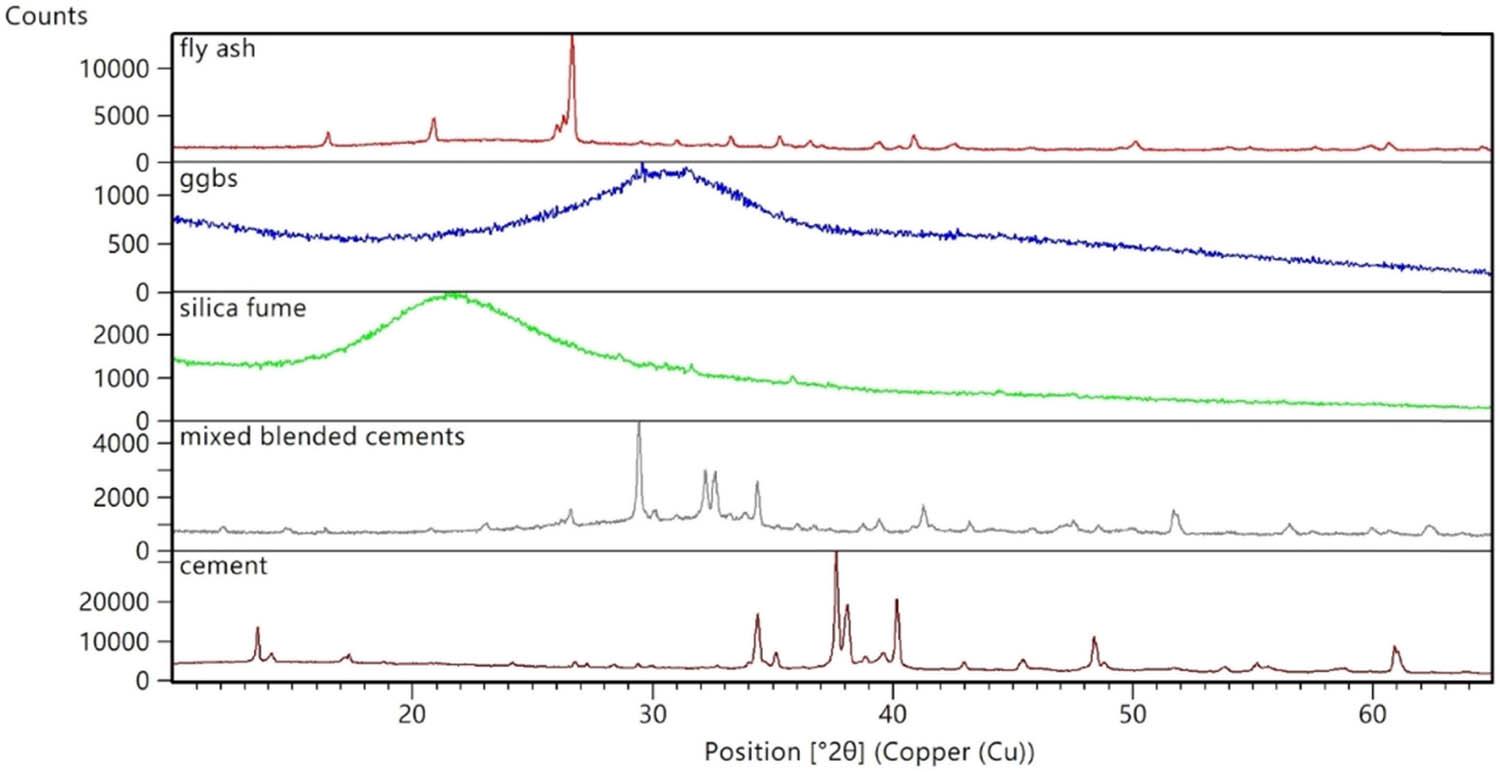

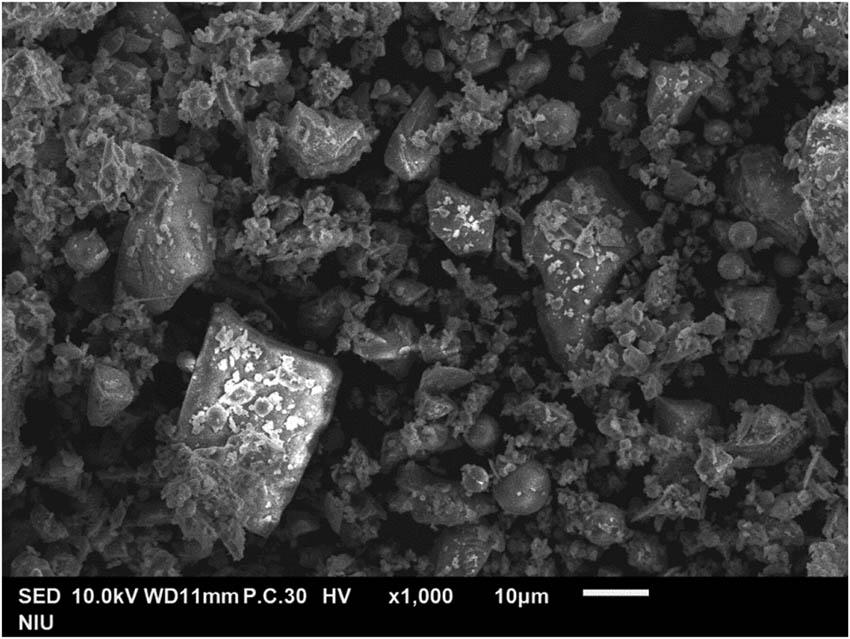

Five types of cementitious materials were used in this study, including Portland Type I cement, fly ash, GGBS, silica fume, and blended cement. The cement was Portland Type I cement produced by Advanced-Tek System Company in Taiwan, which met the requirements of ASTM C150, with a specific surface area of 3,950 cm2/g and a specific gravity of 3.15. GGBS was sourced from Advanced-Tek System Company in Taiwan and had a specific surface area of 5,840 cm2/g, a specific gravity of 2.90, and an activity strength index of 144% at 28 days. Fly ash was sourced from the Lin Kou Thermal Power Plant in Taiwan and had a specific surface area of 10,800 cm2/g, a specific gravity of 2.41, and an activity strength index of 88% at 28 days. Silica fume was obtained from Microsilica Grade 940, produced by Elkem in Norway. The main ingredient is highly reactive volcanic ash with more than 90% silica oxide content and a specific gravity of 2.20. It was distributed by Poplar Industrial Company Limited in Taiwan. Silica fume had a specific surface area of 220,000 cm2/g and an activity strength index of 112% at 28 days. The blended cement was developed and manufactured by Yi-Xing Ready Mixed Concrete Co., Ltd. in Taiwan. It primarily consisted of cement, GGBS, and fly ash premixed in a dry mixer (proportions cannot be provided as they are commercially confidential cement mixes) as Type IP blended cement. Blended cement was then used to produce concrete, proving more efficient and cost-effective than conventional cement products. It also improved strength and durability. The blended cement contained the same materials as previously described. It had a specific gravity of 2.71, a specific surface area of 4,880 cm2/g, and a 28-day activity strength index of 110%. The chemical compositions of these four binders are given in Table 1, and the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns are shown in Figure 1. The coarse and fine aggregates used in this study were obtained from the Lanyang River in Taiwan. The basic properties of the coarse aggregates are given in Table 2. The fineness modulus of the fine aggregates was 2.95, the water absorption was 1.70%, the surface moisture content was 1.20%, and the specific gravity was 2.62. The superplasticizer was a carboxylic acid high-performance water-reducing agent (Sikament®-1250) produced by Sika Corporation in Taiwan. The scanning electron microscopy (SEM) photograph of blended cement is shown in Figure 2, where the spherical particles were fly ash.

Chemical compositions of the binders.

| Materials | Chemical composition (%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CaO | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | MgO | SO3 | K2O | Na2O | P2O5 | Others | |

| Cement | 62.59 | 21.24 | 4.78 | 3.27 | 2.53 | 2.27 | 0.45 | 0.38 | — | 2.49 |

| Fly ash | 4.80 | 48.60 | 34.31 | 6.46 | 1.04 | 0.71 | 1.21 | 0.75 | 0.58 | 1.54 |

| GGBS | 44.68 | 24.85 | 20.49 | 0.67 | 5.43 | 1.79 | 0.33 | 0.22 | 0.03 | 1.51 |

| Silica fume | 1.35 | 94.40 | 0.53 | 0.14 | 0.48 | 1.02 | 1.59 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.23 |

| Blended cement | 51.26 | 21.10 | 16.98 | 3.27 | 3.01 | 2.23 | 0.57 | 0.33 | 0.19 | 1.06 |

XRD patterns of the binders.

Basic properties of coarse aggregates.

| Sieve no. | Maximum particle size = 19 mm | Maximum particle size = 9.5 mm | Maximum particle size = 1.6 mm | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Remain weight (g) | Retention (%) | Sieving rate (%) | Remain weight (g) | Retention (%) | Sieving rate (%) | Remain weight (g) | Retention (%) | Sieving rate (%) | |

| 3/2″ | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| 1″ | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| 3/4″ | 348 | 4 | 96 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| 1/2″ | 6,911 | 75 | 25 | 1,022 | 18 | 82 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| 3/8″ | 8,441 | 92 | 8 | 2,641 | 47 | 53 | 11 | 0 | 100 |

| #4 | 9,109 | 99 | 1 | 5,228 | 93 | 7 | 2,815 | 57 | 43 |

| #8 | 9,140 | 100 | 0 | 5,545 | 99 | 1 | 4,636 | 93 | 7 |

| Bottom | 9,176 | 100 | 0 | 5,615 | 100 | 0 | 4,975 | 100 | 0 |

| Physical properties | |||||||||

| Moisture content (%) | 0.89 | 1.17 | 2.23 | ||||||

| Absorption (%) | 0.83 | 1.25 | 1.13 | ||||||

| Surface moisture content (%) | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1.1 | ||||||

SEM photograph of blended cement.

