Prostate cancer (PCa) is one of the most diagnosed cancers in the world and is a disease typically characterized by a triggered abnormal uncontrolled cellular growth and proliferation caused by prolonged genetic alterations in the living body (Alison 2001). In 2018, there were 1.3 million new patients diagnosed with PCa in the world (Bray et al., 2018; Malik et al., 2019). Surgery and radiation are used for some advanced stages of the disease, while other options are also used for different cases. Early studies on androgen deprivation in PCa demonstrated the role of androgen receptor in growth and survival (Huggins and Hodges 1941). Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) is an antihormone therapy administered for treating advanced PCa. Initially, significantly high efficacy was observed with ADT; however, most patients suffering from advanced PCa eventually show resistance to this therapy and degenerate to castrate-resistant PCa (CRPC) (Hotte and Saad 2010). In this case, there could be a continuous rise in prostate-specific antigen (PSA) in the serum, progression of the pre-existing disorder, or appearance of new metastasis. Antiandrogen drugs such as enzalutamide, abiraterone, and apalutamide have been approved as second-generation therapies by the Food and Drug Administration, which has increased the survival rate of CRPC patients (Beer et al., 2014; Smith et al., 2018). Alternatively, chemotherapy is a viable choice for treating metastatic PCa and has been shown to increase the survival rate when compared to ADT (Litwin and Tan 2017). The standard chemotherapy agent, docetaxel (DTX), has been used primarily for the management of PCa.

DTX is an effective and commonly administered anticancer drug in clinical practice (Rowinsky 1997). DTX is a semisynthetic taxane that functions by binding to the beta-tubulin subunit of microtubules to cause cell cycle arrest and programmed cell death (Ramaswamy and Puhalla 2006). However, due to its high lipophilicity and low solubility, the major commercial product (Taxotere) that is approved and utilized clinically is formulated in Tween 80 and ethanol as vehicles. Tween 80 is associated with a high risk of eliciting serious side effects in patients, such as neurotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, and allergic reactions (Clarke and Rivory 1999). Furthermore, these formulations are not designed to appropriately entrap DTX in functionalized carriers to improve specificity, targeting, circulation time, and performance. These suggest the need to develop alternative formulations that will improve both efficacy and safety.

Small molecule drugs have been used to target specific miRNAs and can be used to modulate miRNA activities. A natural 2-hydroxy-2,4,4,5,6-pentamethoxychalcone (rubone) has been shown to significantly inhibit PCa by upregulating miR-34a and targeting miR-34a target genes such as cyclin D1 and Bcl-2 (Xiao et al., 2014). Some miRNAs, such as miR-34a, are downregulated in PCa (Singh et al., 2012), and increase in their expressions correlates with a decrease in aggressiveness of the tumor, PSA level, and occurrence of metastases because the miR-34a is involved in the promotion of tumor cell apoptosis, inhibition of tumor metastasis (Wang et al., 2016), and chemoresistance (Fujita et al., 2008).

Targeting bioactive compounds to cancer cells requires exploring specific peculiarities around the cancer cells' characteristics and microenvironment. Receptors for luteinizing hormone releasing hormone (LHRH) are relatively more expressed in human cancer cells than in normal tissues (Liu et al., 2011), and this can also provide active targets for functionalized drug delivery systems.

Entrapment of small molecule drugs within nanocarriers is desired for numerous benefits. Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) are submicron colloidal carriers with solid lipid cores that have been effectively dispersed uniformly in an aqueous solution containing a surfactant/stabilizer. These lipid core matrices are physiologically safe, biodegradable, stable, and can be used to achieve controlled delivery of drugs (Paliwal et al., 2011; Cortesi et al., 2002). SLNs can accommodate a variety of therapeutics including small drug molecules, large biomacromolecules, vaccine agents, and genetic molecules (Paliwal et al., 2011). Other studies involving DTX-based nanoparticles have demonstrated improved cytotoxicity (Sanna et al., 2011; Muj et al., 2023), and the prepared nanosized drug particles enabled effective uptake and increased antiproliferative activity. However, appropriate selection and use of materials that ensure safety, targeting, and natural defense will improve eventual therapeutic outcomes.

In this present study, the main lipid matrix (cetyl palmitate) used for SLN preparation can be evaluated in silico for affinity with low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6 (LRP6), which is highly expressed in PCa (Tahir et al., 2013). LRP6 is a single transmembrane protein that is the major component in Wnt/b-catenin signaling pathway, a vital regulator of tissue development and homeostasis (Cheng et al., 2011; Kelly et al., 2004; Williams and Insogna 2009). Interactions between Wnt proteins and LRP6 proteins lead to downregulation of GSK-3 activity and stimulation of the canonical or β-catenin dependent pathway. This pathway is involved in many diseases including different types of cancers (Clevers 2006; MacDonald et al., 2009).

The aim of this research is to develop functional SLNs of DTX for improved efficacy against PCa and exploration of lipid- and protein-based targeting.

DTX (Sigma Aldrich, USA), n-hexadecyl palmitate (HDP; cetyl palmitate) (TCI, Tokyo, Japan), phosphatidylcholine (Avanti, USA), Soluplus® (polyvinyl caprolactam–polyvinyl acetate–polyethylene glycol graft copolymer; BASF Pharma, Germany), Rubone (Sigma Aldrich, USA), LHRH (Biomatik, Canada), Brij® O10 (polyethylene glycol oleyl ether; Sigma Aldrich, USA), Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) enriched with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% antibiotics (streptomycin and penicillin), phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA), and trypsin (Gibco®, Life Technologies/Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) were used in the study.

