Toxoplasmosis is one of the most common zoonotic diseases worldwide, caused by the protozoan Toxoplasma gondii. This parasite can infect various mammalian species, including humans, making it a significant concern in medicine and public health [1,2]. It is estimated that 30% to 50% of the global population has been exposed to this pathogen. Most infections are asymptomatic. However, in certain individuals, particularly those with weakened immune systems, pregnant women, and newborns, serious health complications may arise [3,4].

One of the most severe complications of toxoplasmosis is ocular toxoplasmosis. This condition is the leading cause of retinochoroiditis worldwide [4]. It can result in significant visual impairment and, in extreme cases, complete blindness [4,5]. Importantly, ocular toxoplasmosis occurs in individuals with both congenital toxoplasmosis and those with acquired infections. The most common symptoms include decreased vision, floaters, photophobia, and eye pain [6,7].

Diagnosing ocular toxoplasmosis requires detailed medical history, ophthalmologic examination, and specialized laboratory tests such as serology or PCR [2,8,9]. Treatment typically involves antiparasitic drugs, corticosteroids, and supportive therapies to control the parasite and reduce inflammation [10,11].

Despite the availability of diagnostic and therapeutic methods, ocular toxoplasmosis remains a significant challenge for clinicians. Frequent disease recurrences and severe complications, such as retinal scarring, glaucoma, or retinal detachment, underscore the need for further research into new treatment and prevention strategies [12,13].

Toxoplasmosis, particularly its ocular manifestations, continues to pose a considerable clinical challenge [14]. Advancing knowledge about its epidemiology, pathogenesis, and effective diagnostic and therapeutic approaches is essential to minimizing the disease’s adverse effects and improving patient quality of life [15].

This study presents the complex diagnostic and therapeutic process involved in the reactivation of toxoplasmosis infection following bone marrow transplantation, in the context of an inadequate immune response. This insufficient response may be attributed to the lack of acquired immunity in the stem cell donor. The case highlights the diagnostic challenges and the need for prompt, targeted treatment in immunocompromised patients, particularly those undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Assessing the acquired immunity of both donors and recipients, including the presence of antibodies against parasites and viruses, is a recommended and valuable component of the pre-transplantation qualification process. This practice may help to identify potential risks and prevent post-transplant complications related to infectious reactivations.

A 53-year-old woman presented to the ophthalmology emergency department due to bilateral retinal and choroidal inflammation. In the subjective examination, she reported experiencing scotomas, floaters, flashes, and visual field deficits that had been occurring for approximately one month. She had no prior ophthalmic treatment history. In her medical history, the patient underwent allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, as well as autologous bone marrow transplantation due to multiple myeloma. She is currently under regular hematological supervision. The patient is on the following medications: Encorton 2 × 5 mg, Heviran 800 mg once daily, Fluconazole 200 mg twice daily, Ospen 1500 mg, and Folic Acid 5 mg twice a week. She has reported allergies to sulfamethoxazole.

