Beech is a deciduous tree, a genus with nine species and one hybrid, in the family Fagaceae, native to three continents: Europe, Asia, and North America (Grimshaw 2021). The studies carried out in the 1930s, based only on the observation of the morphological characteristics of the beech species, gave rise to various controversies, as there was a great variety of these characteristics.

In Europe, the genus Fagus is well represented, occupying extensive compact areas in hilly and mountainous regions. It is also present in small areas, outside its compact range, where it forms the so-called “beech islands”.

Fagus sylvatica is one of the most common hardwood trees in north-central Europe; in France, it constitutes alone about 15% of all non-conifers. Eastern Europe is also home to the lesser-known oriental beech (Fagus orientalis) and Crimean beech (Fagus taurica) (Shen 1992; Grinţzescu 1927). Clinovschi considered that the genus is represented by only two species, F. sylvatica and F. orientalis, both of which have high genetic and ecological plasticity, and F. taurica is only a hybrid between F. orientalis and F. sylvatica (Clinovschi 2005). The ecological plasticity of the beech allowed, on the one hand, the presence in the range of individuals of F. sylvatica in areas with pedo-climatic conditions much different from the ecological optimum of this species; on the other hand, the expansion of the area of the species F. orientalis, which is an eastern species, has migrated to the western areas. Beech individuals would be able to adjust physiological and morphological responses to climate change conditions; for this reason, phenotypic plasticity is discussed in phenological models (Kramer et al. 2017). Molecular marker studies revealed that the differentiation of F. orientalis and F. sylvatica as separate species is a relatively (Kandemir and Zeki 2009). F. sylvatica is a European species; it is widespread in the west, center, and south of the continent. It is present from the Atlantic to the North of Moldova; from the Pyrenees to the Mediterranean Coast, including Greece, up to the south of Scotland and Scandinavia. In north-western Europe, it becomes a tree of plains and hills, and in the south, it appears at over 1500 m (Alps – 1650 m, Pyrenees – 2000 m, and Etna – 2160 m) (Clinovschi 2005). It has a great capacity for acclimatization, forming “geographic races” (F. sylvatica var. britannica (Great Britain), F. s. scandinavica (southern Scandinavia), F. s. borealis (the coast of the Baltic Sea), F. s. celtica (northern France), and F. s. pomeranica (Denmark)); and climate types (F. s. pyrenaica (Pyrenees), F. s. gallica (Jura), F. s. alpina (Western Alps), F. s. austriaca (Austrian Alps), F. s. apennina (Apennines), F. s. hercynica (Central Europe – mountain area and hillbilly), F. s. carpathica (Slovakian Carpathians), F. s. silesiaca (Poland), F. s. polonica (Poland), F. s. transsilvanica (Romanian Carpathians), F. s. balcanica (Balkans), and F. s. podolica (Podolic Plateau, Central Moldavian). Today, European beech (F. sylvatica L.) seems to be a markedly successful tree species in the north-east of its distribution range. Numerous attempts consistently have failed to locate a distinct distribution edge for European beech (Bolte et al. 2007). The beech ecological requirements in central Europe are the following: at an average annual temperature of 10°C, the annual precipitation necessary is in the range of 900–1000 mm. For example, in England at 5–6°C, the beech needs 500 mm of precipitation. It is a species that is sensitive to drought, scorching heat, and dryness; low rainfall can be compensated by the higher atmospheric humidity, so that, in the hills, the beech appears in the valleys and the lower third of the slopes (Clinovschi 2005). It is sensitive to late frosts and early frosts, as well as excessive frosts, the latter causing it to “jellify”. Also, it is a shade species (the third, after yew and fir); beech forests, by the crowning, achieve a strong shading, which is why shrubs are missing and the herbaceous carpet is poor (Clinovschi 2005). The beech species shows high potential and high productivity in registering on eu-meso-basic brown soils with a high humus content, which is rich, ventilated, regenerated, and permeable, regardless of the substrate. They form pure stands also on poorer, more acidic, but loose soils, which are permeable, sufficiently moist, airy, and textured, such as the ones on crystalline shales, granites, sandstones, and conglomerates. They do not like soils that are too wet, clayey, pseudo-glazed, with stagnant water, as well as dry, alluvial, and peatlands (Clinovschi 2005). Being a cosmopolitan species, the compensation of environmental factors appears in the type of substrate with climatic conditions (temperature) (Clinovschi 2005). However, it is difficult to correlate European beech distribution margins with single macro-climatic factors. Moreover, the adaptation of European beech populations and provenances to drought and frost varies. The phenotypic plasticity and evolutionary adaptability of European beech appear to be underestimated. These characteristics may counteract a further contraction of the European beech range arising from climate change in the future (Bolte et al. 2007). The European beech has a very high ecological plasticity, growing on lands with varied altitudes, starting from 5 m in Denmark and reaching 1150 m in Bulgaria (Mohytych et al. 2024). The forests of European beech present in the extra area, which form the so-called islands, represent glacial relicts. The spread in F. sylvatica from its glacial refugia started during the late-glacial period and was continuous and irreversible until the present, without important retreats and readvances, so that the modern distribution of beech in central and northern Europe corresponds to its maximum post-glacial extension (Magri 2008).