The concrete used in this study was mixed in a ready-mix concrete plant with a volume of 3 m3 for each proportion, from which specimens were taken at the end of the mixing process for subsequent related tests. The specimens were then subjected to curing and testing in a laboratory environment. Two groups of binders with water–binder ratios (w/b) of 0.32 and 0.39 were selected for the test. After setting the benchmark group (mix nos A1 and B1, cement replacement of 50%), three binders with different proportions were used for comparison and verification. The percentages of binders for the eight sets of proportions are given in Table 3. The concrete proportions are given in Table 4. The concrete mix is based on the three grades of coarse aggregates in Table 2, with a fixed proportion of 45, 45, and 10% for particle sizes of 19, 9.5, and 1.6 mm. The tests included slump-flow, compressive strength, hydration heat, and chloride ion diffusion tests. The results were then used to determine the performance of the concrete. Therefore, verifying the applicability of different proportions in real construction cases is necessary. It can be used as a referential basis for decision-making analysis of ready-mix concrete plants.

Mix percentage of binders.

| Mix no. | w/b | Binders | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cement (%) | GGBS (%) | Fly ash (%) | Silica fume (%) | Blended cement (%) | ||

| A1 | 0.32 | 50 | 35 | 15 | ||

| A2 | 100 | |||||

| A3 | 45 | 30 | 20 | 5 | ||

| A4 | 35 | 35 | 30 | |||

| B1 | 0.39 | 50 | 35 | 15 | ||

| B2 | 100 | |||||

| B3 | 45 | 30 | 20 | 5 | ||

| B4 | 35 | 35 | 30 | |||

Mix proportions (kg/m3).

| Mix no. | Water | w/b | Binders | Aggregates | Superplasticizer | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cement | GGBS | Fly ash | Silica fume | Blended cement | Coarse aggregates | Fine aggregates | ||||

| A1 | 202 | 0.32 | 330 | 231 | 99 | — | — | 926 | 552 | 5.61 |

| A2 | 144 | — | — | — | — | 467 | 985 | 786 | 5.65 | |

| A3 | 199 | 297 | 198 | 132 | 33 | — | 933 | 533 | 5.81 | |

| A4 | 202 | 231 | 231 | 198 | — | — | 965 | 483 | 5.28 | |

| B1 | 188 | 0.39 | 247.5 | 173.3 | 74.3 | — | — | 939 | 733 | 3.96 |

| B2 | 159 | — | — | — | — | 420 | 947 | 837 | 5.29 | |

| B3 | 185 | 222.8 | 148.5 | 99 | 24.8 | — | 943 | 730 | 4.16 | |

| B4 | 184 | 175 | 175 | 150 | — | — | 938 | 702 | 4.25 | |

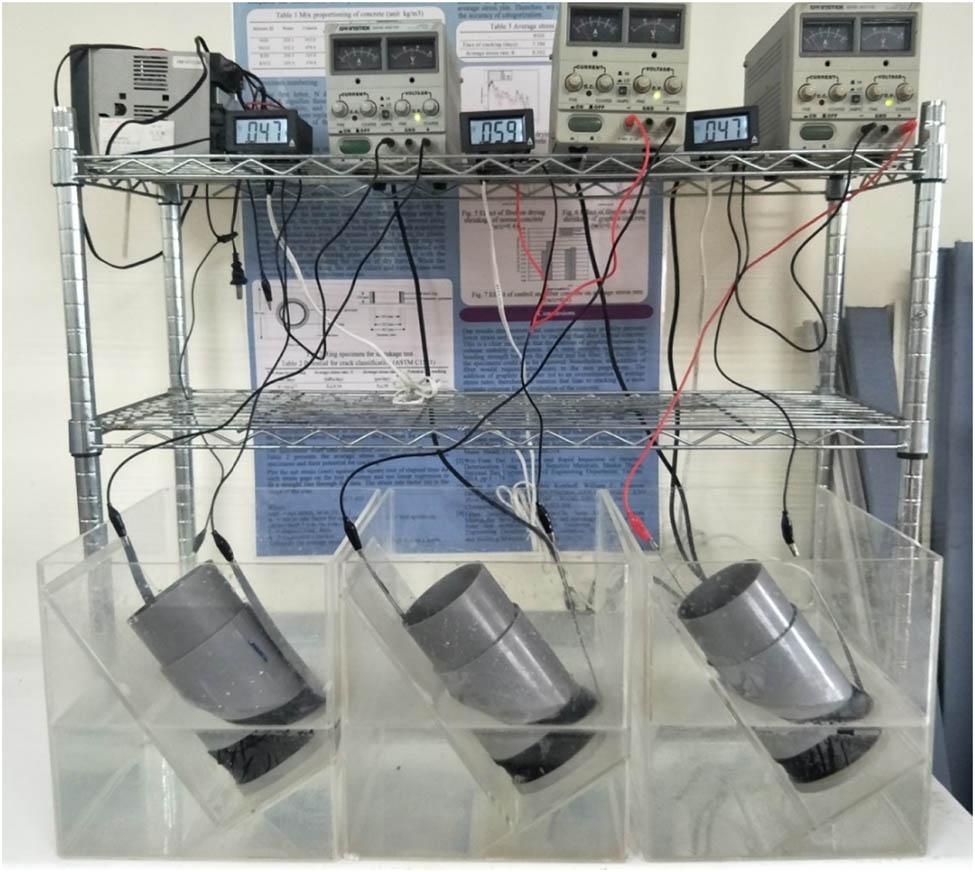

To facilitate the application of concrete to actual construction, the concrete proportion was designed as self-consolidating concrete. The slump and flow test was conducted according to ASTM C1611, and the designed slump flow was 60–70 cm. The compressive strength test was performed on cylindrical specimens with a size of ϕ10 × 20 cm. The reference specification for this test was ASTM C39, with test ages of 7, 28, and 56 days. The compressive strength test was conducted using a 200 ton MTS Compression Machine. The results were recorded and compared to the reference specification. The non-steady-state chloride ion diffusion coefficient was calculated using Fick’s second law after a rapid chloride migration test using the NT Build 492 specification. The test was performed on cylindrical specimens with a size of ϕ10 × 5 cm and the test ages were 28 and 56 days. The sides of the test specimens were coated with epoxy. After drying, the specimens were placed in a vacuum desiccator and subjected to a vacuum process for 24 h to complete the pretreatment process. The test setup is depicted in Figure 3, and the device contained an anode tank and a cathode tank. The test specimens were positioned into the anode tank under controlled conditions, ensuring tight seals to prevent leakage. The cathode tank was filled with 12,000 ml of a 10% NaCl solution and the anode tank with 300 ml of a 0.3 N NaOH solution. A copper mesh was placed in the test tank and connected to the wires, maintaining the controlled environment for the test conducted at a fixed voltage of 30 V for measuring the initial current. The specified voltage and corresponding test time were regulated according to the measured initial current. After the test was completed, the specimen was axially split and sprayed with 0.1 N AgNO3 solution, and the discolored area was observed. Then, the penetration depth was measured, and the chloride ion diffusion coefficient was calculated using the non-steady-state diffusion equation described in NT Build 492.

Test setup of rapid chloride migration test.

The hydration heat test was carried out using a heat box, and the device is shown in Figure 4. The ASTM C1702 was referred to for the test specification, with the specimen casting size of 15 cm × 30 cm. During the test, the data acquisition device was used to measure the temperature data of the specimens, thereby calculating the heat of hydration parameters (unit: kJ/kg). The specimens were placed inside the box, and the temperature was recorded at 30-min intervals. The heat of hydration was then calculated from the temperature data. The results of the test were compared with industry standards.

Device of the heat box.

The SEM used in this study was a 4500M Plus desktop SEM manufactured by SNE in South Korea. The device is shown in Figure 5. The test was conducted by ASTM C1723. The specimens that broke after the compressive strength tests at 56 days were cut into pieces with dimensions of 1 cm × 1 cm × 1 cm. The pieces were dried in an oven (105°C) for 24 h. Then, it was placed on the carrier for the vacuum process, and a 90-s gold plating process was applied to the surface of the specimens. After completing the process, the test operation was carried out and photos were taken. All tests were repeated three times for accuracy and the standard deviation was controlled within 5%.

Test setup of SEM.

