The development of agriculture in particular eras and regions of the world progresses at different paces and under many variable scenarios. They show certain similarities and several differences. Often, their course is a consequence of a combination of important political and economic decisions. These undoubtedly decisions include the decision to join a given country to an existing regional grouping. This is the today’s situation in Ukraine.

Relationships between Ukraine and the European Union (EU) were started in December 1991 when the EU officially recognized Ukraine’s independence. The legal basis for Ukraine’s relationships with the EU is the Law of 01 July 2010 “On the Foundations of Internal and Foreign Policy” [Law of Ukraine No. 2411-VI, 2010]. This law states that one of the main principles of international policy is the integration of Ukraine with the European political, economic, and legal space.

Ukraine received the status of a candidate country for the EU on 23 June 2022. This status determines certain legislative changes and “sets” the direction of the state’s actions, but it does not guarantee that Ukraine will automatically become a full member of the EU. For this to happen, Ukraine must go through a long and difficult way with significant changes in the regulatory and legal area, which will affect every sphere without exception, especially the agrarian one.

The basis of the modern agricultural system of EU countries is the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). The implementation of the solutions making up the CAP allows EU countries to take into account the specificity of the development of their own economy and agriculture. A comparative analysis of the agricultural system of EU countries, but also those outside the EU, in the historical and political context, allows the identification of the main potential and real challenges and risks in the process of shaping the future model of the agricultural system of Ukraine in the context of European integration. In the process of accession to the EU, Ukraine must accept the established EU social order regarding the use of agricultural land and the organization of agricultural activities. Determining the boundary conditions and possible implementation paths in this area of the economy will be one of the most important and complex tasks facing Ukraine. The tasks are shaping the agricultural system taking into account the specificity of the agricultural sector in this country and respecting the provisions of the EU CAP.

The agrarian system currently existing in individual countries is largely the result of globalization processes. Despite this, there are huge disproportions in agriculture in South America, Africa, Asia, and Europe. The world’s poorest countries are net importers of food, even though a large part of their labor force is employed in agriculture and a significant part of the best arable land is devoted to agricultural export production [Weis, 2021]. These countries export sugar, cotton, coffee, tea, palm oil, cocoa, bananas, and tobacco, but they face shortages of grains and meat, which they import from highly developed countries in North America and Europe.

The key suppliers of food and seeds, chemicals, fertilizers, and pharmaceuticals for animals are large multinational corporations. Since pressure from transnational corporations, less-developed countries (LDCs) practically do not consume products from their lands and products attractive for export often replace basic food products, small farmers are unable to compete with powerful business. McMichael [2007] called this the “second dimension” of globalization in the agrarian world, which has led to a fundamental transformation of production and social relationships, “In the context of the above shifts in relations of agricultural production, food security is converted from a local to a global process of social reproduction.” This has led to a large concentration of agricultural land in LDCs, where export-oriented monocultures are cultivated. This is how an agricultural system specific to this group of countries was developed, with the dominance of small, traditional, and most inefficient peasant farms at one extreme and a relatively small group of large farms of the latifundia nature.

In turn, the colonization of the territory of North America deprived the aborigines of most of the arable lands. As a result, commercial agricultural sector was created, which consisted of farmer-settlers, mainly from the countries of “old” Europe. State land distribution in the mid-19th century facilitated the integration of commercial agricultural production with global networks of transnational capital. This was an impetus for the concentration of agricultural land in North America, and at the same time, it was the part of a long history of environmental dispossession among rural farming communities [Wittman et al., 2017]. As a result, a model of intensive agriculture based on a high concentration of land in global corporations was created in the territory of North American countries.

At that time, agriculture in Western European countries did not undergo any significant changes in terms of the land concentration. It mainly developed under the influence of market processes. The countries of this region underwent the process of industrialization much earlier and deeper than other regions of Europe, associated with the outflow of agricultural population to other activities (mainly to industry), which generally had a positive impact on both the agricultural structure and agricultural productivity “driven” by the inflow of capital [Sadowski et al., 2015].

However, the agricultural structure of Central and Eastern European countries was formed under the influence of postwar collectivization processes, which led to the creation of large, mainly state-owned farms, outside Poland and the former Yugoslavia [Eurostat, 2022a].

Nowadays, mainly the CAP and its national specificity determine the structure of agriculture in EU countries, where the selection of appropriate instruments depends on the most important needs in a given country, which are a consequence of the state of the economy and the level of social development [Sadowski and Czubak, 2013].

