A digital twin can be described as a virtual model designed to replicate a real object to a degree sufficient for its intended purpose. According to one common definition, a digital twin consists of three key elements: the physical object, its virtual representation, and the data that connects them (American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, 2020). To satisfy these conditions, extensive testing of the real object must be carried out, and the results should be stored within the virtual model. Once the digital twin accurately reflects the real object, it can be used to generate valuable insights into the real object’s current state, analyze efficiency issues, and develop potential improvements that may later be implemented in the physical counterpart (WSU Strategic Communication, 2021; Kraft, 2021). Other applications include lifecycle management, such as recording the history of detected damages or defects across a series of components and developing repair procedures for recurring issues (Glaessgen & Stargel, 2012). While creating and maintaining a digital twin requires an initial investment and continuous data exchange with the physical asset, digital twins are often commercially viable due to their potentially high return on investment (ROI) (McMahon, 2022).

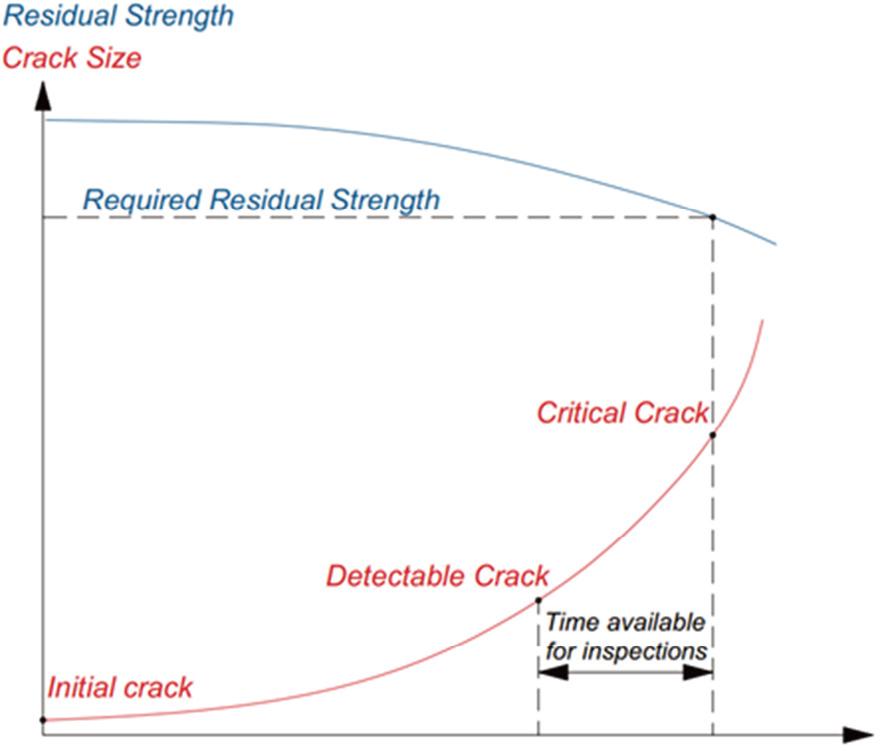

Any mechanical structure subjected to cyclic loading will eventually suffer fatigue, which can lead to failures, accidents, and financial losses. The European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) address this issue in their certification regulations (CS 25.571 and FAR 25.571, respectively) (European Union Aviation Safety Agency, 2007; Federal Aviation Administration, 2023). These sections of the airworthiness documentation regulations require designers to identify locations to be inspected and provide detailed guidelines on the frequency, scope, and methods of inspection. Furthermore, designers must establish damage criteria by determining the detectability of defects using specific inspection techniques, defining the minimal detectable crack size, and estimating the likely damage growth rate. The progression of damage and its detectability can be represented using the damagetolerance graph proposed by Brot (2012).

Figure 1 shows the timeframe within which inspections must be carried out to comply with airworthiness regulations. To enable such inspections, non-destructive testing (NDT) procedures have been developed. These methods make it possible to examine the continuity of the material without risking damage to the tested part. Moreover, NDT techniques are often convenient for inspectors, as in many cases the tests can be performed with the part still installed on the aircraft. However, according to EN-4179 (Polish Committee for Standardization, 2022) and NAS410 (Aerospace Industries Association, 2020), testing must be performed by certified personnel, as interpreting the results requires specialized knowledge and experience.

The damage-tolerance concept for ensuring sufficient service life, proposed by Brot (2012).

