The demonstration of the residual strength of a wing co-bonded stiffened panel with one disbonded stiffener is an important challenge in aircraft certification. Understanding the structural behavior and failure modes over the complete panel design is essential to ensure the required robustness of such panels. Although composite structures offer excellent strength-to-weight ratios, their failure mechanisms are complex, particularly for the complex local loadings that occur during buckling and post-buckling. Moreover, wing panel design varies significantly from one zone to another, depending on the constraints to which it is subjected. When loaded in compression, they are generally sized by strength criteria such as filled hole compression, compression after impact, or buckling, whose criticality depends upon the design parameters such as thickness, layup, or stiffener pitch. When debonding a stiffener, the larger skin bay becomes critical in buckling (but not always), so that the panel strength becomes a post-buckling problem where the failure occurs either by the post-buckling of the lateral stiffeners or by their failure due to the pull-out force generated by the buckled skin. In that case, the failure is due to the lateral stiffener disbond initiation and propagation or by unfolding of their flange. A standard approach would be to perform tests on specimens of different complexities that cover the design space in order to account for the different failure modes that may happen in the aircraft structure. The other option is to rely on a numerical model that is able to simulate the panel behavior at different scales, in particular at the wing level to be able to compute the buckling modes and loads, and also at the local level to predict the disbond initiation and subsequent bond failure, as well as the interaction of these two scales. These computations must be made at reasonable costs in order to be used in an industrial context. This numerical method must be validated by a test pyramid that includes coupons that can identify and characterize single damage modes and also more complex and larger specimens that can validate the simulation method on complex loading and account for multiple interacting modes of failures.

For this particular problem, Dassault Aviation has developed an industrial numerical damage model with a “reduced” complexity that is able to predict the delamination and disbond of a co-bonded stiffener, and applicable to a complete wing finite element model. This damage model can be inserted into the model of a large aircraft component that is able to predict the buckling and post-buckling behavior of the structure and locally the initiation of damages and their propagation until failure.

The damage modes are identified at coupon and subcomponent levels and are simulated by introducing nonlinear behavior at interfacial elements located where damages and failures have been observed. This nonlinear behavior consists of a progressive alteration of the mechanical properties using a plastic behavior, the final failure being considered by deleting the broken elements from the stiffness matrix using an energy release rate criterion. The identification of the model parameters for both plasticity and energy release rate criterion are carried out at coupon level and may be corrected at the higher level of the test pyramid to take into account relevant technological parameters. The model is then validated at subcomponent level and applied on a complete wing box to justify the wing box structural strength.

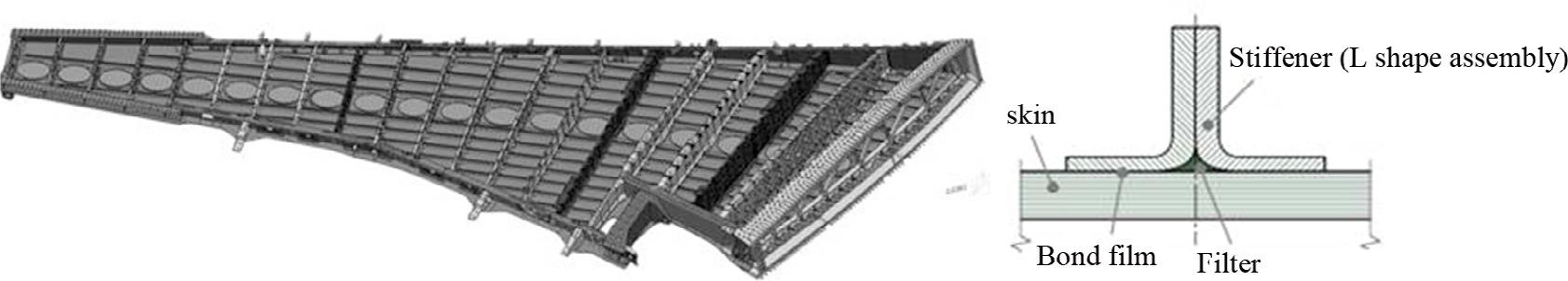

In the example presented in this paper, the composite stiffened panels is made of a pre-cured skin on which stiffeners are co bonded. The stiffeners are composed by two back-to-back L shaped flanges and a filler. Wing ribs are joined to the panel by fasteners.

