Disturbances caused by natural disasters such as forest fires, droughts and hurricanes contribute to the degradation of forest ecosystems (Jöhnsson et al. 2007; Fronczak et al. 2020; Pietsch et al. 2023) and to changes in forest ecological processes (Cantrell et al. 2014; Lodge et al. 2014; Lugo 2008). Studies by Rutledge et al. (2021) and Samec et al. (2022) indicate that the most severe damage to forest soils is mainly caused by land use changes after deforestation and extreme weather events. According to Patacca et al. (2023), wind has been responsible for most of the damage caused to European forests over the last 70 years. Observations in Europe show that climate change has increased the damage in recent decades, especially from fires and hurricanes (Seidl et al. 2011). Strong hurricane winds and storms are among the most important destructive factors in forest ecosystems and lead to significant economic losses (Blennow et al. 2010; Blennow 2012).

Several researchers, including Filipek (2008), Gardnier et al. (2013), Hotta et al. (2020), Dmyterko and Bruchwald (2020) and Morimoto et al. (2021), have studied forest damage caused by strong winds. According to the literature, hurricanes not only cause economic losses in forests, but also environmental damage. Research (Dahl et al. 2014) shows that severe cyclones can significantly alter the biogeochemical carbon cycle at the local scale. One of the most important impacts is the loss of carbon and nutrients stored in wood and soil. According to FAO: Food Agriculture Organization (2020), global carbon resources in forests amount to 662 Gt., most of which is stored in soil organic matter (SOM; 45%) and living biomass (44%), while dead wood and litter contain only 4% and 6% of carbon, respectively. Strong winds transfer large amounts of organic matter from damaged trees to the soil, especially from trees of greater height and age (Bradford et al. 2012; Suzuki et al. 2019). Reduction of living biomass in a forest ecosystem weakens photosynthesis and carbon sequestration and can enhance heterotrophic respiration, increasing the decomposition of coarse woody debris litter and soil organic carbon (SOC) (Gardnier et al. 2013). After an initial period of intensive input of dead organic matter, litter production decreases significantly and the recovery of SOC depends on the biomass of pioneer vegetation (Morehouse et al. 2008). Management of forest areas after hurricanes can affect the soil condition, although there is little research on this topic (Pietrzykowski et al. 2025).

The aim of the study was to show the effects of different methods of soil preparation for planting forests in post-hurricane areas on the levels of organic carbon and nutrients needed to rebuild the forest ecosystem.

The hypothesis of the work was that the method of soil preparation, including the agrotechnical treatments applied to forest areas after a hurricane, can limit the negative effects of this event and promote the accumulation of organic carbon and nutrients in the soil, which are necessary for the reconstruction of the forest habitat.

The study was carried out as part of the project ‘Development of principles of forest management during major natural disasters’ in the areas of the Regional Directorate of State Forests (RDLP) in Toruń, that is, Drzewianowo Forest Area, unit 198 – hours – 00: GPS (Global Positioning System) – 53.280343 17.665605; Drzewianowo Forest area, unit 198 – b: GPS – 53.281753 17.664956 and Wąwelno Forest area, unit 173 – b: GPS – 53.351687 17.686318. The study area is located in the Runowo Forest area in the Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship, which was hit by a hurricane on 11 August 2017 and was described as the ‘disaster of the century’.

The hurricane’s winds destroyed around 80,000 ha of forest stretching from Lower Silesia through Greater Poland, Kujawsko-Pomorskie and Pomerania to the Baltic coast. The first damage assessment in the Runowo Forest District estimated the loss of 660,000 m3 of wood (State Forests 2023).

The landscape in the Runowo Forest District is dominated by ground moraines, moraine hills and ribbon lakes aligned with moraines. The soils in the study area belonged to Podzols and Arenosols. The dominant forest habitats are fertile forest sites (85%) with some coniferous sites (15%). The forest stand composition includes Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris), pedunculate and sessile oak (Quercus robur L., Quercus petraea L.), silver birch (Betula pendula L.), black alder (Alnus glutinosa L.) and European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.). The selected physicochemical properties of the analysed soils are presented in Table 1.

Selected physicochemical properties of the soil of forest areas

| Site | Layer (cm) | Soil fractions (%) | pH value and acidification parameters cmol(+) kg−1 | Corg (g·kg−1) | Ntot (g·kg−1) | C:N | Organic matter content (g·kg−1) | Salinity index Na/K | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sand | Dust | Loam | pHCaCl2 | Hh | Hw | |||||||

| 1 | M | 62.61±2.42 | 35.18±2.16 | 2.20±0.75 | 3.83±0.17 | 6.22±0.90 | 1.96±0.40 | 15.87±0.60 | 0.92±0.03 | 17.32±0.72 | 17.59 | 0.256 |

| 2 | M | 62.15±3.35 | 34.00±2.90 | 3.85±0.63 | 4.06±0.09 | 3.87±0.70 | 1.57±0.44 | 4.16±0.20 | 0.26±0.01 | 15.80±1.56 | 7.17 | 0.238 |

| 3 | M | 64.52±2.62 | 32.00±2.65 | 3.48±0.88 | 4.00±0.10 | 5.41±1.29 | 1.69±0.31 | 11.36±0.90 | 0.70±0.05 | 15.95±0.89 | 19.58 | 0.423 |

| 4 | O | - | - | - | 5.12±0.15 | 4.76±1.66 | 1.15±0.76 | 292.08±8.60 | 0.77±0.05 | 25.77±2.37 | 503.54 | - |

| M | 70.23±1.94 | 27.23±2.50 | 2.31±0.44 | 4.50±0.50 | 8.98±1.10 | 1.15±0.69 | 67.94±12.01 | 2.89±0.45 | 17.33±4.59 | 117.13 | 0.044 | |

| 5 | O | - | - | - | 4.59±0.16 | 9.05±4.07 | 2.86±0.91 | 231.59±11.0 | 1.34±0.10 | 22.95±2.65 | 399.26 | - |

| M | 65.52±2.08 | 32.23±2.65 | 2.25±0.45 | 3.94±0.37 | 13.17±9.41 | 2.44±1.19 | 62.76±9.82 | 3.07±0.40 | 16.40±3.68 | 5.29 | 0.086 | |