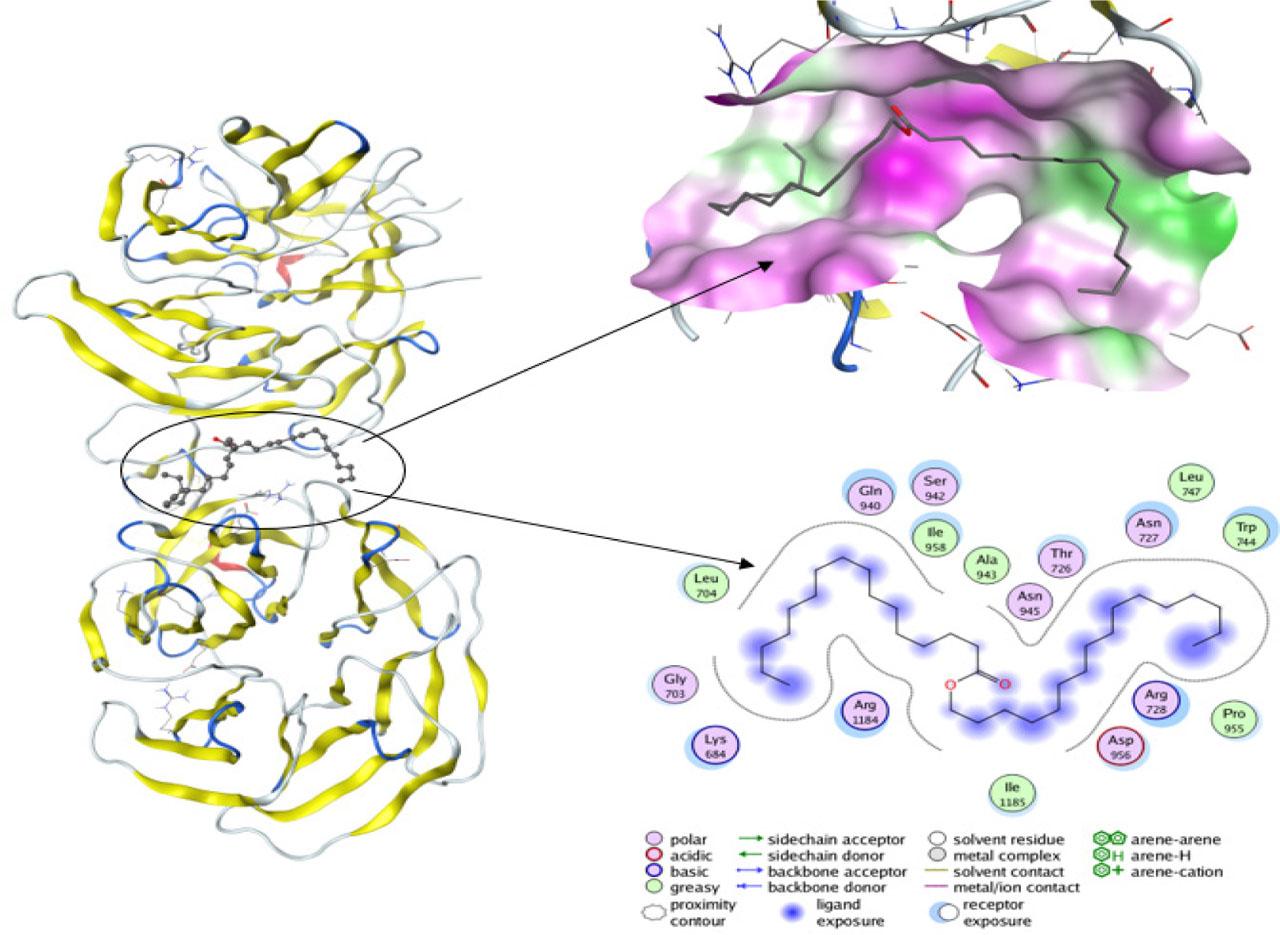

Molecular operating environment (MOE) software was used to carry out docking calculations and scoring of resulting receptor–ligand complexes in this study (Chemical Computing Group 2010). The three-dimensional structure of LRP6 consisting of three and four domains was retrieved from protein databank (PDB ID: 4A0P) (Berman et al., 2001) and loaded into MOE. All the heteroatoms, including water and non-essential small molecules, were removed and then missing side chains and charges were added before being protonated at a temperature of 300 K, salt concentration of 0.1, and pH 7 in implicit solvated environment. Finally, the system was energy minimized to a gradient of 10−6 kcal/mol using molecular mechanics MMFF94 force field (Halgren 1996). In addition, the chemical structure of cetyl palmitate was built using the 3D builder interface in MOE and energy minimization carried out as stated earlier. The region defined by previous report (Chen et al., 2011) as the LRP6 ligand-binding site was enclosed by grid box of sizes 9.8784, 7.5684, 7.1065 Å3, and the DockTool implemented in MOE was used to perform both ligand placement to generate 10 ligand poses (Triangle Matcher) and scoring (London dG) of each of the poses.

Cetyl palmitate (HDP) (20 mg) and phosphatidylcholine (5 mg) were weighed out into a 5 mL bottle and co-melted for 5 min at 90 °C with mixing. The lipid mix was removed from the heat source, cooled to 25 °C, and 5 mg of DTX was added. A solvent mix of ethanol (800 μL) and methanol (400 μL) was transferred into the container with the lipid and drug mix. The closed lipid phase was then maintained at 60 °C in a heating instrument.

Soluplus (20 mg) and Brij O10 (10 mg) were dispersed in 1.94 mL of distilled water, and this aqueous phase was maintained at 60 °C with continuous stirring. After 10 min of heating, a glass syringe (thermostable) was used to withdraw the lipid/drug solution, and the solution was quickly transferred to the aqueous phase dropwise with continuous stirring.

The primary emulsion obtained was maintained at 60 °C with continuous stirring for 5 min. The primary emulsion was then subjected to probe sonication for 10 min at 30% amplitude using a Qsonica instrument/probe sonicator (Qsonica, USA). Thereafter the SLNs' dispersion was cooled to 25 °C. This preparation was labeled DSLN1. In addition, DSLN2, DSLN3, and DSLN4 batches were prepared based on components/ingredients given in Table 1. A blank SLN was also prepared without DTX as the control. For batches DSLN2, DSLN3, and DSLN4, 15, 20, and 20 μg of rubone was added to the lipid phase before emulsification, respectively. A stock solution of rubone in ethanol/methanol (1:1) was prepared (0.5 mg/mL), and aliquot corresponding to the required rubone content was taken. For DSLN4 batch, which contained LHRH peptide, a 1 μg/μL (1 mg/mL) stock LHRH solution was prepared in ethanol solution. Twenty microliters (corresponding to 20 μg) of LHRH solution was incubated with the sonicated SLN dispersion at 4 °C for 24 h. The positively charged LHRH (mainly due to arginine) is expected to bind to the surface of the SLN containing negatively charged domains.

