This study explored the impact of the Contaminated Blood Scandal (CBS) on the siblings and children of those Infected; it aimed to create a narrative answer to what the impact was on their lives, and how it has affected trust and interaction with healthcare. Although some evidence has emerged that has demonstrated the personal impact, none has previously shown the consequences of that in relation to their continued need to engage with healthcare, including specialist services.

The Contaminated Blood Scandal (CBS) was a worldwide event that infected many people, including people with haemophilia (PwH), with blood-borne diseases [1]. This has had a significant psychological, physical and financial impact on the families involved. Although some studies have focused on those directly affected, very little is known about the inter-generational impact. Many adult children of those PwH who were affected experienced the CBS during their formative years as relatives became unwell or died. Some may have lost both parents during this period, as many partners of PwH also contracted the diseases. During the period of loss and dying, the children of those infected experienced isolation and stigma, alongside grief and loss, both from society and healthcare professionals (HCPs) [2].

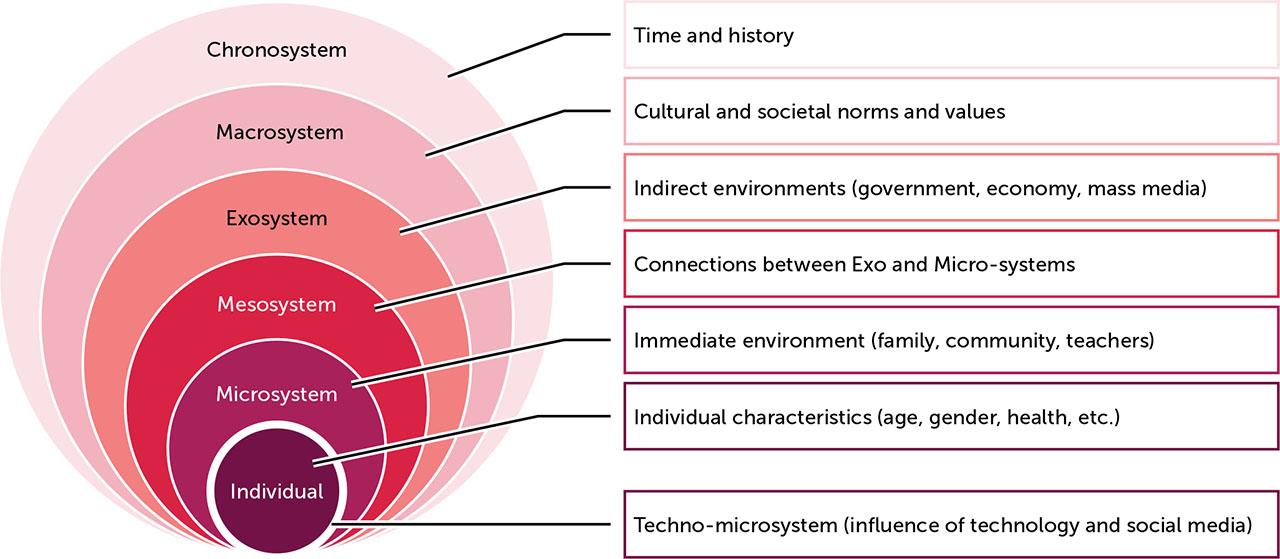

The experience of the CBS has impacted the children and siblings of those infected (referred to as ‘affected’). Decreased educational attainment in early life, increased mental health challenges, and risks of substance misuse are amongst the outcomes identified through the Infected Blood Inquiry’s expert reports [2]. Compounding that effect is the ongoing discovery of information for the affected in the haemophilia community, where new discoveries reopen barely healed wounds. Whilst little is known about the impact of the CBS on women who carry the haemophilia gene in relation to their choices around reproduction and potential continued interactions with haemophilia centres, a considerable amount of literature has been published on the impact of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and early childhood trauma. ACEs are well established as factors which increase risks of negative outcomes such as poor health, educational struggles, dysfunctional relationships, reduced earning potential and reduced opportunities. Although they have been criticised for being reductionist, deterministic and non-generalisable [3,4,5], recent studies demonstrate the risks associated with increased traumatic experiences as a child [6,7,8]. Developments such as the context and impact of the exposures [4], stigma and power [9], and a more nuanced approach to the parental role [10] have also been considered. Awareness and understanding of ACEs can provide a way to work with the family and an opportunity to break intergenerational trauma chains. To fully understand the experiences of this cohort of people, their experiences need to be placed in the cultural and political context of the time. In this work, we consider ACEs through the Bio-Ecological Systems Framework (B-ESF) (Figure 1), which includes the interactions and synthesis between individuals, environments and culture [11,12].

B-ESF theory places the individual within four systems (micro, meso, exo and macro) that have potential influences on their lifespan. Bronfenbrenner [13] emphasised the interactions between these system levels, and the impact on the development of the individual, noting that the person was included as an active participant with power. In applying B-ESF theory here, we draw into the narrative the broader context of the time and situation for the study participants, illustrating how these factors have played a part in their development. We include HCPs as elements within the microsystem and the specialist centres and patient organisations as part of the mesosystem. When these mesosystems interact with governmental, organisations and media systems, they form the exosystem, which the individuals do not interact with directly but which influenced their lifespan. The chronosystem is a key factor, placing the movement of the individual before, after and during the CBS, through an era where AIDs and HIV emerged as unknown and became linked with stigma and fear. In this way, all the levels interact with the potential lifespan for the individual, but in different ways.

