Peripheral artery disease (PAD) is a condition that affects the small- and medium-sized arteries of the limbs and is characterized by the progressive narrowing of the vessels due to atheromatous plaques.1 These modifications of the normal blood flow result in an inadequate supply of oxygen and nutrients to the cells, leading to symptoms such as intermittent claudication.2,3 This pathology primarily impacts older individuals (over 65 years), yet our clinical observations and the latest studies4 indicate an increasing trend of younger presenting with symptoms, some even before the age of 45 years.5 This can present a challenge for medical management, as younger patients have a longer life expectancy and need a more durable solution, with a faster recovery. According to the clinical examination and the Leriche classification, patients can present claudication during physical activity in stages I and II, pain at rest in stage III, and advanced trophic lesions in stage IV.1,5

Given the inflammatory mechanism underlying atherosclerotic plaque formation, recently there is a growing interest in evaluating the association between various inflammatory markers and the onset and progression of the disease.6 Danielsson et al.7 highlighted that diabetes mellitus accelerates the inflammatory processes in the vessel wall, as evidenced by elevated levels of interleukin-6 and white blood cells (WBCs) in patients with critical limb ischemia and diabetes mellitus. Additionally, recent findings by Mureșan et al.8 suggest a strong association between elevated systemic inflammatory markers and the presence of subclinical atherosclerosis in patients suffering from diabetic polyneuropathy. Therefore, we consider the leukocyte glycemic index (LGI) a conceptual framework to examine the impact of fluctuations in blood glucose levels on leukocytes, which are essential in regulating immune responses.9

Leukocytes, particularly neutrophils and monocytes, are highly sensitive to changes in blood glucose concentrations. Elevated glucose levels can initiate an enhanced inflammatory response, driving leukocyte activation and promoting the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines.7 Therefore, maintaining glucose homeostasis is essential in reducing leukocyte-mediated inflammation, which is key in preventing or managing conditions such as chronic inflammation, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic syndrome. 10 Taking into consideration all of the above, the aim of this study was to investigate the relevance of the LGI in the occurrence and evolution of PAD in patients younger than 45 years.

We performed a retrospective observational study in which we enrolled all patients under 45 years admitted to the Vascular Surgery Clinic of Târgu Mureș Country Emergency Hospital between January 2019 and May 2024. We excluded patients with vascular trauma, end-stage kidney disease (hospitalized for surgery on an arteriovenous fistula for dialysis), autoimmune conditions, sepsis, and those with missing data related to laboratory analyses, comorbidities, or risk factors in the hospital's electronic database. The included patients were divided into two groups, based on the presence or absence of systemic atherosclerosis. Systemic atherosclerotic lesions were defined as symptomatic atherosclerotic damage to the arteries of the lower limbs or carotid arteries.

We collected demographic data, comorbidities (hypertension, ischemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, cerebrovascular events, chronic renal disease, and diabetes mellitus), risk factors (active smoking, obesity, dyslipidemia), and routine laboratory analyses for all included patients, from the hospital's electronic database.

We also recorded cardiovascular (myocardial infarction) and cerebrovascular (transient vascular attack or stroke) events from the patient's history. We examined various systemic inflammatory biomarkers, such as the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), monocyte-tolymphocyte ratio (MLR), and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), which have been shown to have predictive value in vascular disease and other chronic diseases.5,11,12,13,14 The LGI was determined using the formula outlined in the literature: 6 (leukocyte count in 103/μl) multiplied by (glucose level in mg/dL) divided by 1,000.

The primary objective was to assess whether systemic inflammatory biomarkers such as the NLR, MLR, PLR, and LGI could be linked to the presence of symptomatic atherosclerotic disease in patients under 45 years of age.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for Mac OS v.28.0.1.0 (SPSS). The average age and laboratory data were reported as mean ± s.d. We used the chi-squared test to compare dichotomous variables between groups, and the Mann–Whitney and Student's t-tests to evaluate differences in continuous variables. Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve analysis was conducted to establish optimal cut-off values for LGI based on the Youden index, which ranges from 0 to 1 and is calculated using the formula Youden index = sensitivity + specificity − 1. All tests were two-tailed, with a p value of less than 0.05 considered statistically significant.