Formulation of docetaxel solid lipid nanoparticles.

| Ingredient | BSLN | DSLN1 | DSLN2 | DSLN3 | DSLN4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Docetaxel | --- | 5 mg | 5 mg | 5 mg | 5 mg |

| Rubone | --- | --- | 15 μg | 20 μg | 20 μg |

| Cetyl palmitate | 20 mg | 20 mg | 20 mg | 20 mg | 20 mg |

| PC | 5 mg | 5 mg | 5 mg | 5 mg | 5 mg |

| Brij O10 | 10 mg | 10 mg | 10 mg | 10 mg | 10 mg |

| Soluplus | 20 mg | 20 mg | 20 mg | 20 mg | 20 mg |

| LHRH | --- | --- | --- | --- | 20 μg |

| Water qs | 2 mL | 2 mL | 2 mL | 2 mL | 2 mL |

BSLN: blank solid lipid nanoparticle, LHRH: luteinizing hormone releasing hormone, PC: phosphatidylcholine

A 100 μL aliquot of formulated SLN dispersions was diluted with distilled water to 1 mL and transferred to a quartz cuvette. The particle size of test samples was evaluated using a Malvern nanosizer/zetasizer (Malvern, UK). Polydispersity index was obtained simultaneously. The measurements were obtained in triplicates and presented as average ± ± standard deviation.

In the study of surface charges, a 1 mL aliquot of each diluted test sample was transferred to a folded capillary cell (DTS 1070) and zeta potential was measured by the Malvern zetasizer. The instrument also simultaneously measured the conductivity of the formulation. These measurements were in triplicates and presented as average ± ± standard deviation.

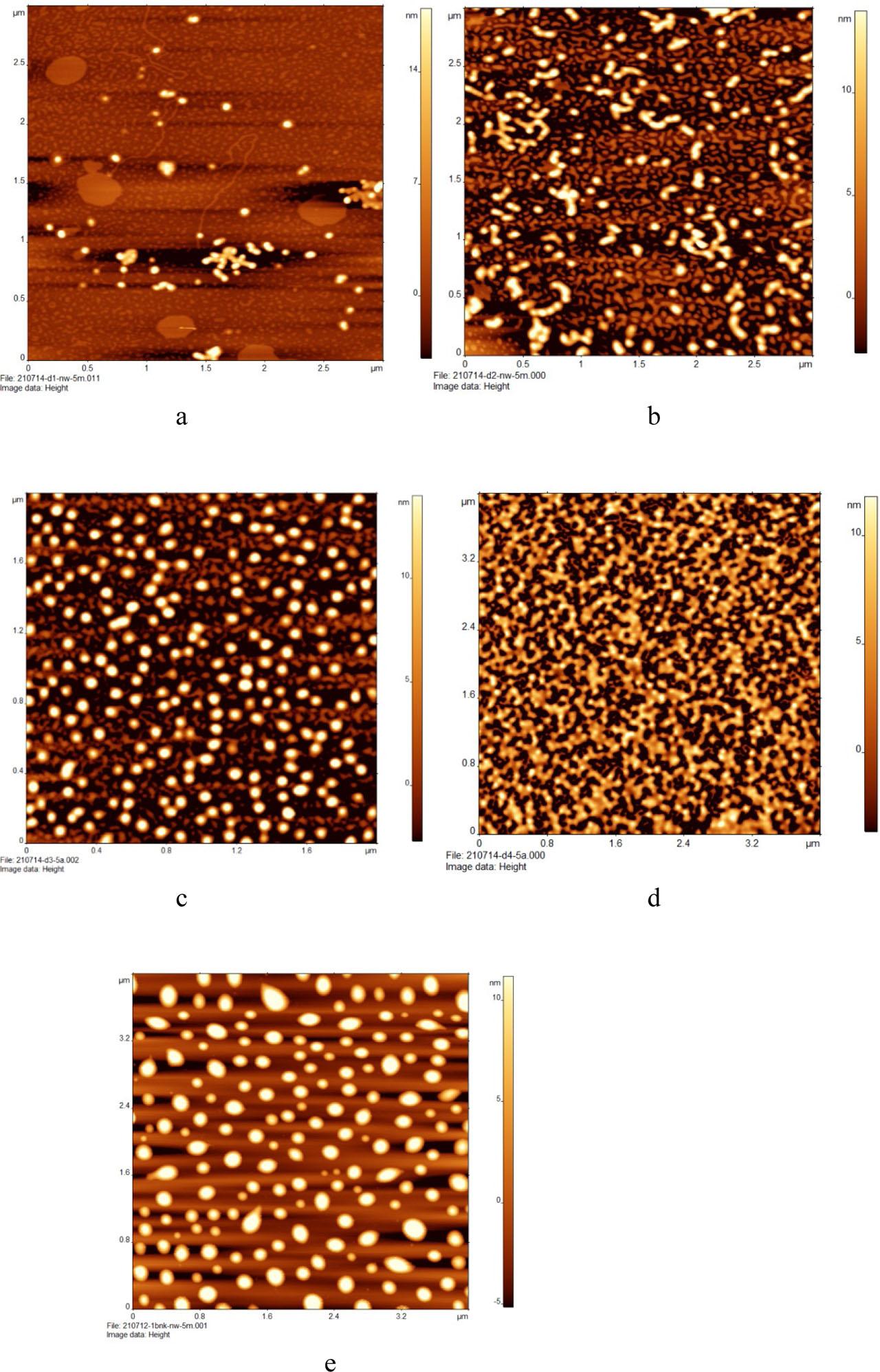

The particle shape of the dispersions was examined using atomic force microscopy (AFM). Samples were diluted in distilled water and deposited onto a piece of mica or modified mica. Freshly prepared mica was modified with 1-(3-aminopropyl)-silatrane (APS) to obtain the modified mica (APS mica) as previously described (Shlyakhtenko et al., 2003; Lyubchenko et al., 2014). After a brief incubation, drops of deionized water were added to deposited samples and dried with a gentle flow of argon. Images were obtained with the Multimode Nanoscope IV system (Bruker Instruments, Santa Barbara, CA, USA) in Tapping Mode at ambient conditions. Silicon probes RTESPA-300 (Bruker Nano Inc., CA, USA) set at a resonance frequency of ~300 kHz and a spring constant of ~40 N/m were used for AFM imaging at a scanning rate of about 1 Hz. FemtoScan software package (Advanced Technologies Center, Moscow, Russia) was utilized for processing the resulting images.

