The determination of audit fees is a crucial area of study in both accounting and auditing, influenced by numerous factors that impact audit service costs. This matter is of utmost importance, especially in developing economies like Kosovo, where the development of the audit market is still ongoing. Kosovo presents a compelling and underexplored empirical context, or a “natural laboratory”, for investigating audit fee determinants. This characterisation is supported by several distinctive features of Kosovo's institutional and economic environment. As a post-conflict nation, Kosovo has undertaken comprehensive efforts to build its regulatory and professional infrastructure from the ground up. The mandatory and accelerated adoption of International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) and International Standards on Auditing (ISA) has imposed complex compliance requirements within a market characterised by limited capacity and resources. Moreover, the economy is predominantly composed of micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs), which shape a markedly different audit landscape compared to that of advanced economies. Perhaps most notably, the underdevelopment of enforcement mechanisms introduces atypical auditor–client dynamics that may significantly influence audit pricing behaviour. These contextual specificities suggest that the conventional determinants of audit fees established in more mature settings may not hold in Kosovo. Hence, our study contributes to the literature by examining how audit fees are determined in a transitional environment marked by institutional voids and evolving governance structures.

Client size, client complexity, client risk, and audit firm reputation are the most common factors in determining fees (Simunic, 1980; Hay et al., 2006). These determinants are equally relevant in Kosovo, yet the unique dynamics and challenges of the local market warrant further exploration. A clear understanding of the determinants is crucial for ensuring fairness and transparency in the audit process, benefiting both auditors and clients, as well as other stakeholders.

Prior to the introduction of Law No. 06/L-032 on Accounting, Financial Reporting, and Auditing on January 1, 2019, a vacuum existed in Kosovo's audit market. This law governs how companies must carry out accounting and financial reporting, outlines the roles and responsibilities of the Kosovo Council for Financial Reporting (KCFR), and sets auditing standards and qualifications for accountants, auditors and audit firms. Its alignment with EU directives allows Kosovo's auditing practices to conform to international standards on auditing – ISA (Hoti & Sopa, 2022). The enactment of Law No. 06/L-032 introduced a comprehensive regulatory framework aimed at formalising and standardising the audit profession in Kosovo. Key provisions of the law include the mandatory licensing of both domestic and international audit firms by the Kosovo Council for Financial Reporting (KCFR), thereby restricting audit practice to qualified entities that meet established ethical and professional standards. In addition, the law mandates rigorous certification requirements for auditors, including extensive training and the successful completion of standardised examinations, ensuring a baseline of professional competence across the market. Perhaps most critically, the law empowers the KCFR with oversight and enforcement authority, enabling systematic monitoring of compliance and creating deterrents against malpractice. Collectively, these reforms have introduced a degree of regulatory stability and standardisation previously absent in Kosovo's audit market. These conditions are instrumental for evaluating how audit fees are determined in transitional institutional settings.

While the enactment of this law has indeed affected the audit market in Kosovo, it has also brought about a measure of standardisation that had not existed before. Aligning with international standards, audit practices in Kosovo are gaining greater reliance among foreign investors, as they seek more assurance regarding the accurate and reliable preparation of financial statements.

Kosovo offers a rare post-conflict, EU-accession audit setting combining (i) institution-building from a “clean slate,” (ii) mandatory IFRS and ISA adoption, yet (iii) a micro-economy dominated by MSMEs and informal practices. This case constitutes an extreme case (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007) where canonical audit pricing theory may not hold. Accordingly, our research makes three original contributions: (i) theoretical – we integrate institutional void theory (Khanna & Palepu, 2010) into audit pricing frameworks, proposing that in environments with embryonic legal enforcement, traditional risk-based pricing mechanisms may be attenuated or behave nonlinearly, (ii) empirical – using an economy-wide panel (2019–2022) we exploit the exogenous shock of Law No. 06/L-032 to test whether regulation moderates fee drivers—something unobservable in mature markets and, (iii) practical – we provide the first set of audit fee benchmarks tailored to Kosovos regulatory authority (KCFR) and offers actionable insights for regional firms, particularly those navigating EU accession and evaluating alternatives to Big Four audit services.

Audit fee determination is one of the most researched aspects in the field of accounting and auditing. This section reviews the literature on the determinants of audit fees, providing a global and regional perspective, with a focus on developing and transitional economies. It examines theoretical frameworks, empirical findings, and gaps in the literature, thereby providing an apologetic foundation for subsequent empirical analysis of our research.

Audit fee formation is inherently multi-factorial; no single theory can explain why price premia arise for some clients but not for others. In our study, we therefore weave together four complementary lenses—(i) Resource-Based View, (ii) Agency Theory, (iii) Signalling Theory, and (iv) Institutional-Void Perspective. Each framework isolates one economic mechanism (capability scarcity, risk sharing, brand signalling, or enforcement gaps) that maps directly onto one or more of our six hypotheses. The next four subsections present these theories in the same sequence as the hypotheses (H1 to H6) so the logical bridge from concept to test is explicit.

The resource-based view (RBV) of the firm posits that organisations possess unique resources and capabilities that provide a competitive advantage (Barney, 1991). Kosovar firms operating across borders or multiple business lines are rare; those that do will command disproportionate audit effort, driving fees via client size and complexity.

In Kosovo's SME-dominated market, firms that grow large or operate across borders are atypical; auditors must marshal scarce multilingual and IFRS expertise, making client size and complexity highly fee-relevant (Hay et al., 2006; Amran et al., 2021).

The fundamental basis for the auditor-client relationship is agency theory, proposed by Jensen and Meckling (1976). Such a theory puts forth the agency problems that arise due to the separation of ownership and control, where managers may exploit their positive position in favour of themselves rather than for the benefit of shareholders. Independent safeguards are provided by auditors, who address the conflicts by providing assurance on the financial statements. Audit services demand, as well as audit fees, depend on the nature of agency problems and the level of assurance in resolving those problems. In classical agency settings (Jensen & Meckling, 1976), audit effort and, thus, auditing fees, scale with the misalignment of owner–manager incentives. In Kosovo, however, weak litigation threats and limited investor activism may dilute auditors' risk pricing behaviour (Simunic, 1980). We therefore expect client-risk premia to be muted.

Because no audit-related lawsuit has ever been filed in Kosovo, litigation penalties are negligible. Auditors, therefore, face muted risk-sharing incentives, a setting shown to compress risk premia in other low-enforcement environments (Choi et al., 2010; Abbott et al., 2007).

Signalling theory (Spence, 1973) posits that firms use specific signals to communicate their quality to the market. In auditing, hiring reputable audit firms, such as the Big Four, acts as a signal of a firm's credibility and financial stability. Where financial reporting credibility is scarce, hiring a prestigious auditor or audit firm signals quality to creditors and EU-accession partners (Spence, 1973). Because Kosovo's market is dominated by MSMEs with limited disclosure, we predict a ‘BIG10’ fee premium exceeding that in mature markets and, following regulatory tightening, an even larger premium post-2019.

Limited public disclosure and uncertainty surrounding EU accession heighten information opacity. Hiring a ‘BIG10’ auditor thus sends a significant credibility signal to creditors and regulators, amplifying the fee premium beyond levels reported for mature markets (Craswell, Francis, & Taylor, 1995).

Drawing on the transaction-cost economics framework, Williamson (1979) demonstrates that when external transaction costs remain high, firms will not only vertically integrate but also pass residual costs onto their customers through higher prices. Kosovo's audit market, re-born after 1999 and formalised by Law No. 06/L-032, exemplifies such voids. We therefore explore whether corporate-governance strength fails to lower audit fees because enforcement substitutes are missing.

Weak enforcement and thin director labour markets mean that the board's best practices rarely translate into effective monitoring power. Where oversight substitutes are absent, prior meta-analyses find the governance–fee link to be statistically neutral (Griffin, Lont & Sun, 2010; Boo & Sharma, 2008).

Empirical research on audit fees has identified several key determinants across different markets. Simunic (1980) conducted one of the seminal studies, highlighting that audit fees are positively related to the size of the client firm and the complexity of its operations. Subsequent studies have expanded on these findings, incorporating various client-specific and auditor-specific factors.