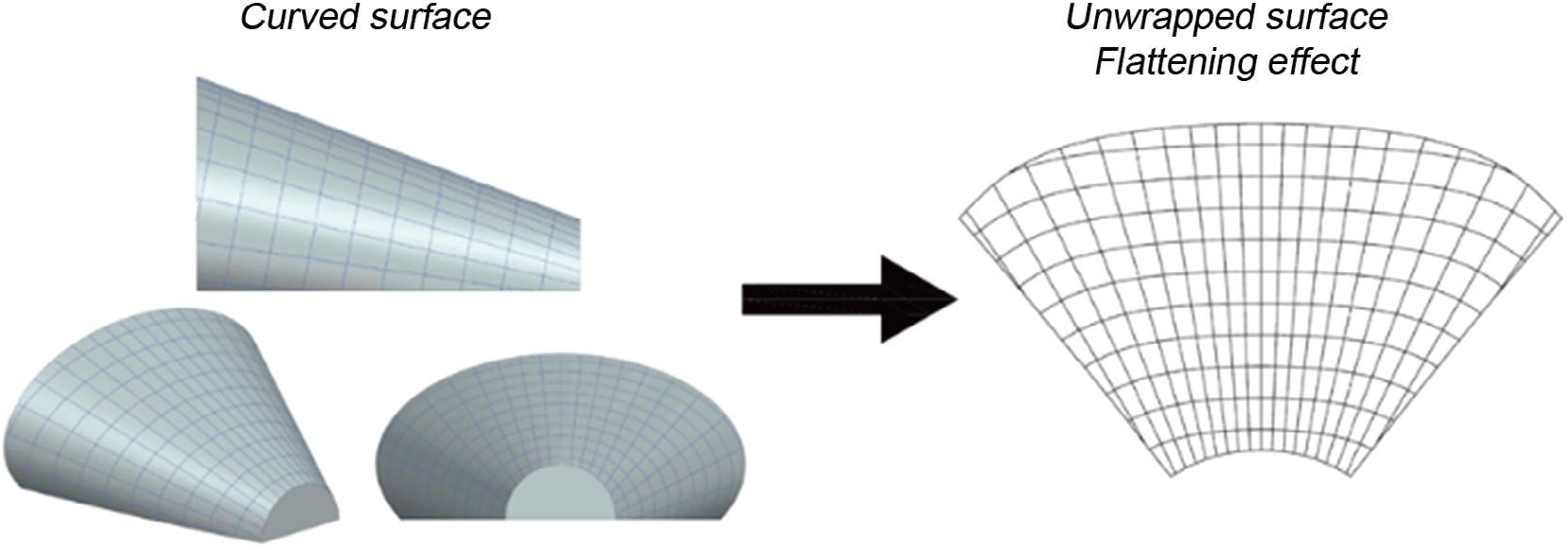

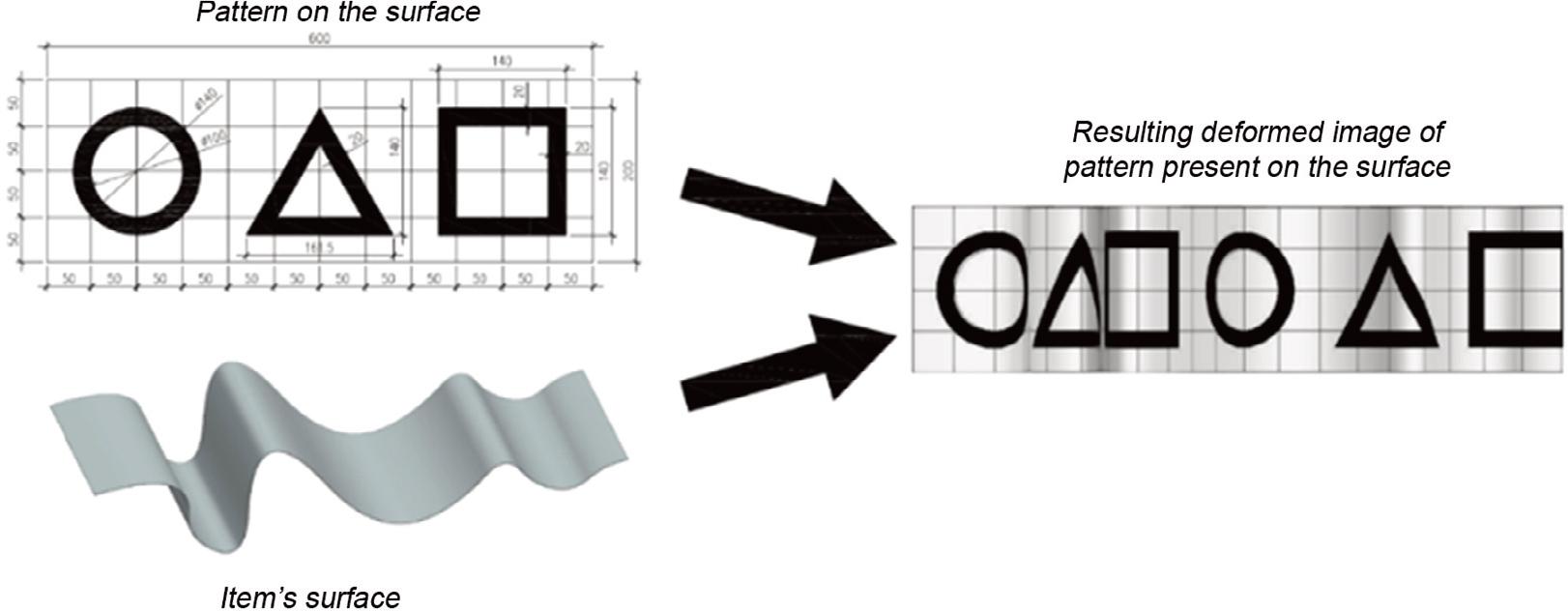

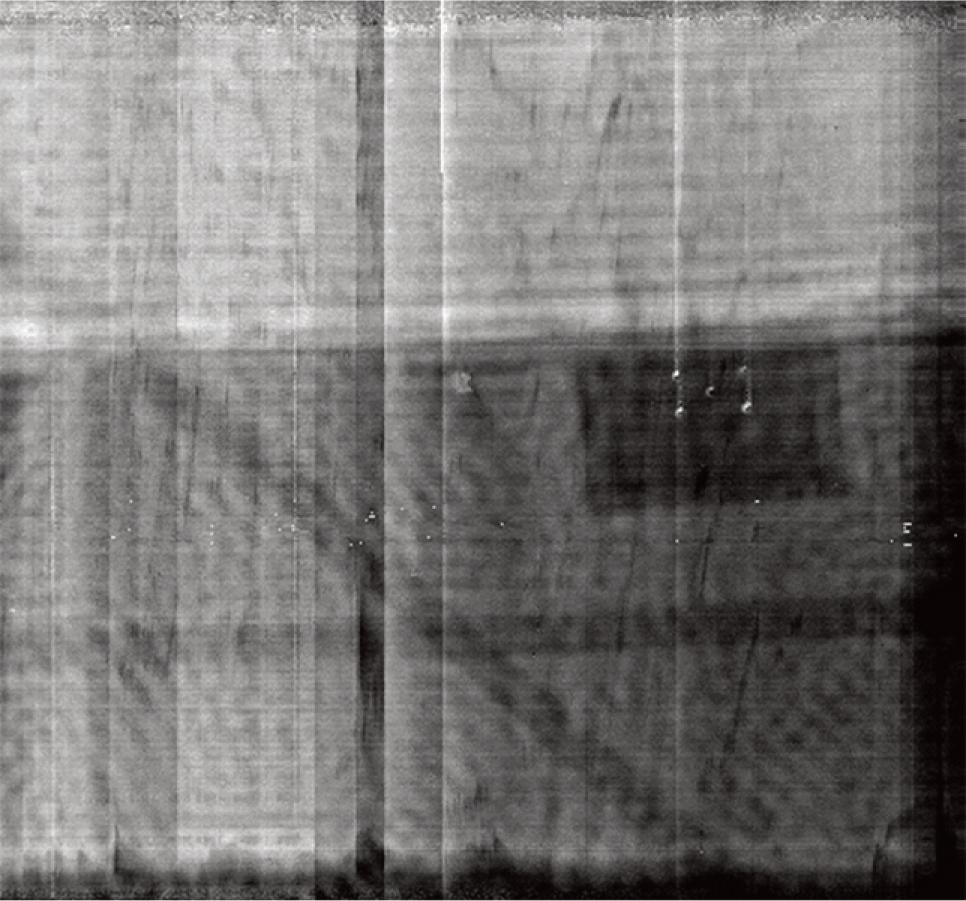

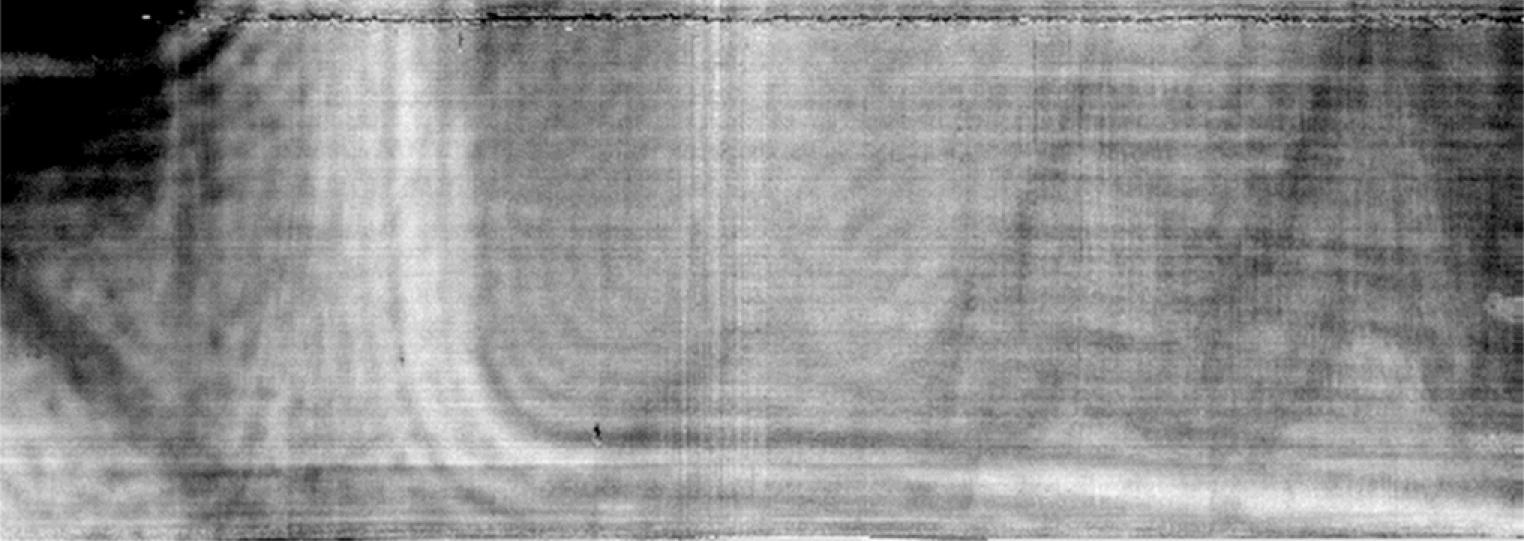

The results obtained from non-destructive testing depend on the method used. While PT and MT directly provide visible indications of defects on an item’s surface, other techniques, such as UT and ET, produce real-time charts representing the collected data. With the currently available technology, however, it is possible to convert a set of UT outputs into a bitmap image that highlights variations in material thickness or continuity. The resulting image more closely resembles outputs from optical methods such as TT, RT, and ST. Representing test results in the form of images is advantageous, as the visualized area is larger, making potential defects easier for personnel to detect. Additionally, estimating the size of discontinuities becomes more straightforward, since areas suspected of damage do not need to be examined point by point when they are clearly visible on the generated image or bitmap. Nevertheless, while a tested item with a flat surface produces an image from TT or a UT-generated bitmap that is nearly an exact representation of the surface, this does not hold true for curved surfaces. Images of non-planar faces become distorted depending on how the data is collected—either along the surface or as a projection of it. Examples of possible deformations are shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Demonstration of the flattening effect when an image is collected along a surface (as is the case for UT). It can be observed that the flattening primarily affects the unwrapped surface near the edges.

Demonstration of the flattening effect, when an image is collected as a projection of the surface (as is the case for TT).

It is clearly visible that the curvature of the surface introduces image deformation. One possible solution to this problem is the application of CAD software and models, which can serve as a base for displaying the results. If the data is projected appropriately onto the model surface, this approach would not only eliminate image deformation but also reduce the cognitive load required from the inspector, thereby minimizing the risk of human error and ensuring that potential damage is not overlooked (Rehbein et al., 2022). Moreover, since the obtained image is positioned directly on the model, there is no need to mark the damage physically on the object, meaning that the inspector does not have to access the component in person to determine where the test was performed.

This suggests that qualified inspectors would no longer need to be present on-site during testing. Instead, they could analyze the results remotely using CAD models, potentially lowering testing costs by reducing the need for inspectors to attend every inspection of an aircraft. Remote diagnostics are already common in fields such as medical science and other branches of engineering, and several companies are developing solutions to support remote diagnostics in aircraft maintenance; however, such systems are still not commonly adopted (Ithurralde, 2022).

Another advantage of using CAD models to display inspection results is that these models can function as a database for recording defects detected in individual components. If a defect is identified, inspectors could compare the current scan with previous inspection data to determine whether any early indications of damage were missed earlier. Furthermore, by using these models to store scans for an entire fleet of components, fleet operators (e.g., airlines, military organizations) or component manufacturers could analyze the collected data to improve designs or optimize repair procedures. Access to such data, combined with the ability to monitor defect trends over time across a population of parts, could provide a valuable tool for project control within Product Lifecycle Management (PLM).

Considering the potential benefits that digital twins can bring to supporting Product Lifecycle Management (PLM), the authors decided to develop and propose a general scheme for implementing a digital twin that integrates NDT data within a single CAD software environment. All details regarding the steps included in the proposed scheme will be described and discussed to provide the reader with a clear understanding of the reasoning behind the suggested solutions. Furthermore, to demonstrate the feasibility of the proposed approach, the scheme will be applied to create a new DT of an existing part. The final outcome of this investigation serves as a proof of concept presented in this paper.

The idea of implementing digital twins is rapidly gaining popularity among researchers working across various scientific fields. However, since the term “digital twin” has a fairly broad definition, only a portion of the available literature is directly relevant to the topic of this paper. Digital twins in the form of digital models that store information about an item’s technical condition over time are already widely used in civil engineering. Although the concept is not explicitly referred to as a “digital twin,” Building Information Modelling (BIM) serves a similar purpose, as its main objective is to store all technical data related to a building. Because BIM software is commonly used in the design process, some proposals have emerged to integrate NDT visualization directly into the software (Schickert et al., 2022).

Schickert et al. (2022) argue that using a digital model to present NDT results is highly advantageous, as both the design data and up-to-date information about the building’s condition can be stored in a single platform. This approach is convenient for civil engineers already familiar with the software and ensures a proper flow of information between design teams and construction sites.

Wichita State University’s (WSU) National Institute for Aviation Research (NIAR), in cooperation with the United States Air Force (USAF) and Lockheed Martin, is participating in a project aimed at preparing a digital twin of the F-16 Fighting Falcon fighter jet (WSU Strategic Communications, 2021). The project, sponsored by the Air Force Life Cycle Management Center (AFLCMC), seeks to extend the operational life of F-16 aircraft in the USAF fleet. The work involves reverse engineering by disassembling and scanning two aircraft, after which NIAR intends to create detailed 3D models of every part, enabling future modifications and adjustments. The institute uses Dassault Systèmes Catia V to store all components in a full-scale F-16 CAD assembly (Vinoski, 2021). The final model is expected to include all structural elements and larger systems such as hydraulics, fuel, and environmental control. The project aims to enable future F-16 upgrades while reducing lifecycle costs.

The full-scale F-16 digital model is also expected to serve as a valuable fleet management tool. With a fully digitalized design, fewer aircraft would need to be removed from flight schedules for testing new solutions, as modifications could first be simulated on the virtual model. Moreover, the availability of a comprehensive digital twin allows engineers to design and evaluate potential upgrades in advance, minimizing unnecessary work on real aircraft (WSU Strategic Communications, 2021).

In addition to the F-16 project, WSU NIAR is also working on the digitalization of other legacy aircraft designed before the widespread adoption of CAD software (Vinoski, 2021). The institute has created 3D models of the B-1 Lancer bomber (WSU Strategic Communications, 2022) and the UH-60L Black Hawk helicopter (WSU Strategic Communications, 2020), excluding their engines. As with the F-16, the airframes were disassembled and scanned part by part using 3D laser scanners. While the purpose of creating the B-1 Lancer digital twin was similar to that of the F-16 project, the digitalization of the Black Hawk was carried out at a higher level of detail. The helicopter’s airframe underwent structural testing to validate the resulting 3D models of its components (WSU Strategic Communications, n.d.). Overall, WSU NIAR and USAF efforts focus on providing advanced tools for fleet lifecycle management, enabling better oversight of older aircraft through updated digital documentation and simultaneous development of modifications aimed at preventing future obsolescence.

Rehbein et al. address the problem of missing links between physical structures and NDT results (Rehbein et al., 2022). In their paper published in the Journal of Nondestructive Evaluation, they propose solutions for integrating UT testing data with an existing 3D model of a helicopter’s fuselage tail. As part of the NDE 4.0 concept derived from Industry 4.0, the authors aimed to provide inspectors with a digitally enhanced tool for non-destructive testing and evaluation. To achieve this, they developed a demonstrator that uses mixed reality to overlay UT data onto a virtual representation of the real object in real-time, aligning the physical part with its 3D model in space so that scanning progress and results can be monitored live.

Furthermore, the obtained UT data, represented as colored textures mapped onto the virtual model, can be analyzed in Virtual Reality (VR) after testing, eliminating the need for constant physical access to the inspected part. For implementation, Rehbein et al. used the Unity game engine due to its mixed-reality capabilities and built-in UV mapping tools essential for displaying test results accurately. The authors argue that their approach could reduce inspector workload, improve data quality, and overcome the flattening issues seen when visualizing defects on curved surfaces. By storing bitmap results directly on the 3D model’s texture, temporary surface markings are no longer required, and the linkage between test data and the digital model becomes permanent, enabling future evaluations at any time. They also suggest that further development of their demonstrator may enable remote assistance and real-time supervision of UT inspections by certified experts, facilitating off-site analysis of NDT results. Importantly, the integration of NDT data into digital models creates a stronger foundation for improved Product Lifecycle Management (PLM), one of the central goals of Industry 4.0.

Researchers from the AGH University of Science and Technology in Kraków, in collaboration with MONIT SHM, have proposed another innovative approach aimed at enabling faster and more precise thermographic inspections of composite structures (Hellstein & Szwedo, 2016). By combining infrared (IR) cameras with 3D scanners, they introduced the concept of real-time 3D thermography. Their paper presents the complete workflow for implementing 3D temperature mapping, including data collection, image and scene processing, image projection, and ray-tracing visualization.

The authors address several technical challenges, such as correcting image distortions caused by wide-angle IR lenses, synchronizing real-time acquisition of depth files, generating accurate 3D models, and ensuring hardware calibration. The result of their research is the development of IR3D Analysis, a novel method applicable to both passive and active thermography. The algorithms supporting IR3D Analysis are provided as a module within the ThermoAnalysis software offered by MONIT SHM.

Although the method was initially designed for real-time integration of depth data with thermographic measurements, in the presented case study of a boat hull, the mapping onto the 3D model was performed during postprocessing. The authors note that real-time camera positioning using cloud fusion algorithms significantly increases hardware requirements, so they opted to generate a single 3D model per analysis. All prepared 3D thermograms were mapped onto the same pre-generated 3D model, created before testing began.

Hellstein and Szwedo (2016) emphasize that the 3D thermograms produced by IR3D Analysis provide inspectors with valuable contextual information about the measurement environment and precisely pinpoint the location of detected defects. Additionally, since TT data is mapped onto a true-to-scale 3D model, inspectors can directly extract accurate dimensions from the digital model. As a result, discontinuities can be measured with millimeter-level precision, improving both diagnostic accuracy and reporting consistency.

