Lidocaine is chemically classified as an amide of monocarboxylic acid, formed through the condensation of N,N-diethyl glycine with 2,6-dimethylaniline (Silva et al., 2023). It belongs to the class of local anesthetics characterized by an amide structure (Karnina et al., 2021). Compared to ester-type local anesthetics (such as procaine), lidocaine exhibits greater chemical stability (Garmon et al., 2025). Hydrolysis of ester compounds releases para-aminobenzoic acid, which can trigger allergic reactions in some patients—a phenomenon not observed with amide-type anesthetics like lidocaine (Bina et al., 2018). Like other local anesthetics, lidocaine exerts its effect by targeting sodium channels located on the inner surface of the nerve cell membrane. The uncharged form of lidocaine penetrates nerve sheaths and enters the axoplasm, where it ionizes by forming hydrogen bonds. The resulting cation reversibly binds to sodium channels, keeping them closed and thereby preventing nerve depolarization (Silva et al., 2023; Tsuchiya and Mizogami, 2013). The anesthetic effect of lidocaine may be diminished in the presence of inflammation. This reduction is likely due to decreased local lidocaine concentration because of increased blood flow and/or the presence of inflammatory mediators, which compete for sodium channel binding sites, reducing the drug's efficacy (Beecham et al., 2025).

Lidocaine is available in various formulations, including solutions, hydrogels, creams, and patches, and can be administered topically, subcutaneously, intravenously, or epidurally (Beecham et al., 2025). In semi-solid topical forms such as creams and gels, lidocaine is widely used to numb skin during minor procedures and to alleviate pain or itching caused by sunburn, burns, insect bites or stings, and minor cuts or scrapes (Bahar and Yoon, 2021). Some products containing lidocaine are used in urological procedures to numb the area during the examination (Akkoc et al., 2016), as well as for lubrication during nasal, oral, or throat intubation (Kuo et al., 2010; Sharma et al., 2024). In addition, lidocaine may be used in dental procedures like taking dental impressions (Akhtar et al., 2025). In addition to traditional local pain treatment, lidocaine is used in patches in managing neuropathic pain conditions such as post-herpetic neuralgia (Derry et al., 2014). Patches containing 5% lidocaine are indicated for more severe conditions. They are recommended for treating localized peripheral neuropathic pain—often accompanied by allodynia—as well as central pain resulting from spinal cord compression due to metastatic tumors. These patches are also effective for managing painful conditions such as diabetic neuropathy and persistent postoperative pain following surgeries like thoracotomy, mastectomy, or inguinal hernia repair (Leppert et al., 2018).

Microemulsions are typically characterized as seemingly uniform mixtures composed of water, water-insoluble organic substances, and a mixture of surfactants and co-surfactants (Suhail et al., 2021). The size of the inner phase droplets ranges from 10 to 300 nm (Fink, 2020). The manufacturing process is straightforward and does not require specialized equipment or intensive sonication, thereby reducing production costs. The quality and properties of microemulsion systems are influenced by various factors, including the composition of the oil phase, the choice of surfactants and co-surfactants, their hydrophilic–lipophilic balance, and the chain length of the co-surfactants (Pavoni et al., 2020). These parameters fundamentally determine the type of microemulsion (o/w or w/o) and its stability. Due to their high fluidity, microemulsions are challenging to apply topically; however, this issue can be resolved by increasing their viscosity with gelling agent (Coneac et al., 2015). Microemulsion gels (MEGs) are formed by incorporating thickening agents or biopolymers into the aqueous or oily phases of a microemulsion. This creates a system that merges the advantages of both microemulsions (high solubilization, enhanced drug delivery) and hydrogels (improved stability, controlled release) (Nwankwo et al., 2025).

MEGs offer several advantages over traditional dermatological formulations. These include physical stability, more efficient drug incorporation—including hydrophobic substances dissolved in the oil phase—and the ability to provide controlled release of active ingredients. In addition, they enhance drug absorption through the skin and via transdermal delivery. They are also less greasy, easily washable, and provide a more pleasant application experience for the patient, compared to microemulsions (Song et al., n.d.). Despite these benefits, MEGs have certain limitations, such as suitability primarily for drugs required at low concentrations, poorer absorption of high-molecular-weight molecules, and potential risks of skin irritation or allergic reactions.

This study contributes to the development of effective drug delivery systems, ensuring better drug penetration and bioavailability of lidocaine hydrochloride. The formulation is designed for topical, noninvasive delivery of lidocaine to provide localized pain relief by numbing the skin and underlying tissues. MEG may enhance the permeation of lidocaine into the skin layers, which could lead to a faster onset and improved efficacy of local anesthesia.

