Over the past decade, interest has risen significantly in adopting design approaches, such as design thinking (DT), to drive innovation in the public sector and policy design. With its long-standing history in the commercial sector (e.g., graphic, product, and service design), design has made its mark in the public sector. The emergence of public sector innovation units and labs, and their enthusiastic embrace of co-design approaches (i.e., collective creativity in the design process), is a testament to its influence (Bason, 2014; Blomkamp, 2018; Lewis, McGann, & Blomkamp, 2020; McGann, Blomkamp, & Lewis, 2018; Wellstead et al., 2021; Villa-Alvarez, 2022). While commercial design concepts are relatively new to public policy scholarship, a well-established and distinctly separate public policy design field exists. This approach, rooted in the rationalistic planning discipline, has significantly evolved within the policy sciences. Recently, there has been a growing interest in analyzing the potential of design approaches in public administration and their application to public policy (Howlett, 2020; van Buuren, Lewis, Peters, & Voorberg, 2020). In addition, we found that other interpretations of policy and design fall outside of these two established approaches. The multidisciplinary nature of the field and the use of design concepts by academics and practitioners may lead to potential confusion. The differences among the design approaches to policy may be exacerbated, particularly with the sheer variety of online information, including peer-reviewed articles, books, reports, blogs, courses, and the websites of prominent scholars, practitioners, and policy actors.

This paper is a collaborative effort between a design scholar and a policy scientist that attempts to make sense of what we call the “Policy * Design (1)” field. This field comprises the intersection of design approaches from our respective fields, where policy and design are frequently combined. In defining the Policy * Design field, academic and practitioner perspectives are captured. Our approach is to examine how these concepts are reflected online. To do so, we undertake a Google search engine (GSE) scraping tool (2) exercise. In doing so, we found four distinct combinations of the design and policy concepts, namely “policy design,” “design for policy,” “design in policy,” and “design policy.” Specifically, we argue that the differences in these concepts are more than semantic, but represent distinct fields relevant to academics and practitioners.

We begin by reviewing significant contributions from the design literature and then the well-established policy design field followed by coverage of authors who have considered both traditions. This initial literature review has variations in the interpretation of policy and design concepts. From the Google Search scraping exercise, use mapping tools to identify the Policy * Design fields, their corresponding key authors, country locations, and the types of information each provides, followed by a discussion of our findings. Specifically, we compare and contrast policy design, design for policy, design in policy, and design policy areas and suggest working definitions to differentiate them. Finally, directions for future research are made.

Below, we introduce design from a professional design and a policy science perspective, observing the intersection of both approaches. We highlight the notable scholarly contributions from our respective fields in the policy and design sciences, as well as recent hybrid publications.

The design discipline draws inspiration from Herbert Simon’s (1969) Science of the Artificial. Simon argued that design is “concerned with how things ought to be in order to attain goals and to function” (p.13), which implied an intention of change by conceiving courses of action that could lead to preferred situations. Design (3) as an academic field can be traced to the 1960s with the “design methods movement” and in the late 1980s with the development of Design Studies publications (Cross, 2007; Cross, 2019; Kimbell, 2011). The design methods movement concentrated on the study of a design methodology (or process), which can be traced back to the 1962 Conference on Design Methods. Championed by scholars such as Alexander (1962), Archer (1968), Jones (1992), Paul (1984), and Beitz (1984), this approach found its way into disciplines such as architecture, planning, engineering, and industrial design (Cross, 1993). These scholars were primarily interested in investigating and systemizing processes and methods for problem-solving and supporting creative processes that address design problems (Jones & Thornley, 1963).

Design studies scholars such as Cross (1982) pointed out that “designerly ways of knowing” are embedded in the process and products of designing, which generate responses to ill-defined or “wicked” problems. Studies on the cognitive design approach to problem-solving led to a generalized “design thinking” concept, further elaborated as “an intellectual approach to problem framing and problem-solving” (Kimbell, 2009, p.4). The term “design thinking” appeared as a title in Rowe’s (1987) book examining design process and form in architecture and urban planning as a way to describe designers’ inquiry and how they operate and reason. DT has attracted many scholars since the initial Design Thinking Research Symposia series meeting in Delft in 1991 (Cross, 2018), while in the USA, DT by design consultants from IDEO and business disciplines gained commercial interest (Brown, 2008; Martin, 2009).

The rapid spread of design in education is also evident in business schools and distance learning training. For instance, since 2005, the Hasso Plattner Institute of Design at Stanford University in California (d.school) and Potsdam, Germany, has been training DT students from disciplines such as engineering and business, and external participants from the private and public sectors to innovate products and services (Meinel & Leifelr, 2011). This training is based on the belief that “design thinking is a catalyst for innovation and bringing new things into the World” (p.xiii).

