Conflicts are an inherent aspect of human interaction, arising across various contexts, including familial, social, and especially professional. The manner in which individuals respond to these conflictual situations it is a determining factor in their resolution.

In the military context, leaders frequently operate in environments characterized by a high degree of uncertainty and ambiguity, requiring them to make critical decisions rapidly and under pressure. These extreme conditions can generate elevated stress levels, thereby fostering the emergence of conflicts. Leadership and conflict management are closely interconnected, as inadequate handling of tensions can lead to dysfunctional conflicts with a negative impact on organizational effectiveness. In an environment founded on discipline and cooperation, unresolved conflicts can undermine the morale and performance of military personnel, diminishing both the tactical leader's ability to adapt to the complex demands of the modern battlefield and the unit's capacity to accomplish assigned missions and achieve the desired end state. Furthermore, the ability of tactical leaders to manage such situations not only strengthens interpersonal relationships within the unit but also contributes to maintaining organizational stability and preventing the escalation of tensions.

Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of how these leaders respond to various conflict situations specific to the military environment is essential for enhancing operational performance and ensuring a coherent and efficient organizational climate.

Although the concept of conflict has been extensively explored over time, with numerous definitions attributed to it, one of the most relevant remains the definition provided by Coser (1956). According to his perspective, conflict is defined as “a struggle over values and claims to scarce status, power and resources in which the aims of the opponents are to neutralize, injure or eliminate their rivals”. This view highlights the complex and competitive nature of conflicts, emphasizing both their structural and relational dimensions. Furthermore, this definition underscores that, beyond simple interpersonal tensions, conflict often involves social and structural dimensions, reflecting struggles for access to resources or positions of power. In this context, conflict can be interpreted as a mechanism through which social dynamics manifest, contributing both to change and the reinforcement of existing structures.

Regarding the clarification of the concepts of military leader and leadership, the situation is relatively straightforward, as their definitions have remained largely unchanged over time, though they may be adapted depending on the doctrine of each nation. In this study, military leader is associated with the tactical leader and defined as “anyone who by virtue of assumed role or assigned responsibility inspires and influences people by providing purpose, direction, and motivation to accomplish the mission and improve the organization” (ADP 6-22, 2019, pp. 1–3). Moreover, the concept of leadership is defined as “the activity of influencing people by providing purpose, direction, and motivation to accomplish the mission and improve the organization” (ADP 6-22, 2019, pp. 1–3).

Conflicts within organizations stem from a combination of internal and external factors that reflect the complexity of interpersonal and structural dynamics. Internally, conflicts may arise from divergences in values, ineffective communication, emotional tensions, or role ambiguity, when individuals lack clarity regarding their responsibilities or perceive inconsistencies in role expectations (Rusu, 2016). Externally, factors such as competition for limited resources and rigid hierarchical structures can intensify tensions (Isa, 2015). Poor communication is particularly detrimental, as it fosters misunderstandings, erodes trust, and impairs overall productivity. Additionally, task interdependence, where individuals or units rely on each other to complete assignments, can exacerbate friction if not properly managed (Kiitam, McLay & Pilli, 2016). Diverging goals among individuals or departments, even in the presence of a shared organizational mission, may also result in conflict.

To better understand and address these conflicts, researchers have developed various typologies that classify them by nature, level, and impact. One of the most influential frameworks is proposed by Deutsch (1973), who distinguishes between six types of conflict (vertical, contingent, displaced, misattributed, latent and false conflicts) based on the interaction between objective realities and subjective perceptions. Toncheva-Zlatkova (2023) offers a more structural approach, classifying conflicts according to the level at which they occur, ranging from intrapersonal to intergroup and their consequences, whether constructive or destructive. This typology is further extended by Hussein and Salem (2019), who introduce intra- and interorganizational conflicts. Additional distinctions are made between interest-based, cognitive, and organizational conflicts, as well as between task-related and relational conflicts (Dahir, Cetinkaya & Rashid, 2019). These analytical models contribute significantly to the understanding of how conflict manifests and evolves within complex organizational environments.