Polysorbate® 80 (Tween 80), pure oleic acid, and ethanol (96%) were obtained from CentralChem (Bratislava, Slovakia). Transcutol® (diethylene glycol monoethyl ether), isopropyl myristate, and Poloxamer® 407 (Koliphor® P407) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Cremophor® RH40 was obtained from BASF (Ludwigshafen, Germany). Poloxamer® 188 was obtained from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). Carbopol® 940 was supplied by Thermo Scientific (Geel, Belgium). Lidocaine hydrochloride was obtained from SOLUPHARM® (Melsungen, Germany). Ultra-purified water was prepared directly at the Department of Galenic Pharmacy by Biosan Labaqua Bio (Vrhlika, Slovenia).

Three MEGs were prepared in 10 g quantities with 1% (w/w) of lidocaine hydrochloride solubilized in oil phase, which were as follows: oleic acid in MEG1 and MEG3 and isopropyl myristate in MEG2. The mixture of surfactant (Polysorbate® 80 or Cremophor® RH 40 or Poloxamer® 188) and co-surfactant (ethanol or Transcutol® ) was mixed with the oil phase, and the aqueous phase (purified water or aqueous solution of Poloxamer® 407) was slowly added drop by drop. The composition of the MEGs and the reference gels (Gs) is listed in Tab. 1.

The Composition of MEGs and Gs.

| Component | MEG1 (%) | G1 (%) | MEG2 (%) | G2 (%) | MEG3 (%) | G3 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polysorbate® 80 | 35.54 | 35.53 | - | - | - | - |

| Transcutol® | 17.72 | 17.72 | - | - | - | - |

| Oleic acid | 17.72 | - | - | - | 5.00 | - |

| Purified water | 29.02 | 45.75 | 37.74 | 46.53 | - | 5.00 |

| Isopropyl myristate | - | - | 8.79 | - | - | - |

| Cremophor® RH40 | - | - | 44.03 | 44.03 | - | - |

| Ethanol (96%) | - | - | 9.44 | 9.44 | 25.00 | 25.00 |

| Poloxamer® 188 | - | - | - | - | 25.00 | 25.00 |

| Poloxamer® 407 (20% aqueous solution) | - | - | - | - | 45.00 | 44.00 |

| Carbopol® | - | 1.00 | - | - | - | 1.00 |

G: reference gel, MEG: microemulsion gel

Simultaneously, Gs were prepared by replacing the oil phase with an equivalent amount of purified water. In addition, for G1 and G2, the formulation included 1% (w/w) of the gelling agent—Carbopol®.

Rheological properties of the samples were evaluated using a rotational rheometer (Anton Paar Rheolab QC, Graz, Austria) equipped with a cylindrical measuring unit (CC10). Before measurement, each sample was carefully loaded into the measurement cylinder and the measuring unit was assembled. Samples were allowed to equilibrate at a controlled temperature of 25°C ± 1°C for 15 min to ensure thermal stabilization. Measurements were then performed under controlled shear conditions using predefined rotational speeds. The rheometer was connected to a computer running RheoCompass software (Anton Paar, Graz, Austria), which facilitated real-time acquisition and recording of rheological parameters, as well as automated generation of corresponding flow curves and viscosity profiles.

Texture analysis of the MEG samples was conducted using a Stable Micro Systems TA-XT Plus texture analyzer. The instrument is equipped with a vertically moving sliding arm, to which a cylindrical plastic probe was attached. The test parameters entered in the device software to initiate the analysis were the following: pre-test speed: 5.00 mm/s, test speed: 1.00 mm/s, post-test speed: 5.00 mm/s, compression distance: 5.0 mm (auto force mode), trigger force: 3.0 g, measurement count: two cycles.

Each measurement consisted of two consecutive compression cycles. During each cycle, the probe penetrated the MEG sample, while force, distance, and time data were recorded. The software generated force–distance–time curves for both compression and decompression phases for each cycle. From the recorded curves, key texture parameters were calculated as follows: compressibility (A1, representing the force during the first compression), cohesiveness (ratio of the area under the second compression curve to the first, A2/A1), adhesiveness (A3, the negative force area during probe withdrawal), and strength (F1, the maximum force during compression). Raw strength values of initially measured in grams were converted to Newtons (N) using the equation:

Drug release from the prepared formulations was investigated as a preliminary step in the pharmacokinetic evaluation, since drug release from the dosage form is essential for evaluation of bioavailability.