Fagus orientalis is indigenous to the Balkans in the west, through Anatolia (Asia Minor), to the Caucasus, northern Iran, and Crimea. In the central-east and east region of the Rhodope Mountains in Bulgaria and Greece, extensive hybridization zones are observed between oriental and European beeches (Kandemir and Zeki 2009; Czeczott 1932). Czeczott (1932) created a distribution map of the species F. orientalis based on data from the literature and field information, both related not only to the identification of individuals but also based on paleo-pollen information. In Romania, it was only reported at Luncaviţa in Valea Fagilor forest. Kandemir and Zeki (2009) updated the distribution map of the species F. orientalis based on genetic studies through which they verified, validated, and completed with new areas. The distribution patterns of the species in the south-eastern Balkans suggest that F. orientalis may occur on drier and warmer sites than F. sylvatica. According to the map of the oriental beech in Romania, the Luncaviţa area was confirmed and four more points were reported (three in the west of the country – the Banat region, and one in the east on the border with the Republic of Moldova) (Kandemir and Zeki 2009). Oriental beech is found in pure or mixed forest stands at altitudes ranging from 200 m to 2200 m; it grows on extremely varied relief, with erosion-tectonic and accumulation forms bordered by volcanic, glacier, and karst forms. Not surprisingly, the climate is also variable; rare annual precipitation in its southwestern part exceeds 2000 mm in the coastal area of the Black Sea (to 4000–4500 mm on the 1300–1400 m); in contrast, in the southwestern (lowland) part of the Caspian Sea coast, it rarely exceeds 150 mm. The mean annual air temperature in the Trans-Caucasian part of the Black Sea coast and Caspian Sea coast is 15°C, declining from south to north and with increasing altitude (with an average fall of 0.65°C per 100 m). The average annual rainfall is generally higher in the western portion of the eco-region, ranging from 1500 to 2000 mm in the western ranges along the Black Sea, and from 600 to 1000 mm in the eastern and southern portions of the range (Zazanashvili et al. 2000). Studies of genetic structure corroborated with phenological data for F. sylvatica have demonstrated that climate change threatens to outpace forest migration, making trees’ survival dependent on them (Matthew et al. 2018).

In Romania, in 1953, during the elaboration of an extensive work in which the species of vascular cryptogams covering the surface of Romania were described, two beech species were mentioned (F. sylvatica – European beech and F. orientalis – Oriental beech). The study was developed based on the morphological characteristics of the respective species and revealed 10 varieties for the European beech and 3 for the Oriental beech. F. orientalis hybridization with F. sylvatica leads to the formation of the hybrid: FAGUS × TAURICA Popl. (Fagus sylvatica × Fagus orientalis), with a popular name: Crimea beech (Nyarady, 1953). In 2005, Clinovschi reviewed both species and described two more subspecies for F. sylvatica. Clinovschi (2005) also divided the 15 varieties into 4 classes accordingly: (i) the shape of the crown of the tree, (ii) the leaf characteristics, (iii) the cup characters, and (iv) the bark characters. For Oriental beech or Caucasian beech (F. orientalis) (Lipsky), it does not confirm the presence of the three varieties; instead, it confirms the presence of the hybrid Crimea beech. Two years later, Ştofletea and Curtu carried out a revision that mentioned the presence of the F. sylvatica only in Romania, with 17 varieties divided into four categories, taking into account the same four characteristics similar to Clinovschi (Sofletea and Curtu 2007). Several climatic and edaphic ecotypes are present in Romania, Bucovina beech (cold climate), Banat beech (thermophilic climate), the beech from the Apuseni Mountains (thermophilic climate), Dobrogean beech (warm and dry climate), high-altitude beech (Vâlcan, Parâng, Godeanu), and low-altitude beech (Valley of the Danube, Snagov).

In Romania, the European beech occupies about 2 million hectares (32% of Romania’s forested area), it is found from 300–500 m to 1200–1400 m, frequently in hilly and mountainous areas; on wet valleys, it descends to 150–200 m on the Cerna and Danube Valleys to 60–100 m (Clinovschi 2005; Sofletea and Curtu 2007). In the vast area, it forms pure stands on large areas or mixtures with sessile oak, hornbeam, fir, and spruce. Outside of its continuous area, F. sylvatica is still insular in the following hill zones: Olt-Bucovăţ Forest (near Craiova), Stărmina Forest (Hinova-Turnu Severin Region), Bucoviciorul (Dolj-Brabova Region), Dobrogea Luncaviţa on Valea Fagilor (Mountains Măcin Region), and Mrea Cilic (Tulcea Region). This species goes down to the plain area: Transylvania Plain (Rămeţi Forest in the vicinity of Silvaşul de Câmpie, Sărmaşel Forest near Luduş) and Muntenia Plain (Snagov, Ciolpani, Hereasca and Gheorghiţa Forests) where rare specimens of the beech are scattered in mixed forests. (Nyarady 1953). On analyzing the distribution of F. sylvatica elaborated by Groß in 1934, it is observed that, on the territory of Romania, there are 12 island areas grouped into 3 regions (Groß 1934).