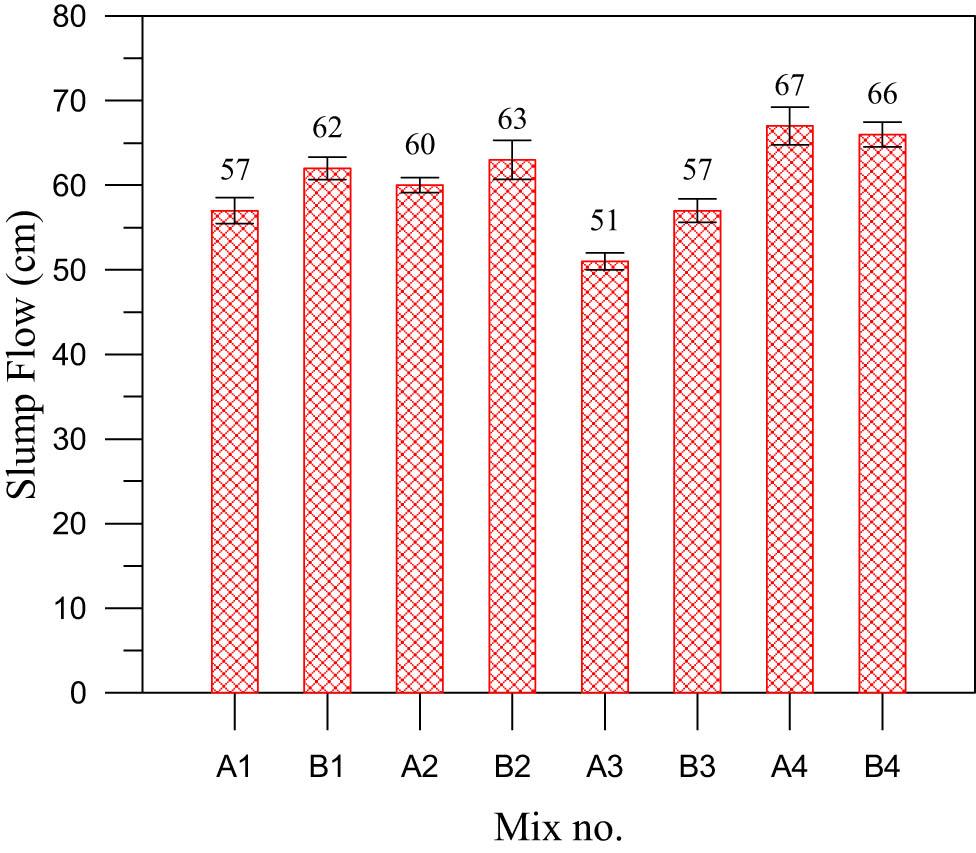

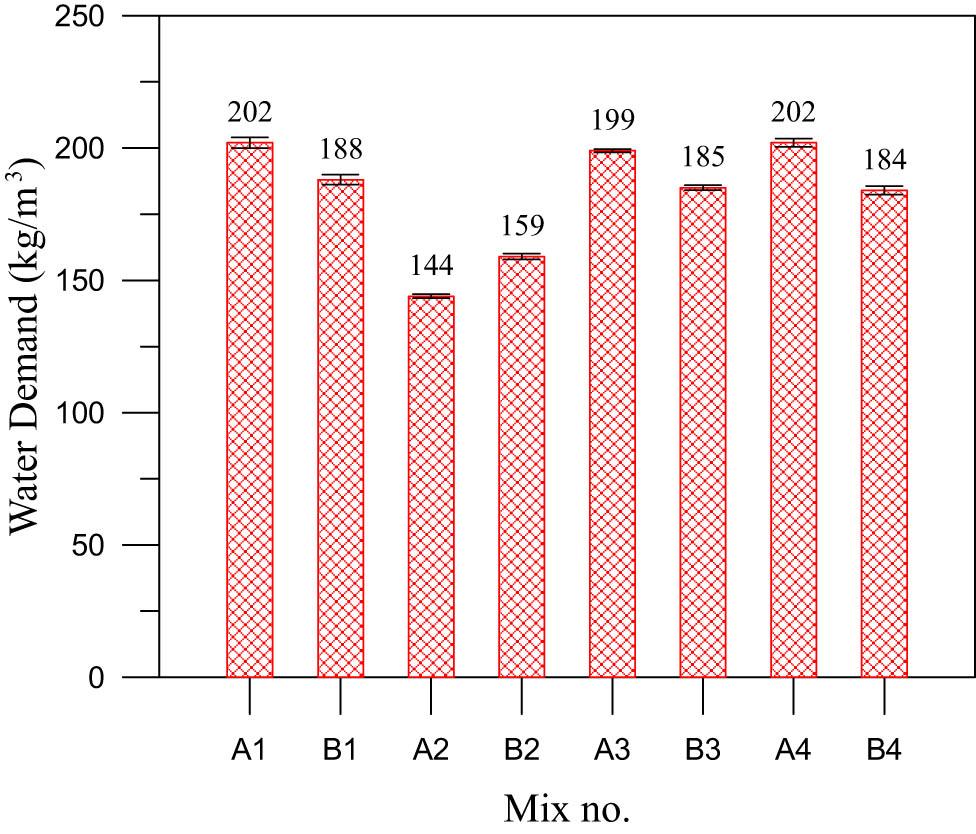

Table 5 summarizes the water demands, superplasticizer dosages, and slump flow values of the eight proportions. From the results of the table, it can be found that the proportion of A2 using blended cement had less water consumption than that of A1 by 58 kg, but it can achieve a better slump flow value than that of A1. However, the proportion of A3 adding silica fume was obviously poorer in workability than that of the other proportions of the same group. The proportion of A4 with the same amount of water consumption as that of A1 and the amount of superplasticizers was less than that of A1, and its slump was 9.5 cm larger than that of the A1 mixture. Therefore, it can be concluded that the A4 mixture was the suitable option for construction. Blended cement can also achieve the slump flow level of the A4 proportion. Compared with the A1 proportion, at a fixed water demand and GGBS dosage, the A4 proportion was highly doped with fly ash. Fly ash has a spherical shape and low calcium content and promotes workability. This result is consistent with the previous studies by Kurda et al. [17], Lin [18], and Sua-iam and Chatveera [19]. Using the lowest amount of cement in the A4 proportions met the need for sustainable building materials with minimal environmental impact [20]. It indirectly validated the advantages of blended cement. The results of this study could help inform cement producers about the potential benefits of using blended cement in construction projects. It could provide an important reference for further research.

Results of flow performances.

| Mix no. | w/b | Water demand (kg/m3) | Superplasticizer dosage (kg/m3) | Slump flow (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 0.32 | 202 | 5.61 | 56 × 58 |

| A2 | 144 | 5.65 | 59 × 61 | |

| A3 | 199 | 5.81 | 52 × 50 | |

| A4 | 202 | 5.28 | 65 × 68 | |

| B1 | 0.39 | 188 | 3.96 | 61 × 62 |

| B2 | 159 | 5.29 | 65 × 61 | |

| B3 | 185 | 4.16 | 56 × 57 | |

| B4 | 184 | 4.25 | 66 × 66 |

The slump test results of Group B (w/b = 0.39) were generally consistent with those of Group A. B2 used 29 kg less water than B1 and achieved a better slump than B1. The slump of B3 was inferior to that of A1, but the difference was not as significant as that of Group A. B4, which used less water and less dosage than B1, also had a better slump than B1, which relatively reflected a better economic efficiency. Compared to the two w/b specimens, the partial replacement of the binders in the mixtures by silica fume also reduced the slump flow [21]. Also attributed to the fine particle size of silica fume, finer particles had a larger surface area [22]. It required more water, which led to a decrease in the workability of the concrete. This implies that blended cement improved the disadvantages of using silica fume and achieved excellent workability results.

Figures 6 and 7 show the comparison of the slump flow values and water demand of each group of specimens. The test results indicate the following: A2 proportion (blended cement) achieved the same workability (slump control at 60 ± 10 cm) by using only 70% of the water consumption of A1 proportion when the w/b and additional additives were the same as those of the A1 proportion. Using the same amount of water in both proportions resulted in severe segregation of blended cement specimens (separating aggregates and pastes due to excessive slumping caused by excessive water utilization). It caused a decrease in strength and an increase in porosity. In addition, it also increased the risk of cracking due to the formation of air bubbles in the mixture. It is because the cement was mixed with more Pozzolans (instead of cement). It had been dry-mixed for 5 min prior to use, which is better in terms of homogeneity than placing all the cementitious materials into mixing equipment individually. The characteristics of the binders were more effectively utilized, resulting in a positive water reduction effect and workability. Such results are consistent with the previous findings by Shao et al. [23] and Widoanindyawati and Pratama [24].

Slump flow for different groups.

Water demand for different groups.

According to the slump flow test results for the A3 proportion (with 5% silica fume additions), the slump flow of A3 was 6 cm smaller than that of A1 (Figure 6), with the same w/b and water consumption. Moreover, A3 specimens had a higher viscosity and a slower flow rate. Although the slump flow of the A3 specimen was still up to 51 cm, its workability was significantly worse than that of the A1 specimen. Silica fume has a fine particle size, making it easy for the concrete to become viscous when added. It is essential to pay special attention to how workability changes during use. Therefore, it is necessary to adjust the amount of silica fume used according to the specific requirements of the concrete mix. It is also essential to monitor how well the system performs when adjusting. A comparison of A4 and A1 slump-flow values (Figures 6 and 7) showed that for the same w/b and water consumption, the slump of A4 was 9.5 cm greater than that of A1. The flowability of A4 was significantly better than that of A1, which was also confirmed from the literature that using more GGBS and fly ash instead of cement increased the flowability of the concrete and that better flowability was associated with reducing water consumption.

A comparison of water consumption and slump-flow values between Groups A and B (as shown in Figures 6 and 7) revealed that for the same ratio of cementitious materials, the corresponding water consumption decreased as w/b increased. On the other hand, blended cement (B2) increased water consumption due to an increase in w/b. However, the water consumption of this proportion was still significantly lower than that of the other proportions with the same cementitious ratio. In this test, only two w/b were tested. It was impossible to know whether this was caused by the characteristics of the blended cement or other factors. More in-depth studies are needed to explore the reasons. In the B3 proportion (an increase in w/b compared to A3 specimens), the amount of silica fume added decreased along with the proportion (the total amount of cementitious material reduced). The workability was still viscous relative to other proportions with the same w/b. However, compared to the A3 proportion (the same proportion with silica fume added), the workability of B3 was still better than that of A3. In addition to the decrease in the total amount of binders, the amount of silica fume used was also inversely proportional to workability (the increase in silica fume used decreases workability), and silica fume had a more significant adverse effect on workability when more amount was applied. Therefore, it can be concluded that silica fume reduces binders and negatively impacts workability.

