Palliative medicine is directed toward providing comprehensive, multidimensional support to patients with incurable diseases for whom causal therapy is no longer an option. By definition, palliative care encompasses medical, social, and spiritual interventions aimed not only at alleviating patient suffering but also at supporting the family confronted with a life-threatening illness. In recent years, both in Poland and internationally, there has been a marked and continuous increase in the demand for palliative care services. [1, 2, 3]. Public awareness of the need for palliative and hospice care has traditionally focused particularly on patients with cancer, in line with the founding principles of the first hospices. However, according to current recommendations, advanced life-threatening conditions resulting from non-oncological diseases, similarly to cancer, should also be managed within palliative care settings, including hospices [1, 4].

Radbruch et al. (2020) proposed a new consensus-based definition of palliative care: Palliative care is the active, holistic care of individuals of all ages who experience serious health-related suffering due to severe illness, particularly those near the end of life. It aims to improve the quality of life of patients, their families, and their caregivers [5].

In the Polish context, the legal framework governing the organization and provision of palliative and hospice medical services is established by the Regulation of the Minister of Health of 29 October 2013. This regulation specifies a precise list of medical conditions whose diagnosis qualifies patients for palliative care. While the list of oncological diseases is extensive, non-oncological conditions are significantly fewer, including respiratory failure, cardiomyopathy, pressure ulcers, and selected demyelinating diseases of the nervous system [6]. One of the forms of providing palliative care services in Poland is inpatient hospice care.

Polish law does not provide explicit regulations regarding the resuscitation of patients at the end of life. Physicians make decisions based on three legal instruments: the Code of Medical Ethics, the Act on the Professions of Physician and Dentist, and the Act on Patients’ Rights and the Patients’ Rights Ombudsman. According to the Code of Medical Ethics, a physician is obliged to make a resuscitation decision based on a thorough assessment of the patient’s condition, the course of previous treatment, and an analysis of available therapeutic options, while respecting the patient’s priorities. The decision should protect the patient from additional suffering and prevent interventions that are unjustified according to current medical knowledge [7].