In vitro release studies were performed using Franz diffusion cells. The system comprised a thermostatic unit controlling the temperature and eight Franz diffusion cells allowing simultaneous analysis of multiple samples. The thermostat maintained the acceptor phase temperature at a constant 35°C ± 1°C to simulate physiological conditions. Each Franz cell consists of a donor and an acceptor compartment separated by a dialysis membrane (Spectra/Por® 4; Spectrum Laboratories, Rancho Dominguez, CA, USA) affixed to the donor side. The acceptor compartment was filled with demineralized water, serving as the receptor medium into which the drug diffused. The thermostatic device ensured continuous circulation of the water to maintain uniform temperature. Magnetic stirrers within each Franz cell continuously agitated the samples to prevent localized drug accumulation near the membrane and ensure uniform diffusion throughout the acceptor medium.

For the test, 1 g of each sample—either MEG or G—was carefully weighed and placed into the donor compartment. Controls included cells containing the corresponding pure base without drug (placebo). Sampling was conducted at 30, 60, 90, 120, 180, and 360 min. At each time point, aliquots were withdrawn from the acceptor medium for quantitative analysis. Drug concentration in each sample was determined spectrophotometrically using a calibration curve previously established for lidocaine. Absorbance values were converted to drug amounts released, enabling construction of release profiles over time.

Four kinetic models were used to describe drug release behaviors. The zero-order model represents drug release at a steady, constant rate regardless of drug concentration, making it ideal for controlled-release systems (Mt = M0 + k0t, where Mt is the drug amount released at time t, M0 is the initial drug amount, and k0 is the release rate constant). First-order kinetics imply that the release rate depends on the remaining drug concentration, commonly applied to immediate-release drugs (lnMt = lnM0 − k1t, with Mt denoting the released drug amount at time t, M0 denoting the initial drug amount, and k1 being the first-order rate constant). The Higuchi model, which is based on Fickian diffusion principles, fits homogeneous matrix systems such as matrix tablets or patches (M = kHt^1/2, where M is the released amount, kH the diffusion constant, and t the time). The Korsmeyer–Peppas model describes drug release influenced by both diffusion and erosion and is suitable for complex profiles like those seen in hydrogels (Mt/Mmax = kKtn, where Mt is the drug released at time t, Mmax the total drug amount, kK the kinetic constant, and n the release exponent) (Krchňák et al., 2025).

All experimental data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). The liberation profiles were compared using one-way analysis of variance.

MEGs were prepared under identical conditions within a single day. The composition of the individual MEG formulations is detailed in Tab. 1. To ensure that Gs contain similar composition to MEGs, the oil phase—essential for microemulsions—was substituted with demineralized water in the gels, since hydrogels do not contain an oil phase. Due to the higher water content, G1 and G3 initially lacked a gel-like structure, necessitating the addition of 1% (w/w) Carbopol® 940. During mixing, Carbopol 940 swelled, leading to the formation of a gel structure.

The surfactants used in the formulations were Polysorbate® 80 (MEG1), Cremophor® RH40 (MEG2), and Poloxamer® 188 (MEG3). Polysorbate® 80 was selected based on the study by Goindi et al. (2016), which describes its favorable emulsifying properties that suggest a reduced need for co-surfactants to form microemulsions. During preparation, physical characteristics of excipients influenced handling. Notably, 20% aqueous solution of Poloxamer® 407, which served as the surfactant-containing aqueous phase in MEG3, exhibited temperature-dependent behavior: it remained liquid when refrigerated, but solidified upon warming to room temperature. This transition facilitated the formation of the gel structure in both MEG3 and G3. Although lidocaine was initially dispersed in the oil phase of MEGs, in some cases, for example, in the preparation of MEG2, drug dissolution was observed only after the addition of surfactant (Cremophor®) and cosurfactant (ethanol, 96%).

It results from a phase transition from the micellar solution to the solid micellar cubic structure. Poloxamers, as copolymers of poly(ethylene oxide) and poly(propylene oxide), can spontaneously form micelles depending on the concentration and temperature, owing to their amphiphilic nature (Bodratti and Alexandridis, 2018). After exceeding the critical micellar concentration and the critical micellar temperature, micelles aggregate into a 3D cubic lattice, which forms the structural basis of poloxamer gels. This aggregation is caused by dehydration of the central hydrophobic polyoxypropylene block, coupled with simultaneous hydration of the lateral hydrophilic polyoxyethylene block in the copolymers (Pereira et al., 2013).