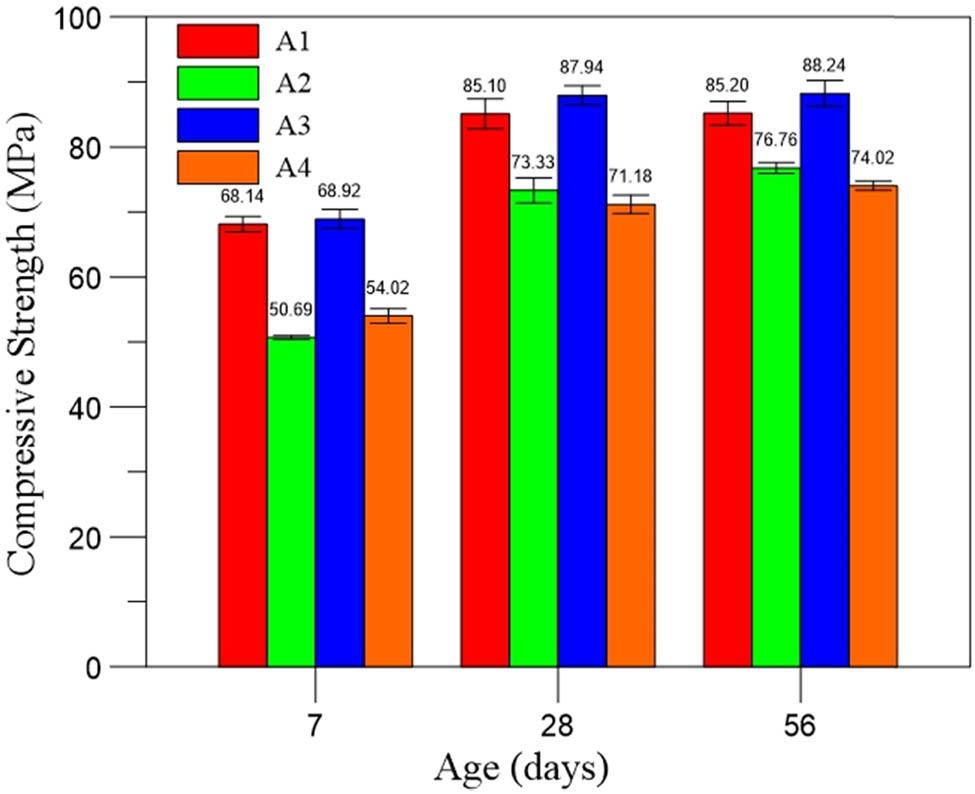

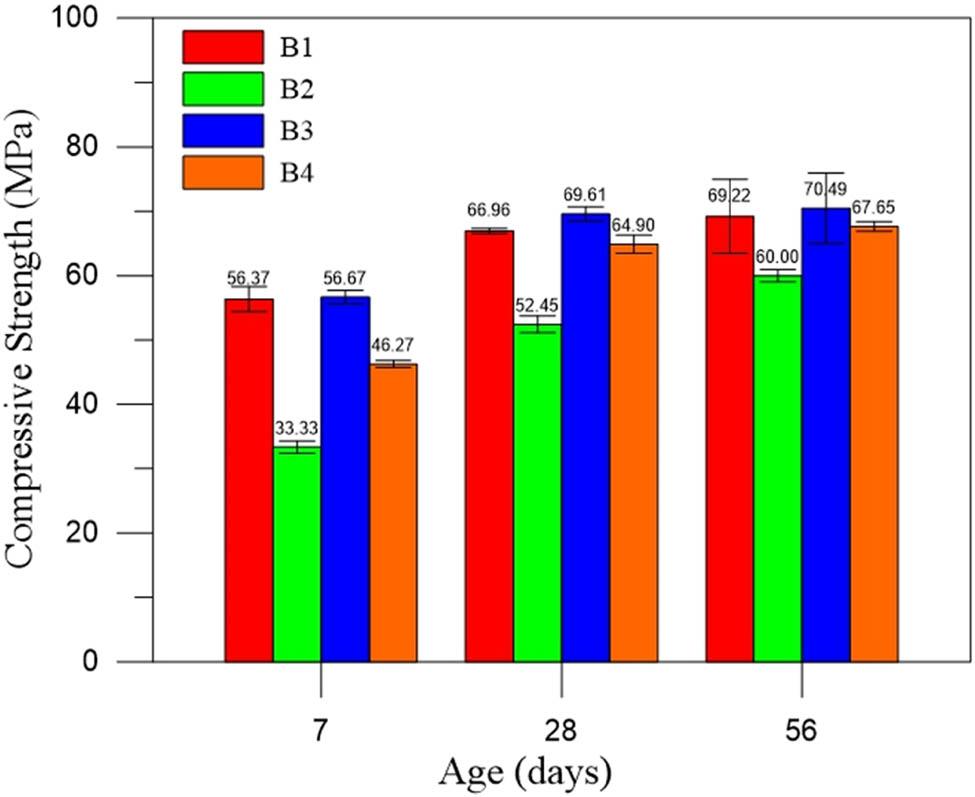

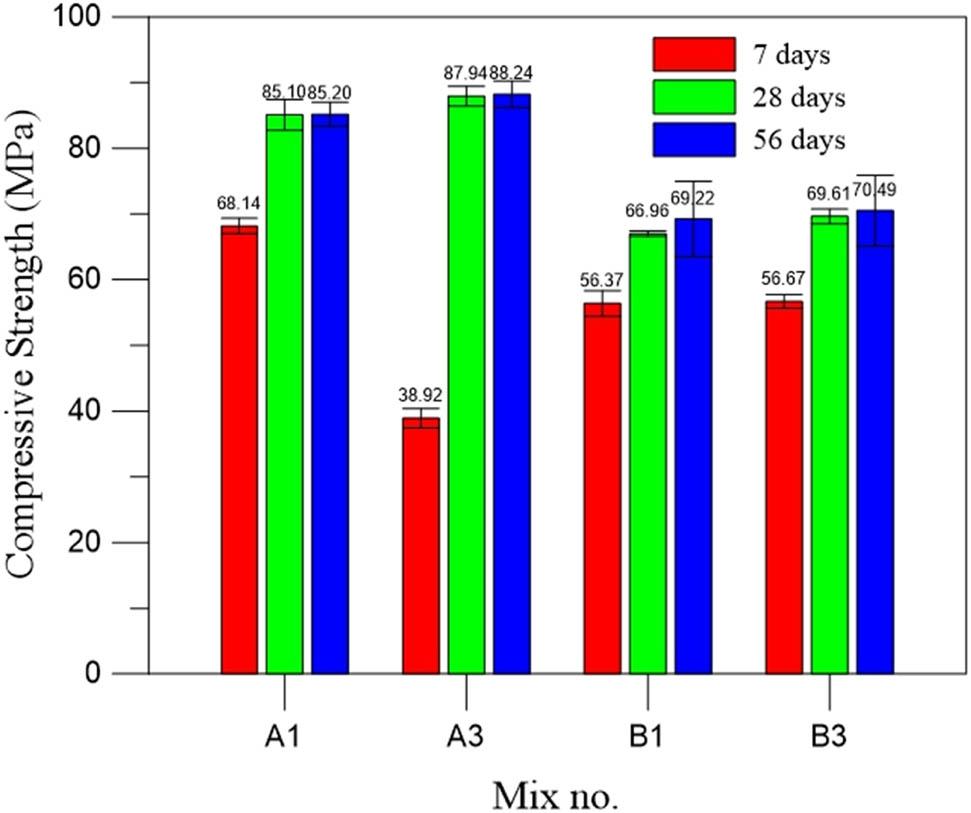

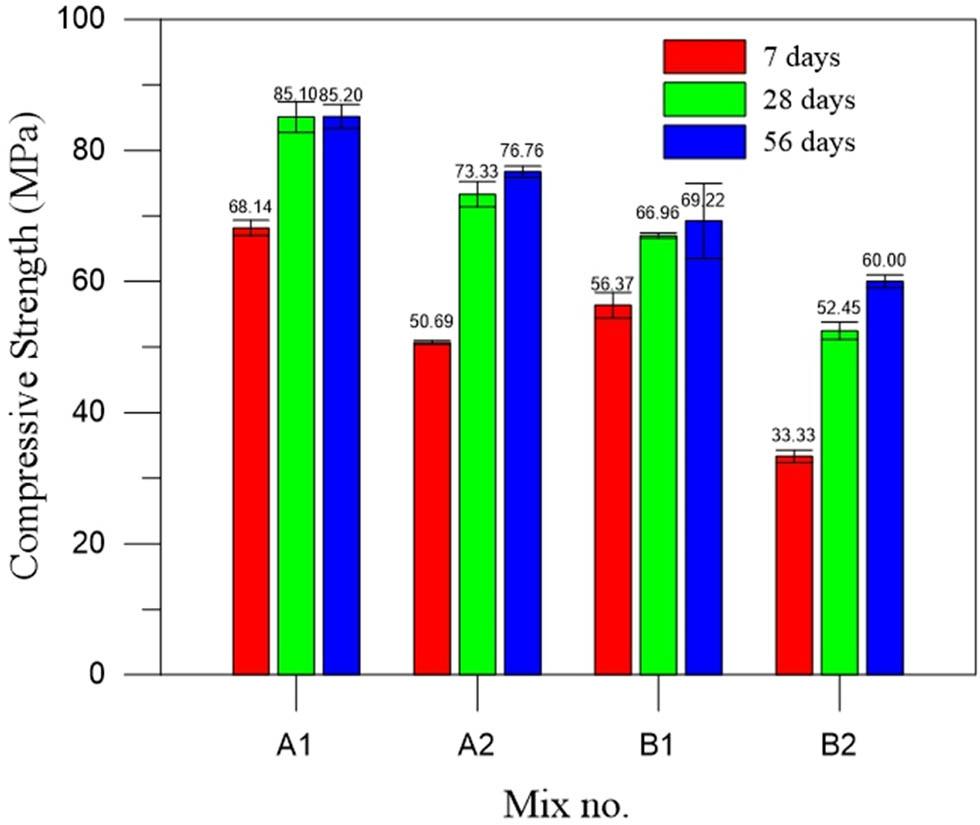

Figures 8 and 9 show the histograms of the strength development of Groups A and B, respectively. The results showed that the highest strengths at 7, 28, and 56 days were obtained for A3 specimens (with 5% silica fume incorporated), followed by A1 specimens (with 50% cement). The increase in compressive strength from 28 to 56 days has shown virtually no increase in A3 and A1 specimens. On the contrary, the compressive strength of A2 specimens (using blended cement) was the lowest in Group A at 7 and 28 days. However, at 56 days, the strength had surpassed that of A4 (with a cement content of 35%), and in the middle and late stages, the growth strength was the highest in Group A proportions. The trend of compressive strength of Group B specimens was the same as that of Group A. From highest to lowest, the strengths were in the following order B3 > B1 > B4 > B2 and B3 specimens, with silica fume being the strongest. In the middle and late stages, growth strength was B2 > B4 > B1 > B3. The B2 specimens, the same as Group A (using the proportion of blended cement), showed the highest growth in the middle and late stages. These premixed pozzolans had a higher specific surface area than the cement particles [25], leading to better strength development in the mid to late stages [26].

Compressive strength for Group A.

Compressive strength for Group B.

From Figure 8, it can be seen that the 7-day strength of Group A from high to low was A3 > A1 > A4 > A2, and the trend was directly proportional to the amount of cement utilized in the proportions. Therefore, it can be inferred that there was a significant relationship between the level of early strength of concrete and the amount of cement applied. Although the cement dosage of A3 specimen was 5% less than that of A1, the 7-day strength was still higher than that of A1, mainly because the 5% silica fume additions to A3 specimen had a large specific surface area and high activity, which produced a pozzolanic reaction with the cement in early development, so that the strength of A3 (45% of the cement) was superior to A1 specimen even though the dosage of cement was less than that of A1 (50% of the cement). The pozzolanic reaction [27] also provided an additional secondary response to the concrete [28], further improving the 7-day strength of the A3 specimen.

