Cultural activity, within the meaning of the Act of 25 October 1991 on Organizing and Conducting Cultural Activities, indicates that it consists in creating, disseminating, and protecting culture. The organizational forms of cultural activity are in particular: theatres, operas, operettas, philharmonics, orchestras, film institutions, cinemas, museums, libraries, cultural centres, artistic centres, art galleries, and research and documentation centres in various fields of culture. It is worth noting that according to the above-mentioned Act, the state exercises patronage over cultural activities.

Although cultural activity is important for every community, whether local, regional or national, it is rarely analysed in the literature on the subject from the quantitative side. This is due to many reasons, the most important of which is its intangible value for the recipient, expressed rather in terms of emotions and feelings. Another problem is the comparability of different units conducting cultural activities, in different areas or specializations. The availability of data and its completeness are also important.

Therefore, the National Institute of Museums (NIM), a unit subordinate to the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage (MCNH), is implementing an ambitious project called ‘Museometer’, which

...aims to develop an integrated system for parameterization and evaluation of the efficiency of museums and other cultural institutions operating in the field of memory policy. As a consequence, on the basis of the algorithm, an IT tool will be created for the objective calculation of subsidies for these institutions. Legislative recommendations will also be prepared for the implementation of the parameterization and efficiency assessment system…(National Institute of Museums 2024) of museums in Poland.

Due to the lack of appropriate research on the efficiency of museums in Poland, which will be discussed later in the article, and the willingness to provide scientific support during the implementation of the project by the NIM, it was decided that the problem of measuring the efficiency of museums in Poland should be addressed. The aim of this paper is therefore, to assess the efficiency of museums in Poland, along with the analysis of determinants affecting this efficiency. These are preliminary studies on this topic, which may help to develop a proposal for the aforementioned algorithm for assessing the efficiency of museums. The presented results may also be useful for the participants of the Second Congress of Polish Museologists, which is planned for November 2026. The MCNH entrusted the NIM with the coordination of work, related to the preparation of the congress, which confirms the important role of this institution in this sphere and its activities.

The research process is designed to answer the following research questions:

Q1: What studies of the efficiency of museums have been conducted so far and what research gaps remain to be filled? Q2: What sources of data on museums and publications are available in Poland? Q3: What is the level of efficiency of museums in Poland, and are there differences in efficiency between groups of museums of a certain type? Q4: What environmental factors affect the level of efficiency of museums?

The added value of the article is therefore the measurement of the efficiency of museums and the estimation of the impact of potential determinants on the level of this efficiency using the DEA (Data Envelopment Analysis) methodology. Research of this type has not been carried out in the literature on the subject in relation to Polish museums so far. Due to the deficiencies and errors in the collected data, it was necessary to limit the analysis of the efficiency of only selected statutory activities of museums – for details, see the methodological part of the work.

A well-targeted literature review was used to answer the first and, in part, the second research question.

The research topics on museums in Poland are very diverse, but almost entirely focused on qualitative and descriptive issues such as: characteristics of their activities (Giergiel 2023), legal issues (Drela 2015), sociological matters (Nieroba 2014), management (Lewandowski 2006), promotion and marketing (Nawrocka & Zaprucka 2022), impact on tourism (Rosicka 2017) or the local economy (Obłąkowska-Kubiak 2018), impact on education (Rogozińska 2020), etc. Not counting industry reports issued by Statistics Poland (SP) and Statistical Office in Kraków (2024) and NIM (National Institute of Museums 2023), there is a lack of scientific publications in Poland that analytically, based on quantitative data, examine the way museums operate, not to mention measuring the efficiency of these cultural institutions.

Much more empirical research, based on quantitative data, can be found in foreign literature. Brzezicki’s (2024) review of research on the efficiency of museums around the world shows that the vast majority of them were conducted using the nonparametric DEA method (Taheri & Ansari 2013; Del Barrio-Tellado et al. 2023), and a few using the parametric SFA (Stochastic Frontier Analysis) method (Xie 2019; Taniguchi 2021). Other analytical methods have been used very rarely in this regard (Camarero et al. 2015; Guccio et al. 2020b).

The research concerned either the efficiency of individual museums in a given research sample (museums from a given region or country) or, much less frequently, the efficiency of regions in the field of museum activity. Researchers used a variety of DEA models, ranging from the simplest ones, such as CCR (1) (Taheri & Ansari 2013), BCC (2) (Šebová 2018), to more advanced ones, such as SBM (3) (Kim & Chung 2019), Network SBM (Haruna et al. 2012), or Network Dynamic SBM (Del Barrio-Tellado et al. 2023). However, most of the research was conducted using simpler models.

In the literature on the subject, one can also find studies in which the authors used a two-stage analysis (Plaček et al. 2017; Guccio et al. 2020a). It consists in estimating the efficiency of the surveyed entities in the first stage, and in the second stage, the impact of environmental variables on efficiency is determined. In addition, Mälmquist index were also used to measure changes in productivity and efficiency over time of the analysed museums (del Barrio-Tellado & Herrero-Prieto 2022) or regions (Del Barrio-Tellado et al. 2023).

Studies on the efficiency of museums have been conducted in many countries (Brzezicki 2024), among others China (Zhao et al. 2024), the Czech Republic (Plaček et al. 2017), Spain (Del Barrio-Tellado et al. 2023), Iran (Taheri & Ansari 2013), Japan (Haruna et al. 2012), Korea (Kim & Chung 2019), Portugal (Carvalho et al. 2014), Slovakia (Šebová 2018), and Italy (Guccio et al. 2020a).

The efficiency of museums was studied both for a single year (Kim & Chung 2019; Guccio et al. 2020a) and several years (del Barrio-Tellado & Herrero-Prieto 2022; Del Barrio-Tellado et al. 2023) – depending on the purpose of the analysis and the availability of data. The number of museums surveyed also varied – from a dozen (Šebová 2018), through several dozen (Haruna et al. 2012), to several hundred (Guccio et al. 2020a) – this also depended on the availability of data.