M – mineral soil layer (0–40 cm), O – organic layer; sites: 1 – prepared area (ploughing + planting trees in the furrow); 2 – prepared area (ploughing – furrow + planting); 3 – unworked area (direct sowing + planting + sward); 4 – unworked area (no tillage + natural tree regeneration); 5 – control site – forest.

The research area is located in the third climatic zone of Poland, with an average daily temperature of 8.9°C and an annual precipitation level of 548.8 mm (average from 1991 to 2020) (IMGW 2021).

The forest areas in the post-hurricane area (RDLP Toruń) were managed in 2022. For this purpose, the soil was subjected to tillage (ploughing) before planting Quercus robur (L.) seedlings or direct seeding was carried out. Experimental objects were determined, which were as follows:

- –

site 1: prepared area (ploughing + planting trees in the furrow). Sampling point-mound in front of the furrow;

- –

site 2: prepared area (ploughing – furrow + planting). Sampling point – in the centre of the furrow. Sward at the bottom of the furrow;

- –

site 3: unworked area (direct sowing + planting + sward). Sampling point-uncultivated soil after removal of the crop;

- –

site 4: unworked area (no tillage + natural tree regeneration). Sampling site – approx. 1-m-wide strips created after the removal of self-seeding trees (corridor thinning) in the regeneration from self-seeding after the removal of trees felled by 2017 hurricane. At the time of sampling, the regeneration consisted mainly of Acer pseudoplatanus L. with a height of up to 5 m;

- –

site 5: control site – forest. The samples were collected in a stand of Quercus robur (L.) under trees that survived the hurricane. Next to this site was a plantation with sites 1, 2 and 3. The litter consisted mainly of undecomposed oak leaves.

In spring (April) 2024, a total of 88 soil samples were taken from four post-hurricane areas and one control area (forest) in the Runowo Forest District. The samples were collected in four replicates from the organic layer (O) of sites with this layer (sites 4 and 5) and from four soil layers: 0–5, 5–10, 10–20 and 20–40 cm.

The samples were dried at 40°C, sieved through a 2-mm sieve and ground in a FRISCH Pulverisette 2 agate mill (pre-treatment according to ISO 11464:2006). The samples prepared in this way were subjected to physicochemical analyses, which consisted of the following:

- –

soil fraction: by the laser diffraction method according to PN-Z-19012:2020,

- –

dry matter: by the gravimetric method according to PN-ISO 11465:1999,

- –

hydrolytic acidity (Hh): by the titration method according to PN-R-04027:1997,

- –

exchangeable acidity (Hw): in 0.1 mol BaCl2·dm−3 extracts according to PN-EN ISO 14254:2011,

- –

pH in 0.01 mol CaCl2·dm−3 solution: by the potentio-metric method according to PN-EN 1484:1999,

- –

total organic carbon (Corg) and total nitrogen (TN; Norg): by high-temperature combustion method (PNISO 10694:2002 for C and PN-ISO 13878:2002 for N),

- –

total mineral content: Ptot, Ktot, Mgtot, Catot, Natot after digestion with aqua regia (3:1 mixture of HCl and HNO3) and determination using the inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICPOES) method according to PN-EN ISO 11885:2009 and

- –

content of basic cations Ca2+, Mg2+, K+, Na+ and acidic cations H+, Al3+ in a 0.1 mol BaCl2·dm−3 in the soil solution at pH 8.1: by ICP-OES according to PN-EN ISO 11260:2011.

All analyses were performed in the accredited Laboratory of Environmental Chemistry (AB 740) of the Forest Research Institute in Sękocin Stary, Poland.

The obtained research results were statistically processed, and a one-way analysis of variance was performed for the chemical parameters in the soil of forest surfaces examined with different post-hurricane regeneration methods. Significant differences between the mean values of the analysed parameters on forest surfaces were assessed using Tukey HSD (Honest Significant Difference) test (p < 0.05). Non-parametric Spearman rank correlations were determined between the assessed physicochemical properties of forest surface soil, including: pHCaCl, Corg, Ntot, Ptot, C:N, sum of the base cations (SBC) and cation exchange capacity (CEC) at the following significance levels: p < 0.05 (*), 0.01 (**) and 0.001 (***). The statistical analysis of the research results was performed using Statistica 13.3 software (TIBCO Software Inc. 2017).

