Lighthouses represent a complex cultural heritage, both tangible and intangible, of significant historical, technical, architectural and maritime value. The materials used in the construction of the towers, the structural solutions and the apparatus used – reflect technical and industrial progress, the development of maritime trade, shipping and the evolution of ports.

The case study of the Rozewie lighthouses demonstrates how a single set of buildings can be a space that brings together a multifaceted cultural heritage – from its complex and long history and architectural aspects, to its social and professional and symbolic aspects. This analysis provides not only an in-depth understanding of the significance of the lighthouse as a cultural site, but also draws conclusions on the need for an integrated approach to the preservation and popularisation of lighthouse heritage.

The lighthouses on Cape Rozewie form an elaborate lighthouse complex, a complex consisting of two structures located in close proximity to each other. Rozewie I Lighthouse (known as the “old” or “first” lighthouse) is the oldest preserved lighthouse in Poland and is the key element of the complex today. In addition to the active light signal, it also includes numerous auxiliary buildings and is therefore of great interest to visitors. The second structure is Rozewie II lighthouse (“new lighthouse”). It consists of a disused tower, combined with residential buildings and detached outbuildings. In 1910Rozewie II was extinguished, and after a comprehensive restoration of the tower in 2022, it was opened to the public. However, it is worth noting the historical functioning of both beacons simultaneously in ensuring maritime safety.

The aim of this research is to draw attention to the multifaceted value of lighthouses as an element of cultural heritage, containing both tangible and intangible value, and to present the rich history and significance of the selected lighthouse complex.

An analysis of the available scientific studies and literature to date indicates a growing interest in the subject of lighthouses, seen in the context of their historical significance, value as cultural heritage – including technical heritage – and the role of objects as an element of the coastal landscape and as a tourist attraction. Both domestic and foreign literature emphasises their multi-faceted and complex character.

Two main research streams can be found in the literature. The first focuses on the historical and architectural aspects of lighthouses and their role in the development of shipping (Sokołowski, 2006; Hague and Rosemary, 1975; Leba, 1951; Pielesz, 2011). The work by Pietkiewicz, Komorowski and Szulczewski (2020), which presents the development of navigational markings of the Polish coast, the role of lighthouses in the navigation safety system and describes in detail the profession of a lighthouse keeper, occupies an important place in this current.

The second strand of research concerns the contemporary role of lighthouses in tourism and the promotion of cultural heritage, with individual studies devoted to the processes of adapting buildings to new functions, their importance as landscape dominants and carriers of cultural identity (Przyłęcki, 2006; Magnani and Pistocchi, 2017; Moira et al., 2024). This approach is exemplified by the analyses of Chylińska (2019) and Yücel (2023), which point to the potential for tourism development at lighthouses in the context of sustainable heritage use.

It is worthwhile to include studies describing the histories of Polish sites, as well as items focused on specialised issues, touching, for example, on the subject of maritime navigation. On the Polish ground, a special role in popularising the topic is played by the journalistic publications of Łysejko (2008, 2016, 2019), who in his studies shows both the historical dimension and the contemporary transformations of lighthouses – including the lighthouse complex in Rozewie. Pietkiewicz (2011), on the other hand, analyses the limitations associated with the use of lighthouses as tourist facilities, pointing out, among other things, problems with accessibility, funding and infrastructure maintenance. The interest in lighthouses as tourist facilities is also confirmed by conceptual and planning studies, such as the PART SA report (2007), which presents model approaches to the development of cultural routes taking into account coastal infrastructure. Mazur (2010) highlights the cognitive and sightseeing qualities of lighthouses, while Krzysztof J., Parzych K. (2021) analyse their functioning in the context of tourism indicators on the Polish coast. Also foreign authors, such as Šerić et al. (2023), emphasise the need to expand the offer related to lighthouse tourism in order to increase its attractiveness and the variety of attractions offered.

Conservation documentation, including the Historic Monument Record Card for Rozewie II (WUOZ, 2014) provides formal evidence of the recognition of the historical and cultural value of the sites. Source materials from local initiatives and organisations are also a significant source of knowledge, such as an article from the Navigational Marking Database (2020), which reports on the transformations taking place at Rozewie II in recent years.

The research on the complex cultural heritage of lighthouses on the example of sites located in Rozewie was carried out using diverse research methods, integrating both qualitative and quantitative approaches. The choice of methods was dictated by the interdisciplinary nature of the topic, encompassing issues from the borderline of history, architecture, cultural anthropology, sociology and the protection of cultural heritage.

First, an analysis of the literature on the subject was carried out, including scientific studies, historical publications, archival materials and source documents on lighthouses. The aim of this stage was to identify the state of the research, to identify the main thematic threads and to ground the analyses in theory.

In parallel, field research was carried out, which took place in 2022 and included two site visits: a first detailed visit and a second follow-up visit. During the site visit, a detailed observation of the sites and their surroundings was made. The research was exploratory and diagnostic in nature. Extensive photographic documentation was collected as comparative and analytical material, and numerous field notes were taken. On the basis of pre-prepared checklists, data was collected on both the sites themselves (exterior and interior), their functions and uses, as well as the wider spatial and infrastructural context.