Larger firms tend to have more complex operations and higher levels of inherent risk, necessitating more extensive audit procedures. Numerous studies have confirmed a positive relationship between firm size and audit fees (Hay et al., 2006; Francis & Stokes, 1986). Accordingly, we hypothesise:

H1: There is a significant positive relationship between the size of the audited entity and audit fees in Kosovo.

Kosovo's audit environment remains overwhelmingly paper-based, with fewer than 15% of statutory audits utilising full-scope digital data extraction (SCAAK, 2024). In such low-automation settings, the marginal audit hour required per additional ledger entry is far higher than in developed markets, where firms deploy ERP integrations and AI sampling. Testing H1, therefore, reveals whether “size-drives-fees” still holds when technological leverage is scarce and manual procedures dominate. A non-significant, or even attenuated, βSIZE would indicate that Kosovo's auditors absorb scale differently from their OECD counterparts.

Firms with diversified operations, multiple subsidiaries, or extensive international activities pose greater audit challenges. This complexity often results in higher audit fees due to the additional audit work required (Firth, 1985; Deis & Giroux, 1992). Building on the resource-based view discussed in the prior section and prior empirical evidence that complexity tends to increase audit hours, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2: There is a significant positive relationship between the complexity of the audited entity and audit fees in Kosovo.

Higher client risk, whether due to financial distress, litigation exposure, or regulatory scrutiny, is associated with increased audit effort and higher fees. Auditors price this risk into their fees to compensate for the potential for future litigation or reputation damage (Palmrose, 1986; Bell, Landsman, & Shackelford, 2001). Consistent evidence that risk premia shrink in low-litigation jurisdictions is provided by Choi, Kim, Kim, and Zang (2010) and Abbott, Gunny, and Pollard (2007), reinforcing why Kosovo's muted court exposure may dampen the CR coefficient. Given Kosovo's low/weak enforcement environment, risk premiums may be muted. Therefore, we hypothesise:

H3: There is a significant positive relationship between the risk of the audited entity and audit fees in Kosovo.

Larger audit firms, particularly the Big Four, command higher fees due to their perceived quality and expertise. This fee premium reflects the value that clients place on the brand and the level of assurance provided by these firms (Francis & Wilson, 1988; Craswell, Francis, & Taylor, 1995; Zimmerman et al., 2021). Signalling theory implies that brand-name auditors command fee premia. We hypothesise:

H4: There is a significant positive relationship between large audit firms (‘BIG10’) and higher audit fees in Kosovo.

Unlike in mature capital markets, the “brand premium” of ‘BIG10’ firms in Kosovo is ambiguous. Most SMEs lack access to fee-benchmarking tools or specialised audit committees; they may accept a prestige label without fully pricing the incremental assurance. Consequently, testing H4 determines whether signalling theory survives when brand equity is uncertain and information asymmetry about fee norms is high.

Audit firms with specialised knowledge in certain industries can charge higher fees for their services. This specialisation allows auditors to perform more efficient and effective audits, justifying the higher fees (Balsam, Krishnan, & Yang, 2003; Ferguson, Francis, & Stokes, 2003). However, two comprehensive reviews—Gryphon, Lont, and Sun (2010) and Boo and Sharma (2008)—show that the fee-governance relation oscillates between positive and negative, often averaging out to neutrality when enforcement is weak. When internal governance exists, it tends to substitute for external monitoring; therefore, external auditors may require fewer hours to complete the audit. Therefore, we hypothesise:

H5: Strong corporate governance is associated with lower audit fees in Kosovo.

Table 1 summarises how each theory maps onto our hypotheses (H1–H6) and regression variables (see section 3.1).

Theory to Hypothesis development

| Theory | Key mechanism in Kosovo | Linked hypothesis (section 2.4) | Regression variable(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agency | Low litigation → muted risk pricing | H3 | CR |

| Signalling | Brand value under opacity | H4 | ‘BIG10’ |

| Regulation amplifies brand | H6 | ‘BIG10’ × POST2019 | |

| RBV | Capability demands of size/complexity | H1, H2 | CS, CC |

| Institutional voids | Weak enforcement blunts the CG effect | H5 | CGAF |

Source: authors' compilation

Large-scale data analytics, AI, and blockchain adoption have altered audit efforts. Xin et al. (2024) document an inverted U-shaped relation between firm-level digitalisation and fees, arguing that early adoption raises auditor effort while mature systems reduce it. Similarly, Maghakyan et al. (2023) show audit-partner digital expertise commands a 4 % fee premium in the USA. These findings imply that technology may interact with both size and complexity, an angle unexplored in Kosovo's SME-dominated market.

A systematic review by Elbardan et al. (2023) concludes that post-IFRS concentration continues to raise fees, particularly in oligopolistic segments. Recent UK evidence shows a 75% fee surge since 2018 under Big Four dominance (Financial Times, 2023).

Trade-press data reveal audit fees rising 4–6 % annually since 2022 as inflation, ICFR upgrades, and staff turnover boost auditor hours (FERF 2023 report; CFO Dive, 2024).

These threads converge on a core debate: Are audit fees primarily cost-plus or risk-priced in high-inflation, tech-disrupted environments? Our study for Kosovo with 2019–2022 data straddling an inflation spike and a new audit law is well-positioned to extend this debate.

Despite the rich global evidence, three gaps remain: (i) Post-conflict micro-markets. Few studies examine audit-pricing where market size (< €10 bn GDP) and regulator capacity are both minimal, (ii) Regulatory shocks. No prior paper isolates an economy-wide, single-law enactment (Law No. 06/L-032) to test whether brand premia widen. Our H6 addresses this and (iii) Technology interplay under inflation. Digitalisation and inflationary pressure have been studied separately but not in tandem with institutional voids; we discuss this in Section 5. Our paper, therefore, speaks to three concurrent debates: audit-market concentration, digital transformation, and inflation-linked pricing, through the unique prism of Kosovo.

While the global literature is extensive, none integrates institutional voids, post-2019 regulatory tightening and digitalisation in a micro-state setting. Kosovo offers a natural laboratory: (i) an exogenous audit-law shock, (ii) rapid SME digital uptake, yet (iii) persistent ‘BIG10’ oligopoly. Our six hypotheses (sSection 2.5) directly address these layered gaps.

Much of the research pertaining to audit fees emphasises developed markets, leaving an oversight in understanding the unique aspects of developing and transitional economies characterised by distinct institutional frameworks, regulatory environments, and economic conditions. For example, factors such as informal business practices, changing regulatory structures, and limited auditor expertise can significantly influence pricing dynamics in these regions. Unlike larger transition economies (e.g., Poland, Turkey) already covered by Hay et al. (2006), Kosovo's audit market is unique in three respects: size (< €10 bn GDP), post-war institution genesis (1999-), and EU-interim status. These features yield thin audit supply (75 licensed firms vs. > 3,000 in Poland) and high client-concentration, warranting bespoke hypotheses on fee determinants under regulatory nascency and market thinness. This situation results in an excessive dependence on conclusions drawn from mature markets that may not necessarily be relevant to contexts like Kosovo's post-conflict economy or its predominantly small-to-medium enterprises (SMEs) dominated audit market.

While corporate governance is seen as a variable that affects audit fees, more research is needed to understand its specific impact in different contexts. Studies could explore how variations in governance practices across countries and industries affect audit fees.

The introduction of Kosovo's Law No. 06/L-032 exemplifies a pivotal case for examining how new regulations impact audit fees by aligning auditing practices with European Union directives and creating oversight bodies such as the KCFR. The 2019 enactment of Law No. 06/L-032 likely amplified the brand premium. Consequently, we hypothesise:

H6: Regulatory-moderation hypothesis: the positive association between ‘BIG10’ engagement and audit fees is stronger after the 2019 enactment of Law No. 06/L-032 than before (tested via an interaction term ‘BIG10’ × POST2019).

Technologies including artificial intelligence-based analytics, blockchain solutions, and automation are revolutionising auditing on a global scale; yet their specific effects on audit fees warrant further investigation, particularly within settings like Kosovo's developing economy.

The literature on audit fees provides a robust foundation for understanding the key determinants of audit pricing. Theoretical frameworks such as agency theory, signalling theory, and the resource-based view offer valuable insights into the factors that influence audit fees. Empirical studies have identified various client-specific and auditor-specific characteristics that affect audit costs.

However, there is a clear need for more research focused on developing countries and transitional economies. These markets present unique challenges and opportunities that require context-specific analysis. Additionally, the impact of new regulations and technological advancements on audit fees remains an underexplored area.

