The economy of most African countries is primarily based on income generated by the agriculture and agroforestry sectors through the marketing of food crops and non-timber forest products (NTFPs) (Reta et al., 2020). NTFPs have always been an essential source of income for African countries and provide a livelihood for local communities (Animashaun & Toye, 2013). Conversely, many case studies have reported a decline in the productivity of several non-timber forest product species of African ecosystems and agrosystems. This loss is mainly linked to insufficient investment in developing silvicultural itineraries and restoration or conservation activities targeting these species (Fandohan et al., 2008). It is also related to the non-use of high-performance plant material (Mbété et al., 2011), the difficulties of producers in accessing reasonable technical assistance, and the effects of climate change (Asogwa et al., 2012b).

Cola nitida (Vent.) Schott & Endl (Malvaceae) is one of the highly valued NTFPs in Africa for its multiple uses (Savi et al., 2019). The species is essential in providing ecosystem services such as food supply and raw materials for agro-food industries and pharmaceutical companies (Asogwa et al., 2006). Cola nitida wood is also an excellent fuel for rural communities (Lim, 2012). Moreover, C. nitida facilitates the restoration of degraded ecosystems and plays a cultural role in African countries (Agwu et al., 2022). However, despite the importance of this species, a decline in its population is observed in the forests and agrosystems of Africa (Asogwa et al., 2006). Indeed, C. nitida is threatened by logging, slash-and-burn agriculture, firewood collection, and land clearing through its native habitats (Savi et al., 2019). Climate change is also expected to increase these threats by imposing additional physiological constraints on C. nitida (Agwu, 2020). According to Agwu (2020), climate change induced the loss of 27% of suitable areas for conservation and cultivation in Nigeria. In response to these constraints, species propagation is one of the approaches adopted by local communities to ensure the sustainability of the goods and services provided by the species (Savi et al., 2019). However, the species’ propagation is often limited by insufficient soil water availability (Agwu et al., 2022), the lack of adequate technical itineraries for its production, the unavailability of improved C. nitida seeds for cultivation (Deigna-Mockey et al., 2016), and declining soil fertility (Ndubuaku & Asogwa, 2003). These constraints can hinder the optimal growth of C. nitida seedlings, compromise the productivity and profitability of orchards, and consequently impact the willingness of local communities to be more involved in the species’ production (Ndubuaku & Asogwa, 2003).

Before identifying or proposing new innovative methods to increase the species’ population, it is essential to provide an updated overview of the research conducted on the species. A systematic review is important for policymakers to decide on a conservation strategy (Pullin & Stewart, 2006). It also serves as a basis for researchers and growers to understand the benefits of a species’ production, examine recent production strategies, and identify under-explored research areas. Compared to traditional narrative reviews, systematic reviews use explicit and reproducible methods to identify, critically evaluate, and combine the results of targeted primary research studies across multiple databases based on relevant eligibility criteria (Pollock & Berge, 2018). An updated systematic review on C. nitida in Africa will help identify and synthesize existing relevant studies on the species and highlight less explored research avenues.

Despite some efforts to develop updated literature reviews on C. nitida, these have been limited to the knowledge of the species’ phytochemical, pharmacological, and toxicological properties (Mbembo et al., 2021). The gap in the state of scientific knowledge on the species is still significant. For example, the point of knowledge on C. nitida seed germination methods has been established since the 1970s (Brown, 1970). However, slow germination and seedling growth are among the difficulties that could impact the local people’s decision to be further engaged in the production of Cola nitida species (Mbété et al., 2011). While some recent research has contributed to improving seed-sowing methods to shorten germination times (Mbété, 2007; Legnate et al., 2010; Gbedie et al., 2017), the results of these studies have not been synthesized to update the review proposed by Brown (1970). Moreover, according to Ahamide et al. (2015), various types of pests hinder the productivity of C. nitida. Several researchers have proposed research work involved in the control of these pests. Producing an updated critical synthesis of these control methods would be crucial in facilitating the selection of effective strategies for producers. Furthermore, it will contribute to identify future research avenues for enhancing pest control processes. To address this knowledge gap, this study mainly aims to review the current knowledge and future research perspectives on the sustainable conservation and cultivation of C. nitida in African countries. Specifically, the study sought to

- (i)

synthesize available knowledge on C. nitida and the threats that hinder its conservation and management in African countries, and

- (ii)

identify future research perspectives that would contribute to the species’ sustainable management in African countries.

The systematic review was conducted using the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) method (Page et al., 2021a; Page et al., 2021b).

The review of existing knowledge and research perspectives on C. nitida was developed from the available literature gathered via various search engines, “Google Scholar” (https://scholar.google.com), and the databases Research4life (https://www.research4life.org); Science Direct (https://www.sciencedirect.com); Scopus (https://www.scopus.com) and African Online Journal (www.ajol.com) using a combination of different keywords such as: “Cola nitida; Colatier; bitter cola and Kola nut”(Lim, 2012).