Within an organization, conflicts can produce both positive and negative effects. Numerous studies highlight both the issues that arise when conflicts are mismanaged or ignored and the opportunities that emerge from their proper management.

One study conducted by Parashar and Sharma (2020) emphasizes the idea that the continuous ignoring of conflicts can lead to the worsening of the situation and a decrease in productivity, both for the involved parties and for the organization as a whole. Moreover, according to the authors, other effects that may arise include damage to the organization's reputation, increased stress levels, low motivation among members, and a higher turnover rate.

In line with the ideas stated above, Wogwu, Vinazor and Wali-Innocent (2024) emphasize that unresolved conflicts hinder the achievement of both personal and organizational goals. They identify negative consequences such as slowed work pace, reduced cooperation, lower organizational commitment, and inappropriate behaviors. However, they argue that effective conflict management can strengthen relationships, enhance cohesion, and foster a harmonious work environment that encourages cooperation.

A final article highlights both the positive and negative aspects of conflicts in organizations. On the positive side, conflicts can foster creativity and improve interpersonal management, while negatively, they may cause resistance to change, distrust, and hinder development. Poorly managed conflicts can escalate, disrupting the organization's mission, causing delays, disengagement, and even chaos. Conversely, effectively managed conflicts promote problem-solving, innovation, and creativity, benefiting both the organization and its members (Igbokwe, 2024).

In the academic literature, conflicts are analyzed from multiple perspectives and categorized into distinct groups based on their nature and the factors involved.

Pondy's model (1967) is one of the most influential theoretical models of organizational conflict. In his work, the author treats conflict as a dynamic process composed of a series of distinct episodes, each with its own characteristics and stages. His model focuses on identifying and understanding these stages to better analyze conflict within organizations. The five stages of Pondy's model are: latent conflict, perceived conflict, felt conflict, manifest conflict, conflict aftermath. In a positive manner, Mostafa and Yiu (2012) highlight that Pondy's model emphasizes the importance of understanding the conflict process and its impact on the quality of relationships within the organization. However, other studies point out that while Pondy's model successfully distinguishes latent tensions from the perception of conflict and subsequent actions, it presents vague stages and focuses on the role of perception, suggesting that a conflict must be perceived before being felt, and felt before being acted upon (Easterbrook et al., 1993).

