The 85-d-long eruption of the Tajogaite volcano (September 19–December 13, 2021) was a minor episode on the geological timescale but caused fundamental landscape changes in areas around the active craters. The factors driving these changes included erupting lava, pyroclastic material fallout, and toxic gases and fumes being emitted from the volcano and lava flows as late as May 2023. These changes affected primary (natural) and semi-natural landscapes. This includes the volcanic ridge of Cumbre Vieja, designated as a nature park (Parque Natural de Cumbre Vieja). This area has typical features of a young volcanic landscape, renewed through successive historical eruptions (Historia volcánica…): 1470, 1585, 1646, 1677, 1712, 1949, 1971, and 2021 (Fig. 1). Changes in cultural landscapes also occurred in on the central part of the island, on the western slopes of the Cumbre Vieja ridge and within the medianías (1) elevation zone in areas shaped by older volcanic eruptions. These areas have been inhabited since at least the fourth and fifth centuries CE and cultivated for centuries, featuring a modern technical infrastructure. At the time of the Spanish conquest (1472), the northwestern part of the island, which has the most favourable environmental conditions, was inhabited by the Bonahoaritas and Auaritas peoples of Berber origin. They were primarily engaged in sheep and goat herding and gathering, minimally transforming the environment. Their population is estimated to be approximately 4,000. There is no evidence to suggest that the western slopes of Cumbre Vieja were inhabited before the arrival of the Spanish (Viña Brito 2023). However, volcanic eruptions may have buried all traces of human presence. Even if they had been inhabited, the ‘palimpsest’ of the island is unreadable. Gradual landscape changes began with the island's incorporation into the Crown of Castile and immigrant arrivals.