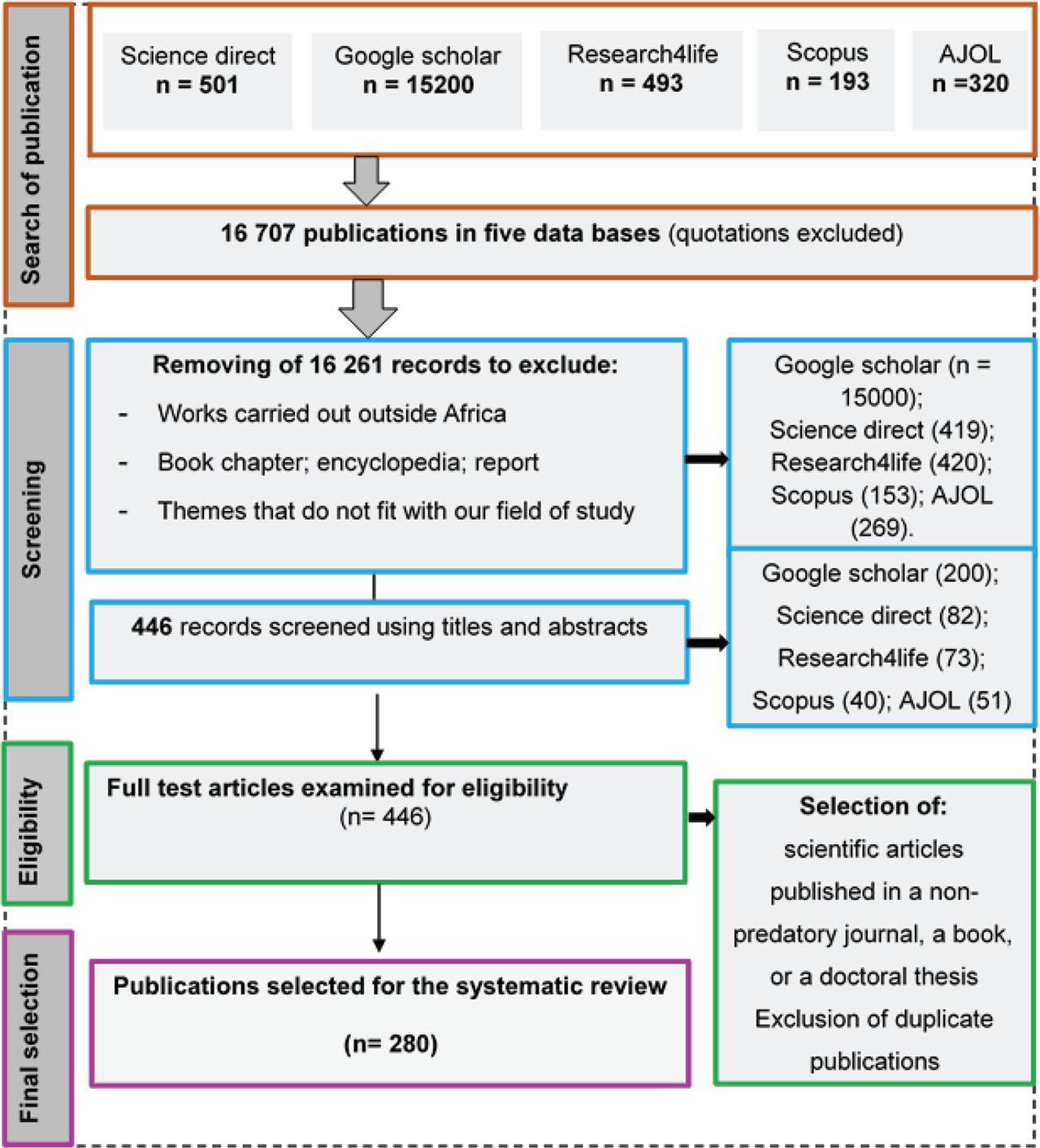

Our approach was fruitful, identifying a significant publication on Cola nitida. We found 15,200 publications (quotations excluded) in Google Scholar (the search was conducted on January 08, 2023); 501 in the database Science Direct (the search was conducted on January 21, 2023); 493 in the database “Research4life” (the search was conducted on February 19, 2023); 320 publications in the African Online Journal (consulted February 14, 2023) and 193 publications in the Scopus database (consulted on February 02, 2023) (Figure 1).

Diagram showing the selection process of publications used.

Then each of the main themes “Cola nitida; Colatier; bitter cola; Kola nut” was combined with a set of keywords such as: “Botany; geographic distribution; physiology; phenology; ecophysiology; genetic diversity; conservation strategies; propagation’ challenges; climate change impact” using the Boolean operator “AND” over the period from 1990 to 2022 in https://scholar.google.com (consulted from January 10 to 14, 2023), https://www.research4life.org (consulted from 20 to 24 February 2023); https://www.sciencedirect.com (consulted from January 22 to 25, 2023); https://www.scopus.com (consulted from 03 to 07 February 2023) and www.ajol.com (consulted from February 15 to 17, 2023). This approach ensured that we obtained relevant documents, focusing specifically on finding studies of the species in Africa, without limiting ourselves to African researchers or publications in exclusively African journals.

Search results were screened for all databases using publication titles, abstracts, and keywords. Duplicate publications were excluded. All recorded publications were reviewed in five steps described as follows:

Step 1: The document type must be a scientific article published in a non-predatory journal, a book, or a doctoral thesis.

Step 2: Checking the relevance of the publication based on the title.

Step 3: Reading abstracts to determine whether they were relevant to the review.

Step 4: Downloading and reading the full article when the second step has not provided sufficient information to justify its inclusion in the review.

Step 5: Retrieving publications that met the inclusion criteria for this review.

The selected publications were read to do a critical analysis and summarize the results’ content. While reading these documents, we further identified other relevant sources through their bibliographic references, which were downloaded and thoroughly reviewed. In addition, direct contact was made with some authors to request access to publications or theses that were not freely available.

The following information was collected for each recorded paper: the title, the author’s name, the location of the study, the year of publication, the name of the journal where the article was published, the study objectives and aspect(s) addressed in the study which might be either of the following aspects: (1) use and socio-economic importance; (2) study on the morphological and genetic diversity of C. nitida; (3) study on improving the species’ propagation techniques; (4) study on the nutritional and chemical properties of the nut; (5) studies on pest and pesticide control; (6) taxonomy, botanical description, distribution and ecology of the species; (7) climate change threat on the species. Spatial distribution maps based on the number of publications by African countries and per the African region were created using the QGIS software version 3.14.

Sixteen thousand seven hundred and seven (16,707) publication records were initially identified across the five scientific databases. Out of these, 16,261 publications (e.g. research done outside Africa, book chapters, encyclopedias, reports, and fields of study that do not fit ours) were excluded during the screening and refining steps. 446 eligible publications (Google Scholar (200); Science Direct (82); Research4life (73); Scopus (40); AJOL (51)) were thus considered for full abstract (and text) screening. After the screening process and duplicate extraction, 280 publications were finally included in the systematic review (Figure 1). These 280 studies were published over three decades (1990–2022) in Africa, as considered for this review.