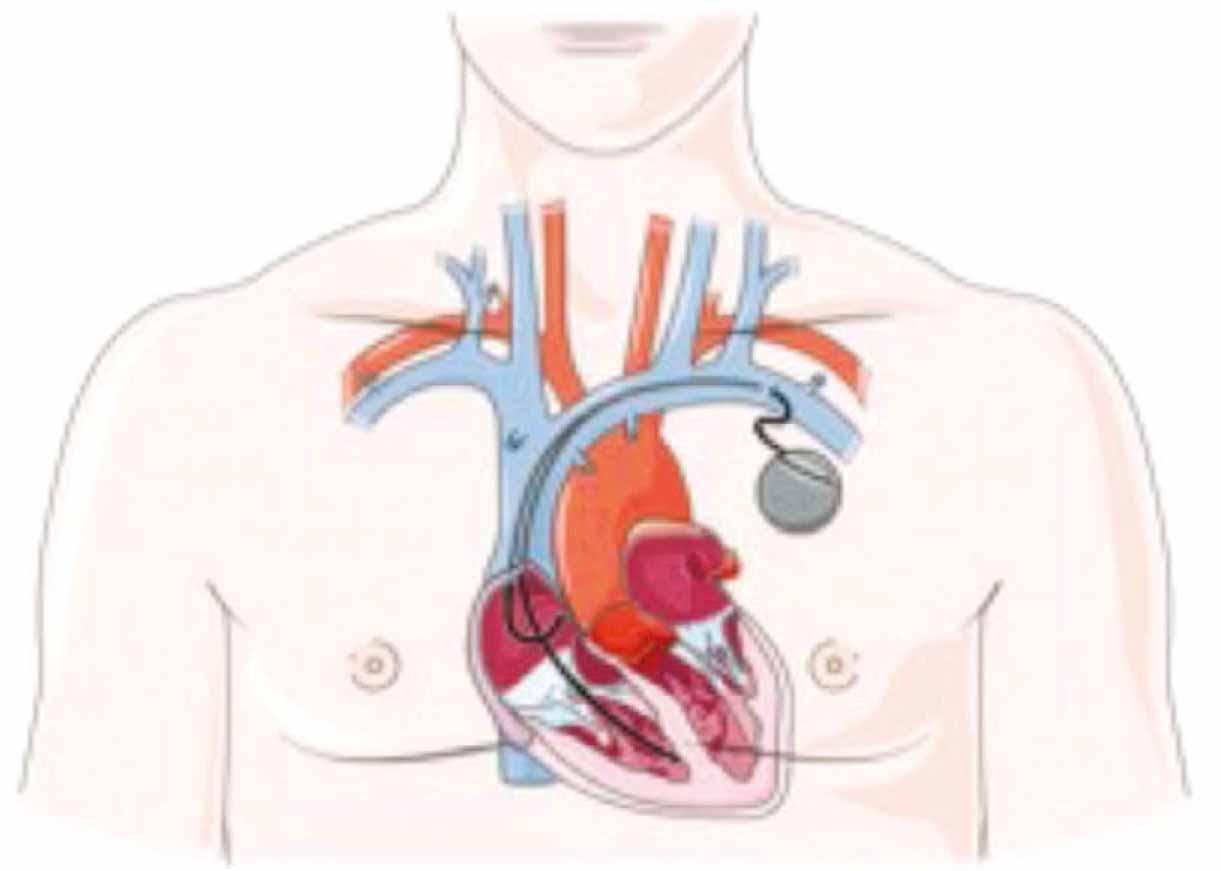

A 73 years old woman, a patient of a stationary hospice was admitted to the emergency department (ED) due to cardiac arrest with return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) after a successful attempt of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) by the hospice’s doctor. The patient is chronically bedridden and suffering from pressure sores, whose background include multiple sclerosis (MS), hypothyroidism and diabetes mellitus type 2. Upon admission, her respiratory tract was secured with a laryngeal tube and ECG scan indicated a third-degree atrioventricular (AV) block with heart rate (HR) of approximately 40/min, blood pressure (BP) 140/75. She was unconscious (Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) 4 - signs of a post-resuscitation brain injury in neurological examination, secured with an endocavitary electrode. At the ED, she was consulted by an anaesthesiologist and a cardiologist. Anaesthesiologist concluded that given the patient’s current clinical picture and past medical history, her prognosis was rather unfavourable and that escalation of therapy including instrumental techniques, if the brain damage is confirmed in the CT, would bear the hallmarks of futile therapy. CT scans without contrast enhancement of head, neck and chest were conducted. CT of the head showed no signs of acute intracranial bleeding, yet it demonstrated chronic vascular changes in the periventricular white matter of both cerebral hemispheres, subcortical atrophy, atherosclerotic plaques in the siphons of both internal carotid arteries (ICAs), calcified meningioma/osteoma adjacent to the inner table of the right parietal bone, measuring up to 9 mm in maximum dimension. CT of the chest showed no signs of pulmonary embolism, however ground-glass opacities in the upper lobes of both lungs were noted, likely with an edematous component, consolidations in the parenchyma of the right lower lobe of the lung and pleural effusion in both pleural cavities. Blood tests including biochemistry, haematology and inflammatory markers were gathered in Table 1 and administered medications throughout the patient’s stay at the hospital in Table 2. Later on, given lack of cerebral damage confirmed in the CT, the patient was transferred to a cardiological ward, where she underwent implantation of a dual-chamber pacemaker (VitatronG70A2 s/n 550262566G device device) (Figure 1). During the procedure, antibiotic prophylaxis was commenced (Cefazolin 2g,) (Table 2). After the implantation procedure her status improved and was consulted by a neurologist and a surgeon (due to her chronic pressure sore). Physical examination revealed spastic paresis of the left upper and lower limbs and right lower limbs, MRC grade 2 and superficial pressure ulcer in the sacral area, without skin necrosis. Considering her comorbidities and immobility, venous thromboembolism prophylaxis was started (Enoxaparin), insulin therapy and regular medications were prescribed (Table 2). The decision was made to transfer the patient to a neurological ward to undergo further treatment. During her stay, she was consulted by an internist upon delivery of her Hospital Discharge Summary from previous hospitalisation, which indicated primary hypothyroidism. Patient was reviewed by general medicine specialist, who commenced treatment of primary hypothyroidism (with Levothyroxine). After a 6-day stay, during which her condition improved, she was transferred to a neurological rehabilitation ward due to her immobility with spastic paresis of the left upper (Lovett scale III) and lower limbs, and right lower limbs (Lovett scale II), MRS 5. Additionally, the attending physician issued a referral to a long-term care facility. On the rehabilitation ward, the patient underwent both physio- and psychotherapy. The assessment of the psychotherapist revealed that the patient has limited mobility within the bed, requires significant assistance with turning, and passive transfer to a sitting position. In the seated position, she is unstable and requires external stabilization. Transfer to a wheelchair requires assistance. Sitting tolerance: stimulation duration approximately 15 minutes, total time spent sitting 2 hours. Paresis affecting three limbs: Left upper limb – paresis more pronounced in the distal joints, with limited movement in the proximal joints. Left lower limb – paresis pronounced throughout the limb, with palpable increased muscle tone in all joints. Right lower limb – active movements present but with limited range of motion. Neuropsychological assessment showed that the patient was verbally and logically coherent, and orientated as to time, space and self. Neuropsychological assessments revealed persistent deficits related to attention function (sustained attention), as well as executive functions (planning). Mood was mildly depressed, affect was congruent with mood. Psychomotor drive was slowed. As a result of the implemented rehabilitation, mild improvement was achieved. The patient, in a stable condition with persistent three-limb paresis, bedridden and assisted into a wheelchair, was transferred to a nursing home.