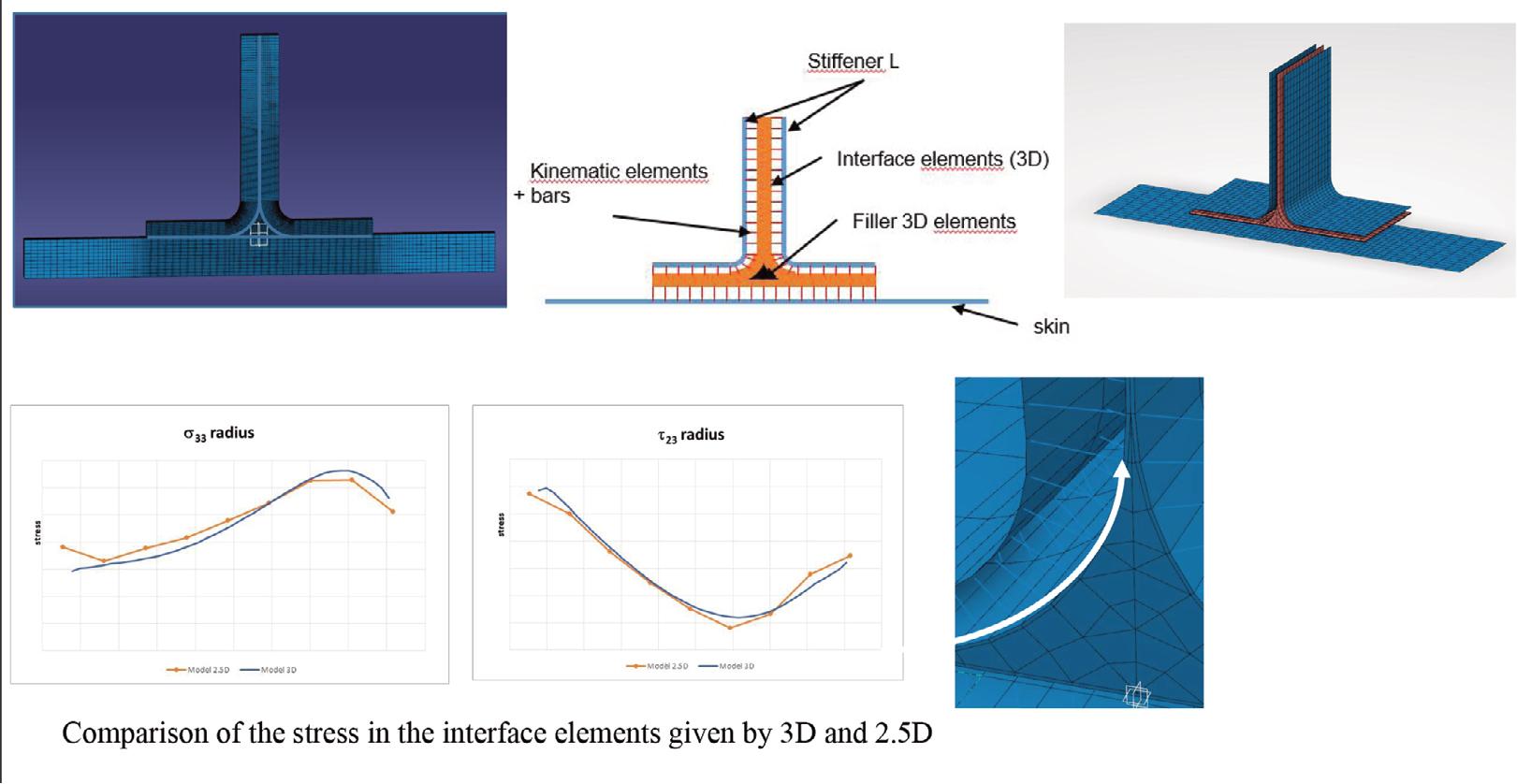

The structure is modelled by classical anisotropic elements with linear elastic behavior except some particular zones where specific interface elements are added where damage and failure can occur. These interfaces represent resin between composite plies or adhesive films, which are supposed to work out of their plane only, their in plane stiffness being negligible compared to the ply stiffness. The behavior of those elements can be represented by the following matrix.

On these elements, the failure is predicted by an energy release rate criterion, while preliminary damages are accounted for by using a plasticity criterion. Considering the particular behavior of interface elements, a simplified Hoffman criterion is used for the plasticity model.

The computation of the energy release rate depends on mode I and II and their mixed mode ratio given by: MR = GIIc/(GIc+GIIc).

These interface elements can be used inside a stacking sequence to simulate internal delamination or between bonded elements to simulate the disbond. They can be associated to 2.5D plate elements or 3D elements.