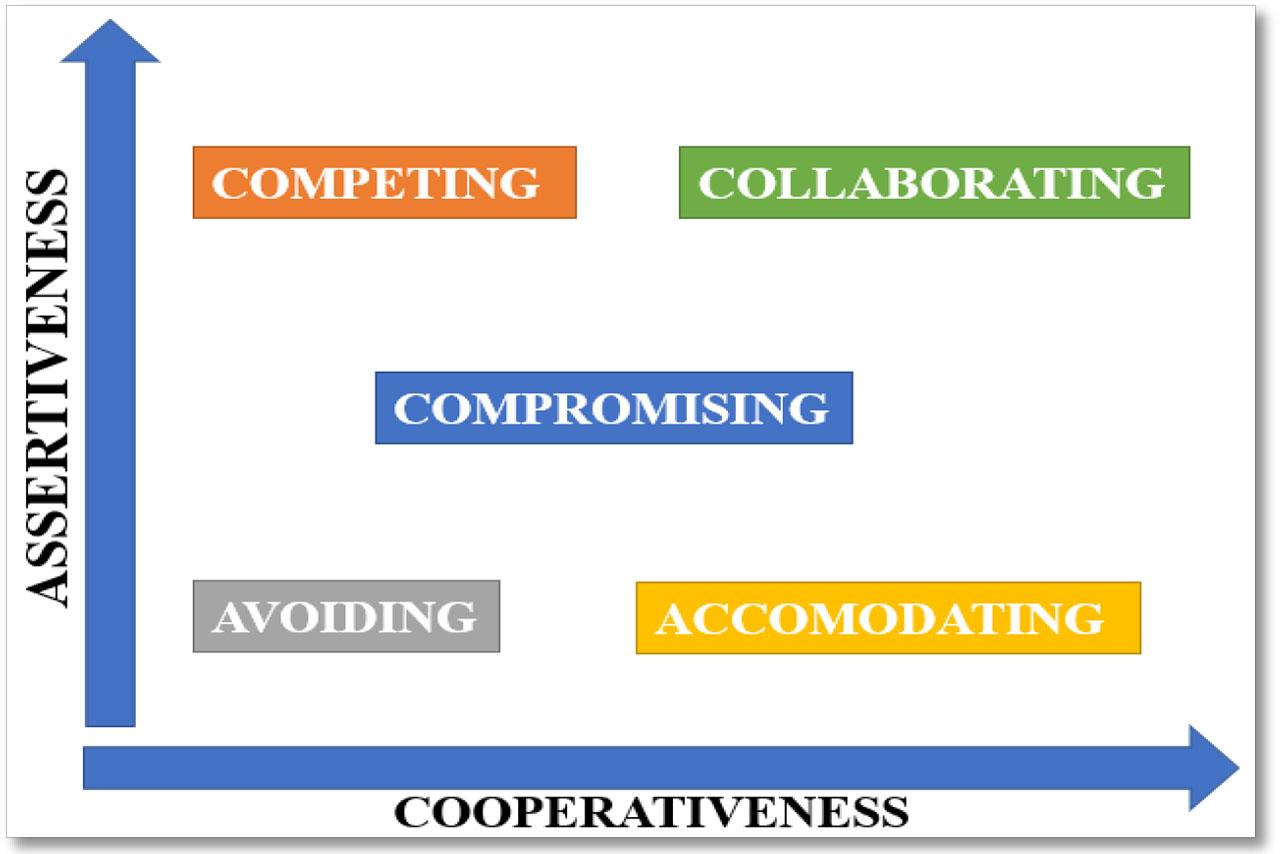

The Thomas-Kilmann (TK) conflict resolution model examines how individuals respond to conflict situations. In such situations, a person's behavior can be described based on two fundamental dimensions. The first dimension refers to assertiveness, which is the degree to which an individual attempts to satisfy their own interests. The second dimension refers to cooperation, which is the degree to which an individual attempts to satisfy the interests of the other party. These two behavioral dimensions are used to define five conflict management styles: avoiding, accommodating, compromising, competing, and collaborating (Thomas & Kilmann, 1976).

The validity of the instrument has been confirmed through multiple empirical studies, demonstrating that it consistently measures the conflict management styles proposed by the authors. For example, the study conducted by Ben-Yoav and Pruitt (1984) supported both its convergent validity and temporal stability, particularly in organizational settings. In addition, Holt and DeVore (2005) demonstrated the international applicability and relevance of the TK instrument by successfully using it in cross-cultural contexts. More recently, the study by Temmar and Tadjine (2024) reconfirmed the factorial structure of the instrument, adapted to a Likert scale, on an organizational sample, further reinforcing the theoretical consistency of the five conflict management styles.

Having clarified the main theoretical issues, the aim of the study is to identify how tactical leaders in the Romanian Land Forces (RLF) respond to conflict situations, the main causes of conflicts and their consequences within the military organization.

The research objectives (RObj) were formulated in accordance with the defined study purpose as follows:

- ➢

RObj1 – determining the predominant response style to conflict situations according to the opinions of RLF tactical leaders;

- ➢

RObj2 – examining whether there are statistically significant differences in the conflict response styles adopted by tactical leaders within RLF based on independent variables such as operational experience, gender, branch, or staff category;

- ➢

RObj3 – identifying the main three conflict-generating causes in the military organization based on the perspectives of tactical leaders within RLF;

- ➢

RObj4 – establishing the potential effects of conflicts within the military organization as perceived by the tactical leaders.