The soils of the studied forest sites of Runowo Forest District were characterised by a pH ranging from very acidic to highly acidic (pHCaCl2 3.74–4.59) (Tab. 2), with the least acidic soil observed at site No. 4 (pHCaCl2 4.50±0.51).

pH and content of total forms of mineral elements in the soil of forest areas

| Site | Layer (cm) | pHCaCl2 | Corg (g·kg−1) | Ntot (g·kg−1) | C:N | Ptot (mg·kg−1) | Ktot (mg·kg−1) | Catot (mg·kg−1) | Mgtot (mg·kg−1) | Natot (mg·kg−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0–5 | 3.74±0.25 | 13.15±0.30 | 0.75±0.02 | 17.35±0.51 | 294.2±47.0 | 580.2±62.71 | 362.7±32.01 | 626.0±17.61 | 55.4±11.34 |

| 5–10 | 3.79±0.08 | 21.62±0.48 | 1.23±0.03 | 16.95±0.52 | 318.7±38.84 | 577.0±45.85 | 506.5±111.10 | 627.7±47.23 | 56.1±11.33 | |

| 10–20 | 3.90±0.22 | 19.56±0.38 | 1.12±0.02 | 17.42±0.83 | 318.5±57.25 | 589.5±47.79 | 553.5±112.50 | 659.0±23.60 | 49.9±4.44 | |

| 20–40 | 3.88±0.09 | 9.14±0.08 | 0.52±0.01 | 17.57±1.05 | 290.0±25.49 | 577.5±24.54 | 364.3±31.05 | 672.5±53.13 | 54.8±2.86 | |

| Mean±SD | 3.83±0.17B | 15.87±0.60B | 0.92±0.03AB | 17.32±0.72A | 305.4±1.46A | 581.0±42.58B | 446.7±97.54B | 646.3±40.15B | 54.1±7.95A | |

| 2 | 0–5 | 4.03±0.13 | 6.66±0.12 | 0.41±0.01 | 16.02±0.56 | 279.5±17.97 | 592.2±35.26 | 331.7±23.51 | 676.5±37.83 | 54.6±2.30 |

| 5–10 | 4.06±0.10 | 4.73±0.09 | 0.29±0.01 | 16.32±1.03 | 285.7±25.38 | 638.0±81.47 | 324.73±31.92 | 728.0±97.00 | 59.4±10.5 | |

| 10–20 | 4.08±0.09 | 3.54±0.03 | 0.22±0.01 | 15.77±0.31 | 289.2±36.08 | 680.5±96.30 | 362.0±34.88 | 767.2±59.20 | 60.5±7.12 | |

| 20–40 | 4.05±0.10 | 1.71±0.05 | 0.11±0.01 | 15.10±3.11 | 303.2±72.33 | 790.2±87.22 | 373.2±24.10 | 878.2±47.28 | 73.6±7.16 | |

| Mean±SD | 4.06±0.10B | 4.16±0.20B | 0.26±0.01B | 15.81±1.56A | 289.4±39.76A | 675.2±88.81B | 347.9±26.76B | 762.5±65.33B | 62.0±9.83A | |

| 3 | 0–5 | 3.98±0.12 | 21.84±0.91 | 1.33±0.01 | 16.37±0.87 | 332.0±20.9 | 620.5±19.74 | 521.7±20.06 | 607.2±35.48 | 60.6±8.86 |

| 5–10 | 3.96±0.08 | 14.34±0.42 | 0.86±0.03 | 16.67±0.71 | 316.2±24.33 | 568.0±6.48 | 402.5±20.54 | 614.5±34.18 | 56.3±5.16 | |

| 10–20 | 3.99±0.12 | 6.04±0.12 | 0.38±0.01 | 15.87±0.22 | 309.2±48.63 | 614.5±9.75 | 325.7±20.16 | 668.0±36.23 | 56.8±4.67 | |

| 20–40 | 4.08±0.05 | 3.20±0.03 | 0.20±0.01 | 14.90±0.51 | 290.5±46.89 | 704.0±22.68 | 391.5±24.61 | 699.2±42.31 | 62.1±1.70 | |

| Mean±SD | 4.00±0.10B | 11.36±0.8B | 0.70±0.04AB | 15.96±0.89A | 312.0±36.81A | 626.7±56.77B | 410.4±20.23B | 647.2±36.55B | 58.9±6.61A | |

| O | 5.12±0.15 | 292.08±8.60 | 11.34±0.34 | 25.77±2.37 | 951.2±87.51 | 1639.2±441.60 | 16,077.2±49.67 | 1533.7±31.76 | 53.6±7.59 | |

| 4 | 0–5 | 4.68±0.50 | 19.71±0.63 | 1.27±0.03 | 15.32±1.00 | 221.0±10.30 | 982.2±307.98 | 1142.7±71.28 | 896.7±45.64 | 51.4±3.27 |

| 5–10 | 4.16±0.40 | 14.10±0.40 | 0.92±0.02 | 15.22±1.00 | 190.5±27.50 | 966.5±292.61 | 814.5±72.35 | 901.7±34.41 | 53.3±5.57 | |

| 10–20 | 4.16±0.41 | 9.00±0.23 | 0.58±0.02 | 15.50±1.73 | 168.2±39.93 | 985.5±337.85 | 688.5±43.56 | 934.0±31.45 | 53.4±2.14 | |

| 20–40 | 4.42±0.36 | 4.82±0.09 | 0.32±0.03 | 14.82±1.89 | 138.5±29.85 | 907.5±444.80 | 681.5±43.40 | 929.7±38.28 | 58.4±9.56 | |

| Mean±SD | 4.50±0.51A | 67.94±12.0A | 2.89±0.45AB | 17.33±4.59A | 333.9±46.25A | 1096.2±410.4A | 3880.9±68.21A | 1039.0±35.87A | 54.0±6.05A | |

