Urinary incontinence is an important medical and social problem(1) with an overall prevalence of approximately 10–15%(2). Regular pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) is one of the non-invasive methods for treating stress urinary incontinence (SUI)(3). However, beneficial effects of SUI treatment may not be achieved despite properly performed PFMT. Avulsion, i.e. complete tearing of the puborectalis muscle (levator ani muscle, LAM), which compromises pelvic floor muscle contractions in terms of hiatal size(4,5,6,7), is one of the reasons for PFMT failure(4,5,6,7). The relationship between avulsion and SUI has not been clearly determined. Methods used to assess pelvic floor function as well as the complexity of the structure and function of the urogenital diaphragm, including various elements of the nervous system, may be the reason for the controversial results of studies on avulsion(6,7). Visual inspection, palpation, electromyography, prageometry, magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasonography (USG) of the pelvic floor can be used to assess pelvic floor function. None of the methods developed so far comprehensively assesses urogenital diaphragm function in terms of, among others, muscle activation, achieved pressures, the duration of contraction, speed of muscle activation or achieved tissue shifts, if used alone(6). Modified Oxford scale (MOS)(8), which involves pelvic floor muscle (PFM) palpation, is often used to rate PFM contraction (PFMC), both in everyday clinical practice and in scientific research. The method is easy to learn, has good repeatability and does not require specialist equipment.

Pelvic floor ultrasound is increasingly used in the diagnosis of urogynecological patients. It allows for imaging and mobility assessment of many urethral segments(9,10,11). Urethral mobility can be assessed transperineally (TPUS), using a transabdominal probe (pelvic floor ultrasound with transabdominal probe, PFU-TA), and transvestibularly, using a transvaginal probe (pelvic floor sonography with transvaginal probe, PFS-TV). PFU-TA allows for determining urogenital hiatus size at rest, on PFMC and during the Valsalva maneuver, as well as for diagnosing LAM avulsion(12).

Ultrasound does not allow for direct assessment of PFMC strength, which is possible in a clinical examination using MOS. However, digital palpation will not determine the effect of urogenital diaphragm contraction. A more detailed understanding of the relationship between palpation and PFU-TA and PFS-TV could contribute to the development of optimal PFMT qualification methods and improvement of treatment outcomes by using readily available tests that can be repeated multiple times in a dynamic manner.

The aim of the study was to assess the relationship between pelvic floor muscle contraction and urethral mobility and hiatal size, as well as to compare PFU-TA vs PFS-TV in assessing urethral mobility.

A prospective study was conducted among urogynecological patients reporting to the clinic between 2019 and 2022. Patients underwent standardized gynecological and urogynecological history collection, gynecological and urogynecological examination, including Pelvic-Organ-Prolapse-Qualification (POP-Q)(13), MOS, and ultrasound(14). Patients with a history of urogynecological procedures, pelvic radiotherapy, significant pelvic organ prolapse (POP-Q >2 in at least one compartment) and uni- or bilateral LAM avulsion were excluded from the analysis. MOS, which is characterized by good repeatability and reproducibility, was used for clinical evaluation of PFMC(15). An experienced specialist rated PFMC on a six-point scale from 0 to 5 (Tab. 1)(16,17).

Oxford Scale(8)

