In many countries, entrepreneurship is now seen as an engine for economic growth and an essential indicator in making policies concerning industry development (Adekiya and Ibrahim, 2016; Urbano, et al., 2019). Particularly, in a transition economy such as Vietnam, entrepreneurship is increasingly critical to job creation, poverty alleviation and wealth creation. The growing importance of entrepreneurship in national development has been recognized and reflected in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) targets 4.4 and 8.3. Specifically, the goal of SDG 4.4 is to dramatically increase the number of young people and adults with appropriate entrepreneurship skills. Concurrently, SDG target 8.3 is intended to promote development-oriented policies that support entrepreneurship.

As entrepreneurship has grown and expanded around the world, it has become a salient research topic not only in developed countries, but also in developing ones in recent decades. Most studies to date have focused on groups of factors that have been traditionally considered determinants for an individual entrepreneurial decision. These groups of factors include contextual factors such as family support (Shirokova, et al., 2016) and education system and culture (Do Nguyen and Nguyen, 2023), individual factors that include personality traits such as locus of control, tolerance for ambiguity, need for achievement (Barba-Sánchez and Atienza-Sahuquillo, 2018), and entrepreneurial alertness (Thai and Mai, 2023), and socio-demographic factors (e.g., age, gender, and educational level).

Regarding the contextual factors, family support has been proved to have both positive and negative impacts on entrepreneurial intention (EI; Sieger and Minola, 2017; Shirokova, et al., 2016). In addition, the positive role of entrepreneurship education in promoting students’ intention to start a business has been confirmed in studies from many countries such as the USA, European countries, China, Brazil, Malaysia, Nigeria, Zambia (Liñán, et al., 2011; Adekiya and Ibrahim, 2016), and Vietnam (Do Nguyen and Nguyen, 2023). Nonetheless, only a few studies have looked at the effect of culture on entrepreneurship (Adekiya and Ibrahim, 2016; Koçoğlu and Hassan, 2013). Previous studies predominantly utilized Hofstede’s cultural model (Kayed, et al., 2022; Oh, et al., 2016). However, when examining EI and behavior, Hofstede’s national culture framework requires further clarification at the individual level to ensure alignment with personality traits and gender factors. To evaluate the impact of culture on EI in this study, we applied the Appropriateness, Consistency, and Effectiveness (ACE) model, as used in the research by De Pillis, et al. (2007) and Sajjad and Dad (2012), integrating personality traits and gender as additional factors influencing EI.

For decades, personality traits have received wide scholarly attention. Many researchers have analyzed the differences in personality between entrepreneurs and non-entrepreneurs (Duong, 2023). They found that certain character traits are required as preconditions for entrepreneurship (Utsch and Rauch, 2000). Some of the key prerequisites include a high need for achievement, internal control locus, moderate risk-taking orientation, a high level of ambiguity tolerance, and a high level of self-confidence and innovation (Barba-Sánchez and Atienza-Sahuquillo, 2018). It has been proved that these traits have a profound influence on an individual’s intention to start a new venture (Krueger and Carsrud, 1993; Thomas and Stephen, 2000; Acharya and Berry, 2023).

A number of studies have shown that socio-demographic factors may explain EI (Nguyen, 2018; Dubey and Sahu, 2022). These studies have provided empirical evidence to support the significance of the difference in entrepreneurial attitude and intention between males and females and between students with different educational backgrounds (Rubio-Banon and Esteban-Lloret, 2016; Thu and Le Hieu, 2017). However, there is still a lack of entrepreneurship studies in the context of a transition economy like Vietnam. The moderating role of gender on the link between the predictors and EI has not been studied. This paper aims to analyze the influence of personality traits and culture on the EI of students, with a focus on gender as a moderating variable.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 1 is the introduction to the topic. Section 2 discusses current studies on EI and develops research hypotheses. Section 3 presents the methodology of this research. Findings and discussions are presented in Section 4. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper with the implications and limitations.

Until now, no consensus has been reached on the definition and meaning of the term “entrepreneurship.” However, many scholars have seen it as a dynamic process created and managed by an individual who seeks to create new value to satisfy a particular market need (Clark and Harrison, 2019; Liñán and Fayolle, 2015). Similarly, Kuratko and Audretsch (2009) point out that entrepreneurship is a process through which an individual exploits an opportunity and creates value. In the same vein, it is also described as a process that entrepreneurs engage in to create and grow enterprises to provide new products or services or add value to existing products or services.

From such a behavioral approach, entrepreneurship can be seen as the result of the interactions of the perceptions, attitudes, and intentions of individuals. Thompson (2009) argues that EI precedes any attempt at entrepreneurship. It means that entrepreneurship can be defined as the outlook on self-employment or the desire to own a business.