Adopting high standards of food quality and environmental protection and developing EU agriculture under the auspices of the CAP are not an easy process. Kowalczyk and Sobiecki [2011], emphasizing the main features of the European model of agriculture (EMA), noted that this “agricultural model is determined by a wide range of regulations and restrictions on the one hand and a rich spectrum of benefits on the other.” For decades, the EMA has been operating in a world of regulations, restrictions, barriers, obligations, and also privileges and benefits created by politicians [Kowalczyk and Sobiecki, 2011].

When considering the issues of the evolution of agriculture, at least categories such as “agricultural system” and “agricultural model” should be defined.

According to Stelmachowski [1999], the agricultural system is a system of ownership relationships and forms of organizing production in agriculture, as well as forms of organizing the agricultural market. The agricultural system is an element of the socioeconomic system of the country. Therefore, this is the level of agriculture as a sector of the economy, or the macro level, although the basis of the system is the farm, i.e., the micro scale [Janowska, 2023]. The concept of the agricultural system refers to the country’s economic system, its industrial and commercial, and, above all, agricultural policy. Legal provisions in the field of the agricultural system are intended to lead to the implementation of tasks both at the macro level, for example, in terms of highlighting the importance of agriculture in the development of the state, and at the micro level, primarily compared to shaping the conditions for the rational and effective running of farms [Zasada, 2023].

In the literature on the subject, “agricultural system” is defined as “a method of developing agricultural space in the field of plant and animal production and its processing, taking into account ecological and economic criteria” [Niewiadomski, 1993], as “a well-established social mode of land use agricultural activities and a system of organizing agricultural activities, which at a certain stage of society’s development determines the method of agricultural production as a whole of productive forces and socio-production relations in the countryside” [Kropyvko, 2020], or “a set of interrelated institutions shaping the functioning of agriculture and land use” [Wilkin, 2019].

In turn, a model is one of the most important instruments of scientific knowledge, a conventional image of the object of research (or control, management). The model is constructed by the subject of research (or control, management) in such a way that it expresses the characteristics of the object (properties, mutual relationships, structural and functional parameters, etc.,) important from the point of view of the purpose of the research [Słownik matematyki i cybernetyki ekonomicznej, 1985]. This term can be used to describe not only mathematical models but also economic ones. Since the subject of consideration in this study is the agricultural model, this term should also be defined.

Every company has a business model whether it is articulated and realized or not. In their studies, researchers often adopt their own definitions of a business model. Osterwalder [2004] carried out extensive research on the ontology of the concept of “business model”. He considered a business model as a conceptual tool that allows expressing the business logic of a specific company. At the same time, he believed that the business model is the value that a company offers to customers in order to create profitable and sustainable sources of revenue.

According to Ziętara [2009], the model of Polish agriculture was formed in the process of farm polarization, which led to the development of the following two groups of farms: highly commercial farms and social farms – subsistence or very low commercial farms. Kowalczyk and Sobiecki [2011] wrote about the dual functions of the “European model of agriculture” (food production and development of rural areas). From this, it can be concluded that by the “agricultural model,” they mean that the image of this sector is shaped under the influence of various factors, such as political, economic, ecological, etc.

Taking into account the above factors, we believe that the agricultural business model is an image and an instrument for understanding the process of combining various elements of the agricultural system, such as forms of land ownership, mode of use of agricultural land, methods of developing agricultural space, applied plant, and animal production techniques, and allows to express the logic of this sector on a micro scale, i.e., at the farm level. However, the model of agrarian system is a conceptual tool at the macro level and is created in combination with the agricultural policy implemented by the state, established land ownership relationships, and forms of agricultural market organization.

The basis for distinguishing different agricultural systems is the degree of dependence on industrial means of production, mainly mineral fertilizers and pesticides, and the impact of agricultural production on the natural environment [Zimny, 2007]. According to the above criterion, the following basic agricultural systems can be distinguished as follows: subsistence farming (traditional); industrial (conventional, intensive etc.); organic (ecological, biological-organic, etc.); and sustainable (integrated, conservation, harmonious, ecological, and economic).

The subsistence agricultural system applies primarily to small farms. The advantages of this system are environmental considerations, relatively noninvasive production techniques, and a limited scope of use of agricultural chemicals. However, the disadvantage is low productivity [Burlingame et al., 2019]. According to Eurostat, subsistence farming relates to the agricultural activity to produce food, which is predominantly consumed by the farming household. The food produced is the main or a significant source of food for the farming household, and little or none of the production is surplus and available for sale or trade [Eurostat, 2023a]. A traditional agriculture occurs primarily in Africa and South and Southeast Asia.