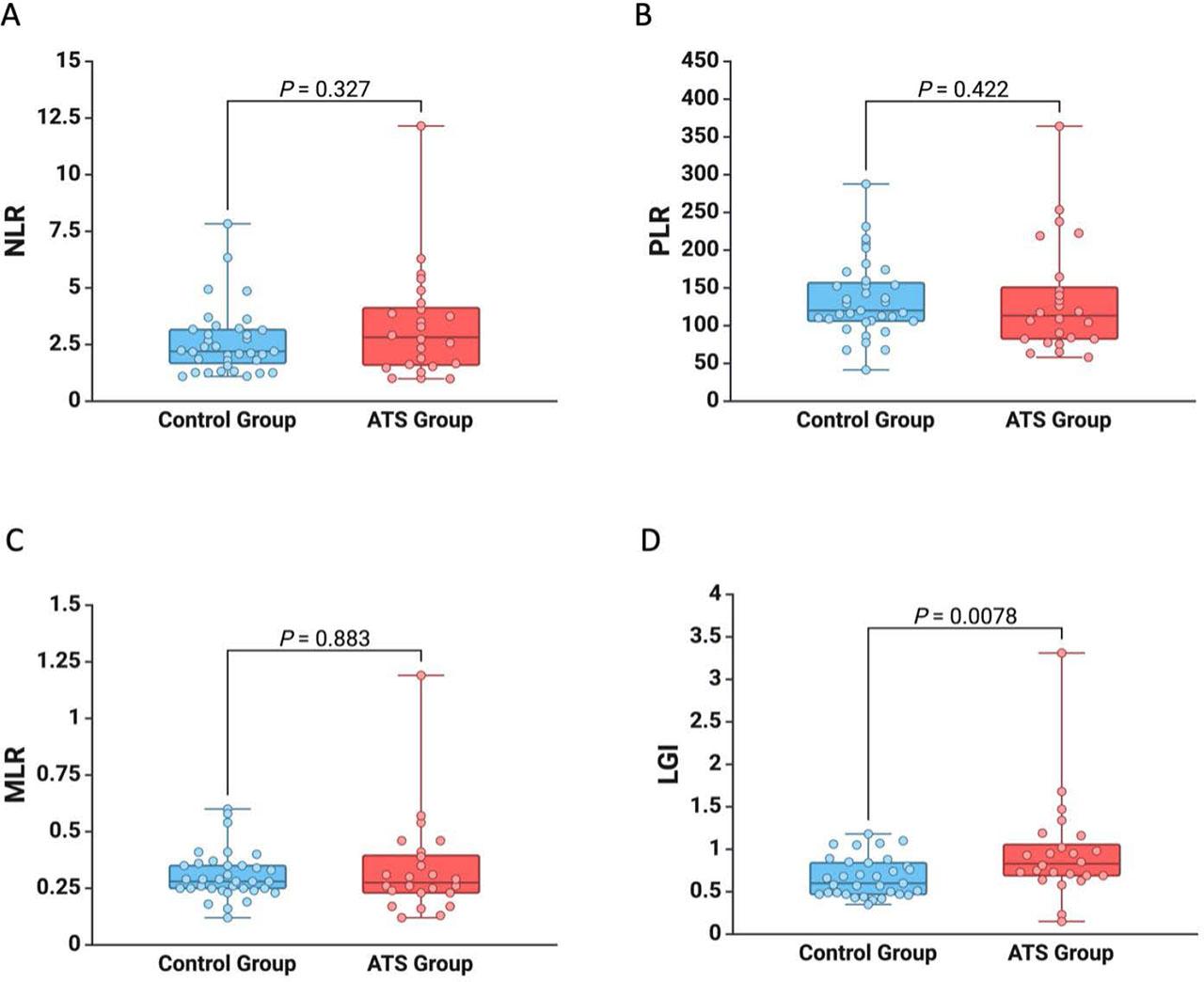

Our study involved 59 patients, divided into two groups: 34 patients without systemic atherosclerosis and 25 patients with systemic atherosclerosis. The mean age of patients was 37.19 ± 5.49 years, and 54.25% were men (Table 1). Following the analyses of comorbidities and risk factors, we observed that patients with systemic atherosclerosis disease had a higher incidence of ischemic heart disease (p = 0.038), cerebrovascular events (p < 0.001), and active smoking (p < 0.001) (Table 1). Regarding the laboratory data, in patients with systemic atherosclerosis, we observed higher values for WBCs (p = 0.003), platelets (p = 0.038), neutrophils (p = 0.002), monocytes (p = 0.024), and lymphocytes (p = 0.01) (Table 1). These patients also had higher values of the LGI (p = 0.006), but there was no difference between the groups regarding the NLR, MLR, and PLR (Figure 1).

Demographic data, comorbidities, risk factors, and laboratory data of the study population

| Variable | All patients (n = 59) | Without atherosclerosis (n = 34) | With atherosclerosis (n = 25) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± s.d. | 37.19 ± 5.49 | 35.68 ± 6.04 | 39.24 ± 3.88 | 0.007 |

| Male, n (%) | 32 (54.24%) | 17 (50%) | 15 (60%) | 0.446 |

| Comorbidities and risk factors, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 11 (18.64%) | 4 (11.76%) | 7 (28%) | 0.114 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 3 (5.08%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (12%) | 0.038 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1 (1.69%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) | 0.240 |