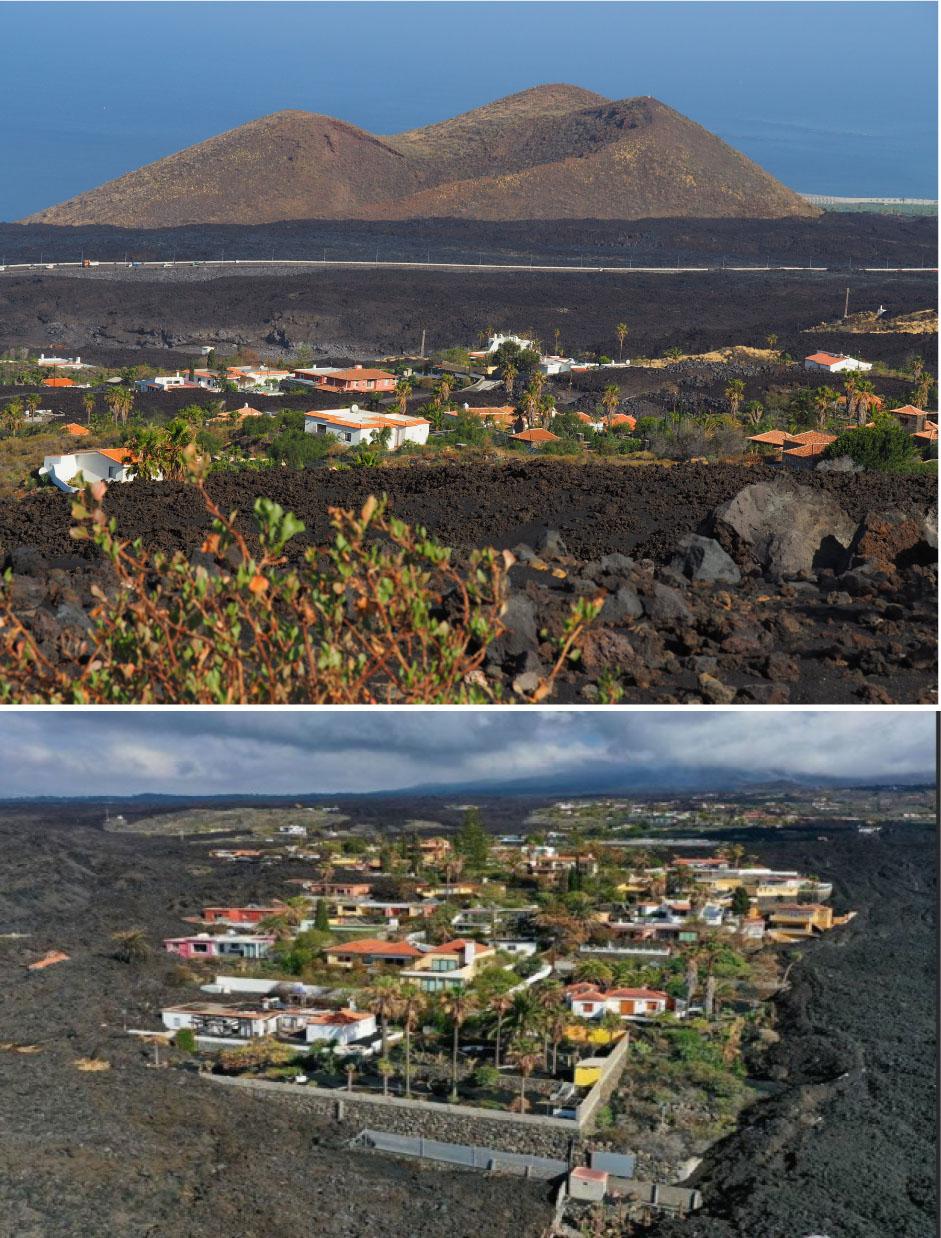

Cumbre Vieja Natural Park has the characteristics of a primaeval landscape, with numerous young volcanic cones and a cover of pyroclastic deposits. The landscape state after the eruption of Tajogaite

Source: photos taken by Authors

In the last decade of September 2021, when the Tajogaite Volcano had been active for only a few days, we posed questions about the impacts of the eruption. This includes the extent of landscape transformations it caused, the factors driving these changes, their depth, direction, and consequences. Natural disasters and particularly volcanic eruptions are always dramatic events for both nature and the communities they affect. However, the effects of such disasters are substantially more prominent on islands, especially those that are smaller in size. Economic history has shown profound economic and social transformations in these environments following cataclysms such as cyclones, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and tsunamis (Jędrusik 2001, 2005, 2008, 2014). With smaller land areas, the adaptive capacity of communities is substantially less than that of larger territories. La Palma (706 km2) is one of those small, inherently more vulnerable territories. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to identify the factors influencing landscape change and their extent, depth and directions following the Tajogaite volcanic eruption.