For F. orientalis, Romania represents the limit of the range. Nyrady (1953) signaled this species in south-west of the country-Banat at Sasca Montană, in Nera Valley, Sviniţa-Herculane, Plavişeviţa, Dubova, Ogradena, and Ţarcu, Cozia, Ciucaş, Măcin Mountains (Dobrogea-Luncaviţa-Valea Fagilor), in Muntenia Plain at Conţeşti, Nişcov Valley-Buzău country (Nyarady 1953). The forest with Oriental beech (F. orientalis) present in Romania, is the result of migration to central eastern Europe in interglacial period (Magri 2008).

Dămăceanu et al. (1964) carried out a study of the forests in the most arid area of Romania called Dobrogea. In the sub-zone of the sessile oak that belongs to the forest vegetation of Northern Dobrogea, in one unique place (in the Valley of Beeches, a tributary of the Luncaviţa River), there is an arboretum with a large proportion of beech (Damaceanu et al. 1964). Although at a very low altitude (200 m), in an arid area, the presence of the beech is accompanied by other plant species typical of the beech zone: herbaceous – Galium silvaticum, Aspidium filix mas, Heracium sp., Festuca sp., Lactuca muralis, Geranium robertianum, Luzula silvatica, Pulmonaria officinalis, Asperula adorata (Galium odoratum), Sanicula europea, Asarum europaeum, Stellaria sp., Mycelis muralis, Dentaria bulbifera, and Mercurialis perennis; wood species – Tilia parvifolia, Ulmus montana, Populus tremula, Salix caprea, Cerasium avium, Sorbus aucuparia, Fraxinus ornus, Viburnum lantana, Comus sanguinea, Crataegus monogyna, and Rhamnus frangula (Georgescu 1928; Gheorghe 2008).

These species are associated with plant communities typical of the European forest habitats from the annex of the Habitats Directive 92/43EEC:9130 Asperulo-Fagetum beech forests; it is present in 90 Romanian Natura 2000 sites, of which only 12 overlap the beech forests in the extra area. It has four facies and correspondence in Romanian classification with (I) R4118 Dacian beech forests and hornbeam with Dentaria bulbifera; (II) R4119 Dacian beech forests and hornbeam with Carex pilosa; (III) R4120 Mixed Moldavian forests of beech and silver linden with Carex; (IV) relict stands of collinar neutrophilous beech forests of the Măcin Mountains of Dobrogea, Romania, are the priority habitat 91X0*Dobrogean Beech forests (European Commission 2013). According to Petrescu (2007), the 91X0*Dobrogean beech forest habitat is present here. It is considered that this habitat, in its typical form of dominant beech forest, is unique in the country and Europe, being found only in the Măcin Mountains, on extremely small areas, around 2 ha, most of which are included in the Natural Reserve Valley of Beeches-Măcin Mountains Natural Park. The area of the beech is greater than 2 ha, respectively, at least 5 ha; in the rest of the reservation and its surroundings (area of 3 ha), the beech is co-dominant or disseminated within linden and hornbeam forests. In the past, the area was larger, but it has been reduced due to human activities (Petrescu 2007). The presence of the habitat 91X0*Dobrogean Beech forests is also mentioned in the standard form of the Natura 2000 network site ROSCI0123 Munții Măcinului, where the F. taurica hybrid is also signaled. In the composition of this habitat are present the following species: trees – Fagus sylvatica, F. taurica (syn. F. taurica var. dobrogica), Tilia tomentosa, T. cordata, Carpinus betulus, Populus tremula, and Ulmus glabra; herbaceous – Potentilla micrantha, Scutellaria altissima, Carex pilosa, Cystopteris fragilis, Carpesium cernuum, Melica uniflora, Milium effusum, Polygonatum multiflorum, Brachypodium sylvaticum, Bromus ramosus, and Stacys sylvatica. Apart from the Dobrogea forests, the beech has also been identified in four more areas below the altitude of 250 m. The habitat in these areas, where beech is present, is slightly different from the point of view of specific composition. In these areas, the habitat (91Y0 Dacian oak and hornbeam forests is present with the following composition: trees – Carpinus betulus, Quercus petraea, Q. robur, Q. cerris, Q. frainetto, Fagus sylvatica, F. orientalis, Pyrus eleagrifolia, P. malus, Fraxinus excelsior, Tilia tomentosa, T. cordata,, Populus tremula, and Ulmus glabra; shrubs – Lonicera caprifolium and Cotinus coggygria; herbaceous – Stellaria holostea, Carex pilosa, C. brevicollis, Carpesium cernuum, Dentaria bulbifera, Galium schultesii, Festuca heterophylla, Ranunculus auricomus, Lathyrus hallersteinii, Melampyrum bihariense, Aposeris foetida, Helleborus odorus, and Ruscus aculeatus) is different from the habitat 91X0*Dobrogean Beech forests present in Dobrogea. In the composition of the Romanian insular forest beech present in Banat, Oltenia, in the south of Moldova, and Dobrogea, two subspecies of the F. sylvatica dominate, namely, ssp. sylvatica, with shorter leaves, and ssp. moesiaca, with longer leaves, and sporadic is present in the F. orientalis species (Clinovschi 2005). Among the first signs of the presence of the F. orientalis, in Romania, was that of Grinţzescu, information taken by Czeczott (1932) and used in the elaboration of the distribution map of the species. In Romania, sporadic individuals of F. orientalis were identified first time only in the Luncaviței Valley (Tulcea Region) (Grinţzescu 1927). Because of the morphological differences being inconclusive and due to the lack of a PSR method, the author signals the presence of the species with certain reservations.