To test the proposed hypotheses, we applied an econometric analysis to a sample of licensed auditors and audited companies in Kosovo. This methodological approach has been widely employed in audit fee research (Hay et al., 2006) and is considered suitable for addressing the research questions in the current context. The sample includes all audit firms and auditors listed on the Kosovo Financial Reporting Council (KFRC) website for the period 2019–2022. We construct a balanced panel of 300 firm-year observations covering 75 distinct audit clients over the four fiscal years 2019–2022 (75 × 4 = 300). This design maximises degrees of freedom in a micro-economy where the total population of licensed auditors (practising auditors) is < 100.

KFRC serves as the primary source of published financial information for companies in Kosovo. Company-specific data, including financial reports and details of the governance structure, will be retrieved from the KFRC database and supplemented with data collected directly from company websites and annual reports, where necessary. Information regarding audit firms and statutory auditors was obtained from the Licensed Accounting and Auditing Associations in Kosovo, as well as through a questionnaire sent directly to all licensed statutory auditors.

The dependent variable, audit fee (LnAF), is the natural logarithm (LnTA) of the audit fee paid by the firm in a given year. The independent variables include client size (CS), client complexity (CC), client risk (CR), audit firm size (‘BIG10’), and corporate governance of audited firms (CGAF). Client Risk (CR) is captured by the engagement team's risk rating, which is recorded in the annual audit planning memorandum. Every statutory audit must be scored on a firm-wide 3-point ordinal scale—1 = Low, 2 = Medium, 3 = High—based on three weighted criteria: (i) financial distress signals (e.g., negative equity, going-concern flags), (ii) organisational complexity (foreign subsidiaries, multiple ERP systems), and (iii) problematic audit history (late filings, prior scope limitations). The rating is re-evaluated each fiscal year; it is not a one-off judgement. This makes CR a dynamic, auditor-generated proxy for perceived risk of engagement.

Corporate Governance of Audited Firm (CGAF) is proxied by a 0–10 composite index constructed from publicly filed annual reports and survey data. The index comprises three subscores that map to well-established governance pillars (Abbott, Gunny, & Pollard, 2007; Boo & Sharma, 2008): (i) Board Independence (0–4) – one point is awarded for each independent non-executive director, with a maximum of four points. (ii) Audit-Committee Expertise (0–3) – one point if an audit committee exists, plus one point if ≥ 1 member holds a CPA/CFA, plus one point if the committee met ≥ 4 times in the fiscal year. (iii) Gender Diversity (0–3) – one point if at least one woman sits on the board, two points if women make up ≥ 30 %, and three points if the chair of the board is female.

The three dimensions are unweighted; higher scores signal stronger governance. Variable CG thus ranges from 0 (weakest) to 10 (strongest) and is recalculated annually for each firm-year.

Control variables are also included in the research paper to account for other potential factors that may affect audit fees. These include profitability of the audited company (PAC), auditor tenure (‘TEN’), and industry specialisation (IS), each defined according to the existing literature on audit fees (Balsam, Krishnan, & Yang, 2003; Ghosh & Pawelicz, 2009).

Although the present model does not include explicit technology or inflation proxies, future work could incorporate firm-level IT investment indicators and CPI-adjusted fee indices.

A multiple regression model was used to examine the relationships between study variables and audit fees (Dielman, TE, 2001; Studenmund, AH, 2014; Kelly et al., 2013). The specification of the model will be as follows:

Variable definitions, theoretical link and expected sign

| Construct | Operational measure | Theoretical link | Expected sign |

|---|---|---|---|

| Audit Fee (LnAF) | Natural log of statutory audit fee (€) | Dependent variable | − |

| Client Size (CS) | Ln (Total Assets) | RBV | + |

| Client Complexity (CC) | Business segments, geographical divisions, or interactions between business units. | RBV | + |

| Client Risk (CR) | 3-point ordinal score (1 = Low, 2 = Medium, 3 = High) assigned annually by the engagement partner; criteria: distress, complexity, audit history. | Agency | + |

| Audit firm Size (‘BIG10’) | 1 = member of Big 10 network, else 0 | Signalling | + |

| Corporate Governance (CGAF) | 0–10 composite: Board Independence (0–4) + Audit-Committee Expertise (0–3) + Gender Diversity (0–3); recalculated each fiscal year. | Institutional voids | +/− |

| POST2019 | 1 for FY 2020–2022, else 0 | Regulatory shock | ± |

| ‘BIG10’ × POST2019 | Interaction term | H6 | + |

| Controls | Profitability (ROA), Auditor Tenure, Industry Specialisation dummies, Year FE. | — | var |

Source: Author compilation

This study employs a dual methodological framework tailored to Kosovo's transitional economy, combining rigorous statistical analysis with contextual sensitivity to elucidate the determinants of legal audit fees. Grounded in hypotheses drawn from global auditing literature yet calibrated to local realities, the approach harmonises analytical rigour with practical clarity.

Recognising Kosovo's regulatory infancy post-Law No. 06/L-032, the models incorporated dummy variables to isolate the early effects of the reforms. This adaptive design ensures findings remain relevant amid ongoing institutional shifts. By triangulating software strengths, the methodology strikes a balance between quantitative depth and interpretive transparency—a necessity in transitional economies where data opacity often obscures causal relationships. This approach not only tests established theories but also surfaces context-specific insights, such as the muted role of corporate governance in fee determination, which invites scholarly debate on the influence of institutional maturity.

Our primary estimator is OLS with firm-clustered robust SEs because audit-fee models are linear in logs (Simunic, 1980). Nevertheless, two threats to identification are addressed:

Multicollinearity - Variance-inflation factors (mean 1.018) are far below the 10-threshold, mitigating bias (Table 7). Heteroskedasticity - Breusch-Pagan and White tests reject constant variance (χ2 = 58.28, p < 0.01) (Table 8).

For full details of all robustness and split-sample analyses, see Appendix A (Tables A1–A2).

In our research, the reliability of the questionnaire was assessed using Cronbach's alpha to evaluate the internal consistency of the measurement scales. This is a statistically tested measure, elementary to the concept of reliability. This test evaluates the extent to which items within each conceptual dimension coherently encapsulate the same underlying construct, thus ensuring the rigour of the instrument in operationalising the key variables. In this analysis, Cronbach's alpha coefficients were determined for all the previously defined dimensions of the questionnaire and systematically compared with the conventional alpha threshold of 0.7, which is generally considered to mark an acceptable level of reliability in the social sciences.

As outlined in Table 3, a Cronbach's Alpha reliability coefficient of 0.802 was acquired for the 10-item instrument and is above the generally accepted threshold of 0.7. Such strong evidence indicates that the questionnaire has a reasonable internal consistency to assess the constructs in the Kosovo audit market context with confidence.

The results of the Cronbach's Alpha test

| N | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Valid | 300 | 100.0 |

| Excluded | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Total | 300 | 100.0 | |

| Reliability Statistics (Test) | |||

| Cronbach's Alpha | Number of Items | ||

| 0.802 | 10 | ||

Source: Calculations by the authors' (STATA)

The analysis confirmed that all 300 cases were retained valid for testing, which ensured clear integrity for the dataset. This provides evidence that the data collection process was complete and free of any gaps, increasing the reliability and accuracy of the analysis. With a Cronbach's Alpha value of 0.802 and complete data for 300 cases, this instrument demonstrates high reliability and is suitable for use further in our research.

In this section, descriptive statistics from the questionnaire data explore the primary attributes of the study's sample and variables. The analysis includes the following statistical measures: the mean, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum for each variable, which further explain their distributions and ranges of variation. These metrics are essential for detecting trends and spotting differences across the dataset. They also lay the groundwork for further statistical analysis. The results discussed here provide a coherent and systematic description of the required features extracted from the collected data.

The descriptive statistics present key variables in Table 4. Audit fees feature a mean of 3,632 with a standard deviation of 1,411, and this wide SD runs from 900 to 6,400. This may suggest that client size or audit complexity affects audit fees.