Conversely, Cremophor® RH40, also stored refrigerated, was solid but gradually melted to a semi-solid or liquid state at room temperature. Handling MEG2 and G2 required warming to room temperature before processing because at refrigeration temperature, the samples were too viscous for practical manipulation. No such temperature-dependent behavior was observed with Polysorbate® 80; however, a noted disadvantage was its strong odor, which persisted in MEG1 after formulation.

After preparation, all gel bases showed a slight turbidity that cleared upon standing, resulting in transparent gels. Handling samples containing Cremophor® RH40 was more challenging due to their higher viscosity compared to the other formulations. Lidocaine incorporated readily and dispersed well in all bases. Post-preparation, both MEGs and Gs were stored at 2°C–6°C, with evaluations conducted 24 h after preparation. No structural changes were observed after refrigeration; samples remained clear with consistent gel-like texture.

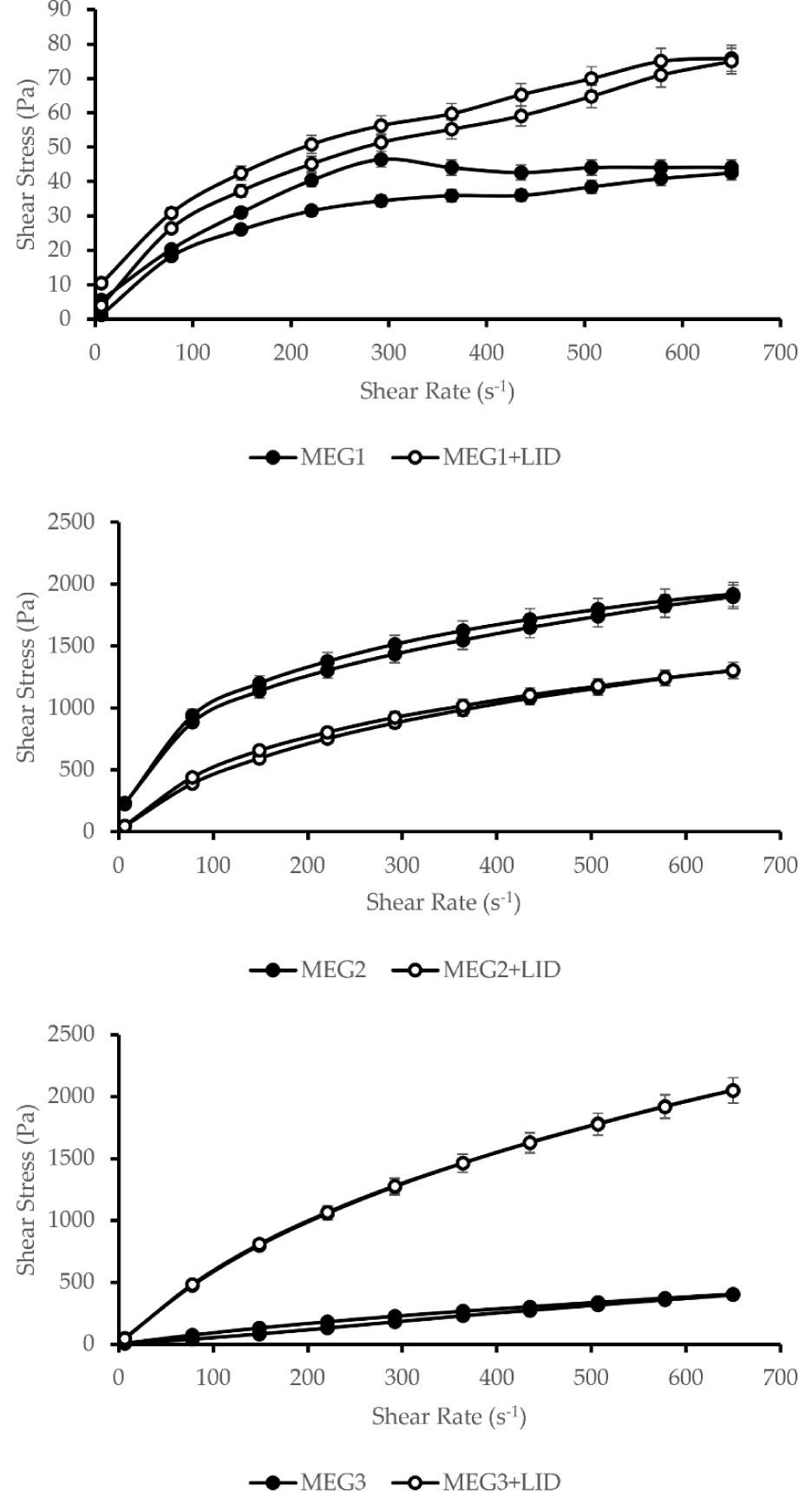

MEGs behaved as time-dependent non-Newtonian fluids. Rheological measurements compared MEGs with and without lidocaine, all tempered at a uniform 25°C and using the same measurement system.