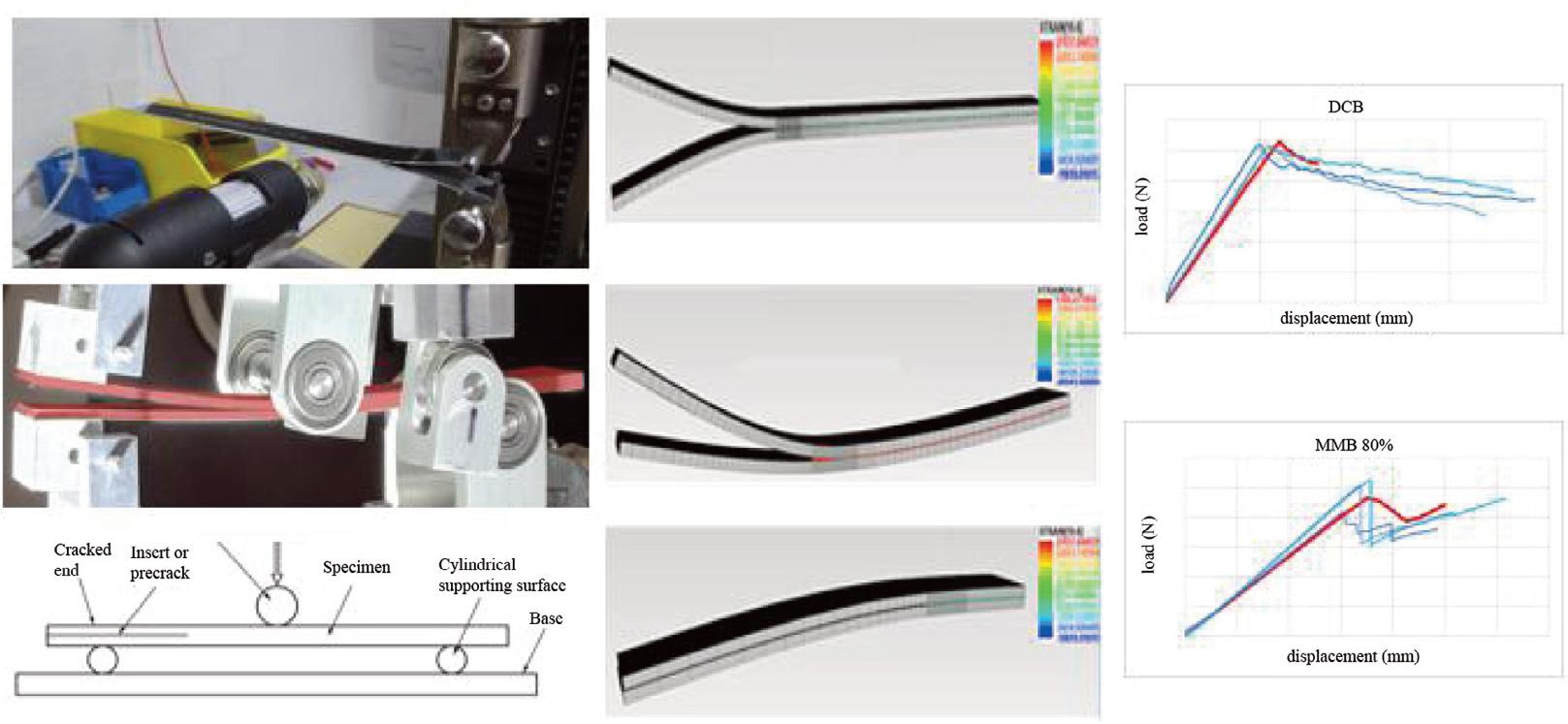

The parameters GIC/GIIC and the mixed mode toughness curve as well as the yield stress are identified using following tests:

Coupons defined by ASTM standard tests procedure.

Coupons representing a flange to skin interface.