The need for achievement (ACH) is the drive of a person to succeed. The need for achievement can be described as a struggle against challenging tasks. People with a high need for achievement tend to be more eager for success than those with a lower need for achievement. It is shown that those who want to be seen as entrepreneurs are more likely to establish successful businesses in competitive markets (Murray, 1983). Terpstra, et al. (1993) stated that the need for achievement consists of the desire to be successful, the tendency to take calculated risks, and the desire for concrete feedback. Lee and Williams (2007) claimed that the need for achievement motivates a person to face challenges in the hope of attaining success and excellence. McClelland (1987) argued that the need for achievement affects EI. He classified people who have a high need for achievement as people who have a strong desire to be successful. People who have high scores on the need for achievement scale prefer to take risks and responsibility and are interested in observing the results of their decisions. A person with a high need for achievement is also more self-confident, enjoys taking risks, researches his environment actively, and is very much interested in concrete measures of how well he is doing (McClelland, 1987). However, according to Kristiansen and Indarti (2004), a low need for achievement is associated with low expectations, failure, low competence, self-blame, and little inspiration. Although much research has been conducted to find the correlation between ACH and EI, for example, Carsrud and Brannback (2014) and Pérez-Fernández, et al. (2022), the relationship between ACH and EI still demands exploration, which can bring more benefit for the theoretical approach.

Various researches such as Gürol and Atsan (2006), Hansemark (1998), and Johnson (1990) have confirmed the significant effects of the need for achievement on EIs. McClelland (1961) claims that people with higher desires and ambitions to be successful (need for achievement) have a higher potential to become entrepreneurs. Recently, Pérez-Fernández, et al. (2022) confirmed the positive impact of ACH and EI in the context of social network mechanism. Comparative studies support McClelland’s theory (Johnson, 1990; Hansemark, 1998). For example, Hansemark (1998) surveyed a group of students who participated in an entrepreneurship program to compare their need for achievement and locus of control of reinforcement with those of a control group of non-participants. The findings showed that participants in the entrepreneurship program are developing a higher level of need for achievement and a greater internal orientation of the control locus. Gürol and Atsan (2006) found that entrepreneurially inclined students who had a higher need for achievement wanted to establish their own businesses. Johnson (1990) revealed that the need for achievement is linked to a strong EI. Moreover, Rauch and Frese (2007) demonstrated that there is a positive correlation between the need for achievement and entrepreneurial behavior in their meta-analysis.

Based upon the aforementioned studies, this study tests the following hypothesis:

H1: Need for achievement positively influences students’ EI.

According to Kirzner (1999), entrepreneurial alertness means the recognition and development of new opportunities. It is an essential trait of entrepreneurs (Tang, et al., 2012). In further developing the boundaries of alertness, Tang, et al. (2012) argue that an essential component of alertness is the aspect of judgment. This component focuses on evaluating new changes in the market and deciding if they reflect a business opportunity with profit-making potential (Tang, et al., 2012).

Alertness helps some individuals to be more aware of changes and opportunities in the market (Kirzner, 1999). Moreover, alertness supports entrepreneurs to enhance their sniffing ability to help them have the capability of identifying gaps in the market (Kirzner, 1999; Awwad and Al-Aseer, 2021). This trait enables people to organize and interpret information related to the development of new opportunities (Awwad and Al-Aseer, 2021). Furthermore, alertness includes creative and imaginative action and may “impact the type of transactions that will be entered into future market periods” (Kirzner, 2009). Urban (2020) found that the core of alertness includes searching information, cognitive ability, personality factors, environment, social networks, and experience. Entrepreneurial alertness causes entrepreneurs to explore and take advantage of new opportunities.

Kaish and Gilad (1991) conducted the first empirical test on the theory of alertness and provided empirical support of it. They found that different entrepreneurs used information in different ways, and some of them became more alert to opportunities than others. Those alert individuals have a “unique preparedness” in scanning the environment and are ready to discover opportunities. Therefore, this study hypothesizes as follows:

H2: Entrepreneurial alertness positively influences students’ EI.

Culture is defined as a “collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from another” (Hofstede, 2003). Meanwhile, Hayton and Cacciotti (2014) define the concept of culture as values, beliefs, and expected behaviors that are sufficiently common across people within (or from) a given geographic region. Entrepreneurial culture is the value, behaviors, skills of communities or individuals who participate in creativity and innovativeness (Danish, et al., 2019; Mukhtar, et al., 2021)

The effect of cultural dimensions on EI has been examined in many studies. Most of the studies used Hofstede’s culture model, while others used the ACE model of persuasion proposed by Reardon (1991).