| O | 4.59±0.16 | 231.59±11.0 | 10.05±0.42 | 22.92±2.65 | 720.5±46.52 | 1379.0±195.08 | 6298.7±301.50 | 1274.5±23.50 | 44.9±9.73 | |

| 5 | 0–5 | 3.84±0.23 | 46.88±0.75 | 2.97±0.04 | 15.77±0.77 | 335.5±38.21 | 1108.7±337.08 | 972.5±25.67 | 918.5±28.81 | 62.7±11.7 |

| 5–10 | 3.61±0.08 | 19.54±0.37 | 1.28±0.02 | 15.27±0.77 | 234.7±37.02 | 989.7±287.77 | 442.7±25.47 | 951.2±25.53 | 50.2±3.11 | |

| 10–20 | 3.75±0.08 | 10.83±0.10 | 0.74±0.10 | 14.65±0.72 | 204.2±16.21 | 1047.7±371.38 | 447.7±64.04 | 1042.7±30.52 | 61.6±17.21 | |

| 20–40 | 3.90±0.10 | 4.94±0.05 | 0.37±0.06 | 13.92±1.34 | 202.0±10.10 | 1326.0±601.92 | 526.2±56.74 | 1297.7±34.52 | 62.3±11.25 | |

| Mean±SD | 3.94±0.40B | 62.76±9.8A | 3.07±0.40A | 16.40±3.68A | 339.4±42.45A | 1170.2±366.8A | 1737.6±48.56A | 1096.9±34.24A | 56.3±12.74A |

B – significant differences between the average values of the studied parameters; sites: 1 – prepared area (ploughing + planting trees in the furrow); 2 – prepared area (ploughing – furrow + planting); 3 – unworked area (direct sowing + planting + sward); 4 – unworked area (no tillage + natural tree regeneration); 5 – control site – forest.

The total organic carbon (Corg) content in the studied forest soils varied and depended on soil depth. The highest content of this component was found in the organic layer (litter) at site 4 (292.08 g·kg−1), which had no agrotechnical treatments and contained self-seeded trees, and at the control site 5, which was a forest (site 5) (231.59 g·kg−1). In the mineral soils of the remaining three sites (1, 2, 3), the Corg content was low (1.71–21.84 g·kg−1). The lowest Corg content was found at site 2, a cultivated site where tree seedlings had been planted in furrows (Tab. 2, Fig. 1).

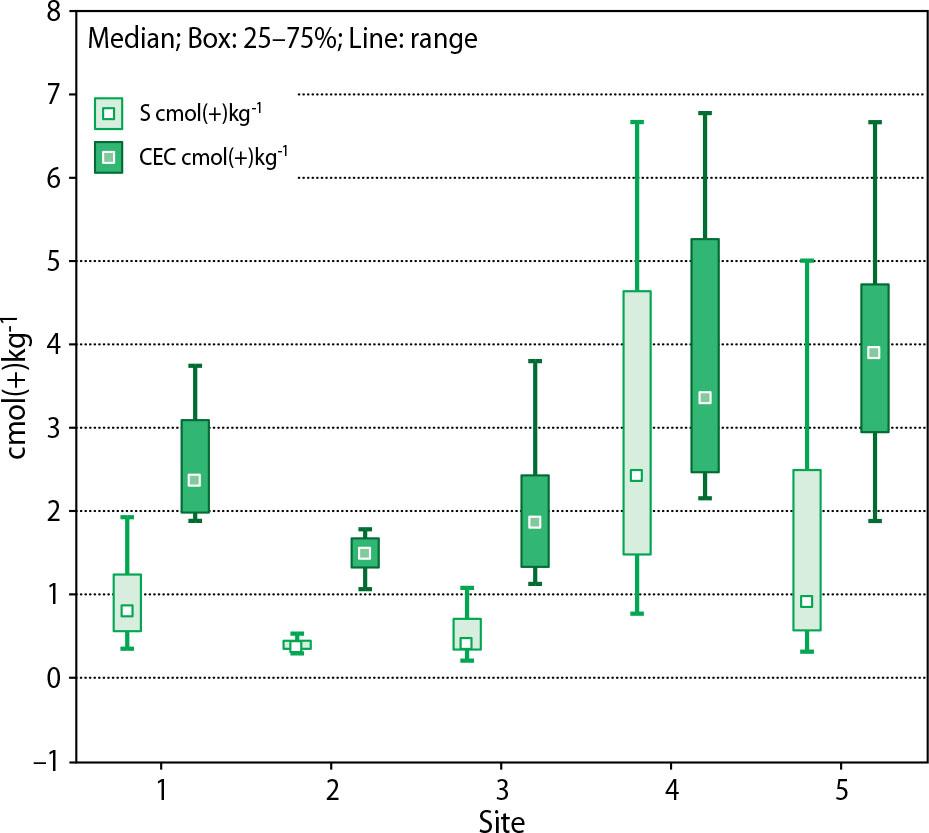

The sum of base cations (SBC) and cation exchange capacity (CEC) in soil (O, 0–40 cm depth) as a function of different land management practices of forest areas after the 2017 hurricane disaster

Sites: 1 – prepared area (ploughing + planting trees in the furrow); 2 – prepared area (ploughing – furrow + planting); 3 – unworked area (direct sowing + planting + sward); 4: unworked area (no tillage + natural tree regeneration); 5 – control site – forest.