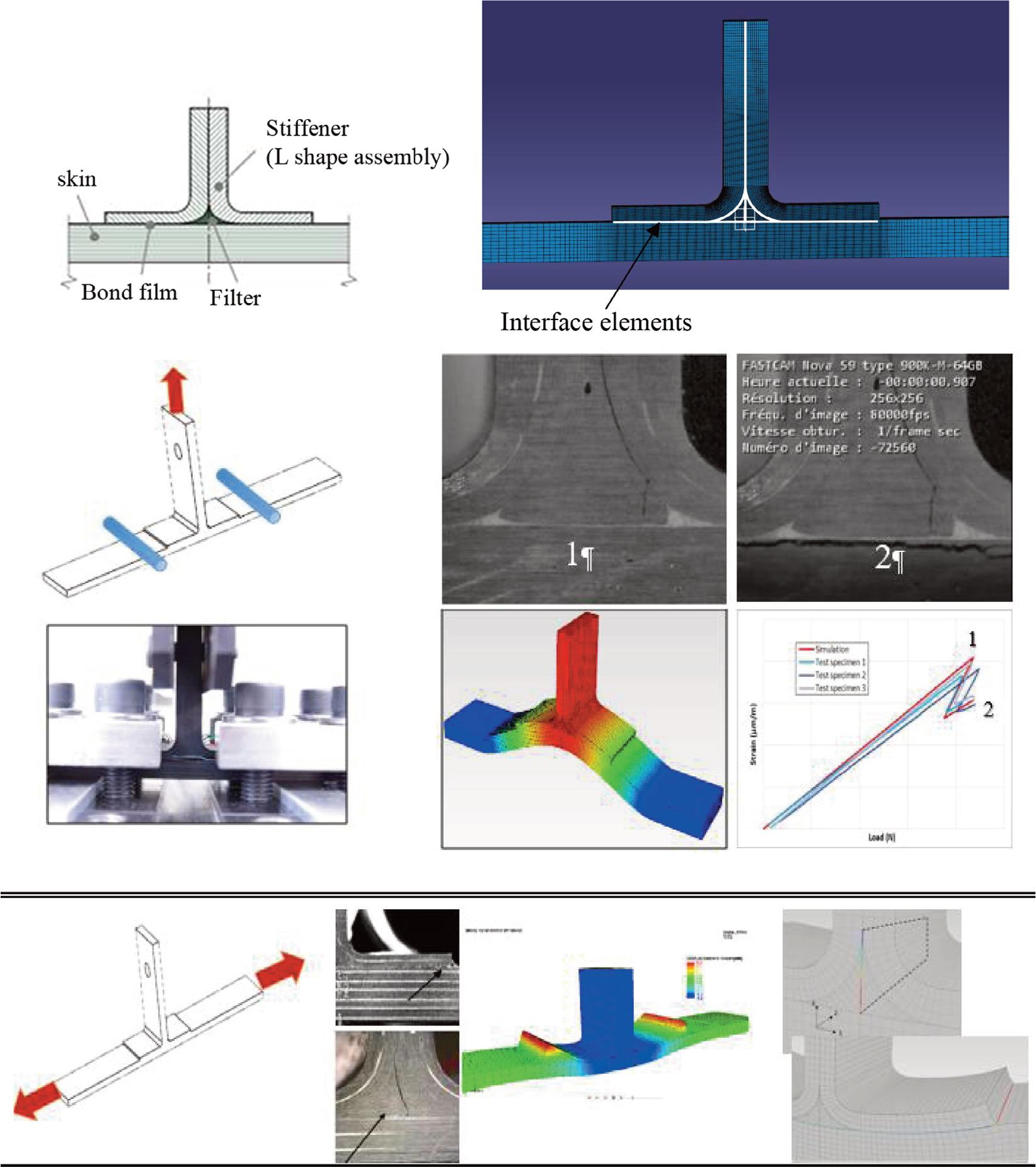

Element tests representative of the stiffener to be justified and its connection to skin panels. These tests are conducted considering different loading conditions. They are instrumented to identify the damage initiation zones and subsequent propagation until failure.

These tests show the different failure modes and their impact on the stiffness of the joint. For example, the transvers tension reveal a failure at the flange extremities (which is anticipated) and also a matrix cracking inside the filler with little effect on the strength. Stiffener pull out tests show that the damage onset is predominantly a failure of the interface between the L and the filler in radius region, this damage grows until it reaches the interface between the skin and the filler then the specimen fail. The behaviour of the specimen after the damage onset depends greatly on the configuration but generally, the load cannot increase much after the damage onset. In some rare situations (short support distance) the damage onset appears inside the filler by matrix cracking. All these observations lead to identify the interface elements locations on the finite element model and may need some specific parameter calibrations.