The ACE model of persuasion was derived from an extensive body of communication research concerning entrepreneurial behavior and highlights cultural factors that can act as a precursor to entrepreneurial intent. In the ACE model, perceived appropriateness is the degree to which entrepreneurship is perceived as suitable and recognized by others in society as an appropriate career. Perceived consistency is the degree to which entrepreneurship is a good fit with one’s self-concept. Perceived effectiveness is defined as the degree to which a career in entrepreneurship is perceived as the capability to achieve one’s desired outcome or lifetime goals. To the extent that people have internalized positive impressions about ACE of entrepreneurship, they are likely to convert these impressions into the intention to start a business (De Pillis and Reardon, 2001).

As argued by Bandura, et al. (2001), behaviors and attitudes are developed in part by observing and learning from others. This social learning can take place via one individual observing another or via messages in the media (Bandura, et al., 2001). Therefore, it stands to reason that if entrepreneurs are portrayed positively in the mass media and spoken of favorably by individuals in society, these factors are likely to have a positive influence on their beliefs, values, and attitudes toward entrepreneurship and vice versa (Adekiya and Ibrahim, 2016). In support of this argument, Karayiannis (1993) reasoned that social and cultural approval by a given society contributes to the growth of entrepreneurial activity when the values of that society reward entrepreneurship. Societal disapproval of entrepreneurship impedes this growth. Lastly, Ismail, et al. (2012), using empirically supported evidence, discovered that cultural predictors of appropriateness significantly influence the decision to become seasoned entrepreneurs in Malaysia. Entrepreneurial culture can help to improve the level of confidence and creativity of students (Bogatyreva, et al., 2019; Mukhtar, et al., 2021). Mukhtar, et al. (2021) confirmed that entrepreneurial culture supports student’s awareness to find the opportunities to become entrepreneurs instead of being workers. These arguments lead to the formulation of the following hypotheses in the Vietnamese context.

H3: Perceived appropriateness positively influences students’ EI. H4: Perceived consistency positively influences students’ EI. H5: Perceived effectiveness positively influences students’ EI.

Regarding the effect of gender on entrepreneurship, research has revealed significant differences between men and women in terms of the levels of participation in business, orientations, motives, and alertness to business opportunities (Pérez-Pérez and Avilés-Hernández, 2016).

Gender has been used in many studies on entrepreneurship either as a controlling variable or a mediator. In this study, we assumed that gender moderates the relationship between personality traits, cultural predictors, and EI of the students. Therefore, we proposed these hypotheses.

H6: Gender moderates the link between the need for achievement and students’ EI. H7: Gender moderates the link between entrepreneurial alertness and students’ EI. H8: Gender moderates the link between perceived appropriateness and students’ EI. H9: Gender moderates the link between perceived consistency and students’ EI. H10: Gender moderates the link between perceived effectiveness and students’ EI.