This study aims to explain the presence of beech in areas where pedo-climatic conditions are much different from the ecological optimum.

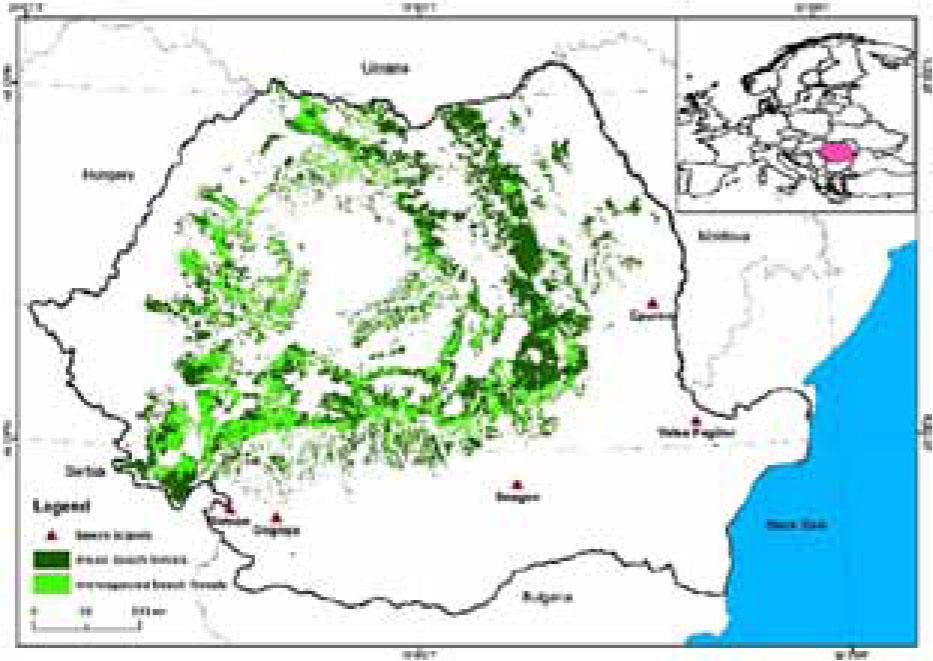

Five study zones were selected in Romania where beech can be found in the extra area: (I) Dobrogea at Luncaviţa Valley in Tulcea country – 77.72 ha, distributed in three plots: 67, 68, 69A (INCDS -, 2016); (II) Gogoşu – Filiaşi near Craiova in Dolj country – 23.57 ha (16C, 18B and 14J); (III) Stârmina – Drobeta Turnu Severin in Mehedinţi country – 62.40 ha (20A, 21A and 22A); (IV) Epureni Forest – on the border of Vaslui and Galaţi counties – 8.86 ha (8C, 13B, and 15C), and (V) Snagov Forest – near Bucharest in Ilfov county – 20.60 ha (99A, 99C, 99B, 100A, and 100B); each area having 1–5 plots except for the Snagov forest in which there were five of which in one the beech is poorly disseminated with a participation of ˂10% (Fig. 1). As the four plots had a beech participation of less than 10%, only 13 plots were analyzed in the study.

Map of the Romanian beech forests and positions of five study zones (Valea Fagilor, Gogoşu, Stârmina, Epureni, and Snagov forests) (Gancz et al. 2008) modified

This selection was based on five types of information sources: field trips, distribution maps at the European level for European and Oriental beech, the chorology description in guides for plant identification and books on dendrology, the forest planning studies, and Natura 2000 network information. The presence of beech in the composition of the selected forests was at least 10%. The following parameters were identified for each area: number of plots, surface of each plot, altitude, exposure, soil type, participation of beech in the composition of the forest, average age, average HDB, average height, and flora type. Tree height was measured using Vertex 5 (height–distance–angle), and the diameter was measured using a tree caliper; for age, regression lines between diameter and age were used.

The specific composition of each plot was established based on floristic surveys. Seventeen floristic surveys were carried out in the forests, one for each plot, and the size of each floristic survey was 500 m2. To describe the climatic/bioclimatic conditions of the study areas, 53 climatic and bioclimatic indices were calculated. Because for the study zones there are no weather stations with long-term records, the main climatic variables – air temperature and precipitation – are interpolated from climate data from the nearest stations. The annual climate data and bioclimatic variables were generated for each zone using Climate EU v4.63 based on zone-specific geographic coordinates and elevation (Marchi et al. 2020).