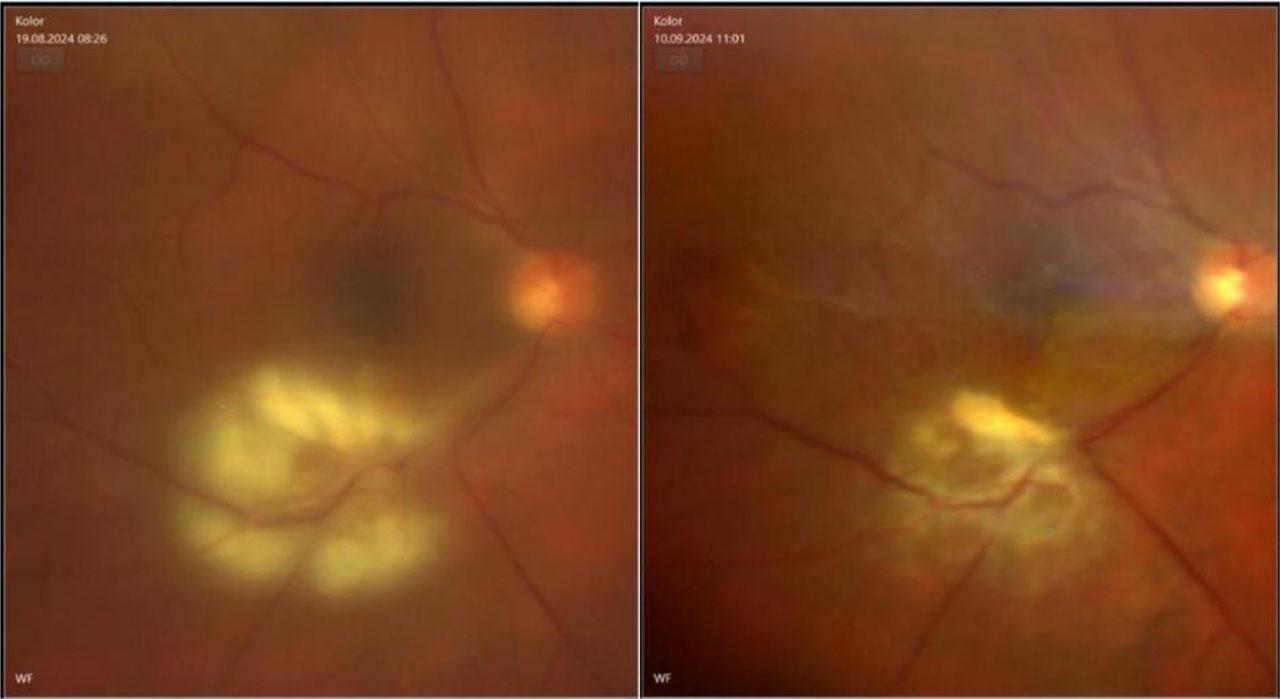

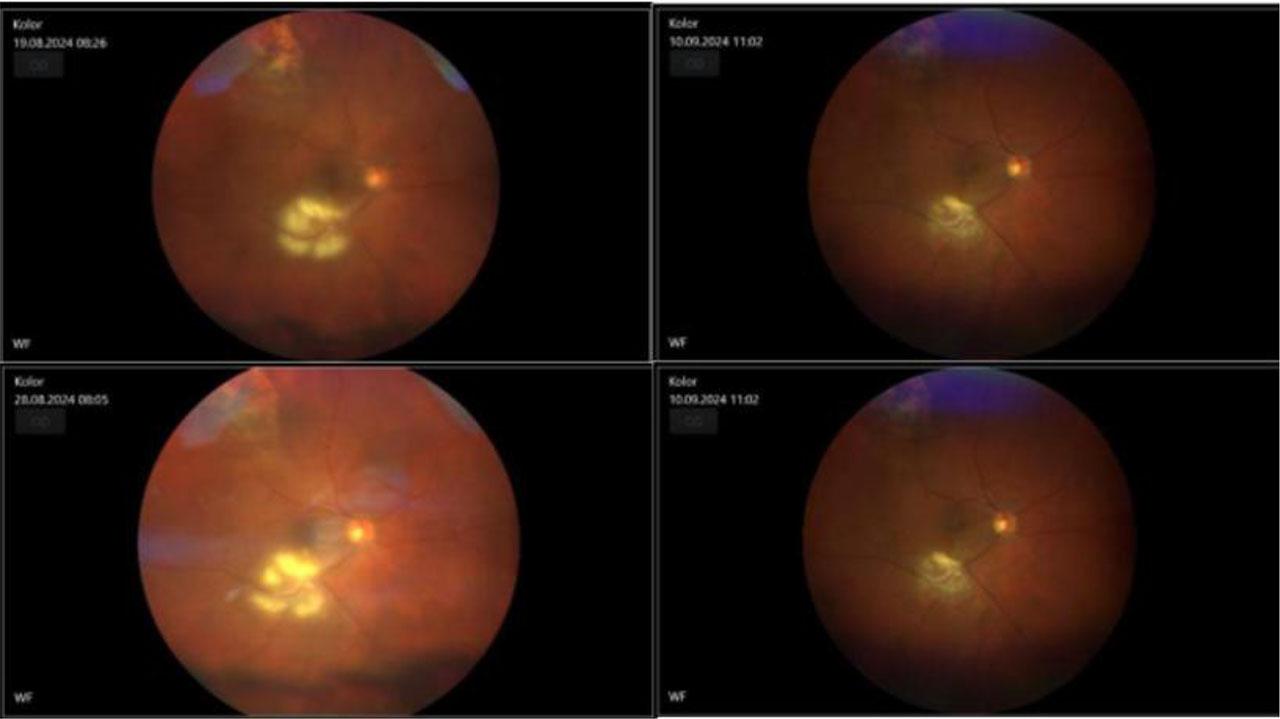

Upon physical examination at the time of admission, the best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was as follows: right eye (RE): 0.25 sc, with a Snellen chart measurement of RE: 0.75 csph +1.0, and left eye (LE): 0.9 sc, with a Snellen chart measurement of LE: 0.5 csph +1.0. Intraocular pressure was measured at 14 mmHg in both eyes. The anterior segment was within normal limits. Examination of the fundus of the right eye revealed obscured details due to a hazy view, with floaters in the vitreous body. There was an inflammatory choroidal-retinal lesion in the inferior temporal vessel measuring 4 dd × 6 dd, accompanied by inflammatory condensation in the vitreous body (reflections obscured). Superiorly, there was a bright, elevated lesion with a small amount of pigmentation (2.5 dd × 2 dd) consistent with post-inflammatory scarring, without retinal detachment [Fig. 1]. In the left eye, floaters were noted in the vitreous body, with an inflammatory choroidal-retinal lesion in the area corresponding to the superior nasal vessel, exhibiting a longitudinal oval shape (5 dd × 3 dd) [Fig. 2].

Fundus photo of the right eye with inflamatory chorioretinal changes –the left side pre-treatment and on the right site there’s an image made after the treatment

Fundus photo of the left eye with inflamatory chorioretinal changes – on the left side pre-treatment and on the right side there’s an image made after the treatment

In additional examinations:

OCT of the macula: Right eye (RE) shows retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) thinning, epiretinal membrane (ERM) with traction, and foveal morphology preserved.

OCT of the optic disc: No swelling of the optic nerve head.

OCT through inflammatory changes: RPE preserved, with visible edema of the retinal layers and hyperreflectivity of the inner retinal layers. [Fig. 3]