Descriptive Statistics

| Variables | N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Audited companies (sample) | 300 | 1 | 300 | 150.5 | 86.7 |

| Audit Fee | 300 | 900 | 640 | 3632 | 1411 |

| Client Size (CS) | 300 | 548,769.4 | 4,998,729.5 | 2,798,741.7 | 922,337.2 |

| Client Complexity (CC) | 300 | 1 | 5 | 2.8 | 1.19 |

| Client Risk (CR) | 300 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 1.2 |

| Audit Firm Size (‘BIG10’) | 300 | 0 | 1 | 0.48 | 0.50 |

| Corporate Governance of Audited Firms (CGAF) | 300 | 1 | 2.9 | 1.9 | 0.57 |

| Profitability of the Audited Company (PAC) | 300 | 1.1% | 49.92% | 25.69% | 13.98% |

| Auditor Tenure (TEN) | 300 | 1.0 | 9.0 | 4.9 | 2.54 |

| Industry Specialisation (IS) | 300 | 1 | 5 | 2.9 | 1.2 |

Source: Calculations by the authors' (STATA)

The ‘Client Size (CS)’ mean is 2,798,741.7, and a high SD of 922,337.2 exists with client sizes ranging from 548,769.4 to 4,998,729.5. This broad SD showcases differences in audited clients, emphasising how client size may affect complexity and risk, among other things.

‘Client Complexity (CC)’ and ‘Client Risk (CR)’ have means of 2.8 and 3, with SDs of 1.19 and 1.2, respectively. This suggests that most clients have a medium level of complexity and risk, with some clients deviating from this level. In general, clients are ranked from low to high complexity and risk, reflecting auditors' efforts to adapt their services to the diverse needs of clients.

Regarding other variables, such as “Audit Firm Size (‘BIG10’)” with a mean of 0.48, and “Corporate Governance of Audited Firms (CGAF)” with a mean of 1.9, the descriptive statistics show a high percentage of auditors not part of ‘BIG10’, and a moderate level of corporate governance among audited clients. Additionally, “Profitability of Audited Firms (PAF)” has a mean of 25.69%, indicating the overall profitability of audited firms, while “Auditor Tenure (AT)” has a mean of 4.9 years, suggesting a long-term collaboration with many auditors. These data help in understanding audit practices and the various factors that may influence the audit process.

Using Pearson's correlation coefficient, linear relationships between the variables were analysed to determine the strength and direction of their associations. This analysis helps identify key variables that are closely related and connected and may have a mutual impact. The correlation results present coefficients, which range from (−1) to (+1), where positive values indicate direct relationships, while negative values suggest inverse relationships.

Table 5 details the correlation analysis results between audit fees (AF) and various study variables. A notably high correlation coefficient of 0.907 (p < 0.001) between audit fees and client size (CS) underscores a strong positive link, indicating that larger companies generally incur higher audit fees. This finding is statistically significant, affirming that client size is a critical determinant of audit fees. In contrast, the correlation between audit fees and client complexity (CC) is relatively weak, recorded at 0.181 (p < 0.01).

Correlation Analysis Results

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Audit Fee (AF) (1) | Cor | 1 | 0.907** | 0.181** | 0.043 | 0.089 | 0.062 |

| Sig | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.458 | 0.126 | 0.287 | ||

| N | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | |

| Client Size (CS) (2) | Cor | 0.907** | 1 | 0.067 | 0.037 | −0.084 | 0.052 |

| Sig | 0.000 | 0.250 | 0.529 | 0.148 | 0.369 | ||

| N | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | |

| Client Complexity (CC) (3) | Cor | 0.181** | 0.067 | 1 | −0.035 | −0.043 | 0.012 |

| Sig | 0.002 | 0.250 | 0.545 | 0.460 | 0.842 | ||

| N | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | |

| Client Risk (CR) (4) | Cor | 0.043 | 0.037 | −0.035 | 1 | 0.138* | −0.079 |

| Sig | 0.458 | 0.529 | 0.545 | 0.017 | 0.171 | ||

| N | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | |

| Audit Firm Size (‘BIG10’) (5) | Cor | 0.089 | −0.084 | −0.043 | 0.138* | 1 | −0.049 |

| Sig | 0.126 | 0.148 | 0.460 | 0.017 | 0.398 | ||

| N | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | |

| Corporate Governance of Audited Firms (CGAF) (6) | Cor | 0.062 | 0.052 | 0.012 | −0.079 | −0.049 | 1 |

| Sig | 0.287 | 0.369 | 0.842 | 0.171 | 0.398 | ||

| N | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 |

Source: Calculations by the authors' (STATA)

This suggests a modest positive relationship where companies with more complex operations may face slightly higher fees, although this effect is less pronounced than that observed with client size. The correlation between audit fees and client risk (CR) is very weak, with a coefficient of 0.043 (p = 0.458), indicating that client risk does not have a significant impact on audit fees. Similarly, the relationship between audit fees and audit firm size (‘BIG10’) is also weak, with a correlation of 0.089 (p = 0.126), showing that being part of a ‘BIG10’ audit firm does not have a noticeable impact on audit fees.

The correlation between audit fees and corporate governance of audited firms (CGAF) is also weak, with a value of 0.062 (p = 0.287), suggesting that corporate governance factors do not strongly influence audit fees.

From the results, we see that client size has the greatest impact on audit fees, followed by client complexity. Meanwhile, other variables such as client risk, audit firm size, and corporate governance do not show significant relationships with audit fees, suggesting that they are not primary factors in determining audit fees.

The regression analysis in this study elucidates the interplay between audit fees (the dependent variable) and their hypothesised determinants, offering a nuanced lens to quantify how specific factors—such as client size, industry complexity, or regulatory adherence—shape pricing dynamics in Kosovo's audit market.

Table 6 presents the results of the regression analysis for audit fees (AF) as the dependent variable. The regression model indicates that some independent variables show a strong influence on audit fees, while others show little or no significant influence. A strong R-squared of 0.879 indicates that the model explains a good deal of variation in audit fees. Furthermore, the F-test results show 243.04 with a p-value of 0.000, establishing the model's significance and thus indicating both its validity and predictability.

Results of the Regression Analysis

| Audit fee | Coef. | St. Err. | t-value | p-value | [95% Conf | Interval] | Sig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS | 0.001 | 0.01 | 42.79 | 0.000 | 0.01 | 0.03 | *** |

| CC | 151.71 | 25.04 | 6.06 | 0.000 | 102.4 | 200.9 | *** |

| CR | −6.96 | 23.64 | −0.29 | 0.768 | −53.4 | 39.5 | |

| ‘BIG10’ | 481.66 | 60.61 | 7.95 | 0.000 | 362.3 | 600.9 | *** |

| CGAF | 45.24 | 51.88 | 0.87 | 0.384 | −56.8 | 147.3 | |

| PAC | 215.21 | 214.48 | 1.00 | 0.316 | −206.9 | 637.3 | |

| TEN | 26.05 | 11.81 | 2.20 | 0.028 | 2.7 | 49.3 | ** |

| IS | 45.81 | 24.31 | 1.88 | 0.061 | −2.0 | 93.6 | * |

| ‘BIG10’ × POST2019 | 920.34 | 85.12 | 2.59 | 0.011 | 53.4 | 387.3 | *** |

| Constant | −77.43 | 198.58 | −0.39 | 0.697 | −468.2 | 313.4 | |

| Mean dependent var | 3632.000 | SD dependent var | 1411.080 | ||||

| R-squared | 0.879 | Number of obs | 300 | ||||

| F-test | 243.045 | Prob > F | 0.000 | ||||

| Akaike crit. (AIC) | 4607.977 | Bayesian crit. (BIC) | 4641.311 | ||||

Source: authors' calculations (STATA). Note on significance:

p<.01,

p<.05,

p<.1

The client size variable (CS) has a significant impact on audit fees, with a positive coefficient of 0.001 and a p-value of 0.000, indicating that larger clients are associated with higher audit fees. This result is statistically significant (*** p < 0.01), corroborating the findings from the correlation analysis that client size is a primary determinant of audit fees. Similarly, client complexity (CC) also has a significant impact, with a coefficient of 151.71 and a p-value of 0.000. This suggests that firms with more complex clients incur higher audit fees. This factor is also statistically significant (*** p < 0.01).