As proxies for growing season warmth, Tauto’s warmth index (WI) (Tauto 1991) and Holdridge’s annual bio-temperature (ABT) (Holdridge 1947) were calculated. With minimum winter temperatures, it was found to be important in controlling the distributional limits of plant species (Woodward and Williams, 1987). In order to express the coldness of an area, the mean temperature of the coldest month (MTCM) is used as a measure. Tauto’s coldness index (CI) (Tauto 1991) expresses the cumulative winter temperature, which is important for the northward/upward distributions of warm-temperate and tropical tree species (Tauto 1991; Fang and Lechowicz 2006). The annual mean temperature (AMT) and the mean temperature of the warmest month (MTWM) are important to explain the northward and upward distribution of tree species in the Northern hemisphere (Ohsawa 1990). The climatic continentality is a limiting factor on the distribution of tree species (Jingyun and Lechowicz 2006). The degree of climatic continentality is assessed using the annual range of monthly mean temperatures (ART) as well as Gorcynski’s continentality index (K).

Aridity indices are used to describe the aridity of regions in relation to their suitability for natural vegetation. In our study, the de Martonne aridity index (IDM) was calculated both monthly and annually to assess dry/humid conditions (Coscarelli et al. 2004) of study sites. The suitability of the climate for particular species and vegetation is also described by the Lang rainfall index (LRI), which expresses the degree of atmospheric humidity (Thornthwaite 1948; Stephen 2005), as well as the compensated summer ombrothermic index (CSOi) for the warmest months of the year. These indices were used for mapping the bioclimatic map of Europe (Salvador et al. 2011). The repartition of precipitation between the summer half year and winter half year describes the precipitation continentality or precipitation ratio (PR) in a particular area (Mikolaskova 2009). Ellemberg quotient (EQ, °C/mm) is a measure of the hygric continentality of the climate in a particular area, and it is a valuable index that was proposed to show the climatic limit of beech in Europe as well as its competitiveness with other tree species in mixed forests (Ellemberg 1988). This quotient has been used in studying the south-eastern continental limits of F. sylvatica in Europe (Mellert et al. 2016). In addition to estimating the impact of drought on beech and climate favorability of the area for it, the Mayr tetratherm index (MT) (Bokwa et al. 2021), forestry aridity index (FAI) (Führer et al. 2011), beech tolerance index (QBTI) (Berki et al. 2009; Rasztovits et al. 2011), and continentality Gams index altitudes, named Fagus favorability index (Rosenkranz et al. 1936; Michalet 1991), were applied. This index has been applied in forestry studies, and values lower than 4.5 were found to be optimal (Führer et al. 2011).

Using the MVSP program, similarity clusters were created in the 13 plots for both the structural parameters and the climatic indices.

All 13 plots are located at an altitude of less than 250 m above sea level, except for three plots; they have northern or north-east and north-west exposure. The northern exposure explains the presence of the European beech, this being an ombrophilous species. The type of soil is closely related to the type of flora: Cambisols allow the installation of flora dominated by the genera Asarum‒Stellaria, and Luvisols allow the installation of flora dominated by Carex‒Poa pratensis. Of the 13 parcels, 11 are mature forests whose average age of beech is over 100 years, the oldest being at an average age of 170 years. The average HDB and the average height of the trees in the study areas indicate low values of the size of the trees whose age exceeds 100 years, which indicates a physiological stress state of the trees, and a large part of the woody biomass is produced by photosynthesis (Tab. 1).

Structural parameters of study forests

| Plots–forest/parameters | 67 Valea Fagilor | 68 Valea Fagilor | 69A Valea Fagilor | 8C Epureni | 13B Epureni | 15C Epureni | 99B Snagov | 16C Gogoşu | 18B Gogoşu | 14J Gogoşu | 20A Stârmina | 21A Stârmina | 22A Stârmina |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface (ha) | 23.27 | 18.84 | 35.61 | 1.16 | 3.91 | 3.79 | 1.3 | 14.58 | 8.05 | 0.97 | 15.15 | 29.11 | 18.14 |

| Altitude (m) | 225 | 230 | 230 | 230 | 250 | 210 | 100 | 230 | 210 | 240 | 40–170 | 70–170 | 50 |

| Exposure | N | S-E | N | N | N-E | N-E | N-E | N-E | N-E | N-V | N-V (slope 30○) | V (slope 30○) | V |

| Cod Sol type | 3101 | 3101 | 3101 | 3101 | 3101 | 2101 | 2101 | 2201 | 2201 | 2212 | 2103 | 2115 | 2115 |

| Participation of beech % | 10 | 10 | 10 | 40 | 40 | 10 | 40 | 10 | 20 | 10 | 20 | 10 | 10 |

| Average age (years) | 140 | 140 | 140 | 120 | 120 | 110 | 170 | 70 | 80 | 110 | 150 | 150 | 150 |

| Average DHB (cm) | 52 | 52 | 48 | 46 | 46 | 46 | 68 | 34 | 40 | 34 | 50 | 50 | 56 |

| Average height (m) | 24 | 25 | 24 | h31 | 32 | 31 | 24 | 28 | 24 | 23 | 27 | 28 | 24 |

| Flora type | Asarum‒Stellaria | Asarum‒Stellaria | Asarum‒Stellaria | Asarum‒Stellaria | Asarum‒Stellaria | Carex‒Poa pratensis | Carex‒Poa pratensis | Carex‒Poa pratensis | Carex‒Poa pratensis | Festuca pseudovina | Carex‒Poa pratensis | Carex‒Poa pratensis | Carex‒Poa pratensis |

Soil Codes: Cambisols–Eutricambosol–typical, code-3101; Luvisols–Luvosol–typical, code-2201; Luvisols–Luvosol–stagnant, code-2212; Luvisols–Preluvosol–reddish, code-2103; Luvisols–Preluvosol–typical, code-2101; Luvisols–Preluvosol–mollic-reddish, code-115.