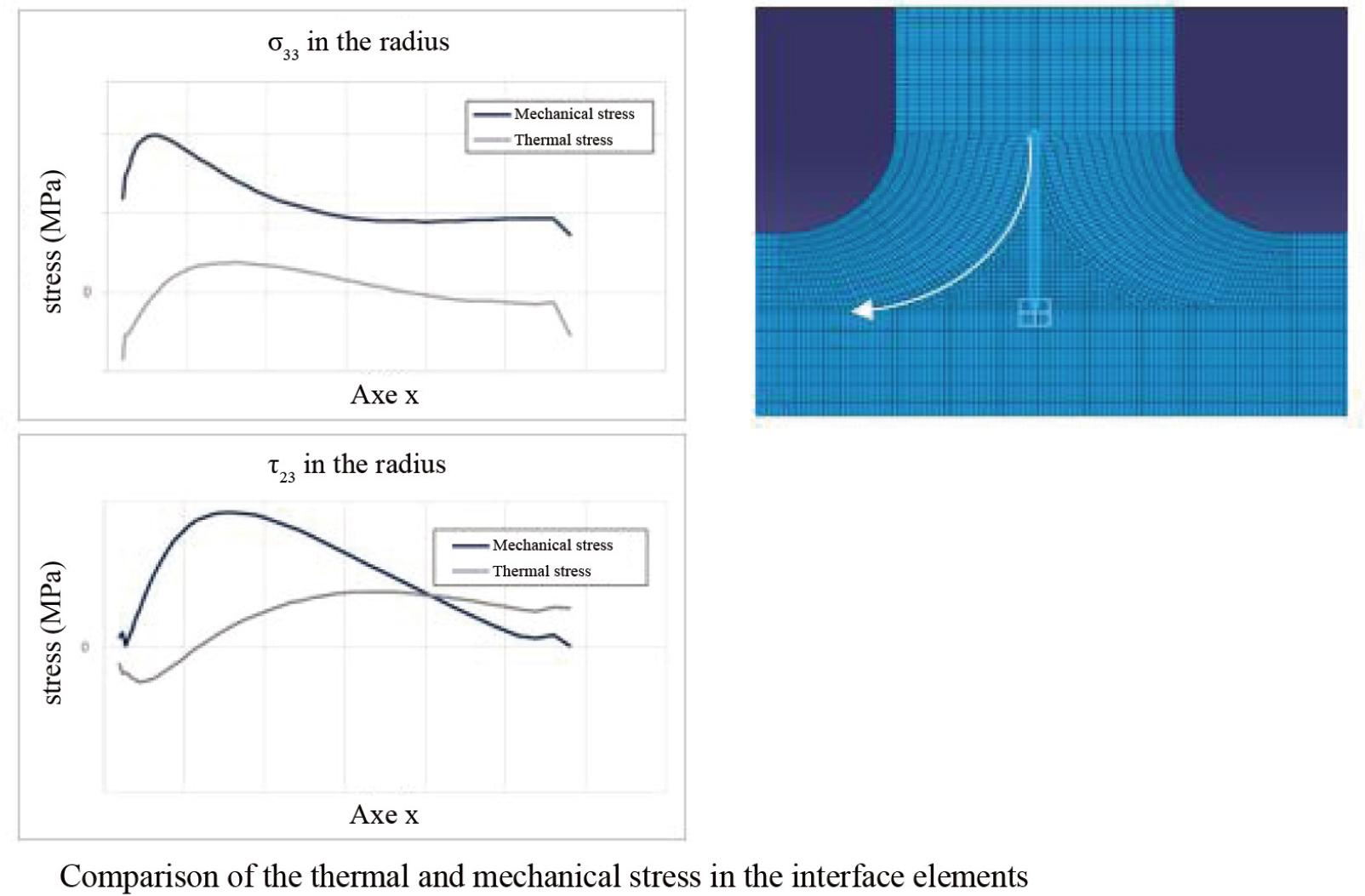

When addressing a composite structure composed of several elements cured together, the question of the relative importance of the manufacturing internal stress has to be addressed. In particular, the thermal stress due to CTE mismatch between different cured elements when the structure cools down after curing may have to be considered. In the stiffener architecture, the presence of a filler may lead to manufacturing thermal stress, particularly in the transverse direction. This has been checked by analysis, which shows that the internal thermal stresses are low compared to the mechanical stresses, in particular where the damage initiation occurs, and will not impair the identification of the model parameters.

As this 3D local model cannot be used in large-scale simulation representing a complete A/C component like a wing structure, it has to be simplified. For that purpose, the 3D elements are replaced by 2.5D plate elements while 3D interface elements are kept. Connecting elements have to be added as the 2.5D elements used must be meshed at their neutral fiber. It has been verified that the stress level in the interface elements remains similar to the one computed with the 3D model. However, due to the difference in the mesh size, all the damage parameters have to be re-identified for this specific model.