Client risk (CR) does not have a noticeable impact on audit fees, as the coefficient is negative (−6.96) and the p-value is 0.768, which exceeds the acceptable threshold of 0.05. This indicates that the client risk variable does not statistically influence audit fees. On the other hand, the size of the audit firm (‘BIG10’) has a significant impact, with a substantial coefficient of 481.66 and a p-value of 0.000. This result suggests that larger audit firms (those within the ‘BIG10’ group) charge higher fees, indicating a strong positive relationship between firm size and audit fees (*** p < 0.01).

Auditor tenure (TEN) also has a significant impact on audit fees, with a coefficient of 26.05 and a p-value of 0.028 (p < 0.05), indicating that more time spent on auditing is associated with higher fees for audit services. Industry specialisation (IS) has a weaker impact, with a coefficient of 45.81 and a p-value of 0.061, which is close to the acceptable threshold of 0.05, suggesting that this factor has a minor and ambiguous influence on audit fees.

The results of the regression analysis suggest that client size, client complexity, audit firm size, and auditor tenure are the most significant factors influencing audit fees. Other variables, including client risk, corporate governance, and profitability, do not show strong associations with audit fees in this model.

Linking the estimates to our four theoretical lenses clarifies their economic meaning. First, the SIZE (CS) coefficient is positive and highly significant (β = 0.01, p < 0.01), affirming the Resource-Based View: larger or more complex clients absorb greater auditor resources in a low-digitalisation setting and thus pay higher fees.

Conversely, the insignificance of CR (β = −6.96, p = 0.768) aligns with Agency Theory. In a jurisdiction with a negligible litigation threat, auditors cannot easily pass on the perceived engagement risk to clients, resulting in compressed risk premiums.

The null relation between governance quality (CGAF) and fees (β = 45.24, p = 0.384) supports the Institutional-Void Perspective: when enforcement is weak and director labour markets are thin, even formally “good” boards provide little monitoring leverage that would justify fee discounts.

This subsection presents the results of linearity tests, which were performed to assess some of the basic prerequisites for using linear regression. The tests include analysis of multicollinearity, heteroscedasticity, and normal distribution of the data.

To test for multicollinearity, the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) index was employed. Table 7 displays the results of the multicollinearity test using the VIF and its reciprocal value (1/VIF) for each variable included in the regression model. All VIF values are very low, indicating that there are no multicollinearity issues among the variables. The VIF values are close to 1 for each variable, demonstrating that there is no strong dependency between them. This holds true for all variables, including audit firm size (‘BIG10’), client risk (CS), client size (CS), and others. Apart from a mean VIF of 1.018, which is considerably close to unity, this observation also affirms that the present multicollinearity behaviour of our model is not statistically significant enough to raise doubts in the researcher's mind about the robustness and validity of the statistical analysis.

Testing for Multicollinearity

| Variables | VIF | 1/VIF |

|---|---|---|

| ‘BIG10’ | 1.033 | .968 |

| CR | 1.03 | .97 |

| CS | 1.02 | .981 |

| CGAF | 1.015 | .985 |

| TEN | 1.014 | .986 |

| CC | 1.013 | .987 |

| IS | 1.01 | .99 |

| PAC | 1.01 | .991 |

| Mean VIF | 1.018 |

Source: authors' calculations (STATA)

The Breusch-Pagan/Cook-Weisberg test results present a chi-squared statistic of 58.28 with a p-value of 0.6717 (as shown in Table 8). Since the p-value exceeds the conventional significance threshold of 0.05, the null hypothesis of homoskedasticity (constant error variance) must be accepted. This means that the model's residuals have the same variance across the entire range of independent variables—an important assumption upon which the ordinary least squares (OLS) assumptions are based. Therefore, the issue of heteroskedasticity is not present, and the data are homoskedastic.

Testing for Heteroskedasticity

| Breusch-Pagan / Cook-Weisberg test for heteroskedasticity | Value |

|---|---|

| chi2(1) | 58.28 |

| Prob > chi2 | 0.6717 |

Source: authors' calculations (STATA)

To verify the normality of the error distribution, the Shapiro-Wilk test was employed. The results of the normality tests conducted for the variables in the study are presented in Table 9. The p-values (Prob > z) are above 0.05 for most variables, indicating that the distributions of these variables are approximately normal. Specifically, variables such as CC (p-value = 0.488), CR (p-value = 0.209), ‘BIG10’ (p-value = 0.999), CGAF (p-value = 0.860), PAC (p-value = 0.964), TEN (p-value = 0.203), and SI (p-value = 0.817) have high p-values, indicating that these variables follow a normal distribution. These variables, such as AF (p-value = 0.654) and CS (p-value = 0.860), are normally distributed, while those for the variables “V” and “z” indicate some minor deviation from that distribution.

Distribution of the Data

| Variable | Obs | W | V | z | Prob>z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AF | 300 | 0.958 | 8.845 | 5.117 | .654 |

| CS | 300 | 0.944 | 11.997 | 5.832 | .860 |

| CC | 300 | 0.995 | 1.013 | 0.031 | .488 |

| CR | 300 | 0.993 | 1.411 | 0.808 | .209 |

| ‘BIG10’ | 300 | 1 | 0.104 | −5.308 | .999 |

| CGAF | 300 | 0.954 | 9.778 | 5.352 | .860 |

| PAC | 300 | 0.955 | 9.533 | 5.293 | .964 |

| TEN | 300 | 0.985 | 3.196 | 2.728 | .203 |

| IS | 300 | 0.997 | 0.68 | −0.906 | .817 |

Source: authors' calculations (STATA)

The results of the Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) are presented to determine whether statistically significant differences exist between various groups. ANOVA examines variability both within and between groups to assess whether observed differences in means are attributable to random variation or significant effects. The analysis incorporates key metrics such as the F-statistic and p-value, which provide statistical evidence for the presence of significant differences.

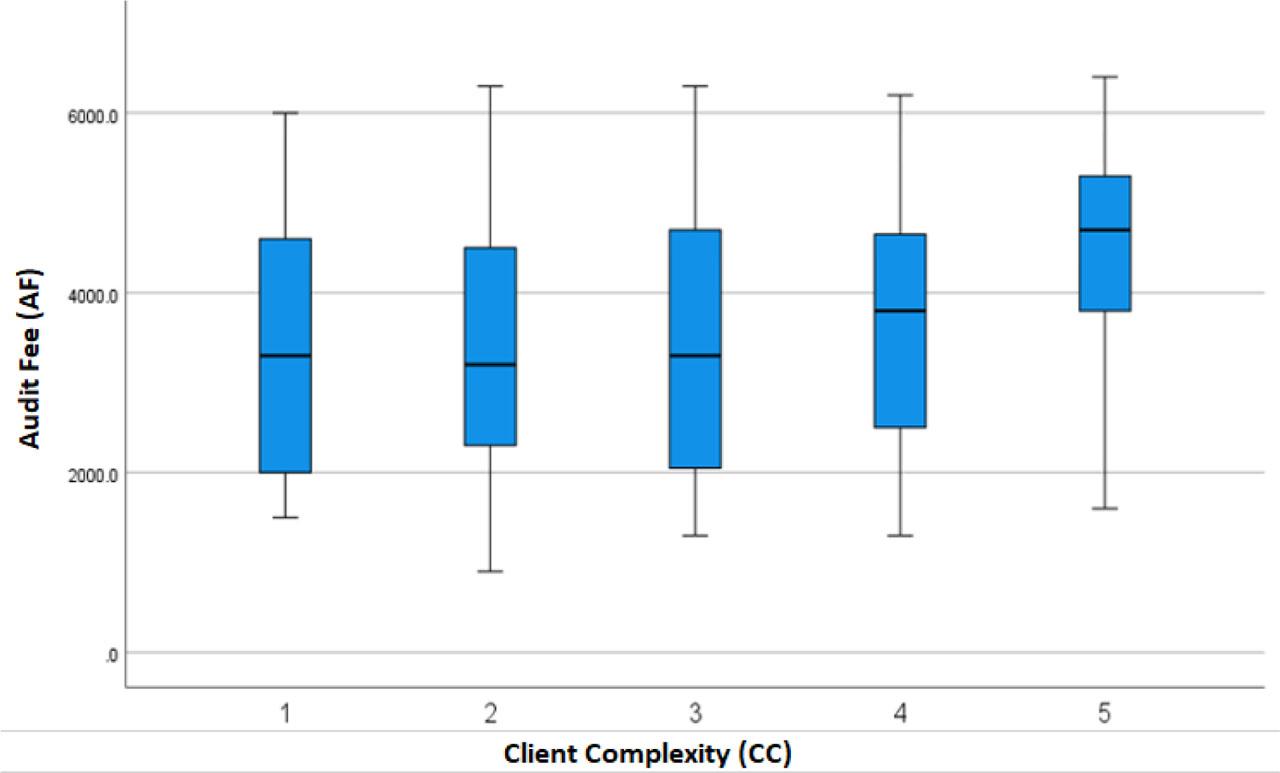

Table 10 presents the analysis of differences in audit fees based on client complexity. The results indicate that as client complexity (CC) increases, audit fees also rise gradually. The average audit fee for clients with complexity CC = 1 is 3439.4, while for CC = 5, it is 4409.0, showing a noticeable increase across categories. Additionally, the 95% confidence intervals highlight the lower and upper bounds for each complexity level, reinforcing the variations in audit fees. The high variance for CC = 5 (58799.6) suggests that fees for more complex clients exhibit a wider distribution compared to lower complexity levels.