The beech in the extra area is present in two types of habitats: 91X0*Dobrogean Beech forests and 91Y0 Dacian oak & hornbeam forests; 91X0* is present in two arid areas: the Cambisols and Asarum‒Stellaria flora (Valea Fagilor and Epureni); and 91Y0 is present in three semi-arid areas on Luvosol (Snagov, Gogoşu, and Stârmina) and Carex‒Poa pratensis flora (Tab. 1, Fig. 2). The oriental beech is present in the Valea Fagilor, Stârmina, and Gogoşu forests, where, together with the European beech, they form islands. All three forests are in the area of Romania, where there is a local climate with Mediterranean influences, which explains the presence of oriental beech. The Snagov and Epureni forests belong to the silvo-steppe; only the European beech is present here, and the higher humidity conditions than in the Beech Valley Forest and the ecological plasticity of this species allowed its presence here. The Epureni and Stârmina woods are present in the major meadow of the rivers, and the Valea Fagilor is located on the slopes of the Luncavita River Valley. This positioning compensates for the lack of precipitation through local water circuits and the supply from the water table that is not far above the surface.

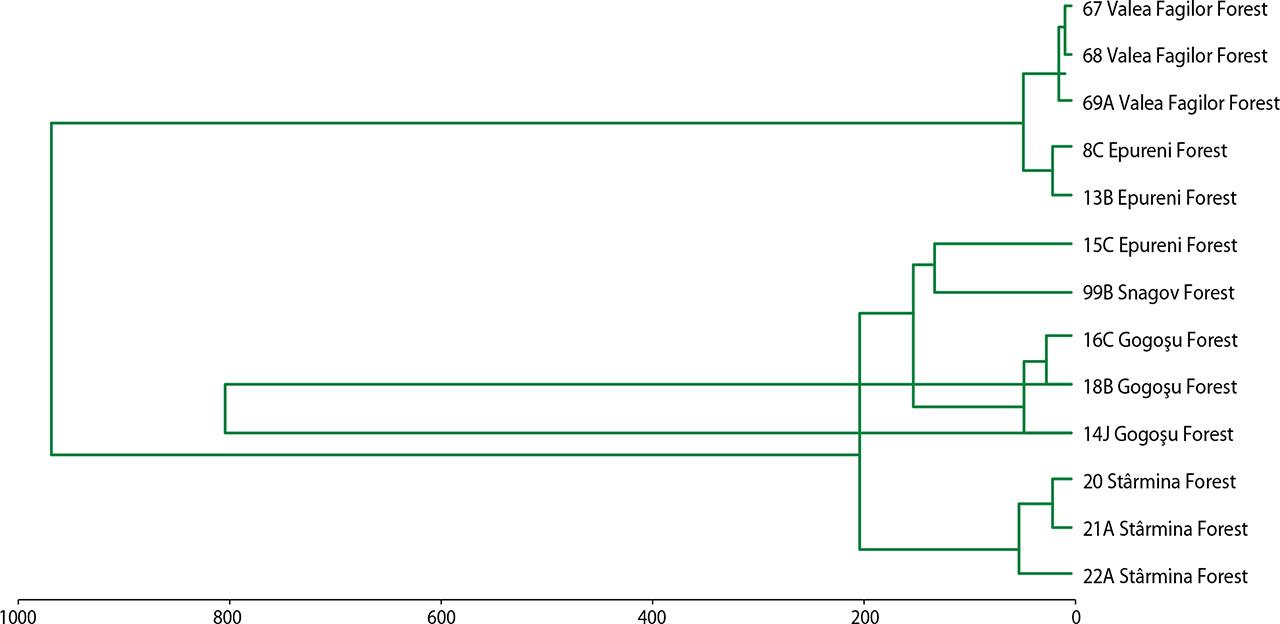

The similarity degree between 13 plots presents in the five study areas from the point of view of biological structural parameters (using the MVSP program)

In the case of four particular bioclimatic indices, our results show that there are no optimal ecological values for F. sylvatica. For all study zones, de Martonne aridity index values are less than 30, which corresponds to a moderately arid climate, even arid in Luncavița, while the optimal climate for beech is moderately humid (IDM: 35 ≤ I ≤ 40) (Satmari 2010). In terms of the Mayr Tetraterm, results show higher values than those that are optimal (13–18°C) (Satmari 2010) for beech. Except for the Snagov forest site, where the calculated continentality Gams index is greater than 1 and falls within the optimal range of 1–2 (Satmari 2010), for the other stations, the values are outside the ecological optimum for beech (Tab. 2).