The quality of the data obtained through the use of free-form narrative interview methods was also an important methodological element. Interviews were conducted with users, site staff, lighthouse keepers, as well as other people associated with the operation of the sites. The data provided a better understanding of the intangible aspects of heritage and cultural identity attributed to lighthouses, including the Rozewie sites.

A quantitative research methodology was also used to supplement the material with a social component. The questionnaire was designed to identify the level of public awareness of the complex cultural values of the sites.

The use of complex research methods – a combination of literature analysis, field research, interviews and questionnaires – made it possible to capture the multidimensional nature of the cultural heritage of the lighthouses. This made it possible not only to collect historical and architectural data of the sites, but also to understand their contemporary function, significance and role in the cultural landscape of the region.

A variety of methodological tools were used in the research, including a diagnostic survey (using interview and questionnaire questionnaires), document analysis, observation supported by audio-visual devices and survey card sheets, an experiment and a case study.

The case study was based on a comprehensive analysis of a lighthouse complex located in Rozewie – a place with a unique concentration of cultural, historical and symbolic values. The selected case, as the oldest preserved lighthouse object in Poland, is characterised by a rich history, in terms of its material substance as well as its non-material aspects – related to its function, social memory, users’ experiences and the meaning of the place. Rozewie – one of the most recognisable points on the map of the Polish coast, is a unique example of complex cultural heritage. The various phases of development, modernisation and adaptation of buildings over the years have influenced its present and multi-layered character.

Cape Rozewie plays an important navigational role in the southern part of the Baltic Sea. The area, located on a cliff more than 50 m above sea level and at one time considered the northernmost point of the Polish coast [Pietkiewicz, Komorowski, Szulczewski 2020, p. 178], is an area of increased risk for navigation. As early as the Middle Ages, bonfires were lit on its slopes as early forms of traffic lights [5].

The exact date of the construction of the old lighthouse tower on Rozewie is not known [2], however, on the basis of preserved historical maps, it can be concluded that the lighthouse was in operation from the 17th century. There is a hypothesis that the foundations of the present lighthouse may come from the original construction, which is confirmed by an uncovered stone with the engraved date “1731”.

Concepts for a new lighthouse were developed in 1806, one design of which was approved for construction. The construction process was delayed by military action and other difficulties and lasted until the 1820s.The official period of construction was considered to be 1821-1822. It was noted early on in the operation that the trees on the cape were an obstacle to light emission. However, it was decided to leave the trees and send hazard warnings to ships, recommending that a greater distance from the shore be maintained. An additional difficulty in accurately warning vessels at sea was the fact that sequential lights were not possible at that time in history [1].