Parental trauma has been shown to increase the risk of intergenerational transmission of trauma, passing the same challenges from parent to child [7]. Frosh [14] framed this well, stating, “It is not as if the historical damage lies silent, put to rest. It reverberates, keeps coming back, needs addressing in each generation as if it an implacable ghost, however much one tries either to resolve it or escape from it” (p. 261). Nasar and Schaffer [15] note that trauma is a “double wound” that touches the mind and body, taking time and space to heal. The impact of disasters on families and communities finds that loss and unresolved grief can be the foundation for 3–5 generations to recover healthy patterns of relationship [16]. Similarly to work by Danieli [17], the post-trauma adaptational style influenced the second generations perceptions of themselves - they refer to it as the “trauma after the trauma”, where the way others respond (societal indifference, avoidance and denial of their experiences) creates an impact known as a “conspiracy of silence” [17], “third traumatic sequence [18] or the “second wound” [19]. The family loss influences the way the family interacts, leaving them in a limbo, which is worsened when this happens in multiple families in a community and where the professional response is experienced as rejecting that reality, resulting in repeated, compounded trauma. This can be seen in the B-ESF, in the destruction of the immediate environment, from family, school to community.

This is a qualitative research study, using an interpretivist approach [20], conducted amongst the affected within the haemophilia community, by a researcher with member status, where the primary researcher is part of the group being researched [21]. The researcher’s member status was related to being born into the group, as a woman with the haemophilia gene and with a parent who was infected by the CBS [22]. Due to the likely impact on the research, the researcher used autoethnographic methods to maintain a high level of reflexivity [23], which allowed exploration of the acknowledged bias and personal reactions throughout. Autoethnography is the writing of the self, combined with the art and science of presenting experiences, beliefs or practices. It is a reflexive methodology that has a broad style and application, where the resulting work can provide powerful illustrations of personal experience or insights [24]. It embraces the positionality and subjectivity of the researcher, acknowledging the person fully as a research tool and as a research product [25]. It can stand alone but in this case is combined to examine cultural phenomena through several different lenses.

Ethics were a major consideration for this study, including maintaining confidentiality, balancing power dynamics, and recruitment choices. Relational ethics are a key element in autoethnographic methodologies and consider the right to publicly tell the stories of others involved in the narrative [26]. It was vital that consent to share the stories of others was sought at every stage. As an ‘insider researcher’, delicate balancing of contact with participants was a consideration; for example, when attending the Infected Blood Inquiry, it was made clear to participants that, if we met in person in a public location, they needed to acknowledge me first, to avoid removing the risk of accidental unmasking by the researcher. Equally, the researcher was entitled to join closed Facebook groups but choose to declare researcher status and promise to exclude their discussions from research before doing so.

There is a tension around what the researcher chose to disclose and conceal, and whether reasons for that concealment can be justified [26]. This balance in relational ethics is common within autoethnography, and Ellis [26] centres “mutual respect, dignity, and connectedness” in relation to the participants and communities we live in. In the current study, the researcher drew a line in disclosure: the stories of my family, their experiences and feelings are not included within the research unless they have given expressed permission to do so. I continue to follow guidelines by Ellis in considering my “responsibilities to intimate others who are characters in the stories we tell about our lives” [27].

This study has received ethical approval by the Research Ethics Committee at the University of Gloucestershire. (SREC.23.19.1).

Participants were recruited through social media. The criteria were that they were a family member of a person with haemophilia (PwH), either a child of an infected parent or a sibling of an infected child. The study did not originally include siblings but this was revised to recognise the complexities of the families involved. The impact of participating in the study were also taken into account. The interviews and transcripts produced hold a mirror up to the participant, enabling them to see a different version of their own story, which has unearthed emotional responses (and continues to do so); equally, they may experience cathartic effects [28]. Therefore, we considered the impact and risks of iatrogenic harm and curated resources for further support, which were given to the participants.

Participants took part in interviews with the researcher, focusing on the impact of the CBS, including effects on trust in healthcare professionals and engagement with healthcare services, and how individual, family, community, and societal factors interacted to influence development and trauma transmission across generations. The interviews were conducted at a place of their choosing with a semi-structured interview guide. They were digitally recorded and transcribed.

The transcripts were checked for accuracy by the researcher before being sent to the participants for checking. Nordstrom [29] referred to transcripts as “contestable performances” and suggests that existing in the space that they produce as they unwind results in a dynamic where those involved in the conversation “become in those spaces” to produce knowledge and narrative. Barad [30] (p. 178) noted that “We are responsible for the cuts that we help enact not because we do the choosing (neither do we escape responsibility because ‘we’ are ‘chosen’ by them), but because we are an agential part of the material becoming of the universe”. For the participants, checking their transcript was a key state in this process, providing them an opportunity to amend or add to their statements, but also to identify any elements that might risk exposing their identity. During this process, some participants worked with the researcher to make changes to the material facts of their situations (biographical details), but not to the meaningful experiences they shared. For this reason, none of the quotes are linked to specific participants.