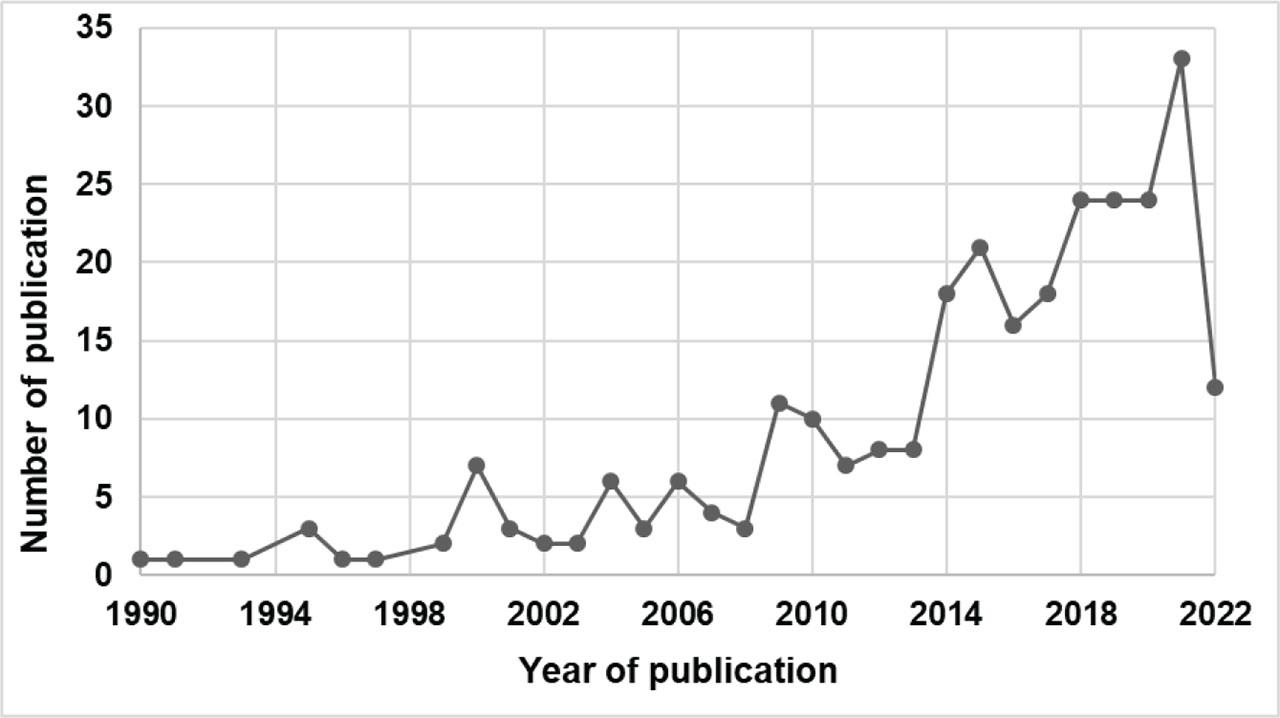

Figure 2 shows the trend of scientific publications on C. nitida from 1990 to 2022. Based on the 280 papers published over the three decades in Africa, 208 were published between 2012 and 2022, and 34 publications in 2021 alone. This result reflects the growing research effort towards C. nitida in Africa. In fact, there were few publications on C. nitida (n = 17) during the first decade (1990–2000). The low number of publications during this period may be due to the lack of knowledge of its socio-economic potential. It could also be linked to the availability of other NTFPs used by local communities for their domestic needs, which was the reason why the species was not yet over-exploited. There was therefore no need to conduct work on the sustainable management of the species. However, the number of publications increased over the second decade (n = 50) and third decade (n = 213). The growing research interest on C. nitida can be attributed to the importance of its nuts for major industries. Indeed, the first studies on the species’ nutritional and phytochemical properties, such as those of Abulude (2004), have shown that C. nitida nuts can be used in the pharmaceutical, food, and textile industries. This work could spark the interest of significant industries and researchers in further investigating the species’ uses.

Scientific publications made on C. nitida in Africa from 1990 to 2022.

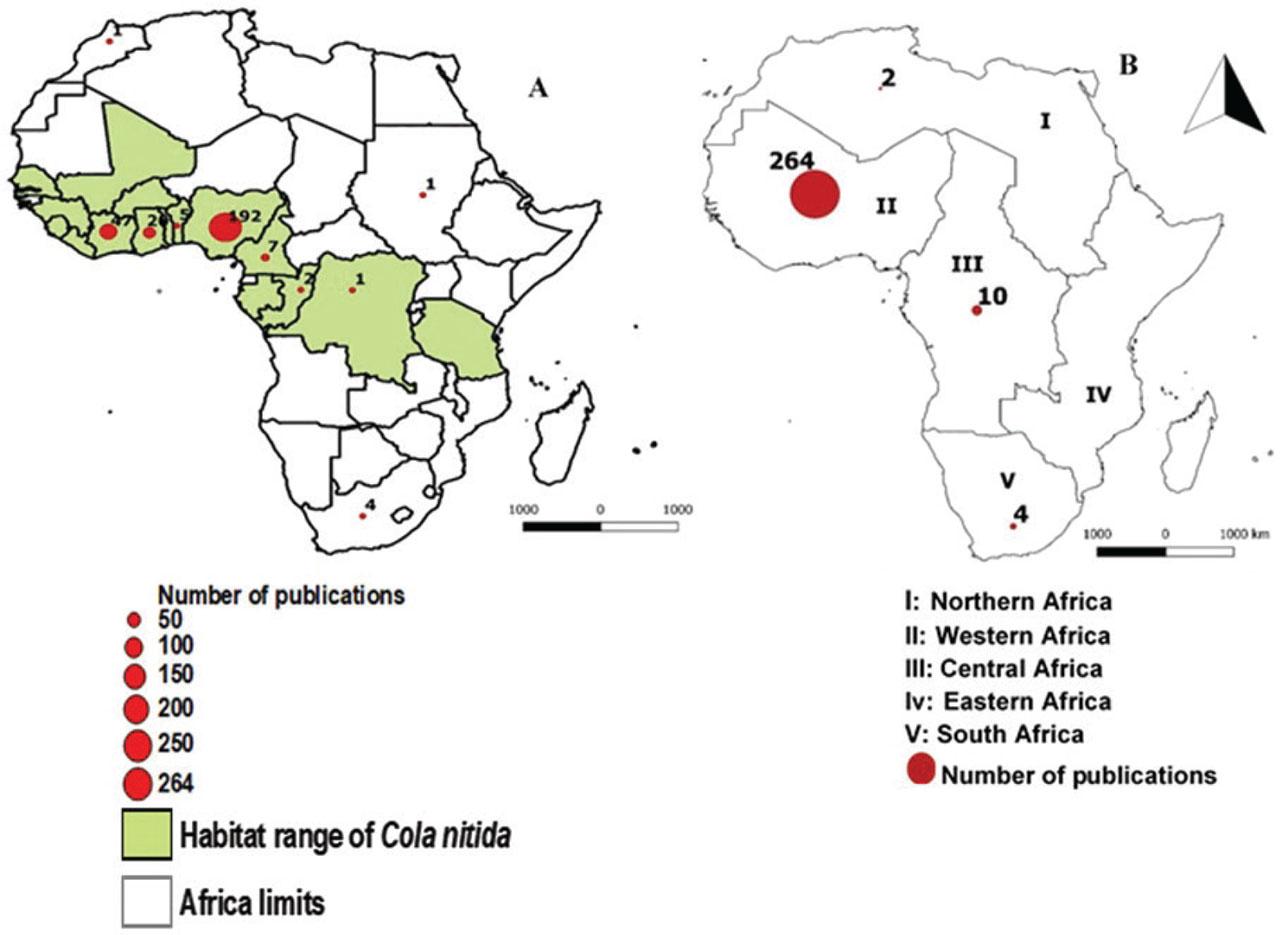

All the 280 research works were from four African sub-regions (North Africa, South Africa, West Africa, and Central Africa). Most of these publications were from West Africa (n = 264), followed by Central Africa (n = 10), and to a lesser extent from other sub-regions such as South Africa (n = 4) and North Africa (n = 2) (Figure 3B). At the country level, our study showed that publications on C. nitida covered 10 African countries including mainly Nigeria (n = 192), Côte d’Ivoire (n = 47), Ghana (n = 20), Cameroon (n = 7), Benin (n = 05), South Africa (n = 4), Congo Brazzaville (n = 02), Morocco (n = 1), the Democratic Republic of Congo (n = 1), and Sudan (n = 1) (Figure 3A). These results illustrate that West Africa has contributed more to research efforts on the sustainable management of C. nitida than other regions. This trend could be explained by the species’ high socio-economic and cultural use value in West Africa (Asogwa et al., 2012a; Dah-Nouvlessounon et al., 2016). Furthermore, given that C. nitida occurs in tropical and subtropical zones (Opeke, 1992), countries whose climatic conditions do not converge with the ecology of the species might not be too interested in research work related to the sustainable management of the species.

Geographical trend of publication on C. nitida (1990–2022) by country (A) and by sub-region (B).