For the parts with mid-term strength development (e.g., Figure 8), the strength development was A2 > A4 > A3 > A1 from high to low, which was inversely proportional to the amount of cement used. The proportions with more cement replaced by GGBS and fly ash still showed significant growth in the middle stage of strength development. The 28-day strength of the A2 specimens (blended cement), which used the least amount of cement, even exceeded the strength of the A4 specimens (35% cement). The 28-day strength of A3 specimens (doped with silica fume) was the highest. However, silica fume acted as the Pozzoianic binders along with GGBS and fly ash. It was observed that silica fumes had a higher activity, and the reaction with cement manifested primarily in early strength development. The test results showed that the hydration reaction ability of the silica fume specimens declined tendency in the middle and late stages of concrete development.

In the later strength development (in Figure 8), the strength of the specimens (A1 and A3) with 50% cement and silica fume addition showed almost no growth from 28 to 56 days. This demonstrated that the hydration of these two groups was virtually complete in about 28 days at a w/b of 0.32, and there was not much scope for growth strength in the later period. On the other hand, two specimens (A2 and A4) with higher amounts of cement replacement with GGBS and fly ash were found to have 4–5% strength growth from 28 to 56 days. This indicated that the main strength development of GGBS and fly ash occurred in the middle and late stages of concrete growth strength. The higher the amount of substitution, the more pronounced the growth strength in the later stages. This means that GGBS and fly ash have the potential to improve the mechanical properties of concrete. However, strength gain is not immediate but occurs gradually over time. Fly ash and GGBS reacted with sodium hydroxide in the cement to produce a secondary hydration reaction to form C–S–H colloids [29]. It contributed to the sustainable strength development of the concrete [30].

Figure 9 shows a trend in 7-day compressive strength for Group B. The proportion of cement used in higher percentages gave higher strength in early strength development. The lower the percentage of cement used in the mixture, the lower its 7-day strength. Furthermore, replacing part of the cement with silica fume provided the concrete with a strength comparable to, or even better than, that of highly doped cement in 7 days. In the middle of the strength development of Group B ratios, the growth of the proportion with higher cement content started to slow down. The 28-day compressive strength of the proportion with higher cement content was still lower than that of the proportion with higher cement content. However, there was still a significant trend in growth. A higher cement replacement ratio led to better medium-term strength development. The 7 to 28-day growth strength of B2 specimens (blended cement) was even 1.8 times higher than that of B1 (50% cement as binders), while that of B4 specimens was 1.76 times higher than that of B1 specimens. The growth strengths of B4 specimens were 1.76 times higher than B1, while that of B3 (5% silica fume group) was 1.2 times stronger than B1. However, the growth strength of B3 and B1 specimens showed the same trend of slowing down significantly. The trend in the magnitude of growth strength from 28 to 56 days was the same as that from 7 to 28 days. The 56-day strength was still the highest for the B3 specimen, but the late strength of this proportion was already the lowest of the four proportions, with a growth of 1%. Therefore, it can be inferred that after 56 days, the growth of B3 specimens should be close to 0. B2 specimens (blended cement), which used the least amount of cement, had the highest percentage of pozzolanic materials and had the most significant growth strength from 28 to 56 days. This indicates that blended cement provides more durable and long-lasting strength than ordinary Portland cement. Blended cement can also be used to reduce the overall cost of construction [31].

The results of the compressive strength of Groups A and B using 50% cement (A1, B1) and replacing cement with 5% silica fume (A3, B3) are summarized in Figure 10. It was found that the strength of the group with silica fume was slightly higher. After comparing the four proportions, the growth was very similar. This demonstrated that the silica fume group was close to the cement group or slightly higher than the cement group regarding the hydration rate. Silica fume, like the highly doped cement group, greatly affected concrete strength in the early stages. However, the growth strength slowed down in the middle and late stages (after 28 days). This was particularly noticeable at lower w/b, and these results were related to the high activity of silica fume [32].

Compressive strength of silica fume for different proportions.

A comparison of the strengths of the groups (Figure 11) reveals that the 50% formulation of the cement was much higher than that of the blended cement in the early stages, especially in Group B, where the w/b was higher. From 7 to 56 days, the trend of the strength difference between the two sets of ratios was similar. Until 56 days, the compressive strengths of A1 and B1 were still higher than those of A2 and B2, with a difference in strength of 8.43 and 9.22 MPa, and a difference in the total amount of binders of 193 and 75 kg, respectively. The growth strength in A1 and B1 specimens after 28 days was relatively slow, and even growth strength in the A1 specimen was close to 0. While the strength in A2 and B2 specimens after 28 days still had a certain degree of increase, it should be possible to extend the test time by observing the subsequent strength variations. The long-term strength development of blended cement has the potential to be extremely beneficial in practical applications [33].

Comparison of compressive strength of blended cement.

