Essential oils are natural volatile mixtures of complex compounds that are the result of the secondary metabolism of aromatic plants. Thanks to their different chemical composition, essential oils have several biological activities such as digestive (1), anti-inflammatory (2), antimicrobial, antiviral (3), antioxidant (4), hepatoprotective (5), and anticancer (6). Given that there is a huge increase in the resistance of microorganisms to the use of synthetic antimicrobial agents, the attention of the scientific community has been increasingly focused in recent years on the results of studies that examine the effect of various active metabolites of plant origin, among which essential oils and their components stand out the most.

Juniperus communis L. (J. communis), popularly known as juniper, pine, or spruce, is an evergreen shrub or lower tree from the Cupressaceae family. This perennial plant is distributed throughout the Northern Hemisphere, in the mountainous areas of Europe (Alps, Pyrenees, Dinarides, Carpathians), Central Asia, North America, and less often in North Africa. In Serbia, it occurs naturally mostly in the mountains of Kosovo and Metohija (Šara, Mokra Gora, Kopaonik, Rogozna) and Southwestern Serbia (Tara, Zlatibor, Golija, Pešter) (7), which especially applies to areas of degraded forests and abandoned agricultural areas. This plant species has a long history of use in folk medicine as a diuretic, anti-inflammatory, antiseptic, stomachic, anti-rheumatic, and anti-diabetic, for kidney and bladder inflammation (8,9,10,11). It is most important bioactive ingredient is essential oil, which has a wide range of applications (food, cosmetic, pharmaceutical industry, veterinary) and high commercial value. The characteristic composition of the essential oil obtained by steam distillation from ripe, unfermented berries of J. communis mostly includes terpene hydrocarbons (monoterpenes up to 85 %): α-pinene (20–50 %), myrcene (1–35 %), sabinene (<20 %), limonene (2–12 %), β-pinene (1–12 %), caryophyllene (<7 %), terpinene-4-ol (0.5–10 %), then sesquiterpenes (up to 27%) and their oxidized derivatives (up to 4 %) (7). The wide distribution of this species, due to the different effects of environmental factors, leads to variability in terms of the chemical composition and biological activity of its metabolites (12). Variations in chemical and structural type are exactly what makes essential oils functionally versatile and thus more interesting to the scientific public. Variability of the chemical composition of J. communis essential oil is also confirmed by a wide range of values in the requirements of the European Pharmacopoeia (European Pharmacopoeia 8). Among the activities of juniper essential oil tested so far, the greatest application potential is reflected in its antimicrobial activity against a wide range of bacteria, the effect of which is determined by the chemical nature of the metabolites, its concentration, and the taxonomic properties of microorganisms (13–14). Considering the potentially toxic and carcinogenic effects of synthetic antioxidants in humans and animals their replacement with natural antioxidants is beginning to be justified. Depending on the presence of active components, the essential oil of juniper berries shows positive effects in slowing down the lipid peroxidation of foods of animal origin (15), as well as antiradical activity against the DPPH radicals (16). However, scientific reports emphasizing the potential of juniper essential oil for health purposes, as well as in food production and storage, are rare.

This work aims to determine the chemical composition of J. communis oil from different localities in the Republic of Serbia and examine its antimicrobial and antioxidative effects together with chemometric analysis and principal component analysis (PCA), and thus contribute to the results of previous research, considering the qualitative and quantitative differences of J. communis essential oils of different geographical origins. The essential oil compositions of the four samples were analyzed using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometer (GC-MS). The samples were then classified by PCA and hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) to determine their relationships. Furthermore, with this work, we want to clarify in more detail whether the biological potential of J. communis essential oil is mainly the result of the activity of the components present in the highest concentrations or whether the investigated antimicrobic and antioxidative effects arise from the synergism of all present molecules.

Drug samples were collected from wild juniper bushes from four different locations in the Republic of Serbia (Kopaonik (JC1), Mačkat (JC2), ), Takovo (JC3), and Bavanište (JC4)) in October 2019. Table 1 displays the meteorological data for the four habitats from which samples were collected. After collection, the drug was cleaned from the leaves, then properly dried and stored under conditions that do not allow spoilage and contamination (dry environment with low humidity levels; temperature between 10–20°C; dark container; sealed container). The fruits are crushed in an electric mill (IKA® A11 basic) and thus prepared for steam distillation. The preparation of the plant material as well as the isolation of the essential oil were carried out in the laboratory of the Faculty of Medical Sciences of the University of Kragujevac.