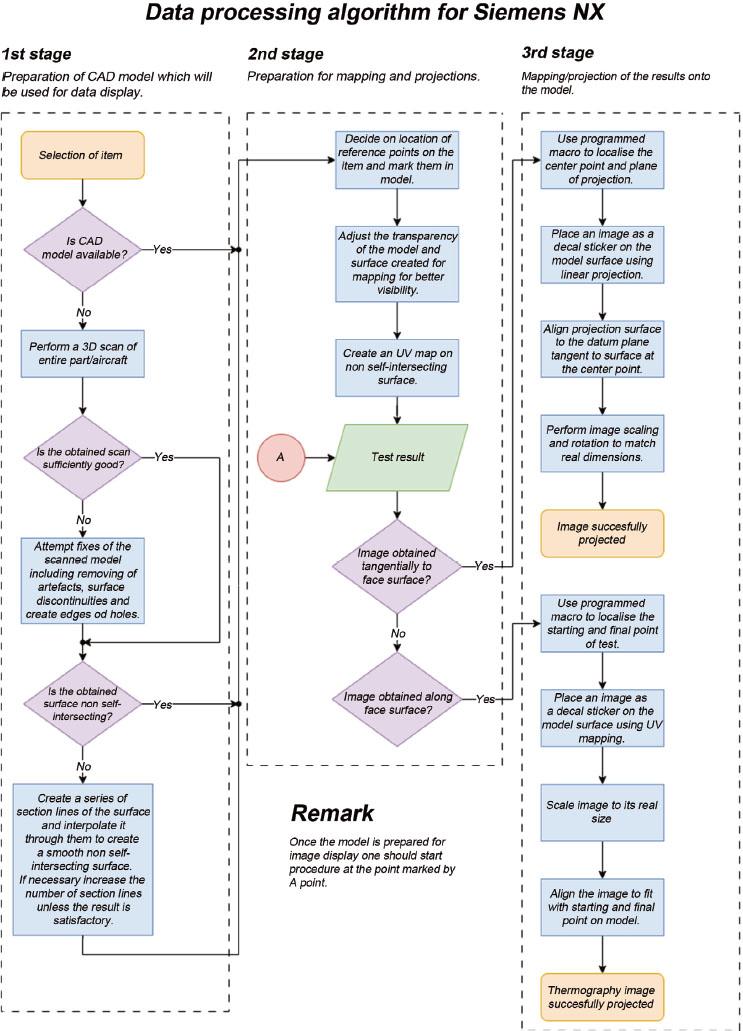

The workflow scheme presented in this paper can be applied to implement a digital twin of almost any part using most software platforms that support 3D modeling, such as game engines, graphic design tools, and other modeling environments. However, one of the key assumptions regarding the functionality of the designed digital twin was that the entire model, along with all data collected during testing, should be stored and managed within a single software environment. An additional requirement was that the chosen software should be commonly used by engineers in their everyday practice. These constraints led to selecting Siemens NX, a Computer-Aided Design (CAD) software widely adopted in engineering applications. Consequently, the workflow described in this chapter and illustrated in Figure 4 includes several steps that are specific to how Siemens NX operates and may not directly apply to other software platforms.

Data processing scheme for preparing a digital twin.

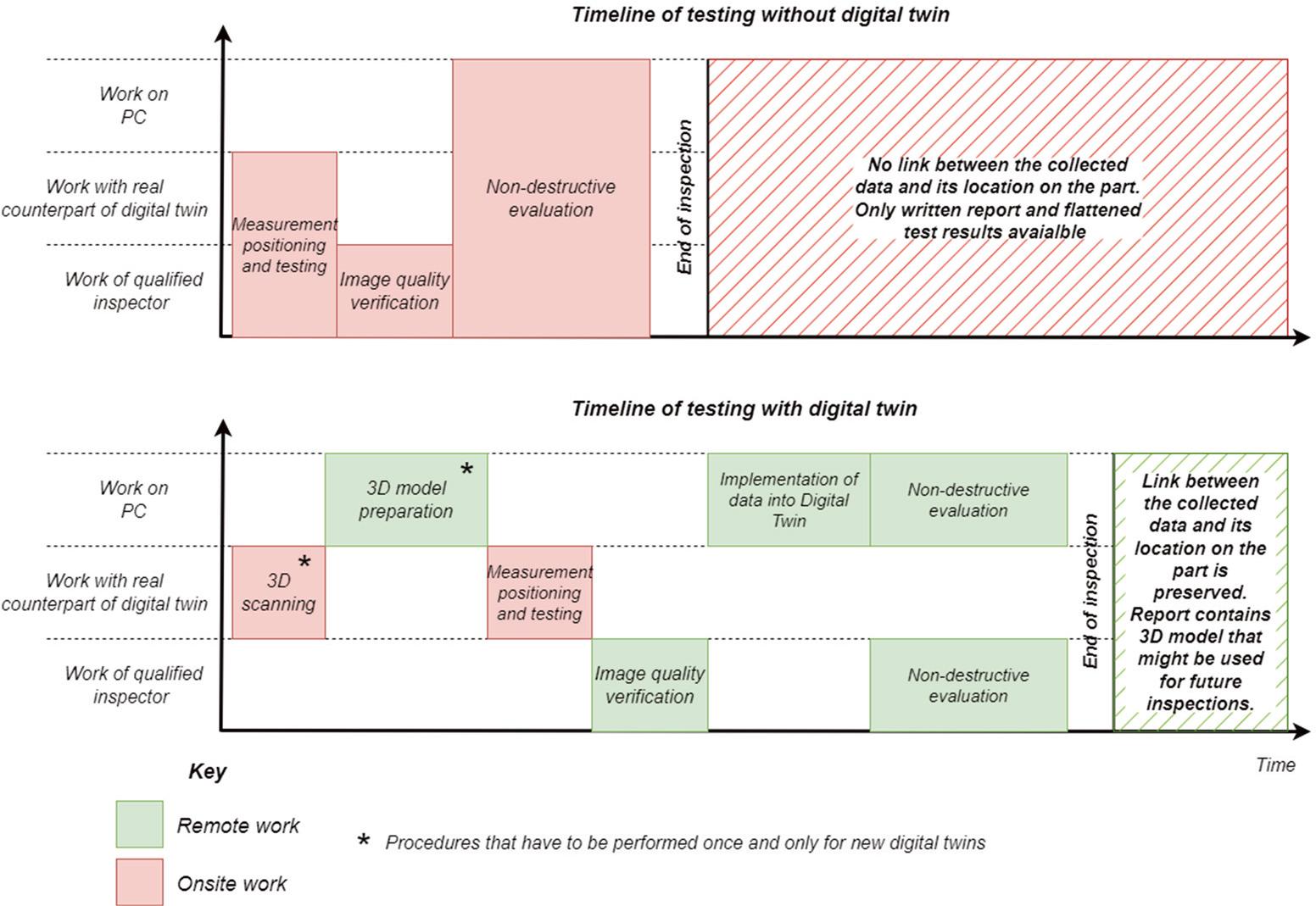

Additionally, a timeline graph illustrating the sequence of actions over time, combined with information about the required assistance or equipment, was prepared and is presented in Figure 5.

Timeline graphs comparing the time needed to prepare an inspection report.

The graphs clearly indicate that implementing a digital twin is initially more timeconsuming. However, as shown, the use of digitalization significantly reduces the need for onsite work. As a result, inspection costs may decrease since qualified inspectors would not need to travel to the testing location. Furthermore, the connection between the test data and the physical part itself is preserved within the software, meaning that physical access to the part is required only during scanning and data collection. Importantly, this data link remains available even after the inspection is completed, allowing the results to be reviewed later on the 3D model if needed. It should also be noted that the extended reporting time occurs only when a digital twin of the part does not already exist. For components that already have a digital representation, the overall testing time is reduced, as 3D scanning and model preparation can be omitted in such cases.

In order to present the inspection data without distortion, the results obtained during testing must be mapped onto a 3D model of the examined item. If a manufacturing-quality model is available, no additional steps are required beyond positioning and mapping the image to display the data in 3D. However, when working with the digital transformation of older projects, one may find that 3D models are often unavailable, as many of these projects were originally designed using 2D drawings.

3D scanning of a part is also necessary when access to the original manufacturing model is restricted due to company policies. In both situations, high-fidelity 3D scanners are required to measure and record the object’s physical dimensions and features accurately. Once the geometrical data has been collected, the process of reverse engineering begins. The scanned files are imported into CAD software, where they can be viewed either as a point cloud (depth files) or as a set of polygons forming a solid or surface model (e.g., STL files).

The time required for post-processing depends on the file format exported from the scanner software, as well as on the capabilities of the software used for further processing. Different solutions are available depending on the platform, and Siemens NX provides a dedicated Polygon Modelling environment with a set of specialized functions for scan refinement and model preparation.

For the case study presented in this paper, the scanner used was MetraSCAN 3D, an optical coordinate measuring machine (CMM) compliant with the ISO 17025 industry standard (Creaform, n.d.). The models obtained using this scanner are characterized by an accuracy of 0.025 mm and a volumetric accuracy of 0.064 mm. The device employs an optical triangulation method combined with advanced image processing technology to capture the precise geometry of the scanned object.

As mentioned in the Introduction section, only NDT methods that provide collected data in the form of images can be used for the digital twin proposed in this paper. These methods include UT and TT.

For the purposes of this study, active thermography was used to obtain the data for projection. There are several off-the-shelf systems compliant with industry standards for TT inspections. The thermography equipment used to collect the data images for the case study in this paper was developed by Thermal Wave Imaging. Their system, called EchoTerm® and shown in Figure 6, consists of a main station with an integrated computer, 2.5 kJ xenon lamps, and MOSAIQ 4.0 software used to configure test parameters and display results. Since the system itself does not include an IR camera, it is paired with the compatible SC7000 IR camera manufactured by FLIR. The complete setup is capable of collecting thermal data with high accuracy and at acquisition frequencies of up to 380 Hz. The noise level of the system is below 20 mK, and the temperature calibration range spans from -20°C to 300°C.

EchoTerm® Thermal Wave Imaging system used to collect TT data images.

The resulting data images can represent the surface temperature as well as its first and second derivatives over time. To minimize potential distortion of the results caused by external heat sources, both the xenon lamps and the IR camera are enclosed within a dedicated housing. Additionally, the enclosure ensures a constant distance between the camera and the test surface, allowing the exact dimensions of the inspected area (230 × 184 mm) to be maintained.