A one-way ANOVA revealed that the mean Corg content was significantly higher at the sites where no agrotechnical treatments were applied, that is, 4 (‘self-seeding’) and 5 (forest), compared to the sites where the soil was prepared before planting the seedlings (sites 1, 2) and the sites where the seedlings were planted in un-prepared soil (site 3).

The TN content was highest in the organic layer of sites 4 and 5 (10.05–11.34 g Ntot·kg−1), while in the mineral layer it was significantly lower (0.11–2.97 g Ntot·kg−1). As the sampling depth increased, the nitrogen content decreased due to the horizontal allocation of organic matter in the soil profile. The soil richest in Ntot was found at the sites left undisturbed, that is, the site with self-seeded trees (site 4: 2.89 g Ntot·kg−1) and the site under the forest (site 5: 3.07 g Ntot·kg−1), while the remaining sites had very low Ntot content (0.26–0.92 g Ntot·kg−1). The lowest nitrogen content was recorded in the furrows (site 2: 0.26 g Ntot·kg−1).

The C:N ratio in the analysed forest areas ranged from 13.92 to 25.77 and was highest in the organic layer of sites 4 and 5, which were free from agrotechnical treatments (i.e. self-seeded trees: 25.77 and the control site: 22.92). In the mineral soil layers subjected to agro-technical treatments (sites 1 and 2), the ratio was lower ranging from 13.92 to 17.57. Significant differences were found in the average organic carbon content of the soils at the examined sites (Tab. 2).

The average total phosphorus content in the mineral layers of the analysed soils was lower than in cultivated soils (70.0–2660.0 mg·kg−1 acc. gios.gov.pl.), regardless of the site, and ranged from 186.2 to 335.5 mg Ptot·kg−1, while in the organic layer it was significantly higher, ranging from 720.5 to 951.2 mg Ptot·kg−1. In this case, the highest total phosphorus content was found in the soil of the control site (5) and the self-seeded trees site (4). The total phosphorus content was significantly lower in the mineral soil of sites subjected to agrotechnical treatments before cultivation (sites 1, 2) and in the site where seedlings were planted in unprepared soil (site 3).

The total potassium content in the soils of the examined forest sites varied from 568.0 to 1108.7 mg Ktot·kg−1 in mineral layers and from 1379.0 to 1639.2 mg Ktot·kg−1 in the organic layer (Tab. 2). The average potassium content was significantly higher at sites 4 and 5, which contained an organic layer, compared to soils composed only of mineral layers (sites 1, 2, 3).

The total calcium content in the soils of the forest sites varied depending on the site and soil layer. In mineral layers, it ranged from 324.7 to 1142.7 mg Catot·kg−1, while in the organic layer it was several times higher (6298.7–16,077.2 mg Catot·kg−1). In addition, the Catot content was significantly higher in the soil of site 4 (self-seeded trees) and site 5 (forest) than in the other forest sites (Tab. 2).

The total magnesium content in the forest soils ranged from 607.2 to 1297.7 mg Mgtot·kg−1 in the mineral layers, while in the organic layer it was nearly twice as high (1274.5–1533.7 mg Mgtot·kg−1). Similar to other nutrients, the highest magnesium content was found in the litter layer of site 4 (self-seeded trees) and the control site (5). In addition, it was observed that in the mineral soil layers, the magnesium content increased with depth, suggesting that this element is leached deeper into the soil.

SBC (Na+, K+, Mg2+, Ca2+) in the mineral soil layers of the investigated forest sites ranged from 0.383 to 4.838 cmol(+) SBC·kg−1, while it was significantly higher in the organic layer at 24.73 to 35.21 cmol(+) SBC·kg−1. The base of cation saturation of the mineral soil layers was highest in the surface layer (0–5 cm) and decreased with depth (Tab. 3, Fig. 1). It was found that the soil at site 4, where self-sown trees were located and no agrotechnical treatments were applied, had the highest average base cation content (9.406 cmol(+)SBC·kg−1) and differed from the other sites with agrotechnical treatments (sites 1, 2, 3), with the exception of the control site (5). The lowest average base cation content was found in the soil where the tree seedlings were planted in furrows (0.433 cmol(+) SBC·kg−1).

Contents of exchangeable cations in the soil of forest areas

| Site | Layer (cm) | Na+ (cmol(+)·kg−1) | K+ (cmol(+)·kg−1) | Mg2+ (cmol(+)·kg−1) | Ca2+ (cmol(+)·kg−1) | Al3+ (cmol(+)·kg−1) | SBC (cmol(+)·kg−1) | CEC (cmol(+)·kg−1) | BS (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0–5 | 0.028±0.01 | 0.134±0.04 | 0.074±0.02 | 0.361±0.12 | 1.212±0.09 | 0.597±0.16 | 2.08±0.22 | 28.48±6.02 |

| 5–10 | 0.038±0.01 | 0.136±0.05 | 0.188±0.05 | 1.052±0.32 | 1.265±0.16 | 1.414±0.34 | 3.07±0.49 | 45.79±7.55 | |

| 10–20 | 0.036±0.01 | 0.144±0.09 | 0.215±0.09 | 1.106±0.46 | 1.185±0.36 | 1.502±0.63 | 3.09±0.40 | 47.96±14.43 | |

| 20–40 | 0.040±0.01 | 0.094±0.094 | 0.071±0.03 | 0.330±0.11 | 1.329±0.21 | 0.535±0.18 | 2.05±0.16 | 25.89±7.08 | |