Researchers accepted different categories of data for analysis, which resulted from their availability and the research goal adopted. Although no universal set of variables has been observed in the research on the efficiency of museums, it has been noted that some of them occur more often than others (see Appendix A2). On the one hand, the authors often assumed (Brzezicki 2024) the following as inputs in the DEA model: the number of employees, the area of the museum, the number of museum objects (collections) or the costs of operating the museum. On the other hand, the following were usually taken as outputs: the number of visitors, the museum’s revenues (e.g. from tickets) or the number of exhibitions. In the few studies, the authors have assumed other variables, depending on the research perspective of a given area of the museum’s activity (Basso & Funari 2020).

The authors, who, in addition to measuring the efficiency of museums, also estimated the impact of environmental variables on efficiency, used either variables characterizing the region in which the museum operated (Del Barrio-Tellado et al. 2023) or variables related to the museums themselves (Guccio et al. 2020a).

First of all, the object being the subject of the study should be defined in general. Pursuant to the Act of 21 November 1996 on Museums

a museum is a non-profit-oriented organizational unit, the purpose of which is to collect and permanently protect the natural and cultural heritage of humanity of a tangible and intangible nature, to inform about the values and content of the collections, to disseminate the basic values of Polish and world history, science and culture, to shape cognitive and aesthetic sensitivity and to enable use of the collected collections.

The said Act shows that museums carry out their mission by achieving the following objectives:

- 1)

collecting monuments in the statutorily defined scope;

- 2)

cataloguing and scientific processing of the grouped collections;

- 3)

storing the collected artefacts in conditions, ensuring their proper state of preservation and safety, and storing them in a manner accessible for scientific purposes;

- 4)

securing and conserving collections and, as far as possible, securing immovable archaeological monuments and other immovable objects of material culture and nature;

- 5)

organizing permanent and temporary exhibitions;

- 6)

organizing research and scientific expeditions, including archaeological ones;

- 7)

conducting educational activities;

- 8)

supporting and conducting artistic and cultural dissemination activities;

- 9)

making collections available for educational and scientific purposes;

- 10)

ensuring appropriate conditions for visiting and using the collections and the collected information;

- 11)

conducting publishing activities.

In the second stage of the study, in order to determine the number of museums and create their database (including contact details), lists of museums operating in Poland were analysed. The MCNH, in accordance with the Act of 21 November 1996 on museums, maintains two public lists: (1) the National Register of Museums and (2) the List of Museums. From the perspective of national heritage, the first one is more important, because, as indicated by the aforementioned Act, it only includes museums that have a confirmed high substantive level of their activities, and also have collections of great importance. In addition, the Minister makes the entry in the Register dependent in particular, on the importance of the museum’s collections, team of qualified employees, premises and a permanent source of financing – ensuring the fulfilment of the museum’s statutory objectives. On the other hand, the list of museums includes all museum units that have a statute or regulations of activity agreed with the MCNH.

In the next stage of the analysis, the sources of potential data in Poland were identified, which could prove useful in the conducted research. This is an aspect closely related to the second research question posed in the introduction to the work. The following sources of data on museums in Poland have been identified, in the form of reports and surveys:

SP:

- a)

Report on the activities of the museum and the para-museum institution (K-02),

- b)

Annual report on the finances of cultural institutions (F-02/dk).

- a)

NIM:

- a)

Organization and management – survey on museum statistics (KK-3 OZ),

- b)

Infrastructure and security – survey on museum statistics (KK-3 IB),

- c)

Collection management – survey on museum statistics (KK-3 ZZ),

- d)

Dissemination activity – survey on museum statistics (KK-3 DU).

- a)

While the reports of the SP are carried out annually, on the basis of the same report forms, the NIM collects data in cycles of several years. This means that in the following years the NIM collects different data (based on thematic surveys), and only after a few years does it survey museums on the same subject again. NIM collects data from museums that have a statute or regulations of activity agreed with the MCNH, i.e. on the basis of the List of Museums. It is worth noting that the data collected by the NIM as part of museum statistics have been included since 2022 in the SP official statistics research program. This means that the SP receives data from the NIM. At the same time, the SP, on the basis of its own reports and data provided by the NIM, publishes its own reports.

Subsequently, individual museums included in the MCNH lists were directly asked to provide public information in relation to the above-mentioned complete reports (K-02) and surveys (KK-3 OZ) for the purposes of this scientific study. Therefore, in order not to reduce the number of analysed objects too much, it was decided to rely on these two types of forms in the selection of categories for the study. It was also decided that the analysis will be carried out on the basis of the data obtained from 2023, which, on the one hand, were the most recent and numerous, and on the other hand, are not burdened with distortions caused by the situation that took place during the Covid-19 pandemic, including restrictions on access to cultural services (Lipski 2021). The use of source data, unprocessed (K-02 and KK-3 OZ) compiled on the basis of the same methodology (ST and NIM) allows for consistency and objective comparability between individual museums. Data obtained from different entities without taking the above assumptions into account may be incomparable, as each entity may record or understand the definition of a given issue in a different way. The use of data contained in standardized reports and surveys avoids these problems and allows for repeated research in the future, which is crucial in the field of science. Requests for access to public information were sent to 302 museums. The data in the form of electronic PDF files (editable files or scans) was finally sent by 284 museums. It turned out that not all museums filled in the NIM form (KK-3 OZ) requesting information. The data contained in the reports (K-02) and surveys (KK-3 OZ) sent by the museums were manually transcribed into a spreadsheet. In the case of incomplete data or doubts about some of the information, individual museums were contacted electronically to supplement the data or obtain clarification. The only document sent by all 284 museums was the obligatory ‘Report on the activities of the museum and para-museum institution’ (K-02) sent annually to the SP. The second largest form was the ‘Organization and Management’ questionnaire (KK-3 OZ). Next, certain entities were excluded from the manually created database based on the reports and surveys obtained from museums. Museums with incomplete data that could not be supplemented or clarified, as well as entities that significantly deviated from the rest of the research sample, were excluded from the study. Ultimately, 174 museums were included in the study. The study of museums based on source data contained in standardized reports and surveys aims, first of all, to check whether the available data sources allow for the examination of these entities. Secondly, it aims to assess whether it is possible to evaluate the activities of museums in terms of specific tasks defined in the Act. Thirdly, and most importantly, it aims to examine the efficiency of these entities, filling a research gap.