The worldwide adoption of design has led to several design methodologies. Two of them are popular with practitioners, which are the Double Diamond developed by the Design Council (2005) and the Stanford d.school’s approach (2011). Developed in 2005, the Double Diamond represents four stages central to the design process: discover, define, develop, and deliver (Figure 1). The first diamond represents the understanding of the problem, while the second represents the generation of solutions. Both are iterative processes of convergent and divergent thinking (Design Council, 2007). The d.school’s DT framework consists of five stages: empathize, define, ideate, prototype, and test (Hasso Platner d.School, 2011). While there may be differences, design methodologies worldwide share two common “spaces of work:” the problem space (noticing, understanding, and (re)defining a problem primarily through qualitative research) and the solution space (ideating and testing solutions) (Dorst, 2019; Dorst & Cross, 2001).

Double diamond model

Source: Design Council (2019)

Increasingly, designers have involved users in design processes building on participatory design processes (Simonse & Robertson, 2013) and collaborative activities known as co-creation and co-design (Sanders & Stappers, 2008). These collective and collaborative activities advocate for involving actors such as -potential- users and other experts who are not typically engaged in design processes (Mattelmäki & Sleeswijk Visser, 2011). The participatory design approach emerged in the 1970s as a design process in which users act as partners providing their experience and knowledge (Mattelmäki & Sleeswijk Visser, 2011; Sanders & Stappers, 2008; Simonse & Robertson, 2013). Within this participatory approach, the concepts of co-creation as an ‘act of collective creativity’ and co-design as collective creativity along the design process (Sanders & Stappers, 2008, p.6) have become part of the shared language about creative activities in organizations (Mattelmäki & Sleeswijk Visser, 2011).

The conceptual richness of the design discipline implies specific ways of knowing are embedded in the processes and products, as well as cognitive approaches to problem-solving and innovation. This has led to other avenues of inquiry, such as human-centered design, user-centered design, participatory design, and co-creation. This stresses the importance of focusing on user experiences and involving multiple actors in the process for collective creativity.

In contrast to the design discipline, the policy sciences approach to design is more multifaceted and has experienced ebbs and flows over the past 50 years. In his review of the discipline, Howlett (2014) argues that policy design is situated in “the roots of the contemporary policy sciences … as both a process and an outcome” (p.190). Here, “design” is connected to policy processes (systematic application of knowledge to define policy goals, adopting instruments or courses of action to realize those goals) and to policy outputs, combining instruments’ choices (Howlett & Mukherjee, 2018; Howlett, 2019). Although policy design is often associated with a specific form of policy formulation, it also involves the deliberate and conscious attempt to define policy goals and instrumentally connect them to tools expected to realize those objectives (Gilabert & Lawford-Smith, 2012; Majone, 1975; May, 2003).

Howlett and Mukherjee (2018) argue that policy designers must be aware of three aspects of policymaking, namely the design process, instrument choices, and policy outputs. Howlett (2014) also states that the contextual orientation is also central. Clarke and Craft (2018) point to political constraints and influences, policy capacity levels, policy style type, and policy mixes as dominant contextual factors in the discipline. Similarly, Peters (2018) states that policy design is more specific than general policymaking because it is “a conscious effort to create a template that can guide any intervention” (p.16).

Howlett & Lejano (2013) and Howlett (2014) differentiate the “old” and “new” periods of policy design in the policy sciences, with the former emerging in the 1970s and flourishing in the 1980s and early 1990s. Initially, there was interest in differentiating implementation and formulation following an interest in instrument types and choices. Central was “systematically develop[ing] efficient and effective policies through the application of knowledge about policy means gained from experience, and reason” that would lead to policy desired goals (Howlett 2014, p.188). Here, efforts were made to categorize different types of policy instruments and policy choices. The best known is Hood’s (1986) “NATO” policy instrument taxonomy. Instrument choice depended on various factors, such as the nature of the policy problem, political feasibility, and the government’s capacity to implement the chosen tools. The NATO classification of tools includes nodality (i.e., information based), authority (i.e., regulatory), treasure (i.e., fiscal), and organization (i.e., direct action by the government). Hood also distinguished between policy tools designed to effect change (effectors) in a policy environment and those designed to detect changes (detectors). Another critical early policy design contribution was Schneider and Ingram’s (1993) article “Social Construction of Target Populations: Implications for Politics and Policy,” which introduced the concept of the social construction of target populations and advanced the policy design literature. Here, the idea of policy instrument choice was influenced by the social construction and power of target populations, often reinforced by feedback mechanisms.