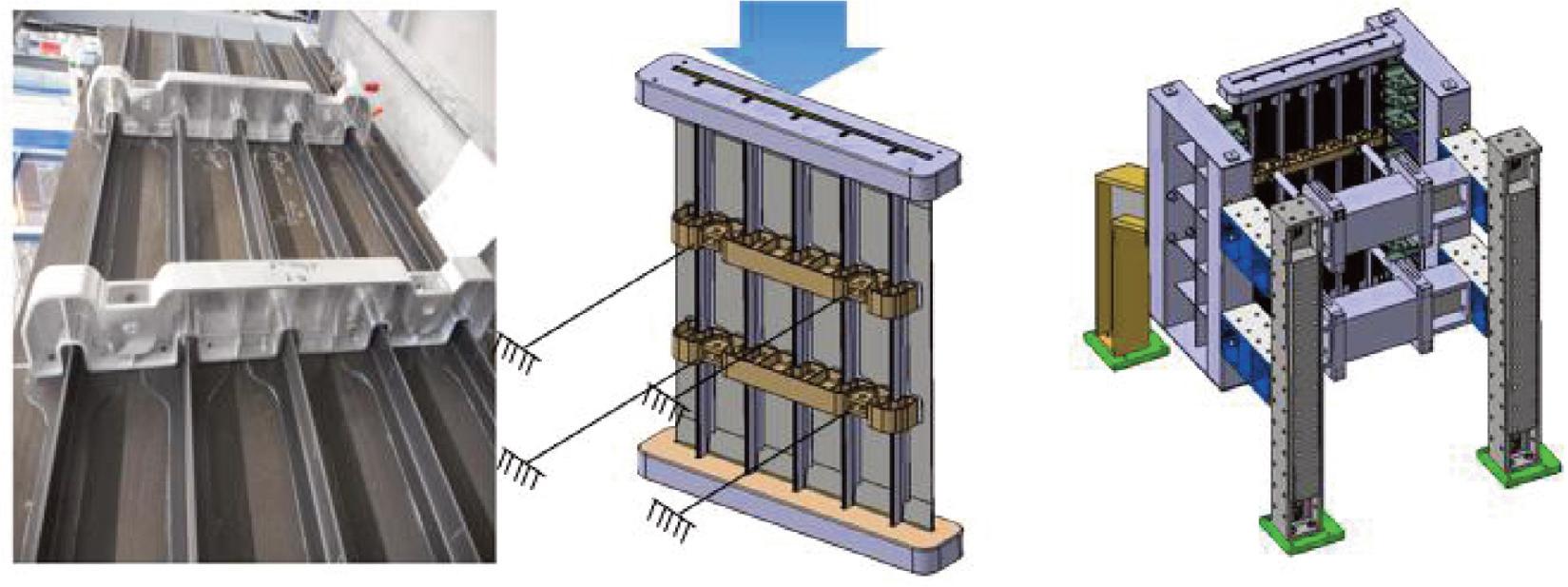

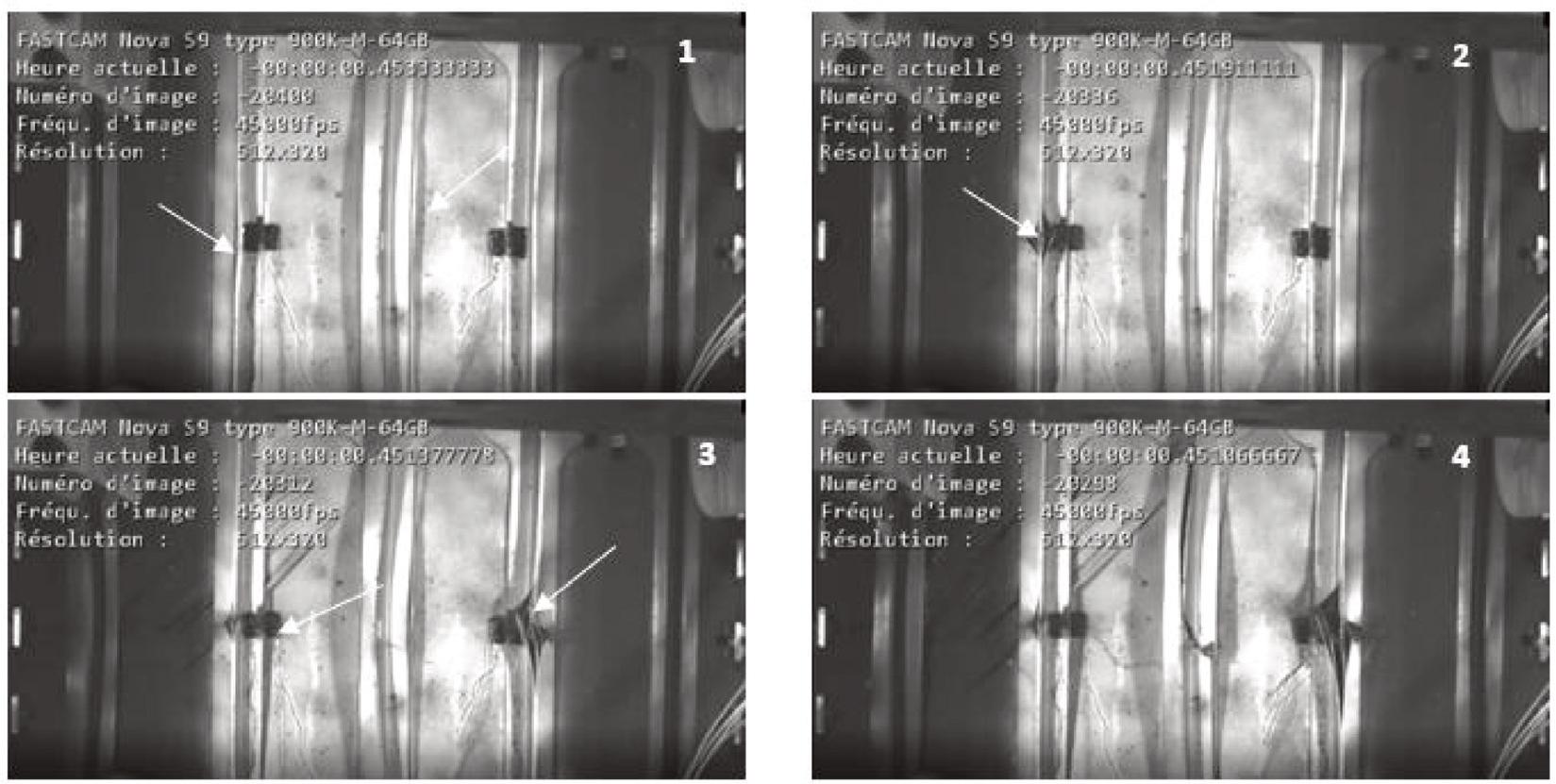

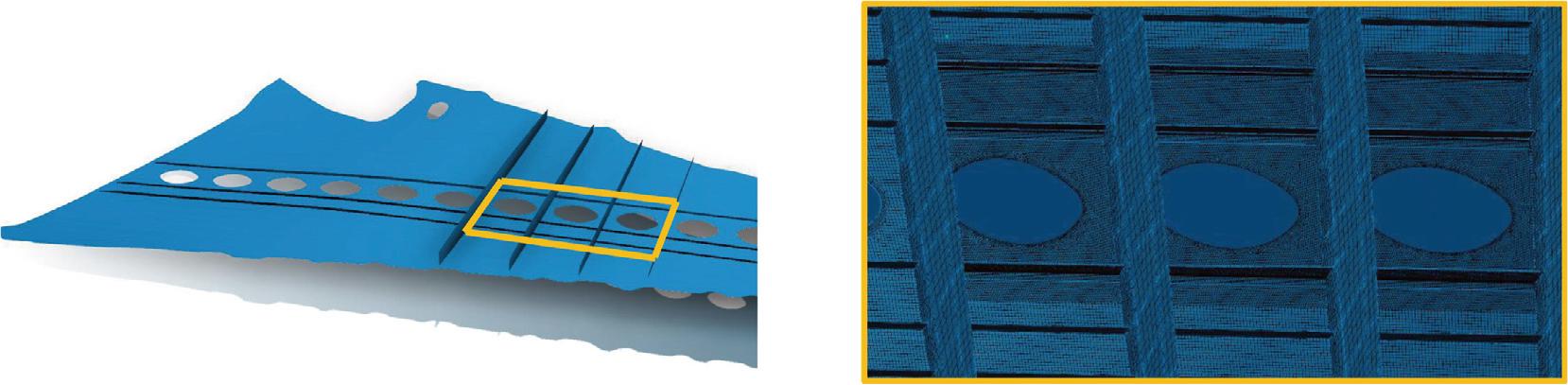

A large multi stiffened panel has been tested. The test specimen is 1700 mm long and 800 mm large. It is 3 rib step long and includes 5 stiffeners. The specimen also includes two dummy ribs connected to the panel by fasteners. The central stiffener has been artificially disbonded between the ribs by insertion of a Teflon patch during the manufacturing process. The panel was clamped at both extremities and supported at rib locations. It was loaded in compression until buckling of the central skin bay and then up to failure. The specimen was equipped with numerous strain gauges to catch the skin buckling and the stiffeners buckling in different bays. A DIC was used on the central area where a stiffener is disbonded and a high speed camera at 45 000 is recorded the panel failures.

The central bay buckling appears at 880 kN, then the lateral stiffeners start to bend inward due to the deformation of the skin. A small lateral bending of the central stiffener was observed during the loading. A brutal failure occurred at 1495 kN. The high-speed camera shows that the central stiffener appears to present a flange buckling a few images before the complete failure. The first visible damage was observed in the lateral stiffener tops in the middle of the central bay; the damages propagated and led to the stiffener disbond and the final brutal failure of the panel. During the test, it was verified that the disbond did not propagate during the loading which means that the fasteners were able to contain the disbond.

The model is composed by plate (2.5D) elements, the ‘simplified’ damage model described above have been used on lateral stiffeners of the central bay. The other stiffeners are simply modelled by 2.5D plate elements representing the blade and the flange and the filler is modelled by bar elements. Ribs are taken into account by boundary conditions. The panel extremities are loaded by imposed displacements.

A first simulation was run without activating the damage capacity of the interface elements. It predicted a buckling of the central bay at 825 kN, the load increased until the flange buckling of the central stiffener, and the local buckling of the lateral stiffener web; then the panel collapsed at a maximum load of 1380 kN which is 8% below the test results. The strain levels at the gauge locations show good correlation with the measurements in particular during the post-buckling regime.