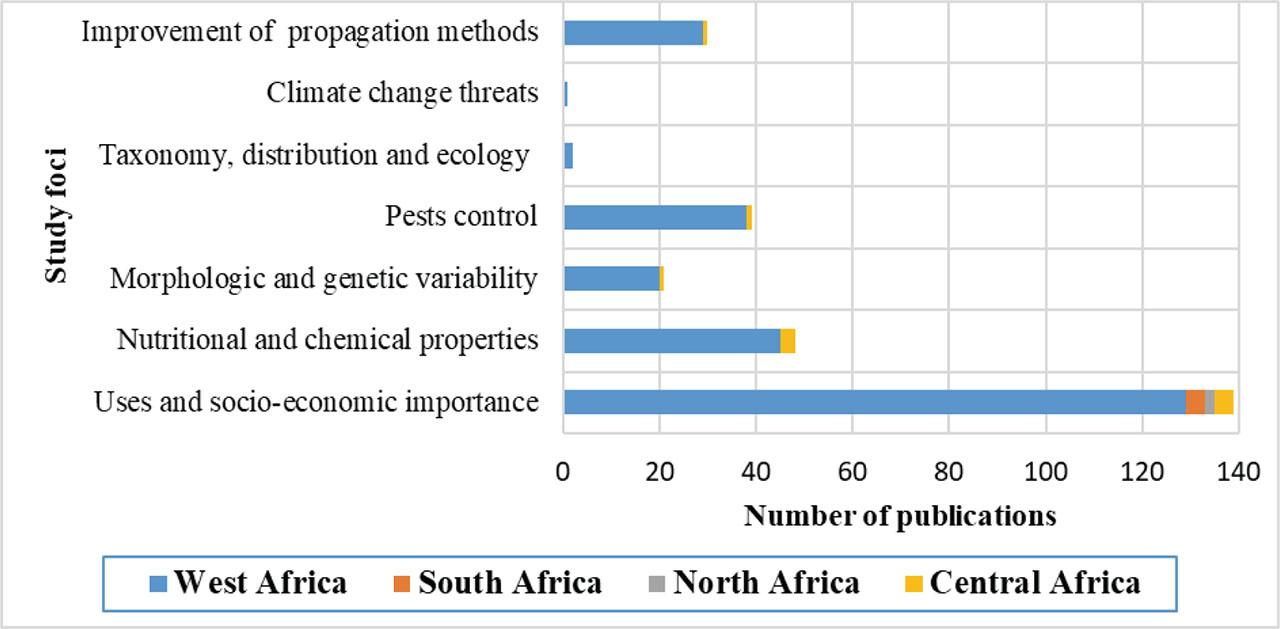

The scientific publications on C. nitida, according to the seven (07) predefined themes from 1990 to 2022, have been mainly carried out in West Africa (Figure 4). Approximately half (n = 140) of research on C. nitida has been carried out on the species’ uses and socio-economic importance. 17% of research works (n = 48) have been carried out on the nutritional value and phytochemical properties of its organs; 15% (n = 39) on the pest control and nut conservation strategies; and 11% (n = 30) on the improvement of propagation methods. The research works on morphological and genetic diversity (n = 21) and those on taxonomy, botanical description of the species, geographic distribution, and ecology (n = 2) received less attention.

Number of publications per study focus on African regions (1990–2022).