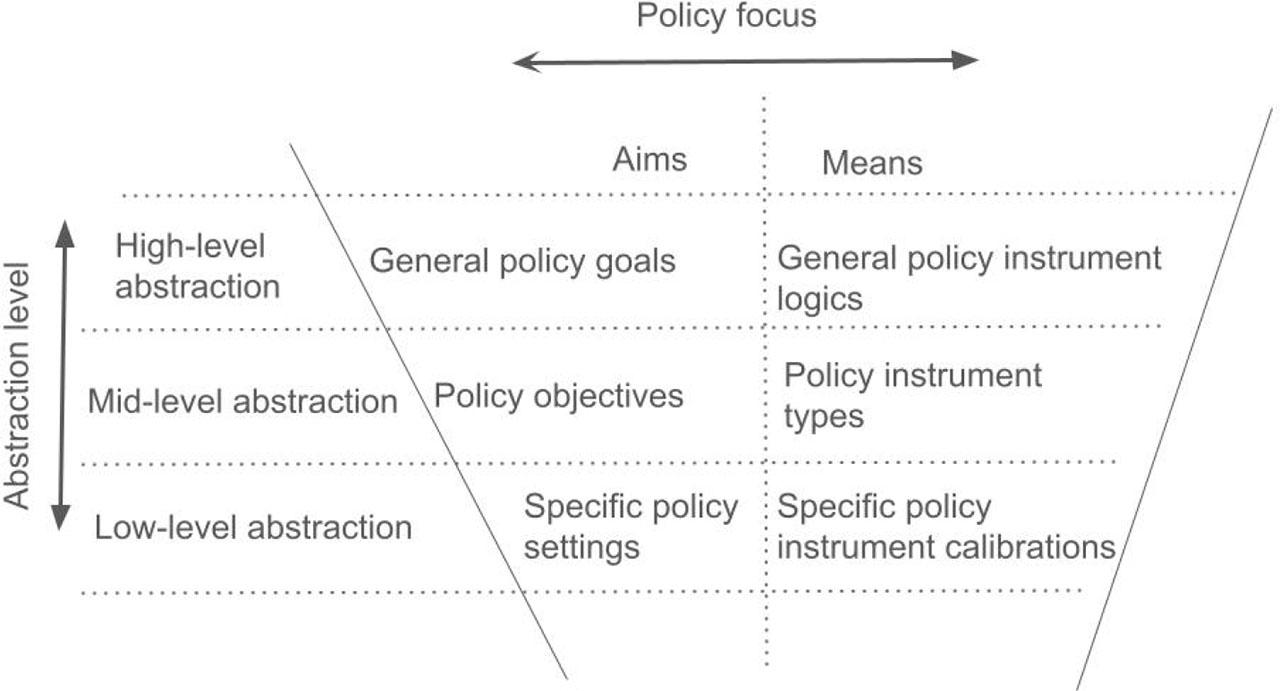

The resurgence of “new” policy design studies since the early 2000s has led to some noteworthy contributions. The first is the notion of the policy mix. Whereas the old policy design focused on single instruments, the cross-sectoral and long-term nature of policymaking reveals the simultaneous interaction of policy goals and their instruments. Often, a policy’s various elements (goals, instruments, and calibrations) can be seen as a policy mix that develops in fits and starts over time (Rayner et al., 2017). This hierarchy of policy elements in the policy mix is illustrated in Figure 2. This has led to investigations of how policy mixes are often inconsistent, incongruent, or inconsistent, leading them to evolve through different processes such as layering, drift, or conversion, often leading to suboptimal outcomes (see Rayner and Howlett, 2009).

Policy elements in the policy mix

Source: Cashore and Howlett (2007) and Haelg et al. (2019)

The role of causal mechanisms in policy design scholarship is a new research area. Capano et al. (2018) argue that a mechanistic approach to policy design can open the “black box” of policy behavior. Specifically, this involves conceptualizing activated mechanisms that alter the behavior of individuals and groups, and those mechanisms, such as learning, diffusion, and social trust, that produce structural changes. Haelg et al. (2019) reiterate Howlett’s point about the role of actors in policy design, in particular, the importance of policy advice and policy capacity. Siddiki and Curley’s recent (2022) survey of the policy design literature also refers to the process and outputs outlined by Howlett (2014) as policy designing. However, they highlight a second approach, which they label “policy design as policy content,” which examines “what information is conveyed within public policy” (p.122). Specifically, “Institutional Grammar” was first developed by Crawford and Ostrom (1995), but adapted to help identify specific design elements within policy statements, such as the targets (attributes), the prescriptive operators (deontic), the actions or outcomes (aim), the circumstances (conditions), and the consequences (or else). Researchers can better understand policy instruments’ underlying logic and intended functions by deconstructing policy statements into these components. This also allows researchers to assess the coherence and consistency of policy designs. This analysis can reveal potential conflicts, duplications, or synergies among policy instruments and identify gaps or ambiguities in the institutional arrangements.

Recently, concepts such as DT, co-design, and co-production have begun to appear in the policy sciences and public management literature (e.g., Howlett & Mukherjee, 2018; Clark & Craft, 2019; Howlett, 2020; van Buuren et al., 2020), and policy concepts have also become a topic of interest in design literature. For instance, responding to the policy science’s interest in the design practice, Policy and Politics published a special issue in 2020, “Policy-making as Designing: The Added Value of Design Thinking for Public Administration and Public Policy.” In the introductory article, van Buuren et al. (2020), reflect on the influence of Simon’s (1969) rational design and the emergence of perspectives such as “design as optimization,” “design as exploration,” and “design as co-creation.” Within these perspectives of design, the notable issue contributors discuss the co-design and DT approaches to address public and policy themes (Hermus, Van Buuren & Bekkers, 2020; Howlett, 2020; Lewis et al., 2020; Olejniczak, Borkowska-Waszak, Domaradzka-Widła & Park, 2020).