For MEG1, viscosity at a shear rate of 6.45 s−1 was 862.9 mPa·s, with a viscosity change Δη = 664.2 mPa·s between initial and final points. MEG1 containing lidocaine (MEG1 + LID) showed increased viscosity of 1612 mPa·s with Δη = 998.1 mPa·s, exhibiting characteristic thixotropy (Fig. 1). Unexpected behaviors were noted for MEG2. Viscosity at 6.45 s−1 during increasing torque was very high (34,909.5 mPa·s) and slightly higher during descending torque (35,986.5 mPa·s), resulting in Δη = +1077 mPa·s. MEG2 + LID showed lower viscosity values (6,878.1 and 7,294.7 mPa·s) with Δη = 416.6 mPa·s. Several factors might explain this anomaly. Following Hasan's (2019) study on surfactant effects in microemulsions, Cremophor® RH40 can crystallize below its melting point (40°C), resulting in a waxy solid formation at 25°C (Hasan, 2019). This “hardening” phenomenon likely occurred during rheological measurement, complicating lidocaine incorporation. In addition, viscosity depends on microemulsion characteristics such as droplet size and particle interaction. Notably, bicontinuous microemulsions have higher viscosity than oil-in-water or water-in-oil systems (Garti et al., 2005). It is reported that a phase transition may increase viscosity (Solanki et al., 2012). Similar Cremophor®-related viscosity issues were reported by other study when formulating nanocarrier films, where increased stirring speed thickened films, a phenomenon not observed with hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (Kraisit et al., 2024). For MEG3, viscosity at 6.45 s−1 was 948.4 mPa·s during increasing torque and 829.8 mPa·s during decreasing torque, with Δη = 118.8 mPa·s, confirming thixotropic behavior. The behavior of MEG3 had changed from thixotropic to pseudoplastic when lidocaine was added.

Rheological behavior changes induced by LID incorporation.

LID: lidocaine hydrochloride, MEG: microemulsion gel

To summarize, the addition of lidocaine had changed the rheological properties of formulations in different ways, depending on the specific formulation. In all cases, flow indexes (n) were less than 1 (Tab. 2), indicating shear-thinning behavior (Krutof and Hawboldt, 2016). The area of the hysteresis loop decreased after the addition of lidocaine, which means that the viscoelastic properties of the material were reduced.

Indicators of the rheological behavior of the MEGs influenced by LID.

| Formulation | n+ | n− | Hysteresis loop area (Pa s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MEG1 | 0.466 | 0.736 | 4351.71 |