| Grade | Pelvic floor contraction |

|---|---|

| 0 | No contraction |

| 1 | Minor muscle ‘flicker’ |

| 2 | Minor muscle contraction |

| 3 | Moderate muscle contraction |

| 4 | Good muscle contraction |

| 5 | Strong muscle contraction |

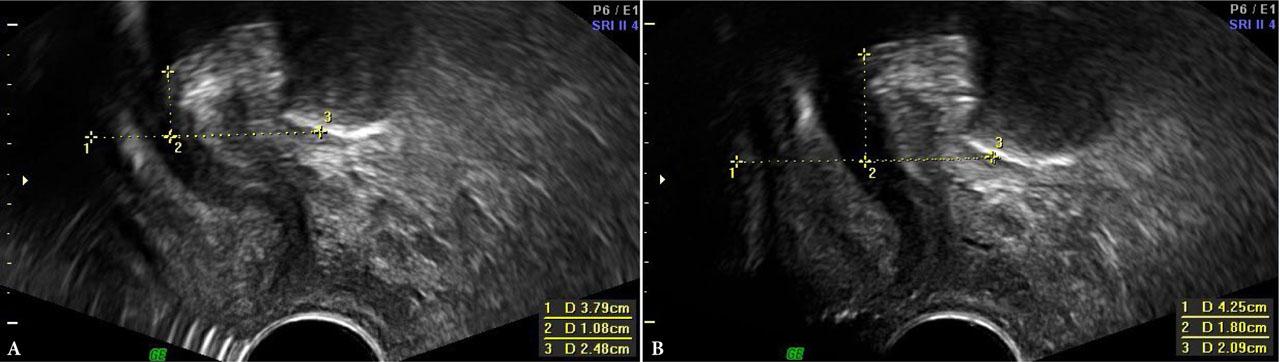

PFU-TA and PFS-TV were performed by another specialist with extensive experience in both techniques, who was blinded to MOS findings. Ultrasound was performed on the GE Voluson 730 PRO and GE Voluson 730 EXPERT systems, using the GE RAB4-8L Convex 4–8 MHz transabdominal probe and the GE RIC5-9E 5–9 MHz transvaginal probe. LAM assessment and urogenital hiatus measurements were performed on an empty bladder, at rest and on maximum PFMC, using 4D imaging, following a technique described by Dietz (PFU-TA)(18,19). The analysis included differences in hiatal area, circumference, transverse and longitudinal dimensions (A, C, T, L, respectively), measured at rest and during PFMC. The values of ΔH, ΔD and vector = √ (ΔH2 + ΔD2), obtained in PFU-TA and PFS-TV imaging, were used to assess the ultrasound parameters of urethral mobility(20,21) (Fig. 1).

PFS-TV – measurement of urethral mobility parameters at rest and on PFMC. A. At rest. B. On PFMC. 1 – horizontal axis; 2 –H; 3 –D

Pearson’s linear correlation coefficient was used to demonstrate the relationship between the parameters obtained in PFU-TA and PFSTV, and the contraction force rated with MOS. Bland-Altman analysis was used to assess the agreement between PFU-TA and PFS-TV. All analyses were performed using an Excel spreadsheet. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Medical University of Lodz.

The study included 272 patients with a mean age of 59 years (29–81 years), BMI of 26.72 kg/m2 (17.58–39 years), and a mean number of childbirths of 2. No history of forceps or vacuum delivery was reported. Stress urinary incontinence and overactive bladder were reported by 23.5% and 8.8% of patients, respectively. The mean MOS value was 2. There were 120 patients (44.11%) in MOS 0–1 subgroup, 132 patients (48.52%) in MOS 2–3 subgroup, and 20 patients (7.35%) in MOS 4–5 subgroup. The groups did not differ significantly in terms of age.

Pearson correlation coefficients between PFMC MOS and urethral mobility parameters and the urogenital hiatus size are presented in Tab. 2.

Pearson correlation coefficients between muscle contraction by Modified Oxford Scale and urethral mobility parameters and urogenital hiatus size

| Parameter | Pearson correlation coefficients (r) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| ΔH TV | 0.45 | <0.00001 |

| ΔD TV | −0.55 | <0.00001 |

| Wektor TV | 0.54 | <0.00001 |

| ΔH TA | 0.34 | <0.00001 |

| ΔD TA | −0.33 | <0.00001 |

| Wektor TA | 0.36 | <0.00001 |

| A | 0.06 | 0.325 |

| C | 0.09 | 0.140 |

| L | 0.12 | 0.051 |

| T | 0.08 | 0.190 |

A – hiatus area; C – hiatus circumference; L – longitudinal h. size; T – transverse h. size; TA – transabdominal; TV – transvaginal

A statistically significant positive correlation was demonstrated between PFMC and ΔH and vector parameters for PFS-TV (r = 0.45 and r = 0.54) and PFU-TA (r = 0.35 and r = 0.36). The ΔD parameter correlated negatively with MOS (r = −0.55 in PFS-TV, r = −0.33 in PFU-TA). However, no correlation was demonstrated between MOS and the analyzed urogenital hiatus parameters: A, C, L and T.