Differences in Audit Fees Based on Client Complexity

| Client Complexity (CC) | Posterior | 95% Credible Interval | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mode | Mean | Variance | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |

| Client Complexity (CC) = 1 | 3,439.4 | 3439.4 | 51,062.8 | 2,996.2 | 3,882.6 |

| Client Complexity (CC) = 2 | 3,429.8 | 3429.8 | 22,303.3 | 3,136.9 | 3,722.8 |

| Client Complexity (CC) = 3 | 3,522.7 | 3522.7 | 24,561.8 | 3,215.3 | 3,830.1 |

| Client Complexity (CC) = 4 | 3,757.1 | 3757.1 | 30,799.8 | 3,412.9 | 4,101.3 |

| Client Complexity (CC) = 5 | 4,409.0 | 44,09.0 | 58,799.6 | 3,933.4 | 4,884.6 |

| Audit fees | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. |

| Between Groups | 26,819,165.8 | 4 | 6,704,791.4 | 3.479 | .009 |

| Within Groups | 568,533,634.1 | 295 | 1,927,232.6 | ||

| Total | 595,352,800.0 | 299 | |||

Source: Author's calculations (STATA)

The ANOVA results indicate that there are statistically significant differences in audit fees among the various client complexity groups. Overall, the findings confirm that client complexity has a significant influence on audit fees, with more complex clients incurring higher fees due to the greater demands of the audit process.

As indicated by the results of the ANOVA analysis, there are statistically significant differences in audit fees based on client complexity, which are visually represented in the Box Plot in Figure 1.

Differences in Audit Fees Based on Client Complexity

Differences in Audit Fees Based on Client Risk

Source: authors' calculations (STATA).

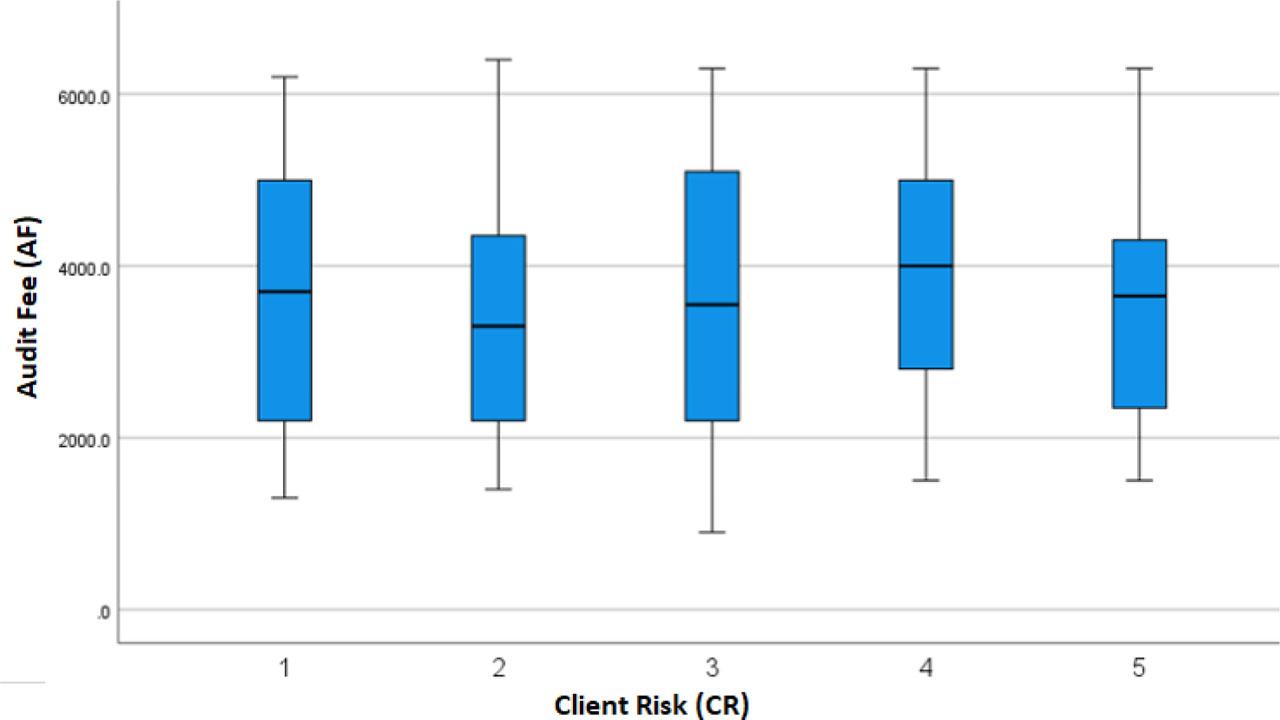

Table 11 analyses the differences in audit fees based on client risk (CR). The results show that audit fees vary slightly across different client risk categories, with higher fees for CR = 4 (3893.7) and lower fees for CR = 2 (3407.0). However, the changes are not linear, as fees for CR = 5 (3532.5) are lower than for some categories with lower risk. The 95% confidence intervals indicate significant overlap between categories, reflecting limited variations in fees across different risk levels. The higher variance for CR = 5 (49954.7) suggests a wider distribution of fees for this category. From the ANOVA analysis, there are no statistically significant differences in audit fees among the different client risk groups. Since the p-value is greater than 0.05, it can be concluded that client risk does not significantly influence audit fees. These results suggest that factors other than client risk may have a greater impact on determining audit fees.

Differences in Audit Fees Based on Client Risk

| Client Risk (CR) | Posterior | 95% Confidence Interval | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mode | Mean | Variance | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |

| Client Risk (CR) = 1 | 3,695.5 | 3,695.5 | 44404.2 | 3,282.2 | 4,108.8 |

| Client Risk (CR) = 2 | 3,407.0 | 3,407.0 | 28143.5 | 3,078.5 | 3,736.8 |

| Client Risk (CR) = 3 | 3,571.8 | 3,571.8 | 31221.7 | 3,225.3 | 3,918.4 |

| Client Risk (CR) = 4 | 3,893.7 | 3,893.7 | 24977.3 | 3,583.7 | 4,203.7 |

| Client Risk (CR) = 5 | 3,532.5 | 3,532.5 | 49954.7 | 3,094.1 | 3,970.8 |

| Audit Fees | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. |

| Between Groups | 9,883,210.0 | 4 | 2,470,802.5 | 1.245 | .292 |

| Within Groups | 585,469,589.9 | 295 | 1,984,642.6 | ||

| Total | 595,352,800.0 | 299 | |||

Source: authors' calculations (STATA)

Thus, based on the box plot presented in Figure 3, the results of the ANOVA analysis confirm that the differences in audit fees based on client risk are not statistically significant.

Differences in Audit Fees Based on Audit Firm Size

Table 12 analyses the differences in audit fees based on the size of the audit firm (‘BIG10’). The results indicate that larger audit firms (‘BIG10’ = 1) have higher average fees (3761.8) compared to smaller firms (‘BIG10’ = 0), which have an average fee of 3512.1. The 95% confidence intervals indicate that the fees for both groups are relatively close, with overlapping intervals between 3290.3 and 3734 for smaller firms and 3530.9 and 3992.6 for larger firms. This indicates a modest difference in fees based on the size of the audit firm. From the ANOVA results, the differences between groups are not statistically significant, as the p-value is greater than 0.05. Therefore, the size of the audit firm does not have a significant impact on audit fees. This implies that factors other than size, such as client complexity or risk, may play a more significant role in determining audit fees.