As mentioned in the introduction to the paper, its main goal is to measure the efficiency of museums using the DEA methodology, which treats the analysed objects as production units (DMUs, Decision Making Units) that obtain one or more products (outputs) from specific inputs. In the literature on the subject, several types of efficiency are distinguished (Brzezicki 2025). However, it was decided to analyse museums in terms of technical efficiency, which is related to the technological production capabilities of a given DMU, and in which the prices and costs of production factors are not considered (Brzezicki 2025).

The choice of this type of efficiency was dictated by the fact that the managing bodies – public entities – secure the financing of museums in the form of subsidies for basic activities, which are used to finance the salaries of employees and fees for the maintenance of the museum. Therefore, museums are not profit-oriented, and the financial resources in a short period (annual) are permanent, not related to the number of exhibitions or visitors.

After comparing the objectives of the statutory activities of museums in Poland with the currently available sources of data on these objects (see Appendix A1), it was decided to analyse the efficiency in terms of objectives 5) and 7)-10). And even so, due to the aforementioned data gaps, the number of analysed DMUs had to be limited to 174. In this respect, two main areas of research have been distinguished:

analysis of the efficiency of the implementation of activities encouraging interest in the museum’s offer;

analysis of the efficiency of these activities in terms of the number of visitors and the number of participants in various types of events organized by the museum.

These areas are closely related to each other. Therefore, they were treated as elements (so-called divisions) of the appropriate DEA network model, which will be discussed later.

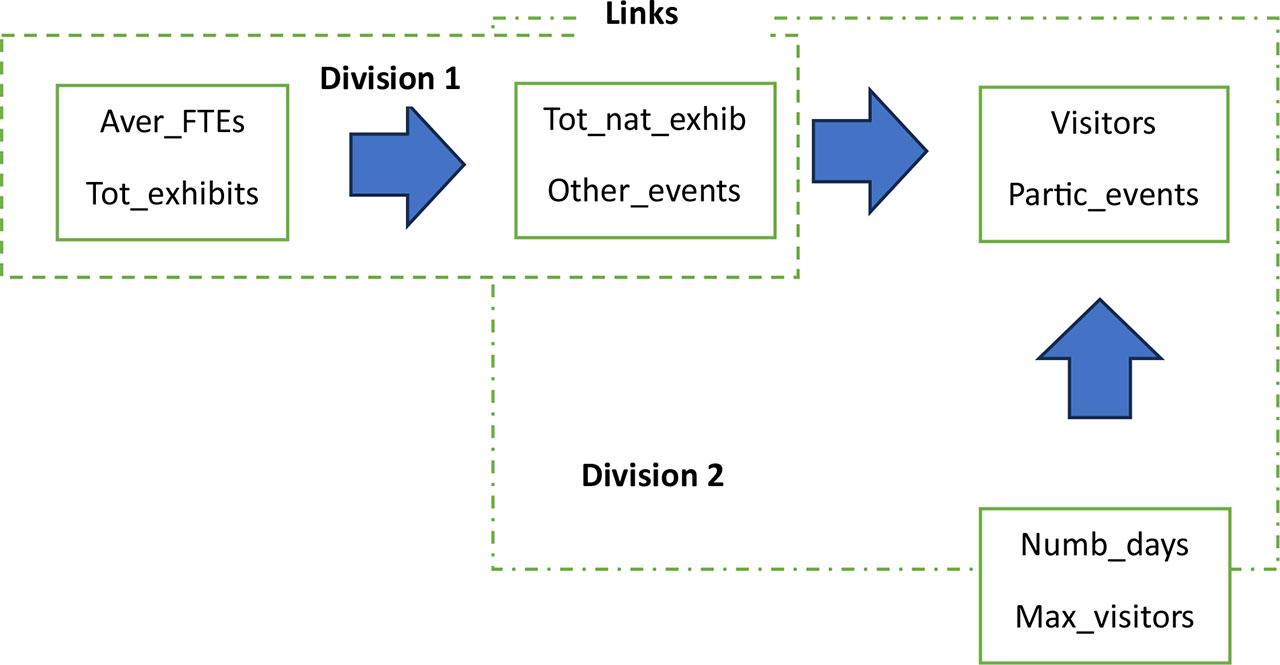

Inputs in the first division, i.e. in the first area of research, were:

average number of employees calculated in FTEs (Aver_FTEs, KK-3 OZ), representing the labour factor;

the total number of exhibits in inventory items (Tot_exhibits, K-02), as an approximation factor of the specific capital of museums.

It was assumed that museum employees, using the exhibits, create the following ‘products’ within the first, analysed area of activity (the first division):

total number of national exhibitions (Tot_nat_exhib, K-02);

number of events carried out as part of other cultural, scientific and educational activities (Other_events, K-02).

In order to make the museum’s offer more attractive, various types of accompanying events are organized and supporting the understanding of the complexity of the nature of the exhibition. The events have a strictly defined character, related to the museum’s activities. On the one hand, they are aimed at attracting additional participants interested in a given topic, who are potential visitors to the museum. On the other hand, it is necessary to present the museum values gathered in the museum in a wider range in a different way than usual, e.g. through curatorial tours, meetings, lectures referring to the main subject of the exhibitions. In addition, it is worth noting that as part of various events, activities are carried out that museums are obliged to do, related to educational, scientific, artistic and cultural dissemination activities, which are addressed to appropriate groups of recipients (Kwiatkowski & Nessel-Łukasik 2017).

It was assumed that the activities of the employees, defined by the two ‘products’ above, attract visitors and participants of the aforementioned events organized by the museums. Therefore, they are also inputs of the second division, modelling the second of the analysed areas of activity. Therefore, in the DEA network model, which will be presented later, these activities play the role of the so-called as-output links or good links. Links are intermediate variables connecting both divisions, i.e. both analysed areas of museum activity. As is apparent from the description of the second area of activity analysed (Second Division), its outputs are the number of visitors (Visitors, K-02) and the number of participants in events (Partic_events, K-02).