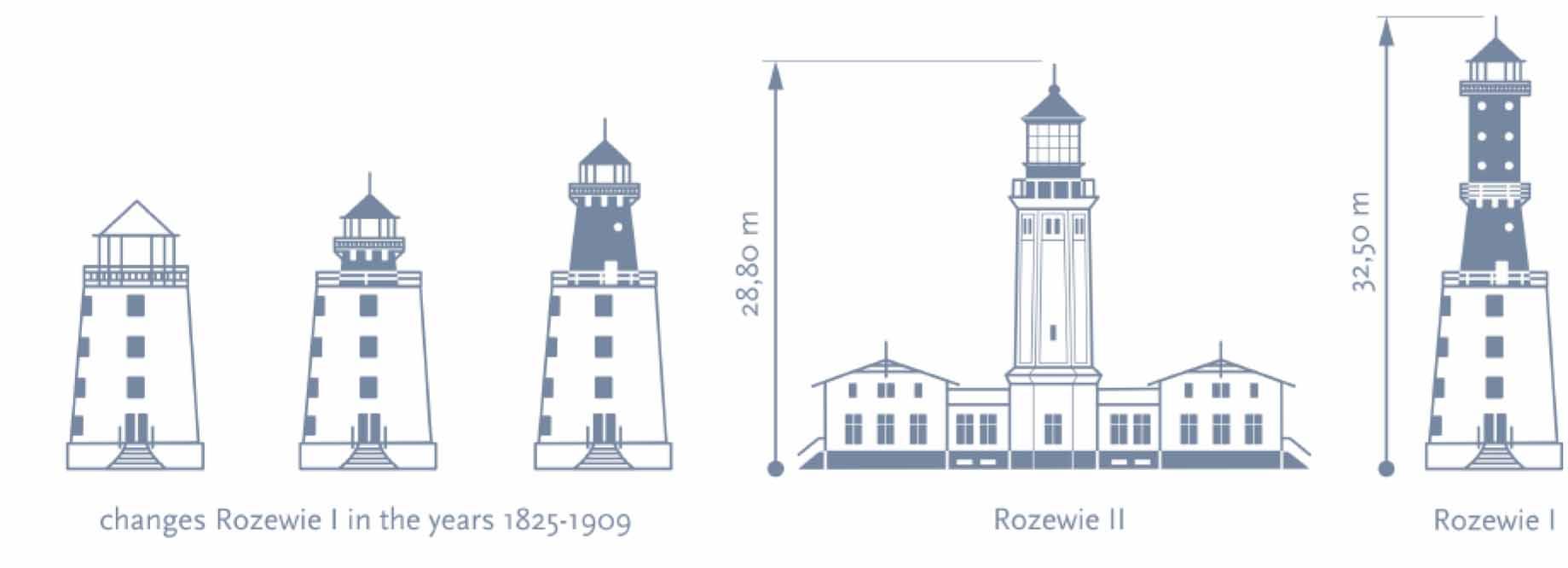

Between 1873 and 1875 a new structure (Rixhört 2) was erected approximately 190 m west of the existing Rozewie I lighthouse, equipped with an identical optical system to the neighbouring tower. The construction of the second navigation point was aimed at eliminating problems with the identification of the light emitted by the existing lighthouse (distinguishing the cape from the nearby lighthouses in Czołpino and Hel) [4]. The two fixed white light points began operation on 1 January 1875 and operated for 35 years. The buildings belonging to the new lighthouse were the residence of the staff operating both towers. In 1904, the introduction of a flashing light system was considered, but this plan did not materialise. Six years later, the decision was taken to shut down the second lighthouse and modernise the old tower. The scope of work included: raising the tower by 5 m, using a truncated cone-shaped steel segment mounted on the existing stone base, installing an electric bulb and extending the complex with an additional engine room [1]. The photographs (Fig. 1, Fig. 2) and illustration (Fig. 3) show the changes in the form of both lighthouses over the years.

Changes to the Rozewie I lighthouse. Source: collection of postcards by Apoloniusz Łysejko, contemporary photo: A. Pluszczewicz-Fornal

Changes to the Rozewie II lighthouse. Source: collection of postcards by Apoloniusz Łysejko, contemporary photo: A. PluszczewiczFornal

Comparison of the forms of Rozewie I and Rozewie II lighthouses. Graphics: A. Pluszczewicz-Fornal

The important strategic importance of the lighthouses is confirmed by the turbulent history, which shows that they were often the target of attacks during armed conflicts. Luckily the Rozewie facilities did not suffer serious damage [2]. Nevertheless, after World War II, renovation work on the Rozewie lighthouse quickly began and included the modernisation of the optical systems and equipment in the engine room. Operation of the lighthouse was resumed on 5 May 1945, but the activities of the staff were hampered by the presence of Soviet troops. Thanks to the intervention of the Polish authorities, the lighthouse was completely handed over to Poland in October of the same year [1].

Based on preserved photographic material and postcards from the 1970s, it can be concluded that the facade of the Rozewie I lighthouse was overgrown with climbing vegetation [2]. As a result of the growth of nearby trees and the associated gradual obscuring of the optics in the north-western sector, it was decided in 1978 to expand the lighthouse and clean the elevation. The lighthouse was raised by 8 m (in one day), while maintaining the uninterrupted operation of the navigation system at night [1]. As part of the work, the roof was dismantled and a new cylindrical structure with a diameter of 3.5 m was installed, along with a modern rotating panel, which is still functional today. The light characteristics of the lighthouse are unchanged since the inter-war period [2]. Figure 3 shows graphically presented changes introduced in the form of Rozewie I lighthouse tower over the years and a comparison of the present form of Rozewie I and Rozewie II lighthouses.

The Rozewie II lighthouse serving as a meteorological observatory and transmission station

underwent a comprehensive renovation in 2014. The modernisation included replacing the electrical installation and refurbishing the tower, allowing it to be opened to the public in May 2022. In February 2023, further refurbishment work began covering Rozewie I lighthouse and the old engine room.

The Rozewie lighthouse complex represents a wealth of architectural forms and is an example of functional architecture with a technical function. The features of the buildings reflect local cultural and constructional conditions, where functional solutions are combined with attention to detail and spatial composition. Despite successive technical modernisations, the buildings have retained their spatial integrity and high aesthetic value, visible both in the layout of the assumptions and in the elaboration of the architectural detail. They thus constitute valuable research material for the history of architecture and the analysis of formal transformations in the construction of the region.

The Rozewie I lighthouse complex includes a freestanding tower and a number of accompanying buildings of a residential and economic character. The dominating element is the lighthouse tower with a compact, cylindrical body of varied construction: the lower part is made of stone and brick, the upper part is made of steel, with an industrial and austere character, topped with a laterna with a triple gallery and a conical roof. The entrance is accentuated by a granite staircase with a decorative balustrade. Noteworthy are the varied window woodwork and architectural details such as fluted lintels, decorative balusters and muntins. The appurtenant buildings, built mainly of brick (partly rendered), have a simple body and 1-2 storeys. They feature stylistic elements such as blends, pilasters, façade paintings and a half-timbered structure. Woodwork details are also characteristic, including wooden doors with panels and windows with muntin bars. Original and stylized historical elements are preserved (e.g. porch, chimney with decoration, niches with coats of arms). The buildings show a varied state of preservation – some of the buildings bear traces of the passage of time (cracks, loss of plaster, biological overgrowth), but renovation works are planned under conservation supervision. The following photos no. depict the Rozewie I lighthouse complex with close-ups of selected details and the upper part of the lighthouse tower, as at 4-8.08.2022.