| Cerebrovascular events | 5 (8.47%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (20%) | 0.006 |

| Obesity | 5 (8.47%) | 3 (8.82%) | 2 (8%) | 0.911 |

| Active smoking | 27 (45.76%) | 7 (20.59%) | 20 (80%) | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 10 (16.95%) | 3 (8.82%) | 7 (28%) | 0.052 |

| Chronic renal disease | 2 (3.39%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (8%) | 0.093 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2 (3.39%) | 1 (2.94%) | 1 (4%) | 0.824 |

| Laboratory data, mean ± s.d. | ||||

| Red blood cells, × 106/μl | 4.64 ± 0.49 | 4.72 ± 0.52 | 4.54 ± 0.45 | 0.190 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 13.88 ± 1.67 | 14.00 ± 1.87 | 13.71 ± 1.38 | 0.416 |

| Hematocrit, % | 41.17 ± 4.43 | 41.63 ± 4.98 | 40.55 ± 3.56 | 0.244 |

| Platelets, × 103/μl | 260.65 ± 74.82 | 239.24 ± 52.44 | 289.78 ± 90.62 | 0.038 |

| WBCs, × 103/μl | 8.09 ± 2.82 | 7.31 ± 2.14 | 9.15 ± 3.30 | 0.003 |

| Neutrophils, × 103/μl | 5.50 ± 2.50 | 4.61 ± 1.89 | 6.7 ± 2.75 | 0.002 |

| Lymphocytes, × 103/μl | 2.15 ± 0.79 | 1.91 ± 0.53 | 2.46 ± 0.97 | 0.01 |

| Monocytes, × 103/μl | 0.63 ± 0.22 | 0.57 ± 0.18 | 0.70 ± 0.25 | 0.024 |

| Eosinophils, × 103/μl | 0.19 ± 0.23 | 0.16 ± 0.12 | 0.22 ± 0.32 | 0.429 |

| Basophiles, × 103/μl | 0.04 ± 0.02 | 0.05 ± 0.03 | 0.04 ± 0.02 | 0.889 |

| Na, mmol/l | 140.3 ± 2.34 | 140.61 ± 2.2 | 139.9 ± 2.5 | 0.211 |

| K, mmol/l | 4.39 ± 0.43 | 4.34 ± 0.28 | 4.45 ± 0.55 | 0.568 |

| Glucose, mg/dl | 98.5 ± 36.61 | 92.86 ± 14.54 | 105.72 ± 52.52 | 0.355 |

| BUN, mg/dl | 31.44 ± 22.21 | 28.78 ± 6.92 | 34.73 ± 32.41 | 0.347 |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 0.99 ± 1.5 | 0.82 ± 0.13 | 1.21 ± 2.27 | 0.231 |