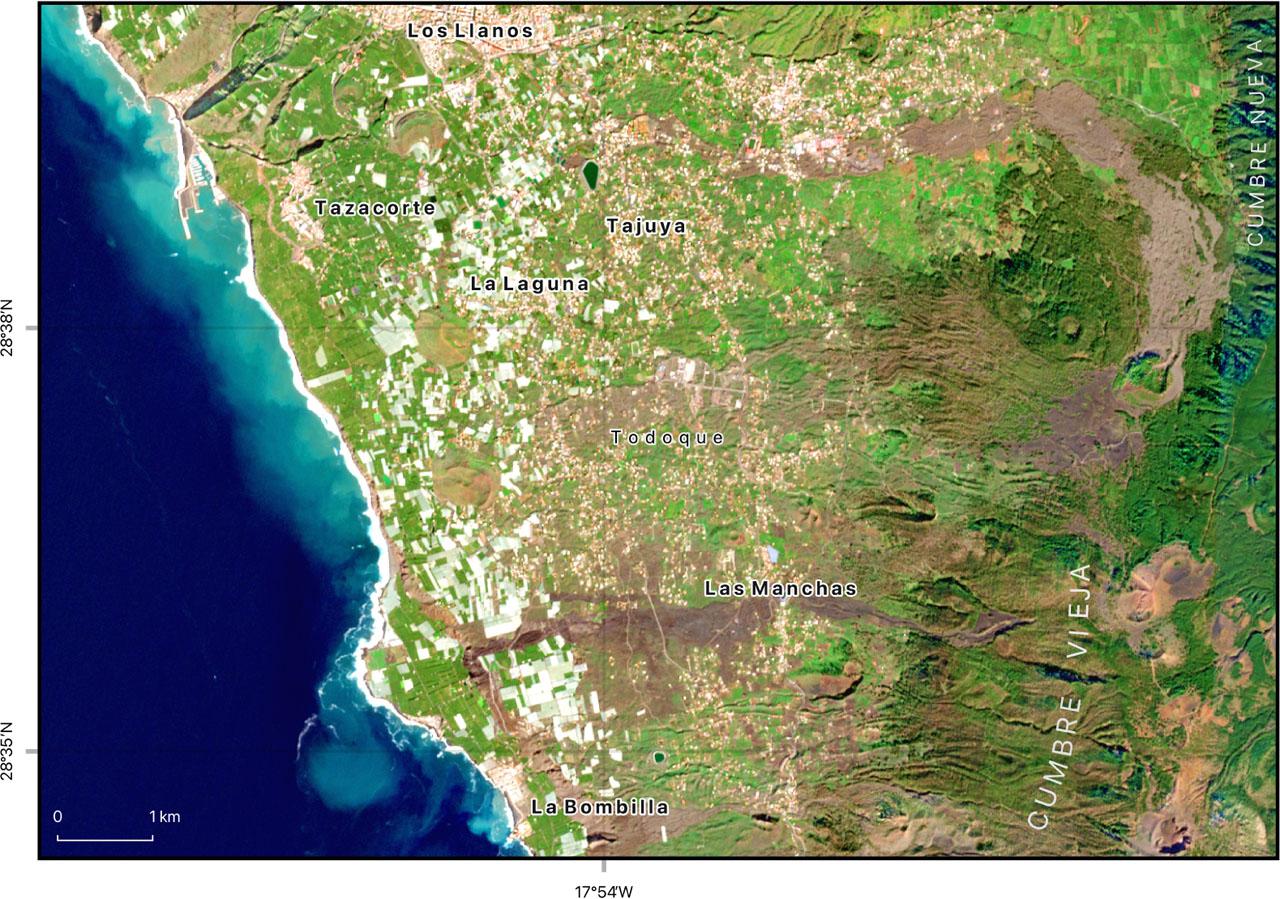

The study area encompassed a section of the western slopes of the volcanic ridge Cumbre Vieja. This is referred to in the literature by the acronym CVVR (2) and was affected by the 2021 volcanic eruption. It extends between 28°39′N, passing approximately through the towns of Tazacorte and Paso de Abajo, and the latitude 28°35′N, near the town of Puerto de Naos on the island's western coast. To the east, the study area includes the summit zone of Cumbre Vieja between these latitudes. Meanwhile, to the west, it is confined to the young subaqueous deltas marking the endpoint of lava flows associated with the eruption. The study area covers approximately 70 km2 and includes the area with the most visible landscape transformations, documented on satellite imagery, drone photographs and professional and amateur ground-level photographs. The broader context of this area includes the entire volcanic island of La Palma and the entire western Canary archipelago, where volcanic ash fallout from the Tajogaite eruption was recorded.

The western slopes of the Cumbre Vieja ridge are a stage for an ongoing conflict between the forces of nature and have been active since the start of the Quaternary (Mangas 2023), and subsequent human activity. On La Palma, primary landscapes with distinct features, including volcanic cones, craters, solidified lava flows and pyroclastic deposits coexist with equally distinct cultural landscapes with clear stratigraphy. These landscapes are naturally open and dynamic systems, with processes that generate contrasting changes. Natural phenomena are not strongly influenced by human actions and their presence in the landscape. Conversely, human activities, including environmental transformations to meet their needs and the culturalization of the landscape, are often powerless against natural forces. This frequently leads to the renaturalization of landscapes. The expansion of cultural landscapes sometimes spans generations, advancing at the cost of ecological balance disruption through the introduction of anthropogenic elements, creating quasi-natural landscapes (Myga-Piątek 2012). Renaturalization of cultural landscapes, most often following endogenic processes such as volcanic eruptions and earthquakes or exogenic processes including landslides, occurs at the expense of cultural landscapes and typically unfolds rapidly.

In May 2023, field research was conducted, involving interviews, observations and data collection. Six people participated in the study, comprising four people from the Polish side and two from the Spanish side. The Spanish researchers organized the logistics of the in situ study and acted as guides and intermediaries with local authorities during the fieldwork. The immediate vicinity of the active volcano in May 2023 was partially inaccessible and under the control of local services. Movement in the area was limited due to road destruction, locally dangerous high ground temperatures and gas emissions. The research participants had their own transport and the necessary permits issued by the Cabildo Insular de La Palma.

The effects of the Tajogaite eruption were observed by the research team in May 2022 and May 2023 during several days of field studies. The field research was preceded by preparatory work in the office. This included studying available cartographic and textual materials, photographs taken in situ by researchers from the Universidad de La Laguna during and after the eruption and analyzing satellite imagery. Articles and comments from daily newspapers and online were also reviewed. Particularly valuable information was found on the official websites of the Cabildo de La Palma. A key information source was agency and amateur videos documenting the eruption, as well as Spanish-language blogs available online. This was likely the first volcanic eruption of such a long duration to be filmed almost continuously, day and night, in its entirety. Information about the eruption's progress spread worldwide. The conclusions from field observations and photographic documentation collected during the reconnaissance in 2022 were reanalyzed.