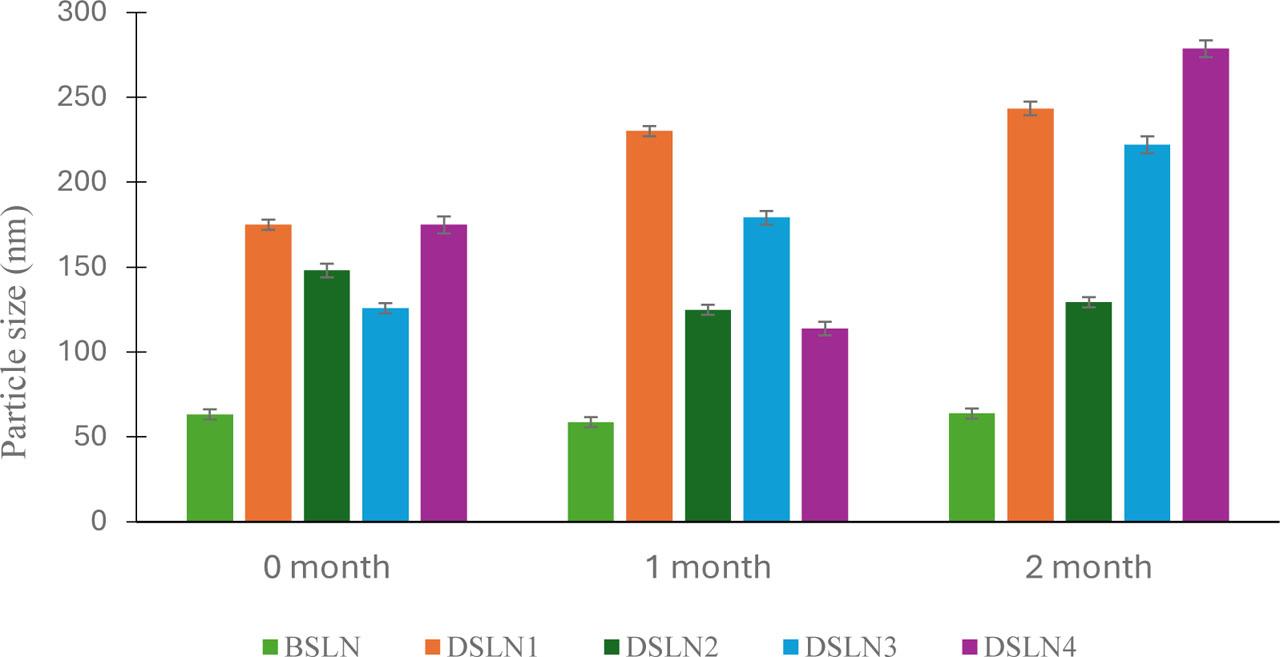

The nanoformulations were stored at 25 °C (room temperature), and particle size was assessed every month for 2 months. Formulations stored at 4 °C were assessed for particle size and polydispersity index after 2 months.

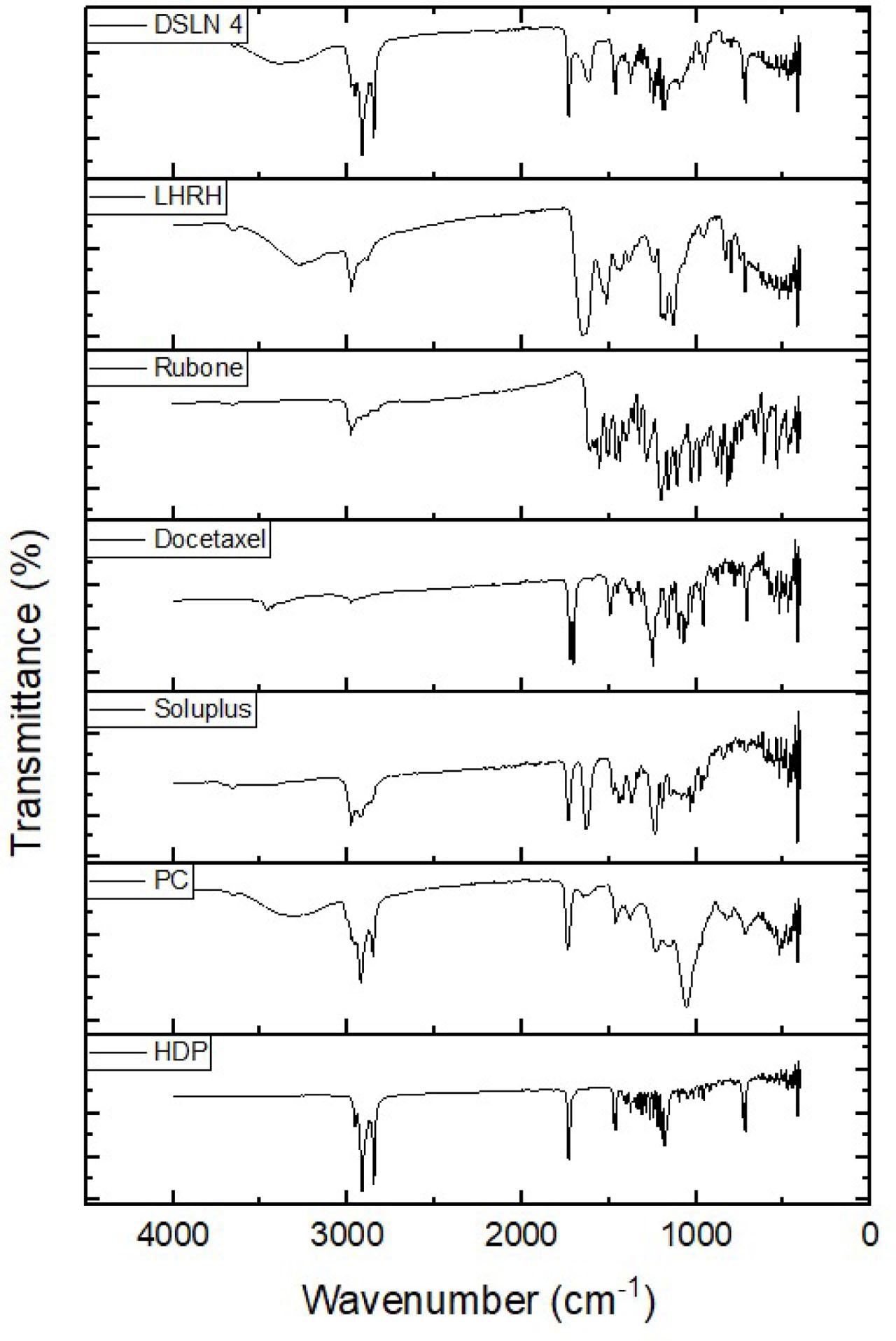

The compatibility of the ingredients within SLNs was evaluated by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. Ten milligrams of each test sample (ingredients and dried formulation) was analyzed using the PerkinElmer spectrum FTIR spectroscopy instrument (Waltham, USA). Analysis of the powder samples was done over a scan range of 400–4000 cm−1 in % transmittance mode.