The data was analysed using a deductive, six-stage process of Reflective Thematic Analysis, in NVIVO, to allow the telling of stories and creating a truth, rather than finding themes that are hidden within the data [31]. This mirrored the reflexive process of autoethnographic work, embracing the researcher’s role in interpreting the data, theoretical assumptions and the researcher themselves [32]. Transcribing the audio recordings allowed full immersion in the data to allow patterns, themes, and connections to be identified [31].

The study forms part of a PhD by published works undertaken by the lead researcher and supervised by LB and RJ.

Thirteen participants were interviewed for this study. Table 1 illustrates the relationships of the participants to the infected person, their gender, and whether they have genetic inheritance, to enable understanding of their perspectives.

Participant demographics (N=13)

| FEMALE (NO GENE) | FEMALE (GENE) WITH CHILD WITH HAEMOPHILIA | FEMALE (GENE) WITHOUT CHILD WITH HAEMOPHILIA | MALE (PWH) | MALE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | |

| Sibling | 1 | 1 | 1 |

PwH: person with haemophilia

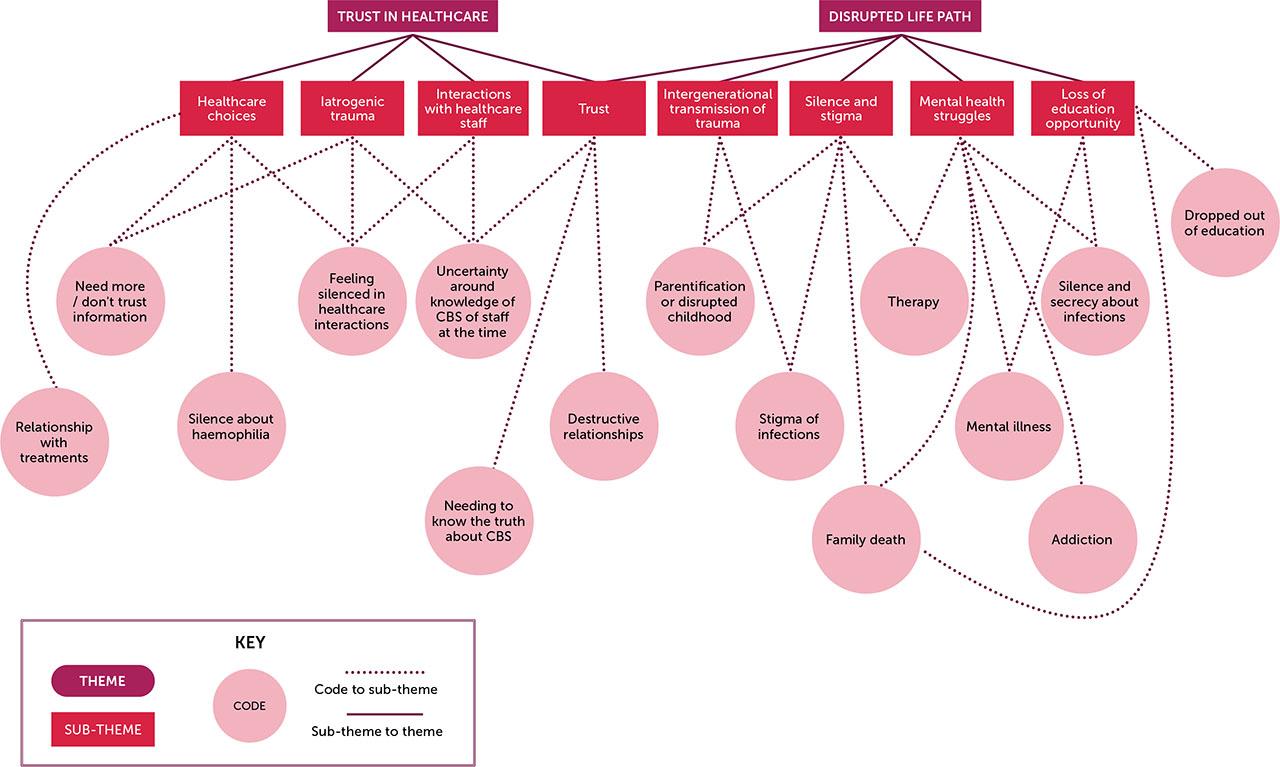

The themes that emerged are presented here, along with an exploration of their narrative in context of their situation. The themes included silence and stigma, mental health, education, inter-generational transmission of trauma, and reproductive and healthcare choices (Figure 2). Each theme will be explored in more depth, but all participants had experienced detours or destruction of their life paths. These frequently involved clear signs of emotional distress in the form of mental health challenges and struggles with addiction. Educational opportunities were lost, resulting in lower self-esteem and reduced socioeconomic status. The relationships in childhood affected their relationship choices and ability to form healthy attachments. The damage to trust in healthcare and other organisations was marked.