Of course, museum employees also carry out other activities, e.g. issuing publications, on-line activities, digitization of collections and their conservation, related to other goals of the museums’ activities. Some of these omitted activities may have an impact on the two areas of activity analysed (cf. Appendix A1). Unfortunately, as mentioned earlier, there are too many data gaps for these categories to consider. It should also be noted that a large number of museums did not operate in this area in 2023 (e.g. the exhibits were not conserved or digitized).

In addition, it was assumed that the number of visitors and participants of events is influenced by:

the maximum number of visitors who can stay in the museum at one time (Max_visitors, KK-3 OZ), treated as an approximation of the area of objects, not available directly in the collected data for most museums;

the number of days in a year when the museum was open (Numb_days, KK-3 OZ), determining the time availability for visitors.

These are the inputs of the second division, which this time are not related to the first division. These factors represent the accessibility of museums and complement the ‘network’ model of museum functioning, which is graphically illustrated in Figure 1.

The model of the study of museums adopted in the analysis

Source: own elaboration

In this work, the SBM network model proposed by Tone and Tsutsui (2009) was used to measure the efficiency of museums. The choice of the network model based on the non-radial SBM model was dictated by the fact that, unlike the radial models (CCR and BCC), it does not assume that only proportional changes in inputs or products lead to full efficiency.

The selected SBM network model has been adapted to two divisions of equal importance, by using the same weight for each of them. Division-to-division connections, on the other hand, are described by variables called links. In this analysis, links are treated as outputs links, although they also play the role of inputs in division two.

Due to the different size and degree of organizational development of museums, variable returns to scale (VRS) were adopted in the SBM network model. In addition, the output-oriented model was chosen, because the efficiency of museums is understood here as the inability to obtain a larger number of outputs from the currently owned number of inputs. With this assumption, the model defines the efficiency measures of museums within individual segments (divisions). In turn, the total measure of the efficiency of these DMUs is calculated as the harmonic mean of the divisional efficiency measures. It provides the ability to interpret the measure of total efficiency as the inverse of the average of the relative potential increases in all outputs that can be achieved from the current amount of inputs.

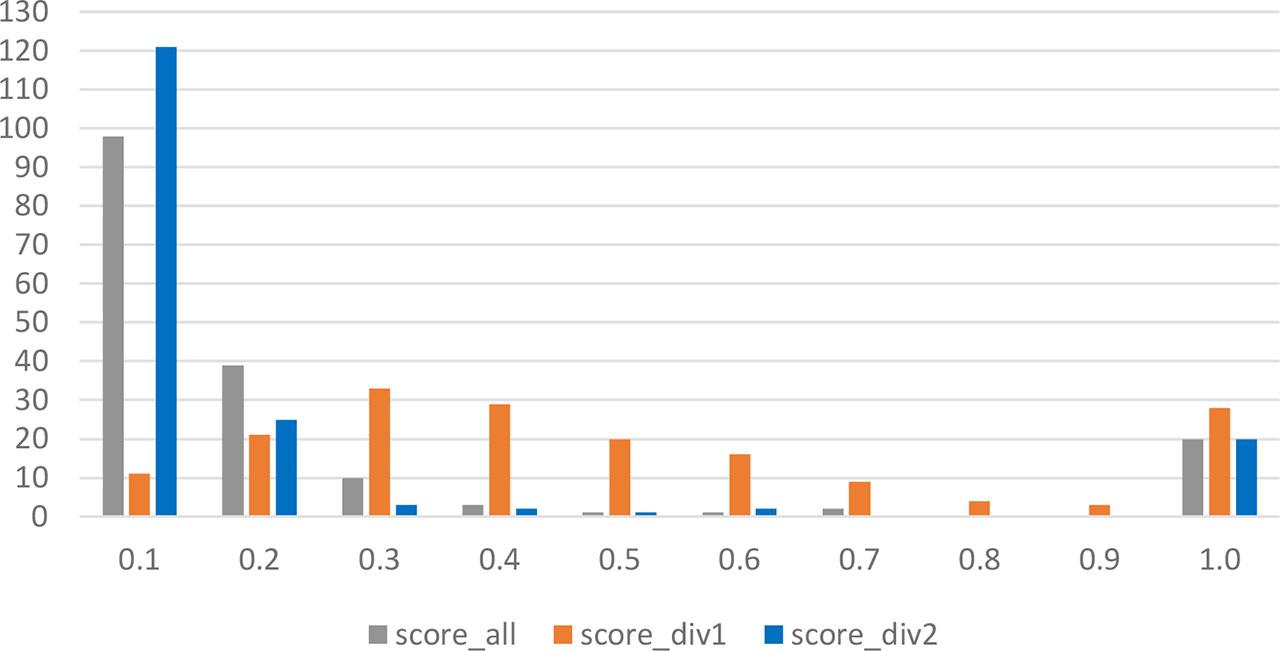

In order to answer the third research question, the SBM network model was used to examine the efficiency of the implementation of activities encouraging interest in the museum’s offer (division 1) and efficiency of these activities in the field of attracting visitors and event participants (division 2). Histograms of the relevant measures are shown in Figure 2.

Histograms of efficiency indicators

Source: own elaboration

The analysis shows that the vast majority of the surveyed museums (121; 69.54%) are characterized by a negligible ability to attract specific ‘customers’ of museums, such as visitors and participants of events (score_div2 ∈ [0; 0.1]), compared to museums considered efficient in this respect (relative nature of the measure).

According to the authors, low efficiency may result not only from poor operational efficiency, but also from the existence of certain factors that are neither inputs nor products (conventionally called environmental), which may have a significant impact on it.

It is also of great importance that the number of visitors, and especially the number of participants in events, is determined by some museums only as an estimate, with a large approximation. This may be partly due to the lack of appropriate devices or measurement systems with which they should be provided by the authorities running museums. Another problem faced by museums, indicated by employees when obtaining data for the purposes of the article, is the issue of how to count museum visitors in a situation where they offer several different exhibitions for which separate tickets can be purchased. Unfortunately, the current version of the relevant reports does not allow for reporting these differences.