Rozewie I lighthouse. Photographs: A. Pluszczewicz-Fornal

Rozewie II lighthouse. Photographs: A. Pluszczewicz-Fornal

The complex associated with Rozewie II lighthouse comprises a residential building integrated with a dominant octagonal tower and outbuildings (a wooden barn and a livestock building). The layout of the building is characterised by symmetry, in which the centrally located tower is inscribed in the elongated rectangular plan of the residential building, with two-storey buildings with gabled roofs on both sides, connected to a lower, single-storey part with a multipitched roof. The materials used in the construction of the building were brick, then the façade was rendered and painted a cream colour, with distinctive features such as a pale red plinth and a red trapezoidal sheet roof on the residential section. The tower uses an alternating rhythm of windows – the lower part is fitted with modern plastic windows, while the upper part retains the wooden joinery. The laterna of the tower is made of metal and topped by an onion-shaped roof with a spire. The building has numerous architectural details: decorative cornices, lisens and an elaborate metal gallery supported by consoles. The farm buildings retain a simple, oblong form with gabled roofs. The livestock building is kept consistent with the colours of the lantern, while the barn, is made of wood. The assessed technical condition indicates that the tower is in very good condition, while the livestock building is clearly distinguished by the technical condition of the facade: visible dirt, unrestored woodwork and a different colour of the plinth. Photographs show the Rozewie II lighthouse complex with a close-up view of the upper part of the lighthouse tower, photo taken 4-8.08.2022.

With advances in technology, historically lit fires on cliffsides and simple structures have gradually been replaced by increasingly sophisticated light sources. Over the years, lighthouses have used a variety of fuels such as paraffin, rapeseed oil, coal gas, oil gas, spirit, acetylene, LPG, benzene and propane. With the invention of electricity, lighthouses began to use electricity as their main power source [9]. The introduction of automatic systems has greatly increased the efficiency and range of beacons, providing greater navigational safety, even in severe weather conditions. Today’s beacons are reliable and much more efficient, and modern technology minimises the need for constant staff supervision.

The optics, power source and solution used in Rozewskie lighthouses have also undergone changes from their inception to the present day. Initially, the lighthouse (from 1822) was powered by oil and the optical device consisted of 15 Argand lamps in concave mirrors arranged in a semicircle in two rows, with 6 lamps in the upper row and 7 in the lower row [1]. Then, in September 1866, the type of power supply was changed to refined oil and the light source to a lamp containing a burner with 4 wicks. The optics at the time were a Class I Fresnel lens with a focal length of 920 mm and a diameter of 1.84. This change greatly improved the visibility of the point and increased the range of the light, thus affecting the safety of navigation. In 1875, a second light was commissioned (Rozewie II lighthouse), where a Fresnel I class apparatus was used, the light source was 5 concentric wicks, and paraffin was used for power, the consumption of which was 910 g per hour, yielding 4000 kg per year. In 1878, the Rozewie I lighthouse reported a consumption of rapeseed oil of 45 g per hour, which translated into 2020 kg of oil per year [4]. In 1911, the old optics were replaced by a multi-prism disk lens with a diameter of 1,200 mm, the source was an arc lamp and the power supply was an electric current with a light output of 4,000,000 Haffner candelas. The electric arc was replaced by an incandescent lamp in 1942, with a light output of 1,500 W/80 V in 1945. Currently, as of 2016, the optics of Rozewie I lighthouse are one double-sided panel placed on a rotating table, type PRB-21, with a width and height of 118 cm and a thickness of 29.5 cm. On each side, the panel contains 20 halogen spotlights of 200 W each, arranged 4 each in 5 columns, and is powered by 30 V electric current [2]. The range and characteristics of the light have similarly varied, as has the apparatus, from 5 Prussian miles (35 km) and a steady white light to the current 26 Mm and a flashing white light with FI characteristics, where the lighting time is 0.1 s and the interval 2.9 s, giving a cycle of 3 s. The light is positioned at 83.20m above sea level [1].

Contemporary interior of the lantern of the Rozewie II lighthouse (imitation of an old optical device) and Rozewie I. Photographs: A. Pluszczewicz-Fornal

Lighthouse buildings are an important part of the architectural heritage, many are recognised as legally protected monuments, and their construction reflects a variety of architectural styles and prevailing trends, from classical to modern. Because of their navigational function, the visual characteristics of lighthouses must remain constant and their appearance is precisely defined alongside their light characteristics [10]. The cultural heritage associated with lighthouses also includes equipment, objects, documents and memorabilia related to the operation of lighthouses, maritime traditions and the former life of lighthouse keepers. In the photographs presented below (Fig. 7) you can see former navigation equipment exhibited in the Rozewie I lighthouse tower and in the former engine room of the Rozewie I lighthouse.

Exhibition of old navigation devices in the Rozewie I lighthouse complex. Photographs: A. Pluszczewicz-Fornal

The registration of the Rozewie I and Rozewie II lighthouse complex of buildings in the register of immovable monuments of Pomorskie voivodeship took place on 4 January 1972. Conservation protection covers, apart from the buildings of the lighthouse complex (lighthouse, engine room, signal room, lighthouse keeper's apartment building, lighthouse keepers' apartment building, a former barn, an outbuilding, a smokehouse with a bread oven, the Żeromski monument, the monument to Poland's union with the sea) also the adjacent green areas. In the most recent card of the immovable monument registration No. A-574, entry of 13.11.2014, the condition of the buildings of the complex was assessed as very good and good, no threats and the most urgent conservation postulates were indicated [21]. Since then, however, a number of renovation works have been carried out, maintaining the former architectural character of the complex both outside and inside the buildings, excluding residential interiors. During the restoration of the Rozewie II lighthouse, the idea of installing an external lift [22] was proposed to provide access to the top of the tower for people with limited mobility. However, the idea was put on hold due to the lack of consent from the Conservator of Monuments for fear of excessive interference with the historic fabric of the building.