| Mean±SD | 0.036±0.01A | 0.127±0.06A | 0.137±0.08B | 0.713±0.46B | 1.247±0.21A | 1.012±0.57B | 2.57±0.36B | 37.03±10.23B | |

| 2 | 0–5 | 0.023±0.01 | 0.113±0.02 | 0.068±0.02 | 0.262±0.31 | 1.074±0.17 | 0.467±0.05 | 1.67±0.11 | 28.12±4.08 |

| 5–10 | 0.023±0.01 | 0.089±0.01 | 0.056±0.02 | 0.285±0.20 | 1.074±0.18 | 0.454±0.23 | 1.58±0.25 | 28.11±11.02 | |

| 10–20 | 0.034±0.01 | 0.073±0.01 | 0.044±0.02 | 0.262±0.16 | 1.018±0.11 | 0.413±0.18 | 1.47±0.16 | 27.64±9.23 | |

| 20–40 | 0.061±0.03 | 0.070±0.01 | 0.046±0.01 | 0.216±0.04 | 0.881±0.22 | 0.395±0.04 | 1.35±0.26 | 29.95±5.20 | |

| Mean±SD | 0.036±0.02A | 0.087±0.06B | 0.054±0.02B | 0.256±0.12B | 1.00±0.17B | 0.433±0.14B | 1.52±0.22B | 28.46±7.19B | |

| 3 | 0–5 | 0.039±0.01 | 0.180±0.05 | 0.211±0.01 | 1.471±1.02 | 0.987±0.28 | 1.901±1.16 | 3.15±0.84 | 56.04±22.43 |

| 5–10 | 0.030±0.01 | 0.116±0.04 | 0.116±0.07 | 0.841±0.50 | 1.140±0.22 | 1.103±0.61 | 2.53±0.46 | 41.35±17.82 | |

| 10–20 | 0.028±0.01 | 0.073±0.01 | 0.039±0.01 | 0.243±0.08 | 1.230±0.59 | 0.383±0.12 | 1.70±0.24 | 22.11±4.31 | |

| 20–40 | 0.031±0.01 | 0.063±0.02 | 0.033±0.01 | 0.165±0.04 | 0.926±0.05 | 0.383±0.12 | 1.88±1.27 | 21.87±4.53 | |

| Mean±SD | 0.032±0.01A | 0.108±0.05B | 0.100±0.02B | 0.680±0.74B | 1.070±0.20B | 0.944±0.88B | 2.32±0.48B | 35.34±16.77B | |

| O | 0.103±0.02 | 1.901±0.04 | 5.702±0.67 | 27.506±0.86 | 0.027±0.01 | 35.21±1.65 | 36.22±2.08 | 97.25±1.13 | |

| 4 | 0–5 | 0.021±0.01 | 0.282±0.09 | 0.727±0.02 | 3.802±1.36 | 0.369±0.28 | 4.839±1.63 | 5.32±1.57 | 90.15±6.41 |

| 5–10 | 0.021±0.01 | 0.172±0.01 | 0.351±0.03 | 2.356±1.45 | 0.934±0.51 | 2.900±1.60 | 4.15±1.19 | 67.32±6.02 | |

| 10–20 | 0.028±0.01 | 0.109±0.02 | 0.249±0.02 | 1.673±1.41 | 1.007±0.59 | 2.059±1.60 | 3.3301.32 | 67.51±8.02 | |

| 20–40 | 0.035±0.02 | 0.084±0.04 | 0.245±0.01 | 1.655±1.22 | 0.668±0.43 | 2.020±0.86 | 2.8101.15 | 67.14±25.41 | |

| Mean±SD | 0.043±0.03A | 0.510±0.74A | 1.455±0.03A | 7.398±1.45A | 0.700±0.53B | 9.406±1.62A | 10.37±1.44A | 75.88±22.40A | |

| O | 0.104±0.03 | 1.175±0.026 | 3.782±0.45 | 19.671±2.90 | 0.141±0.06 | 24.73±1.65 | 25.57±3.75 | 96.73±0.89 | |

| 5 | 0–5 | 0.057±0.01 | 0.360±0.05 | 0.684±0.02 | 3.006±0.76 | 1.186±0.08 | 4.107±0.86 | 6.00±0.77 | 68.01±7.55 |

| 5–10 | 0.028±0.01 | 0.143±0.02 | 0.168±0.04 | 0.510±0.13 | 2.300±0.50 | 0.805±1.60 | 3.65±0.58 | 19.64±3.80 | |

| 10–20 | 0.057±0.01 | 0.115±0.01 | 0.123±0.05 | 0.330±0.18 | 2.297±0.58 | 0.626±0.21 | 3.15±0.66 | 19.64±3.80 | |

| 20–40 | 0.037±0.01 | 0.121±0.04 | 0.210±0.02 | 0.679±0.64 | 1.916±0.60 | 1.040±0.22 | 3.13±1.42 | 28.74±14.95 | |

| Mean±SD | 0.057±0.03A | 0.382±0.43A | 0.992±0.09AB | 4.839±2.60AB | 1.574±0.92A | 6.271±0.96AB | 8.30±2.36AB | 47.28±12.40B |

B – significant differences between the average values of the studied parameters; sites: 1 – prepared area (ploughing + planting trees in the furrow); 2 – prepared area (ploughing – furrow + planting); 3 – unworked area (direct sowing + planting + sward); 4 – unworked area (no tillage + natural tree regeneration); 5 – control site – forest.