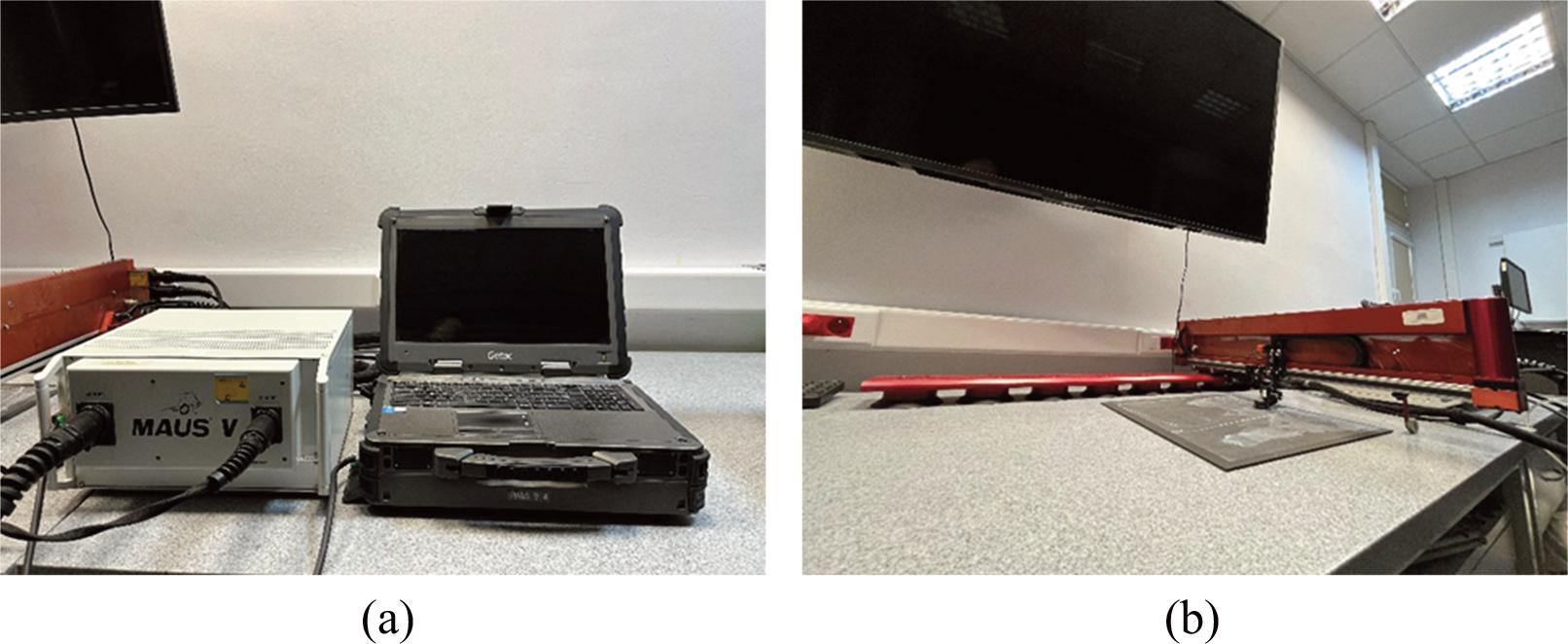

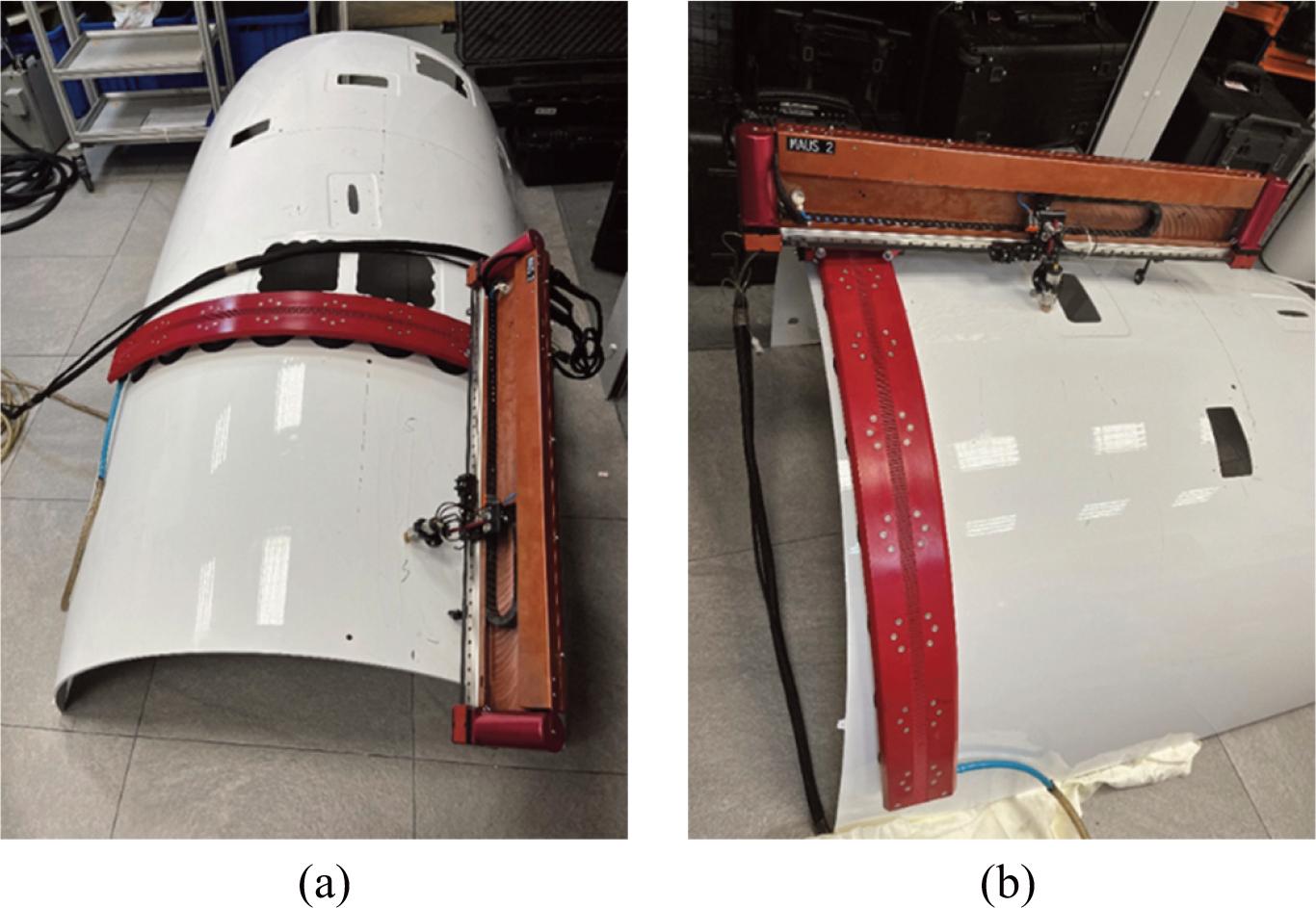

To project UT data onto the 3D model, C-scans must be collected. For that reason, the Mobile Automated Ultrasonic Scanner V (MAUS V), presented in Figure 7, equipped with a Mechanical Impedance Analysis (MIA) probe, was used. The system was designed by Boeing for the USAF to accelerate the inspection of airframe structures using ultrasonic testing (UT). It is capable of generating C-scans of large areas at scan speeds of around 40 m2/h (Palmer & Wood, 1999). The system includes a PC workstation, a set of interchangeable sensors for bond testing, flexible tracks that allow mounting on curved surfaces, and a trolley with an articulated scanning arm. Additionally, a vacuum pump is used to provide stable mounting of the flexible track to the tested surface. The size of the scanned area, the scanning resolution, and the scanning speed can be set in the dedicated software provided with the system.

Components of MAUS V system. PC (a) and track with trolley, arm and sensor (b).