Furthermore, the following research hypotheses (RH) were formulated to address the research objectives:

- ➢

RH1 – the collaborating style is the predominant response to conflict situations, according to the opinions of RLF tactical leaders;

- ➢

RH2 – there are statistically significant differences in the conflict response styles adopted by tactical leaders within RLF depending on independent variables such as operational experience, gender, branch, or staff category;

- ➢

RH3 – the main three conflict-generating causes within the RLF, as identified by the tactical leaders, are work-related task interdependence, poor communication between organization members, and limited resources sought by multiple entities;

- ➢

RH4 – According to RLF tactical leaders, the majority of conflicts within the military organization have negative outcomes.

This paper primarily relies on a quantitative approach, employing an indirect survey based on a questionnaire, in conjunction with qualitative methods such as a comprehensive literature review and indirect observation.

The questionnaire, consisting of 34 questions, is directly aligned with the theoretical aspects discussed in the literature review. The first 30 questions address RObj1 (RH1) and Robj2 (RH2) and are divided into five sets of six questions each. In addition, each set corresponds to a conflict response style according to the Thomas-Kilmann model as follows: set A – avoiding style, set B – competing style, set C – collaborating style, set D – accommodating style, set E – compromising style. Moreover, responses were rated using a five-point Likert scale, as follows: 1 – strongly disagree; 2 – disagree; 3 – neither agree nor disagree; 4 – agree; 5 – strongly agree.

Question 31 addresses RObj3 (RH3), aiming to identify the main causes that may lead to the emergence of conflicts within the military organization. The respondents were provided with the opportunity to select one cause from those delineated in the theoretical section of the study. Finally, the final three questions were directed at RObj4 (RH4). Initially, respondents were asked to determine whether conflicts within the military organization generally have negative or positive consequences. Based on their answer, tactical leaders were then asked to identify the most prevalent positive/negative effect resulting from conflicts experienced in the work environment.

The study was conducted on a sample of 100 commissioned officers, non-commissioned officers (NCOs) and enlisted soldiers from the Romanian Land Forces (RLF), which due to the functions and responsibilities they fulfill, can be considered tactical leaders. Additionally, the questionnaire was distributed to both male and female personnel and was self-administered. Respondents were provided with explanations regarding the topic's relevance and guidance on how to complete the questionnaire. The process was anonymous, on a voluntary basis, and required approximately 10–15 minutes to fill out.

In terms of the sample's distribution by staff category, 34 participants were commissioned officers, 33 NCOs, and 33 enlisted soldiers. From the perspective of gender distribution, the sample consisted of 80 male military personnel and 20 female military personnel.

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS) software, version 30, provided the foundation for the data processing necessary to test the validity of the hypotheses and to achieve the stated objectives. The statistical data processing began with a descriptive analysis of the variable R (the variable composed of the 30 items corresponding to the five response styles to conflict situations). This analysis yielded the following results: Mean = 3.71 and Standard Deviation = 0.4. By subtracting/adding the standard deviation from/to the mean, the lower/upper limits of typical variation were determined (Lower limit = 3.31 / Upper limit = 4.11). Analyzing the average scores of the five response styles to conflict situations and comparing them to the Z distribution, it can be observed that no style falls outside the typical variation limits. Furthermore, by comparing the scores of the 30 items to the Z distribution, the items that fell outside the typical variation limits were identified.

Moreover, to assess the internal consistency of the questionnaire within the current research context, Cronbach's Alpha coefficients were calculated for each of the five subscales. The results indicate acceptable to good reliability levels: 0.731 for set A, 0.698 for set B, 0.704 for set C, 0.711 for set D, and 0.777 for set E. These values confirm the internal consistency of the instrument when applied to the sample used in this study and support its suitability for measuring conflict management styles in the military organizational context.