From the design perspective, Bason’s (2014) edited volume Design for Policy frames emerging applications of design disciplines for public services and public policy innovation. The volume examines the collaborative experiences of policy and design practitioners worldwide through approaches such as co-creation, co-design, participatory design, and the (re)design of services. The design for policy (4) scholarship originates from applying service design in the public sector, adopting user-centered design, participatory design, and co-design to address “from high-level (macro) ‘policy design’ to the more tangible ‘service design’ of human system interactions, and to ‘participation design’ to help drive citizen and community engagement.” (p.38)

Bason (2014) identifies three key “design for policy” components. First, public problems and their root causes are understood through a design research lens (e.g., ethnographic, qualitative, user-centered research), prototyping, and data visualization. Second, facilitated collaboration that enables dialog and mutual understanding among actors (e.g., policymakers, lobby groups, external experts, and citizens) allows for ownership of solutions through the above design methods. Finally, design gives form and shape to policy by creating tangible artifacts that people can engage with (e.g., graphics, templates, maps, products) and creating experiences for products and services.

While some scholars highlight the current challenges of applying design disciplines in public issues (Clarke and Craft, 2019; Howlett, 2020; Lewis, 2020; Siddiki & Curley, 2022), others in the policy sciences field also recognize design’s potential to complement current policy design approaches and contribute to the development of the field (Blomkamp, 2018; Van buuren, et.al., 2020).

However, within the current intersection of design and policy perspectives, we argue that there are more than semantic differences in the use of concepts. For instance, when policy scholars refer to the design discipline in the public sector as “design thinking,” “design for policy,” or “co-design” (Blomkamp, 2018; Clarke and Craft, 2019; Howlett, 2020; van Buuren et al., 2020). Also, new hybrid roles are appearing in the public service. For example, the Policy Lab and the user-centered policy design teams, which are located in the UK Cabinet Office, have created “policy designer” positions that “use practical design skills to improve the Policy Lab’s suite of tools, techniques, and communications materials” (Whicher & Swiatek, 2022, p.473).

We identify policy and design-related information by examining Google (5) search engine (GSE) results from the diverse “Policy * Design” field. Despite some concerns, this method appropriately addresses our research question (Rogers, 2013, pp. 99–104). The GSE was selected because it is the most popular search engine worldwide (StatCounter Global Stats, 2019). Second, it is an essential source of all information accessible to practitioners and academics. Third, it indexes sources that would not appear in academic databases, but provide social significance to the concepts (e.g., the book, Design for Policy).

Digital methods and issue mapping are used together for researching and visualizing a particular topic (issue) on the World Wide Web. Central to our analysis of the Policy * Design field were the results of GSE, which ranks the relevance of a data source by combining “in link with click count and freshness” (6) (Rogers, 2013, p.99). Table 1 summarizes the steps for collecting, processing, visualizing, and analyzing data described below.

Summary of the data collection and data processing processes.

| Stage | Step | Google search engine (GSE) results | Action | Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | 1. Search query: “design*policy” “policy*design” to identify Policy * Design concepts | 20 (10 per query) | Identify concepts using the words “design” and “policy” | Four concepts were identified as common to both queries: policy design, design for policy, design policy, design in policy |

| 2. Search queries: “Policy Design,” “Design for Policy,” “Design Policy,” “Design in Policy” | 120 (10 per concept in three countries) | Obtain GSE results per query in three countries: Italy, Colombia, and the USA | Four concepts of GSE results were collected in a database for further analysis, classified by query, article title, article URL, and article description | |

| Data processing | 1. Categorize results | 120 | Read each URL and categorize GSE results manually in the database | 120 GSE results verified, categorized, and filtered:

|

| 2. Reclassify results under each query | 117 | Read GSE results in detail and move them to the list of another query due to better fitting | 36 results moved to the list of results of other queries | |

| Data visualization | Visualize results | 117 | Insert the reclassified results in a data visualization tool | Presents the four concepts categorization in the country, type of actor, and name of the key actor |

| Data analysis | Analyze the contents per concept | 117 | Examine the descriptions of each concept according to the key actors (higher number of GSE results) | Description of each concept elaborated from the content examined by the key actors |

Between July and October 2022, we collected data from the Policy * Design concepts by identifying combinations of the words policy and design and then searching these combinations in GSE. Identifying the common combinations in GSE consisted of searching the two queries “design*policy” and “policy * design” separately. (7) The first 10 results of each query (equivalent to the first page of results frequently visited by users (8)) were examined by searching which combination of the words design and policy was used in the content of each result. This first step identified four common concepts emerging from the two queries’ results: “policy design,” “design for policy,” “design in policy,” and “design policy.” This was followed by searching policy * design terms through a Google Scraper (GS) tool that returned google.com results in a file, avoiding cookies and reducing the tracing of our navigation history and country.