The sorption capacity of the investigated mineral soils ranged from 1.35 to 6.00 cmol(+)·kg−1, while it was significantly higher in the organic layer (25.57–36.22 cmol(+)SBC·kg−1). The highest CEC value was found in the plot without agrotechnical treatments with self-seeded trees (site 4); the average value of this parameter differed from those of the other forest sites (Tab. 3, Fig. 1) except the control site (site 5).

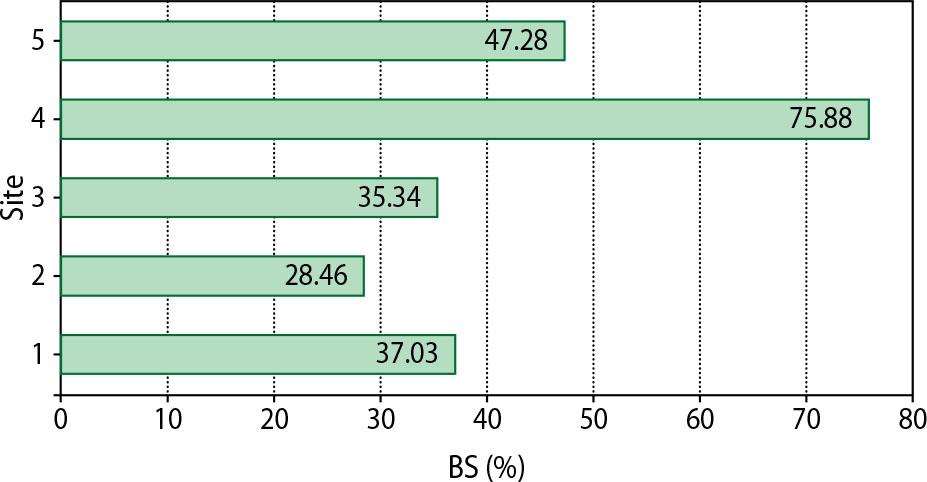

The base saturation (BS) parameter indicates the percentage of base cations in the total sorption capacity and serves as an agrotechnical indicator of the soil quality. At 75.88%, the BS value in the forest soils was highest in the area without agrotechnical treatment (site 4). The lowest BS value was found in site 2, where the tree seedlings were planted in furrows (28.46%) (Tab. 3, Fig. 2), and the BS value in the forest soils was highest in the area without agrotechnical treatment (object 4) at 75.88. The lowest BS value was found in site 2, where the tree seedlings were planted in furrows (28.46%) (Tab. 3, Fig. 2).

The degree of base saturation (BS %) of the soil (O, 0–40 cm depth) sorption complex depending on different land management methods of forest areas after the 2017 hurricane disaster

Sites: 1 – prepared area (ploughing + planting trees in the furrow); 2 – prepared area (ploughing – furrow + planting); 3 – unworked area (direct sowing + planting + sward); 4 – unworked area (no tillage + natural tree regeneration); 5 – control site – forest.

Evaluation of the non-parametric Spearman correlations between the assessed physicochemical parameters revealed that most of the correlation coefficients were positive, except for three cases: Hw × BS (r = −0.509***), Hw × SBC (r = −0.296**) and clay × Corg (r = −0.364***). The negative values of these coefficients indicate a weak influence of soil acidity on the reduction of base cations in the soil, as well as the effect of the granulo-metric fraction clay on the content of Corg. The range of positive correlation values was large, ranging from r = 0.249* to r = 0.995*** (Tab. 4). The strongest correlations were observed between the Corg content and components such as Ntot (r = 0.995***), CEC (r = 0.824***), as well as between Ntot and CEC (r = 0.853***) and SBC (r = 0.787***).

Spearman non-parametric correlations between the physicochemical parameters in forest soils (n = 88)

| Parameter | Spearman r | Level of p |

|---|---|---|

| pHCaCl2 × SBC | 0.316 | ** |

| pHCaCl2 × BS | 0.531 | *** |

| Corg × Ntot | 0.995 | *** |

| Corg × Ptot | 0.362 | ** |

| Corg × C:N | 0.408 | *** |

| Corg × SBC | 0.764 | *** |

| Corg × CEC | 0.824 | *** |

| Corg × BS | 0.591 | *** |

| Ptot × C:N | 0.501 | *** |

| Ntot × C:N | 0.408 | ** |

| Ntot × SBC | 0.787 | *** |

| Ntot × CEC | 0.853 | *** |

| Sand × C:N | 0.314 | ** |

| Sand × BS | 0.311 | ** |

| Sand × Ptot | 0.517 | *** |

| Loam × Corg | –0.364 | ** |

| Dust × Corg | 0.506 | *** |

| Dust × Ntot | 0.523 | *** |

| Dust × SBC | 0.449 | *** |

| Dust × CEC | 0.621 | *** |

| Dust × BS | 0.249 | * |

| Hw × SBC | –0.296 | ** |

| Hw × BS | –0.509 | *** |

– p < 0.05;

– 0.01;

– 0.001;

BS – the basa saturation; CEC – cation change capacity; SBC – the cation change capacity.

This study hypothesised that the method of managing post-hurricane forest areas can mitigate the environmental effects of soil degradation by improving the SOM content and nutrient availability essential for forest vegetation. The foundation of ecosystem functioning is carbon metabolism, and the processes of organic matter decomposition and its mineralisation into CO2 drive the carbon cycle and sequestration in the soil (Pan et al. 2011).