The industrial agricultural system refers to large-scale agriculture and uses processes similar to industrial ones, and its goal is to achieve a high productivity because of specialization and intensification of production. Such agriculture dominates in most industrialized countries and increasingly in countries with economies in transition. This is currently the basic agricultural system in the richest countries [Frison, 2016].

The organic agricultural system is a holistic production management system, which promotes and enhances agroecosystem health, including biodiversity, biological cycles, and soil biological activity. It emphasizes the use of management practices in preference to the use of off-farm inputs, taking into account that regional conditions require locally adapted systems. This is accomplished by using, where possible, agronomic, biological, and mechanical methods, as opposed to using synthetic materials, to fulfill any specific function within the system [FAO, 1999].

The sustainable agricultural system meets the needs of present and future generations, while ensuring profitability, environmental health, and social and economic equity. Sustainable Food and Agriculture (SFA) contributes to all four pillars of food security – availability, access, utilization, and stability – and the dimensions of sustainability (environmental, social, and economic) [FAO, 2024].

Morris and Winter [1999], examining the possibilities of developing sustainable agriculture, called it the “third way” of agriculture, namely, an intermediate course in agriculture between conventional and ecological agriculture. This farming system is about maintaining agricultural production, maintaining farm incomes, protecting the environment, and responding to consumer concerns about food quality issues. Slowing or reversing some of the environmental and economic problems associated with specialized industrial agriculture will be aided by the integration of agricultural systems at the producer or community scale [Hendrickson et al., 2008].

Agricultural farms in developed countries, where the industrial farming system currently dominates, are gradually evolving toward a sustainable system. Krasowicz [2009] believed that this system is not a simple return to the organic farming system but a separate agricultural system.

As defined above, apart from agricultural systems, there are agricultural business models. In the area of agriculture, the following business models are most often distinguished: urban agriculture, inclusive agriculture, vertical farming, producer-driven models (cooperative), buyer-driven models (smallholder organization), etc. [Medici et al., 2021]. The decision to adopt one or another model is made by the owner or manager of the farm (enterprise), taking into account its potential and vision.

The aim of this study was to attempt to formulate a strategy for the development and transformation of Ukraine’s agricultural system in the process of accession to the EU. It was assumed that the analysis of historical and organizational-economic conditions would indicate the agricultural systems most useful for Ukraine and the factors determining its choice. The most common contemporary political systems and business models of agriculture in the world will be analyzed. On this basis, the current model of the agricultural system of Ukraine will be compared with the most common models in European and American countries. Sustainable agriculture was treated as a key system of agricultural systems in EU countries. The assessment took into account the possibilities of achieving production and ecological and economic goals, resulting from the analyzed agricultural models.

The research process uses dialectical methods of learning processes and phenomena, the monographic method (analysis of elements of the agrarian policy of EU countries in the management of the development of the agricultural sector), the empirical method (concerning a comprehensive assessment of the current state of the research object), comparative analysis (identification of the problem and direction shaping and development of the agricultural system of Ukraine), SWOT analysis (for analyzing the external and internal environments of the agricultural system and creating a strategy for its development), and abstract and logical (theoretical generalizations and formulating conclusions). Quantitative research was based on the sources of official statistics of Ukraine (State Statistical Service of Ukraine [SSSU], Ministry of Agricultural and Food Policy of Ukraine [MAFPU], and international organizations [FAO]).

The model of agricultural development in the EU countries is a consequence of a combination of historical events in the field of economy and society that took place in these areas. In agriculture, in the vast majority of EU countries, medium-sized individual farms dominate. There are currently 9.1 million of them, including approximately 2/3 with an area of <5 ha and as many as 95.0% have the status of family farms. At the opposite end of the EU agrarian structure, there are large farms, i.e., those with >50.0 ha of agricultural land. There are only 7.5% of them, but they occupy almost 70.0% of agricultural land [Eurostat, 2023b].

In some EU countries, large farms dominate, as a consequence of the previous agricultural system based on state ownership in agriculture. The opposite of this model is Polish agriculture, where there are 1.3 million farms, most of them with an area of 1–20 ha. According to the data from the Statistics Poland for 2020, they accounted for 86.9% of the total number of farms, and they used 43.4% of agricultural land (6.5 million ha). The number of farms with an area over 50 ha is 3.1%, but they use 35.2% of agricultural land (5.3 million ha) [Główny Urząd Statystyczny, 2022].