The profession of lighthouse keeper, strongly associated with the operation of a lighthouse, often went beyond a mere profession to become a lifestyle. Often located in historically isolated and difficult to access areas, lighthouses acted as vital centres for the local community. An important aspect was the concern to maintain generational continuity. Among lighthouse keepers, technical knowledge, maritime skills, values, history, as well as practices and traditions were passed on

from generation to generation. A profession with great responsibility required not only technical expertise, but also adequate physical fitness [1], mental toughness and a willingness to live in isolation [4]. Due to the nature of the work, the lighthouse keeper had to be adequately prepared to function in difficult weather conditions and during night shifts. The problem was highlighted by Talbot as early as 1913: “The character of their duty, under the terrible assaults of the sea, played havoc with the constitutions and nerves of the lighthouse-keepers. They became taciturn, and inevitably fell victims to neurasthenia, owing to their long periods of isolation” [24].

The profession of lighthouse-keeper required a high level of knowledge, commitment and a high sense of responsibility. The responsibilities of a lighthouse keeper were strictly dependent on his rank (senior or junior lighthouse keeper), the historical era, the specifics of the lighthouse operation and its geographical location. In some cases, the candidate lighthouse keeper had to demonstrate previous experience of working at sea. Examples of the tasks of a lighthouse keeper included: maintaining the navigation light from dusk to dawn, maintaining and cleaning the light equipment as well as the lighthouse premises, ensuring that the staff was dressed appropriately, and inspecting the premises, stock and business affairs [11]. Additional duties assigned to the senior lighthouse keeper included, but were not limited to, supervising the duty, controlling the regularity of the watch, managing the stock, taking inventories and maintaining service records. The senior lighthouse keeper was also responsible for reporting on any malfunctions, the timing of planned work, as well as preparing detailed reports and reports on current events and service log entries. In addition, his duties included training junior staff, overseeing the technical condition of signal flags, ropes and masts, as well as maintaining the meteorological logbook. All of the lighthouse keeper's tasks had to be carried out according to strictly established procedures, including rules for observing bodies of water, signalling procedures and how to receive government representatives at the facility. The technical documentation maintained by the lighthouse keeper included detailed technical diagrams of the burners, reflectors and other elements of the lighting equipment that were necessary for the proper functioning of the lighthouse [1].

The literature on lighthouse keeping often emphasises the important role of a strong sense of belonging, identity and pride associated with service. From the moment Poland took over administration of the Rozewie lighthouse after the end of the First World War, one of the most distinguished families of lighthouse keepers, bearing the surname Wzorek, served at the facility. From 1920 to 1939 the managerial post was held by Leon Wzorek, a highly respected figure among the local community. His contributions are commemorated by a plaque placed on the site of the current lighthouse. Leon Wzorek died at the hands of the Nazi perpetrators, who executed him for his activities on behalf of the Polish state. Thereafter, a number of lighthouse keepers served in the service, among whom the Wzorek family continued to hold the post of lighthouse keeper; these were: Władysław Wzorek (1945-1975) brother of Leon Wzorek, Zbigniew Wzorek (1973-1985), son of Władysław [1]. Historical photographs of the Rozewie lighthouse staff are presented below (Fig. 8).

Lighthouse keepers of Rozewie lighthouse. Source: collection of postcards by Apoloniusz Łysejko

Due to the need for lighthouse keepers and their families to be self-sufficient, there was a development of culinary skills, as evidenced by the presence of bakeries and fish smokehouses on some lighthouse sites. Lighthouse keepers were often involved in fishing, hunting, farming and gardening. Many of these facilities were inhabited by entire families of lighthouse keepers. This was also the case with the Rozewie lighthouses. When Rozewie II lighthouse was commissioned, it housed accommodation for 5 lighthouse keepers employed to operate the facility with their families. The illustration below (Fig. 9) shows a floor plan of the Rozewie II lighthouse, where the division of the space into 4 flats is noticeable. As there is no separate fifth flat for the lighthouse keeper, it should be assumed that he lived in an adapted technical space, in the attic of the building, or shared a flat with another member of staff. In accordance with their position in the lighthouse, each family was allocated a flat; in addition, they were given 16 hectares of farmland to grow potatoes. Technical and storage rooms were located in the basement. On the premises of Rozewie I lighthouse there is a bakery-smokehouse building, which once performed important economic functions (Fig. 10). Inside there is an original bread oven with a small hearth and a place to put baked goods in wicker moulds, various formerly used utensils are also exhibited. In the interior, one can notice a wooden staircase leading to the smokehouse located on the mezzanine floor, where fish was smoked using hardwood (mainly beech). Sokolowski points out the many challenges, such as limited access to food supplies, difficulties in obtaining medical assistance and limited educational opportunities for children in many lighthouses [7].