The collection sites, meteorological data, and yields of oils from the four J. communis samples and the correlation coefficients between four environmental factors and essential oil yields.

| Sample | Place | Average Altitude (m) | Temperature1 (°C) | Precipitation1 (mm) | Humidity1 (%) | essential oil yield (wt%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JC1 | Kopaonik | 1710 | 9.6 | 966.04 | 79.83 | 1.71 |

| JC2 | Mačkat | 600 | 9.74 | 995.26 | 78.58 | 1.98 |

| JC3 | Takovo | 330 | 11.7 | 818.82 | 75.83 | 1.58 |

| JC4 | Bavanište | 80 | 13.38 | 768.34 | 69.83 | 1.56 |

| Correlation coefficients | 0.273 | −0.756 | 0.871 | 0.637 |

The annual average meteorological data (2015–2019) of four locations from the Republic Hydrometeorological Service of Serbia (annuals bulletin for Serbia, https://www.hidmet.gov.rs) and “Weather Atlas” (https://www.weather-atlas.com)

Oil yields (wt.%) = Weight (crude oil)/Weight (dry fruit) × 100;

One hundred grams of chopped juniper fruits were placed in a glass balloon and then subjected to hydrodistillation. During two hours, water was heated in a vessel with a flat bottom (steam generator) at a temperature of 100 (±10) °C. The essential oil was separated in a Florentine bottle, where the separation of the two phases - oil and water phase - could be observed. The essential oil was separated by decantation, which was then stored in screw-cap vials with adequate labeling.

Analyzes were performed on an Agilent 7890A gas chromatograph equipped with an Agilent 5975C mass-selective detector (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and a capillary column (HP5-MS, 30 m × 0.25 mm, 0.25 μm). As the mobile gas phase, helium (He) gas was used with a constant flow rate of 1 ml/min. The injector temperature was set to 230 °C, while the detector temperature was 250 °C. The column temperature was linearly changed in the range from 40 to 220 °C, at a rate of 3 °C/min. The injected volume of the sample (dissolved 1/1 in hexane (Fisher, UK), v/v) is 1.0 μl in a split ratio of 1:50. Mass spectra were recorded at 70 eV in the range m/z 40–450. The identification of the detected compounds was performed by comparing their mass spectra with spectra from the spectral database NIST08 (National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD, USA), which contains 192,108 spectra of different compounds. Quantification was performed by the method of normalization of the areas under the peaks, that is, based on the correlation of the areas of the peaks and the percentage representation. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of the chemical composition of the obtained essential oils was carried out in the laboratories of the Institute of Public Health in Kragujevac.

The antimicrobial activity of the essential oil was tested against nine microorganisms. The experiment involved eight strains of bacteria (five standard strains (Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923, Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633, Proteus mirabilis ATCC 12453, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853, and Escherichia coli ATCC 25922) and three isolates (Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and Salmonella enterica)). Also, one yeast standard strain (Candida albicans ATCC 10231) was tested. All isolates were a generous gift from the Institute of Public Health, Kragujevac. The other microorganisms were provided from the collection held by the Microbiology Laboratory Faculty of Science, University of Kragujevac.

The bacterial suspensions were prepared using the direct colony method. The turbidity of the initial suspension was adjusted with a densitometer (DEN-1, BioSan, Latvia). When adjusted to the turbidity of the 0.5 McFarland standard, the bacterial suspension contained approximately 108 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL, while the yeast suspension contained 106 CFU/mL. Ten-fold dilutions of the initial suspension were additionally prepared in sterile 0.85% saline.

Antimicrobial activity was tested by determining the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) and minimum microbicidal concentrations (MMC) using the microdilution plate method with resazurin (17). The 96-well plates were prepared by dispensing 100 μL of nutrient broth (Mueller–Hinton broth for bacteria and tryptone soy broth for yeast) into each well. A 100 μL aliquot of the stock solution of the tested essential oil, dissolved in Tween 40 at a 1:1 ratio, was added to the first row of the plate. Twofold serial dilutions were then performed using a multichannel pipette. The resulting concentration range for the JC3 sample was 500 to 0.98 μL/mL, while for the JC1, JC2, and JC4 samples, the range was 2000 to 3.91 μL/mL.