| GFR, ml/min | 106.85 ± 23.05 | 104.49 ± 15.99 | 109.87 ± 29.88 | 0.228 |

| Quick time, s | 12.41 ± 1.3 | 12.27 ± 1.48 | 12.59 ± 1.03 | 0.118 |

| Prothrombin activity, % | 98.5 ± 19.53 | 100.11 ± 17.56 | 96.4 ± 22.07 | 0.298 |

| INR | 1.03 ± 0.11 | 1.02 ± 0.1 | 1.03 ± 0.12 | 0.530 |

| GOT, U/l | 27.02 ± 15.04 | 27.38 ± 13.92 | 26.66 ± 16.32 | 0.682 |

| GPT, U/l | 32.77 ± 27.98 | 33.66 ± 30.09 | 31.67 ± 25.8 | 0.977 |

BUN, blood urea nitrogen; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; GOT, glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase; GPT, glutamate-pyruvate transaminase; INR, international normalized ratio

Graphic representation of the difference between patients with systemic atherosclerosis and without systemic atherosclerosis for NLR (A), PLR (B), MLR (C), and LGI (D)

In the group of patients with atherosclerosis, six patients (24%) had carotid stenoses. Regarding the clinical stage of PAD, six patients (24%) were classified in stage IIA, five patients (20%) in stage IIB, three patients (12%) in stage III, and five patients (20%) in stage IV (Table 2).

Clinical stage of PAD among patients with systemic atherosclerosis

| Leriche Fontaine classification, n (%) | Systemic atherosclerosis group (n = 25) |

|---|---|

| Stage IIA | 6 (24%) |

| Stage IIB | 5 (20%) |

| Stage III | 3 (12%) |

| Stage IV | 5 (20%) |

| Carotid stenosis | 6 (24%) |

In the ROC analysis, we observed a significant correlation between the baseline values of LGI and systemic atherosclerosis (p = 0.004). The area under the curve (AUC) was determined to be 0.707, with an optimal cut-off value established at 0.683, resulting in a sensitivity of 79.2% and a specificity of 60.6% (Figure 2).

ROC curve analysis for LGI regarding the presence of systemic atherosclerosis

Furthermore, the logistic regression analysis revealed that age (OR 2.07; p = 0.021) and active smoking (OR 4.39; p = 0.049) are significant predictive factors for the presence of systemic atherosclerosis in young patients (Table 3). Additionally, elevated baseline values for platelets (OR 2.18, p = 0.017), WBCs (OR 2.06; p = 0.020), neutrophils (OR 2.75; p = 0.004), lymphocytes (OR 2.47; p = 0.021), monocytes (OR 2.03; p = 0.021), and LGI (OR 2.90; p = 0.024) were also identified as predictive factors of systemic atherosclerosis in the study population (Table 3).

Predictive factors of systemic atherosclerosis in the study population

| Variables | Systemic atherosclerosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Male | 0.76 | 0.26–2.16 | 0.601 |

| Age | 2.07* | 1.12–3.83 | 0.021 |

| Hypertension | 2.00 | 0.53–7.51 | 0.304 |

| Chronic renal disease | 1.48 | 0.09–24.84 | 0.786 |

| Obesity | 0.97 | 0.15–6.29 | 0.975 |

| Active smoking | 4.39 | 1.01–19.19 | 0.049 |

| Platelets | 2.18* | 1.15–4.13 | 0.017 |

| WBCs | 2.06* | 1.12–3.79 | 0.020 |

| Neutrophils | 2.75* | 1.37–5.49 | 0.004 |

| Lymphocytes | 2.47* | 1.14–5.34 | 0.021 |

| Monocytes | 2.03* | 1.10–3.72 | 0.021 |

| LGI | 2.90* | 1.15–7.29 | 0.024 |

OR expressed per 1 s.d. increase in baseline

The main findings of this study highlight the importance of the LGI as a potential marker for atherosclerotic disease, particularly in individuals under 45 years of age. We also found that elevated values of platelets, WBCs, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes at baseline were associated with systemic atherosclerosis.