Interior of the Rozewie II lighthouse with an adjacent building. Graphics: A. Pluszczewicz-Fornal

Interior of the bakery with a smokehouse at the Rozewie I lighthouse and the barn and livestock building at the Rozewie II lighthouse. Photo by A. Pluszczewicz-Fornal

Nowadays, the number of lighthouse keepers on duty in Polish lighthouses is relatively small and it is no longer common for permanent staff to reside within these facilities. In view of the ongoing technological changes and increasing requirements for navigational safety, the function of a lighthouse keeper is undergoing a significant transformation. In addition to overseeing the operation of the lighthouse and ensuring the uninterrupted operation of navigation lights, lighthouse keepers often handle tourist traffic. Today's demands necessitate adaptation to advanced technological systems related to both navigation and management of maritime infrastructure. Their duties focus on monitoring and maintaining equipment, as well as ensuring the proper functioning of light, sound and radio systems. Currently, three employees perform lighthouse-keeping duties at the Rozewie I lighthouse: senior lighthouse keeper Aleksander Krężałek, his son Artur Krężałek and Zdzisław Ciechanowski [1].

The activities of lighthouse keepers continue to play an important role in the proper maintenance of lighthouses and, above all, in the preservation of the cultural heritage of coastal areas, as also confirmed by foreign literature. As Moira, Mylonopoulos, Kakaroucha (2024) state in: “Their profession is considered obsolete, or even unnecessary, but their regular presence at lighthouses seems to be a catalyst for the sustainability of buildings, the surrounding environment, land and seascapes” [18]. And also, in an article by MacDonald (2018), he analyses how contemporary lighthouse keepers are carrying out actions to preserve the structures as heritage sites: “Their actions literally stave off the disappearance of the lighthouse. “keeping” should be seen as a fruitful heuristic for recognizing, explaining, and critiquing material work as cultural-historical” [23].

Lighthouses play a key role in the seascape, being important landmarks visible from considerable distances. Due to their height, towers often form clear, contrasting dominant points of the seascape [12]. In a social context, lighthouses are also associated with travel, holiday relaxation, the sea and the beach, being icons of coastal towns, coastal communities and sailing traditions. To quote Chylinska (2015): “Until today lighthouses have been the most durable and solid element of traditional maritime shipping, fishery and tourist landscapes” [15].

Lighthouses have symbolic significance in a variety of cultural fields, from art, literature and music to popular culture. They are attributed with a variety of connotations such as hope, adventure, guidance, signposting, protection and communication, and are a symbol of maritime safety for sailors.

In contemporary research on cultural heritage, increasing attention is being paid to its role in shaping the identity of local communities and in the development of tourism. Understood not only as material traces of the past, but also as an element of the landscape, heritage takes on particular importance in the context of the tourist attractiveness of regions. As Magnani and Pistocchi (2017) note: “Heritage is central in the development of the global tourist system, being able to attract tourists interested in the memory and identity of the population who inhabits those places (…) Landscape is included in the definition of heritage not only for its historical or aesthetical value, but also for its contribution to economic development: landscape is capable of influencing the tourist attractiveness and it may be one of the pillars of the tourist development policy of a region, making of it a tourist destination” [19]. Not surprisingly, lighthouses located in picturesque coastal areas are an important element of the tourist offer, positively influencing economic development at both local and national levels [6]. Often their function is complex, also including educational and museum spaces in addition to a vantage point.

Sometimes tourism also has a negative impact on lighthouses, turning them into highly commercialised objects. Their images are commonly used on various types of seaside souvenirs, in the interior design of restaurants service establishments or hotels. Historic buildings lose their authenticity, becoming places of consumption, the architecture is overshadowed by advertisements and umbrellas, and unsightly snack and souvenir stalls appear in their areas.

In the case of the Rozewie lighthouse, a decision was made in the 1960s to open the old lighthouse to tourists. The result was the establishment of the Lighthouse Museum, which functions as the oldest and largest museum institution of its kind in Poland. The functioning open-air museum has a rich collection of exhibits related to the history of lighthouses. Tourists have the opportunity to visit the interior of the tower with permanent exhibition halls, the barn building, the former smokehouse with a bakery (Fig. 10) and the engine room. The 4 floors of the lighthouse have been adapted for exhibition purposes, where, apart from the history of lighthouses and information on marine navigation and sailing, an exhibition devoted to the Maritime Office in Gdynia, a display of miniature lighthouses of the Polish coast, great geographical discoveries and the history of the lighthouse in Rozewie is presented. On display in the tower is the original rotating panel, which was dismantled during the 1978 renovation. In addition, the complex offers a variety of attractions such as an exhibition of historical navigational equipment, monuments, a reconstruction of an old crane lighthouse and information boards. The former barn building houses an exhibition hall for temporary exhibitions, as well as a ticket office combined with a gift shop. An exhibition of historic navigational machinery and equipment is housed in the former engine house, and the preserved interior of the former bakery and smokehouse contains imitations of fire in the oven and smoked fish, as well as old tools.

The Rozewie II lighthouse was not open to tourists for many years, this changed in May 2022, when only the lighthouse tower was opened to the public, the rest of the complex being inhabited and inaccessible.

In order to encourage tourists to visit the lighthouses, entities managing tourism at the sites undertake various promotional activities, such as creating tourist trails [3], organising cultural events, festivals or selling collectible souvenirs. In Poland, there is the Lighthouse Lover’s Passport initiative, introduced by TPNMM, which allows visitors to earn badges and free admission to the sites after collecting a sufficient number of stamps. Rozewie I Lighthouse is also part of the Lighthouse Route.