The microtiter plates were inoculated with suspensions to achieve final concentrations of 5 × 105 CFU/mL for bacteria and 5 × 103 CFU/mL for fungi. Microbial growth was monitored using resazurin (Alfa Aesar GmbH & Co., KG, Karlsruhe, Germany), a blue dye that turns pink when reduced by viable cells. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 hours (bacteria) and 28°C for 48 hours (yeasts). The MIC was the lowest extract concentration preventing the color change of resazurin. MMC was determined as the lowest concentration showing no microbial growth after plating samples onto nutrient agar. Each test included growth control and sterility control. All experiments were performed in duplicate.

Tetracycline and fluconazole were used as positive controls. The antibiotic tetracycline (Pfizer Inc., USA) was dissolved in a nutrient liquid medium, Mueller–Hinton broth (Torlak, Belgrade, Serbia), while the antifungal agent fluconazole (Pfizer Inc., USA) was dissolved in tryptone soya broth (Torlak, Belgrade, Serbia).

The ability to scavenge free radicals was tested using DPPH radical according to the method described by Mishra et al (18). First, a solution of DPPH (Alfa Aesar GmbH & Co., Germany) in methanol (Fisher, UK) was prepared at a concentration of 0.05 mg/ml and stored in a darkened bottle in the refrigerator until the experiments were performed. Then, a series of standard solutions of the tested extracts and standards in methanol was made (ie 1000, 500, 250, 125, 62.5, and 31.25 μg/ml). Test tubes were filled with 200 μl of solutions containing either tested extracts or standards at specified concentrations, along with 2 ml of DPPH solution. After intensive mixing, the mixture was incubated in the dark for half an hour. After incubation, the absorbance of the solution was measured at 517 nm compared to the control. Ascorbic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and 6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid (Trolox, Acros Organics, Belgium) were used as positive controls. The concentration of DPPH radicals was calculated according to the equation:

The ability to neutralize free radicals was tested using ABTS radicals according to the previously described method by Tabassum et al. (19) with modification. During the preparation of the experiment, the mixture of 7 mM ABTS (Alfa Aesar GmbH & Co., Germany) and 2.45 mM potassium persulfate (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was incubated at room temperature without the presence of light for 24 hours. This solution was diluted until an absorbance of 0.700±0.02 at 734 nm was achieved. A volume of 300 μl of extract or standard solution was mixed with 600 μl of ABTS solution. This mixture was incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Absorbance was measured at 734 nm. Ascorbic acid and Trolox were used as positive controls. The ABTS radical concentration was calculated according to the equation:

Ak denotes the absorbance of the control (which contains all reagents, except the tested extract or standard), and Au is the absorbance of the sample. Based on the obtained values, a nonlinear calibration curve was constructed, which was used to determine the concentration of the tested sample that inhibits 50% of ABTS radicals (IC50).

ANOVA test with α=0.05 was used to determine the differences between the assays. The correlation coefficients between yields and compounds of essential oils and the main ecological factors of collection locations were calculated. PCA was employed to identify the interrelations among the essential oils of J. communis obtained from the four places. HCA was performed based on the between-group linkage to classify the four oil samples examined. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 21.0.

The information from the four samples of J. communis, including the collection sites, meteorological data, essential oil yields, and correlation coefficients between four environmental factors and the essential oil yields, is summarized in Table 1. The essential oil extracts from all four samples were colorless. Yields of essential oils (yields, g/g, dry fruit) obtained from the four samples ranged from 1.56 % to 1.98 %. The yield of JC2 (1.98 %) was higher than the others, followed by JC1 (1.71 %), JC3 (1.58 %), and JC4 (1.56%). Reports suggest that the yields of essential oils in plants can be influenced by altitude, precipitation, temperature, and other ecological factors of their habitats. (20). Compared with the other three ecological factors, precipitation showed a strongly positive correlation (0.871) with essential oil yields, suggesting it could be a dominant environmental factor affecting the essential oil yields of J. communis from various regions. Labokas and Ložienė also observed the impact of precipitation on essential oil yield in plants (21).