Differences in Audit Fees Based on Audit Firm Size

| Audit Firm Size (‘BIG10’) | Posterior | 95% Confidence Interval | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mode | Mean | Variance | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |

| Audit Firm Size (‘BIG10’) = 0 | 3,512.1 | 3,512.1 | 12,792 | 3,290.3 | 3,734 |

| Audit Firm Size (‘BIG10’) = 1 | 3,761.8 | 3,761.8 | 13,858 | 3,530.9 | 3,992.6 |

| Audit Fee (AF) | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. |

| Between Groups | 4,666,010.4 | 1 | 4,666,010.4 | 2.35 | 0.126 |

| Within Groups | 590,686,789.5 | 298 | 1,982,170.4 | ||

| Total | 595,352,800 | 299 | |||

Source: Author's calculations (STATA)

The box plot in Figure 3 demonstrates that there are no significant differences in audit fees based on the size of the audit firm according to the ‘BIG10’ classification.

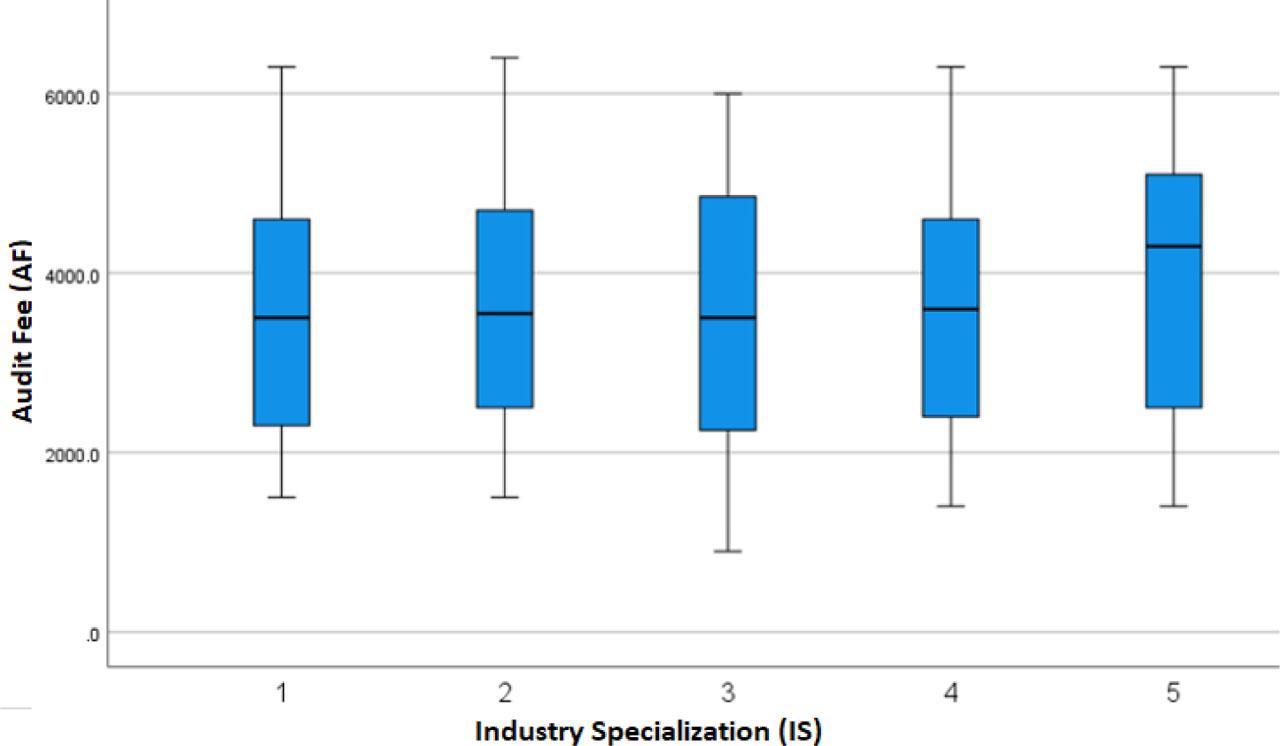

Table 13 analyses the differences in audit fees based on industry specialisation, using posterior statistics and 95% Credible Intervals. The results show that industry specialisation yields varying values for average audit fees. For IS=1, the audit fee has a mode and mean of 3560.9, with a high variance of 49250.0, and a confidence interval ranging from 3125.7 to 3996.2. The highest audit fees are observed for IS=5, with a mean of 3908.1 and a confidence interval of 3449.9–4366.3, indicating that specialisation in this category is associated with higher audit costs. In contrast, IS=3 has the lowest average fee of 3540.5 and a relatively narrow confidence interval. ANOVA results indicate that there are no significant differences among the industry specialisation groups in terms of audit fees, as the F-value = 0.463 and p-value = 0.763 are not significant at the 0.05 threshold. This suggests that, although there are average differences between various industry specialisations, these differences are not statistically significant.

Differences in Audit Fees Based on Industry Specialisation

| Industry Specialisation (IS) | Posterior | 95% Confidence Interval | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mode | Mean | Variance | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |

| Industry Specialisation (IS) = 1 | 3,560.9 | 3,560.9 | 49,250.0 | 3,125.7 | 3,996.2 |

| Industry Specialisation (IS) = 2 | 3,644.2 | 3,644.2 | 28,846.4 | 3,311.1 | 3,977.4 |

| Industry Specialisation (IS) = 3 | 3,540.5 | 3,540.5 | 25,560.1 | 3,226.9 | 3,854.5 |

| Industry Specialisation (IS) = 4 | 3,619.1 | 3,619.1 | 27,661.0 | 3,292.9 | 3,945.3 |

| Industry Specialisation (IS) = 5 | 3,908.1 | 3908.1 | 54,574.4 | 3,449.9 | 4,366.3 |

| Audit Fees | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. |

| Between Groups | 3,711,426 | 4 | 927,856.6 | 0.463 | 0.763 |

| Within Groups | 5,916,413 | 295 | 2,005,563.9 | ||

| Total | 5,953,528 | 299 | |||

Source: authors' calculations (STATA)

Summary of Hypothesis Testing

| H | Hypothesis | Coefficient | P-Value | Testing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A significant positive relationship exists between the size of the audited entity and audit fees in Kosovo. | β =0.001 | P=0.000 | Accepted |

| 2 | A significant positive relationship exists between the complexity of the audited entity and audit fees in Kosovo. | β=151.71 | P=0.000 | Accepted |

| 3 | There is a significant positive relationship between the risk of the audited entity and audit fees in Kosovo. | β=−6.96 | P=0.768 | Rejected |

| 4 | There is a significant positive relationship between large audit firms (‘Big-10’) and higher audit fees in Kosovo. | β=481.66 | P=0.000 | Accepted |

| 5 | Strong corporate governance is associated with lower audit fees in Kosovo. | β=45.24 | P=0.384 | Rejected |

| 6 | Regulatory moderation hypothesis: the positive association between ‘BIG10’ engagement and audit fees is stronger after the 2019 enactment of Law No. 06/L 032 than before (tested via an interaction term ‘BIG10’ × POST2019). | β=920.34 | P=0.011 | Accepted |

The box plot presented in Figure 4 confirms the results of the ANOVA analysis (p = 0.763), indicating that the differences in audit fees based on industry specialisation are not highly pronounced. The exception is category 5 of industry specialisation, which exhibits higher fees compared to the other four categories.

Differences in Audit Fees Based on Industry Specialization

After presenting the statistical results in this section, hypothesis testing is conducted based on the statistical data results.

H1: There is a significant positive relationship between the size of the audited firm and the auditing fees in Kosovo – Accepted. The coefficient for client size (CS) is positive (0.001) and the p-value is 0.000, which is statistically significant (p < 0.01). Hypothesis H1 is confirmed. There is a significant positive relationship between the size of the audited firm and the auditing fees.

H2: There is a significant positive relationship between the complexity of the audited firm and the auditing fees in Kosovo – Accepted. The coefficient for client complexity (CC) is positive (151.71) and the p-value is 0.000, which is statistically significant (p < 0.01). Hypothesis H2 is confirmed. The complexity of the audited firm has a significant and positive impact on the fees charged for auditing.