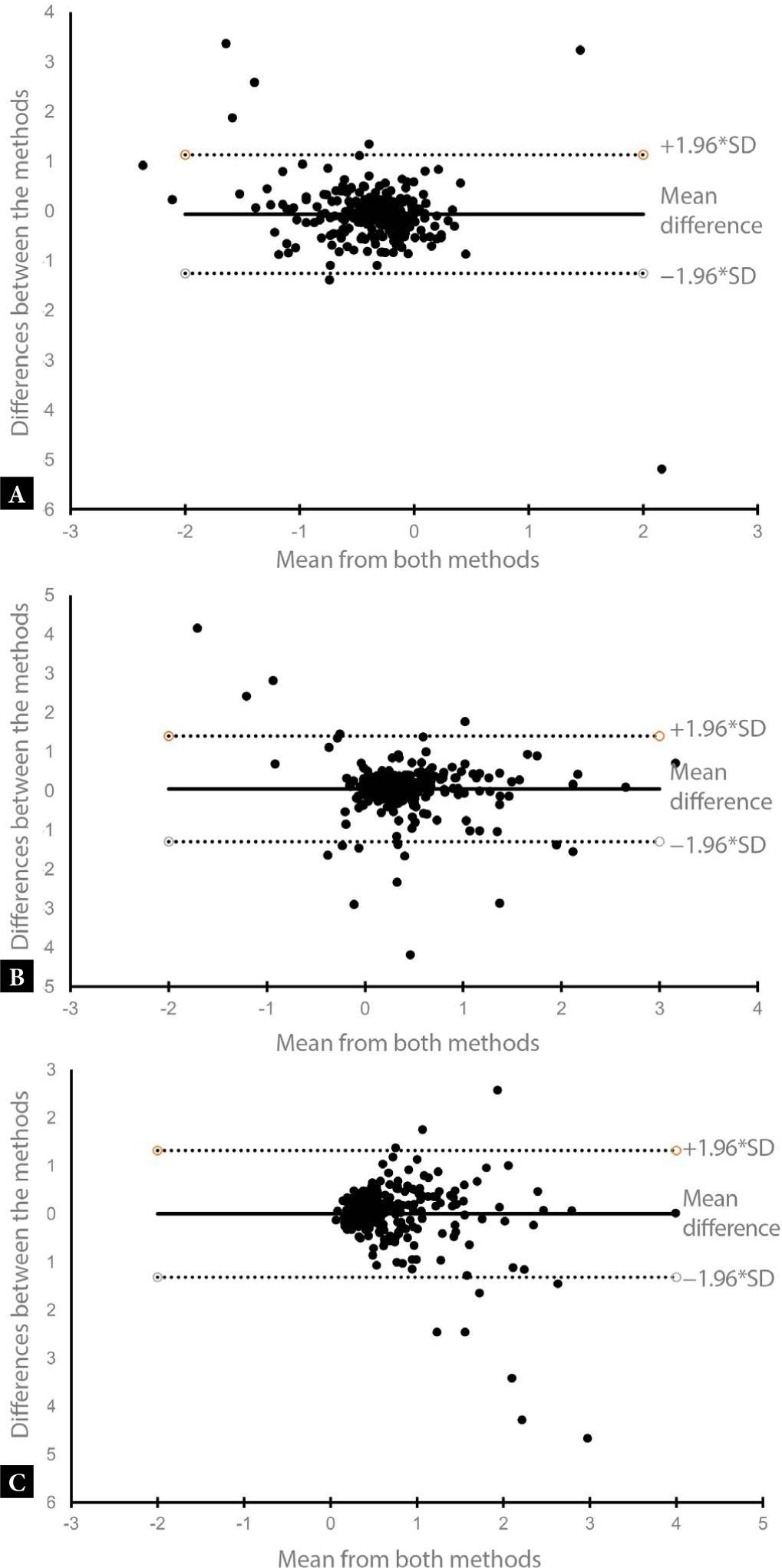

Bland-Altman analysis showed good agreement between PFS-TV and PFU-TA for ΔD and vector parameters, with Bland-Altman coefficient of 2.9% and 3.7%, respectively, while this coefficient was 5.9% for ΔH (coefficient <5% indicates good agreement between the two methods) (Fig. 2). It should be noted that there was a statistically significant correlation between PFS-TV and PFU-TA for the ΔH parameter (p <0.00001).