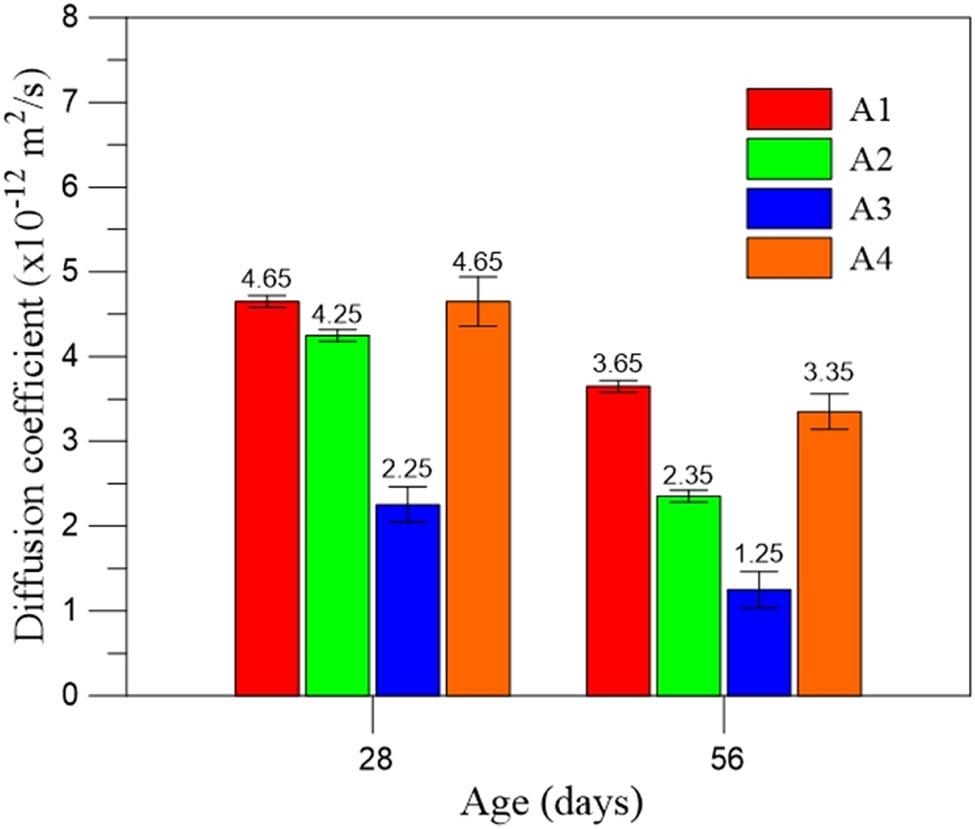

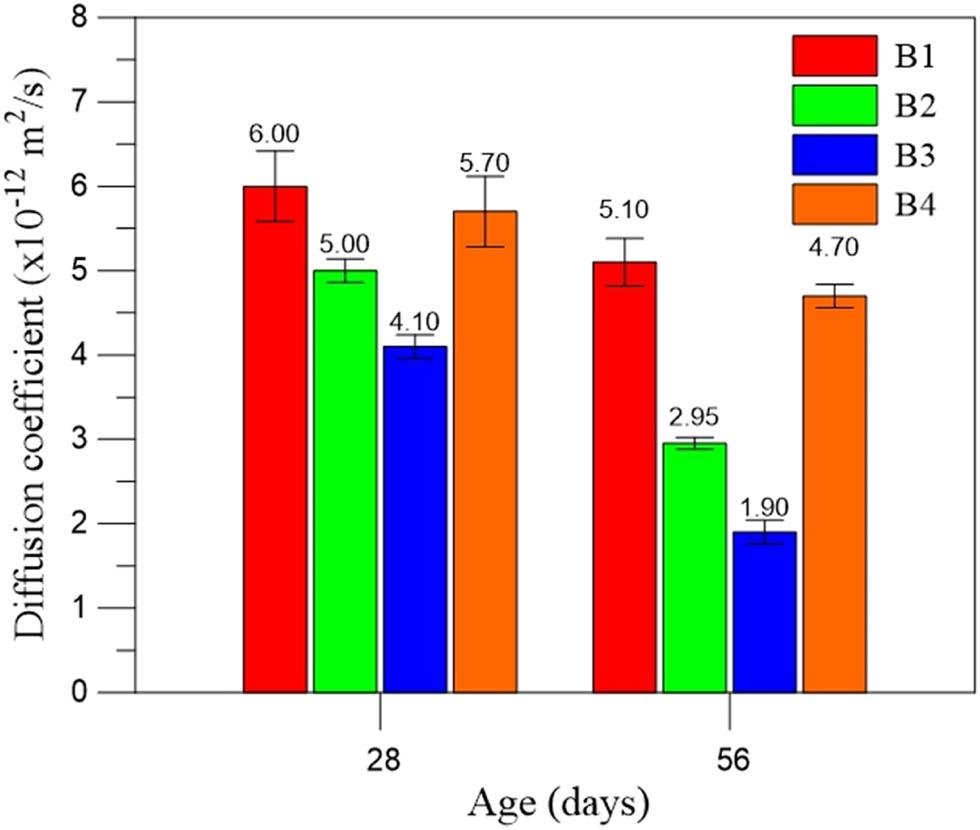

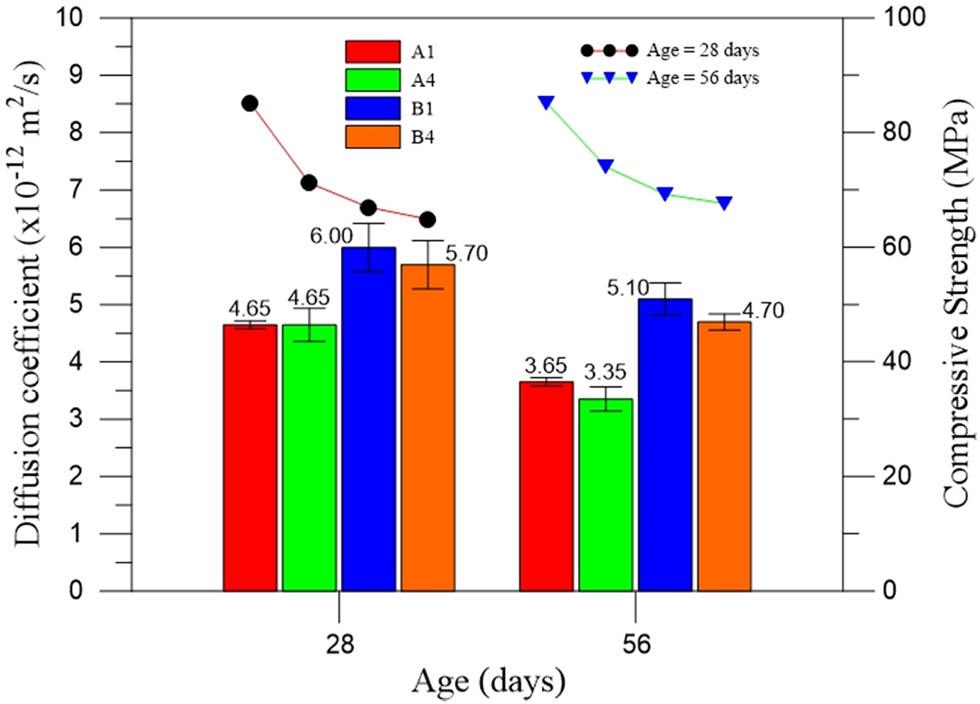

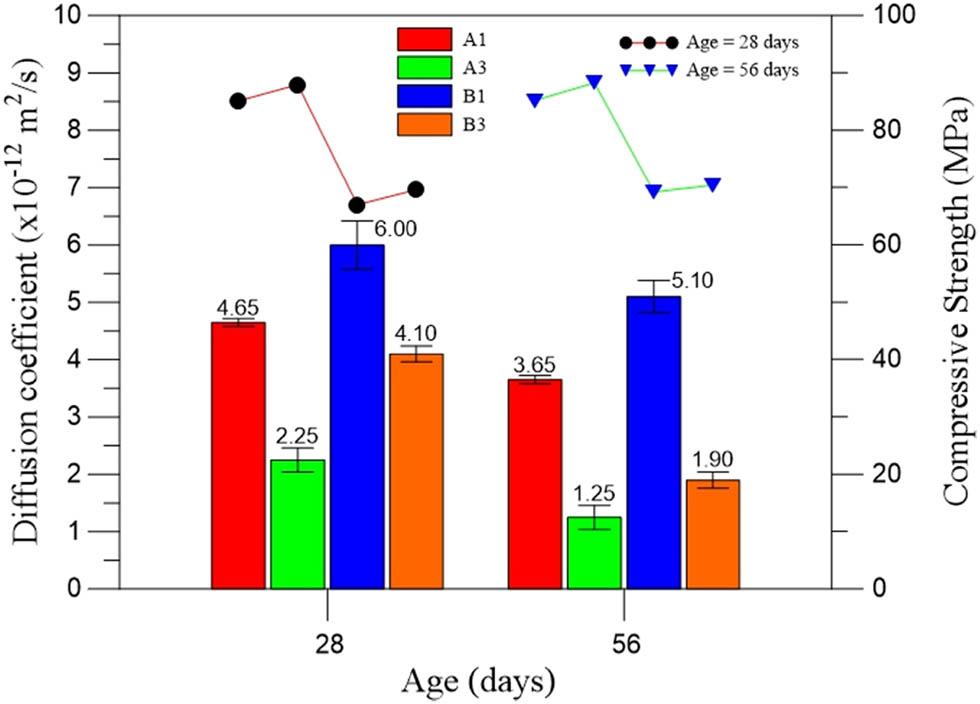

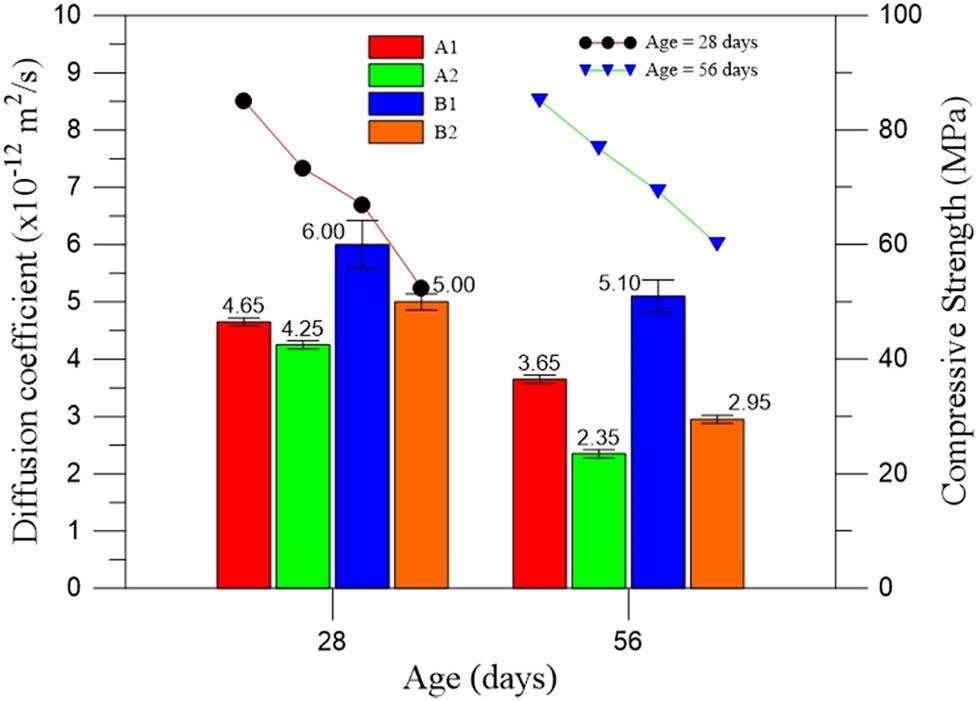

Figures 12 and 13 show the histograms of chlorine ions diffusion coefficients between Group A and Group B at 28 and 56 days, respectively. The test results revealed that the diffusion coefficient ranged from low to high for Group A: A3 > A2 > A4 > A1 and Group B: B3 > B2 > B4 > B1. At both ages, the best resistance to chloride penetration was obtained with the 5% silica fume dosage, followed by specimens with blended cement. The penetration value of the 35% cement formulation was slightly better than that of the 50% cement formulation, but the difference was insignificant. The difference was only 0.3 × 10−12 m2/s at w/b of 0.39 and even the same level at w/b of 0.32. It can be deduced that when cement, GGBS, and fly ash were also used in the binders, altering the proportions of the binders did not significantly affect the permeability coefficients of 28 days, especially at low w/b levels.

Diffusion coefficients for Group A.

Diffusion coefficients for Group B.

The results of diffusion coefficients of the same proportions at 56 days (Figure 14) found that the diffusion coefficients of the two proportions were similar at the same w/b, with a difference of only 0.3–0.4 × 10−12 m2/s, which was the same trend as that at 28 days. Therefore, it can be concluded that under the same w/b and the same amount of binders, altering the proportion of each binder did not significantly influence the chloride ion penetration. It can also be seen from the figure that the level of compressive strength had no direct effect on chloride ion permeability. The strength of A1 was higher than that of A4, but the chloride penetration value was lower than that of A4. Therefore, the primary influence mainly concerned the variation in the w/b, and the lower the w/b used, the better the resistance to chloride penetration. In contrast, the more supplementary cementitious materials were used, the more significant the compressive strength was observed. However, the chloride penetration also increased accordingly. Therefore, it was critical to consider the balance between the compressive strength and chloride penetration when selecting the w/b and amount of supplementary cementitious materials. The results were consistent with previous studies [34], and the w/b had more potential to be influential [35].

Relationship between diffusion coefficient and compressive strength of the proportion of the binders.

In Figure 15, it can be found that the chloride ion permeability coefficient of the specimens with 5% silica fume replacing the cement showed a significant decreasing trend at the same w/b. The two groups at 28 days: A3 was 2.4 × 10−12 m2/s lower than A1, while B3 was 1.9 × 10−12 m2/s lower than B1, which revealed that partial replacement of cement with silica fume had a very significant effect on concrete penetration resistance at 28 days. Observing the trend of compressive strength, it can be seen that the A3 and B3 specimens showed almost no growth in strength from 28 to 56 days. However, the chloride ion penetration coefficient decreased continuously from 28 to 56 days. Apart from the high fineness of silica fume filling the pores in the concrete, the main reason was related to the formation of C–H–S from the hydration reaction between the cement and silica fume. This product filled the pores in the concrete to improve compactness. This phenomenon has also been supported in the literature by using SEM to understand the relationship between the hydration products of silica fume and cement and the resistance to chloride ion penetration. A previous study using artificial intelligence frameworks found that the most critical factor affecting concrete resistance to chlorine ions was w/b, followed by the use of silica fume and then by the amount of cement used. This result is consistent with the present study [36].

Relationship between the amount of silica fume on the diffusion coefficient and compressive strength.

It can be seen in Figure 16 that the proportions using blended cement (A2, B2) had lower chloride ion penetration coefficients at w/b of 0.32 and 0.39 than the proportions using 50% cement (A1, B1). These differences were minor at 28 days, widened at 56 days, and increased up to 2.15 and 3.25 times, respectively, compared to 28 days. It was found that blended cement showed better resistance to chloride ion penetration than 50% cement, especially at 56 days. Studies have shown that blended cement was more resistant to chlorine ion penetration than commonly used concrete mixtures. It was postulated that blended cement, where the binders were subjected to a dry mixing process beforehand, tended to be more homogeneous than the usual mixing method directly into the concrete plant. In addition, the low water consumption also reduced the excess pores in the concrete, making it more densely packed. It was found that mixing blended cement with appropriate mixing techniques (for example, pre-dry mixing in this study) enhanced the microstructure of concrete pastes and that pozzolans were helpful [37]. As a result of the finer particle size of these pozzolans than cement, the effective w/b increased [38]. By promoting hydration compounds, it improved the resistance of concrete to chloride penetration and produced a dense structure [39].