In addition, the low efficiency of most museums in this area may also result from the already mentioned fact that museum employees carry out other activities, such as issuing publications, on-line activity, digitization of collections and their conservation, which are equally important for the operation of museums, because they are specified in the Act, and for which sufficient complete data has not been obtained.

On the other hand, much better efficiency of museums in the implementation of activities that could potentially attract visitors and participants of events (division 1) was observed. For example, only 11 facilities (6.32%) are extremely inefficient (score_div1 ∈ [0; 0.1]), but there are more museums that are fully efficient in this area (28), compared to the aspect of attracting visitors and event participants.

This means that most museums are relatively efficient in carrying out activities that ‘attract customers’. However, this does not have the intended effect. This may be due to the fact that the analysis took into account the quantitative nature of the exhibits presented, and not the quality of museum services and public interest in the subject matter of exhibitions presented in museums. This means that a large number of exhibits doesn’t always translate into a large number of visitors. Another explanation may be the presence of the aforementioned external factors, which will be discussed later in the analysis.

Figure 2 also presents the harmonic mean of efficiency measures from both analysed areas of museum activity. It is treated, based on the construction of the appropriate model, as a measure of the total efficiency of the objects. The average value of the overall efficiency was only 0.205. On the other hand, the average efficiency of Division 1 and Division 2 was 0.458 and 0.175, respectively. Therefore, a strong impact of the low efficiency of museums in the second of the analysed areas (division 2) on the overall efficiency is visible.

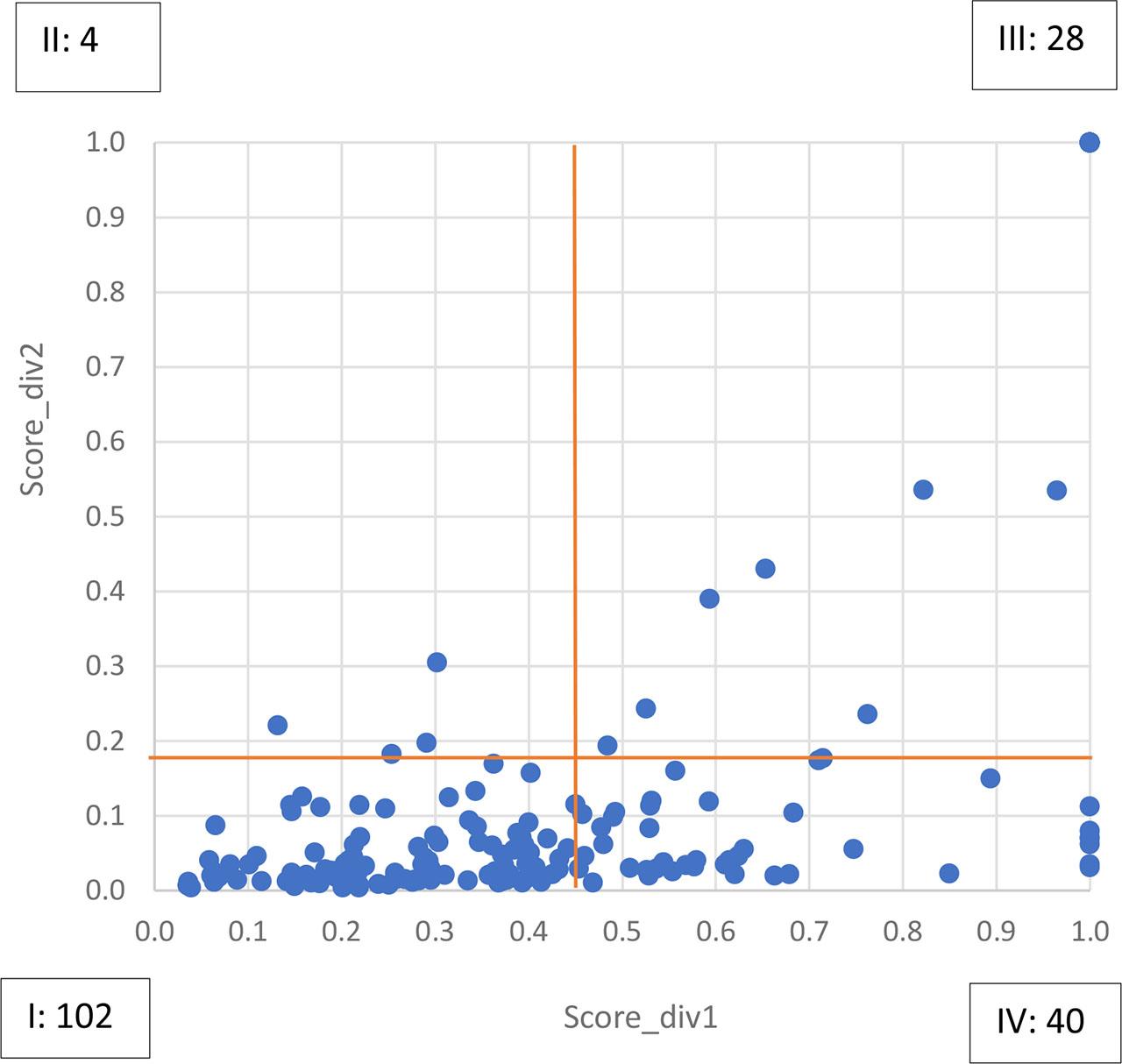

In the next step of the analysis, it was decided to compare the results for both divisions for individual museums against the value of the average efficiency for each division (Figure 3). On the one hand, this will illustrate the efficiency of individual museums in both aspects of their activity. On the other hand, and more important, this will classify the studied individuals into four groups, which form four quadrants, defined by the axes determined by the aforementioned means. Museums in each group should adopt different strategies to improve their performance results.