| MEG1 + LID | 0.435 | 0.623 | 3371.33 |

| MEG2 | 0.459 | 0.449 | 42,887.42 |

| MEG2 + LID | 0.727 | 0.711 | 21,012.35 |

| MEG3 | 0.924 | 0.796 | 22,167.66 |

| MEG3 + LID | 0.808 | 0.834 | 3447.42 |

n+ flow index at ascending torque

n− flow index at descending torque

LID: lidocaine hydrochloride, MEG: microemulsion gel

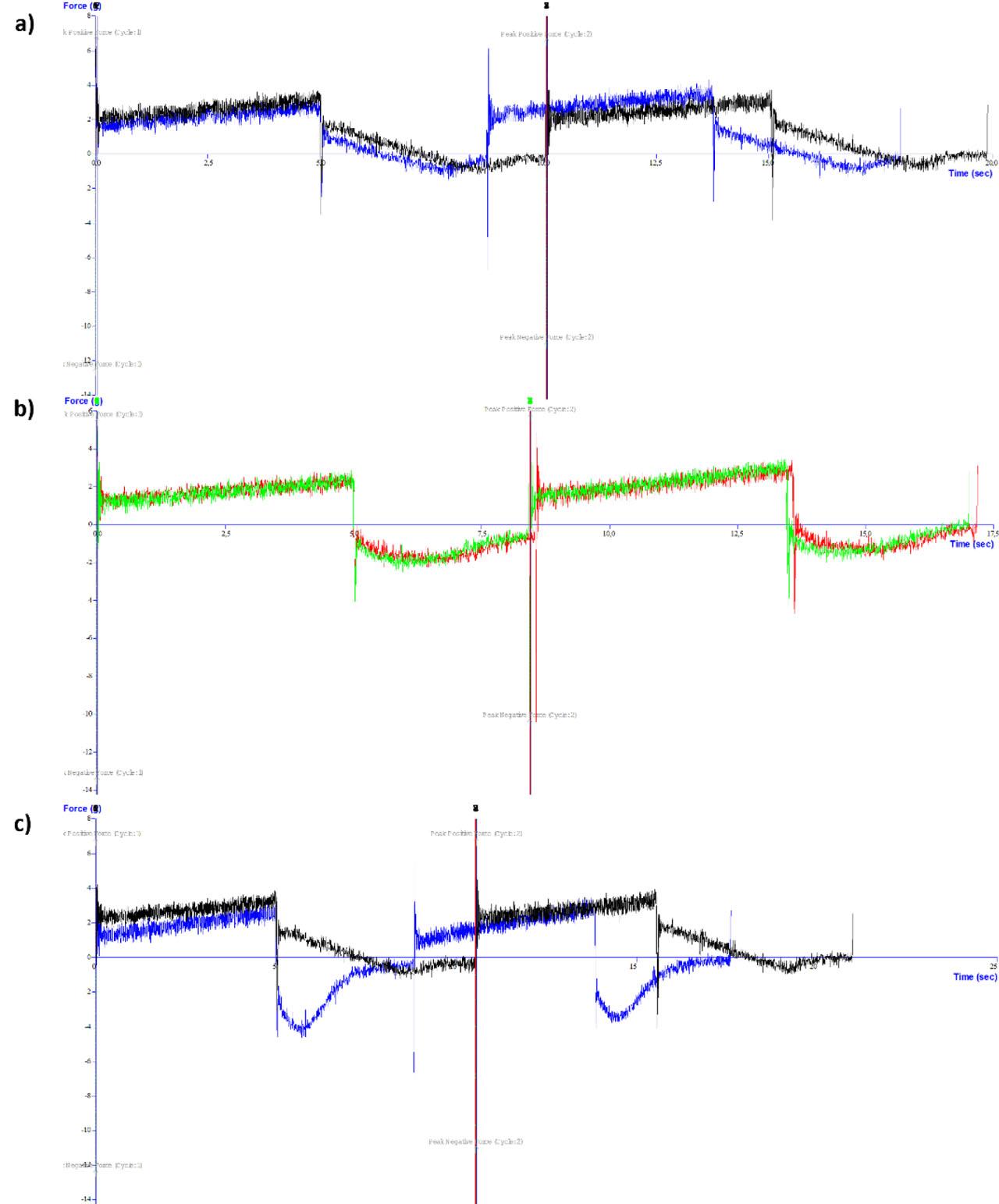

Texture analysis was used to characterize physical parameters of the formulations, including adhesiveness, cohesiveness, compressibility, and strength (Tab. 3). Adhesiveness—reflecting sample stickiness was the highest in MEG2 + LID formulation and the lowest in MEG1. Cohesiveness was greatest in MEG2 and MEG2 + LID, while the lowest cohesiveness was found in MEG1 + LID. Compressibility was highest in MEG1 and lowest in MEG2. Strength was greatest in MEG3 and lowest in MEG2.

The main texture characteristics.

| Sample | Adhesiveness (g s) | Cohesiveness | Compressibility (g s) | Strength (mN) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEG1 | 0.098 | 0.04 | 0.097 | 61.7 |

| MEG1 + LID | 0.104 | 0.04 | 0.050 | 57.3 |

| MEG2 | 0.102 | 1.00 | 0.042 | 48.3 |

| MEG2 + LID | 0.108 | 1.00 | 0.044 | 50.6 |

| MEG3 | 0.098 | 0.12 | 0.059 | 62.5 |

| MEG3 + LID | 0.098 | 0.10 | 0.048 | 52.1 |

These parameters collectively describe gel behavior under external forces. Higher adhesiveness may indicate prolonged retention on the skin, while increased strength, compressibility, and cohesiveness suggest greater resistance to shear during application (Froelich et al., 2016).