The study results indicate that the content of Corg, total nutrient forms and saturation of the soil sorption complex in the studied forest areas varied and depended on the soil preparation method for new forest plantings. The average Corg content was significantly higher in areas without agrotechnical treatments, 4 (‘natural regeneration’) and 5 (forest) (67.94–62.76 g Corg·kg−1), compared to areas subjected to preliminary soil preparation (objects: 1, 2, 3) (4.16–15.85 g Corg·kg−1). However, the highest carbon content was found in the organic layer of sites 4 and 5 (292.08 and 231.59 g Corg·kg−1, respectively). A similar trend was observed for Ntot content. The soil in areas left undisturbed, with ‘natural regeneration’ of trees (object 4: 2.89 g Ntot·kg−1) and under the forest (site 5: 3.07 g Ntot·kg−1), contained much higher nitrogen levels compared to other objects (0.26–0.92 g Ntot·kg−1).

It is estimated that TN content in the top layer of forest soils is high (5.0–25.0 g Ntot·kg−1) and decreases to 0.20 g Ntot·kg−1 with depth (Mroczkowski and Stuczyński 2024). The vertical distribution of Corg and Ntot in the soil profile results from the fact that both components enter the soil through plant litterfall and undergo further transformation processes (Błońska and Januszek 2010; Dziadowiec et al. 2007). According to the European Soil Bureau criteria, a Corg content below 10.0 g·kg−1 (<17.2 g·kg−1 SOM) indicates very low soil fertility, while a value of Corg >60.0 g·kg−1 (>102.0 g·kg−1 SOM) indicates high fertility (Kuś 2015).

The study shows that parameters such as SBC, CEC and BS were significantly higher in undisturbed areas (sites 4 and 5), whereas the lowest values were recorded in soils where tree seedlings were planted in furrows (site 2). Based on the sum of base cations in the soil, the habitat conditions of the studied areas can be assessed. Low base cation content (<5.0 cmol(+)SBC·kg−1) indicates poor (dystrophic) sites, 5–15 cmol(+)SBC·kg−1 represents mesotrophic sites, and high base content (>15.0 cmol(+)SBC·kg−1) corresponds to nutrient-rich (eutrophic) sites. In addition, a low BS value (<50%) may indicate a risk of soil degradation, whereas a high BS value (>70%) suggests good soil condition (Kaźmierowski 2012). The highest BS value was recorded in site 4, that is, without agro-technical treatments (75.88%), while the lowest was in site 2, where tree seedlings were planted in furrows (28.46%).

Positive non-parametric Spearman rank correlations were also found between Corg and components such as Ntot (r = 0.995***), CEC (r = 0.824***), as well as between Ntot and CEC (r = 0.853***) and SBC (r = 0.787***). Weak positive correlations were obtained between pH and SBC (r = 0.316**) and BS (r = 0.531***). According to Ross et al. (2008) and Gustafsson et al. (2018), nutrient availability in soil depends on soil acidity, concentrations of Al3+ and H+ and base cations such as Ca2+, Mg2+, Na+ and K+.

Studies by some authors (Bartuška et al. 2015; Jimênez-González et al. 2016) suggest that the accumulation of SOC plays a key role in soil regeneration after ecosystem disturbances. SOM regulates many important physical, chemical and biological soil properties (Bodlák et al. 2012; Pietrzykowski et al. 2025). According to Brady and Weil (2017), higher organic carbon content may indicate increased total base cations (SBC), CEC and TN. Rasmussen et al. (2018) and Rowley et al. (2020) demonstrated that certain cations, such as Ca2+ and Al3+, can stabilise SOC reserves by binding organic compounds to mineral surfaces. This may reduce the leaching of labile carbon fractions (DOC: Dissolved Organic Carbon) and nutrients into deeper soil layers (Błońska et al. 2018; Burzyńska 2013; Burzyńska and Sztabkowski 2023).

Literature contains limited studies on carbon flux changes in disturbed ecosystems depending on their regeneration method (Pietrzykowski et al. 2025). According to Williams et al. (2016), the method of regenerating a damaged forest ecosystem significantly affects the carbon cycle. Research indicates that carbon and nutrient accumulation in the upper soil layers is greater in forest soils undergoing natural regeneration with abundant self-seeding (Acer pseudoplatanus L.) than in mechanically prepared soils or soils without preparation but lacking tree self-seeding. Similar trends were observed by Dahl et al. (2014) and Baldwin et al. (2001). The method of soil preparation for new forest plantations on post-hurricane areas influenced the accumulation of organic carbon and soil nutrient content.

Literature contains limited studies on carbon flux changes in disturbed ecosystems depending on their regeneration method (Pietrzykowski et al. 2025). According to Williams et al. (2016), the method of regenerating a damaged forest ecosystem significantly affects the carbon cycle.

The Corg content in forest soils was high in the organic layer of the plots without agrotechnical treatment (4) and the control plot (5). Low values were found in the mineral layers, especially in site 2, where tree seedlings were planted in furrows.

Soil nutrient content including total forms of Ntot, Ptot, Ktot, Mgtot as well as total base cations (SBC) and CEC was high in the organic layer of the undisturbed plot with natural regeneration of deciduous tree species (4) and the control plot (5). The lowest nutrient content was found in the mineral soil.

Different methods of site preparation for forest plantations on post-hurricane sites showed different susceptibility to soil regeneration (from most to least susceptible): (5- control – forest) = (4- unworked area: no tillage + natural tree regeneration) < (3- unworked area: direct sowing + planting + sward) < (1- prepared area: ploughing + planting trees in the furrow) < (2- prepared area: ploughing – furrow + planting).