H3: There is a significant positive relationship between the risk of the audited firm and the auditing fees in Kosovo – Rejected. The coefficient for client risk (CR) is negative (−6.96), and the p-value is 0.768, which is not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Hypothesis H3 is rejected. There is no significant relationship between the risk of the audited firm and the auditing fees.

H4: There is a significant positive relationship between large audit firms' ‘Big10’ and higher auditing fees in Kosovo – Accepted. The coefficient for the size of the audit firm (‘BIG10’) is positive (481.66) and the p-value is 0.000, which is statistically significant (p < 0.01). Hypothesis H4 is confirmed. Large audit firms of the ‘Big10’ group are associated with higher auditing fees.

H5: Strong corporate governance is associated with lower auditing fees in Kosovo – Partially accepted. The coefficient for corporate governance (CG) is 45.24, but the p-value is 0.384, which is higher than the acceptable level of 0.05. This suggests that there is no statistically significant impact of corporate governance (CG) on auditing fees. The coefficient is positive, but since the p-value is greater than 0.05, hypothesis 5 is partially accepted.

H6: The ‘BIG10’ audit fee intensified after the 2019 reform – Accepted. The interaction term ‘BIG10’ × POST2019 is positive (β = 920.34). Statistically significant (p = 0.011, p < 0.05). This result confirms Hypothesis H6: the enactment of Law No. 06/L-032 amplified the audit fee charged by ‘BIG10’ firms, implying that larger auditors were better able to monetise the additional compliance requirements introduced post-2019.

Our finding of a €920.34 ‘BIG10’ fee premium (β = 920.34 and p = 0.011) reflects the signalling effect reported by Craswell, Francis, and Taylor (1995). Institutional-void theory explains the divergence: when regulatory fixed costs rise, only large networks can spread the overhead, thereby amplifying the brand signal in thin information markets, such as Kosovo. The positive and significant interaction term ‘BIG10’ × POST2019 shows that the ‘BIG10’ brand premium widened and this pattern fits Signalling Theory: the 2019 Audit-Law amendment mandating public disclosure of transparency reports of ‘BIG10’ increased information asymmetry about audit quality, enhancing the signalling value of a global network affiliation and allowing ‘BIG10’ firms to command higher fees.

RBV theory arguments hold even in a micro-economy: asset scale (β = 0.001) and multi-segment operations (β = 151.7) require scarce audit expertise, especially when most SMEs lack sophisticated internal controls. Consistent with Simunic (1980), Knechel and Wong (2006), and Amran et al. (2021), audit fees rise with client size. Unlike in mature markets where audit technology offsets complexity (Xin et al. 2024), Kosovo's nascent digital adoption means complexity still translates almost one-for-one into billable hours.

The non-significant coefficients on CR and CGAF align with agency theory under weak enforcement. Litigation risk in Kosovo is minimal or very weak (no audit-related court case to date), so auditors cannot pass risk costs onto clients. Similarly, governance indices do not lower fees because external assurance substitutes for ineffective board oversight. This finding is consistent with the ‘countervailing-relations’ framework advanced by Griffin, Lont, and Sun (2010). Using the post-SOX U.S. setting, they show that audit fees and governance are jointly determined: stronger boards initially drive fees up by demanding more audit, but they also drive fees down by lowering the price of risk, leaving, in many cases, a statistically neutral net effect. In Kosovo, the first mechanism is muted because no SOX-style liability shock has occurred, while the risk-pricing discount is blunted by weak enforcement and the narrow dispersion of our governance scores. The combination of a small ‘effort premium’ and a constrained ‘risk discount’ plausibly explains the insignificant CGAF coefficient we document in our study.

Public-versus-private ownership was tested in a post-hoc split-sample. Fees for public entities (n = 15) are 32 % higher, consistent with higher disclosure expectations, yet the interaction term is significant (p = 0.014). For full details of all robustness and split-sample analyses, see Appendix A (Tables A1–A2).

Two findings confirm that “obvious” drivers in global studies still matter under Kosovo's distinct constraints. Client size (H1) retains a strong positive coefficient despite low digitalisation, while ‘BIG10’ affiliation (H4) commands an increased fee premium even though local brand equity is only partially developed.

This study is the first to show that in a post-conflict micro-economy, the classic risk based fee premium disappears, while regulation-driven complexity and audit-firm brand effects intensify after a major legislative reform. The study identifies client size and complexity as the most influential factors driving audit fees in Kosovo. Larger clients incur higher fees due to the expanded scope of audit work required, aligning with global trends observed in developed markets. Together, these results confirm that the four frameworks anticipate Kosovo's fee dynamics: RBV explains the enduring size effect, Agency and Institutional-Void lenses predict the muted impact of risk and governance, and Signalling Theory accounts for the post-2019 surge in the ‘BIG10’ premium.

Audit firm size also plays a critical role, with ‘BIG10’ firms commanding a premium, consistent with signalling theory, where clients associate larger firms with higher-quality assurance. However, client risk and corporate governance mechanisms appear to have little or no effect on audit fees; this shows that risk-based pricing (audit fee) models are still not adopted in the audit market in Kosovo, and governance practices remain underdeveloped as a determinant of audit fees.

Kosovo's regulatory reforms, particularly Law No. 06/L-032, have laid a foundation for standardised auditing practices by mandating IFRS and IFRS for SMEs compliance and licensing requirements. While our research does not directly quantify regulatory impacts, these changes likely contribute to the audit fee structures by elevating audit quality and accountability. The market also reflects nuanced dynamics: auditor tenure exhibits a moderate positive relationship with fees, potentially due to familiarity-driven premiums or incremental effort over time. Industry specialisation, though not significantly, hints at emerging demand for high expertise, signalling opportunities for firms to differentiate themselves.

Based on the research findings, audit firms should adopt transparent, client-tailored fee strategies that reflect the effort required for large or more complex audit engagements. Investing in specialised industry expertise might enhance competitiveness and justify a fee premium. Businesses, particularly MSMEs in Kosovo, are advised to negotiate fees proactively by leveraging insights into determinants like client size and complexity. Strengthening governance frameworks, while not directly linked to audit fees, may reduce audit workload and long-term audit fees. Policymakers must prioritise SMEs' accessibility through subsidies or simplified reporting standards and foster market competition to reduce overreliance on ‘BIG10’ licensed statutory audit firms. Regulatory bodies, such as KCFR for the case of Kosovo, should also develop risk-assessment guidelines to align Kosovo's practices with global best practices and international standards. Researchers are encouraged to investigate the longitudinal effects of regulatory reforms and conduct cross-country comparisons to distinguish between universal and context-specific determinants of audit fees.

The study relies on data from statutory licensed audit firms and audited entities in Kosovo. The availability and quality of these data may vary, potentially impacting the robustness of the findings. Some firms may not disclose all relevant information, leading to gaps in the dataset.

The implementation of Law No. 06/L-032 on Accounting, Financial Reporting, and Auditing in 2019 introduces a regulatory framework that could influence audit fees. However, as this law is relatively new, its long-term effects on audit fees might not be fully captured within the study period of our research.

The findings of this research are specific to the Kosovo audit market. While the study provides valuable insights, the results may not be directly applicable to other developing or transitional economies with different regulatory, economic, and market conditions.

Our dataset predates the full uptake of AI-enabled audits; subsequent studies should test whether digitalisation moderates size and complexity effects.

The research focuses on specific client and audit firm characteristics, but other factors such as economic conditions, industry-specific risks, and technological advancements in the auditing sector are not explored in depth in this research. These additional variables could also play a significant role in determining audit fees in the Kosovo audit market.

The process of determining audit fees involves a degree of professional judgment and negotiation between auditors and clients. This subjectivity can also introduce variability that is difficult to quantify empirically and control within the research framework.

Although this study has numerous limitations, it has provided an avenue for a more in-depth understanding of audit fee determinants within Kosovo's evolving market. As such, it has practical implications for businesses, regulators, and scholars. The findings invite more discussions in auditing and reporting, particularly within transitional economies digging their way through institutional and regulatory waters. This study, which grounds its findings on Kosovo's context, not only enriches local discussions but also creates an opportunity for dialogue beyond borders on balancing global standards to regional realities-one such conversation that is important for creating a level playing field and a resilient audit ecosystem around the world.