The land ownership structure in the Western EU countries is an intermediate model compared to the two models mentioned above. Family farms with individual ownership constitute 85.0% of the total number of agricultural enterprises, cultivate 68.0% of agricultural land, and produce 71.0% of agricultural products (EU-15) [Eurostat, 2022b]. Of course, there are also significant differences between countries in this group. For example, agriculture in Italy and Austria is based on small- and medium-sized family farms. In Spain, Germany, and France (to a lesser extent), larger farms belonging to both corporations and individual farmers dominate. However, even large farms in this group are much smaller than agricultural enterprises in selected countries of Central and Eastern Europe (Czech Republic, Slovakia). Regardless of the common opinion about the efficiency advantage of large-scale agriculture, EU countries support family farms and try to keep the processes of area concentration at a relatively low level [Eurostat, 2022a].

In EU countries, there are no strict restrictions on the purchase/sale of agricultural land (including for foreigners). Existing regulations mainly concern land use issues. However, EU law aims to prevent the creation of large corporate landholdings and preserve the family nature of ownership in this sector. A partially different policy prevails in some CEE countries, where governments often support the interests of large agricultural producers at the expense of individual farms.

The agricultural policy of most EU countries, despite the often-expressed position on the advantage of large farms over small farms, usually gives priority to preserving the family structure of agricultural ownership. This approach has economical, social, and environmental justification. Individual owners focus on ensuring parity profitability of their farms, while agricultural corporations (agroholdings) focus on maximizing profit (ROI). Family farms provide a workplace for the owner farmer and his family, corporations minimize labor inputs through capital-intensive intensification, family farms to varying degrees are interested in the state of the natural environment, treating it as a place of work and life, and corporations usually use monoculture, based on the high and very high use of agricultural chemicals (plant protection products and mineral fertilizers), which leads to rapid degradation of the natural environment, also typically agricultural (contamination and sterility of soil, erosion, pollution of watercourses, and loss of organic substances in the soil).

Family farms are usually interested in purchasing even small agricultural plots (up to 1 ha) because with a farm size of 5 ha or 10 ha, even such a small increase in the area results in a significant increase in production and income. The size of these farms ensures high competition between them, which leads to an overall increase in land values. Unlike this group, agricultural corporations are interested primarily in purchasing large plots of land located in compact complexes, often with an area of several hundred hectares.

Despite modern technologies, large investment outlays, and generally abundant resources ensuring large-scale production and sales, large agricultural farms (enterprises) often inferior to family farms in terms of the yield of crops such as vegetables, fruits, and soft fruits. Despite high capital expenditure, they have similar yields of wheat, sunflower, and rapeseed.

The source of success of family farms is often the diversification of production (crops and animal husbandry), entering subsequent stages of the food chain (processing and food trade) and adopting new methods of organizing agricultural production, such as ecological, sustainable, or low-invasive farming (ploughless and plowless farming). As a result, products with higher added value are produced, although on a smaller scale. In addition, family farms often specialize in growing more profitable crops such as vegetables, fruits, herbs, and animal breeding, which are activities that corporations tend to ignore. Such a dual image of modern agriculture is visible both in the EU countries and in other regions, including Ukraine.

An agricultural system based on family farms requires much greater expenditure from the state than a system based on large agricultural corporations. However, the advantages of family farming in terms of environmental protection, the rural labor market, and the preservation of biodiversity increasingly support the need to choose this path of development, or at least recognize its advantages and support it.

The process of transformation in Ukraine’s agriculture began when the country regained independence in 1991. In total, in the years 1991–2000, 27.2 million hectares of agricultural land were transferred free of charge to the ownership of agricultural enterprises established on the basis of former collective farms [Resolution of the Supreme Council of the USSR No. 563-XII, 1990].1 The next stage of the reform (1996) was to provide eligible persons with certificates confirming their right to share in the land. In this way, starting from 01 January 2001, 6.48 million former collective farm workers acquired land ownership rights. In total, the right to 26.5 million hectares of agricultural land was granted [Decree of the President of Ukraine No. 720/95, 1995]. This process was aimed at establishing individual peasant farms in Ukraine [Law of Ukraine No. 742-IV, 2003]. As a result of the reform, the state lost its monopoly position in land ownership. By the end of 2000, almost 70.5% of agricultural land passed into private ownership, and 21.0 million Ukrainian citizens became the subjects of ownership relationships. Due to the reform, almost 15,000 farms were created based on former collective farms meaning new economic entities (agricultural enterprises). The process of transforming collective farms into agricultural enterprises and farms also led to the emergence of a new phenomenon in Ukrainian conditions: land leasing [Law of Ukraine No. 161-XIV, 1998]. In the initial period, the area of leased agricultural land was 22.4 million hectares (2001). Former collective farm workers with agricultural enterprises from which they purchased land, 5% with individual farmers, and the remaining 15% with other entities [Ukrainian Center for Economic and Political Research, 2001] concluded over 80% of lease agreements.