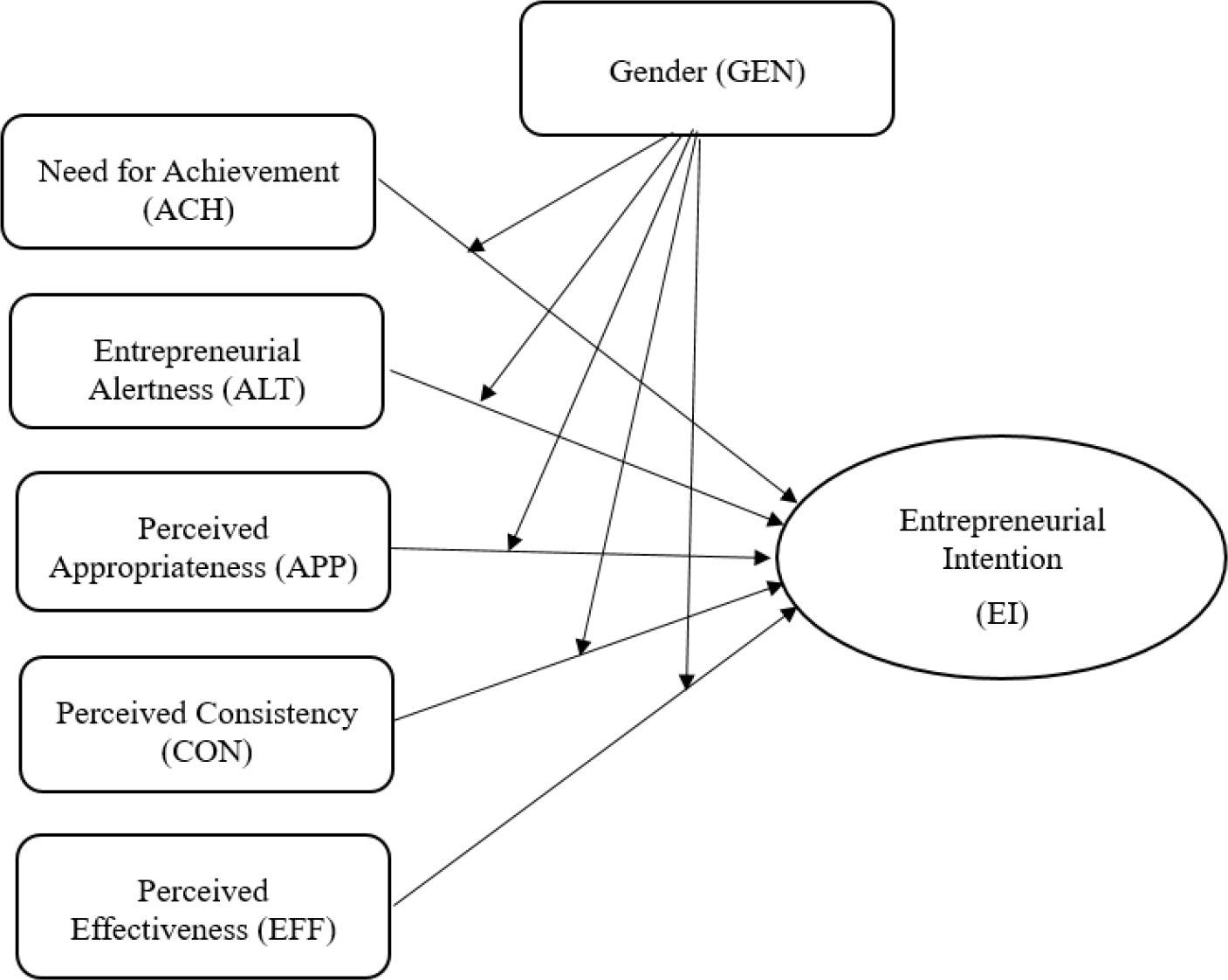

A research model was developed to examine the influence of personality traits and cultural dimensions on the EI of Vietnamese students as the hypotheses in Section 2 indicated (see Figure 1). The dependent variable in this research model was EI.

Type of Agency Problem

(Source: Authors’ own research)

For the variables to measure personality traits, we chose the need for achievement and entrepreneurial alertness because they are two prominent personality traits that have been confirmed in previous studies on entrepreneurship in both developed and developing countries. The other three independent variables were the dimensions in the ACE model (Reardon, 1991), including perceived appropriateness (ACH), perceived consistency (CON), and perceived effectiveness (EFF). Gender was added to the model as a moderating variable.

The constructs of this research were adapted from previous studies related to the antecedents of EI. All items were measured by using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.

In this study, EI of students is the dependent variable. EI was measured on five items adapted from the study of Liñán and Chen (2009), which created an EI questionnaire (EIQ) and analyzed its psychometric properties. Liñán and Chen (2009) tested the EI model on a 519-individual sample from Spain and Taiwan and then confirmed the satisfactory results for the model.

The independent variables include two factors of personality traits and three factors of culture. Personality traits have two dimensions, which are the need for achievement (seven items) and entrepreneurial alertness (three items). The measurement items were adopted from the studies of Çolakoğlu and Gözükara (2016), Karabulut (2016), and Mueller and Thomas (2001). Both Çolakoğlu and Gözükara (2016) and Karabulut (2016) tested the impact of personality traits on the attitudes of university students toward entrepreneurship in Turkey. However, Mueller and Thomas (2001) conducted a cross-study over nine countries, including the USA, Canada, China, Ireland, and some European countries (i.e., Spain, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Slovenia, Germany), to test the impact of locus of control and innovation on EI.

In this research, cultural predictors include perceived appropriateness (seven items), perceived consistency (four items), and perceived effectiveness (eight items). The items on these constructs were adopted from the original work of De Pillis and Reardon (2001) and Adekiya and Ibrahim (2016). In the work of Adekiya and Ibrahim (2016), the three dimensions of culture in the ACE model were used to examine the role of culture and entrepreneurship training and development on entrepreneurship intention in Nigeria. Their findings revealed that perceived appropriateness and perceived effectiveness had a positive impact on entrepreneurship intention. Similarly, De Pillis and Reardon (2001) also examined the role of culture, personality, and role models on EI and confirmed the positive relationship among these factors.