The GS tool output collects online data of each result, such as title, uniform resource locator (URL), and description, in the form of unstructured text. Moreover, for each result, we scanned the online document (e.g., blog, website, academic article). The GS tool was used for this search in English in three countries, Colombia and Italy (not native English-speaking countries), and the USA, due to the physical location of the researchers, to triangulate data and decrease residual country tracing. In total, 120 results (10 results for four queries in three countries) were collected in a database classified by query, article title, article URL, and article description for their further analysis.

Processing of the 120 results in the database included categorizing and reclassifying the results under each query group. The categorization of results in the database was developed by examining each URL’s content. This examination aided in verifying, categorizing, and filtering the results. For instance, the verification entailed inquiring whether the searched query effectively corresponds to the one(s) within the URL’s content. Afterward, the content categorization implied further classification of each result according to the type of content (e.g., article, book chapter, blog), actor name (e.g., person’s or organization’s name), type of actor (e.g., researcher, practitioner, public sector agency), and location of the actor. These categories are presented in Tables 2–5. Simultaneously, the verification step allowed us to find and remove the results irrelevant to the search from the database. Among the 120 GSE results, we marked two as “Not applicable” (N/A) due to their lack of connection to the topic of interest (e.g., company’s policy terms) and one as “Not found online” (N/F), narrowing the results to 117. (9)

Distribution of countries.

| Country | Location (code) | Total |

|---|---|---|

| Austria | AUT | 1 |

| Canada | CAN | 6 |

| Croatia | HRV | 1 |

| Denmark | DNK | 28 |

| Germany | DEU | 1 |

| India | IND | 2 |

| Italy | ITA | 19 |

| The Netherlands | NLD | 3 |

| UK | GBR | 23 |

| USA | USA | 26 |

| Varied | Var | 4 |

| European Union | EU | 3 |

| Total | 117 |

Distribution of concepts.

| Query validation | Total |

|---|---|

| Policy design | 53 |

| Design for policy | 36 |

| Design in policy | 15 |

| Design policy | 13 |

| N/F | 1 |

| N/A | 2 |

| Total | 120 |

Distribution of the content type.

| Content type | Total |

|---|---|

| Journal article | 17 |

| Blog/post | 29 |

| Book/chapter | 44 |

| Course/program | 14 |

| Definition | 1 |

| Event/workshop | 7 |

| Group/network | 2 |

| Policy | 1 |

| Report | 1 |

| Toolbox | 1 |

| Total | 117 |

Distribution of author type.

| Author type | Total | |

|---|---|---|

| Individuals | Academic researchers | 40 |

| Civil servants | 8 | |

| Practitioners | 26 | |

| Organizations | EU-funded consortium | 1 |

| Nonprofit organizations | 15 | |

| Public sector agencies | 4 | |

| Research groups | 8 | |

| Universities | 14 | |

| Other entities | 1 | |

| Total | 117 |

Finally, the categorized queries in the database were inputted into open-source data visualization tools, allowing us to visually represent the results and analyze key information to provide meaning to each of the concepts (country, type of actor, and type of content). The visualization results are later presented in Figure 3.

“Policy * Design” issue mapping visualization by concepts, actors, and location

In this section, we provide a descriptive overview of data processing and then content analysis of the results building on data visualization.

From the GSE search results, the distribution by country of origin, types of concepts, content, and authorship are highlighted in Tables 2–5. First, Denmark, the USA, and the UK were the most prevalent sources for Policy * Design information (Table 2), coherent with the language of the query (English), the widespread use of design in the public sector at the UK and Denmark, and the relevance of key actors. As expected, the concept of “policy design” was the most prevalent, followed by “design for policy” (Table 3). Consistent with our argument regarding the importance of practitioner-oriented Policy * Design sources, blogs, courses, and workshops were as crucial as scholarly peer-reviewed journals, books, or chapters, typically found in edited volumes (Table 4). Nearly two-thirds of the content was authored by individuals, in particular researchers. Practitioners were also prevalent. Nonprofit organizations and universities were the two main organizational contributors (Table 5).

The issue mapping and data visualization illustrate “Policy * Design” landscape concepts highlighting authors, their location, and the type of information available. In this section, we focus on characterizing the four concepts of “policy design,” “design for policy,” “design in policy,” and “design policy” through the key actors and their related GSE results (URL links). We refer to key actors as those with higher results for each concept. Figure 3 visualizes the four Policy * Design categories (center), key actors, author types, and their locations. The inner circle connecting lines reflects the findings presented in Table 3 that policy design was the most dominant of the Policy * Design categories that emerged from GSE scraping, followed by design for policy, design in policy, and design policy. The colored circles represent the specific authors (Table 6) associated with the respective four Policy * Design approaches. The most prevalent actors are followed by a bigger colored circle, and we describe their related content for each Policy * Design category in the following paragraphs.