Climatic variable, climatic and bioclimatic indices, and quotients that describe study sites for the period of 1901–2020

| Nr. Crt | Climatic variable, Index/quotient | Epureni Forest | Valea Fagilor Forest | Snagov Forest | Stârmina Forest | Gogoșu Forest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 1 | AMT (°C) | 9.9 | 10.5 | 10.7 | 10.8 | 10.8 |

| 2 | MTWM (°C) | 21.3 | 21.7 | 21.9 | 21.5 | 21.6 |

| 3 | MTCM (°C) | −3.1 | −1.9 | −2.4 | −0.8 | −1.7 |

| 4 | ART (°C) | 24.4 | 23.6 | 24.3 | 22.3 | 23.3 |

| 5 | AP (mm) | 524.7 | 479.2 | 586 | 614 | 613.6 |

| 6 | MJJA(°C) | 26.5 | 26.6 | 27.7 | 26.8 | 26.9 |

| 7 | PJJA (mm) | 189.4 | 153 | 201.3 | 190.6 | 192.4 |

| 8 | MTVS (°C) | 17.5 | 17.7 | 18.1 | 17.8 | 17.9 |

| 9 | APVS (mm) | 334.2 | 278.8 | 362.1 | 354.1 | 354.8 |

| 10 | DD<0 | 356.7 | 276 | 294.7 | 215.6 | 256.3 |

| 11 | DD>5 | 2602.4 | 2673.8 | 2756.3 | 2698.9 | 2724.9 |

| 12 | DD<18 | 3234.3 | 3076.1 | 3029.6 | 2932 | 2965.2 |

| 13 | DD>18 | 389.8 | 421.7 | 448 | 388.5 | 410.5 |

| 14 | NFFD | 254.2 | 264.9 | 258.6 | 273.2 | 269.3 |

| 15 | FFP | 193.7 | 202.9 | 195.4 | 206.3 | 203.7 |

| 16 | bFFP | 100 | 95.9 | 99.4 | 93.4 | 94.6 |

| 17 | eFFP | 293.8 | 298.9 | 294.7 | 299.7 | 298.7 |

| 18 | Eref | 785.7 | 790.9 | 866.9 | 844.9 | 844.1 |

| 19 | CMD | 378.4 | 423.8 | 404.6 | 375.4 | 375.65 |

| 20 | Q | 56.52 | 51.9 | 59.9 | 67.7 | 65.5 |

| 21 | SDI | 7.14 | 5.75 | 7.3 | 7.1 | 7.15 |

| 22 | WI | 80.7 | 83.4 | 85.4 | 83.9 | 84.1 |

| 23 | ABT | 10.4 | 10.7 | 10.9 | 10.9 | 10.9 |

| 24 | CI | −21.6 | −17.8 | −17.6 | −14.3 | −15.7 |

| 25 | K | 37.21 | 38.8 | 36.2 | 33.7 | 36.2 |

| 26 | R | 1.75 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.36 | 1.37 |

| 27 | *EQ | 40.6 | 45.3 | 37.4 | 35 | 35.2 |

| 28 | * IdM | 26.4 | 23.4 | 28.3 | 29.5 | 29.5 |

| 29 | IdMVS | 24.4 | 19.3 | 25.6 | 25.8 | 25.7 |

| 30 | I | 53 | 45.6 | 54.8 | 56.9 | 56.8 |

| 31 | *FAI | 6.82 | 8.63 | 6.46 | 6.68 | 6.69 |

| 32 | QBTI | 14.85 | 12.76 | 13.8 | 13.7 | 13.6 |

| 33 | *cot G | 0.8166 | 0.74 | 1.074 | 0.96 | 0.9 |

| 34 | *MT | 19.5 | 19.7 | 20.02 | 19.5 | 19.7 |

| 35 | CSOi | 12.7 | 10.3 | 13.6 | 13.3 | 13.2 |

AMT – annual mean temperature; WI – warmth index; MTWM – mean temperature of the warmest month; MTCM – mean temperature of the coldest month; ART – annual range of mean temperature or continentality (°C); AP – annual precipitation; MJJA – mean of the maximum temperature in summer months (June–August); PJJA – amount of precipitation during summer (June–August); MTVS – mean temperature during the vegetation season (April–September); APVS – amount of precipitation during the vegetation season (April–September); DD < 0 – degree-days below 0°C, chilling degree-days: DD > 5 – degree-days above 5°C, growing degree-days; DD < 18 – degree-days below 18°C, heating degree-days; DD > 18 – degree-days above 18°C, cooling degree-days; NFFD – the number of frost-free days; FFP – frost-free period; bFFP – the Julian date on which FFP begins; eFFP – the Julian date on which FFP ends; Eref – Hargreaves reference evaporation; CMD – Hargreaves climatic moisture deficit; Q – the pluviometric quotient/Emberger quotient; SDI – summer drought index; WI – Kira’s Warmth Index; ABT – Holdridge’s annual biotemperature; CI – Kira’s coldness index; K – Gorcynski’s continentality index; R – precipitation continentality/precipitation ratio; EQ – Ellemberg quotient; IdM – annual de Martonne aridity index; IdMVS – vegetation season de Martonne aridity index (April–September); LRI – Lang rainfall index; FAI: forestry aridity index; QBTI – beech tolerance index; cot G (also named Fagus favorability index/continentality Gams index altitude); MT – Mayr tetratherm; CSOi – Compensated Summer Ombrothermic index;

– indices in grey and asterisk have values outside the ecological optimum for beech.