Statistical analysis of response styles to conflict situations calculated for the entire research sample

Within Set A of items referring to the avoiding style, item A1 (There are times when I let others take responsibility for resolving the conflict) received the lowest score (2.93). This indicates a low tendency to avoid conflict situations, which may reflect a certain level of personal responsibility or an attitude that avoids passing conflicts on to others. Additionally, this behavior may be influenced by strong norms within the military organization that encourage individual accountability, even indirectly. Conversely, item A2 (I do everything I can to avoid unnecessary tensions) received the highest score (4.26). This score suggests that respondents exhibit a significant concern for reducing unnecessary tensions and fostering a harmonious organizational climate. However, a high score may also indicate an aversion to conflicts in general, which could lead to neglecting issues that require active resolution.

Within Set B of items referring to the competing style, items B3 (I push to impose my point of view in workplace disputes) and B6 (I try to convince the other party of the advantages of my position) received scores below the lower limit of typical variation (B3=2.65, B6=3.24). At the opposite pole, item B1 (I am usually firm in defending my point of view) obtained a significantly higher score (4.24) than the upper limit of typical variation. The interpretation shows that tactical leaders associate firmness with acceptable competitive behavior but avoid aggressive or manipulative tactics like persistent persuasion. Overall, respondents favor a balanced competing style, combining assertiveness with respect for others to prevent unnecessary tension. This approach reflects an adaptive conflict management style that blends competitive and collaborative elements based on context.

Within Set C of items referring to the collaborating style, item C6 (I try to resolve differences of opinion immediately) received the lowest score (3.47), while item C2 (I always want to discuss directly the issue I have with the other party) received the highest score (4.30). By comparison, the differences between these two items suggest a preference for a collaborating style that favors direct communication but does not insist on the immediate resolution of conflicts. Respondents seem more concerned with the quality of dialogue rather than the speed of conflict management, likely preferring to take the time needed to negotiate optimal solutions.

Within Set D of items referring to the accommodating style, item D3 (Sometimes I sacrifice my own desires so that the other person can satisfy theirs) received a relatively low score (3.21). At the opposite extreme, item D6 (When negotiating conflict resolution, I try to respect the other person's wishes) received the highest score (4.00). The difference between these two scores suggests that, despite a reluctance toward constant self-sacrifice, respondents are still open to respecting others' viewpoints in the negotiation process.

Within Set E of items referring to the compromising style, item E2 (I give up certain viewpoints in favor of others) received the lowest score (3.22), while item E5 (I propose a middle ground to resolve potential workplace conflicts) received the highest score (4.01).

The results suggest that tactical leaders are equipped to negotiate and collaborate while balancing firmness with adaptability. This ability allows them to defend their perspectives confidently while remaining open to compromise when necessary. Such an approach is essential in a military context, where teamwork, flexibility, and clear decision-making are crucial for operational success. By maintaining this balance, military personnel can foster cooperation across individuals and units, ensuring both discipline and cohesion. Their willingness to adapt without compromising core principles contributes to efficient conflict resolution and mission success, reinforcing both individual leadership skills and collective effectiveness.

Thus, considering the previously presented information, it can be concluded that the predominant conflict resolution style among tactical leaders within RLF is the collaborating style, which received the highest score (3.90). This is followed by the compromising style (score 3.67), the competing and accommodating styles (identical scores of 3.66), and finally, the avoiding style (score 3.65).

In order to test the validity of the formulated hypothesis, data were collected from as wide a variety of military personnel as possible, both in terms of operational experience and from the perspective of gender, staff category, or military branch.

As can be seen in Figure no. 2, the sample's average experience was approximately 7 years. In addition, the most frequently reported value was 1 year (33 tactical leaders), followed by 2 and 3 years (12 tactical leaders each), and 15 years (9 tactical leaders). Based on the mean value, the sample was subsequently divided into two categories: a group of more experienced personnel (with 8 or more years of service), comprising 37 military personnel, and a group of less experienced personnel (with 7 years or less), comprising 63 military personnel.