Examination of the essential oil of juniper fruit from different locations in the Republic of Serbia included the preparation of plant material, isolation of the essential oil by hydrodistillation, phytochemical analysis of the mentioned oils by a combined chromatographic-spectroscopic method (gas chromatography-mass spectrometry) and comparison of the obtained results.

By analyzing the chemical composition of juniper essential oils in samples from Kopaonik, Mačkat, Takovo, and Bavanište, 23 compounds were separated and identified as shown in Table 2.

Chemical composition of J. communis essential oils from different habitats

| NO | Compound | Retention time (min) | Relative abundance (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JC1 | JC2 | JC3 | JC4 | |||

| C1 | α - thujen | 5.392 | 2.23 | 1.72 | / | 1.24 |

| C2 | α-pinene | 5.559 | 32.68 | 41.95 | 51.10 | 46.82 |

| C3 | β-phellandrene | 6.541 | 24.77 | / | 6.43 | 12.27 |

| C4 | Sabinene | 6.547 | / | 17.82 | / | / |

| C5 | Tricyclene | 6.605 | 2.19 | 2.57 | 2.23 | / |

| C6 | β-terpinene | 6.593 | / | / | / | 2.32 |

| C7 | β-pinene | 7.040 | 14.09 | 13.92 | 9.84 | 9.99 |

| C8 | D - limonene | 8.005 | 4.16 | 3.78 | 4.86 | 3.81 |

| C9 | Terpinolene | 9.660 | 1.40 | 1.02 | / | 1.10 |

| C10 | α-cubebene | 16.798 | 0.76 | 0.80 | 2.08 | 0.76 |

| C11 | Copaene | 17.480 | / | / | 1.18 | / |

| C12 | β - elemene | 17.925 | / | / | 1.41 | / |

| C13 | β-caryophyllene | 18.583 | 1.69 | 2.42 | 1.39 | 2.26 |

| C14 | α - caryophyllene | 19.443 | 1.22 | 1.53 | 1.42 | 1.31 |

| C15 | γ-cadinene | 20.130 | 9.56 | 6.45 | / | / |

| C16 | Humulene | 20.488 | / | 0.68 | / | / |

| C17 | γ - elemene | 20.494 | 0.80 | / | / | 0.65 |

| C18 | β - cubebene | 20.136 | / | / | 11.09 | 4.36 |

| C19 | Bicyclogermacrene | 22.452 | / | / | 2.58 | / |

| C20 | α - elemene | 20.714 | 0.85 | 0.71 | 2.03 | 0.57 |

| C21 | Cadinene | 21.164 | 0.70 | 0.88 | 1.18 | / |

| C22 | Aristolene | 21.927 | / | 4.28 | / | / |

| C23 | Elixene | 21.938 | 2.93 | / | / | 3.72 |

Examination of the chemical composition of these essential oils samples revealed the presence of several monoterpene and sesquiterpene compounds.

The most abundant compound in all samples is α-pinene (C2, 32.68–51.10 %), as shown in previous studies (22,23). β-pinene (C7), limonene (C8), α-cubebene (C10), α-elemene (C20), β and α-caryophyllene (C13, C14) were identified in all examined oils, but their quantitative representation differed. The content of β-pinene in the oil of fruits originating from higher altitudes (JC2 and JC1) was above 10 %, while its content was below 10 % in the oils obtained from the fruits of areas of lower altitudes (JC4 and JC3). The terpenes sabinene (C4, 17.82 %), aristolene (C22, 4.28%), and humulene (C16, 0.68 %) were identified in the drug oil originating from JC2, while their presence was not confirmed in the other oils. In the essential oil originating from JC3, the presence of the following compounds was confirmed: bicyclogermacrene (C19, 2.58 %), β-elemene (C12, 1.41 %), and copaene (C11, 1.18 %), which were not found in other oil samples. β-terpinene (C6) is a terpene that, with a percentage of 2.23%, was an integral part of only the essential oil obtained from juniper originating from JC4.