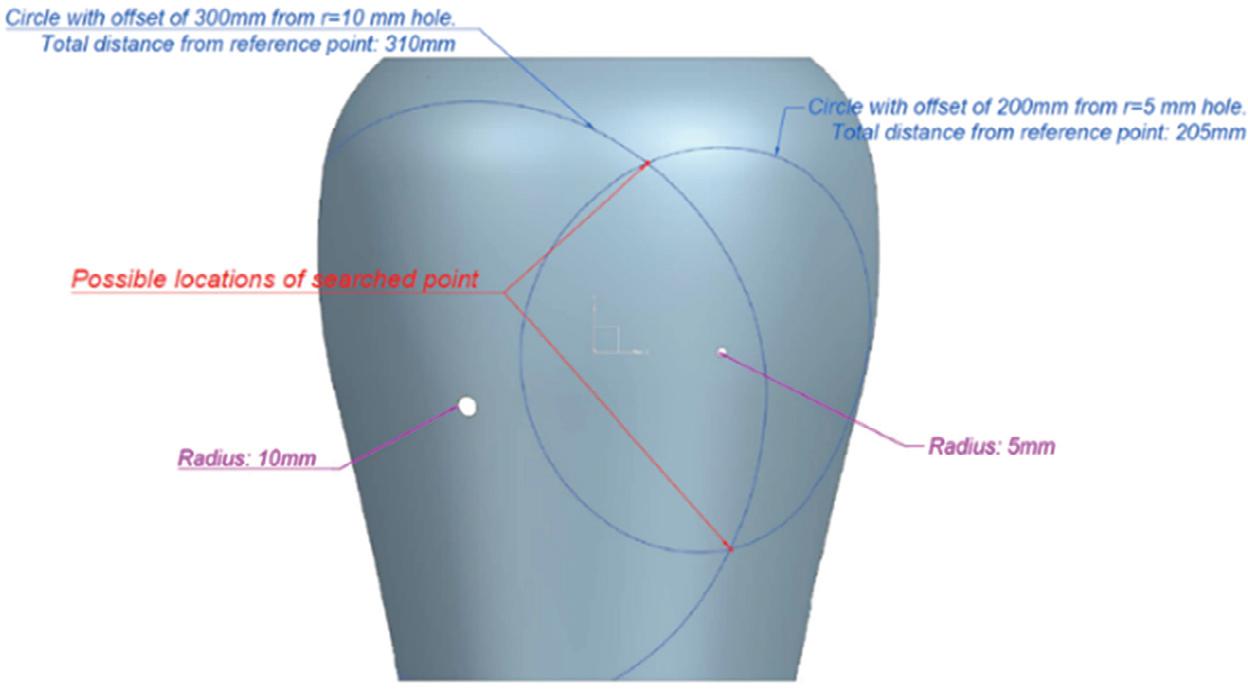

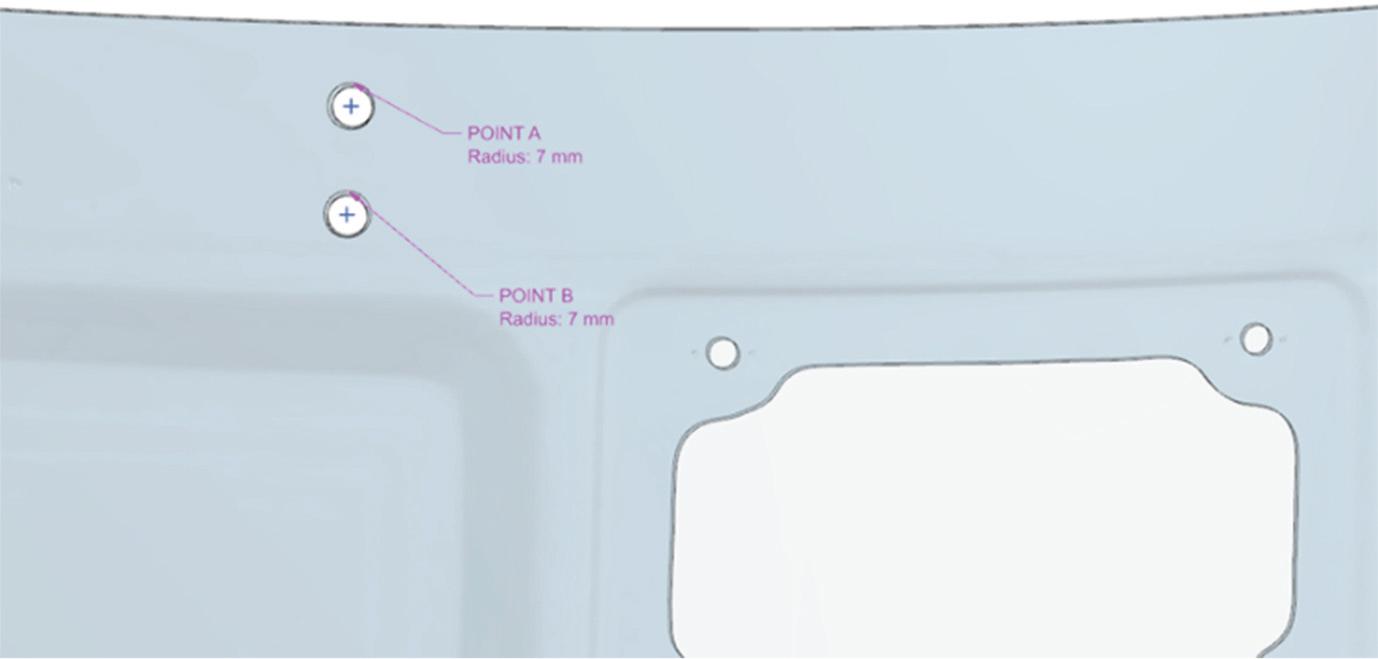

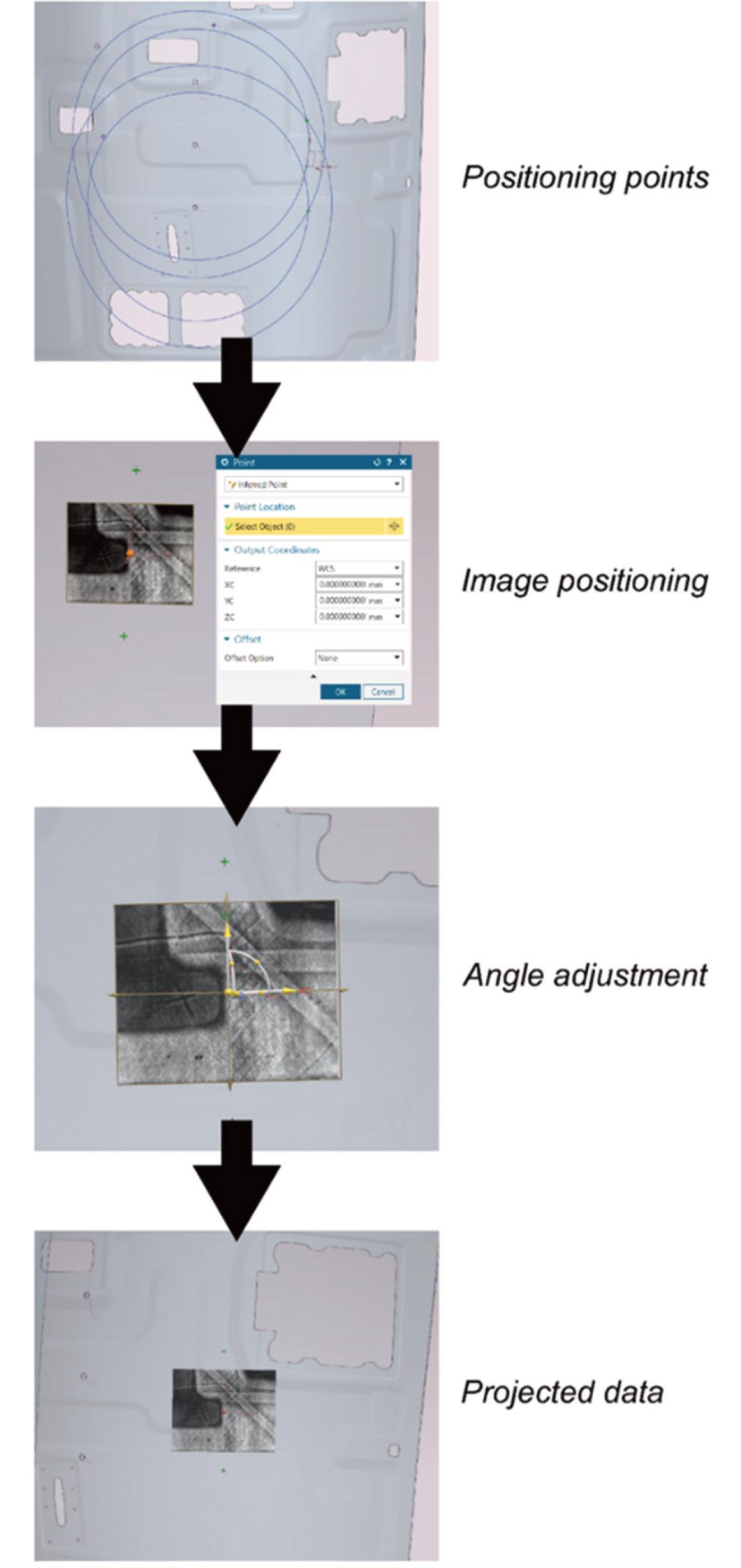

To establish a link between the tested area and the digital twin, it is necessary to accurately position the data image on the 3D digital model. For this purpose, a set of reference points can be defined both on the 3D model and on its real-world counterpart. Ideally, the locations of these points are determined and incorporated into the part during its design stage; however, many existing parts lack such predefined markers. For older components or parts designed without consideration for digital transformation, natural features of the geometry can be used instead. For example, center points of holes or other distinct structural features may serve as reference points. Once it is known that these reference points coincide on both the digital twin and the real part, the position of any point on the part’s surface can be determined.

The only required measurements are the surface distances between the two selected reference points and the point of interest. Using these measurements, the corresponding point can be located on the 3D model by calculating the intersection of two circles drawn on the model surface. Each circle has a radius equal to the measured distance and is centered on one of the reference points. An example of this localization procedure is illustrated in Figure 8.

Demonstration of the point-finding procedure. Reference points are aligned with the center points of the holes. In this example, the searched point is located 310 mm from the left reference point and 205 mm from the right reference point.

Since UT collects data images over the surface, whereas TT acquires images through projection, different image mapping methods are required for these two cases. Mapping images obtained from UT testing requires the introduction of a UV map on the part’s surface. This functionality is available in the NX Studio application. By using UV mapping, the surface of a 3D object can be “unwrapped” into a corresponding 2D image. The data images obtained from UT can then be mapped onto this 2D surface representation and subsequently “wrapped” back to reconstruct the 3D geometry.

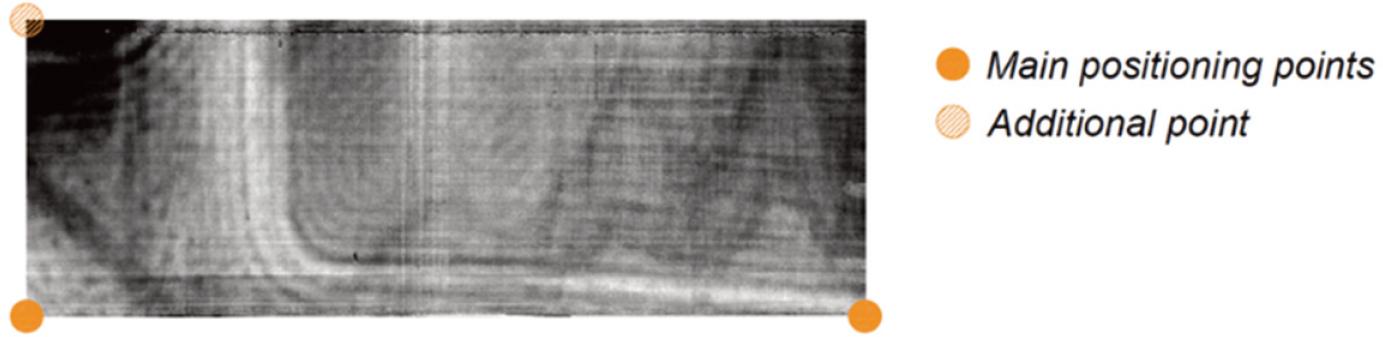

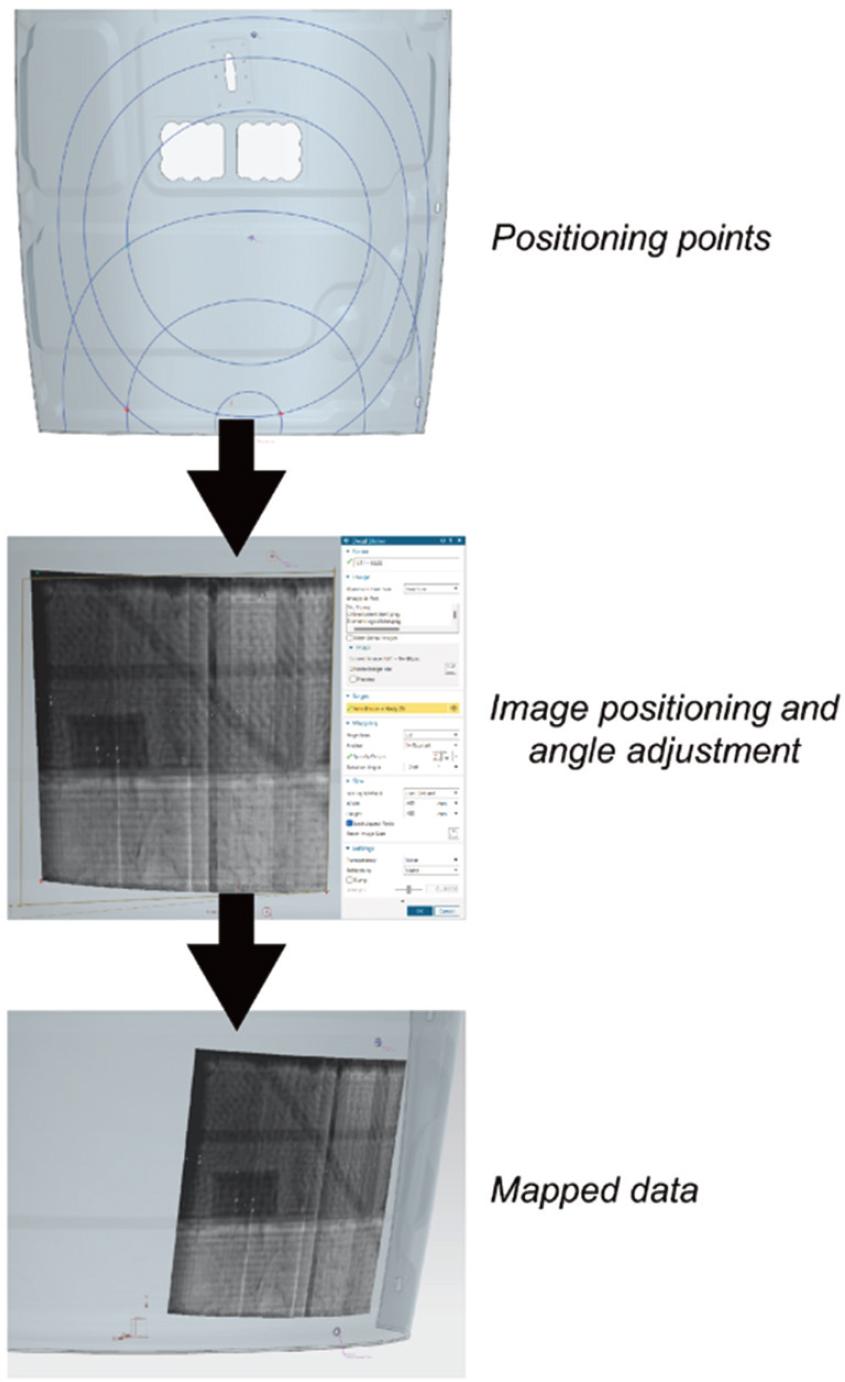

To correctly position and align UT data images on the model, three points must be defined on the part’s surface. Two of these points are used to establish the correct position and orientation of the image, while the third point serves to verify the accuracy of the mapping. These points should be placed at the corners of the data image, as demonstrated in Figure 9.

Points that must be localized on both the 3D digital model and its real counterpart to correctly position UT data on the model.

In the case of images obtained using a camera, a planar projection should be applied to map the data onto the 3D model. This projection method involves projecting the image onto a plane and then onto the object’s surface. In this way, the image acquisition process can be simulated with sufficient accuracy, particularly for small images. To ensure proper data collection, all images should be captured from the same distance relative to the part’s surface; otherwise, the real image dimensions would be unknown. Additionally, the inspection should be performed perpendicularly to the tested surface to avoid introducing geometric distortions into the resulting images.

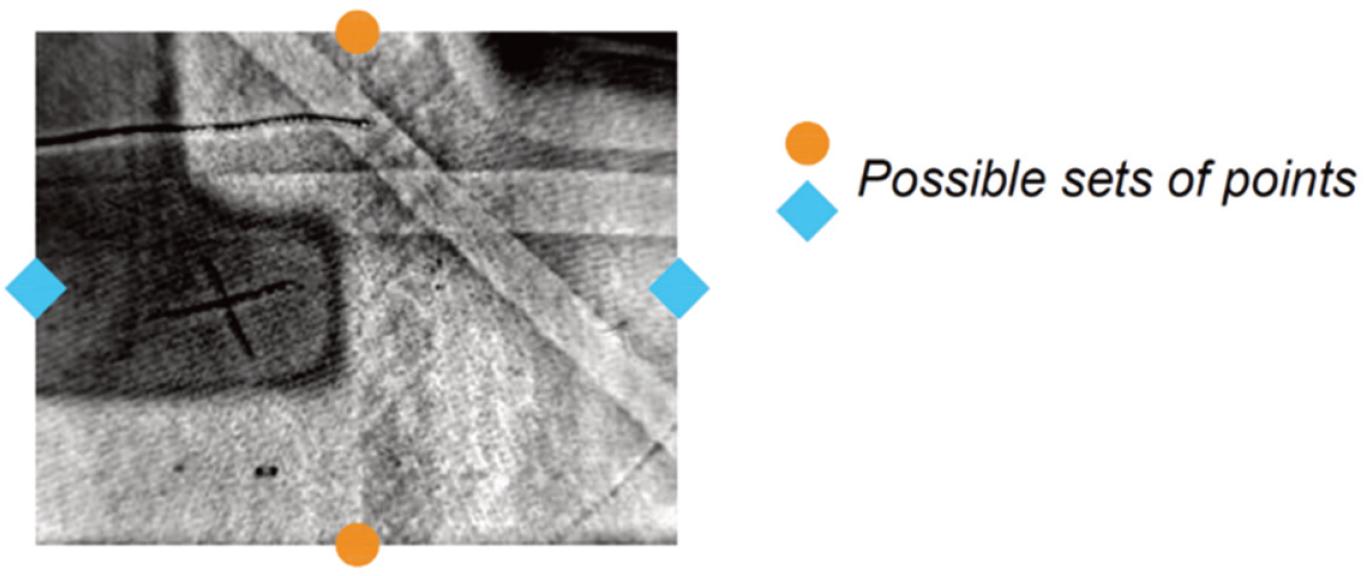

To correctly localize the image on the 3D model, two points must be defined on the part’s surface. These points should be positioned at the midpoints of a selected pair of opposite image edges, as illustrated in Figure 10. Since the planar projection function in NX accepts only a single point as input, the two points are used to determine the image orientation and to calculate the central point, which then serves as the origin of the projection. Furthermore, the image must be projected from a plane that is tangent to the part’s surface at the central point. To achieve this, an auxiliary data plane tangent to the projection surface at the central point should be created, along with a new coordinate system. The Work Coordinate System (WCS) should then be set to this newly defined Datum Coordinate System.