DTX standard calibration curve was established by preparing serial dilutions of stock DTX solution in acetonitrile:water (70:30). Reverse phase high-performance liquid chromatography (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) was performed using acetonitrile:water (70:30) mobile solvent system, C18 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, Inertsil ODS) as the stationary phase, solvent injection volume of 10 μL, a flow rate of 1 mL/min, and detection wavelength of 230 nm.

To evaluate content, loading, or entrapment, 200 μL of each SLN formulation was centrifuged for 5 min at 14,000 rpm and 25 °C. The supernatant was collected after two cycles. Hundred microliters of the supernatant was measured and 200 μL of acetonitrile was added. The mixture was filtered with a 0.22 μm filter. The clear test samples were analyzed using HPLC to obtain the free drug. Another 200 μL of the formulation was mixed with 200 μL of ethanol and stored closed for 48 h to extract the total DTX. Thereafter, 200 μL of acetonitrile was added and the mixture was filtered with a 0.22 μm filter before the assay. Entrapment efficiency and loading capacity were calculated from equations 1 and 2, respectively;

DTX-loaded SLN dispersions (1 mL each) were enclosed inside a dialysis membrane (Spectra/Por®7; Spectrum laboratories Inc., CA, USA) sealed at both ends (available surface area is 19.32 cm2) with MWCO of 3,500 Da. The dialysis bag was suspended in 30 mL of PBS (pH 7.4) containing 0.1% Tween 80 maintained at 37 °C and 100 rpm. A 250 μL aliquot of test sample was withdrawn from the medium for each batch at different time periods of 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 24, 48, 72, 96, and 144 h, respectively. The test samples were analyzed using a ultraviolet (UV)/visible (VIS) spectrophotometer (Spectramax Me5; CA, USA) with UV detection at 230 nm for DTX after standard calibration.

The flux of DTX across the membrane was calculated from the slope of the plot of amount of drug permeated per square centimeter of dialysis membrane against time using linear regression analysis. The steady-state flux (J) was determined using Equation 3:

Permeability coefficient was obtained from Equation 4:

The similarity factor (f2) was used to measure the similarity between the different drug release profiles of the nanoformulations and pure drug dispersion. This statistical parameter (Equation 5) is a logarithmic reciprocal square root transformation of the sum of squared error.

DU 145 PCa cell lines were passaged in DMEM culture media supplemented with 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 10% FBS (Gibco) in a humidified incubator at 37 °C. The DU145 PCa cells in enriched DMEM were plated in a flask (lysine coated) and incubated for 4 days using the growth medium.

Thereafter, the medium was removed and the cell-attached flask was washed with PBS (2 × 3 mL). Trypsin (2 mL) was added to the flask and placed in the incubator for 10 min to detach the cancer cells from the inner surface of the flask. The enriched DMEM medium (5 mL) was added and mixed gently with the flask content. The medium (containing the cells) was pipetted into a 15 mL centrifuge tube and the cell suspension was centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 min. The cells settled at the bottom of the tube and the supernatant was discarded. Fresh medium (5 mL) was added and mixed with the cells. Briefly, 10 μL of the cell suspension was transferred to a microtube and 10 μL of trypan blue stain was added and mixed. One drop of the mixture was placed in the slide and inserted into a cell counter. A seeding of 50,000 cells/well was done in a 24-well plate. Five hundred microliters of medium seeded with cells was introduced into each well of the 24-well plate and stored in the incubator at 37 °C for 24 h. Then, serial dilutions of pure DTX solutions in DMSO were prepared. Varying concentrations were prepared, such that 5 μL of the drug in DMSO solution gave the desired drug concentration after introducing it into the seeded medium in the 24-well plate. After 24 h of storing the cell suspension in wells inside the incubator, 5 μL aliquot of each DTX test sample of varied concentration was introduced into designated well columns in the plate and incubated for 48 h.

The 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5 diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) solution was prepared in PBS, and 20 μL of this solution was added to each well to obtain approximately 0.5 mg/mL MTT concentration within the media (500 μL) in each well. The 24-well plate was incubated for 4 h, and the medium was carefully removed while leaving the settled insoluble crystals/particles formed. Two hundred microliters of DMSO was introduced to each well to dissolve any insoluble formazan crystal present. The absorbance of the solution was read using the BioTek® plate reader (Epoch) at 570 and 630 nm. The results obtained were used to establish the inhibitory concentration for the cytotoxicity study of the DTX nanoformulations.

MTT assay was then used to evaluate the % viability of the cells in the presence of DTX nanoformulations. In the MTT assay using DTX DMSO solution, DSLN1, DSLN2, DSLN3, and DSLN4, 5 μL of each formulation was added to each well during the study to obtain 850 nM drug concentration in the well. Cell viability was calculated using Equation 6 and comparisons were made:

Two molecular entities are said to interact favorably if the binding free energy of their molecular complex structure gives a negative value (Ibezim et al., 2017, 2019). Flexible ligand protocol was used to assess the affinity of cetyl palmitate for LRP6; results revealed that cetyl palmitate formed a stable complex with the lipoprotein with binding free energies of −8.16 kcal/mol (Fig. 1). This is expected, given the preponderance of amino acids with hydrophobic side chain surrounding the surface of the LRP6 ligand-binding pocket and the nonpolar nature of the test compound. Apparently, van der Waals forces seem to be the major driver behind the binding interaction. However, the ester moiety of cetyl palmitate and the protein residues may infer the presence of polar contacts. The extracellular domain of LRP6 receptor is important in interactions with different proteins that facilitate pathway activities. The interaction site of LRP6 and Dickkopf-related protein 1 is commonly considered as the binding region for molecular docking (Rismani et al., 2018).

Binding pockets detected in the crystallographic structure of LRP6 protein, which are located between two main b-propeller domains with docked cetyl palmitate.

The observation that high expression of LRP6 is associated with PCa characterized by increased cell proliferation (Tahir et al., 2013) confirms the need to understand the binding affinity between LRP6 and the bulk lipid material used in preparing the SLN (in this case, cetyl palmitate [n-HDP]), which may improve the targeting and accumulation of the SLNs around PCa cells. LRP6 is a Wnt coreceptor, and its altered expression leads to abnormal Wnt protein activation, cell proliferation, and tumorigenesis (Wang et al., 2018).