The consequence of the leasing process was the preservation of the integrity of agricultural land (cultivation complexes), with a radical change in ownership relationships. It was also an impulse for even greater concentration of agricultural land and the creation of agroholdings. The original idea of the agrarian reform was to empower and transform hired workers of former collective farms into individual farmers. However, the lack of financial resources in the form of means of production, too small areas of land granted (up to 2 ha), and the location of relatively small plots within large connected agricultural areas prevented the mass establishment of independent, individual farms. This, however, led to a high concentration of land and its control by large-scale agricultural enterprises [Zolotnytska and Kowalczyk, 2022].

Taking into account the above, it should be emphasized that Ukraine has an exceptionally complex agricultural structure, which is a consequence of the socialist past within the USSR and subsequent privatization processes and agricultural reforms implemented by an independent state. The agricultural sector of Ukraine is represented by legal entities (agricultural enterprises, farms, economic associations, and production cooperatives) and natural persons (private peasant households [PPH]) [Law of Ukraine No. 742-IV, 2003; Law of Ukraine No. 973, 2003] (Table 1).

| Size (ha) | Private peasant households | Farms | Agricultural enterprises | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thousands of pcs. | Thousands hectares | pcs. | Thousands hectares | pcs. | Thousands hectares | |

| Up to 1 | 3,066.6 | 4,785.8 | – | – | – | – |

| 1–5 | 717.6 | 1,120.0 | 1,766.0 | 5.8 | – | – |

| 5–10 | 82.4 | 128.5 | 1,790.0 | 5.4 | 37.0 | 8.9 |

| 10–50 | 54.9 | 85.7 | 11,632.0 | 266.7 | 711.0 | 24.9 |

| 50–100 | – | – | 4,641.0 | 323.0 | 679.0 | 159.5 |

| 100–500 | – | – | 6,771.0 | 1,620.5 | 2,600.0 | 669.8 |

| 500–1,000 | – | – | 1,262.0 | 897.7 | 1,966.0 | 1,416.4 |

| 1,000–5,000 | – | – | 926.0 | 1,581.6 | 3,919.0 | 8,568.8 |

| Over 5,000 | – | – | – | – | 601.0 | 5,273.8 |

| Total | 3,921.5 | 6,120.0 | 28,788.0 | 4,700.7 | 10,513.0 | 16,122.1 |

Source: Own study based on State Statistical Service of Ukraine [2022].

According to the SSSU data, on 01 January 2022, there were 3.9 million individual owners in Ukraine, registered as private peasant households. These farms cultivate 6.1 million hectares of agricultural land, which constitutes 14.8% of the total agricultural area in Ukraine. There are 10,513 agricultural enterprises operating on an area of 16.1 million hectares and 28,788 farms on an area of 4.7 million hectares. About 2.4 million hectares are set aside. The total area of agricultural land in Ukraine is 41.3 million hectares. The remaining area, i.e., approximately 12.0 million hectares, is legally assigned to 21.0 million Ukrainian citizens. Distinguishing them among PPHs is very complicated because such households and typical PPH conduct agricultural production for their own needs and can sell it on local markets. For the purposes of further analysis, only PPH was included in this study because they are a potential agricultural farm.

The average area of private peasant households is 1.56 ha. The largest farms cover an area of up to 50 ha of agricultural land. In turn, farms are more diversified in terms of area: from the smallest with an area ranging from 1 ha to 5 ha and to the largest with an area of up to 5,000 ha, with an average area of 163.3 ha. The largest agricultural enterprises in terms of area are approximately 10.5 thousand (2021) and have an average area of 1,533.5 ha. These entities belong to the group of large enterprises and represent not only agricultural enterprises but also agroholdings.

Agroholdings were created as a result of privatization processes of agricultural land, with the assumption that they would be a highly effective form of agricultural production management, responding to market requirements [Law of Ukraine No. 3528-IV, 2006]. Agroholdings were to restore the severed intersectoral connections between agricultural and processing enterprises.

The problem is that agroholdings and subordinate companies do not declare that they conduct business as Ukrainian farms. As a rule, they are registered abroad, which provides them with preferential tax conditions, and in Ukraine, they pay only relatively low agricultural tax. Therefore, it is practically impossible for Ukrainian administrative authorities, including fiscal ones, to officially control and analyze the establishment and dynamics of functioning of these companies as agricultural market operators because their activities are not fully reflected in either official statistics or submitted financial reports.