The primary method of fieldwork was observation. Visual impressions (views, panoramas) were complemented by organoleptic studies. Sensory data also contributed to the preparation of explanatory descriptions. The field research was conducted according to a plan developed by researchers from the University of La Laguna and was updated multiple times, including during the field stay. During the fieldwork, visits were made to several institutions involved in addressing the challenges arising from the volcanic disaster. In-depth interviews were conducted with their managers and employees, and information about the effects of the Tajogaite eruption and proposed adaptive strategies was reviewed.

Due to unforeseen limitations, field studies sensu stricto were performed at selected locations on the western slopes of Cumbre Vieja, mostly at the edge of the lava cover, at the boundary between lava flows and areas buried under lava deposits and on pyroclastic material covers. Particularly interesting were areas that had been inhabited and that had been developed before the eruption. The condition of these areas allowed researchers to understand the mechanisms of landscape transformation. The well-preserved traces of the 1949 eruption of the San Juan volcano, which devastated areas adjacent to those destroyed by the Tajogaite Volcano in 2021, were also a subject of observation, analysis, and comparison. Photographic documentation was created during all field observations (Fig. 2–5).

Tajogaite cone – a new element in the landscape of La Palma island – as of May 9, 2023 (28°37′40″N; 17°55′51″W)

The photograph shows the structure of the surface of the lava cover. On May 8, 2023, when the photograph was taken, the stream of lava that had solidified on the surface emanated heat felt by the research team.

A house buried partially under the lava flow, covered with volcanic ash.

A road flooded with lava in the town of Los Llanos de Aridane (28°37′21″N; 17°52′25″ W).

Source: photos taken by Authors

The field research was complemented by office-based analyses of current imagery from the Sentinel-2 satellite mission and the PlanetScope nanosatellite constellation. The need to use these resources for data for the period before and shortly after the eruption became evident after returning from the field. Sentinel-2 captures high-resolution optical images. When using visible spectrum channels, the spatial resolution of the data is 10 m (Zagajewski et al. 2024). These images were used to create the RGB (3) composition depicting areas affected by the eruption. The pixel size of PlanetScope data is 3 m, enabling analysis of landscape changes.

Before the 2021 eruption, La Palma was an island with established agricultural traditions. Agriculture thrived due to favourable terrain, a beneficial and relatively humid climate, and the residents' skilled use of water resources for irrigation (Cabildo de La Palma 2024). This enabled the gradual development of settlements and the economy, including the preparation of extensive areas for irrigated crops and the infrastructure supporting this purpose. Such development occurred in Llanos de Aridane, Tazacorte, Todoque, La Laguna and Tajuya. Here, banana and vine cultivation flourished from the mid-20th century, alongside smaller-scale avocado and vegetable farming. Tourism did not play a substantial economic role, but it has been present in the Aridane Valley. Approximately 1000 hotel and non-hotel beds were destroyed by the Tajogaite eruption and around 4000 beds were left unusable for many months.

The landscape of the studied area before the eruption is shown in the RGB composition (Fig. 6). This map was created using cloud-free imagery captured by the Sentinel-2 satellite, which is a critical factor for accurate interpretation when working with colour compositions that use the visible spectrum of electromagnetic waves. QuantumGIS (QGIS) software was used to develop the map, including the labelling of key towns and mountain ranges, such as Cumbre Vieja and Cumbre Nueva.

Contemporary image obtained from Sentinel-2A satellite. Photo was taken before the eruption of Tajogaite Volcano on 28.01.2021. The RGB composition of the photo contains three colour bands: red (Band 4), green (Band 3) and blue (Band 2)

Source: own elaboration based on Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem, https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/

The imagery shows the spatial arrangement of buildings and agricultural areas, the varied topography and the modern coastline, defined by the extent of the lava cover. South of the town of Las Manchas, traces of the 1949 San Juan volcano eruption could be identified, distinguished by a darker phototone.

The area of the most substantial landscape transformations was inaccessible for direct field research for over a year. However, satellite imagery made it possible to prepare another RGB composition (Fig. 7). The map shows the extent of the young lava cover, which formed in a fan-like shape, spreading westward from the base of the Tajogaite cone along the line of steepest descent on the slopes of Cumbre Vieja, extending beyond the pre-eruption ocean shoreline. Measurements established its length to be approximately 6.5 km with a maximum width of approximately 3.5 km.