A dual-chamber pacemaker woth ventricular lead implanted close to right

Selected laboratory findings trought patirnt’s hospitalisation

| Emergency department (No. of days: 1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Test | Result | Range | |

| BUN | 11.6 mg/dl | 9.0-22.0 | |

| CRP | 3.0 | 0.00-5.00 | |

| NT-pro BNP | 4069.0 pg/ml H | <125 | |

| Troponin T | 47.4 ng/l H | <14.0 | |

| Cardiological ward (No. of days 21) | |||

| BUN | Day 2 | 12.1 mg/dl | 9.0-22.0 |

| CRP | Day 2 | 36.8 mg/l H | 0.00-5.00 |

| Creatinine | Day 2 | 0.59 mg/dl | 0.40-1.20 |

| Nt-pro BNP | Day 3 | 12155.0 pg/ml H | <125 |

| PCR | Day 2 | 0.42 ng/ml | <0.5 ng/ml - low risk of sepsis |

| Neurological ward (No. days 6) | |||

| BUN | Day 2 | 13.1 mg/dl | 9.0-22.0 |

| CRP | Day 2 | 96.3 mg/l H | 0.00-5.00 |

| Creatinine | Day 2 | 0.60 mg/dl | 0.40-1.20 |

| Neurological rehabilitation ward (No. days 29) | |||

| BUN | Day 2 | 11.3 mg/dl | 9.0-22.0 |

| CRP | Day 2 | 45.9 mg/dl H | 0.00-5.00 |

| Creatinine | Day 2 | 0.55 mg/dl | 0.40-1.20 |

| BUN-Blood urea nitrogen, CRP-C-reactive protein, PCR - Procalcitonin | |||

Medications administered during patient’s stay

| Ward | Medications |

|---|---|

| ED | Isotonic solution i.v. 500 ml |

| Cardiological ward | Cefazolin i.v. 1g, Enoxaparin s.c. 80mg/0.8ml, Glucose 5% i.v. 50 mg/ml, Hydroxyzine in tab. 25 mg, Insulinum humanum s.c. 100 U/I, Insulinum humanum isophanum s.c. 100 U/I, IPP in Tab. 20 mg, Ketoprofen i.v. 50 mg/ml, Lidocaine 1% i.v., Lorazepam in tab. 1 mg, Zolpidem tartrate in tab. 10 mg, Hialuronic isotonic inhalation solution, Iohexol i.v. 647 mg/ml (0.3 g of iodine), Non-adhesive foam dressing with Hydrofiber® technology and silver on sacrum, Isotonic solution i.v. 500ml, Paracetamol i.v. 10 mg/ml, Paracetamol in tab. 500 mg, Ramipril in tab. 5 mg, Pantoprazole i.v. 40 mg, Paracetamol and Tramadol in tab. 37.5 mg +325 mg, Torasemide in tab. 10 mg, Torasemide in tab. 5 mg, Torasemide i.v. 5mg/ml |