On comparing only lidocaine formulations, the MEG2 + LID formulation had the best textural properties, with the highest adhesiveness, stable structure proven by cohesiveness equal to one, and average strength with minimal influence of the drug.

Fig. 2 shows that lidocaine's presence influenced texture characteristics notably only in the formulation of MEG3. As Dumortier et al. (2006) reported, gel strength may increase with the concentration of Poloxamer® 407 and can be affected (i.e., weakened) by the presence of drugs or additives, such as diclofenac, ethanol, or propylene glycol. MEG2 and MEG2 + LID showed nearly identical texture profiles, with minor differences likely due to absence of Carbopol® used as gelling agent in other Gs.

Comparison of texture profiles: a) MEG1 (black) versus MEG1 with lidocaine hydrochloride (blue); b) MEG2 (red) versus MEG2 with lidocaine hydrochloride (green); c) MEG3 (black) versus MEG3 with lidocaine hydrochloride (blue).

As a preliminary step, the absorbance wavelength of lidocaine was determined. The absorbance spectrum of the standard solution (0.1 mg/mL) was recorded over 190–600 nm using demineralized water as the blank. The peak absorbance was observed at 263 nm, consistent with results of other studies (Horie et al., 2010; Sadeqi et al., 2022). The constructed calibration curve displayed linearity with a coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.9951. The equation describing the linearity of the calibration curve (y = 0.0017x + 0.0045) enabled quantitative analysis of the drug content in the samples.