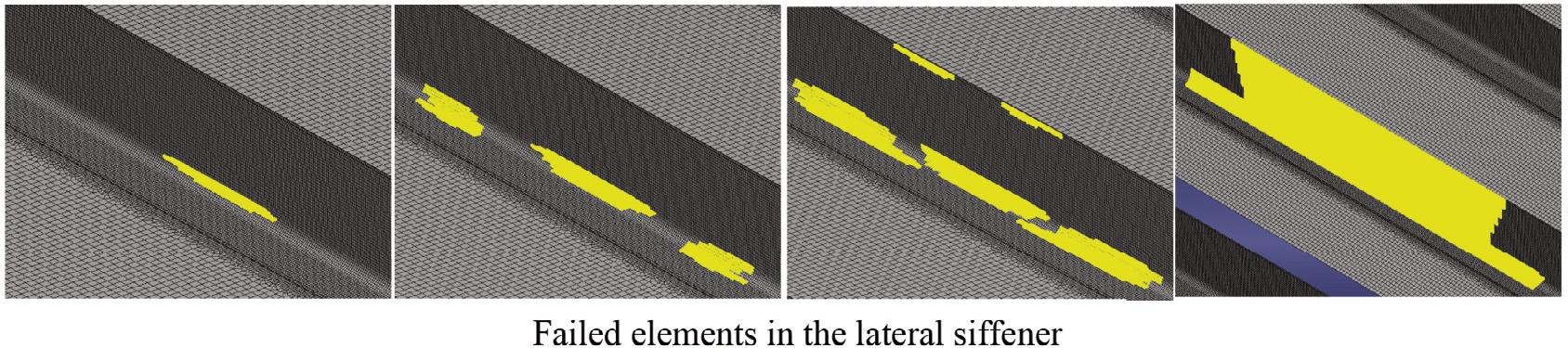

A second simulation has been run with the damage capability activated. The maximum load reached during this simulation was identical to the one obtained previously. No damage initiation was predicted until the central stiffener collapsed. At this load level, the damages were initiated in the central area of the lateral stiffener at the location where the stiffener buckling appeared:

first at the stiffener foot, in the external radius and under the filler (local disbond) where the stiffener is bent inward. The failure mode is predominantly in tension (mode 1),

then in the stiffener top between the L elements where the failure initiation is predominantly due to the shear stress while the damages in the radius increase.

The failure initiation occurs at the maximum load however it is clearly a consequence of the buckling of the lateral stiffeners, which leads to a rapid increase of the stress in the interface elements and the subsequent failure of the stiffeners. The subsequent damage propagation is very rapid and lead to the complete failure of the panel. This result is consistent with the observations made by the high-speed camera.

It has been shown that the model was able to predict accurately the buckling modes, the associated loads, and the stress level in the panel in the post-buckling regime. The locations of the damages and the load at the damage initiation are consistent with the observations made.

The damage model has been inserted into a complete FE model of the wing box demonstrator of civil aircraft, as a local patch connected to the rest of the model by 2D/3D connecting elements and mesh degeneration. The objective is to check the damage initiation load relative to the skin buckling level, and to verify that the damage initiation is consecutive of the buckling of the lateral stiffener as observed in the large panel test.

Several locations have been considered:

in the area where the skin buckling margin is minimal

close to the manhole doors

close to the front spar where the skin bay after the stiffener disbond is the largest one

For each of these zones, the procedures applied were identical: A first simulation is made (with all stiffeners bonded and the damage capability deactivated) to check that the integration of the patch does not impair the internal load distribution nor the buckling modes of the original model. Then the central stiffener of the patch is disbonded and the damage capability of the interface elements are activated. The wing is loaded up to the buckling of the skin bay and the subsequent buckling of the adjacent stiffeners.

ZONE 1:

ZONE 2:

ZONE 3:

The simulations did not shown any damage initiation up to limit load. The buckling of the lateral stiffeners appears above limit load demonstrating the robustness of the structure. For each of these simulations, the computation time remains below 3 days on a standalone computer.

A damage model has been developed to predict the disbond of a stiffener under variable loading conditions. Its simplicity allows its integration into finite element models of large aircraft components at a reasonable computing time.

This damage model is limited to the prediction of the delamination/disbond where the damage zones have been previously identified and characterized. For these zones, the identification of the model parameters and the simulation accuracy must be done at the lower level of the test pyramid on specimens representative of the design detail, in particular covering the design space and loading modes of the structure. For the problem addressed in this paper, a single set of model parameters have been identified and has been sufficient to simulate the damage initiation and the specimen’s failure for the critical location identified in the coupon tests and in the large panel test in the postbuckling regime. It is not necessary a general result and the use of different set of parameters applicable to different zones is not an issue. Due to the stiffener design, it is necessary to conduct preliminary simulations of element specimens using 3D models. Once the damage model is set up, simplifications can be made according to the specific problem to which it is applied. The relevance of these simplifications is verified through the test pyramid.

Industrial structural details such as the one investigated in this paper, often exhibit complex interacting damage modes such as matrix cracking and delamination. The consideration of the coupling between these modes is still a challenge. Although not representing these complex mechanisms, the damage model presented here has been able to predict the failure of the interface elements at different locations identified in the stiffener structures. The simplicity of the plasticity criterion – empirically calibrated – appears to be a convenient, easy-to-use and versatile way of adjusting the critical energy release rate curve for the structures investigated here. It also simplifies the parameter identification and avoids some of the numerical issues usually associated with more complex methods.

More investigations are in progress to validate its applicability to other structures.