Thomas-Kilmann conflict model

(Source: Author' own research)

The graphic representation of the sample's operational experience

(Source: Authors' own research – generated by IBM SPSS, version 30)

To assess whether statistically significant differences exist in the conflict response styles of tactical leaders within the RLF, based on variables such as operational experience, military branch, gender, and staff category, several independent samples T-tests were applied.

The first independent samples T-test was conducted to examine whether differences in operational experience among military personnel are associated with variations in conflict response styles. The results of the analysis revealed the following:

- ➢

there are significant differences in conflict response styles based on the level of operational experience, suggesting that tactical leaders with varying experience tend to approach conflict differently (t = 1.682, df = 53.342, p = 0.038);

- ➢

experienced tactical leaders reported significantly greater use of the compromising style (m1 = 3.76) compared to their less experienced counterparts (m2 = 3.62), (t = 1.138, df = 59.728, p = 0.026);

- ➢

similarly, the accommodating style is more frequently employed by experienced leaders (m1 = 3.79) than by less experienced ones (m2 = 3.58), (t = 1.882, df = 98, p = 0.041);

- ➢

no significant differences were found in terms of the avoiding style (t = 1.219, df = 59.429, p = 0.228), the competing style (t = 1.669, df = 98, p = 0.098), and the collaborating style (t = 1.335, df = 98, p = 0.185).

The results demonstrate that more experienced tactical leaders have had more time to learn and apply effective conflict management strategies. As the time spent in the military environment increases, individuals are exposed to a greater variety of conflict situations, which makes them adopt more balanced and adaptive styles. These styles are essential in the military environment, where collaboration and functional relationships are crucial for mission success.

From another perspective, the clear hierarchy characteristic of the military environment may often promote the adoption of an avoiding style by soldiers with lower ranks and a competing style for soldiers with higher ranks. However, in this research, the differences were not statistically significant, which highlights the idea that in the military, soldiers are aware that success depends on the degree of collaboration, developing a tendency to manage conflicts in a way that minimizes tensions and ensures the cohesion of the unit.

To further investigate whether significant statistical differences exist in the conflict response styles adopted by tactical leaders from combat and combat support branches, the sample was divided into two main categories: combat branches (Infantry, Reconnaissance, Paratroopers, Mountain Troops) and combat support branches (Artillery, Military Police, Electronic Warfare, CBRN, Communications). A T-test for independent samples was applied to compare the two groups. The results revealed statistically significant differences in the preferred styles of conflict resolution (t = 2.020, df = 52.418, p = 0.048), suggesting that the operational demands specific to combat branches may shape a more assertive approach to conflict. Tactical leaders from combat branches, who frequently operate in high-pressure environments requiring rapid decision-making and strict hierarchical coordination, tended to report a higher preference for assertive styles such as competing and collaborating. In contrast, leaders from combat support branches, typically engaged in technical, logistical, or regulatory tasks, appeared more inclined toward accommodating or avoiding styles. These findings reinforce the notion that branch-specific operational contexts influence the development of preferred conflict management strategies, supporting the revised objective and hypothesis.

Finally, the application of the T-test, using gender as an independent variable, did not identify statistically significant differences regarding how soldiers choose their response style to conflict situations (t = 1.104, df = 98, p = 0.272). Additionally, it was observed that the staff category does not influence the individual's response to conflict situations.

To achieve the third research objective, the data will be extracted from the responses of the research sample to item 31, which can be analyzed in Table no. 2.

Main causes generating conflicts within RLF according to the opinion of the surveyed sample

| Identified Cause | Frequency of Responses |

|---|---|

| poor communication between organization members | 43 |

| hierarchical structure and abuse of power | 18 |

| contradictory interests and objectives | 14 |

| limited resources sought by multiple entities | 9 |

| conflicting values and principles | 7 |

| interdependence of work-related activities | 6 |

| role ambiguity | 3 |

Thus, the three main causes identified by the research sample that can lead to conflicts in the military organization are: poor communication between members of the organization, the hierarchical structure and abuse of power, and contradictory interests and objectives.