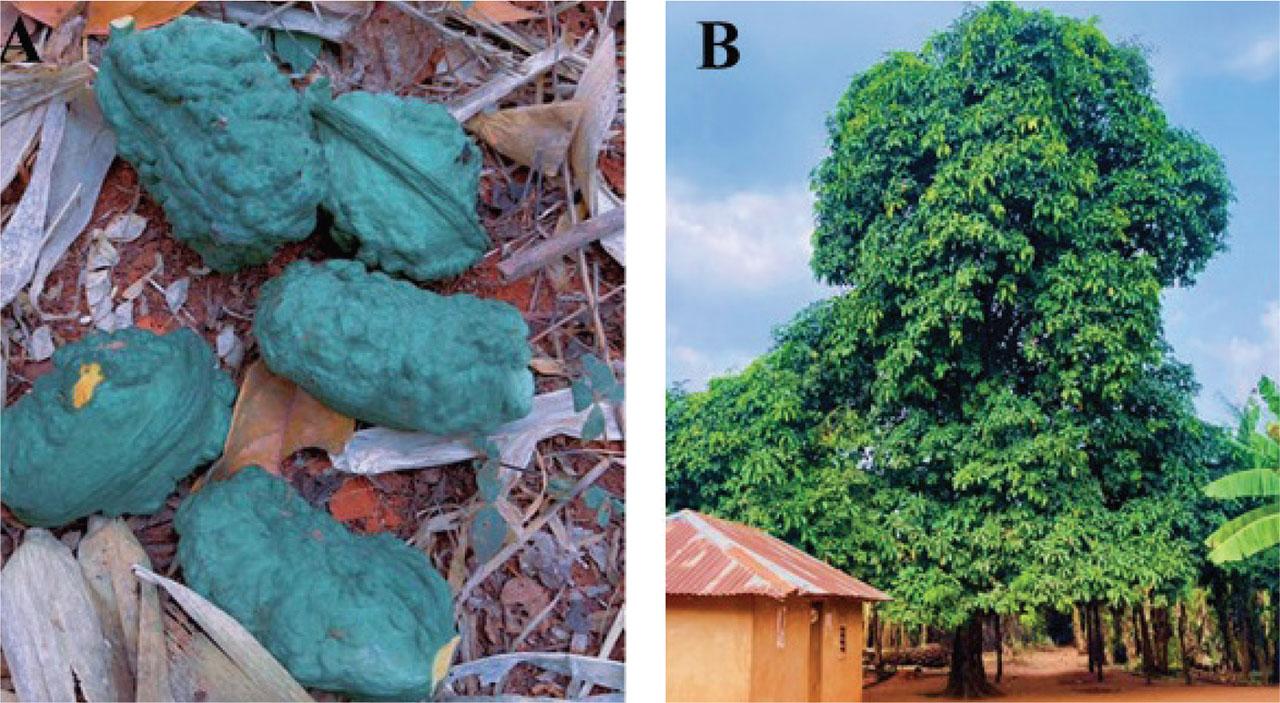

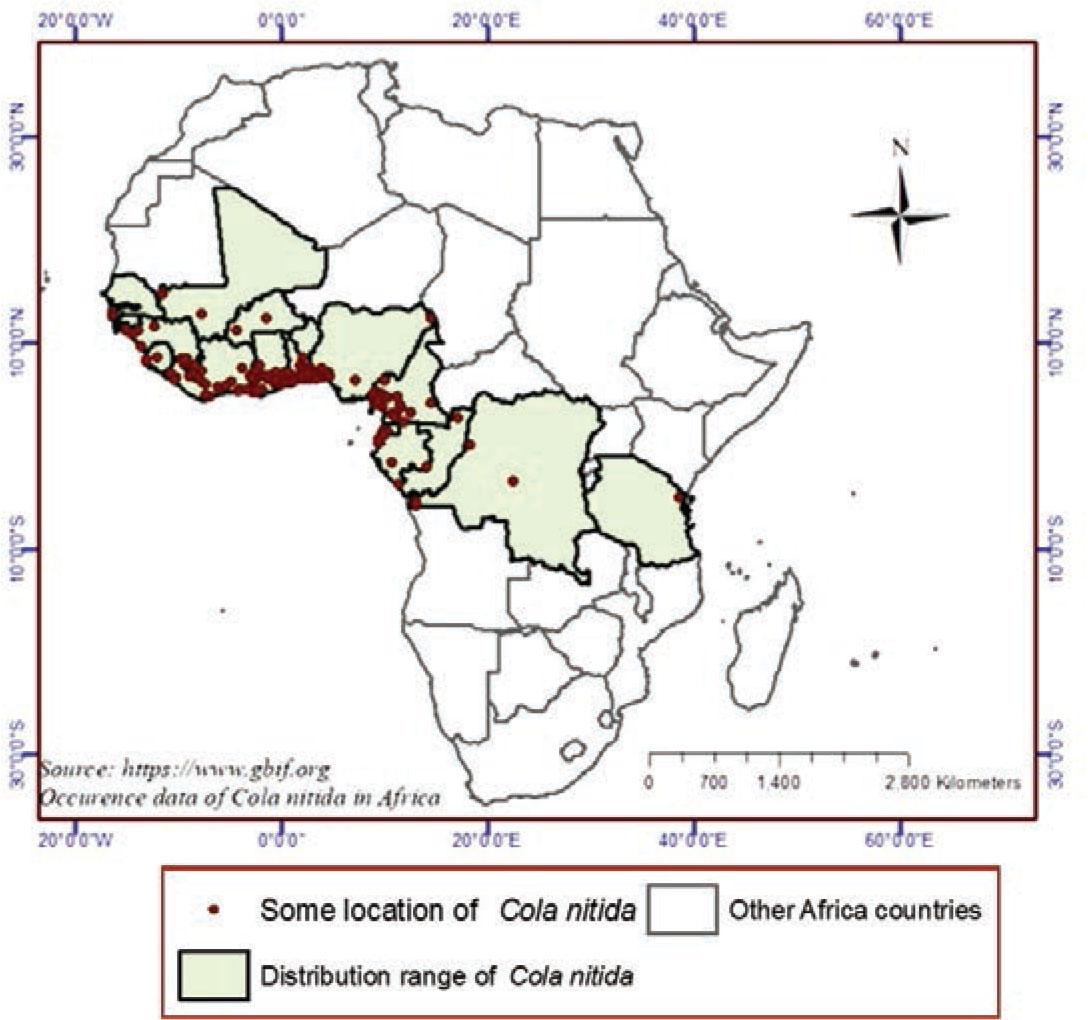

The genus Cola belongs to the family of Sterculiaceae according to the classical classification (Akouègninou et al., 2006) or the family of Malvaceae according to the phylogenetic classification. It includes 125 species (Adebola, 2011). Cola nitida (Figure 5) is one of the most used species of the genus Cola. The Cola nitida species is known by different local names depending on the regions where it is grown or used. Table 1 presents some local names of cola nitida in Africa. The species was distributed throughout the west coast of Africa from Sierra Leone to Benin. (Adebola, 2011). The cultivation of C. nitida was introduced to East Africa through Nigeria, Cameroon, and Congo (Opeke, 1992). The species is cultivated throughout the Gulf of Guinea countries and introduced elsewhere in tropical and subtropical regions (Figure 6). The species of the genus Cola are generally found in tropical lowland forests where rainfall lasts eight months or more and the temperature is between 23 and 28°C. The preferred annual precipitation for Cola species is approximately 1700 mm. However, C. nitida can grow with an annual rainfall of 1200 mm. The species requires a warm and humid climate with distinct wet and dry seasons. However, it can also be cultivated in forest-savannah transition zones (Opeke, 1992).

A: pod of C. nitida; B: species of C. nitida in a home garden in southern Benin (Source: Isabelle E.T. Tokannou).

Occurrence of C. nitida in Africa (GBIF, 2023) realized by Isabelle E.T. Tokannou.

Some local names of C. nitida in Africa (Adapted from Akouègninou et al., 2006; Lim, 2012).

| Local name | Countries | Ethnic group |

|---|---|---|

| Golo | Benin | Adja and Fon |

| Goro | Benin | Bariba, Dendi, Djerma, Peuhl |

| Gbaoundja | Benin | Fon |

| Colatier | Benin; Côte d’Ivoire | Français |

| Toloi | Sierra Leone | Kpaa Mende |

| Oussé | Ghana | Ashanti |

| Obi gbanjȃ | Benin | Yoruba, Nagot |

The flowering of Cola nitida occurs sporadically throughout the year. The peak is observed between August and September (Adebona, 1992). The species have two fruiting seasons: a primary fruiting season from October to January and a smaller one between July and August (Ndubuaku et al., 2015).

C. nitida can be propagated by direct sowing (Mbété, 2007). The primary constraint to propagation by direct sowing is slow seed germination due to prolonged seed dormancy (Legnate et al., 2010). To bypass this constraint, Cola nitida can be propagated by layering (Mbété et al., 2011) or cuttings (Sery et al., 2019). To reduce the germination time of C. nitida, Legnate et al. (2010) showed that dormancy could be lifted by keeping the seed in a humid atmosphere for 45 days after harvest. Gbedie et al. (2017) showed that cutting the end of the Cola nut about 1 cm from the opposite side of the hilum, then soaking it in water for 24 hours or scarifying the Cola nut and soaking it in water for 48 hours, resulted in a germination rate of 93.94% at 84 days after sowing. In Nigeria, Hammed et al. (2019) recently demonstrated how nut color and cotyledon excision percentage affect the germination time of C. nitida seeds. For example, 50% excision of the embryonic part of the cotyledon of white and pink nuts gave a good germination time (5 weeks after sowing). The authors also showed that the higher polyphenol content of C. nitida nut is one of the causes of its slow germination. Cutting the nut before germination reduces the polyphenol concentration and facilitates the lifting of dormancy. The success of C. nitida germination rate also depends on soil type. According to Mukah et al. (2022), seeds of C. nitida could germinate fast when the germination substrate used is river soil or vegetable soil. To remedy the slow growth of C. nitida seedlings in plantations, Ugioro et al. (2021) showed that fortnightly application of gibberellic acid at low concentration (50 mg/L) on red-colored Cola nitida seed could improve seedling growth.