Bland-Altman plot for parameters ΔH, ΔD and vector – PFS TV vs. PFU-TA: A. ΔH. B. ΔD. C. Vector

The mechanism underlying urinary continence in women is the result of not fully understood interactions between different anatomical structures(22,23). PFMC plays an important role in the noninvasive treatment of SUI. Meta-analyses of studies using PFU-TA present diverse findings: from a significant to weak correlation between PFMC and urinary continence(24,25,26,27,28). The discrepancies may be caused by, among others, differences in the percentage of patients with and without LAM avulsion and differences in the distribution of POP grades (29,30). The results on the effect of LAM avulsion are controversial. LAM plays an important role in supporting various urogenital diaphragm structures. LAM damage may have a negative effect on the strength of pelvic floor muscle contraction. However, the impact of LAM avulsion on various functions, including urethral mobility as well as urinary and fecal continence, is not fully understood. The research to date is ambiguous, with some studies indicating no effect of avulsion on the symptoms of SUI and fecal incontinence, and other suggesting an increased risk of these symptoms in avulsed patients(6,7). In our study, we assessed pelvic floor muscle function in patients without avulsion. Analyses of PFU-TA results in the general urogynecological population included the impact of PFMC on only two parameters (urethral mobility vector and the long axis of the urogenital hiatus) and showed different findings(7). Therefore, we comprehensively analyzed the effect of PFMC on urethral mobility and urogenital hiatal size using multiple ultrasound parameters, excluding patients with avulsion and clinically significant POP. PFU-TA has not been compared with PFS-TV so far. Knowledge about the differences and similarities of both methods would allow for optimal determination of their usefulness in both clinical practice and scientific research.

Our study demonstrated a correlation between MOS contraction force and urethral mobility parameters assessed in PFS-TV and PFU-TA. The correlation coefficient was higher for PFS-TV. Bland-Altman analysis showed good agreement between the two methods of measuring urethral mobility, mainly for the ΔD and vector parameters. The strongest correlation was found for ΔD. Previous studies assessing urethral mobility in PFS-TV were most likely to utilize ΔH, defined as bladder neck descent (BND). Our study suggests that an additional use of ΔD and vector parameters can determine urethral mobility more precisely; therefore, future studies should consider using all three parameters, which will allow for a more comprehensive assessment of the effect of PFMC on urethral mobility. The differences in urethral mobility results that may occur between PFU-TA and PFS-TV require further research. Different US findings may result from, for example, the size of US probe, its surface of contact with the perineum, or the probe’s pressure on the investigated area.

The analysis showed no impact of the resting size of the urogenital hiatus on PFMC. This indicates the involvement of additional factors, other than stretching of the urogenital hiatus, that have an impact on PFM contraction efficiency. We have not confirmed the influence of MOS contraction force on the hiatal size in PFU-TA; therefore, it seems that pelvic floor palpation and US assess different aspects of muscle function this region.

The lack of precise diagnosis of SUI and fecal incontinence, and the lack of analyses of the influence of the verified parameters (MOS, US) on the symptoms of incontinence are limitations of our study. However, the analysis had a different focus. A positive aspect of the study is the fact that the ultrasound scans were performed by one specialist, with extensive experience in both methods used, which is not common. Our analysis confirmed that reinforcing PFMC alone may not be sufficient to achieve a positive effect in the treatment of urogynecological conditions.

MOS-rated PFMC correlates with urethral mobility in PFS-TV and PFU-TA imaging. The most comprehensive analysis of urethral mobility is achieved using three analyzed parameters (ΔH, ΔD, vector). There are slight differences in the analyzed urethral mobility parameters between PFS-TV and PFU-TA. The influence of MOS-rated PFMC on the size of the urogenital hiatus was not confirmed.