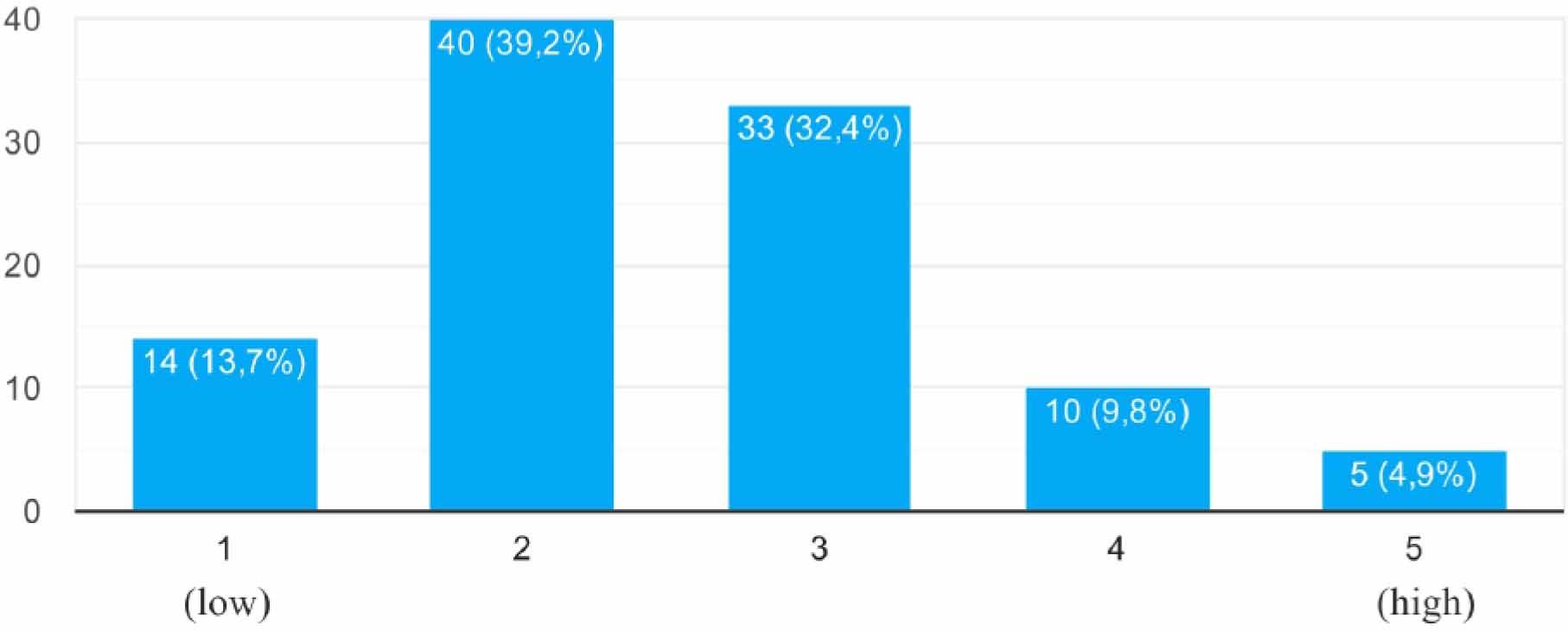

The survey was conducted on a group of 102 respondents, using the online tool Google Forms. The aim of the exercise was to determine users' awareness of the complex cultural heritage value of lighthouses. In a closed question, as many as 61.8% of respondents (63 people) had heard of lighthouses in the context of cultural heritage, and the vast majority of respondents rate their value highly: 31.4% (32 persons) rate the value of lighthouses as cultural heritage objects as 5 (on a five-point scale), 25.5% of the respondents (26 persons) as 4, the largest group (33 persons, 32.4%) rated the value as 3.

The result of the collected answers to the question “Have you heard of lighthouses as cultural heritage objects?” is presented below. (Fig. 11):

Presentation of selected survey results. Prepared by: A. Pluszczewicz-Fornal, graphics generated by Google Form

Diagram showing the collected responses to question 9: “In your opinion, has the significance of the lighthouse changed over the years?” (Fig. 12):

Presentation of selected results of the survey. Prepared by A. Pluszczewicz-Fornal, graphic generated by Google Form

Respondents were asked to identify related aspects of cultural heritage to lighthouses, the question offered multiple choices. Among the responses, the element of the seascape was indicated by most people (90 people, 88.2%), followed by architectural heritage (82 people, 80.4%), historical significance (72 people, 70.6%). Technical heritage and tourism product were indicated by 52 people (51%), while 49% (50) of respondents indicated the specificity of the lighthouse keeper's work. The remaining questions received less than 50% of responses and included: other material heritage (34.3%), symbolism and meaning (45.1%), traditions and customs (43.1%), social aspects (14.1%), and consumer product (3.9%).

The responses of 102 respondents to question 6, which reads: “How do you assess the importance of lighthouses as cultural heritage sites?” (Figure 13):

Presentation of selected results of the survey. Prepared by A. Pluszczewicz-Fornal, graphic generated by Google Form

The collected responses to question 8: “What aspects of cultural heritage do you think are associated with lighthouses? (more than one answer can be marked)” (Figure 14).