Based on the construct measurements of all variables in the research model, the questionnaire was designed and presented in unbiased and straightforward wording, whereby respondents could easily understand the questions and provide the answers based on their perception.

The respondents were university students in Hanoi, Da Nang, and Ho Chi Minh City. The survey was implemented both online and in person. The authors contacted the leaders of student clubs at the universities to distribute the questionnaire through their social networks. Printed questionnaires were distributed in classes that the authors taught.

After 4 months, 945 responses were received, which included the responses of 713 females and 232 males. Over 50% of the respondents were third- and fourthyear undergraduate students. Regarding the major, 740 of the respondents (78.3%) were enrolled in business programs, while 205 of them (21.7%) were non-business students.

In this study, we employed several data analysis methods in AMOS version 20 to check the validity of the data set and the proposed hypotheses. We chose AMOS to run our analysis as this software is suitable for complex research model reflecting the casual relationship between many variables.

Harman’s single factor test was run to check the common method variance problem. Cronbach’s alpha analysis and exploratory factor analysis (EFA) were run to test the reliability, validity, and convergence of the measurement constructs.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was run to test the presumed model on the basis of conventional fit indices, that is, chi-square (χ2), chi-square/df (χ2/df), goodness-of-fit index (GFI), incremental fit index (IFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), comparative fit index (CFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), using AMOS version 20. Structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis was run to test hypotheses in the research model.

The data were analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) and AMOS version 20. The assessment of common method effect was conducted using Harman’s single factor test. According to this test, if the factor analysis results indicate a single factor or if any one general factor accounts for more than 50% of the covariance of the independent and dependent variables, this indicates the presence of a substantial amount of common method variance. In the present study, all constructs were entered for analysis and constrained a single factor.

The Harman’s single factor test results showed that the single factor explained only 25.98% of the total variance, suggesting that the collected data are free from the threats of common method variance.

Furthermore, Cronbach’s alpha analysis and CFA were run to test the reliability, validity, and convergence of the measurement constructs (Table 1). Scales showed moderate to good reliability, with all Cronbach’s alpha values over 0.6. CFA results confirmed the measurement model fit with all acceptable indices (Table 2), and all items of the six constructs were loaded to the hypothesized factors with standardized regression weights higher than 0.5.

Reliability, validity, and convergence of measurement constructs

(Source: Authors’ own research)

| Construct | Cronbach’s alpha | CR | AVE | Item | Loading |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Need for Achievement (ACH) | 0.807 | 0.906 | 0.583 | Ach1 | 0.647 |

| Ach2 | 0.709 | ||||

| Ach3 | 0.811 | ||||

| Ach4 | 0.763 | ||||

| Ach5 | 0.684 | ||||

| Ach6 | 0.792 | ||||

| Ach7 | 0.908 | ||||

| Entrepreneurial alertness (ALT) | 0.741 | 0.838 | 0.637 | Alt1 | 0.664 |

| Alt2 | 0.888 | ||||

| Alt3 | 0.825 | ||||

| Perceived appropriateness (APP) | 0.798 | 0.891 | 0.624 | App1 | 0.755 |

| App2 | 0.811 | ||||

| App3 | 0.781 | ||||

| App4 | 0.659 | ||||

| App5 | 0.920 | ||||

| Perceived consistency (CON) | 0.694 | 0.854 | 0.594 | Con1 | 0.714 |

| Con2 | 0.803 | ||||

| Con3 | 0.745 | ||||

| Con4 | 0.817 | ||||

| Perceived effectiveness (EFF) | 0.844 | 0.918 | 0.584 | Eff1 | 0.790 |

| Eff2 | 0.784 | ||||

| Eff3 | 0.746 | ||||

| Eff4 | 0.809 | ||||

| Eff5 | 0.807 | ||||

| Eff6 | 0.591 | ||||

| Eff7 | 0.730 | ||||

| Eff8 | 0.830 | ||||

| Entrepreneurial intention (EI) | 0.863 | 0.927 | 0.719 | EI1 | 0.872 |

| EI2 | 0.887 | ||||

| EI3 | 0.849 | ||||

| EI4 | 0.816 | ||||

| EI5 | 0.812 |

Model fit statistics of the measurement model

(Source: Authors’ own research)

| - | Obtained value | Acceptable value |

|---|---|---|

| χ2/df | 3.950 | 3–5 |

| GFI | 0.936 | >0.90 |

| TLI | 0.882 | >0.85 |

| NFI | 0.872 | >0.85 |

| CFI | 0.901 | >0.90 |

| RMR | 0.125 | Close to 0 |

| RMSEA | 0.055 | <0.07 |

Table 2 shows that the measurement model has acceptable values. Therefore, it is concluded that the measurement model is suitable for further analysis.