Possible sets of points that must be localized on both the 3D CAD model and its real counterpart to correctly position TT data on the model.

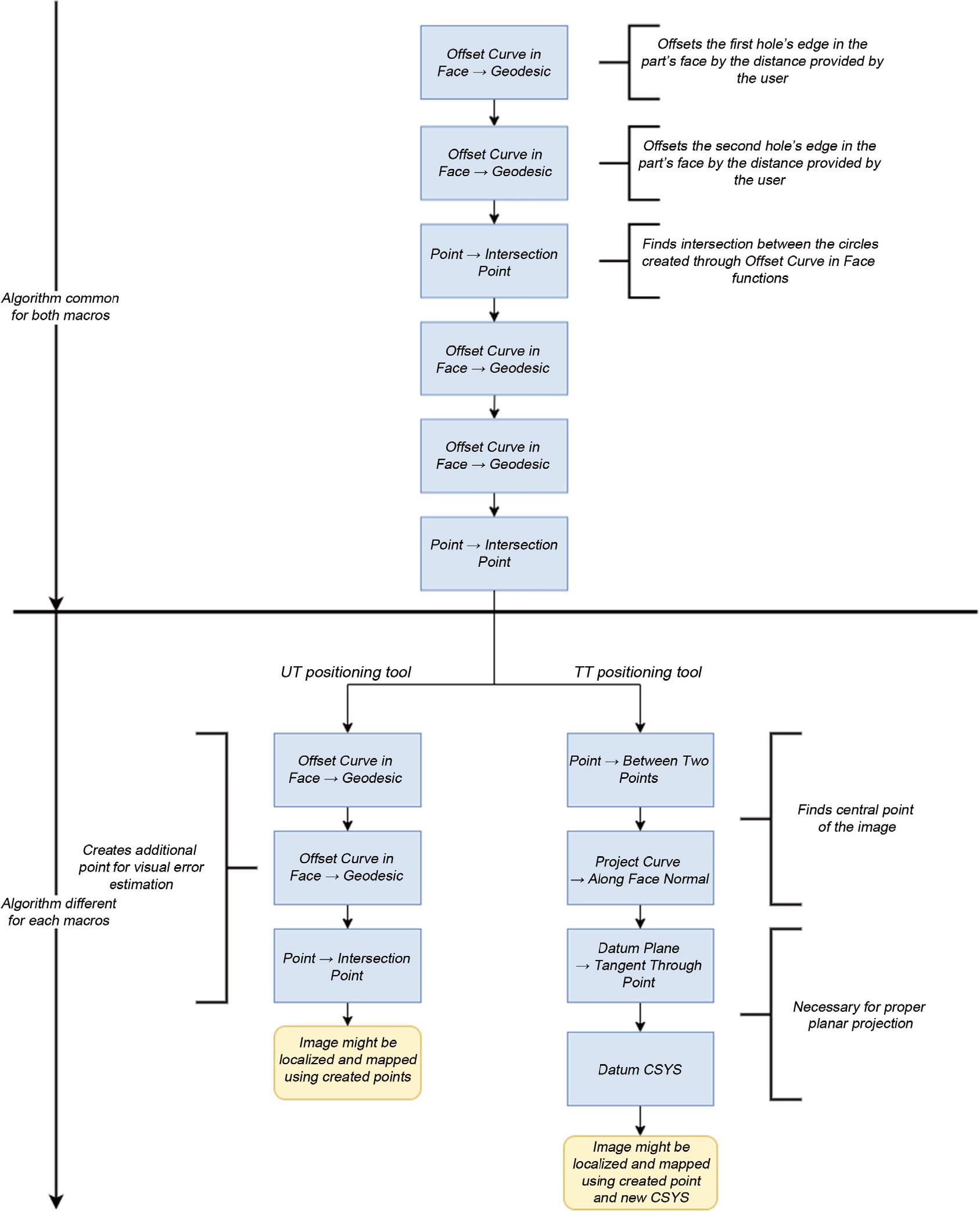

A summary of the number of reference points required for each projection type, as well as the sequence of actions that need to be performed, is presented in Figure 11.

Flow chart presenting the actions that must be performed during inspection.

In order to speed up the process of locating reference points on the surface of the 3D digital model, macro files were created to automate parts of the workflow. The sequences of operations contained in these macro files are presented in Figure 12.

Macros developed to properly position data images.

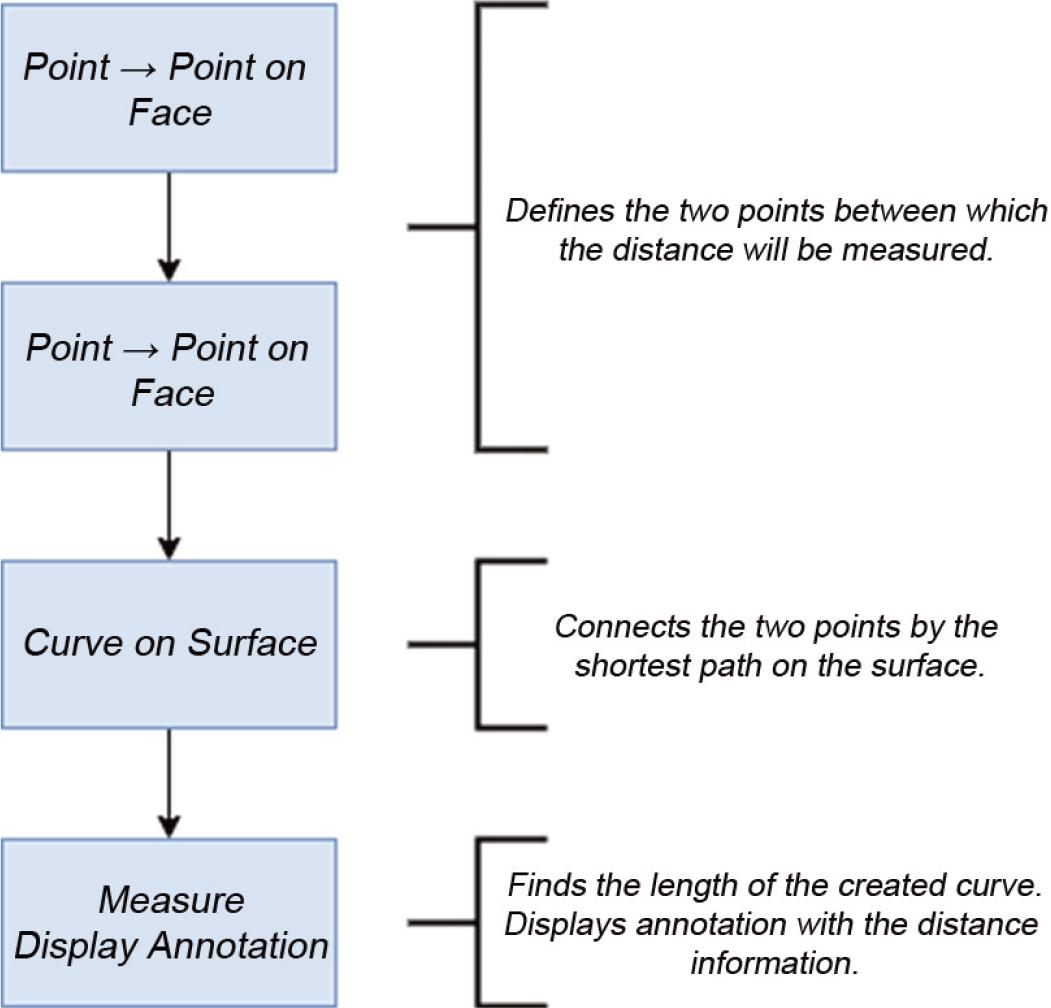

To enable the remote evaluation of NDT results, inspectors must be able to accurately assess both the size and orientation of any defects detected on the part. For this purpose, an additional macro was developed to facilitate measurements directly on the surface of the 3D model. The flow chart illustrating the sequence of Siemens NX functions used in this macro is presented in Figure 13.

Macro developed for measurements on the model.

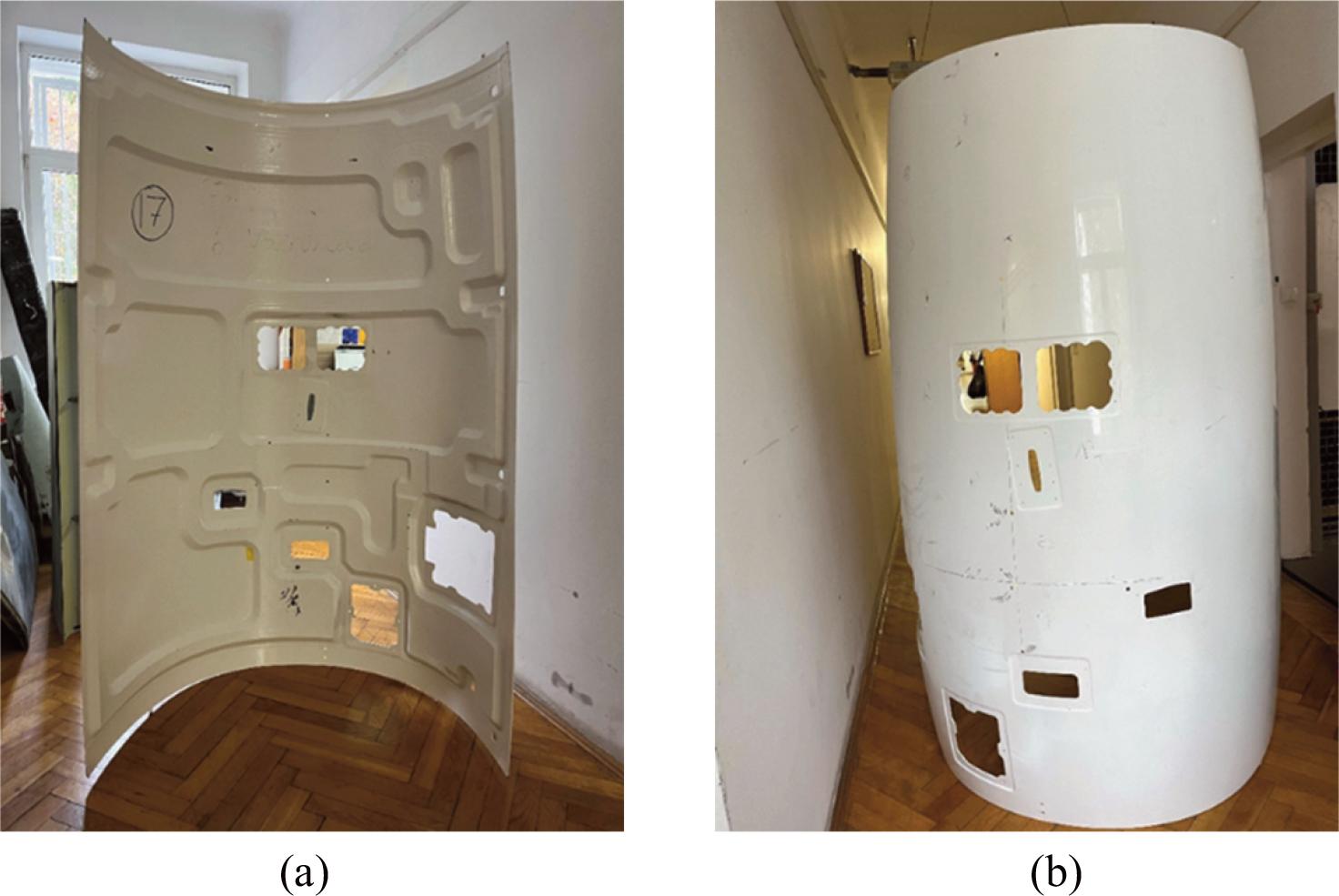

The part selected for the case study, demonstrating the process of implementing a digital twin for NDT results visualization and 3D data storage, was the bottom section of the nacelle used in Honeywell HTF7000 series turbofan engines. The location of the part on the engine is shown in Figure 14. The HTF7000 engine is used on several types of aircraft, including the Bombardier Challenger 300, Gulfstream G280, and Cessna Citation Longitude (PZL Świdnik, n.d.). The nacelle component is made of composite material, reinforced with a honeycomb core in structurally vulnerable areas. The tested specimen had multiple areas of internal damage on its inner side as a result of previously conducted tests. The part is presented in Figure 15.