The representation of monoterpene secondary metabolites in all four essential oils is significantly higher than the content of sesquiterpenes. It has been shown that altitude has an influence on the composition of essential oils (24). α-pinene (C2), whose representation of over 50 % was the highest in juniper fruit essential oil originating from JC3, may emphasizes the consistency of certain chemical profiles within different geographical regions. There is a higher content of β-pinene (C7) in areas of higher altitude, as well as γ-cadinene (C15) which was identified only in oils from higher altitudes. This can certainly be explained by the fact that different altitudes have different effects on the amount of precipitation, day and night temperatures, relative humidity, and exposure to wind. At high altitudes, there is greater exposure to sunlight and low temperatures, which in plants leads to changes in morphology and physiology, and therefore to changes in the production and composition of secondary plant metabolites. A noticeable difference is observed in the presence and concentration of other terpenes such as β-phellandrene (C3), sabinene (C4), β-pinene (C7), D-limonene (C8), α-cubebene (C10), and others, which further emphasizes the complexity of the influence of environmental factors on the chemical composition of essential oils. The high prevalence of α-pinene (C2) and β-phellandrene (C3), as the main components in the oil from JC1, corresponds to the qualitative analysis of the essential oil of juniper berries from the central part of Portugal where α-pinene and β-phellandrene were also identified as the two main components of the essential oil (25).

The identification of specific terpenes in different samples, such as sabinene (C4), aristolene (C22), and humulene (C16) identified only in the JC2, bicyclogermacrene (C19), β-elemene (C12) and copaene (C11) in the JC3, as well as β-terpinene (C6) in the JC4, indicates specific adaptations of plants to local conditions, which can be useful in identifying the geographical origin of essential oils and potentially useful in situations that require the application of certain chemical components.

Differences in the quantitative and qualitative composition of essential oils, which are the result of various factors such as altitude, geographical location, ripeness of the fruit, age of the plant, and production method, highlight the complexity of factors that affect the chemical profile of the essential oil (26,27). These factors not only affect the quality and characteristics of essential oil but also represent the basis of the individual biological properties of juniper essential oil (15,23). The present compounds have a high biopotential and previous studies have confirmed their various biological activities. This tells us that the essential oil of the juniper fruit is a source of natural active compounds with a wide application potential in the pharmaceutical industry as natural bioactive ingredients, in the cosmetic industry for the development of products with specific therapeutic properties, as well as in the food industry as natural preservatives or flavorings (14,15).

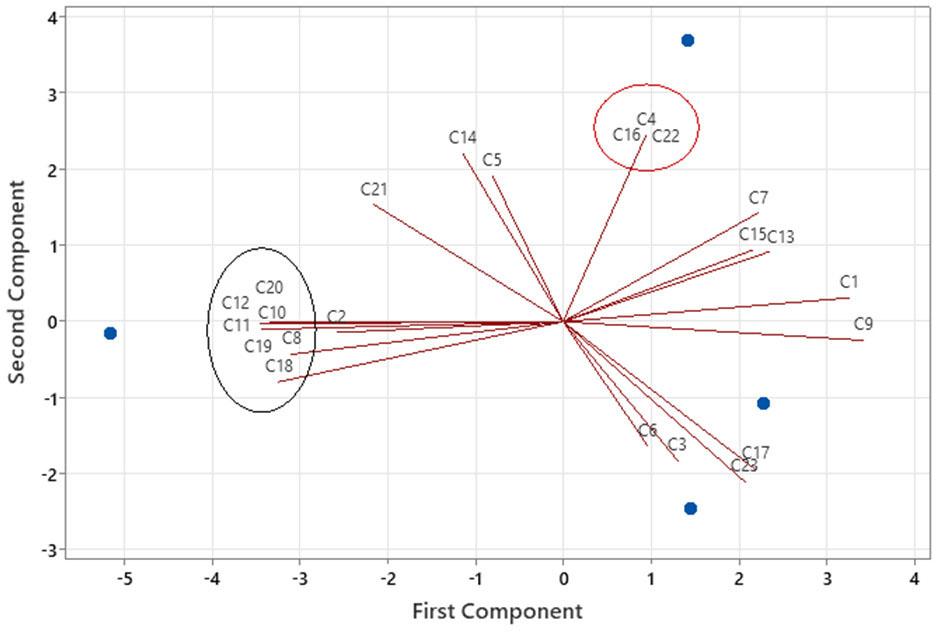

Hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) and principal component analysis (PCA) were used to examine the variability in the chemical composition of four samples of juniper essential oils (JC1, JC2, JC3, and JC4). PCA was performed on a total of 23 identified compounds.