Reflective thematic analysis codes and themes

Strong themes of silencing and secrecy ran through all the participant interviews, with many referring to the risks of stigma and consequences. Although the two themes blended internal family behaviours and external factors, they illustrate an impactful narrative of isolation, beginning in childhood. Many of those who have established relationships in adulthood continue to silence themselves, with a significant number of participants speaking about their experiences for the first time during our interviews; some reported never speaking about the CBS with their partner or family. This is a common behaviour after loss and trauma, where families, society and others collude to avoid speaking about events, thereby decreasing connections between families and communities [33]. The stigma related to the infections impacted participants’ ability to seek support as children, excluding the usual sources of friends and school to protect the family:

“’You don’t tell your friends, and this is what you can and can’t tell them.’ I’m not angry with my mom and dad for that. That was just their way of protecting us as a family unit.”

As young adults, some felt that it was vital to hide their treatment from others, as the link between haemophilia and the infections was being made in the press:

“If they ever started to link the medicine to viruses, then we were in trouble. They would know and everyone else so… It was almost like the haemophilia had become a secret as a result of the exposure to the viruses because it was a gateway to the viruses... Oh, yeah, it was bloody awful. It was bloody awful.”

It was clear that families were managing this issue as well as possible, considering the risks of disclosure. To protect children, some parents hid their infection and health issues from them:

“They hid everything really well from me. There were lots of pill bottles with labels removed, I remember that.” “I felt quite excluded from what was happening in the family for a long time. And I…it wasn’t sort of, I don’t think my parents deliberately said, ‘We don’t want her involved.’ It was, you know, there’s an element of protecting me, but they wouldn’t tell me stuff.”

The silence also existed between family members who were both experiencing infection, with one participant explaining that they avoided the topic because of their own coping mechanisms:

“We wouldn’t really talk about it. You know, it would be a dirty secret that we kept to ourselves...”

Another noted that the silence was so deep that they only discovered the diagnosis of a relative at the funeral at a young age:

“My childhood ended on that day because everything that I knew to be true, and all of a sudden it was almost like a jigsaw slotting together.”

Interestingly, this continued as a theme throughout their lives, with some participants self-silencing their own needs from their families, when faced with traumatic life events, to avoid adding to the burden. This had a major impact on their wellbeing:

“That meant years of suicide attempts and self-harm and drug use, and you know, very sexually promiscuous trying to regain some power, trying to regain something that had been taken and lost from me. But nobody saw the traumas and the things that I was doing, and I’ve hung myself, I have taken overdoses and even then, at the hospitals I was ridiculed and laughed at and made to feel less than, and nobody ever offered me help. No one ever spoke to me like a human.”

The increased experience of mental health and addiction issues experienced by the affected reflected the impact of their traumatic experiences, where ACEs often result in increased risks for both. These can be severe or long-lasting if the issues continue or includes multiple issues, as the CBS has over decades, the affected waiting for acknowledgement and justice [8]. Most participants experienced multiple family member traumatic deaths, poverty and social exclusion. Some experienced family unit breakdowns, where relationships were severed or harmed. This impact on psychophysiology created a fundamental change in the view of self, disrupting socioemotional development. Interactions between the number of ACEs and severity of insecure attachment formation can result in issues with resolution of past trauma, unresolved mourning and difficulty connecting with others [34]. This was compounded by the delayed justice and truth in this case, which slowed healing and mourning. The resulting challenges in building healthy, sustained relationships was identified by many of the participants.

“What it gave me was a life of isolation, and pain and self-sabotage. But I was really, really angry with life.” “It just hits you all over again and you think ‘Why am I feeling so, shit right now? Oh right, yeah.’ You just don’t feel like you get a chance to grieve properly or get any closure...”

The impact of therapy was an ongoing thread for some participants:

“No amount of therapy, no matter how many times I talk about it, will ever make amends for what they did to my dad; they murdered my dad. That’s the only way I can put it. They medically murdered my parent.” “It wasn’t till after he kind of passed away and I started therapy and everything, I kind of went back through it and looked through everything, and it was like if that hadn’t happened, none of that would have happened in my entire life. It’s kind of ruined my life.”

For the majority of participants, education was disrupted due to supporting family or their own mental health struggles. ACEs resulted in poorer health (including mental health), abusive relationships, and a higher level of addiction issues. For those now in the profession they aspire to in their younger years, progression was delayed between 5 and 15 years.

“I went off to university, didn’t cope with being away from my dad, having phone calls to say he was ill, driving back just to look after him and then driving back again. And in the end, I just thought I can’t do this. I need to be at home dad. So, it had massive impact on my life.” “I dropped out of university. I am, career-wise… years behind where I should be. So, I am not where I could be, should be, ought to be.” “You know, would I have gone to college, if I didn’t have to go to get a job? Would I have done any of that? Would I have been so lost in my own isolation and thoughts and traumas? I don’t know. I suppose nobody can answer that.”

This mirrors Houtepen, et al. [6] who found evidence that ACEs are linked with lower educational attainment and reduced health and health-related behaviours. The impact of family and socioeconomic context adds additional risks to existing ACEs, reflecting the microsystem area of the B-ESF. Interestingly, those without children with haemophilia experienced it slightly differently, identifying their experiences as a driver to succeed:

“Sort of the world continues to turn, and you just have to get on with things. Just thinking back on it now, it just seems so surreal. When I see opportunities presented themselves to me, I take them because I’m like, I don’t know how long we’re going to be around. My dad didn’t have these opportunities.” “The first thing I did when my dad passed away was apply for uni and I was like, right, I’m just going. to take the power or strength he had and use it for something positive, and I sort of take that outlook and think, well, if my dad can do everything he can do, he did and got through, I can do this, I can get through this.”