Honeywell HTF7000 nacelle. The contour of the tested part is marked with a red line. Original image source: Safran Group (2021).

Inner (a) and outer (b) side of the specimen.

The file containing the geometry measurements was exported from the 3D scanner software as an STL file without any initial post-processing. To obtain a usable 3D model, all necessary corrections and refinements were performed using Siemens NX. Since operations carried out within the Polygon Modeling Task Environment are irreversible once the environment is closed, it was essential to plan the workflow carefully and create backup files after each type of defect was fixed.

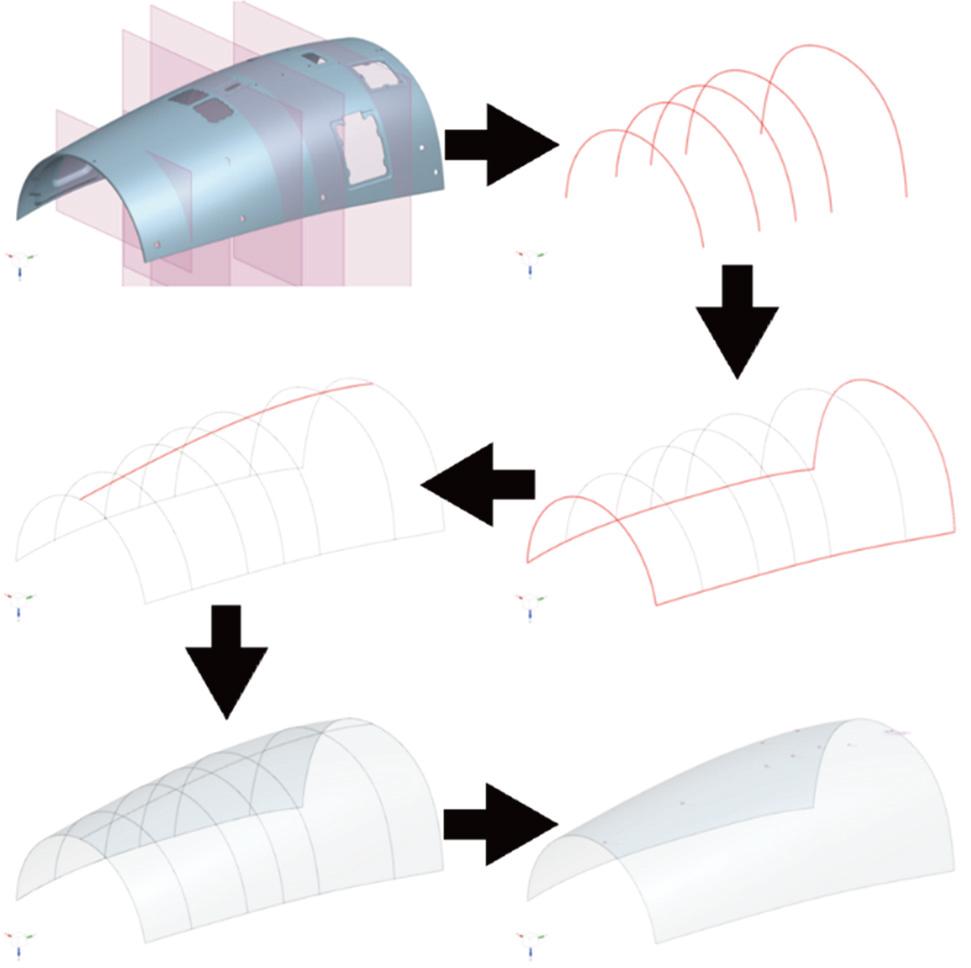

The scan was post-processed to meet the software requirements: the model had to be defined as a solid body, feature sharp edges, and have all scanning artifacts removed. At this stage, the software already allowed for projecting images directly onto the body’s surfaces. However, to enable the creation of a UV map, an additional continuous surface was required, since the existing surfaces were polygon-based and therefore discontinuous. To generate this surface for UV mapping, the post-processed model was sectioned, and the resulting curves were then used to define a new continuous surface suitable for accurate texture mapping. A graphical representation of this process is shown in Figure 16.

The process of creating a surface for UV mapping and image localization.

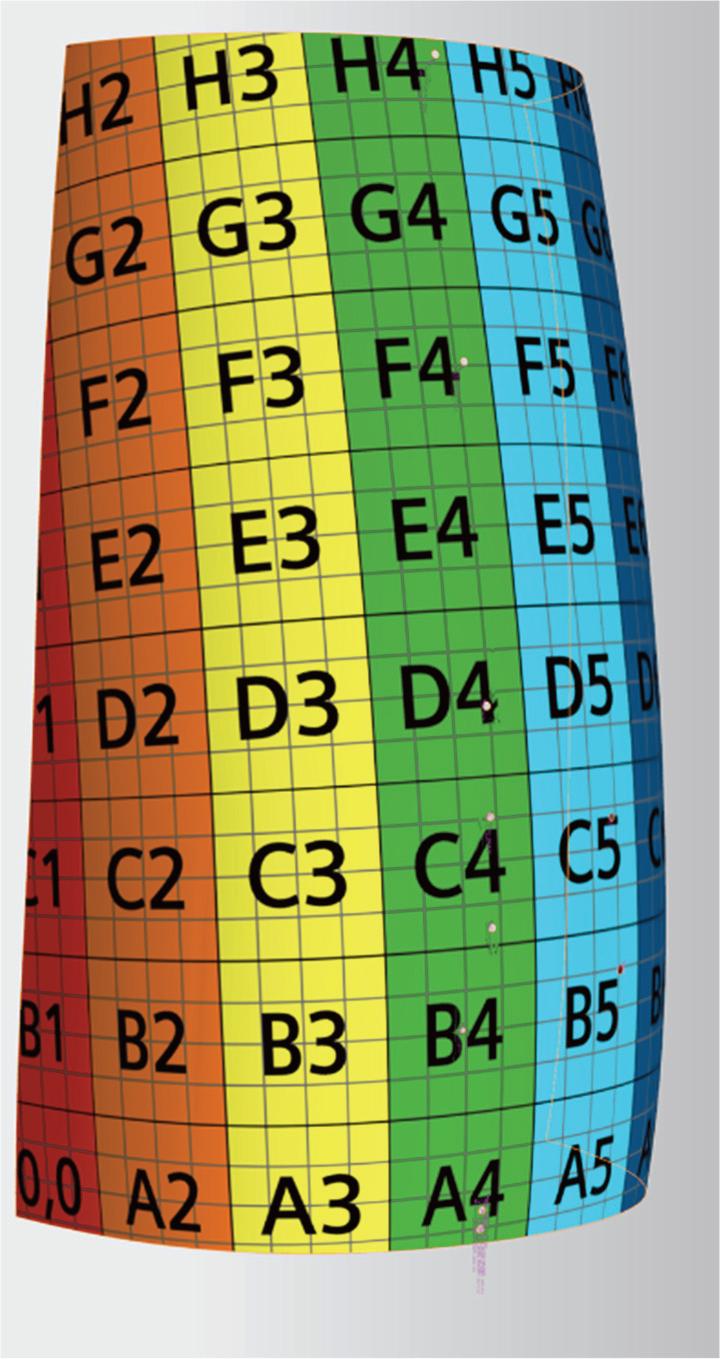

The surface so obtained was then used to define a uniform UV map within the NX Studio environment. The resulting final UV map is shown in Figure 17.

UV map created on surface created for result-mapping and projection.

The final form of the model ready for mapping is presented in Figure 18.

Model after post-processing.

The reference holes, which contain the measurement reference points, are annotated with information about their radius and assigned a unique letter. Each hole is labeled with a different letter to minimize the risk of errors when importing the image into the model. An example of these annotations is shown in Figure 19.

Example of annotations on reference holes.

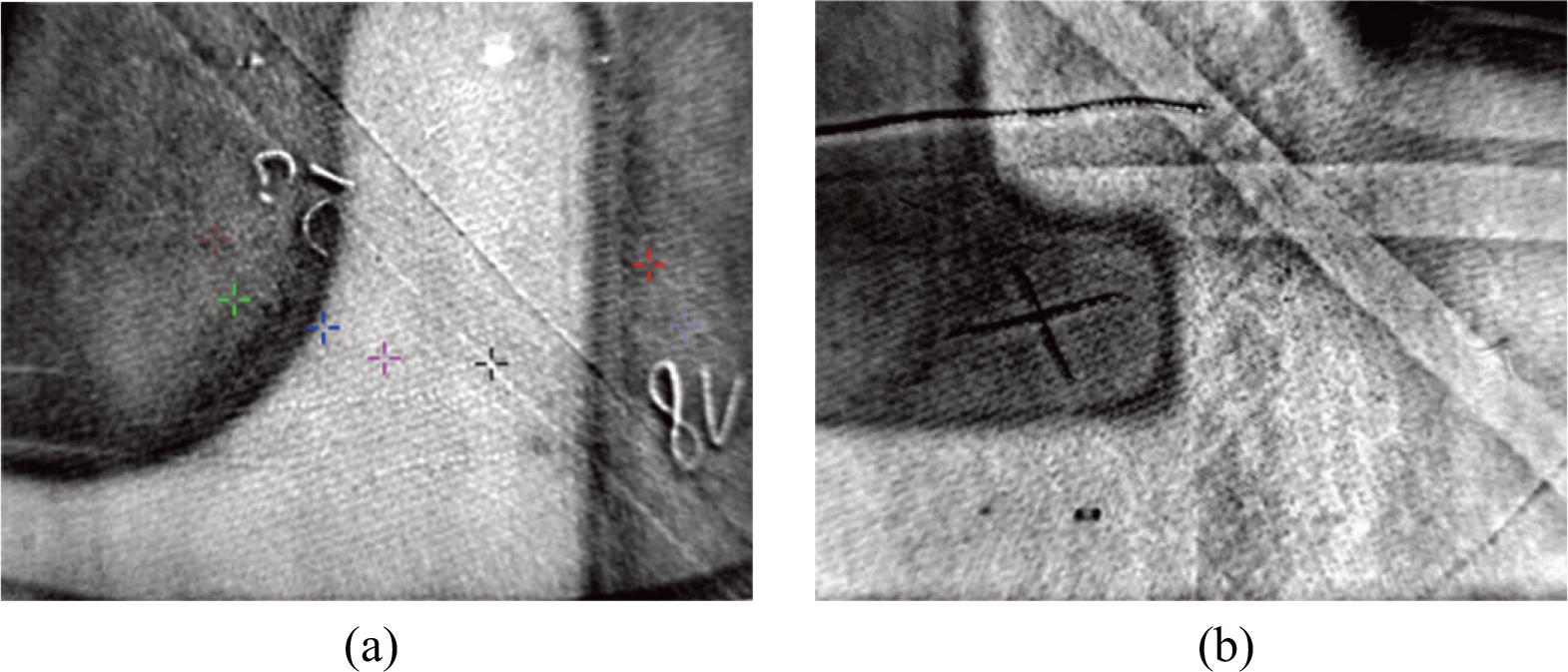

With the digital model prepared for 3D results visualization, data from the real component could be collected. In the case study, two NDT methods were used to obtain images for projection. The collected data images are shown in Figure 20.

TT results for the tested areas near the points (a) E and H – ID:TT1; (b) H and I – ID:TT2

The next two images were collected using the MAUS V system equipped with a bond testing (MIA) sensor. These measurements were performed over a larger surface area to evaluate whether the proposed mapping method could also be applied in such cases. The first test was performed in the area near the B and C reference holes (ID:UT1). The second test was conducted between the J and K reference holes (ID:UT2). Photographs of the testing process and the corresponding UT data images obtained during inspection are presented in Figures 21, 22, and 23.

Photographs of UT testing in progress. Test IDs: UT1 (a), UT2 (b).

UT results for tested area near the points J and K. Image represents the C-scan. ID:UT1.

UT results for tested area near the points B and C. Image represents the C-scan. ID:UT2.

The NX – Studio environment was used to perform the image processing. The procedure for localizing and projecting the TT image is presented graphically in Figure 24.

Steps of TT image projection onto the model. Positioning points were obtained using macro. Example of TT2 projection.

To compare how the procedure for UT image mapping differs from the one used for TT image projection, the instructions for UT mapping are shown graphically in Figure 25.

Steps in UT image mapping onto the model. Positioning points were obtained using macro. Example of UT1 mapping.