Comparison of the efficiency of museums in individual divisions in relation to the average measure of efficiency for each

Source: own elaboration

The largest group (102 objects), located in the first quadrant marked in Figure 3, are museums, which are characterized by lower efficiency than the average in both the first (<0.458) and second (<0.175) divisions. This means that these museums are not sufficiently exploiting their potential to create more diverse exhibitions and events (div.1). As a result, other museums, with a similar number of staff (counted in full-time positions) and collections, can carry out many more activities of this type. In this group of museums, the number of visitors and participants in events is also small in relation to the number of exhibitions and events organised and their accessibility, measured by the maximum number of visitors that can be in the museum at one time, and the number of days per year when the museum was open (div.2). A possible solution is to audit the organization and management of the museum’s activities and take corrective steps. These museums should also revise their promotion policies to better attract visitors and encourage them to participate in the events organised by the entity.

The second largest group are museums (40), which achieved higher than average efficiency in the first division and lower than the average in the second division. The results indicate that the way the museum operates and manages is at an above-average level for these units. However, these museums need to focus more on promotional activities to attract visitors and event participants. A possible solution here is, for example, to conduct research on social expectations in the field of providing museum services in order to identify which aspects of activity are well evaluated and which are unsatisfactory for potential visitors. It is also worth considering comparing the promotional activities of a museum considered to be more efficient in this area and implementing similar solutions in an inefficient museum.

The third largest group are museums in the third quarter, which achieved higher than average efficiency within both divisions (28 objects). Several interesting facts have been observed. Firstly, it should be emphasized that as many as 20 museums achieved 100% efficiency in two divisions. The activities of these museums have therefore proved to be fully efficient in both aspects under consideration and interrelated. Second, it was noted that the level of inefficiency of the four museums in this group was similar in both divisions. Eight inefficient museums from this group have a good chance of achieving full efficiency with a significantly smaller increase in their activity than in the case of units qualified to the first quarter.

Only four museums were qualified for the last group. However, this group is particularly interesting from the perspective of assessing the activities of individuals through the social prism. Although these museums did not organize as many exhibitions and events as other units with a comparable number of staff and exhibits, this did not prevent them from attracting a larger number of visitors and participants of events. This means that the topics presented in the museum and the nature of the events were interesting for the society. One museum achieved the same level of efficiency (0.3) in two divisions. This means that the operations were conducted in a sustainable manner, although not very efficient compared to the entities considered fully efficient.

Table 1 presents the efficient objects in both divisions, along with the identification of the managing body.

A list of museums fully efficient in both divisions

| Name of the Museum | Div1 | Div2 | Managing Body |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central Museum of Prisoners-of-War | 1.00 | 1.00 | Voivodeship |

| Museum – House of the Pilecki Family in Ostrów Mazowiecki | 1.00 | 1.00 | MCNH |

| Museum - Manors of the Karwacjan and Gładysz Families in Gorlice | 1.00 | 1.00 | Voivodeship |

| Museum – Górków Castle in Szamotuły | 1.00 | 1.00 | District |

| Museum of the Battle of Grunwald in Stębark | 1.00 | 1.00 | Voivodeship |

| Częstochowa Museum | 1.00 | 1.00 | District |

| Museum of the History of the Polish People’s Movement in Warsaw | 1.00 | 1.00 | Voivodeship |

| Historical Museum in Lubin | 1.00 | 1.00 | Commune |

| Royal Łazienki Museum in Warsaw | 1.00 | 1.00 | MCNH |

| Museum of the City of Jaworzno | 1.00 | 1.00 | District |

| Dzierżoniów City Museum | 1.00 | 1.00 | Commune |

| The National Museum in Warsaw | 1.00 | 1.00 | MCNH |

| District Museum in Sieradz | 1.00 | 1.00 | District |

| Museum of King Jan III’s Palace at Wilanów | 1.00 | 1.00 | MCNH |

| Regional Museum in Kościan | 1.00 | 1.00 | Commune |

| Stanisław Staszic Museum in Piła | 1.00 | 1.00 | Commune |

| Stutthof Museum in Sztutowo | 1.00 | 1.00 | MCNH |

| Museum in Praszka | 1.00 | 1.00 | Commune |

| Armoury Museum at the Liw Castle | 1.00 | 1.00 | Voivodeship |

| Museum of the Sącz Land in Nowy Sącz | 1.00 | 1.00 | Voivodeship |

Source: own elaboration

Table 1 shows that the number of efficient museums run by different entities was similar (5 – communes, 4 – districts, 6 – voivodeships, 5 – MCNH). Therefore, both large museums of national importance, run by the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage (e.g. the Royal Łazienki Museum in Warsaw, the Museum of King Jan III’s Palace at Wilanów), as well as medium-sized and smaller museums run by voivodeships, counties and municipalities, were fully efficient.

Averages of the measures of total efficiency in groups of museums distinguished by the managing body were also calculated, and it turned out that they are also similar and amount to 0.189 for municipal museums, 0.200 for district museums, 0.202 for provincial museums and also 0.202 for museums run by the MCNH.

Contrary to appearances, this does not mean, however, that there is no significant relationship between the level of efficiency of museums and the managing body, treated as an environmental factor (see the further part of this chapter).

The analysis is relative, i.e. museums are compared with each other in terms of the outputs obtained from the current amount of inputs. Therefore, some museums create models of conduct in the analysed scope for other objects, called benchmarks. Table 2 shows which museums were the most often components of such benchmarks in at least one of the two analysed areas of museum activity.

Museums that are most often components of benchmarks

| Name of the Museum | Division 1 | Division 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Museum - Manors of the Karwacjan and Gładysz Families in Gorlice | 126 | 0 |

| Museum of the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw | 0 | 44 |

| Henryk Sienkiewicz Museum in Wola Okrzejska | 11 | 37 |

| Royal Łazienki Museum in Warsaw | 26 | 152 |

| Museum of King Jan III’s Palace at Wilanów | 69 | 9 |

| Museum of Papermaking in Duszniki Zdrój | 95 | 0 |

| Armoury Museum at the Liw Castle | 0 | 41 |

| Museum of the Krajeńska Land in Nakło nad Notecią | 53 | 0 |

Source: own elaboration

The list includes museums of various sizes, run by different bodies, functioning both in smaller towns and large cities. This raises the question of what factors made the selected museums benchmark units.