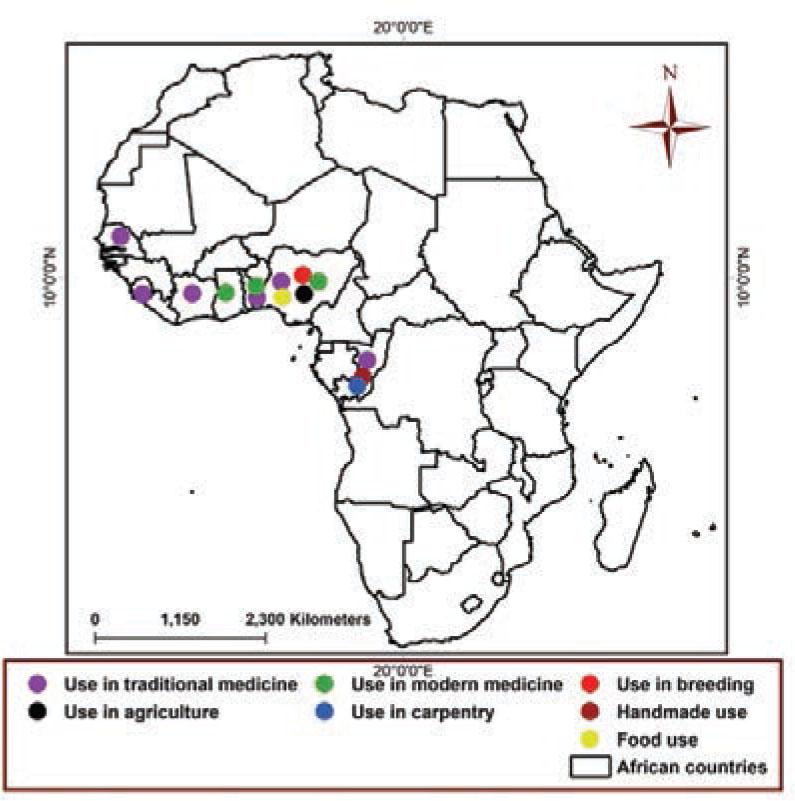

Cola nitida nuts are widely cultivated and used in many African countries (Figure 7) because they contain caffeine and theobromine, two powerful stimulants that neutralize fatigue (Table 2), suppress thirst and hunger, and enhance intellectual activity (Aiyeloja & Bello, 2006). In some African countries such as Benin and Nigeria, for example, cola nuts are culturally used for dowry ceremonies or to seal a bond of friendship between two families or communities (Dah-Nouvlessounon et al., 2015). Cola nuts at a wedding symbolize fertility, productivity, prosperity, consent, and the desire for union (Savi et al., 2019). In Congo Brazzaville, C. nitida nuts are a spiritual meal during traditional ceremonies and rituals. They are also used as a symbol of communion in most traditional ceremonies (Boukoulou & Mbété, 2010).

Some variations in the use of C. nitida in certain African countries.

Medicinal use of C. nitida.

| Plant part | Indications | References |

|---|---|---|

| Nut | Hypotension | |

| Children’s ossification | Boukoulou & Mbété, 2010 | |

| Snake bite | ||

| Antibiotic manufacturing | Dewole et al., 2013; Indabawa & Arzai, 2011; Afolabi et al., 2020 | |

| Stimulant | Aiyeloja & Bello, 2006; Boukoulou & Mbété, 2010 | |

| Nervous system diseases | Lim, 2012 | |

| Improves vision | Igwe et al., 2007 | |

| Cardiovascular diseases | Lim, 2012 | |

| Bark | Diarrhea | Dah-Nouvlessounon et al., 2015 |

| Dysentery | ||

| Antibacterial activity | Adeniyi et al., 2004 | |

| Urinary tract infection | Dah-Nouvlessounon et al., 2015 | |

| Hernia | Dah-Nouvlessounon et al., 2015 | |

| Leaves, bark and root | Stomach aches | Dah-Nouvlessounon et al., 2015 |

| Root | Diabetes | Dah-Nouvlessounon et al., 2015 |

| Difficult childbirth | ||

| Leaves and nut | Cough | Dah-Nouvlessounon et al., 2015 |

| Female sterility | Dah-Nouvlessounon et al., 2015 | |

| Early menopause | ||

| Bark and nut | Menses | Natabou, 1991 |

| Aphrodisiac | ||

| Leaves | Asthma | Lebbie & Guries, 1995 |

• Antibacterial properties

Cola nitida bark contains numerous secondary metabolites dominated by polyphenolic compounds. The presence of these compounds gives C. nitida bark an antibacterial effect on Staphylococcus strains (Dah-Nouvlessounon et al., 2015). In addition, methanol and water-soluble fractions of C. nitida seeds possess antibacterial activity on Staphylococcus aureus (Indabawa & Arzai, 2011). C. nitida seeds or bark are therefore crucial for the manufacture of potent drugs for the treatment of infections caused by test organisms such as Bacillus cereus, Serratia marcescens, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Proteus vulgaris (Obey & Anthoney, 2014).

• Antidiabetic properties

C. nitida nuts are traditionally used in Nigeria to treat and manage diabetes (Oboh et al., 2014). C. nitida nuts are rich in caffeine, theobromine, kolanin,