In addition, to check the correlation among factors in the measurement model, Pearson’s correlation analysis in SPSS was used. As Table 3 shows, all factors are positively related to the others, with correlation values ranging from 0.291 to 0.637.

Correlation analysis result

(Source: Authors’ own research)

| - | ACH | ALT | APP | CON | EFF | EI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACH | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| ALT | 0.427** | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| APP | 0.380** | 0.236** | 1 | - | - | - |

| CON | 0.364** | 0.389** | 0.540** | 1 | - | - |

| EFF | 0.291** | 0.314** | 0.561** | 0.637** | 1 | - |

| EI | 0.416** | 0.497** | 0.415** | 0.535** | 0.512** | 1 |

Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

Before running further analysis to test the hypotheses, we checked if our sample followed the normal distribution. Thus, the normality tests were conducted and details are shown in Table 4.

Normality test

(Source: Authors’ own research)

| - | Descriptives | Tests of normality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | Skewness | Kurtosis | Kolmogorov–Smirnova | Shapiro–Wilk | ||||

| Statistic | df | Sig. | Statistic | df | Sig. | |||

| ACH | -0.807 | 1.711 | 0.100 | 945 | 0.085 | 0.950 | 945 | 0.075 |

| ALT | -0.055 | 0.098 | 0.110 | 945 | 0.145 | 0.976 | 945 | 0.275 |

| APP | -0.347 | 0.954 | 0.098 | 945 | 0.095 | 0.974 | 945 | 0.085 |

| CON | 0.092 | 0.832 | 0.113 | 945 | 0.075 | 0.972 | 945 | 0.090 |

| EFF | 0.033 | 0.527 | 0.066 | 945 | 0.215 | 0.990 | 945 | 0.125 |

| EI | -0.258 | 0.787 | 0.103 | 945 | 0.090 | 0.971 | 945 | 0.095 |

Lilliefors significance correction

It is seen in Table 4 that the skewness and kurtosis of all variables are within the acceptable range of -1.96 to 1.96. The p-values of all variables for the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests are higher than 0.05. Therefore, it is concluded that all variables in our sample are normally distributed.

SEM analysis was run to examine how cultural factors and personality traits affect entrepreneurial intention. Table 5 reveals that all five independent variables had a positive impact on entrepreneurial intention as the p-values were smaller than 0.05. Thus, the five hypotheses from H1 to H5 were supported. Among the five factors, entrepreneurial alertness (β = 0.276, p < 0.001) had the strongest impact on the entrepreneurial intention of Vietnamese students, followed by perceived effectiveness (β = 0.252, p < 0.001), perceived consistency (β = 0.242, p < 0.001), and then need for achievement (β = 0.194, p < 0.001). Perceived appropriateness (β = 0.073, p < 0.05) had the least impact on entrepreneurial intention.

SEM analysis result

(Source: Authors’ own research)

| Hypothesis | Standardized coefficients | SE | CR | P | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: ACH → EI | 0.194 | 0.041 | 4.739 | *** | Supported |

| H2: ALT → EI | 0.276 | 0.028 | 9.817 | *** | Supported |

| H3: APP → EI | 0.073 | 0.035 | 2.073 | 0.038 | Supported |

| H4: CON → EI | 0.242 | 0.041 | 5.916 | *** | Supported |

| H5: EFF → EI | 0.252 | 0.038 | 6.560 | *** | Supported |

| Model fit indices | Obtained value | Suggested value | - | ||

| χ2/df | 2.704 | <3 | - | ||

| P | 0.044 | <0.05 | - | ||

| CFI | 0.997 | >0.90 | - | ||

| NFI | 0.996 | >0.90 | - | ||

| TLI | 0.982 | >0.90 | - | ||

| RMSEA | 0.042 | <0.07 | - | ||

Notes: p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001

The two-group SEM analysis was also used to test the moderating effect of gender on the model of entrepreneurial intention by comparing the two groups (i.e., male vs. female). In this study, 232 respondents formed the male group, while the female group consisted of 713 respondents. Two models were constructed to do the comparison test. The first model assumed that all parameters were fixed to be equal across groups (fully constrained model).

The second model allowed these parameters to vary across groups (unconstrained model). Then the free model and the constraint model were compared by using the χ2 difference test. If the change in the χ2 values in the previous step was statistically significant, then in the fourth step, the difference of each path coefficient was tested.