Contemporary image obtained from Sentinel-2A satellite. Photo was taken after the eruption of Tajogaite Volcano on 17.02.2022. The RGB composition of the photo contains three colour bands: red (Band 4), green (Band 3) and blue (Band 2). Legend: 1 – Tajogaite Volcano, 2 –volcanic ash, 3 – lava flow, 4 – delta. The coastline before the eruption is an effect of vectorization of the Sentinel-2 imagery taken on 28.01.2021

Source: own elaboration based on Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem, https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/

At two-thirds of the distance from the crater, near the Volcanes de Aridane (4) , the lava cover splits into several streams. The southern branch advances broadly into the ocean, forming the larger of two deltas (42.7 ha). Meanwhile, the northern branch splits and rejoins, with only its northern branch reaching the ocean to create the smaller delta (4.6 ha) (5) . The lava volume comprising the basaltic cover is estimated at approximately 200 Mm3, with an average thickness of 12 m and a maximum thickness of 70 m (Carracedo et al. 2022, Chicharro Fermín 2022, Dóniz-Páez et al. 2024).

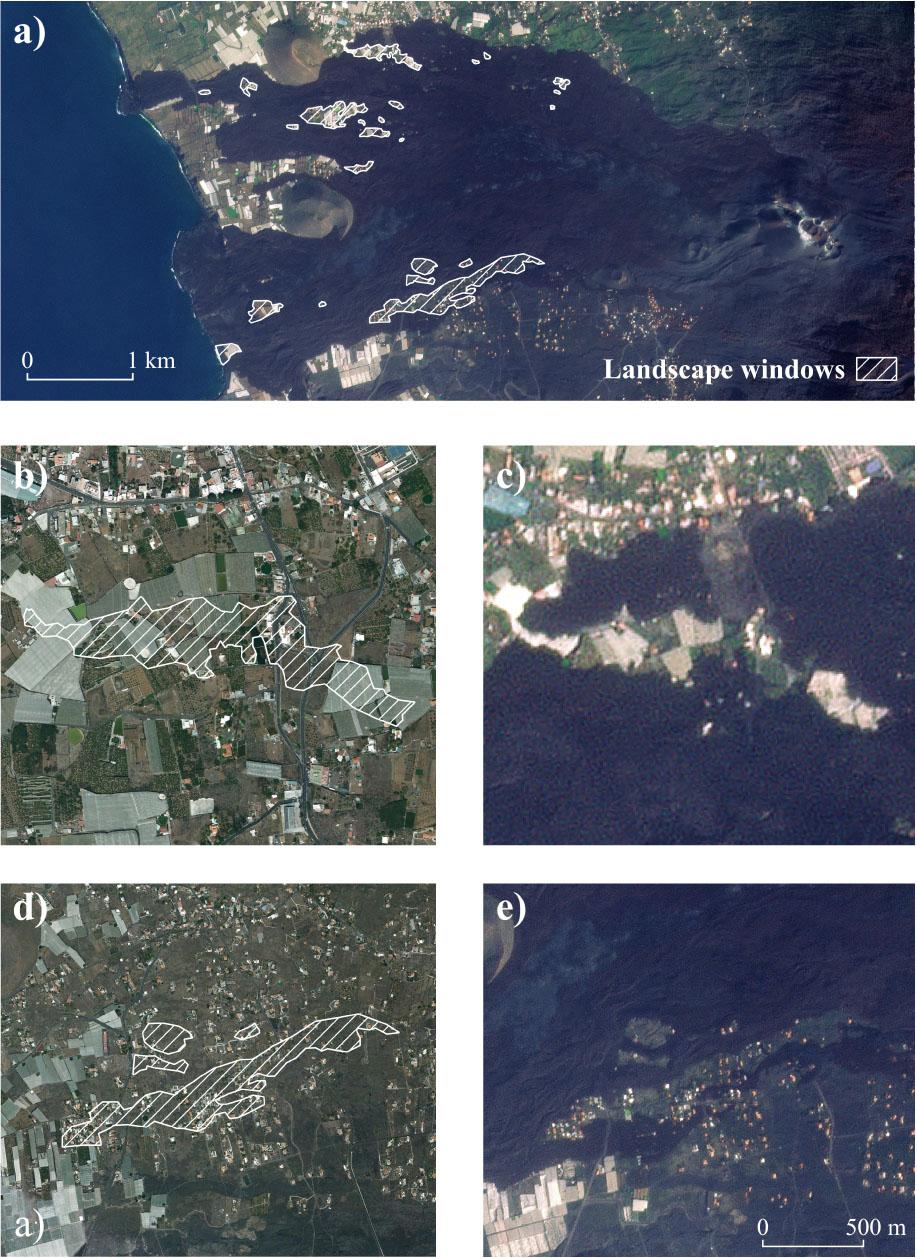

The young lava cover is discontinuous. Satellite imagery shows peculiar ‘windows’ of varying sizes and shapes, referred to as ‘landscape windows’. These expose unburied landscapes, barely visible from ground level and, as of May 2023, are still inaccessible for direct observation. To enhance the visualization of these landscape windows, high-resolution World Imagery satellite data from Environmental Systems Research Institute (ESRI) (Fig. 8) and PlanetScope satellite imagery for the post-eruption period were used. The largest landscape windows were detected in the southern part of the study area. Meanwhile, two smaller areas with minor landscape windows were located in the northern section. Satellite images also showed small landscape windows near the Tajogaite volcanic cone and close to the coastline.

a) – all landscape windows located within the area of interest, b) – first example of landscape window before the eruption, c) – after the eruption, d) – second example before the eruption and e) – after the eruption

Source: own elaboration based on the maps: ESRI World Imagery, DigitalGlobe, GeoEye, i-cubed, USDA FSA, USGS, AEX, Getmapping, Aerogrid, IGN, IGP, swisstopo, and the GIS User Community, Planet Labs PBC. [27 June 2024]