Landau and Saul [16] noted that families who experienced unresolved grief and unexpected loss often took three to five generations to resolve the adaptive patterns of behaviour that were originally needed to cope. They identified that the culmination of transitions and changes to the family life cycle resulted in early self-reliance and parentification for children, especially when losing both parents or multiple significant family members. The resulting ACEs that many of the affected experience compound this impact further; the participants were highly aware of their own trauma, and the impact of that.

“We’ve been damaged in a way I think that’s a little bit irretrievable. So, I think they are insulting our integrity at the moment and I think I would just like for them to treat us with a bit more of integrity, a bit of honesty, and to treat us like human beings than lab rats, because they just keep kicking the can down the road.” “But I’m just scared that I’m damaging my boys that… But I know that my son’s anxiety comes from a place of worrying about his brother and that comes from a place of watching me worry about him… no. So, I’m very aware of the damage that I’m inadvertently doing.”

All of those with children or who had been pregnant expressed a link between their feelings around the treating teams and the mistrust they felt, related to their experiences of the CBS. However, one illustrated clearly that the impact had been passed to her children, despite her attempts to conceal and move on from the trauma.

“He [son] had a bleed. I remember going to the hospital and he said to me, ‘Why are you taking me somewhere where they couldn’t save granddad?’ and it killed me. I remember driving down the motorway sobbing, thinking I’m having to lie to my son because he’s absolutely right. I was having to not lie, but you’re having to do this whole ‘I trust these adults, you feel safe.’ You know… ‘It’s Doctor…we love Doctor because …you know he delivered your brother’ and …and yet couldn’t do the one thing which was in his eyes was looking after his number one hero.”

The fear of losing a family member was most strongly evidenced in one interview:

“He was young when my dad died. And I remember going to put the bins out and I come back in, and he was screaming, and I said, ‘Darling, what happened?’ He said, ‘I thought you come to granddad in heaven.’”

One participant summed up the transmission of inter-generational trauma very clearly in her discussion of its impact:

“It was all of us, all of us that was connected. Everybody that had a connection, that ripple effect that came out, even to our children and probably our children’s children. Because they won’t trust the NHS because they won’t trust doctors. By the time it gets to our children’s children, they probably won’t even know why. But that fear will still be there, that feeling will still be there, even if they don’t know where the roots of it came from.”

The specialist haemophilia centres’ power and influences during the CBS were strong elements of influence in the B-ESF, sitting in the mesosystem area. Additionally, prenatal care provided in the same locations triggered traumatic memories. The narratives of those involved in our study were directly linked to their fears around having a son, who would need treatment and experience (in their perception) the same risks of infection. In one case, the participant’s father’s pain at the point of gender reveal was traumatic to them over a decade later. Two participants had based their decisions not to have children on their experiences when young, and one hoped that his daughters would not have children at all.

“I really wanted another girl because I just thought, I don’t want to have to have this level of worry and it’s not even the haemophilia itself. I mean, it’s the bit that comes from my dad and being contaminated.” “I never wanted children, and I certainly do not want my children having children. But my girls are scared of having children as a result of me.”

There was a thread of shame for the female participants who felt this way. They strongly emphasised their love for their sons but said that they feared having a child with haemophilia, which compounded the guilt for their inheritance of haemophilia. Reactions from their fathers was highly impactful, alongside their own emotions and fears:

“[Dad] just begged me, ‘Don’t ever let him have blood products.’ We went to a shop and bought coloured clothes. And that’s how we told him. I found out it was another boy and I lay on the bed, and I sobbed and the lady doing the ultrasound was like, ‘Oh, it’d be great, you know, pillow fights and den building,’ and I look, just look at her and said, ‘You have got no idea.’ I went to the shop, and we bought a blue romper suit, and I gave it to my dad. He just threw it back at me and he went, ‘No, I can’t deal with this,’ and that’s not okay. You know, he should have been proud and excited.”

Many participants identified a great need to have information about the treatments their children may have or were receiving. The trust that a healthcare professional was providing the correct treatment was impacted:

“I shouldn’t have to second guess a medical professional. But I shouldn’t have to constantly say to them ‘What you’ve given them? Can I just check that vial please? Can you tell me where that’s coming from? Can you tell me where that’s manufactured? Can I go away and have a read of that please before I consent to anything?’”

Family members checked the literature to assess information, trusting in science over haemophilia centre staff:

“I’ve got him treatment and then I do silly things, like look up treatments which have been tested for adults but not for children because it’s not economically viable. Then I think, well, should I be giving it to him, because you know, and then you just start this internal anxiety just constantly. It just doesn’t go away. It’s just constant.”

Receiving new treatments was a concern for some participants, with frequent concerns around safety:

“To use a new treatment with this dark history would be something that troubled me, a choice I do not know if I were brave enough to make. To place trust in people like healthcare people, even if they were not there during the dark times, is a leap of faith I am not certain I have.”