As shown in Table 6, the χ2 difference (Δχ2 = 18.559, p = 0.002 < 0.01) is statistically significant at less than 0.01, which suggests that the groups are different at the model level. It also indicates that male students tend to be more influenced by perceived appropriateness (APP) when forming their entrepreneurial intention (βmale = 0.234) than female students (βfemale = 0.224). Similarly, the effect of perceived effectiveness on entrepreneurial intention is stronger in the male group (βMale = 0.048) than in the female group (βFemale = 0.046). Thus, hypotheses 8 and 10 are supported. However, the scores for χ2 difference are not significant for the other paths ACH-EI, ALT-EI, CON-EI, meaning that hypotheses 6, 7, and 9 are not supported.

Results of the χ2 difference test between models

(Source: Authors’ own research)

| Moderator/hypothesis | Path estimated | Δχ2 | Δdf | p | Hypothesis supported | Standardized coefficient estimate: Female | Standardized coefficient estimate: Male |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Full model | 18.559 | 5 | 0.002 | - | - | - |

| H6 | ACH→EI | 0.019 | 1 | 0.892 | No | - | - |

| H7 | ALT→EI | 1.682 | 1 | 0.195 | No | - | - |

| H8 | APP→EI | 10.398 | 1 | 0.001 | Yes | 0.224*** | 0.234*** |

| H9 | CON→EI | 0.10 | 1 | 0.919 | No | - | - |

| H10 | EFF→EI | 10.004 | 1 | 0.002 | Yes | 0.046*** | 0.048*** |

In this study, the results of the SEM analysis showed that standardized coefficients of the cultural predictors were higher than those of personality traits. Hence, it could be concluded that cultural dimensions had a stronger impact on entrepreneurial intention than the personality traits, except for entrepreneurial alertness. However, the coefficients of independent variables in the SEM analysis of the model were approximately 0.2, implying that there is not much difference in the impact of five independent variables on entrepreneurial intention. To a certain extent, this finding was supported by the research of Ismail, et al. (2012), which found that women entrepreneurs who had chosen entrepreneurship as a career were significantly influenced by cultural factors rather than personality factors. Similarly, Adekiya and Ibrahim (2016) asserted that culture positively and significantly influences the entrepreneurship intention among female students. This study’s analytical findings are also consistent with those of previous studies by McClelland (1961), Babb and Babb (1992), Çolakoğlu and Gözükara (2016), Espiritu-Olmos and Sastre-Castillo (2015), and Karabulut (2016).

The finding that entrepreneurial alertness is the most positive influential factor is interesting. This finding reflects the current economy in Vietnam, where there are many opportunities for startups, and the marketstill underdeveloped-has the potential to grow rapidly. This result is in line with the studies by Tang, et al. (2012) and Kaish and Gilad (1991). On the contrary, the need for achievement had a moderate impact on the entrepreneurial intention of Vietnamese students. In other words, young Vietnamese people were more motivated to launch startups by the opportunity to gain economic profits, rather than by the pursuit of self-actualization. This is also supported by the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) report 2017/2018 in Vietnam, which found that many young people were afraid of failure and had started their business only when they saw a distinct opportunity in the market. The findings of this study confirm that the younger generation, including students, is increasingly motivated to pursue entrepreneurship due to favorable business opportunities and the notable economic growth in Vietnam in recent years. However, when solely driven by external business opportunities, young entrepreneurs often encounter significant challenges during the actual process of starting a business. These difficulties can diminish their motivation, particularly when balancing financial constraints and overcoming obstacles. Therefore, it is essential to conduct comparative studies between younger entrepreneurs and older startup founders to examine the differences in factors influencing entrepreneurial intention and the impact these factors have on their business success.

The entrepreneurial intention of Vietnamese students can also be meaningfully explained by the cultural predictors in the ACE model. Culture, as a foundational system of values unique to a specific group or society, influences the development of particular personality traits and drives individuals to engage in behaviors that may not be prevalent in other cultures (Pinillos and Reyes, 2011). In the context of entrepreneurship, culture significantly impacts the decisions of young people to initiate new ventures, especially in collectivist societies like Vietnam (Maheshwari, 2024). Collectivist cultures emphasize shared interests and values, in contrast to the individualistic traits typically associated with entrepreneurship, such as risk-taking and the need for achievement. The findings of this study indicate that in Vietnam, cultural influences have a stronger effect on entrepreneurial intentions than personality traits. This suggests that when starting a business in Vietnam, young entrepreneurs are not solely guided by personal characteristics, but are also deeply influenced by the broader cultural environment of their region and country. Among the three dimensions, perceived effectiveness was proved to be the most influential, while perceived appropriateness had a very slight impact on entrepreneurial intention. Similar results were found in the studies of Adekiya and Ibrahim (2016), Ismail, et al. (2012), and Karayiannis (1993). Unlike the research of Adekiya and Ibrahim (2016) in Nigeria, which concluded that perceived consistency has no significant effect on entrepreneurial intention, this study yielded the opposite result. Perceived consistency ranked second among the three cultural predictors in the ACE model that affected the entrepreneurial intention of Vietnamese students. The divergence seems to arise from the fact that in Vietnam, entrepreneurship is very new and has only recently attracted attention from stakeholders in society.