A key landscape transformation, which at times was as striking as the young lava cover, was the formation of a pyroclastic material layer. This layer, varying in thickness and composition, ranging from volcanic bombs, lapilli, and volcanic sands to ashes, overlaid and reshaped the existing landforms. Volcanic dust was carried beyond the study area. This layer accumulated on the terrain and, from a geomorphological perspective, contributed to landscape rejuvenation. Volcanic ash fallout from Tajogaite, ejected into the atmosphere, was recorded across almost the entire island of La Palma and Tenerife, Gomera and Hierro. However, substantial thicknesses of ash, locally reaching approximately 2 m, were observed only on La Palma. The volume of volcanic ash deposited on La Palma was estimated to be approximately 45 Mm3 (Carracedo et al. 2022, Chicharro Fermín 2022).

All the young landforms created by the Tajogaite eruption have been undergoing dynamic transformations since the eruption ended. These processes diversify the landscapes and give them distinctive features. Composed primarily of weakly consolidated pyroclastic materials, the volcanic cone has developed fissures and visible landslides that can be seen from a distance. The surface of the lava cover is also changing and as it cools, it cracks, subsides and fragments. Cavities and the roofs of lava tunnels are collapsing. Along the coastline, where new land was formed, beaches are emerging in place of those buried under lava. Subsidence is also visible in the pyroclastic deposit layer.

The fall of volcanic bombs and lapilli showers caused damage to the vegetation on Cumbre Vieja, which primarily consists of open pine forests dominated by the Canary Island pine (Pinus canariensis) (Fig. 9) and patches of matorral shrubland growing on historical lava flows and pyroclastic deposits. Although these plants, especially the pines, are known for their fire resistance and ability to regenerate, the natural vegetation has been severely impacted by the eruption.

Pinus canariensis forests damaged by pyroclastic showers on the Cumbre Vieja ridge

Source: photo taken by J.L. García Rodríguez

Contemporary cultural landscapes being buried under layers of lava and pyroclastic materials over an area of several square kilometres was devastating. Entire settlements were destroyed, including nearly 3,000 homes, schools, churches, cemeteries, roads, streets, power grids, water intakes, water supply systems and sewage networks (Llaneras, Borja & Vega 2021). Cultivated crop plantations were also obliterated (Hernández 2023), along with their complex irrigation systems, including water reservoirs, canals and pipelines. The emergence of a ‘new’ landscape resembling a natural (primary) landscape is a measure of the cultural landscape transformations observed during field research on La Palma.

However, remnants of degraded plantations, cracked and partially buried homes, ruined solar panels, and impassable roads blocked by lava flows remain along the edges of the solidified lava and volcanic ash cover (Fig. 5). Occasionally, these remnants form ‘landscape windows’ (Fig. 10–11). Nowhere else is the stratigraphy of the landscape as visible as here, at the site of the volcanic disaster on the slopes of Cumbre Vieja.