The increased mistrust and unwillingness to engage with the specialist team in an authentic manner also extended to impact on acceptance of other healthcare, such as vaccines.

“I do remember often thinking how would I deal with that dilemma because I was too afraid of having blood products? But then, the more I thought about I thought absolutely didn’t trust anything the government was trying to roll out.”

Those without children were similarly impacted in both their own healthcare decisions and those of their family:

“We’re all very dubious when we do our research for everything. We’d ask all the questions that we need to ask. We wouldn’t just take them at face value.” “I’ve been very, very distrusting and I shouldn’t have to. You should be able to go into a hospital or wherever and know that you’re in safe hands. I don’t have that. If I can avoid it. I don’t go.”

Although medical consultants have been the primary focus of studies and commentaries so far, our participants mentioned the nursing and allied health staff. One participant noted that, although his family were avoiding healthcare, he had no concerns about trusting the professionals:

“I know some had big problems with hospitals and the like. I love the medical profession and so, I’ve got no qualms about going to hospital or going to a doctor’s appointment or what have you.”

However, staff dismissal of concerns was destructive in terms of trust:

“I feel we’ve got a very kind of old school nurse that runs the department. And she’s just like, all no nonsense like, ‘Oh no, this just would never happen.’ She just kind of tiptoes around me sometimes or just makes me feel like I’m being over the top, but I feel like you just need to understand the place that I’m coming from.”

Silencing or minimising by healthcare professionals was clearly resented:

“Tried to have any conversations with them before and it’s like a bring the conversation down. So, nobody sort of listens, ‘Let’s go and sit in this side room here,’ and in case somebody else listens.”

This was felt when decisions were being made around treatment for one participant’s child, and she asked for further information:

“I just found that the nurse for the haemophilia department was quite kind of matter of fact, ‘This is what we’ll do,’ and a bit dismissive.”

Those staff members who were not present or connected to the CBS inherited its consequences in the form of mistrust, starting in the prenatal stages, but have overcome it with compassionate, supportive interactions with the whole family:

“His haemophilia nurse is approachable. She’s honest with him. She listens to me and my husband. But if I need the emotional support, the TLC it’s there. I think a lot could be learned from watching the way that his haemophilia nurses is with him. She’s phenomenal. It’s that support for us as a family.”

Equally, being open and honest about specialist knowledge the staff did hold was vital in building that trust or destroying it:

“Can you pretend like I’m an actual human being with feelings? And if you don’t know about something, don’t pretend you do. It’s alright. I’m sure you have your specialties. But please don’t pretend like you do now.”

One participant expressed a desire for trauma informed care, with compassion:

“So, sensitivity understanding, awareness of the trauma that you know somebody like myself has experienced, that then having to deal with health professionals about yourself or you know about my son or any anybody that is close to it. Just having a level of patience and understanding and sensitivity and awareness and helpfulness, you know. Just a bit more reassuring, really.”

Having healthcare professionals act as allies and be willing to stand up for the truth was an ongoing theme:

“If you see wrong, say so, point it out and be proud of that. Don’t be part of the problem. Don’t close ranks around a lie and cover up for your colleagues. It’s despicable.”