OCT through inflammatory changes of the right eye: RPE preserved, with visible edema of the retinal layers and hyperreflectivity of the inner retinal layers and the left eye: normal RPE

Based on the clinical presentation, ocular toxoplasmosis was suspected, with a probable older primary lesion in the right eye. Systemic treatment was initiated with spiramycin and clindamycin. The patient was also referred to for consultation with the Infectious Diseases Department and the Oncology Institute. Information was obtained regarding two potential treatment regimens for toxoplasmosis:

Pyrimethamine + Folic Acid + Sulfadiazine.

Pyrimethamine + Folic Acid + Azithromycin.

Due to the patient’s allergy to sulfamethoxazole, an allergist consulted her and agreed to use sulfadiazine in a low dose under strict clinical supervision. After evaluating the risks and benefits, it was decided to incorporate a second treatment regimen for toxoplasmosis alongside her ongoing hematological therapy. Topical anti-inflammatory agents, bromfenac and dexamethasone, were administered.

Laboratory and imaging studies were conducted, including a hematological, infectious, and rheumatological panel and a head MRI (without significant abnormalities). The following results were obtained: Toxoplasmosis IgG 3596 IU/ml, Toxoplasmosis IgM 314 COI, and IgG avidity 6.6%. The high IgM titer and low IgG avidity suggest that the transplanted hematopoietic cells had not previously encountered the Toxoplasma gondii parasite, resulting in an active immunological response.

In the following days of hospitalization, inflammation was reduced in the anterior chamber and vitreous body, and there was a decrease in choroidal-retinal inflammatory lesions. A decision was made to discharge the patient from the ophthalmology department with a continuation of systemic and topical treatment. Consultations in the infectious diseases and hematology outpatient clinics were recommended.