“Landscape windows” in the form of remnants of the previous settlement and agricultural landscapes

Source: photos taken by Authors and by R.U. Gosálvez (Fig. 11)

In the remaining areas, substantial degradation of cultural landscapes is evident. For buildings, the accumulation of large amounts of lapilli and volcanic ash on rooftops often led to the collapse of structures or severe damage to their integrity (6) . Within a radius of 1,500 m from the active crater, an area of approximately 7 km2, the fallout of ash, lapilli and volcanic bombs was so intense that it caused severe crop destruction, including vineyards (Fig. 12), banana plantations (Fig. 13) and avocado groves. This devastation unfolded before the eyes of their owners, as described in their poignant accounts (7) . Approximately 210 ha of banana plantations, 60 ha of avocado crops, 55 ha of vineyards and 40 ha of vegetable farms were devastated (Hernández 2023). An additional equivalent area was partially buried or damaged. Beyond physical damage to the plants, protective nets often stretched over banana plantations were also destroyed (Fig. 14). Around 75 km of irrigation pipes were damaged, and water reservoirs used for irrigation with a capacity of approximately 0.5 million m3 were lost (Llaneras, Borja & Vega 2021).

A vineyard covered by volcanic ash, May 9, 2023

Source: photos taken by Authors

A solidified lava flow flooding a banana plantation, May 8, 2023

Source: photos taken by Authors

Protective nets over the banana plantations damaged by volcanic ash

Source: photo taken by J. Dóniz-Páez

In the available literature on the aftermath of the Tajogaite eruption, the absence of a landscape perspective is striking. While there has been extensive research on volcanology and geophysics, geographical publications have predominantly focused on the socio-economic impacts of the eruption (Rodríguez Pérez 2023), with the eruption itself providing the backdrop for these discussions. Several publications discuss the potential for using the ‘new’ volcano and the extensive field of solidified lava as elements of natural heritage to promote geotourism, such as Dóniz-Paéz et al. (2023), Rodríguez Pérez (2023). However, no theoretical publications have been found that explore various possible methodological approaches to classifying newly formed or heavily volcano-altered landscapes. While global literature offers classifications of highly transformed landscapes, they are generally unrelated to volcanic eruptions (Myga-Piątek 2012; Antrop & Van Eetvelde 2017; Degórska & Degórski 2019).

The concept of landscape stratigraphy (Myga-Piątek 2018) can form a valuable framework for analysis. This was one of the perspectives adopted by the authors of this study. The landscape transformations on the western slopes of the Cumbre Vieja volcanic range observed during field research exemplify the stratigraphic model of the landscape.

A justified and convenient perspective has been the analysis of the natural determinants of cultural landscapes, for which numerous examples can be found in the Canary Islands, Cape Verde and the Azores (Makowski & Miętkiewska-Brynda 2020). The infrequent exploration of such topics might be because of the diverse ways in which landscapes are studied, as reflected in the extensive global literature: Solon (2008), Howard (2011), Farina (2012), Myga-Piątek (2012), Degórski et al. (2014), Antrop & Van Eetvelde (2017) and Degórska & Degórski (2019).

Concepts that diminish the importance of nature in anthropogenic (cultural) landscapes, as seen in studies by Pietraszko (2012) and Kamińska (2014), could be considered misleading or even overly radical in the context of La Palma. For inhabited volcanic islands, incorporating the natural context is crucial, as demonstrated by analyzing these relationships in Vanuatu (Bonnemaison 1974), Réunion (Bouchet & Gay 1998, ed. Jauze 2011), Hawaii (Huetz de Lemps 2003), the Galapagos (Collin-Delavaud 1989), and São Tomé (Gallet 2001). In this context, it is worth examining the history of Montserrat, which was affected by a substantial eruption in the late 20th century (Montserrat. First Report 1997). National atlases of French overseas departments, including the volcanically active islands of Réunion (1975) and Martinique (1977), offer a wealth of data and interpretations. The depth of nature–human relationships on islands has been examined in nearly all works by Doumenge (1966, 1987). For the Pacific islands, this approach is reflected in the works of Crocombe (2001). These researchers often, perhaps unconsciously, referenced analyses now termed the landscape approach. While human activity is often seen as the dominant factor in landscape transformation, that is, industrialization, urbanization and agricultural intensification (Antrop & Van Eetvelde 2017), the influence of natural processes, especially extreme events like volcanic eruptions, cannot be overlooked. This is a concept that has been evident at least since the time of G. Cuvier (Grabowska 1983).