The particle size, polydispersity, zeta potential, and conductivity of the SLN dispersions were analyzed and are presented in Table 2. The drug-loaded particles were less than 200 nm in size, which conforms with most clinically approved nanomedicines (Uster et al., 1998; Gradishar et al., 2005; Hoshyar et al., 2016). In anticancer therapy using nanomedicines, the drug particle size affects drug biodistribution, tumor penetration and saturation, cellular internalization, and clearance from the biological system and, consequently, therapeutic outcome (Davis et al., 2008; Jiang et al., 2008). Effective accumulation of the solid lipid particles in the tumor microenvironment by passive delivery exploits the enhanced permeability and retention effect made possible by the abnormal proliferation and vasculature within the tumor site (Miao et al., 2015; Setyawati et al., 2017).

Particle size, polydispersity index, zeta potential, and conductivity.

| Formulation | Particle size (nm) | Polydispersity index | Zeta potential (mV) | Conductivity (mS/cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSLN | 63.26±3.0 | 0.087±0.01 | −14.53±2.0 | 0.087 ± 0.002 |

| DSLN1 | 174.93±3.0 | 0.344±0.06 | −14.33±0.5 | 0.091±0.001 |

| DSLN2 | 148.03±4.0 | 0.201±0.01 | −8.2±0.3 | 0.161±0.002 |

| DSLN3 | 125.77±3.0 | 0.237±0.01 | −9.27±0.2 | 0.113±0.001 |

| DSLN4 | 174.87±5.0 | 0.393±0.02 | −7.35±2.2 | 0.115±0.002 |

BSLN: blank solid lipid nanoparticle

The size of the nanoparticles increased as the carrier was loaded with therapeutic agents, from blanks of 63.26 nm size to DTX-loaded nanoparticles with a size range within 126–175 nm.

The use of unique surface-active agents and polymers allowed a physicochemical and thermodynamic balance at interfaces that facilitated the generation of particles of desired sizes that are stable. The combination of polyoxyethylene (10) oleyl ether (Brij O10) and polyvinyl caprolactam–polyvinyl acetate–polyethylene glycol graft copolymer (Soluplus) is beneficial since Brij O10 provides the surface activity necessary for creation of the lipid nanoparticles and its changing lipid/aqueous solubility with temperature may be crucial for generating small particles, while Soluplus solubilized the drug and formed micelle structures in the aqueous-based dispersion (Tanida et al., 2016). The inclusion of phospholipid provides a balance of lipophilic and hydrophilic emulsifying entities.

The surface charge on NPs is usually measured as the zeta potential. The blank NPs have a surface charge of −14.53 mV; however, DTX-loaded SLNs DSLN1, DSLN2, DSLN3, and DSLN4 have zeta potentials of −8.20, −9.27, and −7.35 mV, respectively, which are within the ±10 mV range regarded as approximately expressing neutral surface charge (Li and Huang 2008). This property can improve the circulation time of the nanoparticles, in addition to the effect of polyethylene glycol moieties in the polymer and surfactant used in the formulation.

The effect of storage at 25 °C on particle size is presented in Fig. 2. Some formulations, such as DSLN1, showed significant increase (p < 0.05) in sizes from 175 to 243 nm, whereas DSLN3 and DSLN4 increased in size from 126 to 222 nm and from 174 to 278 nm, respectively. Others did not show any significant changes. Despite these changes, most of the formulations still had particle sizes below or around 200 nm. After storage at 4 °C, DSLN3 did not show significant changes, whereas size reduction was observed in DSLN4 (Table 3). Small changes in polydispersity index were observed after storage at 4 °C for 2 months; this could be attributed to particle brittleness in cold conditions.

Time-dependent particle size of docetaxel nanoformulations at 25 °C

Effect of 2 months storage at 4 °C on particle size and polydispersity index.

| BSLN | DSLN1 | DSLN2 | DSLN3 | DSLN4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Particle size (nm) | 61.8±0.2 | 406.5 ±8.8 | 159.7 ±2.5 | 139.6 ±0.9 | 123.7 ±2.6 |

| Polydispersity index | 0.079 ±0.003 | 0.472 ±0.020 | 0.189 ±0.007 | 0.208 ±0.008 | 0.205 ±0.003 |

BSLN: blank solid lipid nanoparticle

The nanoparticles were spherical as shown in Fig. 3. This is expected since the nanoparticles are basically solidified spherical lipidic droplets in the aqueous continuous phase of primary emulsions. The shape of nanoparticles has been identified to affect circulation time, biodistribution, cellular uptake, and drug targeting in cancer drug delivery (Champion et al., 2007; Venkataraman et al., 2011). Other workers have earlier shown that in certain cases, cellular uptake is higher with spherical nanoparticles compared to ellipsoids, nanodiscs, nanorods, or worm-like micelles (Zhang et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2012; Paul et al., 2013; Shimoni et al., 2013; Champion and Mitragotri 2009). However, nonspherical nanoparticles have shown longer circulation time and improved biodistribution. The spherical shape of the nanoparticles favors internalization. Shape anisotropy and initial orientation of the nanoparticles are important in the interactions between each particle and lipid bilayer of biological barriers. The penetrating capability of nanoparticles depends on the contact area between each particle and lipid bilayer and the local curvature of the particle at the contact point (Liu et al., 2012).

Images showing shapes of DSLN1 (a), DSLN2 (b), DSLN3 (c), DSLN4 (d) and BSLN (e) nanoparticles.

The FTIR spectra are presented in Fig. 4. This FTIR study focused on analysis in the mid-IR spectrum. The individual spectrum of each solid ingredient and a formulation (DSLN4) are presented in Fig. 4. Broad band at 3570 cm−1 observed in the spectra of phosphatidylcholine, LHRH, and DSLN4 indicates the presence of -OH group with related peaks also observed in the fingerprint region. The spectra also showed methyl (-CH3) stretches at 2970–2860 cm−1 for cetyl palmitate (HDP), phosphatidylcholine, Soluplus, rubone, and DSLN4, with the stretch in HDP spectrum showing high similarity to that of the formulation since HDP formed the bulk of the nanoparticle matrix. LHRH also showed stretches and bends associated with amide/amine N–H around 3280 cm−1(short peak) and 1645 cm−1(long peak).

FTIR spectra of docetaxel nanoparticle components.

Methoxy groups were detected in rubone with stretches from 2812–2842 cm−1 and a peak at 2924 cm−1, while Soluplus showed a peak at 2840 cm−1. Furthermore, peaks at around 1700 cm−1 indicating carbonyl groups were observed in DTX, HDP, phosphatidylcholine, Soluplus, and DSLN4.