Principal component 1 (PC 1) explains 52.09 % of the variance and is strongly positively correlated with the following compounds: D-limonene (C8, 0.938), α-cubebene (C10, 0.998), copaene (C11, 0.999), β-elemene (C12, 0.999), β-cubebene (C18, 0.934), bicyclogermacrene (C19, 0.999) and α-elemene (C20, 0.980). All mentioned compounds belong to the group of sesquiterpenes except D-limonene (C8) which belongs to monoterpenes.

Principal component 2 (PC 2) explains 30.11 % of the variance and is strongly positively correlated with the following compounds: sabinene (C4, 0.893), humulene (C16, 0.893), and aristolene (C22, 0.893). Sabinene (C4) is the only compound that belongs to the monoterpene group, while the other compounds belong to the sesquiterpene group. The arrangement of identified compounds in the context of PC 1 and PC 2 is presented in Figure 1.

The loadings of each compound for principal components 1 and 2. The components with the highest correlation by component are encircled (PC1 - black line; PC2 - red line)

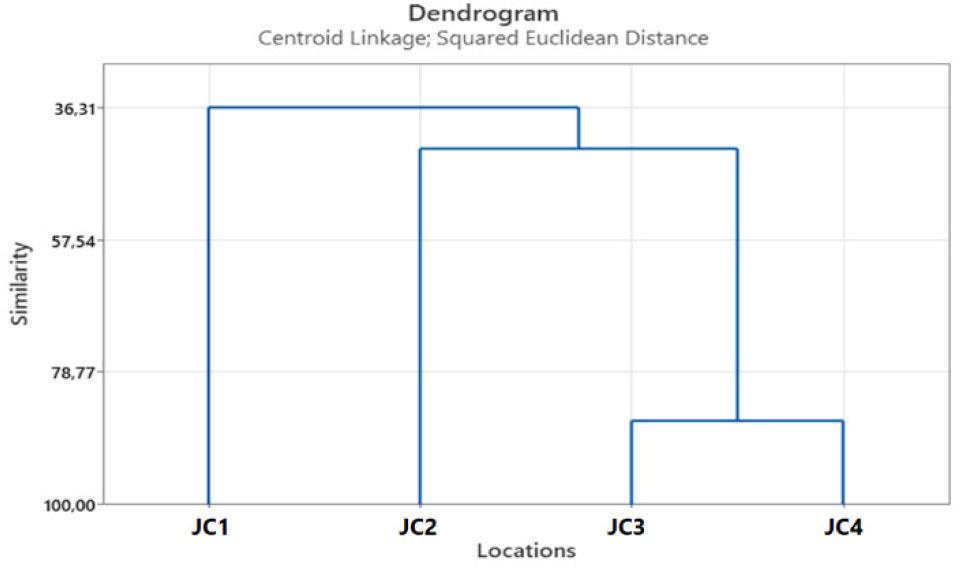

HCA was conducted using Centroid Linkage and Squared Euclidean Distance. It was shown that there are two clusters, where one cluster consists of essential oil from junipers collected on JC1, while the other cluster consists of essential oils obtained from junipers collected at the remaining three locations. Also, it was shown that essential oils from juniper originating from JC3 and JC4 are very similar. The HCA dendrogram is presented in Figure 2.

Dendrogram obtained by hierarchical cluster analysis of juniper essential oils from four different locations in the Republic of Serbia.

The results of in vitro testing of the antimicrobial activities of the tested essential oils, tetracycline, and fluconazole are shown in Table 3. The intensity of antimicrobial action varies depending on the microorganism species and the type of essential oil. In general, the tested juniper berry essential oil showed good activity, with the JC4 sample being the most effective.