Relationship between the diffusion coefficient and compressive strength of blended cement.

The results of the hydration heat tests with different proportions of binders are shown in Table 6. The w/b of the test was set at 0.40. The test results revealed that the higher the proportion of cement used, the greater the value of its hydration heat. Blended cements (the amount of cement used was less than 35%, the proportion of which was unavailable due to patent reasons) reflected the lowest hydration heat because they contained the least amount of cement. Using 5% silica fume as binders gave the highest heat of hydration values compared to the other three groups. The blended cement reduced the hydration heat by 38% at 28 days and 36% at 56 days compared to specimens containing 5% silica fume. This suggested that blended cement was an effective and economical choice for reducing the heat of hydration in concrete. Compared to the highly doped cement group, the blended cement achieved a significant reduction in the heat of hydration, mainly in the early stages of hydration [40], and then stabilized the tendency of the release of heat after 70 h of hydration [41], which also contributed to the lower heat of hydration of the blended cement compared to the other three proportions. In construction applications where heat management is critical, blended cement became an ideal choice.

Results of hydration heat (unit: kJ/kg).

| Proportion of binders | 28 days | 56 days |

|---|---|---|

| Cement:GGBS:fly ash = 50:35:15 | 250.0 | 292.5 |

| Cement:GGBS:fly ash = 35:35:30 | 233.6 | 274.2 |

| Blended cement | 188.4 | 210.3 |

| Cement:GGBS:fly ash:silica fume = 45:30:20:5 | 303.6 | 330.8 |

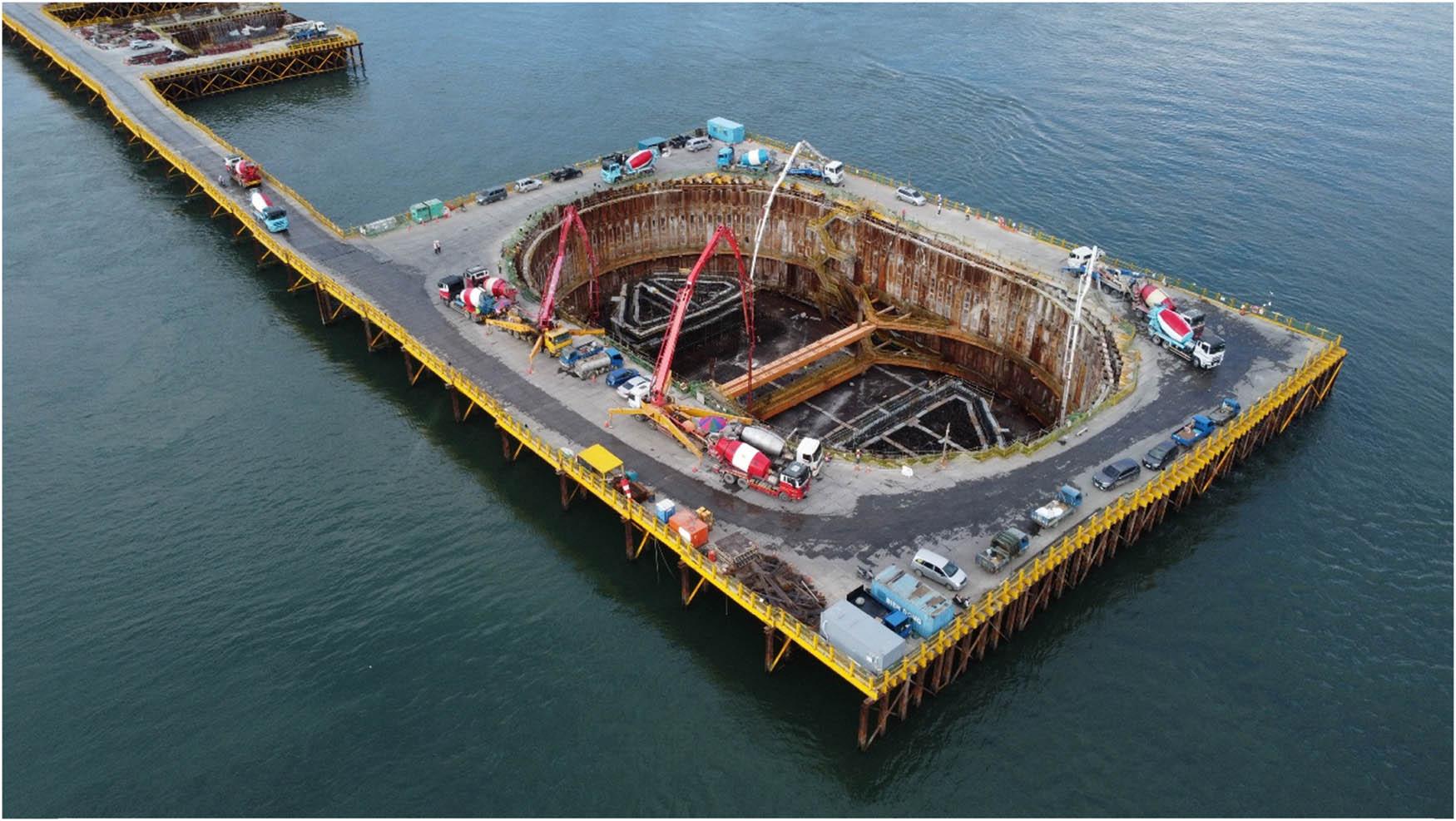

Furthermore, blended cement can reduce the amount of cement used in concrete, reducing the associated environmental impacts. Blended cement has even more advantages when applied to mass concrete. This study applied blended cement to the concrete of the main piers of the newly constructed Danjiang Bridge in Taiwan (expected to be completed in 2025). The photograph of the concrete placement is shown in Figure 17. This proportion met the basic requirements for compressive strength, chloride diffusion coefficient, and hydration heat for the new Danjiang Bridge construction. As in recent research [42], blended cement reduced the potential risk associated with concentrated heat released from mass concrete.

Construction diagram of Danjiang Bridge using blended cement from this study.