Summary of Policy * Design characteristics.

| Policy Design | Design for Policy | Design in Policy | Design Policy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key actors | B. Guy Peters (co-author Nenad Rava), Michael Howlett (co-authors Gilberto Capano and Ishani Mukherjee), and the Harvard Kennedy School | Christian Bason and Design for Policy (book) authors | Design Council and Policy Lab – Vasant Chari and Andrea Siodmok | Design Policy Lab – professors Marzia Mortati and Stefano Maffei (Design Department at Politecnico di Milano) and UNESCO |

| Geographic location of key actors | Canada, USA, Italy, and Singapore | Denmark/Europe and worldwide | UK | Italy – Iceland/Europe |

| Orientation | Academic | Practitioner | Practitioner | Academic |

| Key messages | Design is focused on both the process and outputs with attention to political contexts | Design approaches to address public problems and innovate in public policy – particularly public services | Design methods applied with other methods in policymaking | Policies for broader application of design in the economy |

| Main theme | Design process and product (policy) | Design process and product (i.e., services) | Design in process to create policies | Design included in policies |

| Resources | Articles (for purchase) and open access | Book (for purchase) | Open-access blogs | Open-access reports and articles |

Tkey actors were relevant to the concept of policy design: B. Guy Peters (USA) (who also co-authored with Nenad Rava), Michael Howlett (Canada) (who also co-authored with Gilberto Capano [Italy], and Ishani Mukherjee [Singapore]), and the Harvard Kennedy School. Peters and Howlett’s contributions are described above in the literature. Other academic authors, such as Van Geet et al. (2020), elaborated on Howlett’s policy mix framework, while Cairney considered the role of other policy theories in policy design. Except for Peters and Rava’s 2018 workshop paper, all were peer reviewed and not open access. Peter and Rava provide an overview of how policy design engages with overlapping concepts from different disciplinary perspectives and how it changes the traditional policy design literature. In addition to academic scholarships, there were academic websites promoting policy design programs. Knight’s 2022 blog “Public Policy Design” is one of two practitioner-based entries. In it, he outlines five areas of policy design work underway in the UK civil service: advocacy and embedding design, design community and events, design training, future design workforce, and future design practice. The 2023 blog “Public Policy Design” provides updates following up on Knight’s blog.

The key author for the design for policy concept is Christian Bason, the editor of the well-cited (10) book Design for Policy (Bason, 2014). Bason is currently the CEO of the Danish Design Center and the former Head of MindLab (one of the first public sector innovation units in Europe).

Design for Policy (11) outlines the emerging design approaches (usually collaborative) to address public problems and innovate in public policy. It collects the experiences and knowledge from design practitioners, public managers, and academics worldwide (Bason, 2016). Accordingly, design for policy originates from using service design in the public sector. It “evolved from the notions of user-centered design, participatory design, and co-design” and regards the use of “design as an approach to policy and service innovation in the public sector” (Bason, 2014, p.3).

Design approaches in the public sector attempt to address “from high-level (macro) ‘policy design’ to the more tangible ‘service design’ of human-system interactions, and to ‘participation design’ to help drive citizen and community engagement” (Bason- trends- p.38). Yet, “the most convincing current examples of the potential of design for public sector innovation seem to be in the service design category” (Bason, 2014, p.38).

According to Bason (2014), the potential contribution of the design for policy field centers on three themes. First, the problem is understanding through design (e.g., ethnographic and user-centered research) and testing (e.g., prototyping). A second theme is an emphasis on facilitating collaborative design (e.g., participatory design, co-design, and co-creation), which suggests collaborating with multiple policy actors in the design processes by involving policymakers, interest groups, experts, and end-users in creating solutions. Finally, visual representations help form and shape policy in practice by creating tangible artifacts, user experiences, service processes, and products that people can engage in. These three themes are exemplified throughout the book through various authors’ experiences in the public sector.

The academic chapter “Chapter 13 – Design for Policy” by Rudkin and Rancati (2020) describes the development of the EU Policy Lab. In it, they discuss similar themes raised by Bason, specifically the need for exploratory sessions, “state-of-the-art research,” and stakeholder/user/citizen workshops. Leoni’s open access (2020) conference paper “Design for policy in data for policy practices. Exploring potential convergences for policy innovation” considers design for policy approaches in public sector reform, consistent with Bason’s work. Junginger’s 2013 open-access conference paper, and chapter in Design for Policy (Junginger, 2014, p. 57–69), provides a scholarly critique of the divide between the realm of policymaking and the realm of designing. She argues that designers have been engaged in the implementation stage of the policy process when there should be all stages of the policy process, “policy-making as designing.” The remainder of the paper focuses on design and public sector reform.

The Centre for Public Impact, a think tank, published an open-access, non-peer-reviewed paper titled “Design for Policy.” In it, they outline the three major steps in the design-for-policy process: understanding the human experience, generating ideas and solution space, and developing prototypes. Common tools include shadowing, bodystorming, and prototyping. The Design Council’s blog “Using Design to Improve Policy” outlines the design approaches used by the UK Civil Service’s Policy Lab via a five-minute video.