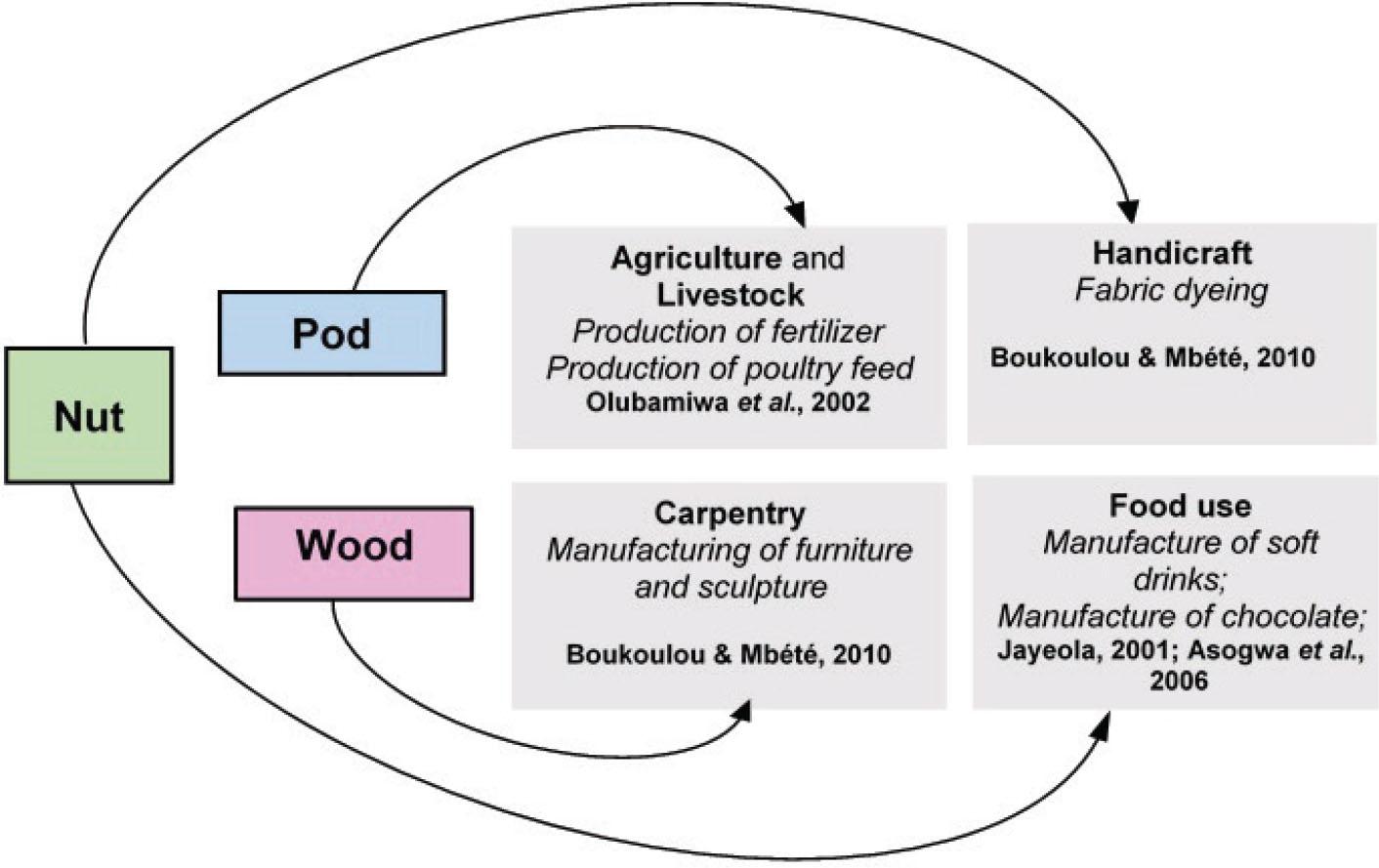

C. nitida nuts are very useful in local and international food industry markets (Figure 8). The nuts are used in the production of cola drinks. C. nitida pods can make poultry feed, liquid soaps, or organic fertilizers (Adedokun et al., 2012). The seeds could also be used to make cola wine, cola soda (Asogwa et al., 2006), and cola chocolate (Adedokun et al., 2012). The indelible juice of cola nut is also increasingly used in textile industries. Besides the nut’s uses, C. nitida wood can be used in carpentry and joinery. It can make luxury furniture and sculptures (Boukoulou & Mbété, 2010). Wood also makes excellent fuel for local people (Lim, 2012).

Other uses of C. nitida.

C. nitida also has a significant economic value for local African communities. The primary economic importance of C. nitida is related to its nuts, which are commercialized on local and international markets (Jayeola, 2001). The commercialization of C. nitida nuts contributes to the income of various African households. For example, the average selling price of the C. nitida nut in southern Benin markets is between $2 USD and $3 USD per kilogram of nuts. Sustainable species production will, therefore, contribute to increasing income generated from the species exploitation. In Congo Brazzaville, a bucket of 10 kg of C. nitida nuts is purchased in the production areas for $3 USD to $5 USD. It is resold to semi-wholesalers at $20 USD for red cola nuts and $21 USD for white cola nuts (Boukoulou & Mbété, 2010). To promote the species’ sustainable production, future research should aim to identify the key stakeholders involved within each producing country and establish an innovation platform to facilitate collaboration and propose new approaches to improve the species’ value chain.

C. nitida nuts contains approximately 10.06% ± 0.75 of protein, 8.30% ± 0.78 of reducing sugar, 12.46 % ± 0.80 of water, 0.20% of fat, 4.31% ± 1.02 of crude fiber, 0.34% of potassium and 0.04% of phosphorus (Dah-Nouvlessounon et al., 2016; Odebunmi et al., 2009). According to Jayeola (2001), C. nitida nuts have a nutritional composition consisting of protein (8.90%), fat (0.92%), and 4% ash by dried powder sample. Fresh nuts contain approximately 69% of carbohydrates, and 18% of crude fat (Arogba, 1999). The nut is also rich in catechin (27–37 g/kg), caffeine (18–24 g/kg), epicatechin (20–21 g/kg) (Atawodi et al., 2007). The species’ bark is rich in alkaloids (0.80%), saponins (0.40%), tannin (0.77%) and glycosides (0.43%) (Kanoma et al., 2014). Future work should be carried out to see whether the nutritional value and chemical properties of C. nitida nuts vary according to the climatic and edaphic parameters of the species’ growing zone.

The production of C. nitida in agroforestry systems (Figure 9) includes a method that could promote its conservation. C. nitida can share the same habitat with Coffea canephora (Pierre ex A. Froehner), Theobroma cacao (L.), and Raphia hookeri (G.Mann & H.Wendl.) (Oke & Odebiyi, 2007). When these species are intercropped within C. nitida plantations, the C. nitida tree provides shade over the plantation. It constitutes another source of income for the producer (food and money) (Oladokun & Egbe, 1990). The production of C. nitida in agroforestry systems provides fertile soil, an appropriate microclimate for soil conservation, the provision of firewood, as well as immediate and diversified economic benefits for the farmer (Ekanade & Egbe, 1990). Future research endeavors on C. nitida in Africa should determine factors affecting its productivity in agroforestry systems. These investigations will improve the species’ productivity within agroforestry systems, encouraging local communities to integrate the species within their farms.

C. nitida in an agroforestry system in southern Benin (Source: Isabelle E.T. Tokannou).

Cola nitida shows excellent morphological diversity (Figure 10), and this variability is attributable to a wide range of factors such as environmental factors (soil type, climatic condition), probable fertilizer input, and phenotypic plasticity. Dah-Nouvlessounon et al. (2016), Onomo et al. (2006), and Adebola & Morakinyo (2006) reported, for example, an essential morphological variability (tree shape, leaves aspect, fruits aspect, nuts aspect, flowers characteristic) between C. nitida populations respectively in Benin, Cameroon, and Nigeria.

Morphological variability between C. nitida nuts (Source: Isabelle E.T. Tokannou).

There is also significant genetic variability within C. nitida African populations (Ouattara et al., 2018). Akinro et al. (2019) and Ouattara et al. (2022) revealed through DNA-based molecular markers such as RAPD and Single Nucleotide Polymorphism markers that there is a high rate of polymorphism within C. nitida populations in Nigeria. This intra-specific genetic variability may be related to inherited (genetic) or non-inherited (environmental condition) traits (Adebola et al., 2002). Therefore, the environment may play an essential role in the expression of variability within C. nitida populations. Further investigations on the genetic characterization of C. nitida are needed to critically examine the genetic differences along its native distribution range (e.g. at a region, sub-region, or country level).

Cola nitida faces several attacks from insects or plants that can harm its different organs. These pests of C. nitida, include: vascular parasitic plants of the Loranthaceae family, especially: Phragmanthera capitata (Spreng.) Balle; Globimetula cupulata (DC.) Danser; Tapinanthus bangwensis (Engl. & K.Krause) Danser; Tapinanthus globiferus (A.Rich.) Tiegh.; Tapinanthus belvisii (DC.) Danser; Globimetula braunii (Engl.) Danser (Ahamide et al., 2015). These parasites are linked to C. nitida by a veritable structural and physiological bridge, consisting of an absorption system that enables them to benefit from C. nitida’s water and mineral substances (Ahamide et al., 2015). During the storage, the nut of Cola can also be attacked by weevils (Balanogastris kolae (Desbr.), Paremydica insperata (Faust); certain insects of Coleoptera genus; diptera (Pterandrus colae (Silvestri)), and fungi such as Aspergillus niger var. niger, which can cause considerable loss of nuts (Dembele et al., 2008). Farmers often resort to different traditional conservation methods to overcome pest infestations of nuts, such as burying the nuts in termite mounds and soil and wrapping them in Thaumatococcus daniellii (Benn.) Benth. leaves (Pedaliaceae). Some farmers also used pesticides belonging to the families of organochlorines, organophosphates, and pyrethroids (Agbeniyi, 1999). However, organochlorine pesticides are not recommended (Biego et al., 2009). Some cultural methods have also been developed and recommended to reduce the impact of these pests on C. nitida nuts (Asogwa et al., 2006). These methods involve:

early harvesting of mature pods (which significantly reduces the level of damage caused by the cola weevil);

eliminating fallen pods (the pods on the tree at the end of the primary fruiting season and immature pods produced between crops);

burying the shells that house developing larvae;

cleaning weevil-infested nuts before and during storage and using edible salt and wood ashes to protect fresh and stored cola nuts from fungal diseases.