Poor communication in the military can stem from unclear information, lack of feedback, or rigid formalities, leading to misunderstandings that strain trust and efficiency. Strict hierarchical channels may also create frustrations by limiting transparency and open dialogue. Therefore, poor communication is considered the main cause of conflict in the military organization. Additionally, excessive or abusive authority within the chain of command can cause conflicts, as superiors imposing decisions without considering subordinates' needs may generate frustration and resistance. Perceived injustice or lack of transparency further impacts morale. Furthermore, conflicts also arise from competing objectives, such as career ambitions or resource allocation. Unmanaged expectations can lead to rivalries, especially during organizational changes that some perceive as disadvantageous.

As statistics show, it was found that 74% of the analyzed sample believes that conflicts that arose in the military organization had negative effects within the organization. The main negative effects identified were a decrease in the level of cooperation between the members of the organization, as well as an increase in stress levels. The surveyed tactical leaders identify decreased cooperation as a key negative effect of conflicts in military organizations, as mission success relies on coordination, trust, and collaboration. Tensions and misunderstandings hinder communication, weaken interpersonal relationships, and reduce group cohesion, impairing teamwork. Additionally, increased stress levels negatively impact both individual performance and overall well-being, leading to demotivation, frustration, and lower unit morale, ultimately reducing operational effectiveness in critical situations.

In a completely opposite manner, 26% of the analyzed sample considered conflicts as catalysts that produce positive effects within the military organization. Thus, the main positive effect mentioned by the surveyed sample was the improvement of the level of collaboration and cooperation among the members of the targeted structures. While conflicts are often seen as negative, effective leadership can reveal underlying issues, clarify misunderstandings, and improve relationships. Differing opinions may foster innovation and align objectives. In the military, addressing conflicts openly promotes learning, adaptation, and stronger cohesion. Table no. 3 highlights additional negative and positive effects identified by the surveyed sample.

The main negative/positive effects of conflicts within RLF

| Identified Effect | Frequency of Responses | |

|---|---|---|

| Negative effects | increased stress levels | 20 |

| reduced cooperation | 20 | |

| decreased motivation | 17 | |

| decreased productivity | 13 | |

| escalation of conflict | 4 | |

| Positive effects | improving collaboration and cooperation | 16 |

| enhancing performance | 4 | |

| stimulating creativity and innovation | 3 | |

| improving cohesion | 3 | |

At the end of the study, it can be affirmed that all research objectives have been successfully met. Concerning the proposed hypotheses, data interpretation leads to the following conclusions:

- ➢

RH1 was invalidated, as the results suggest a composite response pattern, in which tactical leaders within the RLF tend to adopt a flexible approach that incorporates multiple conflict management behaviors, depending on the context;

- ➢

RH2 has been partially validated, as statistically significant differences were observed only regarding certain independent variables, such as operational experience and branch, but not gender or staff category;

- ➢

RH3 was partially invalidated, as the three main causes identified by the research sample that can lead to conflicts in the military organization are: poor communication between members of the organization, the hierarchical structure and abuse of power, contradictory interests and objectives;

- ➢

RH4 has been validated, as tactical leaders within the RLF believe that conflicts have generally negative effects in the organization.

In conclusion, this study highlights the importance of effectively managing conflicts in an environment characterized by discipline, strict hierarchy, and cooperation. The results emphasize that how individuals react to conflicts is influenced by professional experience as well as the specifics of the military organization, where mission success depends on clear communication and the ability to maintain team cohesion. Furthermore, the predominant perception of conflicts is negative, with them being associated with decreased cooperation and increased stress. However, there is also a perspective suggesting that disputes can contribute to improved collaboration and the identification of constructive solutions.

To sum up, I believe these findings underline the need for future research aimed to develop effective conflict management strategies within the RLF, through the promotion of a climate based on open communication, mediation, and fair dispute resolution.