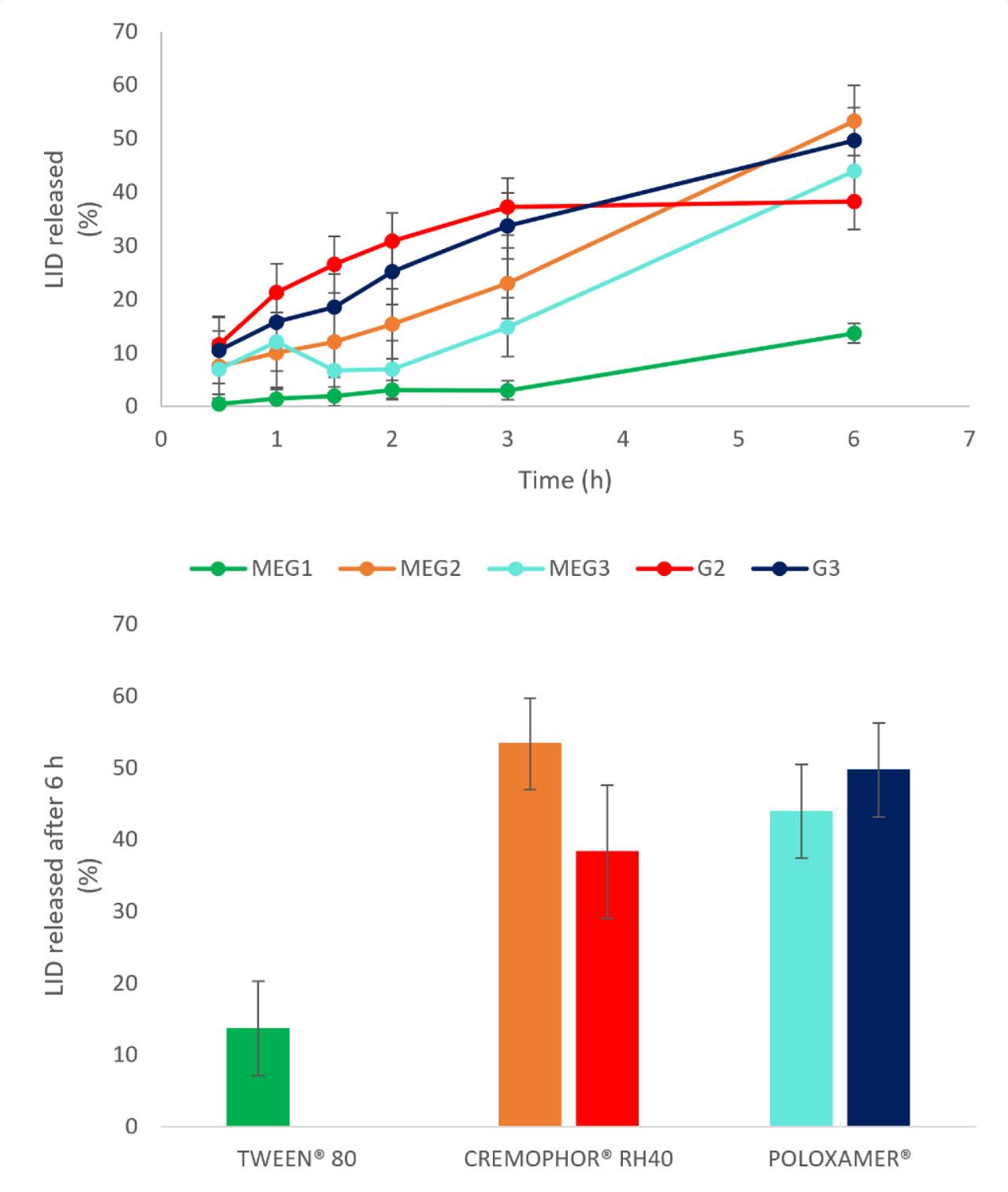

In vitro liberation studies assessed each formulation's ability to release lidocaine over time. All MEGs exhibited almost linear release profile. The fastest release occurred from MEG2, which was possibly associated with temperature-sensitive character of the formulation containing Cremophor® RH40, that is, with a decrease in the viscosity. For gels, the formulation based on Polysorbate® 80 showed minimal drug release, and later time-point samples fell below detection limits, excluding this gel from quantitative results. The other two Gs demonstrated very similar drug liberation profiles. Comparison of total drug amount (%) released in 6 h (Fig. 3) revealed superior release from MEGs containing Polysorbate® 80 and Cremophor® RH40 compared to their Gs. Conversely, Poloxamer®-based gel (G3) showed better liberation than MEG3, likely due to lower sample viscosity.

In vitro liberation profiles of LID from MEGs and Gs and total drug released (%) after 6 h.

Gs: reference gels, LID: lidocaine hydrochloride, MEGs: microemulsion gels

Overall, in two of three cases, MEGs provided improved drug release relative to Gs, supporting the hypothesis that MEGs enhance drug liberation. Similarly, it was reported pseudoplastic flow and superior lidocaine release from MEGs with composition similar to our formulations, compared to commercial gels, suggesting enhanced bioavailability of drugs administered via MEGs (Daryab et al., 2022). Future validation via ex vivo permeation studies using human or animal skin is recommended to confirm these findings.

The kinetic modeling of drug release profiles helps elucidate the underlying mechanisms governing drug release from the formulations studied. The coefficient of determination (R2) indicates how well each model describes the release data. As reported in Tab. 4, lidocaine release from MEG1 is best described by first-order, indicating concentration-dependent release involving diffusion. Lidocaine release from MEG2 and MEG3 fit well to zero-order, which describes a constant drug release rate independent of the drug concentration. Lidocaine release from G2 shows moderate fit mostly with first-order kinetic model. The drug release from G3 is best described by Higuchi and Korsmeyer–Peppas models, indicating mixed mechanisms, that is, combination of diffusion and polymer relaxation mechanisms influencing drug release.

Coefficient of determination (R2) for the kinetic models.

| R2 | MEG1 | MEG2 | MEG3 | G2 | G3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zero order | 0.927 | 0.982 | 0.870 | 0.676 | 0.975 |

| First order | 0.983 | 0.814 | 0.558 | 0.869 | 0.888 |

| Higuchi | 0.834 | 0.908 | 0.750 | 0.824 | 0.991 |

| Korsmeyer–Peppas | 0.952 | 0.935 | 0.584 | 0.880 | 0.991 |

The study focused on the development and characterization of lidocaine MEGs with promising physical and drug release properties for topical local anesthesia. The incorporation of lidocaine into MEGs altered mainly rheological properties. The texture of the prepared formulations remained largely unchanged with the addition of lidocaine. However, in formulations MEG1 and MEG3, a slight decrease in compressibility and strength was observed. The cohesiveness value close to 1 in MEG2 suggests a relatively stable structure that is resistant to mechanical stress. Hysteresis in the rheograms of the formulations indicates that these are time-dependent flow systems, which in one case (MEG3) changes to pseudoplastic, time-independent flow due to the addition of lidocaine. The incorporation of microemulsion systems, particularly those containing Polysorbate® 80 and Cremophor® RH40, proved beneficial by facilitating enhanced in vitro drug release from the formulations.

While the formulations were designed for local anesthesia, delivering anesthetic effect by numbing the skin and underlying tissues, it is important to note that the lidocaine concentration used in the formulations (1% w/w) is lower than that of many marketed products, which typically contain higher local anesthetic doses.