Agwu (2020) reported that climate change significantly influences the growth and anatomical characteristics of C. nitida. According to these same authors, future climate projections under the RCP 8.5 and 4.5 climate scenarios from the HadGEM2-ES and CNRM-CM5 climate models have shown a substantial decrease in areas suitable for cultivating C. nitida in Nigeria. Therefore, rural producers should be encouraged to propagate more C. nitida in the agroforestry system to sustain the ecosystem services provided by the species to local populations.

Moreover, despite the socioeconomic importance of Cola nitida both at the country level and in international markets, the production of C. nitida nuts faces several challenges in West Africa (Mbété et al., 2011). Production of C. nitida needs to be improved due to the lack of high-performing plant material, slow germination, and difficulties in accessing reasonable technical assistance (Mbété et al., 2011). The factors influencing the survival rate and sustainable production of C. nitida include the type of genotype and abiotic parameters (Paluku et al., 2018). The lack of information on improved production technologies is, therefore, a challenge to the species’ sustainable use. The infestations of C. nitida nuts by pest diseases, and the lack of support for promoting the species’ sustainable production are also obstacles to the development of C. nitida production in Africa (Ndagi et al., 2012).

Another challenge related to the conservation of C. nitida populations in African countries is the over-exploitation of its ecosystem (Savi et al., 2019). There is a decline in the species’ populations in its natural ecosystems (Ndagi et al., 2012; Savi et al., 2019; Agwu et al., 2022). This loss could be due to the fragmentation of the species’ natural habitats, primarily caused by anthropogenic activities. The decline of C. nitida could also be due to the adverse effects of climate change on the species distribution (Agwu et al., 2022) and farmers’ lack of willingness to actively propagate it in natural ecosystems and agroforestry systems. Yet, local communities have also adopted several conservation strategies to ensure the sustainable conservation of C. nitida populations. According to Savi et al. (2019), one of the strategies adopted by local communities in Benin to protect the species in their home gardens was to decorate the tree with a white flag spotted with animal blood. This emblem on the species symbolized a prohibition on cutting its adult stems.

Socio-economic factors, ethnic affiliations, and beliefs are among the determining factors influencing the conservation and cultivation of a species (Donou Hounsode et al., 2016). However, although the research has highlighted a decline in the remaining stands of C. nitida in both natural habitats and farmlands (Agwu, 2020; Savi et al., 2019; Dah-Nouvlessounon et al., 2016), there is a lack of documented scientific work on the key factors that motivate local people to conserve or cultivate the species. Examining these factors will provide insights into the factors determining the unwillingness of certain producers to be involved in the species’ cultivation activities, even though they reside in areas suitable for cultivating the species.

Furthermore, to ensure the sustainable production of Cola nitida in African countries, future research must focus on identifying innovative agricultural methods that can improve the species’ productivity. It is also crucial to propose appropriate technical approaches for successful seed germination and the fast growth of seedlings in plantations (Sery et al., 2019). However, few research works have addressed for example, the effect of different doses and different types of fertilizers on the growth of C. nitida seedlings. Could applying fertilizer improve the early growth performance of Cola nitida seedlings? What type of fertilizer and dose would be conducive to a better growth pattern for this species? More information on the species’ production itineraries is needed, which could be essential in improving cultural practices regarding C. nitida production.

Additionally, C. nitida has slow growth and late reproduction (Mbété et al., 2011). However, few studies exist on the determinism of this slow growth. It would be interesting to assess if such slow growth is specific to the species’ physiology or if it varies depending on abiotic parameters such as competition with weeds, nutrition, soil fertility, or the depth of planting holes. In-depth physiological and ecophysiological studies on the species are also critical to better assess the effect of competition with weeds or other species on the species’ development in plantations, especially at the juvenile stage.

Several studies have emphasized the cultural importance of C. nitida for local populations (Dah-Nouvlessounon et al., 2015; Ahamide et al., 2015; Savi et al., 2019), while others have indicated a decline in the species populations (Nyadanu et al., 2020; Dah-Nouvlessounon et al., 2016). Nevertheless, the consequences of this population decline on the sustainability of cultural rituals linked to the species’ utilization still need to be documented. What would be the impact of the decline of the species’ populations on the sustainability of the cults associated with the species’ use? Could other species replace the species C. nitida for the same rites within these cults? What is the degree of involvement of the followers of the cults associated with the use of the species in actions towards the species’ conservation and propagation? These are some questions that still require answers.

The socio-economic importance of C. nitida has been demonstrated in several African countries. However, more information is needed on the constraints linked to the conservation of the species in agro-forestry systems. What is the perception of local producers regarding the conservation of C. nitida in agroforestry systems? What types of agroforestry systems would be suitable for the better valorization of the species? Is the productivity of the species in agroforestry systems a function of variety, genotype, or morphotype? What is the type of Cola nitida agroforestry system that best contributes to improving the living conditions of producers? What factors determine the socio-economic and biophysical performance of Cola nitida agroforestry systems?

In addition, based on the publications on C. nitida from 1990 to 2022 in Africa, 7% of publications highlighted research works on the morphological and genetic variability of the species. These works have shown significant phenotypic variability within and between meta-populations of the species. However, only some scientific works have been interested in the factors that caused the expressions of this phenotypic variability within and between C. nitida populations. Understanding the determining factors of this phenotypic variability of the species between and within African countries is essential for developing further conservation and domestication programs of C. nitida. These studies could help to identify individuals or populations with desirable characteristics such as resistance to drought, resistance to pest attacks, tolerance to hydromorphic, growth performance, precocity of the age of reproductive maturity, and the regularity of flowering, etc. Furthermore, in some producing countries, such as Benin, more information is needed on the different genotypes of C. nitida seeds. However, these studies could serve as a reference for developing work on the genetic improvement of the species.

It would also be essential to update research works on the species’ phenology and ecology. Most of the research describing the phenology and ecology of Cola nitida dates back over thirty years. Given the current climate variability, it would be crucial to update this data, as it forms the fundamental information for updating the technical production sheets of C. nitida. These data can also help identify, within each African country, the current suitable areas for its production.

This systematic review provides an overview of the research carried out in Africa on C. nitida from 1990 to 2022, highlighting research perspectives for its conservation in natural ecosystems and agroecosystems. The interest of researchers in promoting the value chains of C. nitida in Africa has increased significantly since 2013. Several studies have been carried out on the species, including on the socio-economic importance of its organs, strategies for controlling pests and pesticide contamination, the nuts’ conservation methods, and the species’ adaptation to climate change. However, some aspects still need to be documented. Future research endeavors need to identify innovative agroforestry technologies for the sustainable production of C. nitida. These technologies should optimize cultivation practices and productivity. In-depth studies on the species could also focus on breeding for genetic improvement, including a selection of genotypes for both productivity and drought stress tolerance.