The antimicrobial activity of J. communis essential oils

| Tested species | JC1 | JC2 | JC3 | JC4 | Tetracycline/Fluconazole | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC | MMC | MIC | MMC | MIC | MMC | MIC | MMC | MIC | MMC | |

| B. subtilis ATCC 6633 | 500 | 500 | 15.63 | 62.50 | 125 | 1000 | 62.50 | 62.50 | 1.95 | 15.63 |

| S. aureus | 1000 | >2000 | <3.91 | 31.25 | 125 | 500 | 7.81 | 31.25 | 0.98 | 15.62 |

| S. aureus ATCC 25923 | 500 | 1000 | 15.63 | 31.25 | <3.91 | 7.81 | 7.81 | 62.50 | 0.22 | 3.75 |

| P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 | 500 | 500 | 7.81 | 62.50 | <3.91 | 15.65 | 7.81 | 250 | 62.5 | 125 |

| P. mirabilis ATCC 12453 | 500 | 1000 | 31.25 | 31.25 | 62.50 | 125 | <3.91 | <3.91 | 125 | 125 |

| E. coli | >2000 | >2000 | 7.81 | 31.25 | 31.25 | 62.50 | <3.91 | 15.65 | 15.63 | 31.25 |

| E. coli ATCC 25922 | 500 | 1000 | <3.91 | <3.91 | 7.81 | 15.63 | <3.91 | <3.91 | 15.63 | 31.25 |

| S. enterica | >2000 | >2000 | 7.81 | 62.50 | 250 | 500 | <3.91 | 15.65 | 15.63 | 31.25 |

| C. albicans ATCC 10231 | 250 | 1000 | <3.91 | 62.50 | <3.91 | 15.65 | <3.91 | 15.65 | 31.25 | 1000 |

MIC-minimum inhibitory concentrations; MMC-Minimum microbicidal concentration; Values are expressed in μl/ml for essential oils and in μg/ml for tetracycline and fluconazole

The JC2 sample demonstrated the best antimicrobial effect (MIC ranging from <3.91 µl/ml to 31.25 µl/ml), followed by the JC4 sample (MIC ranging from <3.91 µl/ml to 62.5 µl/ml). The JC3 sample exhibited moderate activity (MIC ranging from <3.91 µl/ml to 250 µl/ml), while the JC1 sample showed a limited and selective effect (MIC ranging from 250 µl/ml to >2000 µl/ml).

The strongest antibacterial effect of the JC2 sample was observed against E. coli ATCC 25922 (MIC and MMC values at <3.91 µl/ml). The JC4 sample showed the strongest effect on P. mirabilis ATCC 12453 and E. coli ATCC 25922 (MIC and MMC values at <3.91 µl/ml). The JC3 sample exhibited stronger activity against S. aureus ATCC 25923 (MIC at <3.91 µl/ml; MMC at 7.81 µl/ml) and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 (MIC at <3.91 µl/ml; MMC at 15.65 µl/ml).

The JC4 and JC3 samples also demonstrated the best antifungal effects (MIC at <3.91 µl/ml; MMC at 15.65 µl/ml), followed with JC2 sample (MIC at <3.91 µL/mL; MMC at 62.50 µL/mL).

The positive antimicrobial effect of the essential oil from the JC2 sample can be attributed to the high content of α-pinene (C2), as such indications have already been presumed (28,29). Sabinene (C4), identified only in the essential oil from JC2, has already shown effectiveness of inhibiting the growth of certain bacterial strains (30), so we can assume its additive antimicrobial effect in this oil. The same can be said for sesquiterpene such as β-caryophyllene (C13), present in all samples with the highest abundance in the oil sample from JC2, known for its anti-inflammatory properties, but studies also indicate its role in antimicrobial activity (31,32). Marčetić et al. (33) observed that the qualitative and quantitative composition of essential oils varies based on the substrates where the species were sampled. These variations explain the differing antimicrobial effects of essential oils from the same species collected in different localities. Furthermore, Hyldgaard et al. (34) highlighted that the antimicrobial activity of juniper essential oil is influenced not only by its major constituents but also by the interactions between major and minor constituents, which can lead to additive or synergistic effects.

Compared to Tetracycline, essential oils show significantly weaker antimicrobial activity. This is not surprising, given that synthetic antibiotics are specifically designed to target key pathways in pathogenic microorganisms with high efficiency. However, the importance of essential oils may lie in their application as complementary therapies, especially in the context of the growing problem of antibiotic resistance. Many studies have shown that combining essential oils with a conventional antibiotic can enhance the antimicrobial effect, suggesting a synergistic interaction between these agents (32,35).

Antioxidant activities of the essential oils were analyzed using free radical scavenging (DPPH and ABTS assays and the results are presented in Table 4.