For example, the Museum in King Jan III’s Palace at Wilanów is run by the MCNH due to the collections gathered inside. In addition, it is located close to the capital of the country and has facilities for people with disabilities in the form of a mobile application (Manczak et al. 2021). It is worth noting that it is among the 10 most visited museums in Poland (Kruczek, 2024).

On the other hand, the Museum of the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, unlike the other museums listed in Table 2, is run by a public university and presents a separate subject matter. This may indicate that the subject matter of the exhibitions, or in other words – the nature of the museum, may be an important factor influencing the inclusion of this unit in the benchmarking list. Another explanation may be the organizational form or model of work, because the museum is run by a university which, by virtue of the law, has significant autonomy in its activities and can manage its subordinate unit in a different way. The issue of museum autonomy was highlighted by Plaček et al. (2020), who analysed the efficiency of Czech museums.

In the case of the Museum of Papermaking in Duszniki Zdrój, a likely factor influencing its being a component of benchmarks, may be its openness, including workshop activities for visitors. Another factor influencing the efficiency may be multi-themed, as in the Museum - Manors of the Karwacjans and Gładysz in Gorlice, where you can visit an art gallery, an open-air museum of the village, a homestead and an Orthodox church.

In this way, we come to the issue of the impact on the level of efficiency of factors that are not inputs or products in the presented model, conventionally called environmental factors, which is the content of the fourth research question. In the literature, various types of regression models are used to analyse the impact of these types of factors (Guccio et al. 2020a, Del Barrio-Tellado et al. 2023), especially truncated or censored regression. In this paper, for example, the tobit regression model, which is a type of censored regression, is used.

Guided mainly by the availability of data and the statutory objectives of the activity considered in this paper (cf. Appendix A1), the following external factors were considered:

the number of inhabitants of the town where the main seat of the museum is located (https://www.polskawliczbach.pl/); it should be noted that it happened that branches of a given museum were located in different towns; this variable has often been used in research on cultural institutions, including museums, e.g. (Plaček et al. 2020);

adaptation of the object to the needs of the disabled (K-02) – zero-one variable; It is worth mentioning that the efficiency of museums is influenced by their accessibility, for example, for people with disabilities (Kruczek et al. 2024). That’s why we assumed two variables related to it;

adaptation of the exhibition to the needs of people with disabilities (K-02) – zero-one variable;

possibility to buy tickets online (K-02) – zero-one variable;

type of museum (K-02), represented by a group of zero-one variables corresponding to museums: martyrological, art, historical, ethnographic-anthropological, archaeological, technical and scientific, and interdisciplinary; due to the collinearity of this group of variables, all interpretations in this respect will be referred to the so-called reference category, which is assumed to be the interdisciplinary nature of the museum;

the managing body (K-02), represented by a group of zero-one variables corresponding to the museum run by municipalities, districts, voivodeships and the MCNH; due to the collinearity of this group of variables, all interpretations in this regard will be referred to the so-called reference category, which is considered to be museums run by the MCNH.

Due to the fact that one of the museums was run by a university, i.e. a body not included in the above list, it was eliminated from the analysis of the impact on the efficiency of external factors. This object was very inefficient in both divisions, so its removal had no effect on the results obtained.

These factors acted as explanatory variables in the aforementioned tobit regression model. On the other hand, the role of the explained variable was played by the inverse of the measure of total efficiency minus one. The domain of this variable is then, classic for tobit regression, the interval [0, ∞).

With the help of the Gretl program, the structural parameters of the model were estimated, and then backward stepwise regression was carried out in order to isolate environmental factors significantly affecting efficiency.

It turned out that a factor significantly positively related to the overall efficiency of the museum’s operation in both areas is the possibility of purchasing tickets via the Internet. This means that the possibility of purchasing tickets online has a positive effect on the efficiency.

It should be emphasized that museums should implement more ICT (Information and Communication Technologies) solutions, which after the pandemic have become widely used in various aspects of human activity. Only 33% of the surveyed museums have an electronic ticket purchase system via the Internet. It was noted that 88% of the surveyed museums collect data on the number of website views, and 86% on the number of unique users. In several cases, however, it was observed that these were estimated data and not real ones. It should be emphasized that in many industries, this type of data is crucial in analysing the efficiency of promotional activities and evaluating the organization’s activities. Only 41% of the surveyed museums carried out their activities online. In addition, the analysis of the collected data indicated that 81% of the surveyed museums have digitized their collections.

However, it is worth noting that the examples are for basic ICT functions, while recent literature points to advanced ICT, such as Virtual or Augmented reality and other digital solutions in museums (Li et al. 2024). Unfortunately, in the available reports and reports of museums, there is no information about advanced ICT mentioned in the recent literature. The scope of ICT information in museums in Poland is limited only to virtual tours, store activities or social media activity. Given that not every museum has implemented even simple ICT solutions, it should be assumed that far fewer units have more advanced ICT solutions.

Although the variables related to the adaptation of the building and the exposure to the needs of people with disabilities turned out to be insignificant, it is worth noting that most of the analysed objects are adapted to the needs of these people. As many as 80% of the surveyed museums are adapted to people with disabilities at least in one aspect (entrance to the building or inside the building) or at least in relation to one branch. On the other hand, 54% of museums have (at least in one branch) exhibitions adapted to the needs of people with disabilities. This means that access to cultural and heritage goods in museums is properly organised in this respect. However, there is still room for further improvement in this area.

An important factor that has a negative impact on the efficiency of the museum’s operation is its ethnographic and anthropological character. Museums of this type operate less efficiently compared to interdisciplinary museums (see footnote 6). The results may suggest that such museums are not preferred by visitors, especially in relation to museums that offer a more diverse theme of exhibitions.

It was also found that museums run by the MCNH are characterized by a significantly higher level of efficiency than museums run by local government bodies. A study by Del Barrio-Tellado et al. (2023) also found a significant relationship between the efficiency of Spanish museums and the lead authority, but only for locally owned museums (municipal and provincial administrations) and church museums. For national and regional museums, no significant correlations were found in this work.