The results clearly showed that there was no chemical interaction between the components of the formulation; therefore, chemical compatibility was inferred.

The entrapment efficiency of DSLN1, DSLN2, DSLN3, and DSLN4 formulations was 73%, 80%, 84%, and 81.2%, respectively, whereas the drug loading capacity was 9.3%, 10.2%, 10.8%, and 10.4%, respectively (Table 4). Formulations containing rubone in combination with DTX (DSLN2, DSLN3, and DSLN4) showed higher DTX entrapment efficiency and loading capacity than the formulations without rubone (DSLN1). This behavior could be caused by different factors. Hydrogen bonding may exist between DTX, rubone, and phosphatidylcholine, which may increase the drug entrapment. In addition, reduced zeta potential and smaller particle size shown by the corresponding nanomedicines could have increased the amount of entrapped DTX.

Drug loading and entrapment for docetaxel-based nanoparticles.

| Formulation | Entrapment efficiency (%) | Drug loading capacity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| DSLN1 | 73.00 ± 3.0 | 9.30 ± 0.35 |

| DSLN2 | 80.00 ± 2.0 | 10.20 ± 0.13 |

| DSLN3 | 84.00 ± 3.0 | 10.80 ± 0.09 |

| DSLN4 | 81.20 ± 2.0 | 10.40 ± 0.06 |

In general, the high drug entrapment achieved was facilitated by the lipid matrix, which improved the solubilization and encapsulation of the poorly aqueous soluble DTX. The use of binary amphiphilic emulsifying/solubilizing agents also eased the process. The entrapment efficiency obtained using this approach was higher than drug entrapments reported in other related studies (Sanna et al., 2011).