One week later, further inflammation reduction was observed during a follow-up examination. One month after the initiation of treatment, an increase in liver function tests was noted, leading to a change in the treatment regimen: pyrimethamine and folic acid were discontinued, and fluconazole was replaced with nystatin. Following the normalization of liver function tests, pyrimethamine was reintroduced. After one month, the objective examination revealed continued inflammation reduction, post-inflammatory scarring formation, and visual acuity improvement (BCVA in the right eye: 0.4 csph −2.0D; left eye: 0.9 sc) [Fig. 4]. The patient was regularly monitored every two weeks, with the intervals between follow-ups extended in subsequent months. Visual acuity in the right eye improved to 0.6 csph −0.75 and near vision to 0.5 csph +2.00. An OCT of the macula was performed, revealing RPE thinning and ERM with traction, while the foveal morphology in the left eye remained preserved [Fig. 5].

Fundus photo of the right eye shows changes of inflammation before the treatment and after it

OCT of the macula was performed, revealing RPE thinning and ERM with irregular surface the right eye, while the foveal morphology in the left eye remained preserved

The clinical course of toxoplasmosis depends on various factors, including the type of invasive form of the protozoan, the source of infection, the pathogenicity of the strain, the immune status of the infected individual, and the intensity of the invasion. In individuals with normal immunity, the disease is typically asymptomatic or presents mild symptoms in 85% of cases.

Clinical Forms:

Lymphadenopathic Form: This form is characterized by enlarged lymph nodes, particularly in the cervical, posterior, and occipital regions, with diameters up to 3 cm. In the acute phase, the lymph nodes are painful, but later, they become painless and are not suppurative. Flu-like symptoms may occasionally occur. In approximately one-third of cases, the clinical picture resembles mononucleosis. The lymphadenopathic form is more commonly observed in immunocompetent individuals.

Ocular Form: This involves inflammation of the retina and choroid of the eye. It occurs more frequently in immunosuppressed individuals and cases of reactivation of congenital toxoplasmosis, particularly in the second and third decades of life.

Generalized Form: Symptoms may involve one or several internal organs, such as myocarditis, pneumonia, pleuritis, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, anemia, hemorrhagic diathesis, as well as central nervous system involvement (encephalitis, meningitis, spinal cord inflammation, polyneuropathy).

The presented case study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. Firstly, there is a lack of available information on other similar studies involving the reactivation of ocular toxoplasmosis in patients following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. This limits the ability to compare and place the case within a broader clinical context. The scarcity of such cases in the medical literature highlights the need for further research.

Additionally, the absence of pre-existing ophthalmologic data for the patient makes it difficult to determine whether the retinal inflammatory changes were entirely new or a recurrence of previously existing lesions. The lack of prior ophthalmic documentation also restricts a comprehensive assessment of the disease progression and the effectiveness of the treatment regarding the baseline ocular condition.

Acknowledging these limitations is essential for accurately interpreting the case and for guiding future studies on ocular toxoplasmosis in immunocompromised patients.

Toxoplasmosis in immunocompromised patients can lead to multiple organ failure, graft rejection, and neurological disorders. Ocular toxoplasmosis may result in uveitis, permanent visual field deficits, amblyopia, and blindness. The goal of treatment is to control the inflammatory response and preserve vision.

Seropositive patients in a state of profound immunosuppression should be treated according to the protocol used during the acute phase of toxoplasmosis in the event of symptomatic reactivation of the infection. After the resolution of the acute phase of the infection, long-term prophylactic treatment with extended-release antiparasitic medications, such as cotrimoxazole (trimethoprim with sulfamethoxazole), pyrimethamine with sulfadoxine, or azithromycin, is recommended. Given the potential for relapse, patients should remain under continuous care from an ophthalmologist and an infectious diseases physician.

In preventing toxoplasmosis, it may be beneficial to consider ophthalmologic examinations for patients before scheduled hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, both for recipients and donors. Serological testing for the presence of toxoplasmosis is also advised [16].