Presentation of selected results of the survey. Prepared by A. Pluszczewicz-Fornal, graphic generated by Google Form

According to the vast majority of those questioned, the importance of the lighthouse has changed over the years, with 27.5% (28) votes indicating a definite change and 31.4% (32) “rather yes” responses. The responses collected in questions 10 and 11 illustrate the change in importance of lighthouses in relation to the present and historical times, with almost all survey participants indicating a very high importance of the facilities in former times. When asked about the need for legal protection of lighthouses, 87.3% of respondents said that legal protection is needed (56.9% definitely yes, 30.4% rather yes). Only 2 people answered “definitely not” and “rather not”.

Presentation of the collected answers to question 10 with the content: “In your opinion, what is the current importance of lighthouses?” (Fig. 15) and “In your opinion, what was the importance of lighthouses in the past?” (Fig. 16).

Presentation of selected results of the survey. Prepared by A. Pluszczewicz-Fornal, graphic generated by Google Form

Presentation of selected results of the survey. Prepared by A. Pluszczewicz-Fornal, graphic generated by Google Form

Interesting statements were collected in an additional open-ended question, where respondents further emphasised the value of activities aimed at increasing broad public awareness and sensitisation about lighthouses. They also draw attention to their large scale and, at the same time, their invisibility: “however, we often do not notice them at all, nor are we aware of the important role they have played, and continue to play”. Another comment also underlines the lack of awareness of the value of lighthouses and indicates that they are visited “out of boredom” and “inpassing” without any reflection or insight into their significance and history. The respondent additionally emphasises his curiosity about the subject and argues that, in his opinion, the introduction of interesting functions to functioning facilities could increase their visitation.

The collected answers to question No. 12: “Do you think that maritime latrines should be protected by law (register, heritage records)?” is presented in the graphic below (Fig. 17).

Presentation of selected results of the survey. Prepared by A. Pluszczewicz-Fornal, graphic generated by Google Form

The research carried out provided information on the past and the evolution of the navigation infrastructure at Cape Rozewie, taking into account contemporary transformations related to the preservation of the material cultural heritage. Other researchers have dealt mainly with general aspects of the history of lighthouses in Poland, focusing on their basic navigational functions and historical facts. The results presented here broadened this picture by providing detailed data on the ongoing modernisations of Rozewie lighthouses and by introducing a social context, concerning the functioning of lighthouse keepers, the lives of families, or the imp act on local communities. Modern automation has had a huge impact on the technical changes in the facilities and the associated transformation of the nature of lighthouse keepers' work, which is now a disappearing profession. In addition, the remaining non-material values of lighthouses, which include symbolism, are presented.

Conclusions from the author’s research indicate the necessity of modernising, adapting and conserving the facilities while preserving the tangible and intangible cultural heritage of lighthouses and increasing public awareness of them.

Further activities are planned to determine the adaptation possibilities of lighthouses on the Polish coast, in-depth architectural, structural and functional analyses of the objects and citing examples of foreign objects.

The presented results allow for a comprehensive look at the monuments, taking into account all aspects of their value, and their publication will help to better understand the role of lighthouses in the context of technical heritage protection.

The lighthouses at Cape Rozewie, thanks to their unique and rich history, are a unique example of this type of building on the Polish coast. The buildings constitute a complex cultural heritage of very high material and immaterial value, including aspects related to the activities of lighthouse keepers and the traditions accompanying their profession. In the case of the Rozewie lighthouse complex, conservation protection covers not only the lighthouses themselves, but also the associated facilities and surroundings. The appearance of Rozewie I lighthouse, due to its navigational functions, must remain unchanged. The renovation work carried out on the facilities focuses on preserving and protecting the original historical features of the lighthouse. When considering the preservation and adaptation of lighthouses, special importance is attributed to their relationship with the surrounding landscape and historical value. As Yücel (2023) points out, an approach that takes into account both the functionality of these facilities and their role as cultural heritage elements is important: “(…) lighthouse, it is in integrity with the rich natural and cultural assets. It is important to protect this integrity. Although it is positive that lighthouses are open to the public with their unique geography, uses that prioritize the recognition of lighthouses as cultural heritage should be envisaged” [20].

The development of technology has had an impact not only on increasing maritime safety for vessels, but also on the architectural form of lighthouses and associated buildings, the profession of lighthouse keeper, the lifestyle and prevailing customs of lighthouse keepers. The upgrades made to the facilities have adapted them to changing environmental conditions and reflect advances in maritime navigation and technology.

Surveys identified the level of awareness of the cultural value of lighthouses. The survey showed a lack of full awareness of the complex and valuable value of lighthouses among respondents, which was also confirmed by the selected answers to the open questions. In terms of links to cultural heritage, lighthouses were most often perceived as an element of the seascape and architectural heritage. Changes in the significance of lighthouses over the years were noted by the majority of respondents, and the need for their legal protection was supported by the vast majority of respondents. The findings suggest that taking steps to popularise lighthouses can strengthen their position in the public consciousness.

In view of the contemporary challenges of their maintenance and management, further interdisciplinary research and activities integrating aspects of heritage protection, spatial planning and local community development are needed.