The creation and liquidation of these companies are extremely dynamic. A process of rapid concentration can be observed in this sector, where existing agribusiness structures are absorbed by others, creating agricultural mega-farms (with an area of up to 0.5 million hectares of agricultural land) [Marunyak et al., 2021] with high availability of assets and significantly diversified loan portfolio.

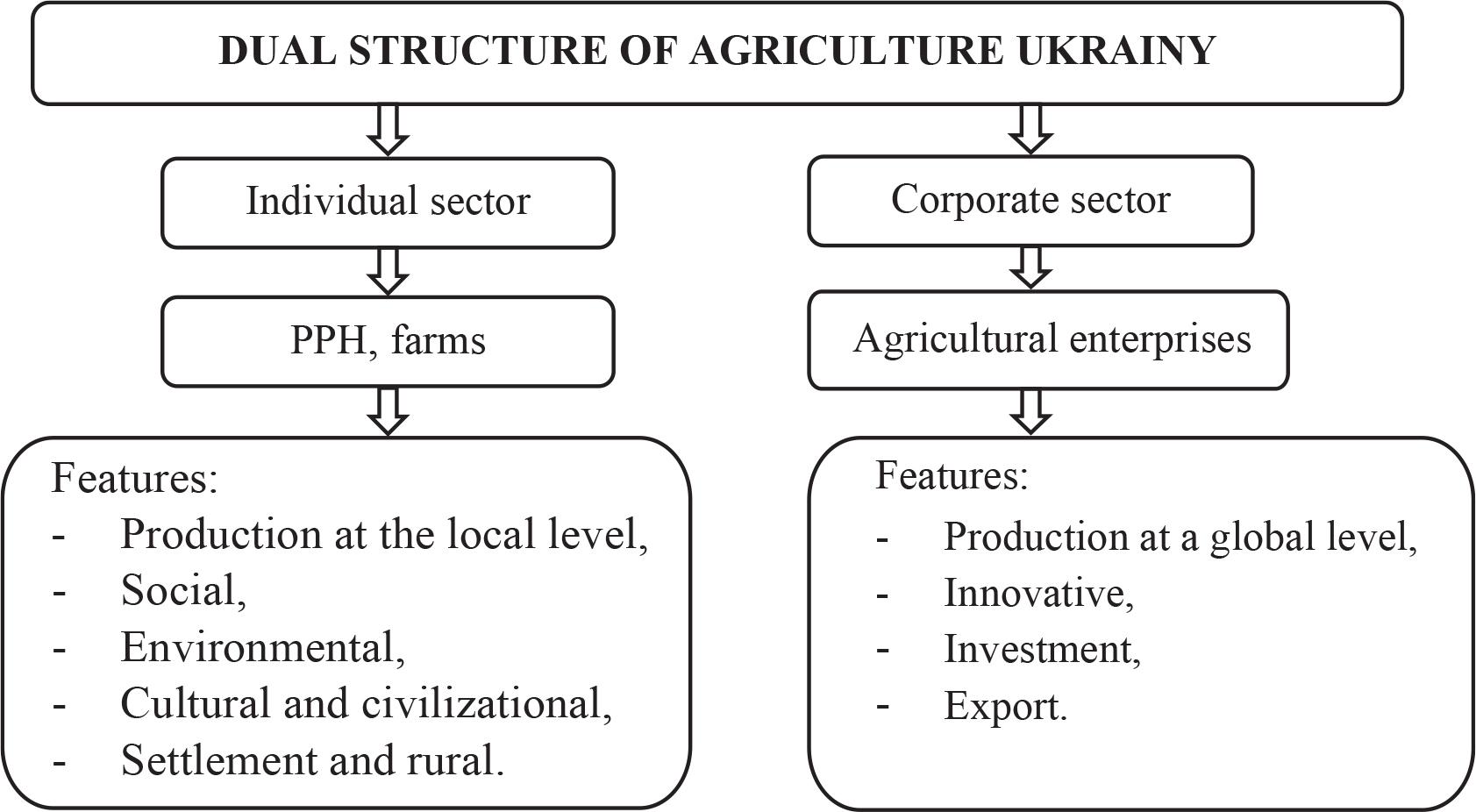

Each of the above-mentioned types of farms and agricultural enterprises is a component of the agricultural structure of Ukraine (Figure 1).

Model of the agricultural system of Ukraine.

Source: Own study based on Marunyak et al. [2021].