The key actors for this concept are the Design Council and the Policy Lab located in the UK and the design practitioners Vasant Chari, former Head of the Lab, and Andrea Siodmok, former Head of the Design Council and the UK Policy Lab. According to these authors, design in policy refers to applying an adapted design by understanding economics, public policy, organizational development, and the role of systems leadership practice in policymaking “alongside ethnography, digital and data science” (Siodmok, 2020). For Siodmok, applying design in policy/policymaking requires “unpack[ing] long-held assumptions about what design [is] and how it work[s] in practice.”

Design is a “highly useful tool for building government around the needs of citizens, not bureaucracies” and helps the public sector to innovate. From the application of service design in the UK central government, design has emerged as an approach to policy as one of the new methods trialed through the Policy Lab (Design Council, 2014). According to Chari (2018) and Siodmok (2015), designers at the Policy Lab learn about public policy and other skills to bring multiple practices together while learning from each other. By doing so, they provide policymakers with important design tools such as ethnographically informed research and prototyping. For example, the Policy Lab has applied a speculative design for regulatory environments and developed codesigned scenarios that are critical during policy formation (e.g., Green Paper) (Siodmok, 2020).

The key actors for this concept are the Design Policy Lab from the Design Department at Politecnico di Milano in Italy and UNESCO’s page featuring Iceland’s approach to design policy. Professors Marzia Mortati (former part of the lab) and Stefano Maffei are prominent design policy authors at the Design Policy Lab. They state that design policy refers to a process in which governments develop policies to support the design sector and its use in the country, accelerating the inclusion of design in innovation policies. Marjanovic’s accessible 2003 conference proceedings paper also echoes this perspective.

Documents published by the Design Policy Lab, such as the Design Policy Beacon and DeEp -Design in European Policy, and Mortati and Maffei’s (2018) article support Raulik-Murphy’s definition of design policy, namely “the process by which governments translate their political vision into programmes and actions in order to develop national design resources and encourage their effective use in the country” (2009, p.7). Furthermore, design policy “aims to accelerate the use and acceptance of design in innovation policies” (Design Policy Lab, n.d.) by considering “design as a driver of socio-economic growth” (Mortati & Maffei, 2018).

Along this line, Icelandic design policy aims to increase the importance of design in the Icelandic economy. The goal is to strengthen the competitive position of Icelandic companies, increase value creation and quality of life (UNESCO 2020). To achieve this goal, their design policy is based on three “key pillars,” namely providing education and knowledge at all levels of organizations; fostering working environments and support networks to strengthen collaboration, increase efficiency, simplifying processes and improving regulation; and finally, “awareness raising,” which promotes the understanding of the value of design and its dissemination through presentations and exhibitions.

A synthesis of our findings is presented in Table 6. When searching the term “policy and design” on Google, content from the mainly academic policy design field was the most frequently found in our searches. The major type of content is scholarly articles or books, of which many in our search were behind journal paywalls. Fortunately, many scholarly contributions are becoming more readily available on academic-oriented sites such as Academia.edu, Google Scholar, and Research Gate. Policy design in these documents regards a process and a product. Design for Policy and Design in Policy were the most similar; while one collects experiences worldwide, the latter refers particularly to the UK public sector reform. Design for Policy was heavily influenced by the book edited by Christian Bason, and him as a design practitioner with a growing academic following. Regardless of the content, both approaches presented a normative perspective, namely that design approaches ought to be part of policy design content and processes.

Like Design for Policy and Design in Policy, Design Policy was also influenced by the design discipline. All three described various design-based discipline tools (e.g., prototyping, experimenting) and collaborative approaches (e.g., co-design and co-creation). However, Design Policy had little to no focus on designing policies, but rather on the broader role design discipline would have in the economy. Public servant practitioners who discussed Policy * Design concepts in blogs used Policy Design, Design for Policy, and Design in Policy terms interchangeably.

Design as a concept represents a source of confusion because it can adopt various meanings (e.g., a design, to design). It applies multiple approaches (e.g., co-design, user-centered design) and methodologies as a discipline. Adding the concept of policy, which also has different disciplinary traditions, only compounds the complexity. In response, we call for developing a “Policy * Design” field by clarifying the meanings of various concepts, and, thus, being able to use them consistently and communicate unambiguous messages.

In this direction, we critically examined the terrain of the Policy * Design field, in which the practices of design and policy meet. An online search, through issue mapping and digital methods, allowed us to encounter a shared space for academia and practitioners’ knowledge and know-how. GSE scraping produced four possible Policy * Design combinations: policy design, design for policy, design in policy, and design policy. With it, we identified the key actors, their locations, roles, and online information types and content. Our research examined the descriptions of these concepts by key actors.

Building on the results examined in the previous sections, we propose the following four working definitions for the Policy * Design landscape:

Policy design is the deliberate and conscious attempt to define policy goals and connect them to instruments or tools expected to realize those objectives. It requires understanding the linkages and causal mechanisms between policy tools and desired outcomes, as well as the specific contextual factors that can influence policy effectiveness. It also involves the application of knowledge about policy means gained from experience and reason to the development and adoption of courses of action with particular attention to target audiences.