| Neurological ward | Ceftriaxone i.v. 2g, Enoxaparin s.c. 40 mg, Estazolam TZF in Tab. 2 mg, Insulinum humanum s.c. 100 U/I, Insulinum humanum isophanum s.c. 100 U/I, IPP in tab. 20 mg, Lactobacillus in caps., Levothyroxine sodium in tab. 100 mcg, Non-adhesive foam dressing with Hydrofiber® technology, Adhesive foam dressing with silicone contact layer, Hydrophilic polymer foam dressing, Torasemide in tab. 5 mg |

| Neurological rehabilitation ward | Ceftriaxone i.v. 2g, Enoxaparin s.c. 40 mg, Furazidin in tab. 20 mg, IPP in tab. 20 mg, Potassium in tab. 391 mg K+, Lactobacillus., Levothyroxine sodium in tab. 50 mg, Natrium chloratum 0.9% i.v., 100 ml, Insulin aspart+- Insulin aspart protamine suspension s.c. 100 U/I, Torasemide in tab. 5 mg |

| caps. – capsules; ED - Emergency Department; g – gram; i.m. – intramuscular; i.v. – intravenous; IPP – proton pump inhibitor; IU / JM – international units; mcg – microgram; mg – milligram; ml – milliliter; s.c. – subcutaneous; tab. – tablet; U/I – units of insulin. | |

Palliative and palliative care represent an integral component of the healthcare system, designed for patients with incurable, progressive, and life-limiting conditions no longer amenable to disease-directed treatment. The principal objective is the optimization of quality of life through effective control of pain and other distressing symptoms, alongside the mitigation of psychological, social, and spiritual suffering. Care also encompasses structured support for families, who frequently face considerable emotional and social challenges [8].

In Poland, these services are publicly funded by the National Health Fund and are delivered across several modalities. Inpatient care, provided in hospital-based palliative medicine wards and hospices, is dedicated to patients with advanced disease and refractory symptoms and may include short-term respite admissions. Outpatient care is available through specialized palliative medicine clinics, whereas home-based care enables patients to remain in familiar surroundings, supported by physicians, nurses, psychologists, physiotherapists, and 24/7 medical consultation [9].

Eligibility for palliative and hospice services is based on medical criteria and includes both oncological and non-oncological diseases, such as advanced cancer, AIDS, neurological sequelae, selected forms of respiratory and cardiac failure, and chronic non-healing wounds including pressure ulcers. Multidisciplinary teams provide comprehensive, holistic care that integrates medical treatment with psychosocial and rehabilitative interventions. Patients are entitled to diagnostic services, essential medications, and medical devices free of charge. Admission requires referral from a licensed physician, with final qualification determined by the attending specialist within a hospice or palliative care ward [1, 6].

Despite the patient’s severe general condition and multiple comorbidities, the patient did not meet the criteria warranting inpatient hospice care. According to established definitions, palliative and hospice care is intended for patients with advanced, progressive, and life-limiting conditions in which causal treatment is no longer effective, and the primary goal is symptom relief. In this case, despite chronic immobility, pressure ulcers, and spastic limb paresis, specialized interventions led to measurable improvements: successful implantation of a dual-chamber pacemaker, implementation of neurological and endocrine therapies, and initiation of rehabilitation, followed by transfer to a neurological rehabilitation unit and subsequently to a long-term care facility.

Although the patient required continuous assistance and rehabilitation, her condition did not correspond to end-stage disease with irreversible symptom progression, which constitutes the primary indication for inpatient hospice admission. She was hemodynamically stable, verbally and cognitively coherent, and able to participate in physiotherapy and psychotherapy. The interventions implemented allowed for ongoing functional maintenance outside of a hospice setting. Therefore, referral to a long-term care facility and continuation of rehabilitation was the most appropriate course of action, rather than continued inpatient hospice care.

This case highlights the complexity of decision-making in palliative and hospice care, particularly when patients present with acute, potentially reversible conditions despite advanced chronic comorbidities. The successful resuscitation and subsequent medical interventions, including pacemaker implantation, neurological and endocrine treatment, and rehabilitation, led to a significant improvement in the patient’s overall condition. As a result, she no longer met the criteria for inpatient hospice admission, which is reserved for patients with irreversible symptom progression and end-stage disease. Instead, long-term care with continued rehabilitation proved to be the most appropriate solution, ensuring the patient’s medical stability and preserving her functional and cognitive abilities. This case emphasizes the importance of holistic assessment in hospice and palliative care, as well as the need for flexible care pathways that adapt to changes in a patient’s prognosis and clinical status.