The individual sector fulfills key elements of the national agricultural and rural development policy, such as environmental protection, improving the quality of life in the countryside, actions to reduce the environmental burden, introducing environmentally friendly technologies, and caring for animal welfare. Important functions of farms and private peasant households include meeting food needs and providing income to the rural population.

The economic activity of agricultural enterprises is focused primarily on generating profit and rent, which is a form of surplus resulting from the use of limited, diversified resources (including land). Taking into account the fact that agroholdings have access to foreign markets, they obtain a high income from rent due to low labor costs in Ukraine. The main sources of rent are differences in local production conditions and state regulations.

As a result of the ongoing structural and market changes, the agricultural system of Ukraine has been shaped, which includes all its key elements, such as subsistence agricultural – PPH, industrial agricultural – agricultural enterprises, and organic and sustainable – agricultural farms. The activities of large agricultural enterprises (including agroholdings) are oriented to the needs of the global market (export), farms – to the traditional local consumer market, and the activities of private peasant households – to meet their own needs and sell surpluses on local markets.

The current agricultural system of Ukraine is the result of adapting agriculture to the real operating conditions of the economy during its market transformation. The basic social and market forces influencing the current shape of the agricultural system of Ukraine are, on the one hand, the expectations of residents related to this sector and the need to ensure food self-sufficiency of citizens and, on the other hand, lobbying of centers associated with large agricultural property and capital engaged in agriculture, primarily in form of agroholdings.

To formulate possible scenarios for the transformation of Ukraine’s agricultural system in the process of accession to the EU, the main organizational, economic, political, and natural and climatic factors were identified (Table 2).

| Parameters | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|

| Agricultural potential | S1 – large area of agricultural land; | W1 – high concentration of agricultural land used by agroholdings; |

| S2 – high soil fertility; | W2 – deterioration of soil quality due to intensification of agricultural production (monoculture); | |

| S3 – sufficient manpower; | W3 – lack of sufficient means of production on small farms; | |

| S4 – favorable natural and climatic conditions; | W4 – increasing climate risk in agriculture as a result of global climate change; | |

| Compliance of quality parameters and technology with EU regulations | S5 – implementation of approximately 70% of EU regulations in the agricultural sector of Ukraine *; | W5 – lack of sufficient knowledge of farmers in the field of farming in accordance with EU regulations; |

| W6 – focus of agroholdings on maximizing profits; | ||

| W7 – high cost and reduced efficiency by implementing GAEC standards; | ||

| Access to sales markets | S6 – high demand on the internal market and established sales channels on external markets. | W8 – loss of some export channels (Black Sea ports) and the associated increase in logistics costs and loss of part of the southeastern sales markets. |

| Parameters | Opportunities | Threats |

| Demand | O1 – access to EU sales markets as an EU member; | T1 – possible restrictions (transition periods) and production quotas; |

| Competitiveness | O2 – low cost of plant production and its high efficiency; | T2 – possible expansion of food of animal origin from other EU countries to the Ukrainian market; |

| EU agricultural policy | O3 – high level of support for small- and medium-sized agricultural producers in accordance with EU regulations; | T3 – a powerful lobby of agroholdings in the parliament and government of Ukraine; |

| O4 – possibility of implementing investments and innovations in the agricultural sector; | T4 – high cost of implementing environmental norms and standards in the agricultural sector; | |

| O5 – improving soil quality and, as a result, repairing environmental damage; | T5 – collapse of some agricultural producers who fail to implement EU regulations; | |

| O6 – increasing the number of organic producers. | T6 – increase in prices for groceries. |

Source: Own study.

According to data Ministry of Agrarian Policy and Food of Ukraine.

The next step of the strategic analysis regarding the prospects for the development of the agricultural system of Ukraine during accession to the EU is the construction of a SWOT analysis matrix with SO, ST, WO, and WT strategies (Table 3).

| Strengths | SO strategies | ST strategies |

|---|---|---|

| O2 – low cost of plant production and its high efficiency; | T1 – possible restrictions (transition periods) and production quotas; |

| S5 – implementation of approximately 70% of EU regulations in the agricultural sector of Ukraine; |

|

|

| S6 – high demand on the internal market and established sales channels on external markets; |

|

|

| Weaknesses | WO-strategies | WT-strategies |

|

|

|

| W8 – loss of some export channels (Black Sea ports) and the associated increase in logistics costs and loss of part of the south-eastern sales markets. | O1 – access to EU sales markets as an EU member. | T1 – possible restrictions (transition periods) and production quotas. |

Source: Own study.

The conducted SWOT analysis allows forecasting possible scenarios for the development of Ukraine’s agricultural sector during accession to the EU. There are three such variants: optimistic, pessimistic, and neutral.