Design for policy frames the emerging collaborative design approaches in the public sector to address public problems along policy processes, from macro-level policy to, more frequent, micro-level public service design, also supporting citizen and community engagement in policy. In this regard, the promise of design for policy concerns the use of methods for addressing public problems through design research, prototyping, and data visualization; facilitating collaboration, enabling communication among actors and ownership along design processes; and giving shape to policy through design representations (artifacts) that people can engage with.

Design in policy derives from the adaptation and adoption of design as one of the policy approaches. It is about design meeting policymaking along with various practices (e.g., economics and public policy) and methods (e.g., ethnography and data science), brought together to develop policies. In this context, design in policy also regards mutual learning among the various practitioners and providing policymakers useful design tools.

Design policy is a process in which governments develop policies to support the design sector and their use in the country, accelerating the integration of design in innovation policies. These policies consider design as relevant for the economy and suggest strategies such as fostering the study of design and the work of designers and raising awareness about design.

Future research should more rigorously validate the four Policy * Design concepts we identified to improve upon the proposed definitions. The low cost and access to the data mean that future digital analyses using online tools such as GS will readily lead to comparative and longitudinal analyses of the query results. Alternatively, researchers could conduct key informant interviews or focus groups with researchers or practitioners to further interrogate the Policy * Design landscape. This strategy would be particularly beneficial for non-English-speaking policy communities.

When using Google Search Engine, the quotation mark ( “ ” ) and star (*) operators are used, respectively, for searching for results that mention a specific word or phrase, and as a wildcard matching any word or phrase (Hardwick, 2024). Thus, “Policy * Design” reflects the search of multiple combinations of the words policy and design.

We use the Google Search Engine Scraper tool “Search Engine Scraper” from the Digital Methods Initiative available at https://digitalmethods.net/

Design is a word with multiple levels of meaning. Etymologically, the design has its origins in the 1580s, indicating “a scheme or plan in the mind,” from the French desseign, desseing “purpose, project, design.” In the 1630s’ art, it referred to “a drawing, especially an outline.” The verb design comes from the Latin designare “to make, shape” and from the Italian disegnare “to contrive, plot, intend, [...] to draw, paint, embroider,” which originated in the 14th and 16th centuries, respectively (Online Etymology Dictionary, n.d). Heskett (2005) illustrates this using a nonsensical sentence: “Design is to design a design to produce a design” (p.3). Breaking it into pieces, Heskett explains that design is: a noun (Design), meaning the concept of a field or discipline (e.g., graphic design, product/industrial design, service design); a verb (to design), suggesting an action or process, a noun (a design) referring to a concept or proposal, and again a noun (to produce a design), meaning a final output or product.

Lately, in the design discipline, the conjunction “for” has been used to differentiate the traditional design practices (e.g., product design, interior design) from the emerging practices in which design is applied to new contexts and purposes (Sanders and Stappers, 2008). Following this trend, the Routledge publisher edited since 2007 a book series on what they call “Design for Social Responsibility.” The book “Design for Policy” is part of this collection, which has titles such as “Design for Behaviour Change” and “Design for Services.” This illustrates “the design disciplines’ focus on designing for a purpose” (Sanders and Stappers, 2008, p.10–11).

Google Search Engine “analyze[s] the content to assess whether it contains information that might be relevant to what you are looking for.” The relevance derives from retrieving the search query keywords in the content, content interaction data, and additional content related to the key word (Google, n.d.).

GSE considers in-link count (number of links found in one page into another site and the content of the link) and the clicks of people in those links in previous searches (Rogers, 2013).

In these queries, the quotation marks imply the request for the exact match of the words (not synonyms or equivalents) and the asterisk (*) acts as a wildcard to get a variety of combinations between the two words (e.g., replacing the asterisk with connector or preposition).

Users often choose only from the first results page or often look only at the first page of their search results (Schultheiß,, Sünkler & Lewandowski, D, 2018).

The data processing also involved reclassifying 36 of the results because the same actor and content appeared under multiple concepts’ query results. By doing so, we eliminated overlapping results. For example, the book Design for Policy, edited by Christian Bason, appeared multiple times under the results for the queries Design for Policy (19 times) and Design Policy (twice). The two design policy results referred to his book and were moved to the Design for Policy category.

386 citations in Google Scholar by March 2024.

Lately, in the design discipline, the conjunction “for” has been used to differentiate the traditional design practices (e.g., product design, interior design, communication design) from the emerging practices in which design is applied to new contexts and purposes (Sanders and Stappers, 2008). Following this trend, the Routledge publisher edited since 2007 a book series on what they call “Design for Social Responsibility” (https://www.routledge.com/Design-for-Social-Responsibility/book-series/DSR). The book Design for Policy is part of this collection, which has titles such as “Design for Behaviour Change,” “Design for Sustainability,” and “Design for Services.” This illustrates “the design disciplines’ focus on designing for a purpose” (Sanders and Stappers, 2008, p.8).