The antioxidant activity of the J. communis essential oils

| Samples/Standards | DPPH scavenging activity | ABTS scavenging activity |

|---|---|---|

| IC50 (μg/ml) | ||

| JC1 | > 1000 | 896.11 ± 7.02 |

| JC2 | 308.83 ± 3.85 | 237.74 ± 4.61 |

| JC3 | > 1000 | > 1000 |

| JC4 | 966.89 ± 10.83 | 793.66 ± 16.23 |

| Ascorbic Acid | 9.08±1.96 | 8.28±0.24 |

| Trolox | 14.26±3.81 | 12.40±0.40 |

DPPH-1,1-diphenyl-2-picryl-hydrazyl free radical; ABTS-2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) radical; IC50-concentration of the tested sample that inhibits 50% of radicals;

Essential oil from JC2 demonstrates a relatively low IC50 value for both tests (308.83 μg/ml for DPPH and 237.74 μg/ml for ABTS), which indicates a significant ability to neutralize free radicals. JC1 and JC3 are characterized by IC50 values greater than 1000 μg/ml for the DPPH test and high but measurable values for the ABTS test. Essential oil from JC4 sample with IC50 values of 966.89 μg/ml for DPPH and 793.66 μg/ml for ABTS, shows moderate antioxidant activity. α-Pinene (C2), present in high concentrations in all essential oils, is known for its antioxidant activity. Studies have shown that α-pinene effectively neutralizes free radicals and contributes to protection against oxidative stress (36, 37). It is present in the largest amount of essential oil JC2, which also showed the best antioxidant activity. β-Pinene (C7) is present in all tested samples. α-pinene and β-pinene belong to the group of monoterpene hydrocarbons, so their antioxidant effect can probably be explained by the presence of methylene groups in these molecules (37, 38). β-Phelandrene (C3) is present in significant amounts in three essential oil samples (24.77% JC1, 12.27% JC4, 6.43% JC3), and its antioxidant activity has already been confirmed (37). The absence of β-phellandrene in the LC2 may indicate that the combination of different terpenes, and not the presence of a single compound, determines the overall antioxidant activity. D-Limonene (C8), in a previous study, showed its antioxidant activity even at low doses (39), and was also present in all oil samples tested. Its consistent presence may contribute to the baseline level of antioxidant activity in all oils tested, but variations in antioxidant activity suggest that the presence of other compounds plays a key role. β-Caryophyllene (C13), a sesquiterpene with observed antioxidant properties (40), although in small amounts, was present in all oil samples tested. The superior antioxidant activity of JC2 can be attributed to the synergistic effects of its high α-pinene (C2) concentrations, the presence of D-limonene (C8), and the combination of β-caryophyllene (C13) and α-caryophyllene (C14), which together form a complex mix of antioxidant active compounds. JC1 and JC4 with moderate to weak antioxidant activity, show that even the presence of high concentrations of potentially active components (such as α-pinene in JC1) is not sufficient for high antioxidant efficiency without appropriate synergy between the components. Essential oil JC3 with the weakest antioxidant activity, indicates that the absence of key antioxidant terpenes and the potential presence of compounds that do not significantly contribute to antioxidant activity, or even inhibit the activity of other components, may result in lower overall efficacy. It is very difficult to attribute the antioxidant activity of essential oils to only one active principle, considering that essential oils are mixtures of different chemical components. It is important to emphasize that sometimes the biological activity of the oil is not only influenced by the most abundant active principles but that the less abundant components can also have a positive effect on the activity.

The current study compared the yields, compositions, and bioactivities of essential oils extracted from J. communis plants collected from distinct areas in Serbia. The research revealed that precipitation in the habitat was the most influential ecological factor affecting the essential oil yields of the samples. A total of 23 components, rich in monoterpenes and sesquiterpenoids, were identified in the essential oils from the four samples. The chemical variation among the essential oils from the four samples could be strongly influenced by the altitude of the habitats. The four samples could be divided into two clusters according to the variability of their components. The study assessed the antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of essential oils extracted from the four samples. The results suggested that the essential oils from J. communis possess promising potential for applications across several industries, such as food, cosmetics, and pharmacy, owing to their inherent dual antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. The sample from Mačkat (JC2) exhibited superior performance in DPPH, ABTS, and antimicrobial assays, coupled with the highest yield. This implies that J. communis sourced from this location shows the greatest potential for further industrial utilization.