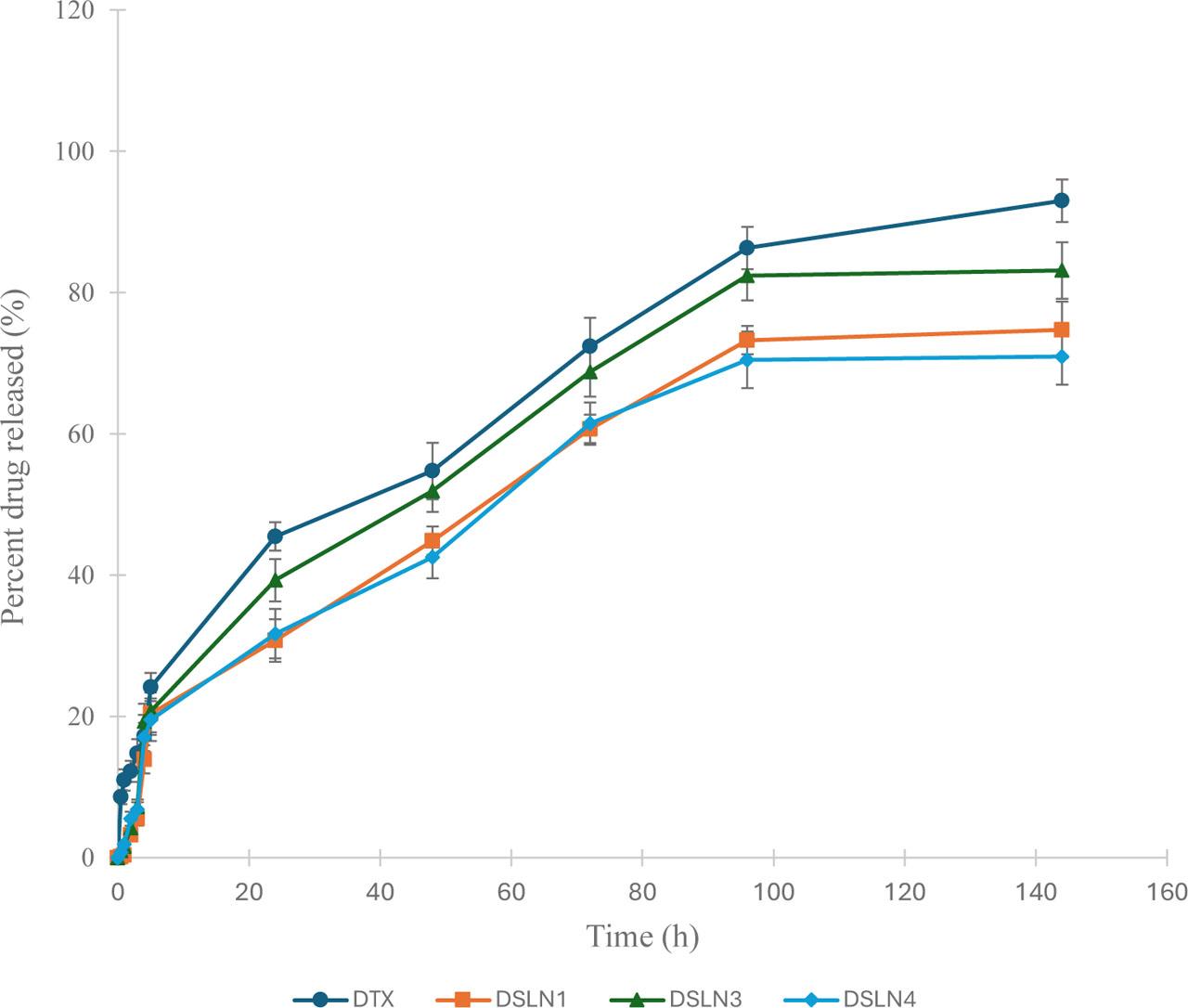

The release profile of DTX (Fig. 5) from the different formulations and pure drug dispersion showed a gradual rise in cumulative drug released from the nanomedicines that diffused through the semi-permeable membrane. As expected, the pure drug dispersion released more drug content, whereas DSLN3, which had no LHRH, showed the highest drug release profile among the formulation series. The absence of LHRH at the surface of the nanoparticles (DSLN3) may have facilitated improved DTX delivery since there was no macromolecule to obstruct the release and permeation of the drug. Furthermore, this formulation containing DTX (0.25% w/w), rubone (20 μg, 0.001% w/w), HDP (1% w/w), phosphatidylcholine (0.25% w/w), Brij O10 (0.5% w/w), and Soluplus (1% w/w) had the smallest particle size and surface area, which may increase the rate of drug release and permeation through the pores of the dialysis membrane compared to other dispersions of nanoparticles. This agrees with the general notion that smaller particle sizes promote permeation through membrane barriers, whether synthetic or biological. The similarity factors obtained from binary comparisons of pure DTX dispersions and formulations DSLN1, DSLN3, and DSLN4 are 35.8, 53.8, and 41.2, respectively. The drug release and diffusion profiles of the pure DTX dispersion and formulation DSLN3 were considered similar since the similarity factor of 53.8 was greater than 50 (f2 > 50). The flux or diffusion flow of DTX through the semi-permeable membrane is presented in Table 5. The flux of DSLN3 (0.8276 μg/cm2 h) was close to that of the pure drug dispersion (0.8482 μg/cm2 h), whereas significantly lower flux of 0.748 and 0.7032 μg/cm2 h was obtained for DSLN1 and DSLN4, respectively. These values indicate the diffusion flow of DTX from its entrapment through the pores of the dialysis membrane expressed as micrograms per centimeter square per hour. The permeation coefficients of the formulations/dispersion ranged between 0.000281 and 0.000339 cm h−1.

Docetaxel solid lipid nanoparticles' release profile.

Flux and permeability coefficient of DTX entrapped in lipid nanoparticles across dialysis membrane.

| Batch | Flux, J (μg/cm2 h) | Permeability coefficient (cm h−1) |

|---|---|---|

| DTX | 0.8482±0.0154 | 0.00033928±0 |

| DSLN1 | 0.748±0.0181 | 0.0002992±0 |

| DSLN3 | 0.8276±0.0227 | 0.00033104±0 |

| DSLN4 | 0.7032± 0.0236 | 0.00028128±0 |

BSLN: blank solid lipid nanoparticle, DTX: docetaxel

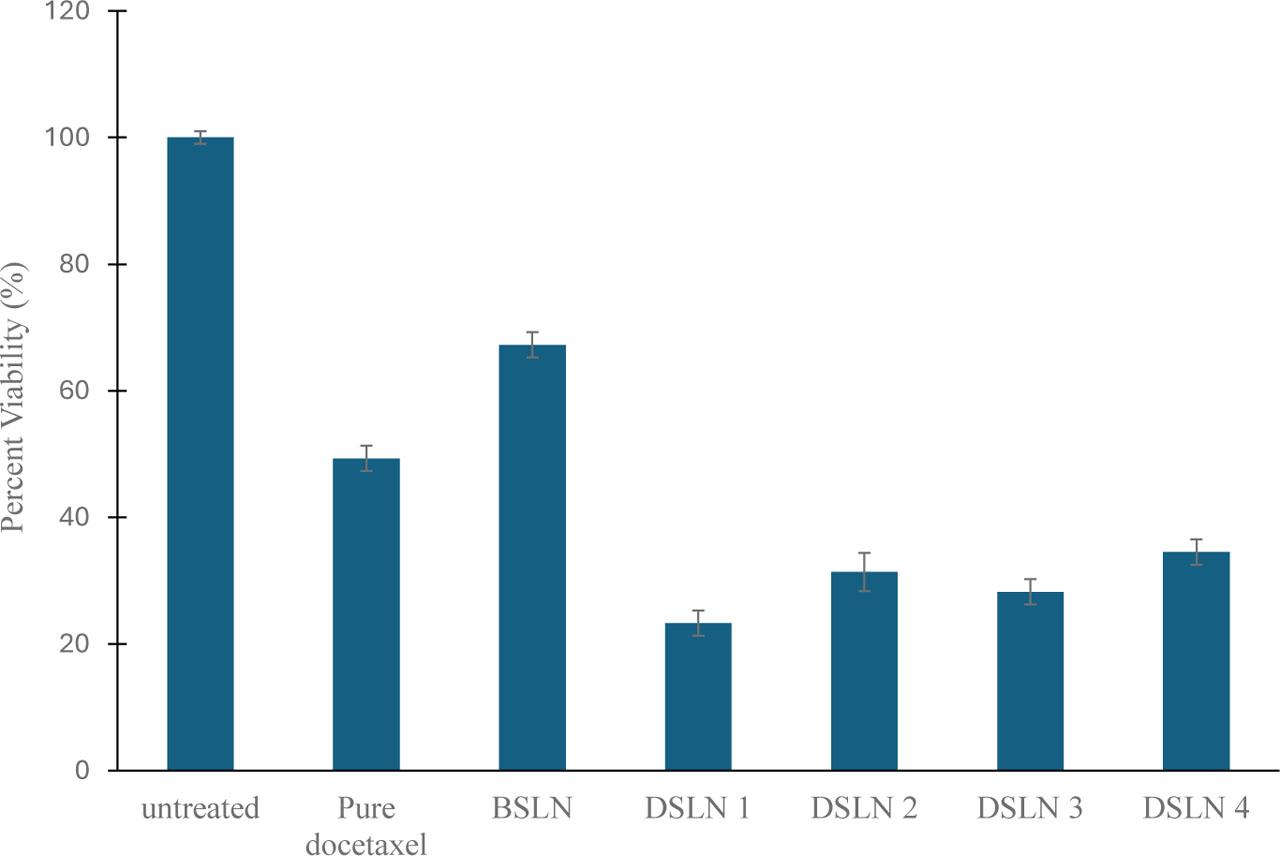

Our study showed that DTX-based SLNs significantly reduced the viability of DU145 PCa cells compared to pure DTX (Fig. 6). The DSLN1, DSLN2, DSLN3, and DSLN4 formulations reduced the viability of the DU145 cells to 23.3%, 31.4%, 28.3%, and 34.5%, respectively. These nanomedicines were more effective than the free DTX (49.3%) (p < 0.05). This shows that lipid matrices can improve the delivery and efficacy of DTX against PCa cells. The inclusion of rubone, which has been reported to be effective in improving the efficacy of DTX against resistant prostate tumor cells (Wen et al., 2017), particularly in vivo, did not significantly interfere with the in vitro functionality of the drug. The results also validate the molecular docking data where cetyl palmitate wax was attributed to have binding affinity for LRP6 which is abundantly expressed in PCa and could serve as a target.

Percent viability of prostate cancer cell line DU145 after treatment with test nanoparticles.

The formulated DTX SLNs were observed to possess a desirable size range for clinically effective nanomedicines, and these formulations were stable with adequate drug loading. In vitro, the DTX nanomedicines significantly reduced the viability of DU145 PCa cells with improved cytotoxicity that is attributed to the choice of lipids and targeting moieties.