As current satellite imagery confirms, it is hard to overlook, that in the area affected by the volcanic eruption on La Palma, human efforts to reclaim lost areas, such as building roads, power lines, reconstructing houses, establishing the foundations of plantations and constructing irrigation systems taming and restoring the cultural landscape, are almost as rapid as the forces of nature. The pace and intensity of these transformations are striking.

The consequences of the Tajogaite eruption differed between the volcanic ridge of Cumbre Vieja and the medianías region. Here, settlements were established, banana and avocado plantations introduced and vineyards have long been cultivated. In the case of Cumbre Vieja, one can speak of natural landscapes, where the volcanic eruption did not disrupt their continuity or evolution. At most, it rejuvenated these landscapes and postponed the advancing succession of vegetation or, more broadly, ecological succession. This process occurs in the underwater parts of the newly formed lava deltas on the western coast of La Palma (Botmar-ULL 2022).

The substantial landscape changes from volcanic eruptions, especially in terrestrial and likely underwater landscapes, represent a reversal of the geological clock. This results in a return to primitive landscapes, replacing those that are either close to natural or, more strongly, cultural landscapes. This shift creates an opportunity for natural succession, a process in which organisms colonize untouched land, potentially leading to the regeneration of natural ecosystems through the restorative power of forces of nature.

This is applicable to the cultural landscapes of La Palma, with perennial crops such as banana plantations, fruit trees including avocados, and vineyards as examples. All plantations in the path of the advancing lava flows were inundated. Similarly, grey infrastructure that was part of the cultural landscape, such as houses, roads, solar panels, power networks, water reservoirs, irrigation systems, and sewerage, suffered extensive damage or destruction, replaced by fields of lava. Once shaped by various elements and built on older lava layers from previous eruptions, the cultural landscape was buried under lava deposits ranging from several to dozens of metres thick, effectively erasing it.

In the case of anthropogenic (cultural) landscapes, which dominate the medianías zone on the western slopes of Cumbre Vieja and were shaped over generations on old lava and volcanic ash deposits, the volcanic eruption abruptly interrupted their continuity and slow evolution. The lava flows and ash deposits caused extensive destruction, if not total devastation, of the existing landscape, creating a new layer of landscape on top of the ruins. This new layer resembles a primordial landscape, evoking a state before human influence. This buried landscape can still be observed in ‘landscape windows’ preserved in various locations within the young lava and pyroclastic covers. This landscape transformation could be witnessed in real time on television screens.

The La Palma residents have not accepted the loss of their place on Earth. Roads are being built across the young lava cover, and new plantations are being established. This marks the creation of a new cultural landscape layer. It is forming on top of the young volcanic rocks, several, dozens or tens of metres above the layer of the cultural landscape that was destroyed. In the available satellite images, the cultural landscape ‘in statu nascendi’ can already be seen.

The medianías is an altitudinal zone between 600 and 1,500 m above sea level, characterized by extensive flat areas (llanos). It forms an intermediate zone between the highly diverse coastal belt (costa), featuring high cliffs and coastal plains with beaches, and the mountainous zone (cumbre), represented by the volcanic ridge of Cumbre Vieja.

CVVR – Cumbre Vieja Volcanic. The rift extends in a N–S direction, measuring approximately 20 km in length and reaching an elevation of around 1,950 meters above sea level. The rift zone covers an area of about 220 km2 (Dóniz-Páez et al. 2022). Its activity began approximately 125,000 years ago (Dóniz-Páez et al. 2023).

RGB – red, green, blue primary color model

Volcanes de Aridane – a meridional chain of four Quaternary volcanic cones running parallel to the coastline. From north to south, they are: Argual, Triana, La Laguna, and Todoque, located at the base of the slopes of Cumbre Vieja. Today, this area is designated as a natural monument (Monumento Natural de los Volcanes de Aridane).

Results of measurements from the imagery (Fig. 7). Similar values have been reported by Diaz Lorenzo (2024).

At a density of 1.2 to 1.40 g/cm3 (measurement of samples in the soil science laboratory of the Faculty of Geography and Regional Studies, University of Warsaw).

..the tragedy began stealthily. ‘The ash initially seemed harmless, and we never thought about the immense damage it would cause. We could never have imagined that something so seemingly innocuous could so thoroughly destroy the lives of the Palmeros’, said Juan Garcia Rodriguez, a banana plantation worker, as quoted in Crespo Garay (2021).