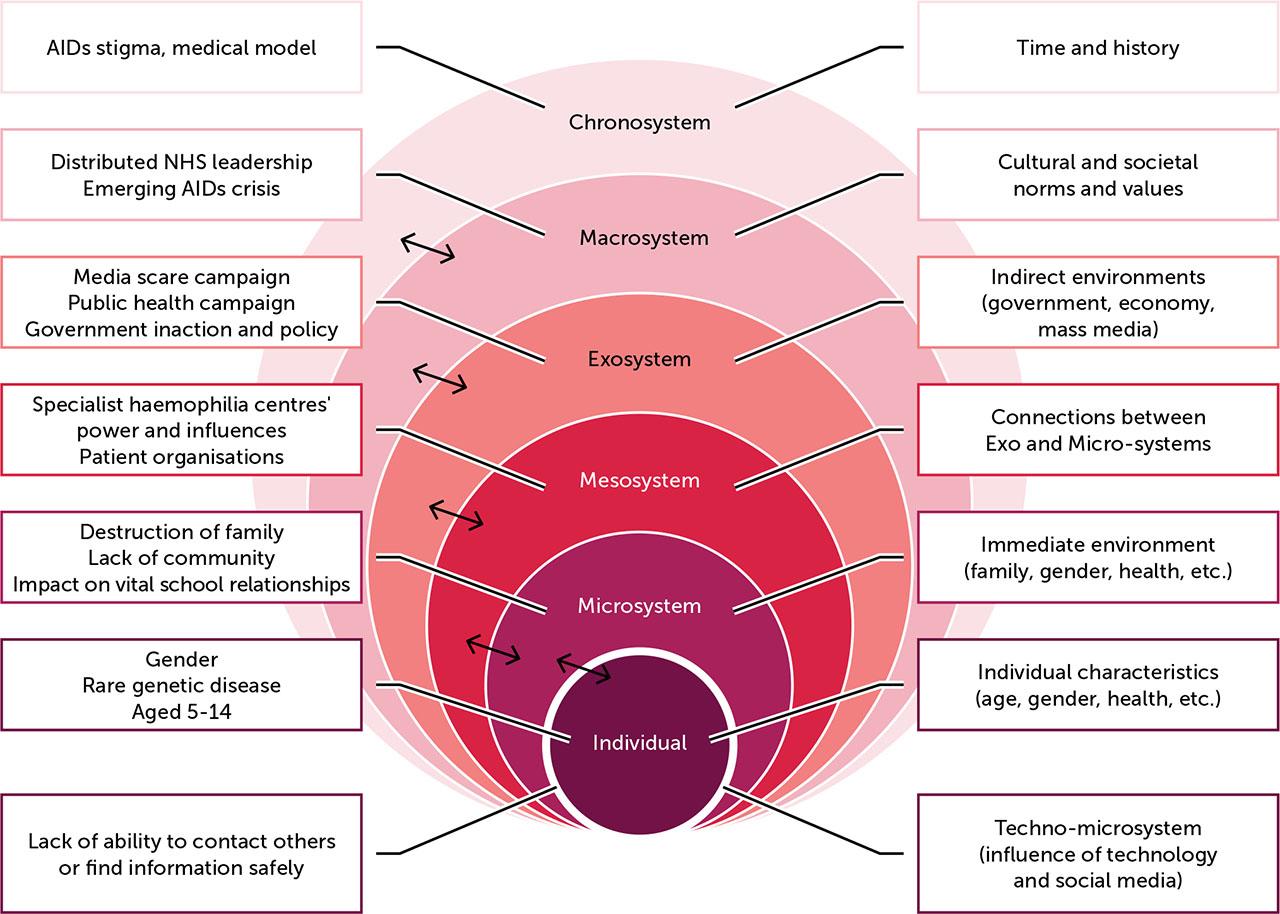

The intergenerational impact of the CBS was evidenced throughout the study interviews, with severe impacts on the lifepaths of the participants and continued trickle-down effects on their children. It affected their relationships to healthcare in general, and specialist healthcare professionals specifically. The Infected Blood Inquiry also impacted on their current well-being and mental health. These themes together create a picture of intergenerational trauma that has caused considerable harm to the families of those infected. It is evident that each level of the B-ESF model illustrates the continued harm (Figure 3).

Bio-Ecological Systems Framework (B-ESF) of the Contaminated Blood Scandal

The awareness of the impact on their lives was clear, with some participants using analogies of ripples through time. Many of them were hyper-aware of the silence they still felt they had to maintain, both personally and with specialist haemophilia centres. For mothers with children with haemophilia, this awareness compounded the guilt that they already experienced, worsened by the stigma experienced during the HIV/AIDS era [35]. That stigma had excluded them from local society, including isolating them at school and from their friends, leading to feelings of low self-worth and social withdrawal, learnt from those around them [36]. Children who were told to conceal a family member’s infection from everyone, or who observed actions to conceal the infection, were unable to seek support from others, including their friends or teachers, even when the restrictions were lifted. The inability to seek information or support safely was a major factor in creating the traumatic environment.

More recently, the Psychosocial Expert Reports to the Infected Blood Inquiry provided further illustration of the scope of inter-generational problems, including the urgent need to access psychological support. They highlighted the theme of reproductive choices that women carrying the haemophilia gene faced during the CBS, which is also noted by the women in our study [37]. Women being offered abortions or choosing not to have children were highlighted in both the report and our study, and PwH also had concerns about their daughters having children. Similarly, the report highlighted the increased risks of poor mental health and reduced educational outcomes, which our study demonstrates has had a significant impact on the lives of participants [37]. The supplementary report that focused on the impact of childhood bereavement also mirrors some of our findings, highlighting the complicated grief that the affected siblings and children experienced, and continue to experience [2]. They also noted the impact of stigma, derailment of life paths, the necessary parental choices on concealing or revealing the infection to them, and the silencing and secrecy. They discussed the difference in impact across genders, which may also be reflected by the choices of who came forward for our study.

The synthesis of the different levels of the B-ESF model becomes clear; each reinforced the impact of the others, with teachers, families and staff at specialist haemophilia centres working on the mesosystem level, interacting with the macrosystem’s stigma related to AIDS/HIV, power dynamics with the specialist centre national structures and governmental interaction. The media and public health campaigns interacted with the macrosystem, to feed the stigma and fear that impacted the children directly. The resulting lifespan impact, ACES and change in approaches to trust in healthcare and governmental systems and representatives emerged from this cascading effect, where each level reenforced the others.

These two questions cannot be separated in their answer. For the affected, the CBS is not in the past and its ripples continue to affect them and their children. The changes in expectations and needs in the relationship between families with haemophilia and specialist professionals are clearly supported by Fillion [38], who studied physician and patient interactions in the haemophilia community in France. Their reflections of the type and level of engagement and trust extended – from disengagement, where the person only seeks treatment when urgent and vital, to choosing to trust – was also noted in our study. Most participants trusted but verified; the reaction of the healthcare professional was key in building or reducing trust in that relationship; where compassion and family-entred care existed, trust was rebuilt, and where dismissal and silencing happened, mistrust increased. Participants identified needs for support that was individualised, holistic and has continuity, with empathic, well-informed clinicians. In some cases, they highlighted areas of quality practice that met these needs and in others they experienced behaviours that, whilst likely well-meaning, were experienced as silencing or dismissive.