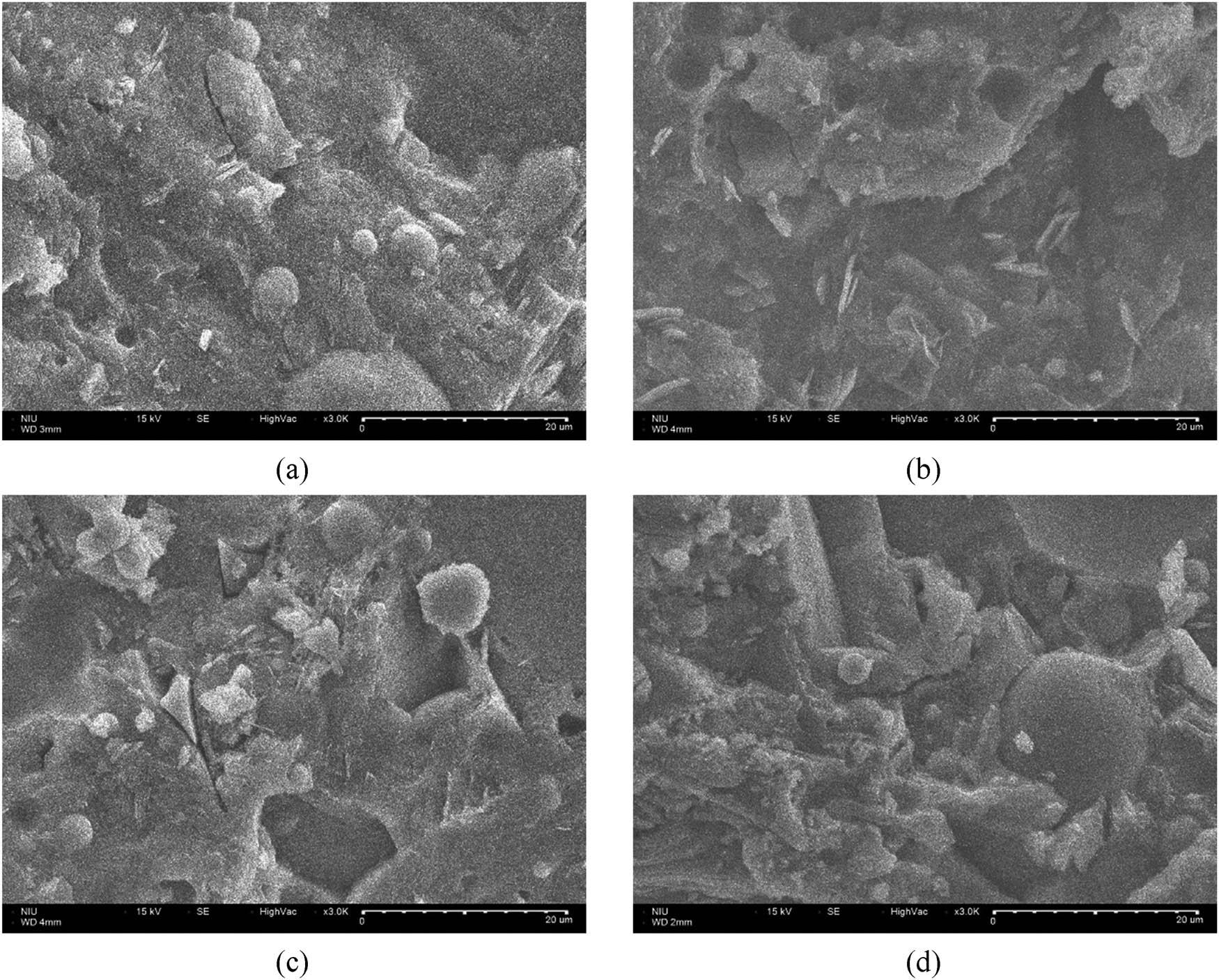

SEM was used to observe the microstructure of the specimens and verify the effect of different proportions of binders on their properties. The SEM photographs of the four sets of specimens with w/b of 0.32 are shown in Figure 18. The SEM image for Figure 18(a) reveals a heterogeneous microstructure typical of the A1 specimen. No major cracks or fractures were readily apparent in this field of view. However, the plate-like structures, particularly in the central area, exhibit angular edges detached from the surrounding matrix. It suggested potential microcracking or interfacial weakness between different phases within the cement paste under higher compressive strength. Given their spherical morphology, the rounded features scattered throughout might be fly ash particles. The binder proportion of 50:35:15 (cement:GGBS:fly ash) suggested a significant amount of GGBS, which can contribute to a denser microstructure over time due to its slower reaction rate than cement. Overall, the microstructure appeared to be complete and dense. The SEM image for Figure 18(b) shows a heterogeneous surface morphology. There appeared to be a relatively dense, textured matrix, possibly composed of hydrated products, with more oversized, irregular, and lighter-toned regions. These regions could be unreacted cement particles or areas with a different composition/porosity. Plate-like or lamellar structures, identified as calcium oxide, were scattered throughout the matrix and particularly noticeable in the lower half of the image. These structures appeared to be randomly oriented. In contrast, no spherical particles of incomplete reaction were observed on the surface. Hydrides such as calcium hydroxide may be the main reason why the strength of the specimens is slightly lower than that of the other groups. Therefore, maintenance for more than 91 days allowed the hydration reaction of the specimens to be completed, which reflected better strength development.

SEM images for A series specimens (×3,000). (a) A1 specimen, (b) A2 specimen, (c) A3 specimen, and (d) A4 specimen.

Figure 18(c) reveals the SEM for the A3 specimen. The image showed a relatively dense microstructure with less visible pores. The pores appeared generally irregular in shape and vary in size. Given the stated low permeability coefficient, these pores were likely discontinuous and not interconnected, contributing to the material’s impermeability. The dense packing of hydration products further supported this conclusion. No major or distinct cracks were readily apparent in this particular field of view. The material appeared intact mainly at this magnification. It was verified to have the highest compressive strength and the lowest permeability coefficient. The surface exhibited a textured morphology, primarily composed of a fine matrix interspersed with needle-like formations identified as C–S–H colloids. These C–S–H colloids indicated pozzolanic reactions between the SCMs (GGBS, fly ash, and silica fume) and the calcium hydroxide produced by cement hydration. Some larger, rounded particles (potentially unreacted fly ash) are also observed. The overall impression was of a well-reacted and dense surface, consistent with the reported high compressive strength. The high proportion of SCMs (55%) in the binder likely contributed to the refined pore structure and the abundance of C–S–H, leading to the observed superior mechanical and transport properties. Figure 18(d) shows the SEM image of the A4 specimen with 30% fly ash dosage. The image suggested a relatively porous structure. There were several larger, rounded voids, mainly two prominent ones near the center. A network of finer pores also appeared to be distributed throughout the matrix. This high porosity correlated with the stated high permeability coefficient. While no distinct macro-cracks were readily apparent in this field of view, the irregular boundaries between different phases and the apparent gaps around some larger particles suggested potential zones of weakness where cracking could initiate. The surface appeared rough and uneven. The various components of the mixture (cement, GGBS, and fly ash) were distinguishable, with some areas appearing denser than others. The spherical particles, likely fly ash, were prominent and varied in size. The texture suggested incomplete integration of the different constituents, which could contribute to the lower compressive strength. The rough surface also supported the observation of high porosity, which is consistent with the strength and diffusion coefficient results.

Concerning research results published in recent years, this study found that for every ton of cement produced, approximately 850 kg of carbon emissions would be generated [43]. The carbon emissions of GGBS [44], fly ash [44], and silica fume [45] amounted to 83, 8 and 14 kg/tons, respectively. The carbon emissions of aggregates and chemical additives were referenced from literature published in 2022 [46] and in 2024 [47]. The blended cement was calculated by the ready-mix concrete plant using the proportions of the various binders. The corresponding carbon emissions of the concrete components calculated in this study are summarized in Table 7. A summary of the converted carbon emissions for the eight proportions used in this study is shown in Table 8. As shown in Table 8, the carbon emission calculations confirmed that cement was the primary source of carbon emissions among concrete constituents. The higher the amount of cement used, the higher the carbon emissions. The remaining binders, which produced less carbon dioxide, significantly reduced the carbon footprint of the concrete by replacing portions of cement. In particular, the proportion of blended cement required was only 42% of the 50% cement required at w/b of 0.32 and 49% of the 50% cement used at w/b of 0.39. This shows that blended cement had a significant effect on the reduction of carbon emissions. Blended cement has the potential to reduce carbon emissions by up to 50%. With 50% replacement of supplementary cementitious materials in blended cement, carbon emissions were reduced by more than 35% for different proportions of the binders. This study achieved a lower reduction in carbon emissions (more than 45%) compared to other studies by Lin et al. [47], Fakhri and Dawood [48], and Kaplan et al. [49]. Thus, it is an important option for reducing the environmental impact of concrete.

Carbon emission calculation parameters (kg/tons).

| Concrete component | Cement | GGBS | Fly ash | Silica fume | Blended cement | Aggregates | Additives |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon emissions | 850 | 83 | 08 | 14 | 196 | 30.3 | 9.9 |

Converted carbon emissions for the eight proportions (kg).

| Mix no. | Cement | GGBS | Fly ash | Silica fume | Blended cement | Aggregates | Additives | Carbon emissions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 330 | 231 | 99 | — | — | 1,478 | 5.61 | 345.3 |

| A2 | — | — | — | — | 467 | 1,771 | 5.65 | 145.2 |

| A3 | 297 | 198 | 132 | 33 | — | 1,466 | 5.81 | 314.9 |

| A4 | 231 | 231 | 198 | — | — | 1,448 | 5.28 | 261.0 |

| B1 | 247.5 | 173.3 | 74.3 | — | — | 1,672 | 3.96 | 276.1 |

| B2 | — | — | — | — | 420 | 1,784 | 5.29 | 136.4 |

| B3 | 222.8 | 148.5 | 99 | 24.8 | — | 1,664 | 4.16 | 253.3 |

| B4 | 175 | 175 | 150 | — | — | 1,640 | 4.25 | 214.2 |

Table 9 shows the cost of concrete ready-mix plants based on the unit price of each concrete component according to the current situation in Taiwan. The calculated costs for the eight groups are shown in Table 10. Tables 9 and 10 show that cement had the highest price per unit of the binders used in this study, apart from silica fume. As a result, the higher the proportion of cement used in the same w/b, the higher its cost. Silica fume was much more expensive than other binders. The price of proportions had to be increased due to the increase in silica fume. Although silica fumes provided superior early strength and resistance to chloride ion penetration, utilizing silica fumes to replace other binders was not economical unless necessary. Overall, blended cement effectively reduced the cost, evident at low w/b. Moreover, blended cement had superior performance in resisting chloride ion penetration and reducing carbon emissions. The low cement dosage characteristics also helped minimize hydration heat to a certain extent, so blended cement had relatively high economic efficiency. Moreover, blended cement are environmentally friendly and can be used in a variety of applications. They are especially suited for marine environments due to their resistance to chloride ion penetration.

Prices of the concrete components used in this study (US$/kg).

| Concrete components | Cement | GGBS | Fly ash | Silica fume | Blended cement | Aggregates | Additives |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Price | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.50 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 1.00 |

Converted raw material costs for the eight proportions (US$).

| Mix no. | w/b | Cement (kg) | GGBS (kg) | Fly ash (kg) | Silica fume (kg) | Blended cement (kg) | Aggregates (kg) | Additives (kg) | Cost (US$) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 0.32 | 330 | 231 | 99 | 1,478 | 5.61 | 75.60 | ||

| A2 | 467 | 1,771 | 5.65 | 63.37 | |||||

| A3 | 297 | 198 | 132 | 33 | 1,466 | 5.81 | 88.10 | ||

| A4 | 231 | 231 | 198 | 1,448 | 5.28 | 68.70 | |||

| B1 | 0.39 | 247.5 | 173.3 | 74.3 | 1,672 | 3.96 | 64.90 | ||

| B2 | 420 | 1,784 | 5.29 | 60.07 | |||||

| B3 | 222.8 | 148.5 | 99 | 24.8 | 1,664 | 4.16 | 73.37 | ||

| B4 | 175 | 175 | 150 | 1,640 | 4.25 | 60.43 |

This study addressed the situation regarding the application of actual concrete to field works. The results are summarized as follows:

-

GGBS and fly ash combined in concrete improved workability. The w/b strongly affected the penetration of chloride ions, but the amount of GGBS and fly ash was noticeable.

-

Silica fume increased the early heat of hydration, which reduced workability, especially at low w/b. The concrete temperature (e.g., when placing mass concrete) and the amount of silica fume must be considered. Because of its high cost, it was less attractive.

-

Blended cement reduced the water demands and workability requirements at the fixed w/b.

-

Blended cement significantly outperformed other mixes in chloride penetration resistance, particularly at later stages. At w/b of 0.39, blended cement showed a diffusion coefficient considerably lower than 50% cement specimens at 56 days. Lower cement content in blended cement demonstrated excellent performance in later strength development, highlighting the superior durability of concrete.

-

Premixed blended cement is cost-effective and eco-friendly, with significantly lower CO2 emissions than other cement mixes.

-

Blended cement showed better engineering performance than normal concrete and had potential for use in the construction industry.

This study was financially supported by the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC) in Taiwan under project NSTC 111-2923-E-197-001-MY3 and the Grant Agency of the Czech Technical University in Prague under project no. SGS24/116/OHK1/3T/11.

Kae-Long Lin: Investigation, Methodology, Writing - Original Draft. Wei-Ting Lin: Conceptualization, Resources, Methodology, Formal analysis, Visualization, Supervision, Validation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing. Lukáš Fiala: Investigation, Methodology, Writing - Review & Editing. Jan Kočí: Data Curation, Methodology, Writing - Review & Editing. Po-En Lee: Data Curation, Writing - Review & Editing. Hui-Mi Hsu: Data Curation, Writing - Review & Editing.

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.