Another notable finding in this study is that the need for achievement moderately influenced the entrepreneurial intention of Vietnamese students. This is clear evidence of the emergence of a new generation of young entrepreneurs in Vietnam who are more opportunity driven than achievement driven.

Regarding the role of gender in the entrepreneurial model, this study has confirmed that male students are more influenced by perceived appropriateness and perceived effectiveness than female counterparts. This result originates from the traditional male-dominated view of Vietnamese people that entrepreneurship is more suitable for men who are breadwinners while women should opt for less risky jobs such as office work. This view persists in the Vietnamese cultural orientation, which has been profoundly affected by the Confucian ideology that men are born to be more respected than women in society.

This analysis is designed to make contributions to academicians as well as practitioners, such as government agencies and potential entrepreneurs.

In this study, we combined the trait approach to entrepreneurship and contextual factors (i.e., culture) to explain the entrepreneurial intention of young people. Thus, we aim to test the simultaneous influence of these factors on entrepreneurial intention. Based on our findings, two prominent cultural dimensions were confirmed to have a moderate influence on the entrepreneurial intention of students in Vietnam, with entrepreneurial alertness as the most crucial factor. Like in other countries, to nourish entrepreneurship in Vietnam entails strengthening and promoting entrepreneurial orientation and spirit among the youth. Consequently, entrepreneurial education must be recalibrated toward encouraging young Vietnamese people to be more achievement driven than opportunity driven. This viewpoint is very important because opportunistic entrepreneurs tend not to grow their business sustainably, but prefer to reap short-term economic gains. As a result, they are not willing to scale up their business to become big corporations. They instead prefer small and profitable operations. This action of businesspeople is not beneficial for society in light of job creation or social welfare.

This study has proved that three predictors of the ACE model have a positive influence on the entrepreneurial intention of Vietnamese students. It has shown that the students’ intention for future entrepreneurship can be promoted in three ways.

Firstly, the government, schools, and families should disseminate information that encourages students to think about being an entrepreneur as an acceptable and desirable career. This communication activity is vital because entrepreneurs have long been disrespected in traditional Vietnamese culture. Consequently, most Vietnamese parents want their children to become government workers or seek secure jobs in big corporations, rather than pursue a risk-taking business career. Only recently, as Vietnam has increasingly integrated itself into the world market, has the Vietnamese viewpoint toward a career in entrepreneurship begun to change. At this critical juncture, the government should make a long-term plan with a view to innovating the education training programs from primary to university level to change the mindset of young Vietnamese people. Furthermore, government policies should be redesigned to boost up entrepreneurship and promote social recognition of and respect for successful entrepreneurs as role models in society.

Secondly, to promote entrepreneurship, instructors at schools should make students believe that engagement in entrepreneurial activities can lead to success. Once the students are confident about such a belief, they will be more likely to develop their intention for entrepreneurial activities. Therefore, central and local governments, schools, universities, and civil society organizations should cooperate to initiate and implement regular national orientation programs that stimulate engagement in entrepreneurship. Orientation activities may vary depending on the situation of each location, but they should involve as many stakeholders in society as possible. These kinds of programs should be carried out through a combination of communication mix tools, such as social networks and mass media.

Thirdly, perceived effectiveness can be enhanced through various communication channels to make students understand that they will be capable of achieving their life-long goals with a career in entrepreneurship. Messages about the importance of entrepreneurship in society as a means of economic growth, poverty alleviation, and social welfare should be conveyed in television news, websites, campaigns, etc. Once students understand that an entrepreneurial career can lead to great success and a prestigious social position, they will be highly motivated to become entrepreneurs.

This study has some limitations. First of all, the sample is distributed mainly to business students. Thus, the research findings might be biased. Secondly, the snowball and convenient sampling methods might affect the distribution of the sample, so that there are notably more females than males in this study.

In conclusion, this study provides evidence for the positive impacts of personality traits and cultural dimensions on the entrepreneurial intention of Vietnamese students. In addition, in the context of the transition economy of Vietnam, this research has produced notable and meaningful findings. Nevertheless, further studies are necessary to explain the confounding effect of contextual, personal, and demographic factors on entrepreneurial intention in a transition economy. The scope of future research should also be broadened to include cross-country studies on this subject.