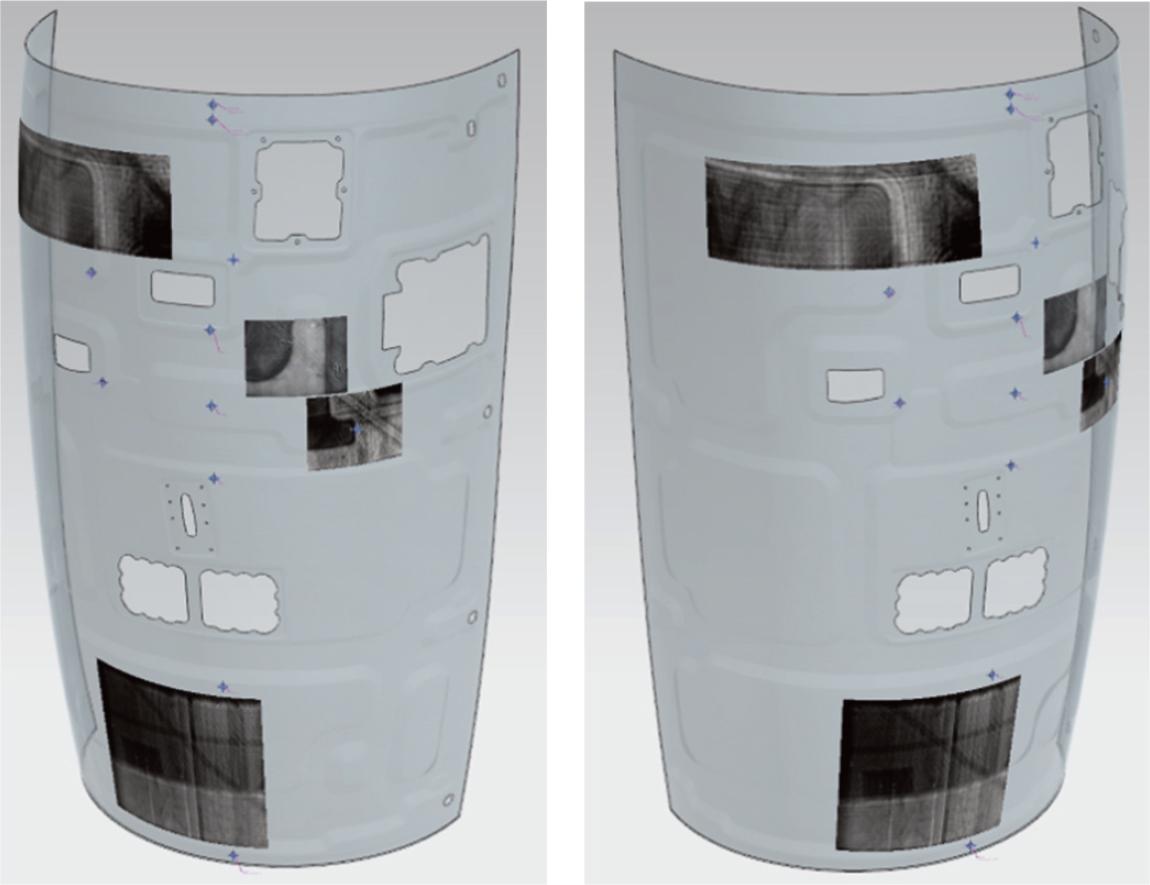

The final version of the digital twin, prepared for the purposes of this case study, incorporates all four data images presented in the previous section and is shown in Figure 26.

Digital twin with mapped/projected inspection results.

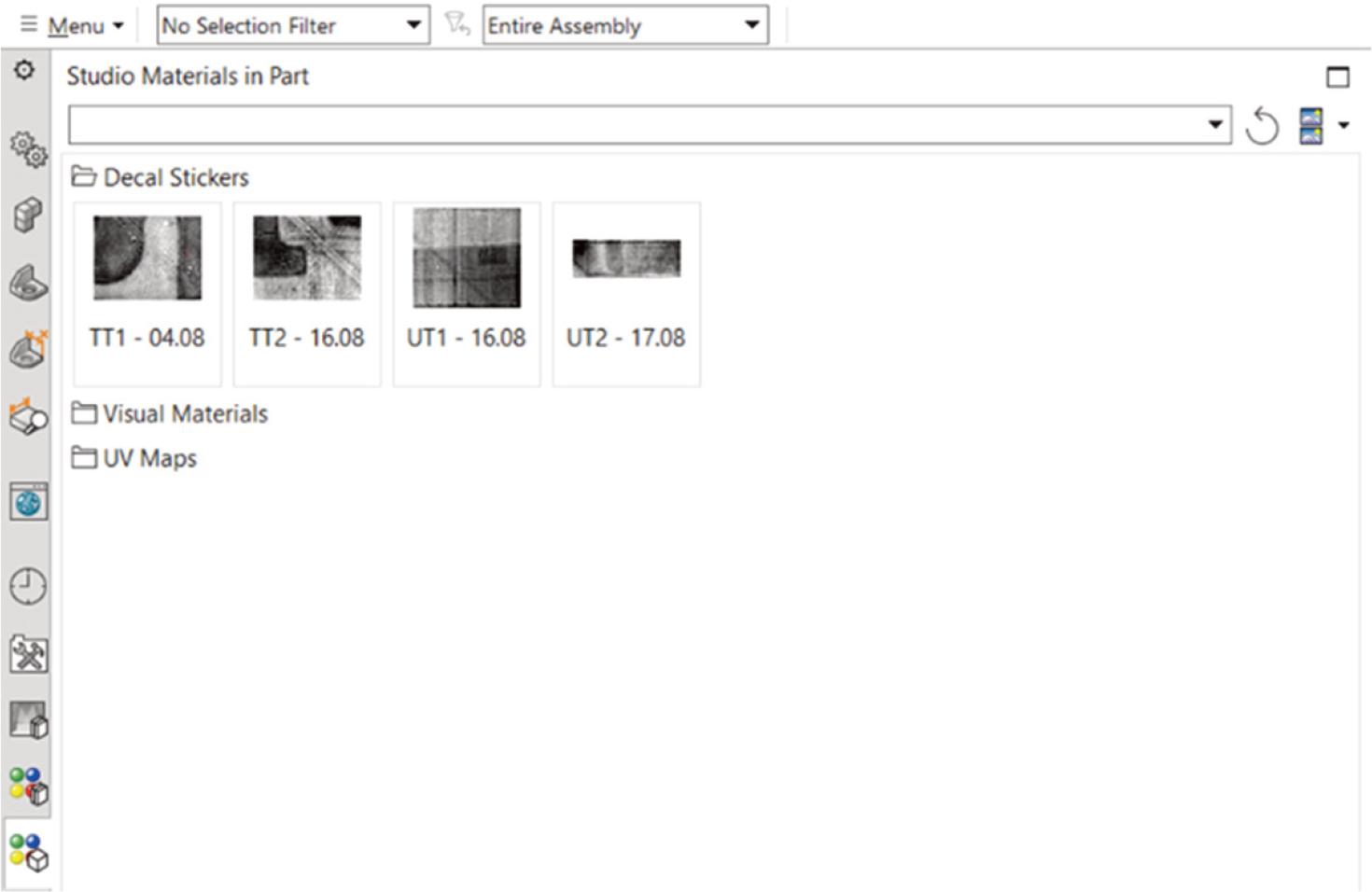

One of the key aspects of the digital twin developed in this case study is its ability to present, store, and organize image data effectively. Since all data images are implemented into the model in the form of decal stickers, the most straightforward and convenient way to manage these files is through the Decal Stickers folder, located within the Studio Materials section of the Part Palette.

All images projected or mapped onto the model are automatically stored in this palette by default. Each sticker can be renamed, allowing for the use of consistent naming schemes. Additionally, the files in the folder are arranged in alphabetical order, making it easier to locate a specific image among many others.

Users can also customize the way images are displayed within the folder by choosing one of four available viewing modes: list, icons, tiles, or thumbnails. An example of the folder containing the data images used in this case study is shown in Figure 27.

Decal Sticker folder containing mapped/projected images presented in the form of thumbnails.

This study has investigated the feasibility of creating a digital twin capable of storing and presenting inspection data in a 3D environment. The proposed solution also allows the software to be used for implementing design changes when required, potentially extending the lifespan of a part. Although the presented case study focused on data images obtained through UT and TT inspections, the proposed workflow is applicable to any type of NDT method in which data images are acquired either through projection or over-the-surface scanning.

The implementation of digital twins represents a relatively new concept that is attracting significant attention, particularly in the context of Product Lifecycle Management (PLM). The ability to store historical inspection data while simultaneously enabling designers to introduce design modifications creates a cause-and-effect framework for continuous product improvement. As a result, components can be adapted and optimized throughout their lifespan, ensuring that their design remains up-to-date.

The creation of digital twins in the form presented in this paper not only offers a valuable tool for PLM but also significantly enhances the visualization of NDT results. A three-dimensional representation of inspection data enables inspectors to determine defect size and precisely locate damage with improved accuracy. Furthermore, once the data is projected or mapped onto the digital model, its spatial position is stored permanently within the digital twin. This eliminates the need for physical markings on the part and removes the necessity of searching for previously tested areas, as all relevant information can be accessed directly through the digital twin.

Digital twins implemented in the form presented in this paper could also be of significant interest to aircraft operators. Databases that integrate the capability to display inspection results directly on the part model can serve as powerful tools for fleet management. Both civil and military operators could monitor the condition of components more effectively and potentially predict and plan maintenance in advance, using data stored in the digital twin database. Moreover, the effectiveness of any repairs could be easily tracked, allowing operators to develop optimized maintenance practices based on actual inspection history. Additionally, the use of digital twins could reduce maintenance costs, as certain steps of the inspection process could be performed remotely by qualified personnel. Tasks requiring physical interaction with the part could be carried out by on-site mechanics, while inspectors would only need to evaluate the collected data remotely through a digital file containing the model with the projected or mapped test results.

The digital twin of the nacelle developed in this case study demonstrates all of the advantages mentioned above. Since it was created in CAD software, any modifications to the model are easy to implement, track, and manage. Combined with the measurement macro, the nacelle’s digital twin supports remote sizing and evaluation of detected defects. Furthermore, because Siemens NX stores image files directly within the CAD environment by default, there is no need for external software to manage the NDT results database. Multiple data images can be displayed on the model simultaneously, enabling inspectors to track the evolution of damage over time and identify recurring defect patterns in the structure.

Unfortunately, since a single file is used to store all data – including both the geometry and the inspection images – the resulting files can become quite large. As a consequence, the system requirements needed to run the software smoothly are relatively high. For this reason, it may be worth considering the creation of a lightweight version of the digital twin model. In such an approach, the complete file containing all data would be stored on a dedicated workstation or server, while the files sent for inspection would include only the specific data subsets necessary for evaluation. This would reduce processing demands on local machines while maintaining access to the full database when required.

One of the most important future improvements that could be made to the proposed scheme is its automation. Developing software tools that assist engineers by streamlining and accelerating the process of implementing inspection data into the digital model is crucial for ensuring the industrial viability of the solution presented in this paper. While developing such tools, particular attention should also be given to accuracy. Based on observations from the developed digital twin, the combination of positioning, mapping, and projection methods provides satisfactory accuracy. However, to determine the magnitude of potential errors in positioning and data projection, further accuracy testing using precision measuring tools should be conducted.

Another key objective of the scheme is to enable remote evaluation of inspection results. To minimize the differences between on-site and remote inspections, the integration of Virtual Reality (VR) technology could play a significant role. Inspectors working remotely would be able to interact with a 1:1 scale digital representation of the real component. This increased level of immersion could enhance their ability to analyze test results as if they were working directly with the physical part. Since Siemens NX already includes a dedicated VR visualization environment, the concept of maintaining all data within a single software platform remains applicable while simultaneously supporting the development of more advanced visualization techniques.

The goal of the scheme for the development and implementation of digital twins has been achieved. However, as stated in the introductory part of this article, the term digital twin is broad, and therefore there is considerable room for improvement and further development of both the scheme and the exemplary digital twin.

Firstly, only two different NDT methods that produce data images were presented in the case study section of this paper. Images obtained using other methods (e.g., ST, RT) could also be mapped or projected using the existing scheme; however, another case study should be carried out to verify whether any new challenges arise when visualizing the results of these methods on the model.

Finally, it should be noted that the type of digital twin proposed in this paper focuses exclusively on inspection and maintenance data visualization. In future iterations, several new schemes may be introduced to extend the applicability of the digital twin. A more detailed model of the part could be created to accurately represent the materials from which the component is made. Additionally, more advanced tools, such as finite element method (FEM) analysis or damage growth models, could be implemented to support the work of design and maintenance engineers to a greater extent. Ultimately, digital twins representing individual parts could be combined to create an assembly constituting a complete digital twin of the aircraft or one of its major subsystems.