The need for empathic listening and witnessing of trauma is reflected in work by Frosh [14]. In trauma-informed care, witnessing the trauma is a key action [39], whereas the opposite can retraumatise. In other words, failing to see and acknowledge the trauma makes a person equally as culpable because they offer hope that the pain will be recognised but fail to live up to that [14]. Speaking out against that silence was frequently the desired outcome from sharing the pain our participants experienced, even if the witness was not part of the CBS. Those deep memories cannot easily be healed due to the powerful experience of extreme suffering [40], nor can every moment of witness prevent retraumatisation. This study has demonstrated that empathy displayed by the staff member allowed the participant to regain elements of trust, and the opposite was shown where silencing or dismissal happened. South and Khair [41] identified that healthcare professionals over-estimate their influence; this study may illustrate some of the reasons that feed into that trust dynamic in the haemophilia community, since many of the participants concealed their fears from their healthcare team, continuing to self-silence and protect their children. This may also link to work by Keshavjee, et al. [40], who noted that, “The suffering of the haemophilia community is inextricably linked to a deep sense of betrayal by groups that were ostensibly their guardians: the physicians to whom they conceded their unmitigated trust” (p.1083). Their exploration reflected our study findings, demonstrating the impact on trust in healthcare workers.

The impact on other healthcare choices was another element that highlights the broader impact of the CBS on public health; for example, vaccine hesitancy for the wider family was mentioned by two participants. Given the increasing life span of PwH, this may become increasingly relevant as this generation begin to develop chronic conditions related to older age.

Trustworthiness of knowledge-based professionals is not uncommon in the theory base, where iatrogenic injury results from shifting blame onto the victim, placing the accountability onto the individual [36]. This perceived lack of accountability and trustworthiness was also extended to the wider healthcare system, governments and pharmaceutical companies, as participants placed hope in the Infected Blood Inquiry to bring them justice, knowledge and accountability. The continued delay in receiving this justice continues to build the cumulative trauma and mistrust. The power held by these organisations so strongly influenced the participants’ lifepaths that it is reflected throughout the B-ESF, where government inaction (including to this day), specialist haemophilia centres and patient organisations were actors in creating an environment of mistrust and fear.

Our study demonstrates the extent to which the CBS created a bio-ecological system that has fed into a fear of passing on the bias against healthcare professionals and heightened anxiety about treatments for their children.

The small sample size is not unusual for qualitative work but may have been influenced by the concurrent Infected Blood Inquiry. Some potential participants who did not participate in the study expressed that the emotional impact made this additional conversation too much. There are also those who do not engage in social media or with campaign groups who would not necessarily have been reached; however, word of mouth did result in contact from some. Recruitment sample boundaries were complicated by the multiple roles held by family members, i.e. a sibling of an infected person who was themselves infected was later included. Another issue that impacted on recruitment was wariness about involvement in research – for this reason, the word was avoided in the recruitment adverts.

The researcher’s insider status, whilst providing access and understanding, may have led to assumptions about shared meaning that external validation could challenge. Regular reflexive practices attempted to address this limitation, but the potential for interpretive bias remains. However the methodology’s strength lies in accessing narratives typically concealed from healthcare providers and other researchers.

Whilst some elements may have been identified previously, this is the first study to make the link between inter-generational trauma and the CBS and to demonstrate its powerful impact on trust in healthcare professionals. It is evident that ACEs for this generation of families with haemophilia requires trauma-informed care throughout the journey with specialist haemophilia centres. The inclusion of PwH and their families in the CBS has resulted in ongoing trauma, mental health issues, addiction, derailing of lives, and reduced trust in healthcare. Engagement with specialist healthcare carries a risk of retraumatisation, and medical decision-making is impacted across the health system. Understanding and anticipation of an increased informational need, higher levels of health anxiety, and a lower trust, both in the organisation and personal levels, are vital going forward. The retraumatisation of families is likely to continue the inheritance of the CBS, creating a cycle of harm that could be halted.

The life path of this group of people has been severely impacted, resulting in both psychological and socioeconomic disadvantage. This can further impact their children, thereby passing that on through the generations. By viewing this harm through the lens of the B-ESF, there is an opportunity to identify key elements that have potential to change, whether collectively or individually, for the families and for the future.

For the haemophilia community, the level of trauma they have experienced and continued to experience through silencing and denial has, for some, resulted in symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Early intervention and support is vital in reducing stigma and avoiding further retraumatisation. Throughout the study, participants stated a need for awareness of their traumatic past, of the changes to support that were meaningful to them, and the need for a level of control over management of symptoms. They highlighted a desire for the multi-disciplinary haemophilia care team to treat them with respect, giving them space and understanding, along with a heightened awareness of how phrases used in healthcare can be heard differently through the lens of their history. We call for further urgent work to explore the ways in which specialist haemophilia centres can meet this need, from contraception to the grave, centring the voices of people and families with haemophilia in that work. The lessons of the past and present should not be lost.