There are also significant deviations in the case of the forestry aridity index (FAI), whose value ranges between 6.46 and 8.63, compared to the optimal one (4.75) (Führer et al. 2011).

In the case of the Ellenberg quotient (EQ), the obtained results (Tab. 2) deviate even more from the published studies. Thus, it was identified that, in Central Europe, the lower precipitation threshold for beech is 550 mm, and if the EQ values fall below 15, then the more thermophiles and drought-resistant deciduous trees relinquish to habitats where beech becomes the most vigorous tree in natural woodland (Ellemberg 1988).

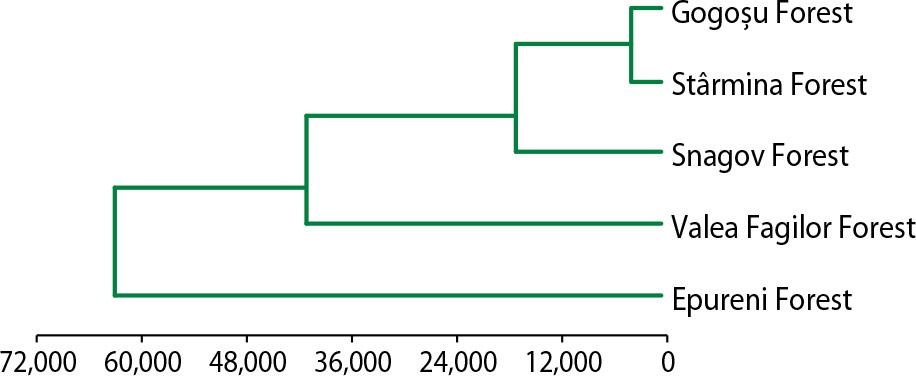

According to Jahn (1991), EQ values below 20 reveal an optimum favourability for beech, describing a pure “beech climate”, but, for the studied sites, EQ values vary between 35 and 45. However, studies show that the competitive vigour of beech decreases between 20 and 30, and in European regions where EQ is over 30, beech disappears, although it is not excluded to occur in the oak-hornbeam woods formed in the warmest and driest areas located at lower altitudes (below 200 m) with the mean air temperature in July ranging from 18 to 20.1°C and annual precipitation amount ranging from 480 to 550 mm (Ellemberg 1988), which are climatic conditions almost similar to those of the studied sites. However, according to Bokwa et al. (2021), when EQ > 40, beech cannot survive. The great diversity of climatic index values (Tab. 2, Fig. 3) explains the morphological and ecological variety of the beech, but also the genetic plasticity that allows it to create those varieties.

The similarity degree between the five forests from the climate point of view (using the MVSP statistics program)

Comparing the classification of the five forests from the point of view of structural parameters (Fig. 2) with the classification from the climate point of view (Fig. 3), the forests were grouped in the same way, which proves that the structure of a forest is conditioned by pedo-climatic conditions.

The Romanian beech islands in the extra range are the result of the collaboration of two processes: the ecological, morphological, and genetic plasticity of the F. sylvatica species and the local pedo-climatic conditions that allowed the migration of the F. orientalis.

On account of the analysis of the climatic and bio-climatic indices, structural parameters, and soil type, it was concluded that the structure of the beech islands is primarily influenced by the pedo-climatic conditions. The European beech also grows in areas where the pedoclimatic conditions do not represent the ecological optimum of this species, which demonstrates a great ecological plasticity. This assertion is also supported by Ştofletea and Curt, who make a description of the presence of 17 subspecies and varieties; the most important are two subspecies: F. sylvatica ssp. sylvatica and F. sylvatica ssp. moesiaca, the latter being present in Banat, Oltenia, and Dobrogea and is adapted to conditions of low humidity and high temperatures. Outside of the optimal ecological conditions, in arid areas or with a higher thermal regime, the European beech occupies small insular areas, being mixed with other tree species such as Carpinus betulus, Quercus petraea, Q. robur, Fraxinus excelsior, Tilia tomentosa, T. cordata, Populus tremula, Ulmus glabra, especially with F. orientalis with which it can hybridize, as in the case of Valea Fagilor Forest, where it forms Crimean beech FAGUS × TAURICA Pop. (Fagus sylvatica × Fagus orientalis). These beech adaptation mechanisms that created these beech islands have determined the appearance of unique habitats present only in Romania (91Y0 Dacian oak and hornbeam forests and 91X0*Dobrogean beech forests). In the context of climate change, the morphological variability of the species of the genus Fagus, as well as the genetic and ecological plasticity, gives this genus the possibility of adapting to the new pedo-climatic conditions and expanding the range of some thermophilic beech species.