In recent studies, Danielsson et al.7 and Mureșan et al.8 highlighted the role of inflammation, exacerbated by hyperglycemia, in advancing vascular disease. In a study by Seoane et al.15, the LGI was shown to predict postoperative complications such as in-hospital mortality, low cardiac output, and acute kidney injury in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting, underlining the importance of this marker in predicting the presence and evolution of the disease.

Villapando-Sanchez et al.16 found that the LGI is correlated with elevated levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and von Willebrand factor, which are considered important mediators of endothelial injury and prothrombotic states. Although our study does not directly investigate endothelial injury, it highlights the importance of inflammatory leukocytes (neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes) in the development of vascular damage. This opens a new avenue for research, supporting the hypothesis that LGI may serve as an early predictor of endothelial dysfunction, potentially before the onset of atherosclerotic symptoms. Consequently, LGI could be used as a screening marker in young individuals at increased risk, such as smokers, obese patients, or those with a sedentary lifestyle.

Another study by de Marañón et al.17 highlights the predictive value of LGI for diabetic patients undergoing endovascular procedures. Similarly to our study, their findings suggest that elevated WBC counts, neutrophils, and LGI are associated with poor long-term outcomes, including an increased risk of major amputation. Moreover, they report a stronger correlation between these markers and severe infrapopliteal atherosclerosis.

Our findings are consistent with these observations, showing that patients with systemic atherosclerosis have significantly higher levels of WBCs and neutrophils, both closely linked to inflammatory processes.

Furthermore, Mureșan et al.8 have shown that an increased LGI serves as an independent predictor of major amputation over the long term, irrespective of conventional risk factors (HR 2.69; p = 0.001). In alignment with these findings, Mureșan et al.6 confirmed the predictive value of LGI for long-term arteriovenous fistula dysfunction, independent of demographic variables, cardiovascular risk factors, and preoperative vascular mapping (HR 3.49; p = 0.037).

The relatively younger demographic within our patient cohort underscores the growing burden of atherosclerosis in populations previously considered at lower risk. Given the high prevalence of smoking in the control group (80%), the need for early lifestyle interventions is evident. Young patients with elevated LGI, especially those who smoke or present additional cardiovascular risk factors, should be carefully monitored for early signs of atherosclerosis, and targeted preventive programs should be implemented for this high-risk population. Additionally, the LGI shows potential as a noninvasive biomarker for PAD in younger individuals and could assist clinicians in identifying those at increased risk of cardiovascular events. However, given its moderate specificity, the LGI should be used in combination with other clinical markers, such as the NLR or traditional cardiovascular risk assessments, to improve diagnostic accuracy.

Despite its promising findings, our study has several limitations, such as the relatively small sample size and retrospective design. Also, the focus on patients from a single center may limit the generalizability of the results. Future research should aim to validate these findings in larger, more diverse populations and explore whether interventions aimed at reducing inflammation and improving glycemic control can reduce the risk associated with elevated LGI. Furthermore, although the LGI shows potential as a predictive marker, it is essential to investigate its role in the long-term prognosis of patients with PAD. Longitudinal studies would be particularly valuable to assess whether lowering LGI through optimized management of glycemia and inflammation can improve clinical outcomes in younger individuals at risk of developing atherosclerosis.

In conclusion, LGI is a promising marker for predicting PAD, as evidenced by its moderate AUC of 0.713 and relatively high sensitivity. These findings suggest a meaningful association between elevated LGI values and an increased likelihood of PAD, highlighting its potential utility as a noninvasive biomarker for identifying patients at risk. Further research is needed to explore the clinical implications of these findings and develop targeted interventions for the prevention and management of PAD in young individuals.