In this paper, first of all, a review of Polish and foreign literature was carried out, which showed that quantitative research on the efficiency of museums is being conducted abroad, while in Poland no such research has been conducted yet. Foreign studies of museums using the DEA method are quite diverse in many respects. The authors used both different DEA models and diverse data that corresponded to the objectives of the study. Polish studies of museums, on the other hand, focused on aspects of museum functioning and the impact of these institutions on tourism and the economy rather than on efficiency analysis. A review of Polish publications on museums and statistical data sources revealed summary reports carried out by SP and NIM characterising the museum sector. However, they can only be used for illustrative purposes, as the data is aggregated and therefore cannot be fully utilised for empirical research using quantitative methods. In view of the above, SP reports and NIM surveys were identified that could serve as a basis for broad and detailed analyses of individual museums.

Next, the source of statistical data for this study was selected, and the efficiency of museums’ activities was measured and evaluated based on the adopted research objective. The results of the study indicate that museums are characterised by low efficiency in terms of two aspects of their activities. However, in terms of increasing the number of visitors and event participants, they are less efficient than in terms of the efficiency of the implementation of activities encouraging interest in the museum’s offer.

Thirdly, regarding the impact of external factors on efficiency, it was noted that the overall efficiency of both areas was significantly positively influenced by the possibility of purchasing tickets online. In addition, the study showed that ethnographic and anthropological museums are significantly less efficient than interdisciplinary museums.

The poor efficiency of museums may be influenced by the frequency of research and control of their own activities by the museum. Ćwikła et al. (2022) points out that research conducted in Poland shows that as many as 81% of public cultural institutions see the need to conduct research on their functioning and management. However, only 53% confirmed that institutions had conducted such surveys in the last five years. It should be emphasized that the smaller the cultural institution, determined on the basis of the number of employees, the lower the need to conduct research. The lack of systematic research of cultural institutions leads to a lack of information about the efficiency of their activities, and consequently to the lack of appropriate corrective actions.

This is probably due to the current system of subsidies by public supervisory bodies, which provide funds for the functioning of cultural institutions, including museums (employee remuneration and utility fees) regardless of the number of visitors and the number of accompanying events. Data from the SP and Statistical Office in Kraków (2023) shows that more than 75% of the budget of cultural institutions comes from the basic subsidy. On the other hand, the funds from the purchased tickets only supplement the budget of museums (over 10%).

It is also worth noting that even when museums evaluate their own activities, they do not have the opportunity to compare the results with other museums, which makes them unable to draw reliable conclusions. The data collected by NIM are published in the form of aggregated, summary results for all museums in Poland and therefore have a low value for comparing the results between individual museums. Therefore, there is no appropriate system for evaluating and presenting the activities of individual museums in Poland. A possible solution is to adapt solutions used in the higher education sector, where each university can compare its results with other universities after evaluation.

This paper presents a method of assessing the efficiency of museums in two related areas that could solve these problems. Of course, this assessment should also be extended to the areas of activity of museums not analysed in this work, but related to their statutory objectives of activity 1)-4), 6) and 11) presented at the beginning of the methodological part. According to the authors, the only thing that stands in the way of achieving this and creating a coherent system for assessing the efficiency of museums in all their areas of activity are deficiencies and errors in the obtained data (cf. Appendix A1).

It is worth noting here that the literature on the subject (Guccio et al. 2020a) also emphasizes the importance of using modern ICT devices and systems, which, nowadays, significantly support the implementation of most of the statutory objectives of museums. Unfortunately, the annual report K-02, which is the basis for the analyses in this paper, does not consider such data. On the other hand, NIM reports, although very extensive, are carried out every four years and optionally, so there is a lack of current and complete data on the implementation of modern solutions in the museum sector. The authors plan to investigate the efficiency of museums in the implementation and efficiency of ICT systems, but, due to the aforementioned data gaps, this will be done on a significantly smaller group of objects.

With regard to the low level of efficiency of ‘acquiring’ visitors and event participants, achieved in this work, museums should also make greater use of the observations and recommendations of the NIM, which implemented the ‘Museum Audience’ project in Poland in 2017–2021 (Kwiatkowski et al. 2022). The first edition of the NIM survey from 2017 (Kwiatkowski & Nessel-Łukasik 2017) shows that museums did not sufficiently study the public. The frequency of surveying the public sporadically or less often than once a year was declared by as many as 43% of museums. On the other hand, once a year – 19%, and two or three times a year only 17% of museums.

The vast majority of museums conducted the aforementioned research only in the form of a standard, paper survey. The authors of the NIM study indicate that these studies should consider various research methods, including quantitative ones. Regardless of the frequency of audience research, the most important thing seems to be to draw appropriate conclusions from these analyses and implement changes in the functioning of museums in various areas of activity.

It is worth noting that the aforementioned 2017 study drew attention to many other problems of museums – from the appropriate presentation of museum resources or the arrangement of museum space to the dimension of organizational culture, including the openness of the museum and the expectations of various groups of recipients.

In addition, according to the authors of the study (Kwiatkowski & Nessel-Łukasik 2017), the bodies running museums (mainly various local government units) should be more actively involved in activities improving the efficiency of units. The local government should involve museums in the implemented promotion policy of the region and tourism in a more thoughtful way. This is also confirmed by other results of the NIM research, which indicate that good cooperation between the museum and the local government and other cultural institutions contributes to the improvement of the functioning of museums.

This paper also indirectly demonstrates the need for greater involvement of local government bodies in the activities of their subordinate museums. It turned out that the efficiency of the ‘self-government’ museums in the two related areas analysed in the paper is significantly lower than the efficiency of the museums run by the MCNH.

The radial CCR model is named the first letters of the authors’ last names, Charnes, Cooper and Rhodes, (1978). Constant returns to scale are assumed in the CCR model.

The radial BCC model is named the first letters of the authors’ last names, Banker, Charnes and Cooper (1984). In the BCC model, the assumed variable returns to scale.

The non-radial slacks-based measure (SBM) model was presented by Tone (2001). There are many developments and modifications of the SBM model in the literature. A comprehensive review of various SBM models can be found in the publication Emrouznejad et al. (2025).