The optimistic scenario is based on the assumption of implementation of the full provisions of the CAP and the principles of sustainable agricultural development by all forms of farming. Such a scenario will support the adjustment of land prices in Ukraine to the level of Central and Eastern European countries (Czech Republic, Bulgaria, Poland, Romania, and Lithuania). This will result in an increase in the costs of agricultural production of agricultural enterprises and a reduction in productivity per 1 ha of agricultural land (in accordance with GAEC standards). This may result in a lower level of land concentration within agroholdings. Expropriated arable land may become the basis for the development of organic and sustainable agriculture by PPH. The optimistic scenario includes the prospect of partial demonopolization of agricultural production, increasing the competitiveness of farms, developing agritourism and socioeconomic development of rural areas, preserving and restoring the traditional cultural landscape, and reducing anthropogenic pressure on the environment.

The pessimistic scenario is diametrically opposite and definitely undesirable in its scope and consequences, in which it is assumed that Ukraine will not be admitted to the EU, which will result in an increased increase in the influence of agricultural enterprises, including agroholdings. However, the lack of EU funds for the modernization of Ukrainian agriculture and food processing will be of fundamental importance. There will also be conditions conducive to lowering the quality of agricultural raw materials, uncontrolled consumption of agricultural chemicals, and progressive processes of environmental destruction. In this variant, the risk of economic collapse of rural areas will increase. This is primarily about the increase in the level of unemployment in rural areas, migration, decline in farmers’ income, and, as a result, degradation of the socioeconomic and natural landscape of the Ukrainian countryside. Overall, this may mean a gradual evolution toward an agricultural model typical of South American countries. This will mean systematically progressing stratification of agriculture and rural areas.

In addition to the optimistic scenario, a neutral scenario also seems likely, which assumes Ukraine’s accession to the EU and the preservation of existing territories and influence of farms (agroholdings) with limited redistribution of land to farms but without a significant change in the subjective structure of the market. Ukraine’s admission to the EU will mean implementing all EU regulations and strengthening the role of farms. To mention is that the opening of the land market to foreign capital will result in some municipalities and even regions remaining subject to intensive agriculture conducted by large agricultural enterprises.

The decisive impact on the strategy, pace, and depth of reforms implemented in EU countries, especially in their initial period, had the initial conditions, which depended, among others, on the degree of centralization of the agricultural management system, the needs for the restitution of ownership relationships in this sector, the scope of cooperation between various branches, economy, and finally also on national traditions and the nature of social relationships. In these circumstances, each country shaped its own variant of land privatization, restructuring, and organization of agriculture, differently approaching its own model of the agricultural system.

Recognizing the fact that agriculture is an integral element of the national economy and within the EU, all countries base its development on the provisions of the CAP means that the main pillars of the adopted strategies are as follows: food security, quality of life, and development of rural areas. They place an emphasis on maintaining the land in good condition and support research, advisory, and educational and investment activities in the field of agricultural activity. The adopted structure supports the concept of sustainable development, helping to blur socioeconomic differences.

The conducted research, including SWOT analysis, allowed for the identification of key elements of the development strategy and transformation of Ukraine’s agricultural system in the process of accession to the EU, which are as follows: legally established forms of land ownership, the degree of adaptation of agricultural legislation to EU requirements, the development of human capital, social conditions, and economic, and finally, forms of organizing the agricultural market.

The analysis allowed to develop the following three possible scenarios for the development of Ukraine’s agricultural sector in the EU accession process, i.e., optimistic, pessimistic, and neutral.

The implementation of the optimistic scenario, based on the EU legal acquis in the area of agriculture and rural areas, is only possible through a deep evolution of the currently dual structure of Ukraine’s agricultural system. This will result in transformations in the structure of the agricultural system in favor of the private sector in the form of individual farms. This will require the reorganization of economic units, reducing the level of land concentration, adapting and meeting all conditions arising from European law, and including food safety, environmental protection, and animal welfare.

An alternative to such a scenario is for Ukraine to remain outside the EU structures, which in the case of agriculture will mean deepening its dual character, gradual liquidation of individual farms, and further stratification of the agricultural system.

Shaping the agricultural system is an exceptionally complex task that requires time and consistency in implementing the necessary changes. This complexity is clearly illustrated by the matrix of relationships between the strengths and weaknesses of the current agricultural system of Ukraine and its opportunities and threats in the accession process. The history of shaping agricultural systems in the world proves that there is neither one universally acceptable model of this system nor one path leading to it. In this process, each country must both benefit from the experience of others and take into account its own specificity and development opportunities.